As we begin the new year, it’s natural to look back on 2022 and reflect on the last twelve months. While Adobe continued to roll out new After Effects features and updates, the most notable change for me was upgrading my home office with a Synology NAS. This was something I had been planning for years – in fact I’d been thinking about it for so long I surprised myself when it finally happened.

Buying a new piece of hardware can be exciting. But depending on your circumstances, it can also be tedious, or nerve-wracking, or if you’re rushed into replacing something unexpectedly, just downright irritating. After years of procrastination, 2022 was the year I finally bought a “proper” NAS. When I was younger I would have found this incredibly exciting. Now that I’m older, it was a much more wearisome process.

Blog alert!

This article is not a review, or a benchmark, or even purchasing advice. It’s simply a personal blog of the thought processes I’ve been through over the years, as technology and working circumstances have changed.

Cheap, or fast, or reliable

The desktop video revolution, and non-linear editing specifically, was just emerging when I was at university in the 1990s. Desktop computers, by themselves, weren’t nearly powerful enough to play back video files. But pioneering companies such as Lightworks, Avid and Media 100 introduced revolutionary video cards that enabled a regular Mac or PC to play back “broadcast quality” video.

Hard drives were part of the problem. A single hard drive just wasn’t fast enough to read the data required for video playback. The solution was to use an array of multiple hard drives, to divide the workload and increase performance. This is generally referred to as a RAID – an acronym for Redundant Array of Independent (or Inexpensive) Disks. The computer treats the drives as one device – a single volume, just like a regular hard drive. But files are split up and spread across all the disks in the array, sharing the work of reading and writing, and increasing the overall speed.

Redundant Redundancy

RAID arrays were developed in the 1980s, as the home computer market grew rapidly. The lower cost of consumer devices made them economically viable options to traditional mainframe systems, however the corporate world demanded reliability.

In the business world, most important aspect of a RAID array is redundancy – meaning that no data is lost if a drive fails. Various types of RAID were developed that used different techniques to distribute data across multiple hard drives, with varying degrees of redundancy.

But as non-linear editing emerged in the 1990s, the redundancy that defined a RAID array was almost always overlooked. What video editors needed was raw speed – the fastest possible data rates – and redundancy simply slowed everything down. Non-linear editors were using RAID arrays without any redundancy because multiple drives were needed to reach the high data rates necessary for video playback. If a single drive failed, then all of the data was lost.

4 is the minimum number

Like all video hardware in the 1990s, everything was much more expensive than it is now. In 1995, in Australian dollars, a desktop RAID setup would cost you an even $1,000 per gigabyte. The 18 GB array we were first quoted on, comprised of four separate Seagate Barracuda drives, was $18,000.

Up until the mid 1990s, the largest hard drives available had a capacity of about 4 ½ gigabytes. That was as big as they got, but not really big enough for video. Video editing has always needed loads of storage, and so typical editing systems from that time used a RAID with at least 4 drives, for a total capacity somewhere around the 18 gigabyte range. Having 4 drives in the array also guaranteed fast transfer speeds, along with the headaches associated with SCSI – different types of SCSI, SCSI IDs, temperamental SCSI chains, and breathtakingly expensive cables. If you could afford it then you could have more than four drives in your RAID – but that also increased the risk of a single drive failure bringing down the entire system.

This was my first introduction to the concept of a RAID. In 1997, the Media 100 system that started my career seemed like an expensive and exotic piece of technology. There was no option for me to work from home – my job revolved around the expensive, and therefore exclusive, collection of computer hardware at the office.

But the first impression had been made: a RAID meant speed.

Working in Isolation

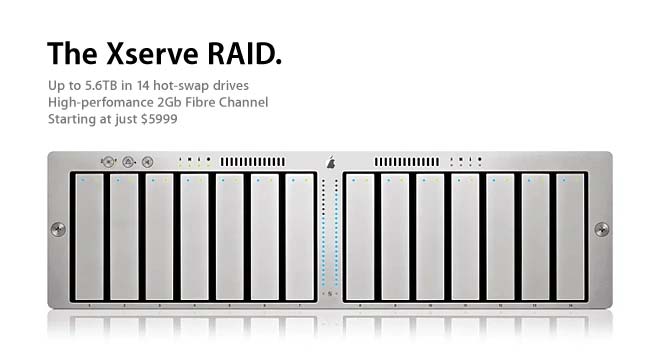

Ten years after my first introduction to a Media 100, software and hardware looked a bit different but the underlying technology was based on the same principles. Editors had migrated towards Final Cut Pro, and products such as Apple’s Xserve RAID had emerged to make high-speed storage simpler and more attractive.

Hard drives had improved so much in price and performance that redundancy became a feasible option, even for editors. The Apple Xserve RAID held a total of 14 individual hard drives, but two of those were redundant – so even if a drive failed, data wasn’t lost. Editing suites were now measuring storage in terabytes, not gigabytes.

By the mid 2000s, RAID arrays were larger, faster and cheaper than ever before, they were still – usually – directly connected to a single computer. Having multiple edit suites / computers share the same RAID required a significantly more costly and complex setup. The first shared RAIDs were based on expensive and slightly volatile fiber-channel technology, and became known as SANs – a Storage Area Network. But an alternative approach to the same problem also emerged – the NAS, or Network Attached Storage. A NAS wasn’t as fast as a SAN, but it was based on cheaper, existing Ethernet technology.

I’d been to several industry events promoting early fiber-channel SANs, and the overwhelming impression I got was that they were incredibly expensive and surprisingly unstable. If the vendor couldn’t get it to work properly at a public exhibition then what hope did a regular editor have? But despite the pain that evidently accompanied early adopters, it was clear that having multiple computers share the same pool of storage was more sophisticated and potentially MUCH more productive.

