The US$8320 (street price) Sony PMW-EX3 is an eight-pound, high-definition “chainsaw” camcorder with three 1/2″ CMOS sensors. It’s essentially a repackaged EX1—true 1920×1080 sensors, 1080 and 720-line XDCAM EX recording on SxS cards, variable frame rates, wide-latitude cine gammas, hugely tweakable—with an interchangeable lens mount, an impressive EVF, and improved ergonomics. Like the EX1, it makes stunning HD images, and like the EX1, it’s a handheld handful.

The $6500 PMW-EX1 shipped in late 2007, and immediately raised the bar for image quality in affordable HD camcorders, even as it pushed the limits of handholdability past many people’s breaking point. Less than a year later, Sony has offered up the EX3: the same guts in a new, more flexible, and more ergonomic package. The EX3 debuted at NAB 2008 at a suggested MSRP of “under $13,000”, and indeed so it turned out to be: $9990 list. The resulting $8320 street price, only $1800 more than the EX’s, made a lot of prospective EX3 purchasers very happy—and annoyed many folks who had just bought EX1s. EX1 owners needn’t feel bad: the EX3 expands the EX lineup, but doesn’t replace the EX1, which remains available as a smaller, lighter, 20% less expensive alternative with the same image quality.

Sony kindly lent me an EX3, and I set it up side-by-side with the EX1 we purchased earlier this year for a close comparison. As a result, and because the EX1 has been so thoroughly dissected already, I’m going to focus this review on the differences between the EX3 and the EX1. I’ll then cover the camcorder in a more normal manner, with multiple references to the EX1 review—if you’re already familiar with the EX1, you can skip those links and go straight to the conclusion.

What’s New

Sony’s First Chainsaw

The EX3 looks like the results of an unholy assignation between an EX1 and a Canon XL H1.

The Sony PMW-EX3.

The lens, surface treatments, and user interface are all clearly descended from the EX1, but the upswept “chainsaw” body, large EVF, lens interchangeability, and weight (the XL H1 is 8.3 pounds) echo Canon’s camera. While the Canon with its 20x lens is almost three inches longer than the EX3, the EX3 is slightly wider, and their weights are comparable. Indeed, the XL H1 series aside, the EX3 is the biggest and heaviest non-shoulder-mounted camcorder around.

PMW-EX3, PMW-EX1, HVR-Z1, and Panasonic HVX200 side by side.

It may not look so different from the top, at least lengthwise, because handycam-style cameras usually have EVFs projecting aft of their bodies, but the side view makes the height and length of the EX3 clear:

PMW-EX1 in front, PMW-EX3 behind.

The EX3 towers over the EX1 and is considerably bulkier. While neither one is huge by the standards of shoulder-mount cameras, the EX3 is pushing the limits of what you can comfortably stuff into an airline carry-on and still have usable room for anything else. While the EVF’s eyepiece tube can be removed, the rest of the EVF remains sticking out the side of the camera, so it can’t really be packed flat.

If you attach the supplied cheek pad and pull the shoulder brace out to its full extent, you get the following package:

EVF tilted up, shoulder pad extended, cheek pad attached and locked in place.

Handholding the Chainsaw

The biggest operational issue with the earlier, Handycam-style EX1 is the challenge of handholding it: it’s heavy, and its off-center grip is so smoothly rounded and untextured that it’s nearly impossible to hold the camera level with the right hand alone. The EX3’s chainsaw form factor lets you brace the the camera against your body, adding another point of support and stability. The EX3 has a squishy shoulder pad nestled beneath its upswept back end, with a cylindrical, padded bolster at the back. You can press in a latch at the base of the camera and pull this pad out about an inch and a half, as shown above. When combined with about three inches of front-and-back adjustability in the EVF, this lets you tweak the camera’s position to fit your shoulder in a number of ways: you can let the pad ride up, as Nigel Cooper does, or you can butt the bolster hard up against your shoulder, albeit with the camera a bit lower down.

