Steve Audette, ACE has been editing at WGBH since 1990, mostly as the Senior Editor on two of PBS’s flagship products, NOVA and Frontline. His latest documentary just won a host of national awards and Steve is well known for his generosity in sharing his editing knowledge.

Steve Audette, ACE has been editing at WGBH since 1990, mostly as the Senior Editor on two of PBS’s flagship products, NOVA and Frontline. Steve and I met when we were both selected to take part in the first Avid Master Editors Retreat in 1996 in Martha’s Vineyard. I’ve followed Steve’s critical successes as an editor since then and figured that this would be a great time to catch up with him. One of his last documentaries “United States of Secrets” recently won EMMYs for Best Documentary and Best Current Events Long Form, as well as a Peabody Award and a duPont Columbia Award for journalism. In this conversation we talk about “United States of Secrets” and another of his big double-episode Frontlines from 2013, “League of Denial” which is about the NFL concussion cover-up and the discoveries of Bennett Omalu, M.D. (the same story covered in Will Smith’s “Concussion” feature film). League of Denial rebroadcasts December 15 (part 1) and December 22, 2015 (part 2). It also garnered a host of awards, including a Peabody Award and a George Polk Award.

You can watch both films in their entirety using these links for “United States of Secrets” and “League of Denial.”

HULLFISH: This process of producing, writing, shooting and editing a Frontline is so fascinating that I want to cover a lot of the pre-production and production stuff in a separate article, so let’s focus today on just the editing. Where does that start?

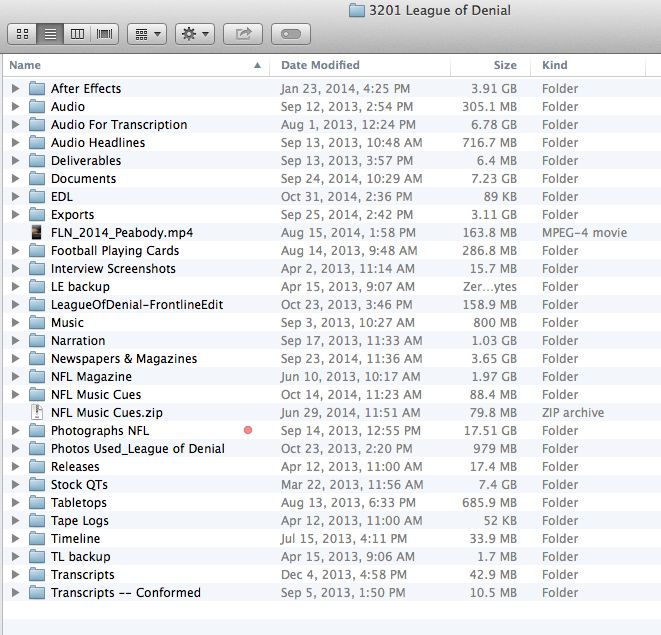

AUDETTE: This is a big question. I will have to truncate some of the process, but it starts like this.While the interviews are getting shot an associate producer and production assistant are looking for documents, footage, and photographs that might pertain to the story. They’re building a giant file database on a RAID that is divided up per project into photographs, documents and video clips. Generally we look at that through Adobe Bridge for photographs and documents and the clips are automatically imported into the Media Composer at a later date when the edit room opens.