While the underlying technology behind a SAN and a NAS is quite different, for the end user the only distinction is that a SAN appears as a local drive, while a NAS is, by definition, connected to via a regular Ethernet network. Gigabit Ethernet was well and truly established by the mid-2000s, and offered theoretical speeds of up to 125 megabytes per second – more than enough for video editing.

The drives they are a changin

But on a personal level, by the mid-2000s I was now working as a freelance motion designer, and I was starting to think about keeping copies of projects that I’d worked on. Previously, as an editor, keeping a copy of a project meant mastering an extra copy to tape – and somewhere in my garage I still have a box of Betacam tapes dating back to 1997. But working as a motion designer in After Effects meant that instead of tapes, now I wanted copies of After Effects projects and Quicktime files.

Hard drives had continued to drop in price, and companies such as LaCie had released portable hard drives that found an immediate market in the film and television industry. LaCie’s first external drive was released in 2003, in both 400GB and 500GB sizes. With the 400GB model retailing for Aus$1,900 and the 500GB for Aus$2,255, this worked out to be just over $4 a gigabyte. This was massively cheaper than the $18,000 we were quoted for 18 gigabytes of storage back in 1996! Having this capacity in a small, portable form factor was ground breaking.

Over the next few years prices continued to drop, capacities increased and other vendors bought similar products to market.

Big Assets

The first decade of the 2000s saw the emergence of motion graphics as an essential tool for corporate communication, while digital visual FX were changing the way that Hollywood made films.

The rapid adoption of motion graphics and animation resulted in huge amounts of data being generated, with individual projects easily capable of taking up hundreds of gigabytes, if not terabytes, of storage.

For the average agency, and smaller studios, the issue of backups and archiving was often either overlooked, or simply ignored. Perhaps the bigger problem was that the cost of storage was cheaper than the cost of human labor to go through projects, sort them out and consolidate them.

A quick Google search suggests that buying a 1TB portable hard drive right now, costs roughly the same as hiring a senior artist for 1 hour of work. The cost of 1TB of storage for a larger NAS, or even a tape-based archive, is even lower. And once a project has been completed and delivered, no-one ever feels like sifting through it and sorting it all out. It’s almost a no-brainer.

“Archiving” a project just by copying everything to an external hard drive, or even a tape drive, is relatively cheap on a per-gigabyte basis. It was – and still is – common practice to copy entire project folders, complete with redundant test renders, previews, WIPs and so on, simply because it’s easier than the tedious – and potentially expensive – process of having artists sort through their own work manually and decide what needs to be kept.

The basic problem of archiving hasn’t changed and still exists today. The cost of employing someone for just 1 day is still much higher than the cost of storage. Once a project has been completed, it’s still cheaper and faster to just copy everything rather than go through it and try to make some sort of meaningful backup.

Not my problem

Working as a freelancer, I might be booked for a few days, a few weeks, or a few months at one studio, and then finish up and start working somewhere else. Using a portable hard drive was the simplest way to keep copies of my work as I moved between different companies.

But even approaching 2010, the cost of computer hardware and software was still high enough that working from home was uncommon. Video cameras still shot on tape, tape decks were a necessary evil that cost as much as an apartment, and in general the setups required for working with digital video from home, while collaborating with a studio, were too expensive for an individual.

Software wasn’t a subscription service, but something you paid a lot of money for on an annual basis. So while working as a freelancer, the onus and responsibility of providing capable hardware and software lay firmly on the studio’s side. The same was true for backups and archiving. Larger studios could afford to have a tape-based backup system and someone to operate them, smaller studios just kept buying external drives and popping them onto shelves to collect dust.

Data Robotics: Beyond RAID

As I continued to work as a freelance motion designer, the number of portable hard drives I bought to store all my work steadily increased. I was not alone – everywhere I worked had shelves of portable hard drives, some labeled, some not, but all full of unsorted projects spanning years. Any time a client called up hoping to revise an older project, or reuse existing assets, a quiet panic would ensue as portable drives were collected from dusty shelves and plugged in one at a time, searching for the right project.

In 2007 a new product was released that immediately caught my attention. Called the Drobo, this was an external storage device that could hold four hard drives. The Drobo had a number of features that made it unique and especially appealing to home users like me.

Firstly, the Drobo offered expandability. Instead of buying a single, external drive and then filling it up and buying another, you could buy drives as you needed them. The Drobo had four hard drive bays but you didn’t need to fill all four drives in order for it to work. You could start with just one drive, and then when that was full you could add another, and then another. Because you weren’t paying for a new case and power supply each time, overall this was cheaper than buying four individual portable drives.

Secondly, the Drobo offered redundancy. The biggest problem with collecting shelves full of external, portable hard drives was their fragility. If the drive stopped working, which was common, you lost all of your data. But the Drobo used multiple drives as a RAID – with redundancy meaning that one of the drives could fail and you wouldn’t lose everything.

Finally, Drobo had their own proprietary form of RAID that allowed the user to mix and match hard drive sizes, and even replace smaller drives with larger ones. Previously, anyone setting up multiple drives as a RAID needed to use identical hard drive sizes, and once the RAID had been set up then that was it – the capacity of the RAID was set and couldn’t be changed. Traditional RAIDs were fast and offered redundancy, but they weren’t flexible or expandable.

But the Drobo changed that. You could mix hard drives of different sizes, and if you filled up all of your storage then you could take out one of the smaller drives and replace it with a larger one. At the time, this was a really innovative solution that seemed to tick every box. Data Robotics called it “Beyond RAID”.

Drobo: 4 bays of disappointment

The first Drobo was released in 2007 and seemed to be a brilliant solution to so many problems. Around this time I’d bought an iMac and was doing small After Effects projects from home. I was seriously considering buying a Drobo, however I’ve always been wary of first generation products, and as my iMac had a new Firewire 800 port, I would have preferred something with a Firewire 800 connector. Even though I was working as a motion designer, a lot of my work still involved video editing, and so I wanted something fast enough to handle video playback.

