5 Things

Distractions, Lists, and Creativity

I crashed my motorcycle on this day, August 10th, 21 years ago. It was both a visceral lesson in the risks of distraction and the beginning of my video career.

It was a warm and cloudless summer day when I headed out with a group of friends for a planned five-day ride through Northern California and Nevada. It was probably my fourth time joining these guys for a multiple-day ride over the past several years.

After a glorious morning start heading north from San Francisco, we stopped in the small town of Willits for lunch before continuing on into the afternoon, taking a smooth quiet road that twisted and carved through hills and valleys for mile upon mile. The endless yellow ribbon stretched in front of us. I was enjoying the steady thrumming of my engine and the floating, flying feeling that only motorcyclists know, coming up out of one curve and throwing my bike into the next one. I had learned by now that my companions were better riders than I, so I didn’t make any attempt to keep up with them.

Besides, I was a little distracted.

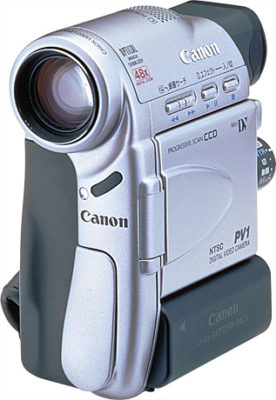

I’d strapped a Canon Elura mini-DV video camera to my leg with about a dozen rubber bands. After experimenting with mounting it to my helmet (on a tiny flexible tripod with lots of duct tape, where the wind would immediately tilt it back to shoot nothing but sky and telephone wires), and to the bike itself (on a metal pole jammed through the rear frame where it would twist to shoot nothing but the side of the road), I found this mounting method reduced vibrations the most, and had an added benefit: by turning my leg I could point the lens in different directions, catching the scenery or my riding companions as we passed each other. I could even turn it off and on while in motion by reaching down with my left hand and pressing the record button, keeping my right hand steady on the throttle. The only hitch? After doing that a few times, I couldn’t remember if the camera was on or off.

With my focus split between the road and my desire to capture our adventure, I came into the next turn – a tight left – too fast. Quickly, it tightened up more: a dreaded decreasing radius turn, nemesis of riders everywhere, made worse by the flat, unbanked surface.

You turn a motorcycle at speed by counter-steering: to turn left, for example, you push on the left handlebar. Intuitively you might think this action would make the bike steer to the right, but gyroscopic and centripetal forces make the bike lean left and therefore turn left. The harder you push, the more the bike leans and the tighter it turns. Push hard enough, and you start scraping parts of the bike on the ground – usually starting with the foot pegs, which have metal bolts attached for this purpose: a kind of early warning signal. To avoid scraping, you can shift your whole body off to the same side, which reduces the amount of lean required.

I had been riding for about 10 years before this moment, including 3 track school classes at Laguna Seca Raceway, so I had a grasp of what to do in this situation.

It was too late to shift my body, so I pushed harder into the left handlebar, forcing myself to look up through the turn and not at the front wheel which was dangerously close to the edge of the pavement. I kept steady on the throttle, fighting the instinct to slow down: if I let up, the bike would pitch forward. So far so good.

Then my left foot-peg dug into the asphalt.

Now, I’ve only leaned my bike over far enough to scrape a peg one other time: at track school, in the back half of Turn Two. That was also a tight left-hand turn, but the track was very wide and I was tight to the inside. At that time, the sudden scraping noise shocked me: I let up pressure on the left handlebar, and the bike skittered to the right a good 5 feet before I recovered and continued through the turn.

On this beautiful California afternoon in the bright sunshine, I didn’t have the luxury of those 5 feet: I was already up against the white line at the edge of the pavement. Once again, the sudden loud scraping noise spooked me and I reacted by relaxing pressure on the left handlebar – just a bit and just for a fraction of a second – but that was all it took for the front wheel to slide off the edge off the road into gravel. It immediately gave way.

I loved riding motorcycles. But I also had a healthy fear of them. In the past decade of riding I had crashed once before. So my first thought as the front tire gave way was this: if I make it through, this will be my last ride.

The rear wheel was still on the road with solid traction, so the back of the bike swung forward around the front. Like a kid flicking a spitball off of a popsicle stick, it shot me off the seat and I lost my grip.