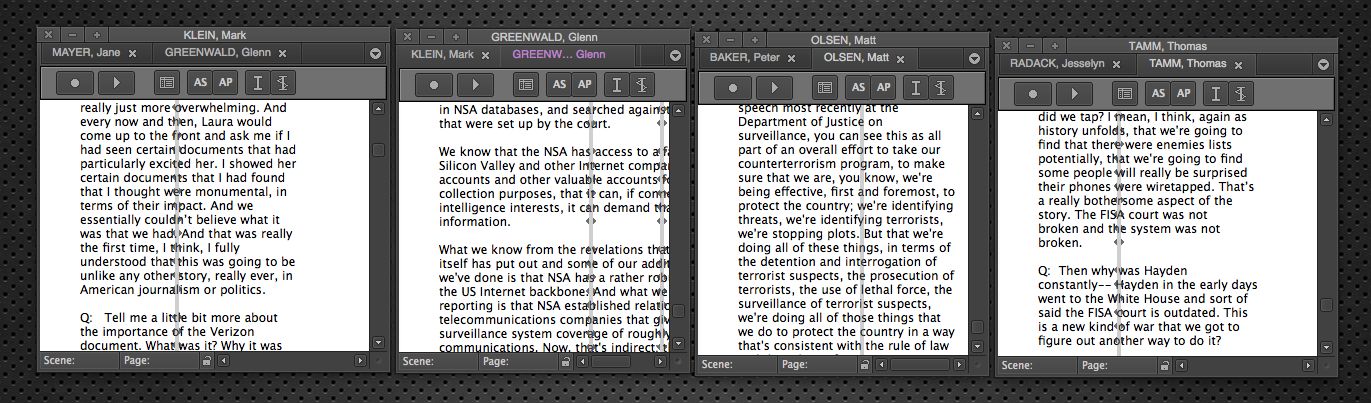

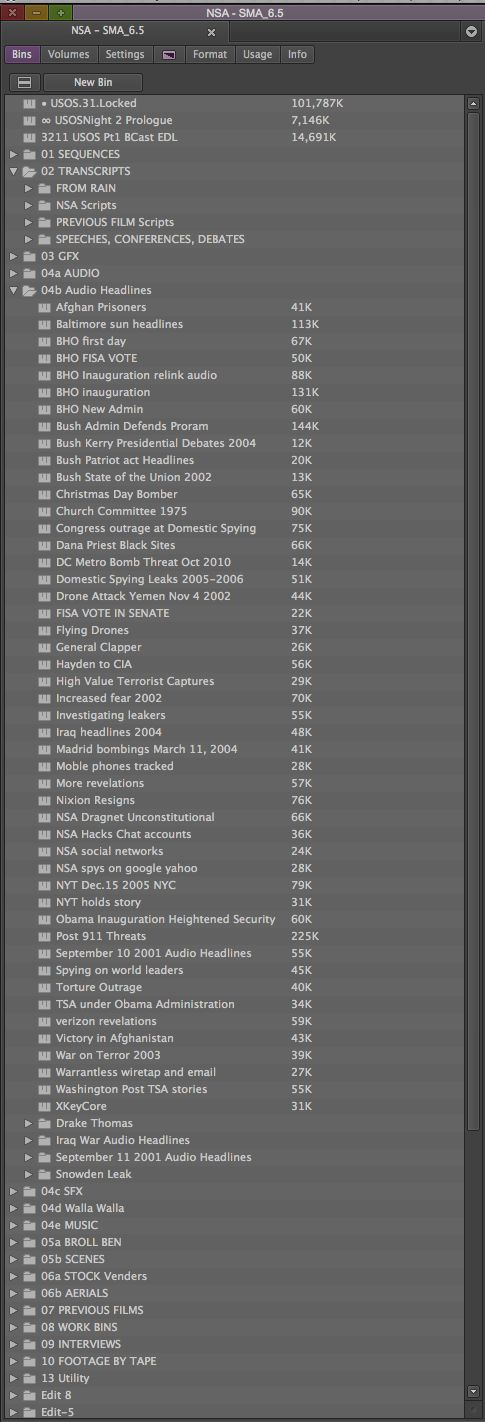

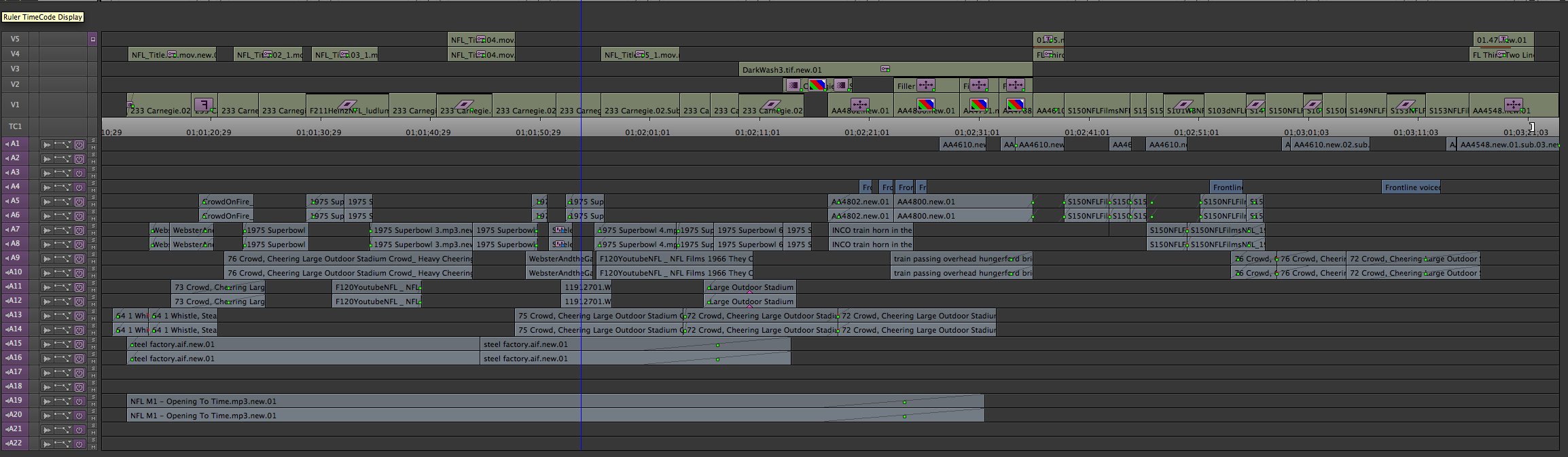

When I come in on the first day, my assistant editor, Elliot Choi has transcoded all of the media. He links to the media via AMA and then transcodes to the Avid ISIS in Standard Definition. The primary media is transcoded to 2:1s and the copious stock footage is brought in at 4:1s.Our shooting ratio is something like 200:1. Every interview, important speech, or event that is part of the narrative is transcribed and the media is ScriptSynced. Most of the documentary content is edited from those ScriptSynced bins. Not footage bins.

Most of this work is done by Elliot, my assistant editor, and he is absolutely fantastic. He breaks the project down into interviews, stock footage, audio, graphics and some utility folders. Every project starts out looking the same.