At the start of 2008 Drobo announced their 2nd generation product, which seemed to be pretty similar but included a Firewire 800 port. But they also had another incentive. I can’t remember the exact details, but if you pre-ordered the new model you’d also get something called a “Drobo Share” for free. I didn’t know what a Drobo Share was, but they were selling them separately for a few hundred dollars. The idea of getting one for free seemed like a good deal. So I took the plunge and ordered a Drobo with three 1 terabyte drives.

It was OK, I guess.

In fairness, the Drobo did everything that it promised it would do. It offered redundancy, so I didn’t have to worry as much about data loss. It was expandable. I started with 3 drives and added a forth when I needed to. And then, when I started to run out of storage again, I slowly replaced the original 1TB drives with 2TB drives. It worked.

But unfortunately, it was just slow. Really, unexpectedly slow. I still had my original assumption from 10 years ago that RAID = speed. The early non-linear systems I used all needed RAID arrays in order to work. The RAID that came with our Media 100 was a solution to the need for high data rates. But even though it came with a new Firewire 800 port, the Drobo simply wasn’t fast enough to use with video editing software. It wasn’t just the transfer speed, but overall latency. It just seemed to take a long time to do anything.

More annoyingly, the drives in the Drobo would power down to save energy if they hadn’t been used for 15 minutes. But it would always take a noticeable few seconds for them to spin up again- which they’d do any time the computer needed to access a file on any drive, or even open a file browser. This was much more irritating than I can accurately describe, and unfortunately this could not be disabled on my model (the next Drobo model allowed you to turn energy saving off, but I was stuck with it).

As for the Drobo Share… I find it interesting to look back on it now. I never used it. I never really understood what it was. It’s a symbol of my technical ignorance from that time. In 2008 I just didn’t know what a network drive – a NAS – was.

If you’re curious, then the Drobo Share was a small device that turned your Drobo into a NAS. Instead of connecting your computer directly to the Drobo by a Firewire or USB cable, you could hook up the Drobo share and connect to it over Ethernet instead. The Drobo Share contained a small ARM-based server and was capable of running basic apps, just like modern NAS devices are today. It allowed multiple computers – Mac and PC – to access the Drobo simultaneously.

To me, I didn’t really get it, because in 2008 I just hadn’t worked anywhere with a NAS before. Thanks to Apple’s marketing, I assumed that Firewire 800 was super fast and it never occurred to me that it might be slower than Gigabit Ethernet (800 is less than 1000 – Gigabit Ethernet is faster!). Because I only had one computer – my iMac – I didn’t have any need to connect another computer to it. So it just sat in a drawer somewhere.

If I’d understood what it was, then maybe I would have used it. But I remember thinking – why would I want to use a separate box to connect a hard drive with a network cable, when I can connect it directly using Firewire 800 instead? It just seemed like trouble.

I meant to sell it, but I never quite got over the feeling that it might be useful, one day (it wasn’t).

SSD: Seeing the future

A few years later, my iMac began to feel a little old and slow, and I was looking for ways to make it faster without simply buying a new one. SSDs had been around for a few years, but they were very expensive. But if reports were to be believed, then the high price was worth it. They cost a lot, but an SSD was still cheaper than a brand new iMac. I decided to try one for myself.

Rather than buying a whole new iMac, I replaced the original spinning hard drive with a new SSD. This was around 2012 and was pretty radical at the time – I had to buy some custom tools, a custom mount for the SSD to fit in the iMac’s hard drive slot, and carefully follow a set of instructions I found on the internet. Taking apart an iMac is not for the uninitiated.

But it worked, and the result was revolutionary. My iMac didn’t just feel faster, it felt supercharged. It was faster than the newest iMacs. I became an instant SSD evangelist. I couldn’t believe how much the spinning mechanical hard drive had been holding back the rest of my computer. I had seen the future and the future was SSDs. And not only were they so much faster than a traditional hard drive, but it felt like they were so much more robust and reliable. If a SSD didn’t have any moving parts, then it must be much less likely to fail, right!

Moving into the garage

Despite my disappointment with the Drobo’s speed, and its irritating ability to bring my entire computer to a halt every 15 minutes, it served its purpose for many years. But I got to the point where I’d filled up the four bays with 2TB hard drives, and yet once again I was still running out of space. It felt like every project I worked on was using up more and more storage.

Some time around 2015, I was at the local office supplies shop and I saw that portable hard drives were now available in 8GB sizes. One single drive, costing roughly $400, could now store more than my entire Drobo with its 4 drive RAID, and it would probably be a lot faster too! I bought one, and the Drobo was unplugged and moved into the garage, next to my box of Betacam SP tapes.

I was well aware that my new drive offered no redundancy, but I reconciled myself with the thought that if it failed, I still had most of my archives on the Drobo. It would only be newer projects that I’d lose. But I knew it was time to look for something else.

Looking beyond Beyond RAID

While I’d bought a Drobo because its unique features appealed to me, Drobo definitely weren’t the only manufacturer selling storage products to consumers. Other well known brands included LaCie, Western Digital, Qnap and Synology.

Perhaps because it was noisy, and when the drives powered down and then spun up again they produced all sorts of clicks and thunks, the Drobo was a constant reminder that hard drives were a mechanical device. My experience with the SSD in my iMac convinced me that SSDs were the future. Spinning drives just seemed… old fashioned.

There was still a notable gap between the types of storage used by individuals and the larger enterprise products used in studios and production facilities. In 2017 you could go into an office supply shop and buy a 1TB portable hard drive for roughly $100. But 1TB of storage for a high speed enterprise SAN could still be well over $1,000. The types of servers, switches, hard drives and overall network / storage infrastructure used by a room full of motion designers and visual FX artists was still a world away from anything you’d buy at the local mall.