My second thought, as I slid face-down across the gravel, arms out-stretched to break my fall, was the realization that if I had been turning right instead of left, I’d now be sailing off a cliff.

Behind me, my bike righted itself and barreled into the side of the mountain, smashing the plastic cowling, twisting the forks, and contorting the frame.

I came to a rest flat on my belly in a cloud of dirt. It was eerily quiet. My third thought, as I picked myself up and checked all my limbs, was: did my camera survive? And did I get the shot?

Thanks to my helmet, gloves and full leathers, I was unscathed. The rest of our group was well ahead of me, except for John, who almost crashed trying to avoid running into me. He confirmed that I was ok. And that my bike was totaled. Still dazed, I wrestled the camera out from the rubber bands around my leg. Dented, scratched and covered in dirt, I was amazed to find that it turned on. Excited, John and I both bent over the tiny flip out screen as I rewound the tape and pressed play.

Nothing. I had turned it off just before crashing.

That accident taught me to focus. Back home, I used the insurance money to replace my camera instead of my bike, upgrading to a “professional” (at the time) Sony PD-150.

I turned our downstairs storage room into an edit suite, bought Lisa Brenneis’ Final Cut Pro book, Brian Maffit’s After Effects video tapes, and Trish and Chris Meyer’s Creating Motion Graphics tome. I locked myself in that edit suite for the next few months, learning everything I could. I shot every chance I got, and joined the very first Final Cut Pro user’s group in San Francisco.

The connections I made there let to my first book, which let to my second book, to NAB and meeting my creative partner Steve and the start of our 15-years working together at Ripple Training.

The New Distractions

I’m telling you this story because, in the twenty-one years since that day, I’ve noticed a new kind of distraction taking ahold of me. Not as deadly as playing with video cameras while riding motorcycles, and not one that might lead to a new career. It’s stealthy, it’s pernicious, and it’s slowly sapping my productivity and creativity. Maybe yours too.

Video professionals are storytellers at heart. And storytelling is a creative act. As such, it requires both exceptional receptivity and focus: receptivity to new connections and ideas that often appear during those in-between times when your mind is resting, or engaged in a completely different activity; and focus on the execution of our craft, be it writing a script, shooting a scene, or editing a complex sequence.

Now I find that focusing during a shoot is easy: I’m working with other people on a common goal under immediate pressure. But my ability to focus while alone in front of a computer screen has decreased steadily as the channels of communication and the amount of online content have exploded.

Back when I was first learning After Effects, I might have had my email application open, and I’d get perhaps a dozen messages a day. And I had a browser window open to the Creative Cow website, whose forum contributors helped me learn so much (thank you, Ralph Fairweather, RIP).

Today, as I write this, just for text communications I actively use Mail, Messages, Facebook Messenger, Slack, and Telegram. I probably get 200 messages a day. To say nothing of all the compelling and often high-quality educational content on YouTube, and Facebook, and Twitter.

Even with notifications turned off, when my current task gets the slightest bit difficult, I’m just a click away from all of those “urgent but not important” communications. Look, a review about a new camera! Oh, here’s a chat with the editor of Mare of Easttown – I loved that show, maybe I’ll learn something! Oh and I better the check comments on our latest tutorial video, I may need to respond. Hey, I wonder what folks are saying about Final Cut Pro in all those Facebook groups I’m in. Ah, there’s a new message in that Resolve Telegram group!

It might be just 10 seconds here to skim and delete emails or 2 minutes there to read a short article or watch a “how-to” video, but the cumulative effect of these micro-distractions add up. Not only do they steal precious minutes of my day, every time I return to the task at hand, I have to refocus and get myself back in the flow. In fact, according to one study, It takes over 20 minutes to get back “on task.” It’s a slow death by a thousand cuts – or as a friend long ago put it with a less gruesome metaphor: I’m getting bitten to death by ducks.

Are you?

The Five Things

So that brings me to lists. You know, online article or videos titled “the 5 things you really need to know about.” They are everywhere. Why? Because they work. People click on them. I love them. Hey, I’m not getting distracted, this is something I need to know! Just while writing this article, I’ve “learned”:

- 10 Tips for Shooting Cinematic Smartphone Videos

- 7 Lighting Tips

- The Top 8 Seamless Transitions

- 5 Great Weekend Reads

- The 7 Worst Habits for your Brain

- The 6 Concepts You Should Know to Be Financially Literate

- My Top 7 Features of DaVinci Resolve 17 for Craft Editors (by our very own Scott Simmons here on PVC)

(I didn’t provide links for them all since I’m distracting you enough already!)