HULLFISH: These are folders, not bins, right? Then there’s further breakdown into bins inside those folder?

AUDETTE: Right. Inside the folder for interviews, there’s a folder for every interview.

Non-interview Footage for scenes is segregated to bins. For example all shots of the White House are sub-clipped into one bin.

Audio headlines of news reports are gathered into bins for important moments in the narrative based on the subject. Later I will use these to make an audio fugue of headlines speaking out like a Greek chorus.

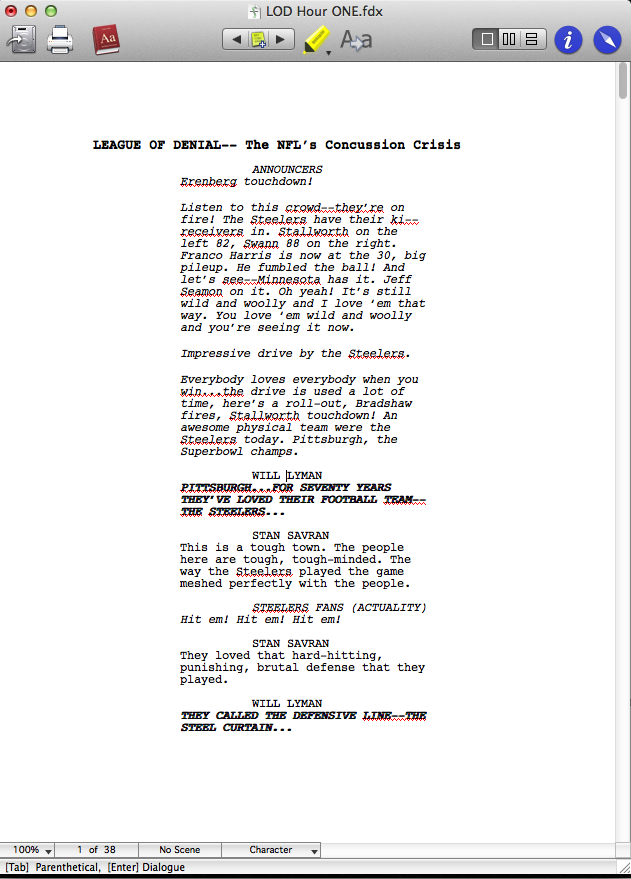

The director and I come in on the first day and he’ll say, “Here are the first five pages of the script.” Which he sends electronically to me. (A two hour show, final script is about 82 pages.) As we cut, the script is written very much in the fashion of Hollywood theatrical script.

HULLFISH: Most docs would use a two column video format. Why use a dramatic scripted format?

AUDETTE: At FRONTLINE, we think of our docs as films, so we usually write in that format. Kirk’s team uses FinalDraft.

After he sends me the copy for the day, I start building a sequence. It includes narration, because at Frontline, we are big believers that narration is your friend. However it’s very easy to over-write when using narration, so we kind of do haiku narration. What we are looking for from our narration is to deliver a context or a connection for the audience and get out of the way so the story can unfold. We write it in the voice of our narrator, Will Lyman, who is one of those amazing “Voice of God” guys with great delivery.

We’ll record scratch right there and start cutting sync bites and narration. We do that really quickly, just to get a sense of “Does any of this really work?” because when you’re reading sound-bites in a document, you might think that bite sounds great, but you really have to listen to it and watch them say it, to get a real sense of how good that sound-bite is. Also, interviews are shot with two cameras. A C300 on a tight shot, almost full head down to the shoulders. Then right next to the C300 is a 5D Mark III that is wide.

HULLFISH: That’s exactly how I do it.

CutWideForHands from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

AUDETTE: It’s really great, so you can go from a wide to a tight shot. That wide shot is really pretty wide. It’s handy when someone uses their hands to talk. You can cut to the wide to let people have that expression. Cutting between these two shots also helps to make people more clear because you can truncate them down and jump to the second camera for a minute just to get the right sound-bite.