Having worked in many different studios, I’d become aware of how important bandwidth and network speed is for After Effects. Every studio I worked at now had some form of shared network storage, and several of them had render farms (which I considered a great luxury). But every studio I’d ever worked at used gigabit Ethernet, which had a theoretical maximum data rate of 125 megabytes per second. After Effects, and non-linear editing software, could easily process data at a faster rate than that. It was simple to measure the difference in render times between local rendering and network rendering, demonstrating that the slowness came down to data transfer speeds, not After Effects.

I had begun planning my series on “After Effects and Performance”, and a significant aspect of the series was the focus on bandwidth, and appreciating just how much data After Effects could churn through. It was slightly annoying to hear the recurring mantra “After Effects is slow… After Effects is slow…” when it was actually the studio’s gigabit network that was holding everything back.

While many artists were happy to throw lots of money at expensive GPUs to help speed up their 3D renders, not many people stopped to think about how faster storage could help improve their 2D renders. The cost of a SSD was lower than the cost of a high-end GPU, and for anyone doing primarily 2D work, buying a SSD instead could have a bigger impact on rendering speed and performance.

But SSDs had their own problems – most obviously price and capacity. Compared to a regular spinning hard drive, they cost a lot more and they stored a lot less.

No rush to go backwards

Even though my Drobo had been resigned to the garage, I wasn’t hugely motivated to replace it. While I had prolonged the life of my iMac by installing the SSD, a few years later I had transitioned to a new Windows box. It had a high-speed internal NVMe SSD, which was the main drive I worked from. NVMe drives are even faster than the SATA drive I’d used in my iMac, and it could transfer data around at about 1500 megabytes per second. At the time I bought it, this was about as fast as regular SSDs got.

As a comparison, regular gigabit Ethernet topped out at about 125 megabytes per second, more than ten times slower. Even the USB-3 standard had a maximum theoretical speed of 625 megabytes per second, and real-world speeds would be slower.

So any sort of external drive that I purchased would be slower – much slower – than the internal SSD that I was used to. Also, because I didn’t do a lot of work from home, I wasn’t exactly running out of space. I just worked off my internal SSD and then when projects were finished, I copied them to my external drive.

There was no incentive for me to look for a replacement for my Drobo when anything I bought would be slower than the system I was currently using.

Flash… ah ahhhh

Although I’d been a relatively early adopter of the Drobo, I’d never really paid any attention to alternatives. I half-knew that eventually I would need something similar, but I still felt a bit burned by the poor performance of my Drobo.

I’ve always gotten along well with IT support staff and other techy people in general, and one day when I was working at a studio their head of IT asked me if I wanted to see “a new toy” that had just arrived. He showed me a nice looking black box that wasn’t quite big enough to be a computer.

What I was looking at was a brand new Synology NAS, simply called the FS1018. Synology had been producing NAS devices for consumers for many years, directly competing against Drobo with arguably more powerful products. I was vaguely aware that companies like Synology and QNap existed, but because I already owned a Drobo I’d never paid much attention.

But the FS1018 was an interesting new development. The FS stood for Flash Storage. This was a NAS that was designed specifically for SSDs. Here was a relatively small desktop RAID with a consumer(ish) price, capable of holding twelve SSDs without a single spinning hard drive in sight. SSDs were already blazingly fast – but 12 of them together in a RAID? Surely that thing must be FAST!

The studio’s IT head obviously thought so too, and was in the luxurious position of being able to buy one simply to find out. The studio specialized in live events, and artists were routinely dispatched to various countries around the world to work on-site. The FS1018 looked like the perfect portable solution for a small number of artists working together in a remote location.

I immediately felt that this was the product I’d been looking for. No more issues with speed, no more issues with clunky spinning disks powering down and then up again. I had been worried that an external drive would be slower than the internal SSD I currently used, but surely this would be a match!

My experience in upgrading my iMac had been such a revelation that I never thought I’d buy another spinning hard drive again. I loved SSDs, and finally here was a desktop RAID designed around SSDs in a cool looking box.

Budget

But the bigger problem was price. The base FS1018 unit was reasonably priced, and no more expensive than a comparable desktop NAS that used spinning drives. However the SSDs you needed to put in the thing were still frighteningly expensive. At the time, the largest (conventional) SSDs were 2 TBs in size, a lot less than the largest spinning disks. But the FS1018 could hold 12 drives, so filling it with 2 TB drives would result in just under 20TB of usable space, once you accounted for formatting and redundancy. 20 TB seemed like loads to me.

I quickly estimated that buying one and filling it with 2TB drives would cost over $12,000. I didn’t have $12,000 to spare, and even if I did, it seemed like an awful lot to spend on a fancy hard drive. But SSDs were dropping in price, and I followed the same logic I had when I bought my first Drobo – I didn’t need to fill it up on day 1. I could start with three drives and add more when I needed to.

The Synology FS1018 was, in a relative sense, a consumer level device. It was vastly cheaper than an industrial SAN / enterprise level NAS, but with a level of performance that should easily support several users. I understood why our head of IT was intrigued by it. Thanks to the speed of SSDs, especially configured in a RAID, the performance was incredibly attractive for the price. And it was reasonably portable. It was certainly an interesting option for anyone who’d been considering more complex, enterprise level solutions for a small studio. $12,000 is a lot of money for an individual to spend on 20 TB of storage, but if you’re running a studio that’s spent more than ten times that amount on an enterprise SAN then it doesn’t look like much at all.

