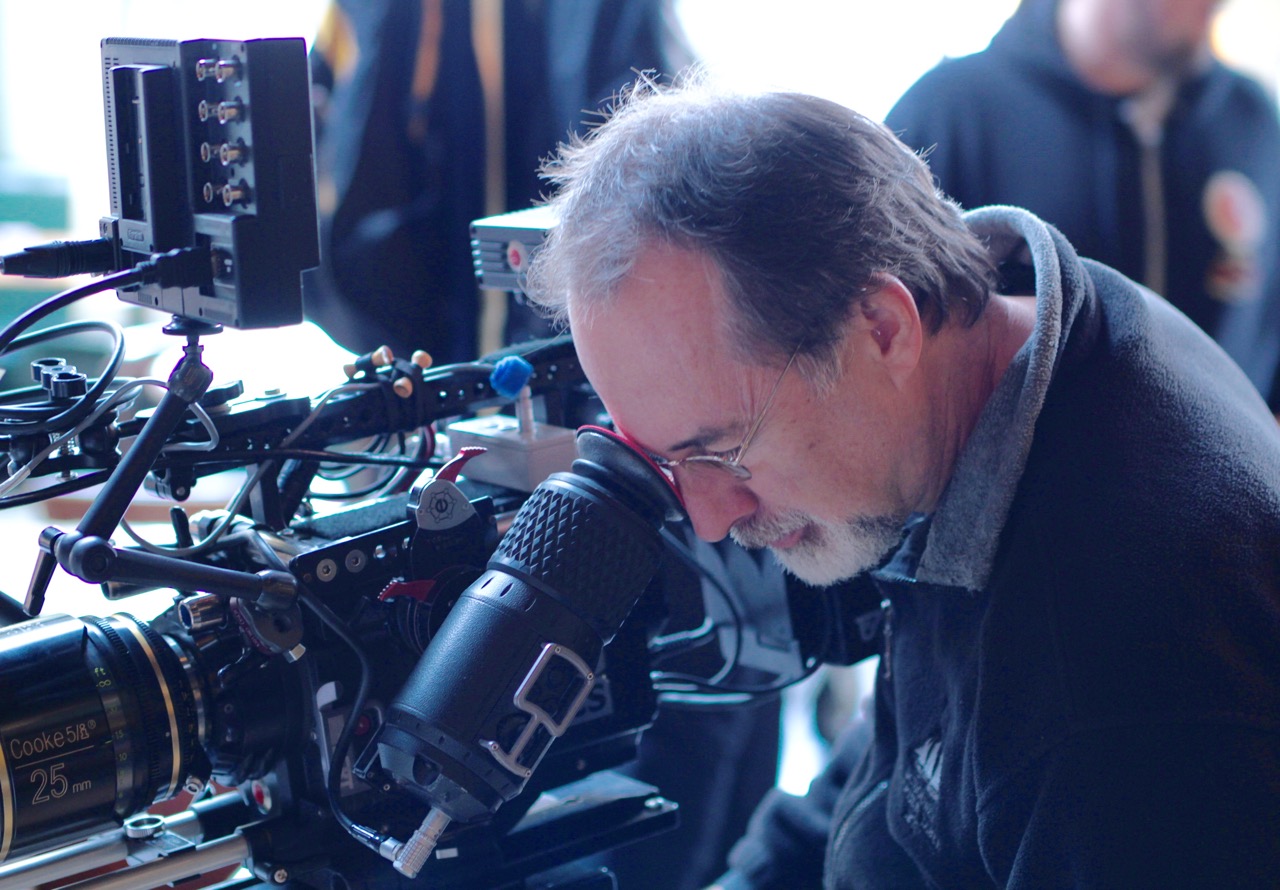

Paul is originally from Kalamazoo Michigan and now resides in Port Washington, NY with his wife Deb. Paul is primarily known for his work with comedian Louis CK, but has also shot features, documentaries and series-based shows such as the Hulu comedy, “Deadbeat”. Paul will be taking part in a panel discussion for the upcoming Manhattan Edit Workshop event September 30th, 2015 along side other cinematographers such as Nancy Schreiber, ASC (November, The Nines, The Comeback) Matt Porwoll (Cartel Land, Crisis Hotline: Veterans Press 1), Jerry Ricciotti (Vice, Vice News), and Bob Richman (An Inconvenient Truth, The September Issue, Paradise Lost: the Robin Hood Hills Child Murders).