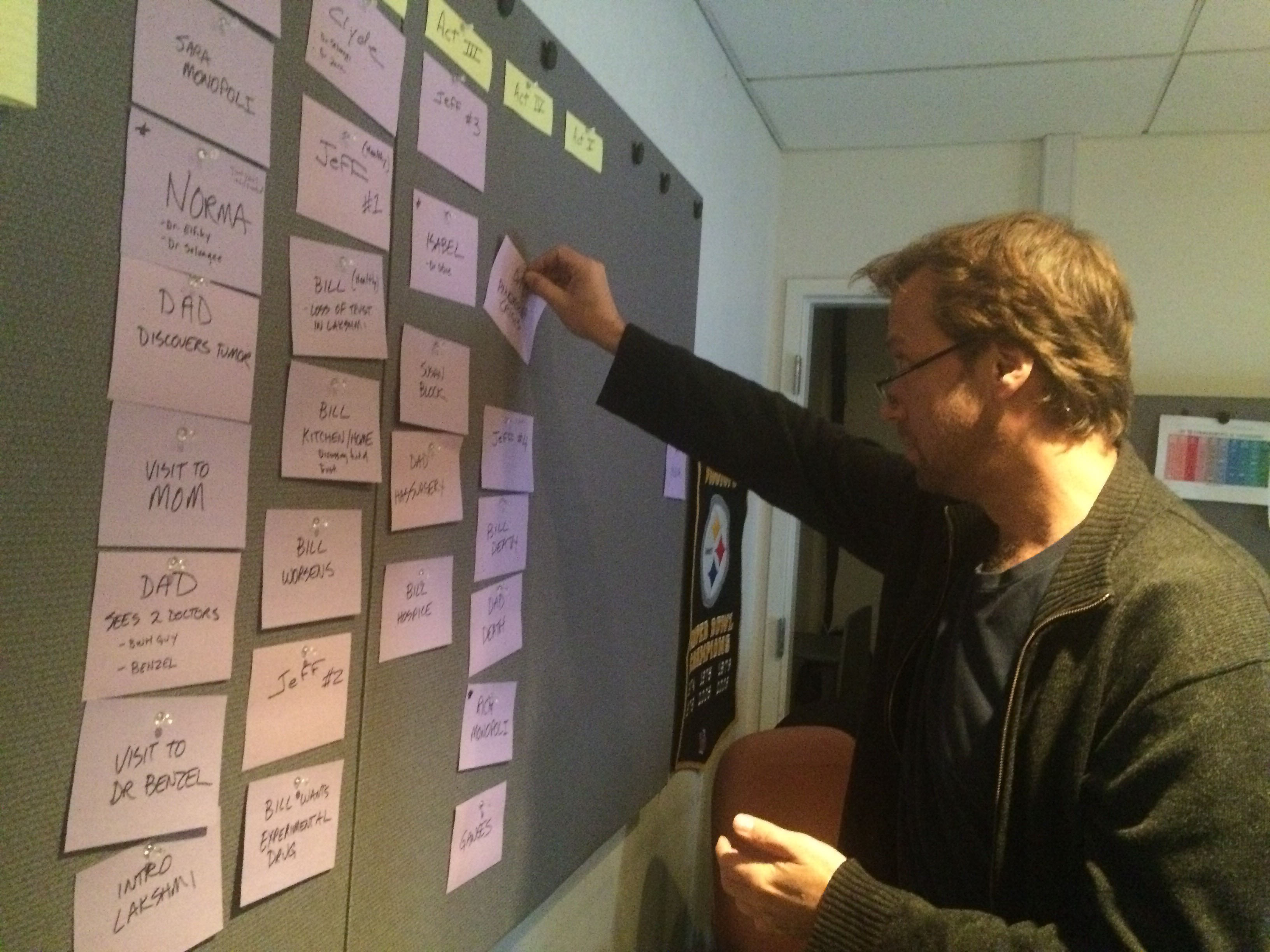

So we quickly assemble that little five page script and we look at it… figure out when it’s boring, and trim it down a little bit, and the very next thing we do is say, “What’s this going to look like? How does it start?” So in “League of Denial,” we know we’re starting in Pittsburgh.

LODOpen01 from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

We know that we’re starting with the Ben Webster story, because he was the first person identified with CTE. How can we bring people to Pittsburgh? We think that’s an important thing. As soon as you possibly can, help people know exactly where you are, what time it is and what kind of place it is. Michael Kirk came up with the idea that football is an active sport of physical labor. Pittsburgh is a steel town. So he said, “What if we cut a scene of steel workers in a factory and talk about it in terms of a battle, like a football game?” So we created that juxtaposition of imagery between the steel mill with the audio from the commentators talking about players on the field and the great Pittsburgh teams.That juxtaposition of two things is something I do a lot. I call it cutting “ambiguity versus clarity.” It’s very clear that you’re looking at steel-working footage but you’re hearing this audio of a football game and that creates a dichotomy of interest. It pulls the viewer in to the story and in to the narrative. They discover their own connection and all of a sudden you have an engaged audience, which I think is the whole point of Frontline.

HULLFISH: You’ve got another of those juxtapositions with some football audio and a plane landing to tell the story of the players’ brains being delivered to Boston.

LODOpen02 from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

AUDETTE: Absolutely. That was the beginning of the second hour of “League of Denial.” It’s about how a brain gets to these doctors. What’s the process? It was kind of a “how to”. The plane lands, it goes through the system, out to a truck to Bedford, Massachusetts where Ann McKee is. So we said we’d do the same thing. We’ll grab the audio from a football game, but we’ll bring it into the world of a plane landing: touchdown! It was a little more complex than the first example, but if you’ve seen the first example it becomes more interesting on the second example. I’m always playing with that conceptof ambiguity versus clarity. It can’t be too ambiguous because then you lose people. But if it’s too clear, it becomes another boring documentary. PBS has this mandate, which is to educate, inform and entertain. You can’t educate and inform without entertaining. So we’re always looking for ways to do all three of those things and this is the style we’re looking at.

HULLFISH: Speaking of style, there are editors that like to rip through an edit as quickly a possible and then go back and fine cut later and others that fine cut from the start. Which style are you?

AUDETTE: I’m always fine-cutting because I believe my director and I, as the editor, can see the potential of a scene no matter what state it is in, but I think that anyone else needs to see a fine cut. The problem is that they only know what they can see.