Bracing the camera against you this way definitely helps, making it easier to grab stable shots without benefit of tripods or other supports. But the camera is still quite side-heavy; without the left hand under the lens, the EX3 wants to dive to the left. The EX3’s handgrip is the same as the EX1’s: it’s just as smooth and untextured, and just as far off-center, and the bulk of the EVF makes the camera even more laterally unbalanced than the EX1. Considering the added mass (the EX3 is 30% heaver compared to the EX1), the EX3 is still a handful to handhold: it’s inherently more stable, but for shots longer than a few seconds, it winds up being equally stressful.

But we’re not done yet. At NAB, Sony was “experimenting with” a bolt-on cheek pad, and the cheek pad wound up shipping with the EX3. It’s a bracket that attaches both at the base of the top handle and between the shoulder pad and the body, with a large plastic “flag” that rests against the side of the face. It uses a spring-loaded cam system to keep it in place: slide the flag up along its bracket, and it can be swiveled away from the camera, or inwards 45 or 90 degrees, both of which have latching positions.

The cheek pad in its normal position rests solidly against your face, so the camera is constrained from diving off to the left. You can safely remove your left hand from the lens to go fiddle with controls without the camera immediately departing from controlled flight.

Swung outward, the pad lets you gain purchase on the many BNCs on the back end of the camera; swiveled in 45 degrees it’s out of the way, but still allows attached cables to pass or an oversized BP-U60 battery pack to remain installed; swiveled in 90 degrees, it sits flush with the back side of the camera (even with the stock BP-U30 battery installed), assuming you don’t leave any cables plugged in.

The cheek pad can be opened outward to allow easy cable access.

The locking cam is a small plastic tab at the base of the flag; it’s one of the three components on this camera that I worry about breaking in normal use. It just doesn’t seem robust enough to deal with normal stresses as well as the occasional unintentional rough twist. Having said that, I didn’t try to force it, and it may be perfectly fine; it just seems uncharacteristically flimsy given the build quality of the rest of the camera.

Attaching or removing the cheek pad requires three different sizes of screwdriver, and the swapping in (or out) of a long screw in place of a short screw, so it’s not something you’ll do on the spur of the moment.

Overall, I’d rate the camera better than the EX1 for stable handheld shooting, but it’s still not something I’d like to use without secondary support. No one operating either the EX1 or the EX3 will ever mistake it for an HVR-Z7 or HPX170.

Adding a support like the DvRig Junior makes the EX1 far more user-friendly—I shot a Direct Action Cinema feature with the EX1 on a DvRig Junior and found the combo very pleasing—and it works just as well on the EX3. Doubtless other monopods, belt pods, shoulder braces and suspension rigs work their magic as well; when something other than your own wrist is carrying the weight, both EX-series machines transform from heavy handfuls to smoothly controllable camcorders.

(To be fair, though, some folks handhold Canon XL-series cameras all day long and don’t complain. I’m curious about Bruce Johnson’s take on the EX3, as he’s a long-time Canon user.)

The EX3’s EVF

The EX1 has one of the best LCDs around, but its EVF isn’t anything special. The EX3 takes the EX1’s LCD and makes it the EVF: the LCD is wrapped in a proper hood, mounted on a rigid, repositionable arm, and equipped with a long eyepiece tube and a large eyepiece lens.

The EX3’s EVF, with controls across its front.

The 3.5″ LCD at the base of the EVF is the same one used on the EX1; it resolves about 500 TVl/ph horizontally and 400 vertically. The eyepiece allows easy viewing even with glasses, and its magnification is substantial. Even without the Expanded Focus pushbutton on the handgrip, which enlarges the image by 2x, the EVF is quite usable for HD focusing: its image is huge. It’s about 20% larger than the image seen in the EVFs on the EX1 and the HVR-Z1, and about 40% larger than the image in an HVX200’s EVF. Indeed, I had to go back thirteen years to find a comparably large viewfinder image: I literally blew the dust off my venerable DCR-VX1000, one of the first-generation DV camcorders, and powered it up to compare it. The EX3’s image is slightly wider, but not quite as tall (the EX3 is of course a 16×9 machine, while the VX1000 makes a 4×3 picture).