Did you click the link for this article planning to skim through it, quickly locate the headings for each of the “5 things”, and then mentally check them off with a satisfying “oh yes, I already knew that”? Or maybe you’ll discover something new that you promptly forget because you didn’t immediately put it into practice? I know that’s what I do. So, am really I learning something – or am I just distracting myself?

For me, I think it boils down to two kinds of distraction: the kind that I use to avoid hard work, and the kind that can refresh me, really improve my skills, give me new ideas and renew my focus.

I don’t know how to help you with the first kind – as you can see, I’m struggling myself. But here are five practices that I believe fall in the second category: “distractions” that help me with my creativity. I try to do them every day. I usually fail. But I believe they can open us up to more sources of inspiration, greater creativity, and a better ability to focus on doing excellent work.

Thing 1: Read a book.

I mean read a physical, tree-killing book that sits on your nightstand and reminds you to read it. Make it something you know nothing about. Read it in a comfy chair – away from the computer. Even for 5 minutes at lunch instead of scrolling. You’ll enjoy it, and you’ll get inspired in a way you didn’t expect. Visiting family back east a few weeks ago, I came across Steven King’s On Writing in a local bookshop, bought it, and devoured it. However in my daily home work routine, I find it much more difficult to do this. I have a stack of books by my bed, but if I’m lucky I manage a couple of pages before turning in.

Thing 2: Write. Or meditate. Or both.

Some folks don’t like to write; some can’t sit still. I’m betting you can do one or the other. A daily writing routine – even simply journaling 10 minutes of stream-of-consciousness – can clear out mental debris and help clarify your thinking. Check out The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron. I try to write for a least a few minutes every morning. I don’t always succeed.

A regular meditation practice can have the same results. I’ve been practicing for over 30 years. These days it’s just a few minutes on the cushion right after I first wake up, but it’s enough to make me feel more present, less lost in thought – and I ofter get some really good ideas in those few minutes. Check out Sam Harris’ Waking Up app .

Thing 3: Exercise.

Some people love it; some hate it. It works for me. Get outside every day at least for a short walk. I’ve been doing yoga for almost 20 years now and it has changed my life. But somedays my morning dog walk is all I get in. The rest of the day flies by and suddenly it’s getting dark and I didn’t leave my office – but I’m glad I saw the sun and the hills for a few moments in the morning.

Thing 4: Play an instrument. Or draw. Or paint.

Develop a creative outlet apart from your work. I started playing guitar a little over 10 years ago. I practice almost every day, even if it’s just a few minutes before going to bed. I’ll never be great. But I love it, and it’s an excellent mental workout.

Thing 5: Practice your craft.

If you shoot for a living, do a personal project. If you are are editor, cut something something new – a comedy, or a fight scene. Do something small every day.

And here’s the thing: don’t just read or watch tutorials to improve your craft. Put what you learn into practice as soon as possible. I know that’s easier with a quick editing tip than learning to shoot green screen, but you get the idea. I watch plenty of YouTube videos to improve my skills, but then I promptly forget what I learned because I don’t practice it right away.

If you aren’t going to practice it soon after watching, just skip the tutorial and do something creative instead. Note this advice is coming from someone who produces tutorials for a living! At Ripple Training, we provide projects and media for almost all our tutorials, but I’ll bet dollars to donuts that most people sit back and watch them without practicing as they go. I get it.

I realize that reading, writing, meditating, exercising, jamming and practicing a work skill every day may seem absurd in the face of a mountain of work and looming deadlines. I sure don’t do them all every day, but I like having the goal – and I don’t kick myself when I fall short. Often I’ll slip them in at the very beginning and very end of the day, because once I’m working, forget about it.

You’ll notice I didn’t include advice about “limiting social media” or turning off distracting apps. Those are probably good ideas but I just don’t do them myself. It’s a problem. I get a little dopamine hit with every new email, Facebook notification, or Youtube comment. Oh wait here’s a video about Wes Anderson’s style – I need to go watch that (it’s great by the way).

Are you doing any better than I am with all these distractions? Leave a comment. Oh, and if you have any favorite lists, link please!