When Synology released the FS1018, I hadn’t looked around at any other options. I didn’t even know where to start. But some basic Googling confirmed that the Synology FS1018 – at that point in time – didn’t have any direct competition. Every other NAS device on the market used spinning drives, even if some of them could utilize one or two SSDs for caching. I was so convinced that SSDs were the future that I just wasn’t interested in anything that used spinning drives. In 2018 Synology were the only company offering a NAS built solely with SSDs. It seemed to be what I was looking for. I decided I wanted one. I just had to figure out how to pay for it.

I gave this some thought and devised a cunning plan. I would come up with a budget and plan ahead. I wasn’t used to being this mature but it was worth a shot. It’s quick and easy to set up an online bank account and make an automatic transfer each month.

About ten years earlier I’d been reluctant to buy a first generation Drobo, and now I was reluctant to buy a first generation FS model from Synology. I figured that by the time Synology released an updated model, I’d be ready to buy it. For the time being, I could survive with my 8TB external drive and just pray it didn’t die.

Covid

When Covid spread across the globe it changed everything for everyone. Amongst other things, it stopped me from making an expensive mistake. I didn’t buy the Synology FS1018.

Like many other people, the most immediate impact of Covid was that I began to regularly work from home. Working from home changed a number of my priorities. Firstly, I noticed that I was using up much more storage than I was used to. Before Covid, working as a freelancer meant travelling to different studios and using their equipment – and their storage. Any archives or backups I kept were usually project files (pretty small) or a selection of “final” quicktimes. I had archives from about 20 years of work that fitted neatly onto an 8 TB hard drive.

But now, working from home, I was finding that individual projects could take up anything from 100 gig to 1 TB. I was running out of space, and fast. It felt like I had time-warped back over 10 years, with a desk full of portable hard drives that I’d plug or unplug as I needed them. In a few cases studios had couriered portable hard drives to me with footage on them, and I ended up using the same drives to work from, because I didn’t have the internal space to copy everything over.

Working from home also made me responsible for the data I was producing. I became worried about losing projects from a hard drive failure. I had visions of a storm causing a blackout, and not only losing time working – but then discovering that my drives had become corrupted by the power failure. I used some of my existing budget to buy a UPS, so if the power did ever go out, I’d be able to save everything first and shut down my system gracefully.

As the industry reeled from the effects of the Covid pandemic, projects slowed down and so did income. Just like everyone else, I had no way of predicting the long term economic impact that Covid would have on our industry.

It did not seem like a good idea to be spending thousands of dollars on new hardware.

I found myself in a frustrating situation. I was in a position where I simply did not have enough hard drive space to be able to do my job, yet I didn’t feel like I was ready to spend thousands on a long-term solution. But just going to the mall and buying yet another portable hard drive to work from seemed like the wrong move.

Western Digital: 2 Bays of good luck

With a stroke of good luck I stumbled across an agency that was closing down and selling everything – including chairs, tables, lots of iPads and a few hard drives. They had a 2-bay Western Digital NAS which had hardly been used, and they were selling it at a bargain price. It had 2 6TB drives in it for a total of 12TB storage – but the drives could be configured as RAID 1 to offer redundancy. It was an opportunity to buy an entry level NAS for less than the cost of a new portable hard drive. It felt like a good short-term solution.

Even though it was a pretty simple device, the Western Digital NAS suited me perfectly. I was relieved to have some level of redundancy so that I wouldn’t lose everything if a drive failed. It was a good introduction to what a NAS is, and how they work through web-based interfaces. I bought a $50 network switch and was able to get my Mac and Windows machines to connect simultaneously – something that was so seamless and productive that it made me wonder if I should have persevered with the Drobo Share all those years ago.

I regularly have After Effects projects rendering on my Windows machine while doing Syntheyes tracking on my Mac. Both machines are reading the same files on the same folder. It works so well, and so seamlessly, that I can’t believe I spent years copying miscellaneous files onto USB sticks to move them around. My home setup now had the same level of functionality that I expected of all the studios I’d worked for. It felt good.

And finally, one more thing that Covid changed was spare time. As projects and work in general dried up, I took the time to sift through all of my old drives, and sort everything out. I knew the Western Digital NAS was just a short-term solution, but I figured that if I started to get organized then when I did buy something more permanent, I could just copy everything across.

This is not the NAS you are looking for

I had never paid much attention to the NAS market, and until I saw the FS1018 I didn’t know much about Synology. My assumption was that they would update their products regularly, just like other tech companies did. I felt that the biggest shortcoming of the FS1018 was the lack of 10gig Ethernet – how could a network device that was so fast not have 10 gig Ethernet built in? There was always the potential for an upgraded model to come out with more RAM, a faster CPU, and 10 gig Ethernet as standard. That 2nd generation model would be the one for me.

Every now and again, I checked the Synology website to see if there was any news about updates. Over time I forgot. Synology didn’t seem to update their products very often, and as it wasn’t a priority of mine I would forget about it for months on end. I wasn’t exactly desperate to spend a lot of money. Eventually – after several years – I finally saw the press release I’d been waiting for. Synology had released a new FS unit.

But the upgrade – if you can call it that – was not what I expected.

Around the start of 2022, Synology released a new entry-level model in their FS range, the FS2500. But this was not an upgraded version of the FS1018 – it was a higher specced replacement. The FS1018 was discontinued.

The new FS2500 is a rackmount device, not a desktop box. It is more powerful than the FS1018 in every way – faster CPU, more RAM, built-in 10 gig Ethernet. It even has redundant power supplies.

But the price reflects this – the base unit is more than twice the price of the older FS1018. The FS2500 is not a device for a single user working at home. I still think it’s an interesting option for small studios, and it’s still an economical alternative to enterprise level NAS and SAN systems. But it’s not a consumer-level device.

For the past few years, my bank had been automatically putting money aside each month for new hardware. But now the hardware I’d been saving up for had just been discontinued with no immediate replacement. It was time to look for a different solution.