This is what an EVF should be: big enough and sharp enough to see detail, not so small you think you’re looking down a dark tunnel at a distant image.

Furthermore, the EX3 is the first small camera I’ve seen with an LCD EVF that has a real, honest-to-goodness peaking control.

No peaking.

Maximum peaking (note its effect on the data displays).

The front of the EVF has rotary knobs to vary the EVF’s brightness, contrast, and peaking, so you can dial in just as much (or just as little) as you’d like.

As it’s a peaking signal applied by the EVF itself, even the data displays wind up with extra edging. It can make them a bit harder to read, but (for me at least) that’s a small price to pay for a real peaking control. The camera’s menus let you choose between High and Normal peaking frequencies.

If you prefer, the “digital peaking” as used on the EX1 and Sony’s HDV cameras is still available through the menus: select “color” instead of “normal”, and choose white, red, yellow, or blue edging. Now the rotary control dials in the colored peaking at the four fixed levels of off, low, mid, and high, just as the menus do on the EX1. As this peaking happens “in the camera” instead of “in the EVF”, digital peaking doesn’t affect the overlaid data displays.

The EVF is affixed to the camera on a dogleg arm, secured to the camera’s top handle with a locking lever beneath it. It offers one inch of lateral adjustment and three inches of back-and-forth adjustment, the latter through a 90 degree pivoting range for the mounting arm (45 degrees forwards to 45 degrees backwards). Combined with the pivoting range of the EVF itself, you can position the EVF at any angle around a complete 360 degree circle. However, you cannot retract the EVF under the handgrip, nor can you aim it sideways.

The EX3 uses a sliding, rotating EVF mount.

That lateral 1 inch adjustment is rather less than the normal interocular distance of about 2.25 inches. If you have the cheek pad mounted, a left-eyed person extending the EVF leftwards as much as possible will find it hits him (or her) smack on the bridge of his (or her) nose. However, lefty viewers are readily accommodated by removing the cheek pad and snuggling closer to the camera.

The EVF’s eyepiece tube attaches at two points: a snap-in pivot at the top, and a latch at the bottom. You can unlatch the tube and flip it up, or depress a small catch and slide the upper pivot out of its mounting to remove the tube entirely. That pivoting mechanism is the second part of the camera I worry about breaking; it’s a tiny little thing, and the EVF tube is a long lever arm, easily whacked. Perhaps the pivot is made of black-painted adamantium, but I worry about it nonetheless.

The EVF includes a Mirror Image switch to reverse the image for viewing from the front, since the double-jointed EVF mount precludes the usual flip-over switch inside the LCD’s pivot. The Display / Battery Info switch is here, too, as is the zebra button.

In summary, the EX3 has a real viewfinder: a big, fat, crisp, focus-worthy, color one, closer to the EVF on the $100,000 F23 than to anything on a Handycam.

It’s what a modern EVF should be.

Dang, it’s nice.

Changing the Lens

The EX3 uses the same superb Fujinon glass as the EX1, but in Sony’s new, interchangeable-lens EX mount:

The EX3’s lens attaches with a mount as big as the camera is.

The EX3’s stock 14x lens, all by itself.

The handgrip comes away with the lens, so replacement lenses need their own handgrips. As most 1/2″ and 2/3″ lenses have their own grips, this is fine.

The EX mount is both wide and flat; it’s an excellent design:

- The large diameter resists torque better than smaller-diameter mounts, so the flanges and breech lock can be thinner and lighter than on smaller-diameter mounts, yet still support the weight of a big lens. By the same token, the wide-diameter mount provides a very rigid connection between camcorder and lens.

- The mount is both thin and close to the front of the chip block; adapters for other lens mounts are easily fitted, making the EX mount as close to a universal mount adapter as can be found.

- There’s plenty of room for electrical contacts between the lens and the camera, or between a different mount adapter and the camera.