Paul is originally from Kalamazoo Michigan and now resides in Port Washington, NY with his wife Deb. Paul is primarily known for his work with comedian Louis CK, but has also shot features, documentaries and series-based shows such as the Hulu comedy, “Deadbeat”. Paul will be taking part in a panel discussion for the upcoming Manhattan Edit Workshop event September 30th, 2015 along side other cinematographers such as Nancy Schreiber, ASC (November, The Nines, The Comeback) Matt Porwoll (Cartel Land, Crisis Hotline: Veterans Press 1), Jerry Ricciotti (Vice, Vice News), and Bob Richman (An Inconvenient Truth, The September Issue, Paradise Lost: the Robin Hood Hills Child Murders).

Paul is originally from Kalamazoo Michigan and now resides in Port Washington, NY with his wife Deb. Paul is primarily known for his work with comedian Louis CK, but has also shot features, documentaries and series-based shows such as the Hulu comedy, “Deadbeat”. Paul will be taking part in a panel discussion for the upcoming Manhattan Edit Workshop event September 30th, 2015 along side other cinematographers such as Nancy Schreiber, ASC (November, The Nines, The Comeback) Matt Porwoll (Cartel Land, Crisis Hotline: Veterans Press 1), Jerry Ricciotti (Vice, Vice News), and Bob Richman (An Inconvenient Truth, The September Issue, Paradise Lost: the Robin Hood Hills Child Murders).

Let’s go all the way back to the first project that appears on your IMDB page – Adam Clayton Powell. What can you tell us about working on that project?

Do they have me listed as cinematographer for that project? Wow, so hard to remember! It was eons ago. I was actually an assistant on that project for an old friend of mine, Denis Maloney, who is a DP on the West Coast now. We were doing little projects all the time together, and we probably threw an extra camera into an interview and then someone put my name on the credits or something like that. And then decades later they list it on my IMDB page.

It was a good, noble project, if I recall. I’m not sure if there’s a place to watch it but there are countless other projects like that. I’ve been doing this for a while, and in those days, on documentaries, industrials and corporate work, you had to fly by the seat of your pants every day. Boy, you learn to think and act fast, or you will crash and burn. I look back on those days and that kind of work and I think maybe no one gives a hoot now, maybe it’s not even posted up there, but those were the days I learned how to think on my feet, how to figure stuff out, how to collaborate with people.

How do you navigate the quick pace of creating content and the ever changing world of logistics?

By the seat of my pants! Listen, it’s a real challenge. My projects tend to be smallish and I kind of like that. I think you can be more nimble on small projects. I get really bored on large projects where I sit around and wait 4 hours to set up a 15-second shot. That’s not what turns me on. But it doesn’t matter whether you are shooters like me, or the cinematographers who shoot big features. They have to make their day; they have to get their work done. And as the new technology keeps coming along you better damn well keep up with it.

The bottom line is we’re still telling stories, we’re being asked to do a lot in a short period of time. Productions are in the business of making money and we’re being asked to do a lot within the budget we have.

Who are some cinematographers that you admire?

Oh, wow! There are so many. I’m going to go back to my graduate days at NYU in the late 70’s. Caleb Deschanel, Michael Chapman, William Fraker… When I think of Raging Bull, that was Chapman, I saw it the first week it was out at the Ziegfeld and it just blew me away.

What are your thoughts on how cinematographers use technology these days?

I think we live in an amazing time, technologically, and things are going to continue to change at an ever-quickening pace. Whatever era we find ourselves in, we’re asking technical questions, and we’ve been doing that all along. A while ago it might be what aspect ratio are we going to shoot? Maybe you’re planning on doing widescreen but then you’d have someone say “well, you know, we’re gonna have to letterbox this or it will be cropped for that.” I guess we’re still doing the same thing, fighting these different formats. It comes down to who is your audience, how are they going watch it? Is your aunt Edna gonna watch it on a black and white Zenith? It’s one of those things you still contemplate.

Now, it cracks me up, we’re tossing out HD for UHD and beyond. I hear DPs all the time poo-pooing technology that would’ve blown their socks off if they could’ve imagined what was coming around the corner a few short years ago. And folks are watching on iPads balanced on their bellies.

Twenty years ago this industry felt very small. I know people all over the world were doing it, but it just felt like a small world. When I was in film school you had to have a wad of cash to take it to the next level. Good grief, now with the new iPhone, you have a 4K camera! Now with a modest sum of money you can produce, at home, a feature you could run up on a giant screen. You have that at your fingertips. But you still need a compelling story to tell. And that’s what I tell people. The technology is there; now try to tell a compelling story.

As the author of On the Wind and a Prayer, how does writing help you as a cinematographer?

Well just a quick set up, I was compelled to write that book as a way to convince myself I was taking a trip with my wife on our sailboat. Normally I’m a homebody – I like small adventures – but Deb convinced me to do something way out of my comfort zone. At some point you have to put the beans and rice in the boat and take off, and I needed convincing I was going to do it. It turned out a great experience, living on a boat for a year, running it down the Atlantic coast over to the Bahamas.