As we go through that fine cut I’ll make a QuickTime at the end of the day and send it to my director. He’ll make some notes and before we do the five pages for the day, he’ll have his list of changes. So you fine cut a little more. That process happens for five weeks before we start doing screenings. Our goal is to cut 10 finished – polished minutes a week. Most weeks we do better than that. So a 52-minute show is can be cut in 5 weeks. 90’s take a little bit longer and 180s push out accordingly. But I’ve been in the trenches where we bang out a great two-hour film in 6 weeks.

Early in week six we show the rough cut to the executive team. Then there is a week to ten days to address those notes. Then we show it again as a fine cut, after that the sequence gets locked with a final writing session and Will Lymans narration. Then the on-line post process begins for broadcast. The audio tracks are mixed in ProTools. The video is color graded in DaVinci Resolve, and packaged using Symphony.

Click “Next” below to continue reading the story.

HULLFISH: Getting back to the cutting itself, one of the things you use a lot is visual metaphors, buildings to stand in for institutions… various shots that the viewer needs to recognize as being representative, not literal.

AUDETTE: That’s actually a very important point. I try to never underestimate my viewers. In fact, one of the signs we have in our edit room is “Speak to peers.” When we’re cutting that kind of stuff we say, “Let’s not make it boring for them, but at the same time let’s make it visually interesting and have action to keep the pace up.

I’m always trying to make sure that I am making a visual environment that is compelling as the bed of the story. But for me, the audio is the story. The sound effects and sound design work that I do is an attempt to create a 3D world in which that story can live. It’s the only element that allows the universe to lift off the 2D world of the screen. So that narrative is being held up by a bed of beautiful stereoscopic sound and then on top of that are images that are compelling and cut well so that the mind’s eye can be drawn into the story. It’s all about details, every image is thought about and presented in a way that is consistent in the narrative and is consistent with the story we’re trying to tell.

HULLFISH: I loved some of the juxtapositions of one image to another or one sound-bite to another.

AUDETTE: The reason I think editors are a special breed is that we are becoming the masters of a new classical art form, and that is the art of motion picture editing. And the reason why a film editor for Hollywood, or a documentary editor in my case, is so valuable is because we are the masters of maximizing the Kuleshov Effect. Kuleshov is a filmmaker in Russia who came to realize that every image has two values. It has the value of the image itself and the value of the image it’s juxtaposed against. It’s that combination of two values that excites the imagination of the viewer to create a narrative. It’s just a small little thing, but if you add them up over time, it’s that cut to cut to cut that creates the narrative that the viewer experiences when they watch the film. That’s true whether it’s the news or Hollywood or a documentary or whatever. Hitchcock has a great example of this on YouTube.

HULLFISH: I want to point out an example in “League of Denial.” I was watching a scene where Dr. McKee, the female doctor, talks about going in to a meeting with the NFL and they treated her in a very sexist way. Then you cut to a guy trying to kind of defend himself from being sexist and he’s just stammering incoherently, because he’s trying to say that that’s not true, but by juxtaposing what she just said with his stammering, you’re making a statement.

sexism from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

AUDETTE: I’m also adding another layer on that. I always look for those Bernini moments. There’s this great architect/sculptor/painter and peer of Da Vinci who made these amazing sculptures of religious figures. And there’s one called “The Ecstasy of Saint Theresa” that’s just unbelievable. Her facial expression looks so alive. And he was once asked, “How is it that your sculpture is so alive and that the emotion is so evident?” And Bernini in effect responded, “I always wait for that moment before someone speaks or after someone speaks, to see the truth.”

HULLFISH: Wow! I love that. So true.

REWORK AUDETTE: Frequently in my cuts, I’ll try to add those moments where you can see this – I’ll hang on a subject as long as I can, even if it affects my pacing to some degree, because I’m trying to communicate something about what was just said. Is it something they believe with all their heart and soul? Are they just spinning us? Or maybe it’s an outright lie. But every sound-bite I cut into a documentary should be able to be played back to the speaker and have him/her say, “Yes that is what I was saying.”

HULLFISH: Some other great “holds” on facial expressions are the general counsel on the “United States of Secrets” show. At about 35 minutes Jane Mayer says “Roark is a very feisty woman. She was just certain that there was no way that this program was legal. And she said, “And if the NSA officials are breaking the law, I am going to fry them.” Then you hold on Mayer’s face for a long time so you see how she FEELS about what she’s just said. You see a kind of glee.

FryThem from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

AUDETTE: Precisely. That’s a perfect example of that.

HULLFISH: The other one is at 16:45 in “League of Denial” the ESPN reporter says “If Mike’s brain hadn’t been examined, we wouldn’t be where we are today.” And instead of saying (snapping my fingers like a cut) “Ok, we’ve got that bit of information, moving on…” you sit on his expression while he kind of stares down the camera as if to say, “Let that sit in folks.”

AUDETTE: Exactly right. Exactly right. And you see it in that extra moment of sitting with him that you realize how uncomfortable he was. As human beings, we are so good, most of us, at reading faces. I’m sure you feel like that in cutting dramatic stuff. It must be hard sometimes to cut away from these actors and actresses – to continue with the scene if they’re doing a particularly good job acting.