The EX3 comes with an adapter for standard Sony 1/2″ mount lenses, which neatly drops into the EX mount, letting you use existing 1/2″ lenses like those used on PDW-series XDCAM camcorders. Sony warns that only hot-shoe lenses communicate with the camera (there is no separate lens data port for cabled lenses), and that not all lens functions may work, depending on the lens.

The EX3 naked, and with its 1/2″ lens mount adapter.

Sony offers optional adapters for 2/3″ B4-mount lenses and for Sony Alpha-series DSLR lenses. I wouldn’t be the least bit surprised if third parties developed EX-mount adapters for Canon and Nikon SLR lenses, and I expect the various 35mm relay-lens adapter folks (P+S Technik, Redrock Micro, and the like) are looking into EX-native adapters (of course, you could also get the EX-to-B4 adapter and use existing relay-lens systems).

As to EX-native lenses, Sony has announced a Fujinon 8x wide-angle zoom with a 4mm wide end, but I don’t know of any that have escaped from the labs yet.

The stock 5.8-81.2mm zoom lens has the same 77mm front threading and the same bayonet system as its EX1 counterpart, so current EX1 lens adapters, such as Sony’s $450 VCL-EX0877 0.8x wide-angle adapter, will also work on the EX3. That Sony adapter gets you to 4.6mm, or roughly what a 16mm will do for you on a RED ONE or a 35mm mopix camera. (Mind you, the 1/2″ Fujinon XS13x3.3BRM goes as wide as 3.3mm, and it fits on the EX3 using the supplied mount adapter. Mind you, that’s a $13,000 hunk of glass!)

Control Improvements

- Controls that reside on the EX1’s rear panel have been moved to the left side of the EX3, consolidating and rationalizing them in the process. It’s easier to find controls by feel, and to use them without moving your eye from the EVF.

- The impossible-to-feel membrane switches on the EX1 are gone, replaced by actual buttons on the top panel and elsewhere.

- Steadyshot now has a dedicated button on the lens barrel, instead of being buried in the menus.

- Slow & Quick Motion (variable frame rates) has a dedicated dial on the camera body, instead of being buried in the menus.

- EVF brightness, contrast, and peaking have dedicated rotary controls.

- A clear plastic door protects audio level controls from inadvertent adjustments.

Connector Changes, etc.

- The multipin composite / S-Video / audio-out plug on the EX1 is gone, replaced by a proper BNC (analog composite video), a 4-pin Y/C jack (S-Video), and dual RCAs (audio out).

- The EX3 adds BNCs for timecode out, timecode in, and genlock.

- The EX3 has a multipin port for connecting a paintbox: either the RM-B150 or RM-B750 Remote Control Units.

- The EX3 uses the same mini-D connector for component analog out as other small Sonys, and the usual mini-B USB jack, but these have been moved aft of the handgrip and no longer interfere with holding the camera.

- The EX3 supports 23.98PsF output, in E-E mode but not in playback. (EX1s being shipped now also have this capability, and Sony will be offering a firmware upgrade option for existing EX1s to enable it.)

- Unlike the EX1, the EX3 doesn’t drain its battery when it’s shut off.

- Unlike the EX1, the composite and Y/C outputs remain active when component and HD-SDI outputs are enabled. HD-SDI and i.Link are mutually exclusive, but that’s the only limit on mixing ‘n’ matching simultaneous outputs—very handy when you need send different feeds to offboard recorders, the director’s monitor, and the like.

Next: Design and Handling…

Design and Handling

The EX3 is a big, heavy camcorder for a handheld. It’s about eight pounds with battery and SxS cards loaded, and with shoulder pad and EVF in their unextended positions the camera is nearly 17 inches long, 9 inches wide, and 8.5 inches tall.

The EVF’s bulk makes the camera side-heavy. It’s stable on a hard surface, but set the EX3 down upright on a car seat or other soft surface and it’ll gently topple over to the left.

Lens

The Fujinon 14x 5.8-81.2mm zoom is fronted with a bayonet-mount lens hood with flip-open shutters, so there’s no lens cap to lose. Filters attach using 77mm threads.