Spin you right round

I originally wanted a FS1018 because of an assumption. I simply assumed that SSDs were the future, and spinning disks were old fashioned. And apart from looking around to see if other manufacturers had SSD-only products, I’d never done any actual research.

My other assumption was that any external device would be slower than the internal SSD that I worked from – this was also why I was reluctant to actually buy anything.

But as the FS1018 had been discontinued, I needed a new plan, and for the first time I looked for advice. I asked friends, work colleagues, checked online reviews, and started watching lots of YouTube videos posted by NASCompares – an invaluable resource.

Very quickly I realized that some of my base assumptions were simply wrong. Firstly, it was clear that spinning disks had a long future ahead of them, especially on a cost-per-gigabyte basis. But – more surprisingly to me – the speed difference between an external NAS and my internal SSD mightn’t be as big as I expected.

In regular, everyday usage my internal NVMe SSD benchmarks at about 1,500 megabytes per second. But 10 gigabit Ethernet has a theoretical maximum of 1,250 megabytes per second. The difference isn’t that huge. And although I was concerned that spinning disks were so much slower than a SSD, most NAS boxes could use SSDs as a cache to increase speeds. And the more drives that are used in the NAS, the faster the transfer speeds.

So working 10-gig Ethernet into the equation, moving from an internal NVMe to an external NAS shouldn’t be as painful as I had first thought.

But it was the difference in capacities that finally sold me. SSDs have gotten larger and cheaper, but so have spinning drives. When I first looked at the FS1018, the largest regular SSDs were 2TB. Now, 4TB SSDs are common. But spinning hard drives were also getting larger and cheaper. For the same price as a 4TB SSD, you could buy a 14TB spinning drive.

Now that I was working from home, I needed a lot more storage than I used to. Four years ago I thought that 20TB of storage would last me for the foreseeable future. Now, I probably had that much lying around my desk on various portable drives.

Buying a NAS that only used SSDs was no longer realistic.

Cache in hand

Many NAS reviews that I looked at asked whether model X was suitable for 4K editing. It sounds like lots of video editors are interested in NAS reviews, and I can understand why. I always paid attention to these because I felt like people working with 4K video had similar requirements to mine, but with one exception.

Although the average desktop NAS uses spinning drives, many of them also have the option to use an SSD as a cache, which can obviously transfer data much faster. Because After Effects has had a disk cache for so long, I was familiar with the concept and assumed that an SSD cache would work the same way. Commonly used files would be cached on the SSD and could be accessed and transferred much faster than from the spinning drives. This would improve latency as well as raw data rates.

But when it comes to video editing, especially people working with larger video files, then a number of reviewers suggested that a SSD cache makes little to no difference. The problem with video editing is that footage files can be so large that only a few clips can quickly fill up the cache, negating its usefulness.

I could understand this, as I’ve worked on projects where individual takes from hi-res camera have ranged between 20 to over 100 gig each. When your SSD cache is only a few hundred gig in size, but you’re dealing with individual files that average about 50 gigabytes, then it’s easy for the cache system to get overwhelmed.

But in my case, the majority of the assets I work with are EXR sequences. While I am regularly supplied raw camera rushes that can be HUGE, the first thing I do I convert the selected clips to trimmed EXR sequences. Dealing with lots of small files as opposed to one giant file is exactly what caches are good for. While I noted the online warnings that SSD caches are not a good thing for all video editors, I decided than an SSD cache would be very useful for anyone working with 3D and motion graphics.

3 new problems

For several years I’d been waiting to buy an upgraded SSD-only NAS, but now that wasn’t an option I needed a new plan. And I needed to act quickly, because even my new-ish Western Digital drive was almost full. It would only be a few months until I was back in the situation of not having enough drive space to work with. For the last few years I’d been waiting on Synology, but now that plan was out the window there was no reason to wait any longer.

In trying to work out what to buy, I realised I had 3 basic decisions: What type of NAS, what type of drives, and what type of 10 gig network switch.

In some ways, the NAS was the easiest decision. I was in the market for a regular desktop NAS with spinning drives, and there’s loads of information and reviews covering the desktop NAS market. People seem to love reviews and the internet is happy to provide.

Overall speed was still my main priority, as I was dreading the backwards step from my internal NVMe drive. So I started by looking at desktop NAS units that had 10 gigabit Ethernet. In terms of redundancy and capacity, I figured I would need at least 6 drives. I was always planning on setting up the NAS with 2 redundant drives, and so a 4-bay NAS would have been too small.

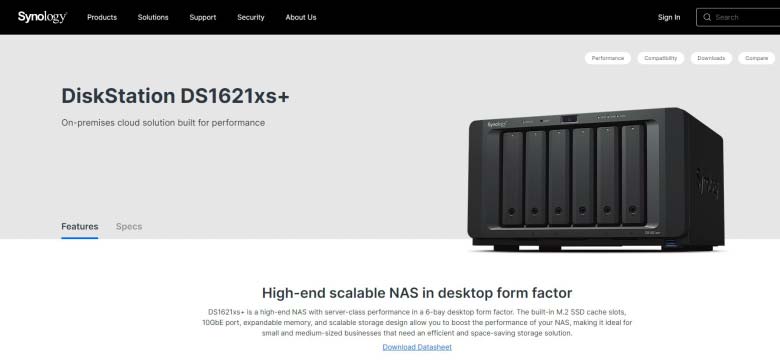

Searching for a 6-bay NAS with 10-gig Ethernet quickly revealed the Synology 1621xs+, and it seems like a pretty good device. There are loads of positive reviews and it got the thumbs up from the NAS Compares YouTube channel. But in doing some basic research, I discovered that this was a premium version of the more basic 1621+ (the one without the xs). The Synology 1621+ did not come with as much RAM, or 10-gig Ethernet, but you could upgrade it so that it did. Once you beefed it up a bit to match the specs of the 1621xs+, the cost was actually about the same. This was a little frustrating, because I would have expected Synology to make the xs+ version a little more appealing. If the price difference between the 1621xs+ and the 1621+ with all the extras added on was more significant (ie. if the xs+ was cheaper) then I would have bought it.