HULLFISH: Watch the movie “Brooklyn” if you get a chance. I interviewed the editor of that movie for an “Art of the Cut.” There’s a scene in that movie at a dance in Ireland where the lead actress, Saoirse Ronan, says something, and as she thinks about the implication of it, she realizes her whole life will change. And the editor stays with her, without dialogue, just watching her soak in this realization for what seems like a solid minute. It’s exquisite. There’s no data. There’s no speaking. There’s no voice over. She says something that is critical and now we’re watching as she soaks that in to her being.

HULLFISH: Love the “Bernini moment” concept.

AUDETTE: We are just starting to understand our art. I want to emphasize this idea that we’re becoming masters at a new classical art form – the art of motion picture editing. It’s only 100 years old, so it’s very new and fragile and fresh and we should take care with every cut we make so that we are maximizing the art of our craft, whether you’re a Hollywood, Indie filmmaker or a documentarian We have a responsibility to this new classical art of motion picture editing and we deserve to give it the best shot we can with every cut we make. I believe that with everything I am.

HULLFISH: Love it. Speak truth, brother! So you’ve cut a story together and now it’s time to show it to someone… that moment of truth when others watch this thing you’ve put together in a dark room.

AUDETTE: The first step is watching it ourselves as a group: the whole production team. In an hour long show on the first pass, I make about 50 or 60 notes. Mine are all about mix issues or sound effects or something wrong with an animation. They are, generally speaking, more technical than story structure at that point, because there are so many other people that deal with the story part of it that I tend to be much more technical: mix is too loud, mix is too low, pacing here is off, extra shot here, stuff like that.

The rest of the team watches and will say, “I got bored here. The film sat down at 40 minutes in and I don’t know why.” We then spend about two or three days fixing that stuff from the first screening. Maybe a sound-bite’s too long or it’s in the wrong order. Frequently, it’s too much narration. We need to thin the narrative down. Whatever doesn’t make the film entertaining to watch. Or, sometimes it’s “rabbit holes” which means we get too detailed about a certain particular part of the story that we get away from our story.

HULLFISH: Editors are always talking about pacing. There’s pacing inside of a scene, like “When do you cut off a close-up?” or “When do you cut to the next b-roll shot in a doc?” but there’s also the larger picture – the macro pacing: How it feels when a large portion of it, or all of it, is watched in one sitting.

AUDETTE: Very well said. Macro pacing is everything. One shot is all you get to bring a viewer through a whole film. Once we get it to the point where we’re pretty happy with it we show it to the executive management team and go through the same process. The most interesting thing, and I’m sure you have the same experience, is that it’s amazing to watch the film through the eyes of your executive producer.

HULLFISH: Absolutely. In my interview with Joe Walker, he described watching the film with a test audience as having a chemical reaction – Things takes on a chemically different feel when watching with a new audience.

AUDETTE: Just by them being in the room it changes things like you can’t even imagine. I love that experience of watching it through their eyes because it makes it extremely fresh for me. And it’s in THAT pass that I’m doing all of the narrative story stuff: pacing, rhythms, story arcs, and transitions. All those narrative storytelling things, We do this when screening with our executive producer, Raney Aronson-Rath. Her notes are very insightful. Generally speaking, it’ll be “I want more of this or I want less of this” and then it’s a process of going through the film and finding more or cutting without wrecking the story. And that can be tricky, but that’s the art of editing.

HULLFISH: I’m trying to figure out how deep into the chronology of post this screening is happening.

AUDETTE: With the Kirk team, we fine cut 10 minutes a week and if we don’t fine cut 10 minutes a week, we work the weekend. That includes a heavy amount of going back over all those daily notes, really polishing the edges. It is a very fluid process, so mapping it out like this is tough to make empirical. 52 minutes of content takes me about 5 weeks to get to rough cut. Early week six we screen with the executive team. After that screening we make their changes, which, generally speaking, are really good ideas. Then we have a fine-cut screening with them and it’s at THAT point where we tell the executive producer how long or short we are.

HULLFISH: (bursts into laughter) REALLY?

AUDETTE: Yeah. And the reason we wait that long is because we really don’t know what they’re going to want to add or subtract from the doc. I would say that the rough cut is usually eight minutes too long, the fine cuts might be four minutes long. The film I’m working on now is a two hour film and it was nine minutes long after the rough cut.

HULLFISH: This is a killer for me: Painful because you have something you like, but also exhilarating because of the challenge.

AUDETTE: All films, whether it’s Hollywood or Frontline or “House of Cards” if you start pulling at a thread, you might wreck it. So how do you know where to cut?

HULLFISH: I have the feeling you’re going to reveal your secret to us.

AUDETTE: This is something we’ve done over the years that is really, really effective and that is, we measure the length of scenes. And how we do that is not by how long they are in terms of minutes, but how much SPACE they take up on a script. We print the script and cut it out so it’s long paper chain, then we circle each scene. We immediately see which scene is too long. No scene in an hour-long show should be longer than the length of hand and a half. Story is a linear process. If that scene is taking up this much space, you can still truncate it without wrecking the story. The question is what do you take out of the scene? We shorten the sound-bite in that section. We take out the fluff over here. We take out the extra football footage.

At that point it’s fact-checked. And every single fact is annotated in the script. Fact checking changes the film a little bit too. And finally the film is ready to go to broadcast.

HULLFISH: And how does that process happen?