The EX3’s 14x Fujinon lens.

The rubberized focus ring can be used for full manual control, or servo focusing. Pushed backwards (“Full MF”), it engages a calibrated focusing scale with hard stops, allowing positional repeatability like a fully manual lens. Pushed forwards (“AF/MF”), it works like any other servo lens, allowing manual and automatic focusing, albeit without hard stops in manual mode.

Macro focusing works in the pushed-forward, AF/MF mode only. Normal near-focus limit is just over 2.5 feet from the front of the lens; in macro mode, that minimum distance decreases to about an inch from the lens at full wide angle.

The focusing scale is recessed behind a window, which make it hard to see from the normal operating position behind the EVF.

A fully mechanical zoom ring takes 90 degrees to traverse the zoom range. It’s well-damped and has an excellent feel. Sliding a switch under the lens engages the lens’s zoom motor, with a conventional variable-speed rocker. Slow power zooms take 30 seconds or longer; fast ones are over in two seconds.

Aft of the zoom ring, three slide switches toggle the iris control between auto and manual, enable macro focusing (in AF/MF mode only), and switch AF/MF focusing between automatic and manual. A pushbutton above toggles Steadyshot (which works as well as any Sony optical Steadyshot does: very well), while one below is the PUSH AF momentary autofocus button.

A proper, calibrated iris ring sits aft of the switch bank. It gives you full, stepless control over lens aperture.

The lens then travels straight back into the EX mount. The breech lock ring for the EX mount is roughly the same diameter as the zoom ring, and has a similar, stubby lever on it, in roughly the same angular position as the zoom lever with the lens at mid-telephoto.

On a couple of occasions I found myself trying to zoom with the breech lock; this isn’t recommended if you like keeping the lens attached to the camera. Fortunately the breech lock requires quite a bit more torque than the zoom ring does, so I always caught myself before re-enacting the famous Apollo IV footage of the Saturn V first stage separation! Still, this is something to be aware of; don’t just blindly grope for the zoom lever and give it an enthusiastic twist.

The lens grip is attached to the right side of the lens and can be rotated forward through more than 90 degrees, from flat and level to slightly past vertical, the latter position being useful for low-mode shooting. The grip is smoothly rounded and does not afford much in the way of lateral rotational resistance, so it doesn’t provide much kinesthetic feedback about the camera’s tilt, nor much purchase to prevent same. On the back it has a start/stop pushbutton in a sealed rubber cover; on the top, behind the zoom rocker, it has pushbuttons for Expanded Focus (which magnifies the EVF image 2x for easier focusing) and Rec Review.

Note that it’s easy to push Rec Review instead of Expanded Focus (when the camera is stopped, that is; Sony sensibly disables Rec Review when you’re recording), and if you have Rec Review set to play back the entire previous clip, you may wind up sitting there for a long time while the previous clip plays back (I found this out the hard way on the EX1; playing back the entire clip seemed like a good idea at the time…). You can also set playback to the most recent 3 or 10 seconds, both of which are less troublesome if invoked accidentally.

Camera

The front of the camera’s baseplate has recessed buttons for white balance and Assign 4 (user-definable) and a slide switch to turn the shutter on or off. They are flush-mounted and tend to be hard to find by feel.

Front buttons, and the zoom motor slide switch.

On the left side of the base, similar pushbuttons bring up status displays, the main menus, and the picture profiles; these are easier to find, perhaps because you can see them from the corner of your eye while operating the camera. There’s also a thumbwheel for navigating menus and setting parameters; it pushes in to confirm a setting or dive deeper into a menu. The Cancel button beside it backs out of a choice or a submenu.

Having these related controls all in a row, instead of being spread across the side and back of the EX1, makes it a lot faster to set up the EX3.

The left side of the EX3 in full-auto mode with S&Q Motion enabled.