Linking Aggregates

I was still paranoid about overall transfer speeds, and when I was chatting about this to one of my friends, he suggested that I look into link aggregation. Link aggregation is where devices use multiple network ports to increase their transfer speeds. It’s a bit like RAID but for networks. Network data is spread out over multiple ports and sent over multiple cables, increasing the overall transfer rates. Using 2 ports can double speeds, 4 ports can quadruple them and so on. While 10-gig Ethernet has a theoretical top speed of about 1,250 megabytes per second, by using link aggregation and 2 network ports, this can be doubled. 2,500 megabytes per second is on par with high-performance NVMe drives and compared to my older SSD, it’s even faster.

To me, this was great news. The fear of upgrading my system but having everything go slower was starting to fade. Link aggregation seemed to solve my prayers – but there was a problem. Link aggregation is only supported on higher-end switches. I’d need a managed switch, not just a basic generic model. I already knew that if I bought a 10-gig Ethernet device I’d have to upgrade my home network switch to a 10-gig Ethernet model, but it wasn’t going to be as cheap or easy as I hoped.

Although the Synology 1621xs+ came with a 10-gig Ethernet port as standard, it only had one port. This ruled out link aggregation. Alternatively, if I bought the cheaper 1621+ model I could install a dual-port 10-gig network card. This would give me the option for link aggregation, while being cheaper overall. It seemed like the better choice.

And then, thanks to internet reviews, I realized that Synology also made an 8-bay NAS called the 1821+. It was essentially the same as the 1621+, but it had an additional 2 drive bays. The cost difference was pretty small. By the time I added up all the extras – including 10-gig Ethernet card, more RAM and SSD cache – the total cost of the souped-up 1821+ was about the same as the 1621xs+, but I had an extra 2 drive bays.

I asked one of my trusted friends – Is there any reason not to get an 8-bay instead of a 6-bay? And his answer was – always go for the most bays. It made sense. I was purchasing this device for the future. I hope it lasts me more than 7 years. Having 8 bays not only allows for more capacity, but also higher speeds. Having 8 drives do the work is faster than 6.

So by following that chain of thought, I had decided which NAS to buy – the Synology 1821+, which I would upgrade with dual 10-gig Ethernet.

I’ll add that I did check out other brands and comparable products, and I looked especially closely at the Qnap range. But ultimately, I settled on the Synology.

Driving you up the wall

I didn’t know that there were so many options with hard drives until I went to buy them. Apart from the various brands, including Seagate and Western Digital, there were various ranges. Western Digital have 6 different ranges of hard drives, named after colors. Seagate have several options too, including their “Ironwolf” range. But some drives were designated “Pro”, others “Enterprise” and others just “NAS”. What was the difference between a “NAS” hard drive and an “enterprise” hard drive? I had no idea.

What was more confusing was the price. It seemed as though every time I checked the price, it was different. Hard Drive prices seemed to fluctuate more than the stock market. And often it didn’t make sense. To me, it sounded like an “enterprise” hard drive should be more expensive than a more basic “Pro” hard drive – but often they weren’t.

I didn’t get it.

For months I found this intensely confusing. I read articles and watched YouTube videos, and found some consolation that many others were just as confused as me. Apparently, because “enterprise” level hard drives are purchased in such large numbers by data centres, they often end up cheaper than the hard drives that are aimed at consumers. The price fluctuations represent current market supply and demand. As counter-intuitive as it sounds, the cheaper hard drives can be better options than the more expensive ones.

At some point, I started leaning towards the Western Digital “Gold” drives. They were classed as “Enterprise”, with a great MTBF – or mean time between failure. This meant they were reliable. They were – at the time I bought them anyway – cheaper than the same sized consumer oriented drives.

Eventually, I realized that I could spend months weighing up the pros and cons of each type, and ultimately it probably wouldn’t matter. Once my new NAS was up and running, then I’d never think about it again. I didn’t want to get hung up on it, so I decided to go with Western Digital Gold drives and not worry about it.

Switched on

Now that I’d chosen a NAS and the drives, all I needed to complete the package was a 10-gig Ethernet switch. But this is where I found it really difficult. In fact this is the part that slowed me down. I spent months looking at 10-gig Ethernet switches.

I liked the idea of link aggregation, especially with an eye to the future. Who can tell what will happen in the next 7 years? Maybe there’ll be a point where I have multiple computers and a mini render farm. I didn’t want to make a short-sighted purchase.

On the other hand, managed switches that support link-aggregation were really expensive – in some cases I’d go through a website product finder and end up being recommended something costing tens of thousands of dollars. Even though 10-gig Ethernet has been around for a long time, it seems like it hasn’t quite entered the consumer market yet.

There were a number of basic, unmanaged 10-gig switches available but they didn’t offer any sort of control. They weren’t super cheap, either. When I bought my gigabit Ethernet switch, my trusty Netgear box had cost less thn $50. But now, even a simple unmanaged 10-gig switch was a few hundred. If I wanted link aggregation, I’d have to pay even more again. But how much was it worth?

Out of the whole process, I found this to be the most difficult decision. I changed my mind every 2nd day. Should I just buy a cheap, basic switch for now and if I need something faster then upgrade in the future? Or should I pay more now and just have everything future-proofed?

I had been idly looking at potential products for months, and I had a page full of scribbled notes. Eventually, I was only able to find 3 managed 10-gig Ethernet switches on the market that cost less than $1,000. One of them wasn’t in stock in Australia, which narrowed it down to two. In some ways, only having two choices makes it easier.