Click “Next” below to continue reading the story

AUDETTE: The WGBH OutPost facility takes my sequence and the video will go to an assistant editor who will up-rez the footage. The audio gets pulled out and sent up to a mix where he mixes in ProTools, using a QuickTime of the movie. Then the video is color corrected in Davinci Resolve and joined to the mix for our broadcast master. All of which usually takes about five days, soup to nuts.

HULLFISH: That’s my experience and timetable as well for on-lining a one hour doc.

AUDETTE: For us now, we send an OP1a to PBS for broadcast, the closed captioning is added. And that’s sort of the cycle of how we make documentaries.

HULLFISH: I’ve watched a bunch of Frontline’s and there’s definitely a style or feel to them.

AUDETTE: We always are trying to create a universe that a film lives in, in terms of its visual style and aural environment. Every Frontline documentary has a certain sound design to it and mine definitely do. Even when I go to a still photograph, I try to get the production assistant find me walla-walla, so that the photograph itself has life. The visual part, we really try to make the pictures make sense in terms of a visual thumbprint. If you go on line, you can see the visual thumbprint of “Star Wars” or “Black Hawk Down” you can see the colors of the movie, the color palette. And we do that too. We think about, “Is this scene going to always be at night?” or “Is there something we can do to enhance the emotional experience of the narrative with color correction?”

HULLFISH: Let’s loop back around to the front of the process again. When I’m cutting something that is documentary in nature, I tend to build what I call “the bones” of the film first. I want to HEAR what the interviews and maybe the narration sounds like strung into a story before I try to cover it with visuals.

AUDETTE: Depends on how long those string outs are. I’m not a big fan of stringing out a whole film. I want to know its rhythms and you can only really find that out by cutting scenes. I also really like to cut from the start. The hardest scenes to cut are the beginning and the end of a documentary. So I like to know I have at the start down. I’ve often said that I think of a documentary like bringing a dragon to life. Just like in books where if the first 15 pages don’t capture your interest you won’t read it, the same holds true for docs. Then we build the long neck the narrative that leads up to the body of your story. The body is where we have an audience so we can give this part of the story some substance. Then it is off to the end or your tale and the spikey tail of truth and understanding of this narrative. Once that is all laid out I find very often the dragon lifts it’s head and looks back at me, and now it is time to tame the dragon and keep it laying down in a straight line by cutting scene by scene until the documentary is done.

HULLFISH: What’s your approach to a scene?

AUDETTE: Generally speaking, a Frontline scene starts with narration. Very short. 20 words, 12 or 13 is probably perfect. I don’t like to put black holes in my film. If I’m going to cut narration, I want to know what I’m cutting it to. So frequently, even if I assemble an edit that’s just narration and sound-bites, I don’t much watch it: I listen to it so I don’t have to think about how ugly it’s going to look. So after I kind of do that first assembly of sound-bites where we say “He’s kind of boring and he’ll get truncated and we need to switch these bites and he’s going too long” the very next thing we do is say “What are we going to show here and what are we going to hear?” And by “hear” I don’t mean the narration or the sound bite, I mean, “What are the atmospherics? What is the sound design? And what is the visual image system of this scene going to start with?” Let’s get the interest level up. So we start building the interest level visually and aurally to contain the narrative. The bed on which the narrative is living is this visual system and this sound design. Also, by the pace of the narration I know I need three shots here, I can get away with two. I’m a firm believer in the fact thatcutting a scene is like building a fire – it’s like firewood: one won’t burn, two might, three will catch.I always try to build my shots in sequences of threes. Unless I’m deep into a story where I might be able to get away with two or one, but especially at the beginning of a scene to settle people into an environment they’re going to be in.

When I get to the first sound-bite, I truncate it. I try to get rid of the ums and ahs. I’m always trying to make people sound as articulate as possible. I try to clean up a sound-bite as much as I can without sounding false.

HULLFISH: While we’re talking about truncating sound-bites, I know you’ve discussed your use of the FluidMorph. This is an Avid term for a transitional effect at a cut that would normally be seen as a jump-cut – mostly in an interview bite. The FluidMorph can make this edit seamless. How do you justify the use of a FluidMorph journalistically?

AUDETTE: Well the Fluid Morph I’d say is the most slippery slope there is when cutting documentary. Story telling is an editorial process. What stays in and what gets cut out are based on good journalism and facts. If and ONLY if the jump-cut is in the same bite and I can find no practical way to place the audio edit under a scene will I consider a FluidMorph. What upsets me is when I see bad ones or when these morphs are made between two sound bites. If I have a guy on camera who talks with passion then says “can I start again? And picks up but drops out an important fact from the first go around, then I am OK with a morph otherwise stay clear.

HULLFISH: I’ve edited and produced several documentaries and I worked for a decade cutting “The Oprah Winfrey Show” which is largely interviews and talking heads. I cut the “insert stories” which are more akin to a sit-down doc interview. On “Oprah” there was always care taken in only showing the “talking head” (the person being interviewed) for a reason, instead of because you didn’t have anything better to cut to. You were on a talking head because there was a moment of personal revelation or emotion. And if you were utilizing two cameras on the talking head, you were conscious of when you switched to the close-up… not just to pace up the edit, but so that you were building to a close-up on an emotional moment or revelatory moment. In my interview with Eddie Hamilton, his opinion was that if you weren’t on the person when they said something critical – as opposed to a reaction shot in the world of drama – then the audience would forget that critical piece of dialogue, so that editor always played important information on the speaker, not the reacting actor.