A three-position slide switch chooses between camera, power-off, and media playback modes. The switch is just as finicky as the one on the EX1, and it’s far too easy to overshoot the power-off position by accident. Normally, it takes the camera five seconds to illuminate the EVF when you turn it on, but changing between camera and media modes causes the EVF to go dark for nine seconds. During these nine seconds, you’re easily fooled into thinking you’ve powered the camera off as you’ve intended, when really you’ve simply changed operating modes. Walk away for a nice dinner and you’ll come back to a dead battery.

The side of the camera has three assignable buttons, with sensible default settings, a two-position ND filter (3 and 6 stops of ND), three-position chromed toggles for gain and white balance, a pushbutton for colorbars, an illuminated full-auto pushbutton, and the Frame dial.

The Frame dial selects frame rate in S&Q Motion (Slow & Quick Motion, a.k.a. variable-frame-rate recording: overcranking and undercranking). Push it in for a second, and a blue ring around it lights up to indicate that S&Q Motion is enabled. You can then dial in the frame rate you want, anything from 1-30fps in 1080p or 1-60fps in 720p (changing frame rate cannot be done while the camera is recording, only when it’s stopped). Push and hold the dial again to turn the lamp off and return to normal, realtime recording.

Atop the body reside buttons to control Shot Transition: basically a two-position shotbox with presets for zoom, focus, exposure, and other parameters. You can set up two presets for immediate recall, or program a timed transition between them. It’s a bit fiddly to set up, but gives you smoothly-repeatable control that’s very handy at times.

There’s also a button to toggle the EVF’s counter display between timecode, user bits, and a simple duration counter.

SxS door and audio guard opened.

The storage section of the camera sweeps up, giving the camera its chainsaw appearance. Two SxS memory cards load behind a flimsy flip-open door (the third part of this camera I worry about breaking; the EX1 has such an elegant sliding door that it was a shock to see the floppy, double-hinged door on the EX3). A small notch above card slot #2 allows passage of the optional PHU-60K hard disk’s cable: it connects directly into an SxS slot and looks like a 60 GB SxS card as far as the camera is concerned (P2 users will be reminded of the similar, much-lamented CinePorter, which never came to market). A slot select button lets you toggle the active SxS card.

Two audio level controls reside behind a flip-open plastic guard, and channel-specific switches let you choose between the internal two-channel microphone and the dual XLRs, and between auto and manual level control.

Rear Panel

The rear of the camera has BNCs for HD-SDI out, timecode in and out, and genlock in. There’s a four-pin i.Link (FireWire) port for HDV-compatible 1394 data (SQ recording modes only). There’s also a connector for hooking up the RM-B150 or RM-B750 Remote Control Units: studio-style paintboxes allowing remote control of menus, exposure, and the like. All connectors have individual, tethered rubber caps.

The EX3 as seen from behind.

The HD-SDI output is a full, 10-bit signal with embedded audio and timecode. The genlock input accepts either SD or HD reference signals.

The supplied BP-U30 battery fits flush within its compartment, and lasts for about two hours. If you opt for a BP-U60 battery instead, it’ll stick out, but will run the camera for four hours. Remaining battery time is shown in the EVF.

Testing the battery’s charge while it’s installed in the EX3. You can also check its runtime using the camera’s “Batt Info” button.

Right Side

The right side of the camera has a 1/8″ stereo headphone jack at the base of the top handle, a DC IN connector for the AC Adapter / battery charger (which won’t charge the battery while it’s on the camera), a BNC for composite video, a 4-pin Y/C connector for S-Video (hooray!), RCAs for audio output, a mini-D-shell component video port, and a mini-B USB port. All these port are far enough back that they don’t interfere with your hand or wrist when handholding the camera.

Right-side connectors on the EX3.

Etc.

The EX3’s top handle is very similar to the EX1’s, save for the EVF mount: a stereo mic pair sits at the front, topped with a passive shoe mount and followed with a small panel of playback and menu-navigation controls, including a four-way joystick that serves as an alternative to the side-mounted thumbwheel (the joystick is quicker to navigate with most of the time, while the thumbwheel is handy for traversing the +/-100 value ranges of many setup parameters). A top-mounted start/stop trigger with locking lever, a simple forward/off/reverse zoom rocker with programmable (but not variable) speeds, and a second accessory shoe at the back finish off the top controls.