I had been hoping to spend less than $500 on a 10-gig switch. It just seemed like a nice, round number. I spent months checking out 2nd hand options, but nothing suitable came along. Eventually, I decided to stop worrying and just make a purchase. It was now over 4 years since I’d first seen the FS1018 and I needed more storage space, and soon.

I chose an entry-level Qnap managed switch, because I figured as Qnap also make NAS devices then their switches are probably a good fit for my setup. The Qnap M408-4C had good reviews, combined 10-gig ports with existing gigabit Ethernet, and most of all it supported link aggregation. It cost more than I was hoping, but at the same time I was happy to buy something that I wouldn’t have to think about again for many years.

There are many rabbit holes you can fall down on the internet, and when it comes to 10-gig Ethernet, one of them is to do with the types of connectors & cables. Unlike regular Ethernet, which uses rj-45 cables and connectors, there are several different options for 10-gig Ethernet. I started looking into it but eventually gave up. I have better things to do than think about cables and connectors.

The Qnap switch I’d chosen actually supports both types, so I didn’t have to worry about that particular problem.

Push the button

Once I had settled on my shopping list, it was quite nerve wracking to actually push the button and buy everything. I had everything in my shopping cart but couldn’t bring myself to do it. When I took a deep breath and finally clicked through to checkout, so much time had elapsed that my cart had automatically emptied and I had to add everything again.

It had been almost exactly 4 years since I’d seen the FS1018 and decided to budget for a proper NAS. Now I’d settled on a completely different system, after spending months and months reading reviews, articles, and watching YouTube videos.

There were a few delays in getting all the parts together, mainly because I had ordered 8 drives and my vendor only had 2 in stock. But after a few weeks, everything arrived and the floor of my office was covered in boxes.

I was in the middle of a project and knew better than to try and upgrade everything before my delivery deadline. I had waited four years, a few more days wouldn’t make a difference.

Too Easy

Setting everything up was surprisingly – almost disappointingly – easy. I thought that setting it up and swapping everything over might take a day. In the end it took less than an hour. I was surprised that I didn’t even need a screwdriver to install the drives into the NAS – everything clicked into place. The RAM upgrades, SSD cache and 10-gig Ethernet cards were all installed in just a few minutes. It was super easy.

Similarly, unplugging my old Netgear switch and swapping it out for the new Qnap was also completely painless. Having a hybrid switch that accepted standard gigabit Ethernet as well as 10-gig worked well for me, I was able to just plug in my existing cables without any issues, and run the 10-gig cables to the new NAS.

Everything worked exactly as expected once I turned it on, and after setting up the software – thanks to a few YouTube tutorials – I was ready to start copying files. I started with my 6TB NAS, and was once again surprised at how quickly everything copied over. I was thankful I had spent time sorting out a lot of my older files already.

I went though every portable hard drive and USB stick that I owned, and made sure that every file I had was transferred over to the NAS. Until now, my main working drive was the internal 2TB NVMe SSD. It held all of the projects I had worked on over the past few months. I’d copied them to the new NAS, but the next step was to erase the drive and use it as an After Effects cache disk.

More than meets the eye

Only a few years earlier I had thought that having a 20TB NAS would last me for years. But by the time I finished copying everything I already had onto my new NAS, I had already used up about 16TB space. It wasn’t just my working files and career archives. Things like backing up my laptop and setting up time machine, backing up phones, iPads and so on all added to the total. There were older projects that were on drives I’d never consolidated into my main “backups”. Overall, I had a lot more stuff than I thought I did.

In hindsight, I’m glad that I went down the route of having much more capacity thanks to using spinning drives, and not just SSDs. It’s nice to know everything is there, on a system with two-drive redundancy, and reasonably well sorted.

I was surprised at how quickly it took to get everything up and running. The last step was to format my internal NVMe drive and assign it as an After Effects disk cache.

One final mystery

Before I took that last step though, there was time for a benchmark. For years I had been worried that any external drive I used would be slower than my internal SSD. That assumption was the main reason I’d put off buying a proper, redundant NAS for so long. But now it was time to find out for real.

I knew that because I’d installed a SSD cache into the NAS, any regular benchmark wouldn’t reflect real-world After Effects usage. I’d run the AJA benchmark a few times and the results varied, but I seemed to get steady transfer rates of between 600 and 800 megabytes per second. However when copying large batches of files over the transfer rate could occasionally peak over 1000. Overall I’m really happy with the speed of everything, but I still wanted to know how a real-world After Effects project would go.

The last project I completed on my internal drive was a good candidate for benchmarking, as it was typical of the types of projects I regularly do. It was a 4K project that involved lots of layers of 3D rendered assets. The 3D layers were all rendered as EXR sequences.

Starting with the existing project on the internal drive, I cleared out my system – purged caches, etc, and rendered from scratch with nothing else running on my machine. The render time was about 3 hours. Then I purged / cleared everything again and rendered again. The render time was the same, within 15 seconds. It seemed like an accurate result.

Then I cleared and purged everything again and rendered the same project from my new NAS. It rendered in about 2 hours 45 minutes – in other words, about 15 minutes faster, or roughly 10% faster. This was completely unexpected. I had no idea why rendering from the external NAS would be faster than from the internal SSD. I cleared / purged everything and rendered again. Same result, within 15 seconds.

I don’t have an explanation for this mystery, but it’s a nice mystery to have.

Ever since Covid, I have been permanently working from home. It’s important to have a home office and a home setup that’s functional and comfortable. Having a proper NAS means I’m no longer ashamed to look at my desk and its assortment of portable drives. It’s nice to be able to step into my home office to begin work and feel happy and comfortable with my computer.

This was a long personal blog but I’ve been writing articles on After Effects for over 20 years. Check them out here!

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now