AUDETTE: I think that’s very true. I tend to use the on-camera shot at the end of their sound-bite and use the cut to the next image as the “period” in their statement, whether that includes a pause before I cut away or whether I cut immediately.

HULLFISH: I’m like you. Almost always the most critical thing is to see them at the end. The other thing I want to talk about is that when you hear something in the narrative or there’s a part of the story where you finally have a dawning realization, or a revelation, you know that as an editor, you need to give the audience some space for them to process this thing.

HULLFISH: The other question we started talking about was the specific use of close-ups.

AUDETTE: Generally speaking, I think of watching shows on TV or the web as a very intimate experience, so I want to be close to see facial expressions. If they move their arms, I will definitely go wide. It’s action. I get a little visual interest and expression. I will always try to end the sound-bite on the close-up. I like to think like you’re in a salon of really smart people and you’re sitting there with them. How big is the frame of a person if you’re sitting in their salon, listening to their discussion or to someone tell a story?

USOS 911 from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

HULLFISH: I kind of agree. But I feel, sometimes that super-tight close-up is too much emotionally for the basic information you get in most headshots. Unless it’s really an emotional moment, the big, big close-up feels false to me. It’s too intimate. That’s similar to your salon example. If you’re sitting a comfortable social distance from even a close friend, you’re just not that intimately close.

AUDETTE: I agree with that. I just am so interested in the facial expressions of my characters that I’m more inclined to go to the close-up than the wide.

HULLFISH: But in the two docs I watched, you use that wide quite a bit. I felt you were on that comfortable wider shot fairly often. Are you only using that wider shot because you need to make an edit?

AUDETTE: I use it for body language. I don’t think I use it as a general rule because I don’t want people distracted by what’s in the room. For TV or because so much of what we do is seen on the web and there’s a smaller screen, I think it’s important to give people an opportunity to see the emotional content that is in the face that isn’t in the rest of the body. If it’s in the rest of the body, I’m going wide.

HULLFISH: When you’re pacing visuals – the individual speed of a series of cuts. I’m interested in when you cut. How fast does that sequence go? You could use one shot to cover a 20 second section of a scene or you can use 20 shots.

AUDETTE: Cutting those scenes are based on the rhythms of the voices of the speaking parts, whether that’s narration or talking heads. The cuts are inherently based on the pacing of the delivery of the lines of narration or talking heads. Also, if you’ve got a beautiful shot, you can stay on a beautiful shot longer. Frequently, to extend my ability to stay on a shot, I will do what I call an Avid push, zooming in anywhere between 10 and 30 percent. Human beings are attracted to motion. So if a shot’s too static, I’ll add a push. I’ll also do that on interviews. If I think a guy’s talking too long on camera I’ll add a push just to add interest.

HULLFISH: Joe Walker in his “Art of the Cut” interview might disagree with pacing the visuals to the rhythms of the voice. He said he cut visuals with the speakers turned off. But switching to another idea, I’m interested in creating mood or even using footage to make a statement in tone. An example of this for me was in “League of Denial” when Omalu makes a statement that the NFL doctors are out to destroy his reputation and actually accused him – a highly qualified medical doctor – of practicing voodoo. Omalu relates this and sits, stunned at the shock of the insult. And you cut to this moody, dark thunderstorm. The story itself at that point doesn’t specifically discuss a nighttime thunderstorm, but that’s what you chose to cut to.

Voodo from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

AUDETTE: With that cut, it was also the way he said it. He said, “They accused me of voodoo…” then he looks at the interviewer and says, “VOODOO!” with a pained, deeply hurt look on his face. And it was that emotion – the shock of that in Omalu ‘s face made me go to the scene that I used of a lightning storm in Pittsburgh where the event happened. I did it to relate the emotional shock with the lightning. And some would say that that’s a pun that should be avoided at all costs and normally I would agree, but in this case it was just so weird that I thought a scene of a little weirdness would make it hit home a little stronger. It was on purpose to accentuate the bizarre insult.

HULLFISH: I loved it. He was talking about the fact that these NFL guys went after his reputation and tried to destroy him, so I thought the choice of this storm closing in was perfect.

AUDETTE: Yeah. I wanted the tumult of that rainstorm to show how his life was crashing in on him. The whole scene is a series of emotional shots, every shot is juxtaposed to its next neighbor which furthers the emotional moment of the story. You know who’s great at this – of the cut telling the story: director David Mamet, who has a great book called, “On Directing,” which I recommend to all editors, because it discusses the power of the cut to move the narrative forward.

HULLFISH: This has been a fascinating interview. I’d like to continue this discussion in another article by jumping back and looking at the entire production process of Frontline. Maybe we can talk to you and one of your producer/directors and really dive deep into how these shows are conceived, pitched, created and delivered.

AUDETTE: I’d love to do that. Talk to you soon.

If you’re interested in more of these interviews, please check out the Art of the Cut page on ProVideoCoalition and follow me on Twitter: @stevehullfish. Steve Audette is also on Twitter at @stevecutsdocs You can also watch some of Audette’s tutorials on Vimeo.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now