Dual XLRs hang off the right side of the top handle, with slide switches for line/mic level selection and +48v phantom power.

The camera comes with a small IR remote control, one BP-U30 battery, battery charger / AC adaptor, shoulder strap, component video cable, USB cable, cheek pad, and 1/2″ lens mount adapter.

Next: Menus, Settings, Performance, Features, Conclusion, & Links

Menus and Settings

The EX3’s menus and settings are identical to the EX1’s menus and settings with only a few exceptions:

- Camera Menu

- Auto Blk Balance: lets you manually trigger a black balance calibration (on the EX1, this is in a hidden maintenance menu).

- Shutter: a few additional speeds, such as 1/120 in 24p modes.

- S&Q Motion: grayed out, since it’s handled using the Frame dial.

- No Steady Shot: it has its own dedicated lens button.

- VF SET (instead of LCD/EVF SET)

- No separate LCD and EVF menus.

- Peaking: Normal, or Color (as described earlier in the EVF section).

- LENS (mostly hidden in maintenance menus on EX1)

- Auto FB Adjust: adjust backfocus.

- File: recall or save a lens compensation file (two presets for EX lenses, plus four user files).

- Flare: set R, G, and B flare compensation for a lens.

- Shading: full per-channel shading controls for H and V sawtooth and parabolic corrections.

- OTHERS

- Genlock: set horizontal phase and lines of advance; set 1080/24p E-E output as either 60i with 2:3 pulldown or as 24PsF (actually 23.98PsF).

Performance

I was initially surprised to find that the EX3 processed images differently from the EX1 despite the same settings: gammas, clip points, and color rendition were all quite different. After some puzzlement, I tried resetting the EX3, whereupon it started behaving exactly like the EX1 in every comparable respect.

That initial discrepancy highlights the software-driven nature of the EX cameras. It’s not uncommon for our production-model EX1 to respond to a perfectly innocuous switch flip, say, to change gain, with no response other than a message in the display: “Cannot Proceed”. Likewise, the loaner EX3 became cranky on several occasions; it decided to be Bartleby, the Scrivener instead of performing perfectly reasonable operations. [1] (Sony tells me that my loaner was a pre-production unit, so release cameras may be less cranky; still, it’s never a bad idea to back up your presets.)

On some occasions, simply shutting the camera off and restarting it clears its recalcitrance; other times, one has to use Menus > Others > All Reset to regain the camera’s co-operation. In those cases, all parameters, including the picture presets, are reset to factory settings, so it’s wise to make sure you’ve saved your settings onto one or more SxS cards.

I didn’t notice any back-focus issues with the EX3, nor did I see any vignetting from Steady Shot during violent camera moves, but aside from that the lens performed the same as the one on the EX1.

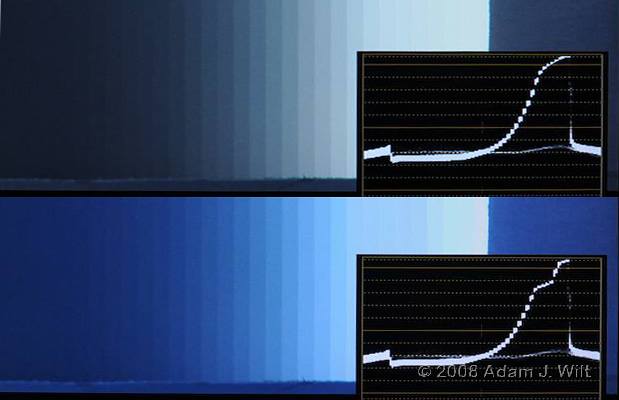

I mentioned in the EX1 review that I wasn’t happy with some of the highlight handling on the EX1 when standard gammas are used. The EX3 behaves the same way, and I’ve isolated the problem: the standard-gamma knees work properly for uncolored highlights, but when a highlight has a strong chroma component, the knee shuts off prematurely, allowing colored highlights to suddenly blow out.

EX1 step-wedge images and their waveforms, photographed on a Panasonic BT-LH1700W monitor using the built-in WFM. Above: white highlights. Below: colored highlights. The EX3 behaves the same way.

The degree of this blowout depends on the saturation of the highlight, and it only happens in standard gammas. I have been able to reduce it somewhat by changing the knee point and slope parameters, but I haven’t been able to eliminate it (Sony’s Juan Martinez suggests lowering the gamma setting. On our EX1 with 1.03 firmware, this has no effect on color highlight blowout; it may on an EX3 or an EX1 with newer firmware, but I had already returned the EX3, so I can’t validate this).

The degree to which it bothers you is, of course, up to you.

Cine gammas are not affected by the problem.

Special Features

I’ve already covered genlock, 23.98 PsF output, the Frame dial, the EVF, and the removable lens. Everything else on the EX3 tracks the EX1’s special features.

Conclusion

The EX1 set a new standard in low-cost cameras for raw resolution, latitude, and frame-rate flexibility (it also set a new standard for awkward handholding—but then, we must suffer for our art).

The EX3 reworks the EX1 into the chainsaw form factor, with an interchangeable lens, a best-of-breed EVF, and numerous ergonomic improvements that make operation faster and more fumble-free. While it’s still too much of a handful to handhold for long periods, the design helps stabilize the camera, allowing steadier shots.

The EX1 is 20% cheaper, 30% lighter, and easier to pack in a carry-on bag. If you’re happy with a fixed lens (and a mighty good one at that) and with the EX1’s sterling LCD and so-so EVF, and you can use some form of camera support to carry the camera’s weight, it’ll do everything you need as well as an EX3 will.

But if you want the flexibility of removable lenses, the joy of the best EVF in its class, an improved control layout, and/or need to handhold steadily without any additional support, the EX3 is worth the extra cash. It raises the bar once again.

Pros

- Highest resolution and detail in its class, with minimal aliasing.

- 1-30fps 1080p, 1-60fps 720p, directly accessible using Frame dial; 1080i; 50Hz and 60Hz operation.

- Interchangeable lens with clever EX mount.

- Crisp 14x zoom with no chromatic aberration at most focal lengths.

- Standard 1/2″ lens mount adapter supplied.

- Excellent tonal scale control with wide latitude.

- Cine gammas have superb highlight handling.

- True 1920×1080 sensors, true 1920×1080 and 1280×720 recording (XDCAM EX HQ).

- 1440×1080, 25Mbit/sec HDV-compatible mode (XDCAM EX SP) with i.Link I/O.

- Linear Matrix for fine color control.

- Robust SxS solid-state recording; lightning-fast offloading.

- True manual iris and zoom; indexed manual focus with lens scale.

- Best EVF in its class; great status displays; real peaking.

- 10-bit SDI with embedded timecode and audio; 23.98PsF capable.

Cons

- Awkward to handhold (better than EX1, but still a handful).

- “Clock radio”-style power switch makes it easy to switch camera on by mistake.

- Standard gamma knee doesn’t handle colored highlights properly.

- “Mustache” distortion at wide angles.

- No SD (480- or 576-line) recording. SD outputs lack proper downconversion filtering.

- No single-frame or slo-mo playback.

Cautions

- CMOS rolling shutter.

- 25 Mbit/sec XDCAM EX SP shows artifacts in fast-changing scenes, like HDV; this is less of a problem in 35 Mbit/sec HQ.

- No on-board tape to hand the client at the end of the day.

- Don’t mistake the lens mount lever for the zoom lever.

Links

Sony’s EX System Brochure covering the EX1, EX3 and EX30 desktop recorder/player.

Philip Bloom’s video overview on YouTube

Nigel Cooper’s EX3 review

[1] For those unfamiliar with the story, Bartleby is a mild-mannered fellow who, at arbitrary times, responds to any request with a quiet and unassailable, “I would prefer not to.”

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now