I started out with an English degree and for me everything starts with the script. I love words, I love when they’re well chosen. And when you get a script you read it over and you realize how much you can change a story by removing or altering a scene. Seeing those elements as they live on the page goes a long way toward visualizing your work.

Tell us about the gear you’re currently using. Anything that makes it your preference?

When it comes to cameras, I’m temped to say I don’t care! It’s a topic that has become tiresome to me. But the short answer is that I talk to the producers involved on a project I’m being interviewed for and ask them what they have used, and do they prefer a particular system. Right now I’d list those cameras that are main contenders out of the gate. RED, Alexas those are all out there. The Sonys, I’ve worked with the F55s, F5s, Canons, C300, C500s. They’re coming so fast off the assembly line. I’m mostly familiar with the REDs, and that’s because Louie force-fed me that system years ago. He knew about those before I did!

When it comes to cameras, I’m temped to say I don’t care! It’s a topic that has become tiresome to me. But the short answer is that I talk to the producers involved on a project I’m being interviewed for and ask them what they have used, and do they prefer a particular system. Right now I’d list those cameras that are main contenders out of the gate. RED, Alexas those are all out there. The Sonys, I’ve worked with the F55s, F5s, Canons, C300, C500s. They’re coming so fast off the assembly line. I’m mostly familiar with the REDs, and that’s because Louie force-fed me that system years ago. He knew about those before I did!

They’re all amazing to me! In my opinion if you shoot it right, if you know what you’re doing, and that’s a big IF, it’s going to look great! But many of us pretend to know more than we do about these systems. I remember sometime back, Louie’s show got an Emmy nomination, and when they played the small clip during the ceremony I remember thinking “What the hell happened to our material?” It looked like someone dubbed over a VHS copy of a VHS copy.

And my point is you have to have someone who knows these systems from beginning through to completion or you run the risk of people trying hard, having the best intentions, and it doesn’t look good in the end. So if I’m working with a company that already owns C300’s, then why wouldn’t we shoot with their C300’s? I’m not going to be one of those guys who comes in and says that we can’t use a camera system because it’s not what I prefer. That’s not how I work. Again, it’s a business. If there’s a system in place that produces great images and can save the production a bundle then that’s the whole point, isn’t it? You want to tell a compelling story and not have to go bankrupt doing it.

You’ve done a lot of work with Louis CK, but aside from the TV show, you’ve shot many of his specials. Do you try to capture something different about him and his performance in each, or is it more about maintaining consistence?

Obviously there are some things fundamentally different that will go into the making of one of his specials versus a TV show, but either way I always try to talk to Louie and find out what he wants and what he’s trying to do.

For example, we did the show in Phoenix for “Oh My God” as an homage to George Carlin. Louie wanted to do the show there because that’s where George did one of his specials, so it’s really just trying to first figure out what Louie wants. He generally likes the intimacy of cameras placed close to him, whether he’s in a small venue or a large one.

Louie seems to maintain almost total control over every aspect of the TV show, how much of the camera decisions does he leave up to you?

Not much, let me tell you. In terms of the lighting and camerawork, he’s as hands-on as it gets. Like I said, he was the one who wanted to shoot with the RED cameras years ago. I think the first time we used them for his special at the Pabst Theater in Milwaukee. At first he was really talking them up and I had heard about them but I didn’t know much about them. I knew they would be a challenge because they were very new, with not much in the way of support for them. We were sourcing gear from all over the country to do the job. But he really wanted them so I figured it out and we went with it.

But there are certain things that we just both agree on and are of the same mind about. Like the crane shots, I call them the Emmy swoops, a lot of people will stick a camera on a big arm and they swing that thing down and do a Superman shot. That’s the last thing on Louie’s mind. It’s about subtlety; it’s about intimacy.

In terms of camera movement, or the mood created by lighting, again, he can be very specific. I really like to use a small jib a lot, but we still incorporate a lot of handheld, and in recent years he’s turned more and more to Steadicam, with very satisfying results. And he’s personally steered me away from more conventional lighting. We do a lot of existing-light stuff, and I have to thank him for breaking me of some old habits.

On the show, it seems like there’s not a lot of perparation, seems like you roll in and start shooting. Is that kind of setup your preference, or are you simply able to adapt and do whatever is necessary?

Yeah, just adapt. Listen, I show up early to set knowing the script. I try to put the people and pieces in place and wait for Louie to arrive. There is rarely any rehearsal, as he likes to start rolling right out of the gate, and it usually yields very interesting results. I find it exhilarating.

I mean every job is different, but I look at everything, like am I going to be near home, what size is my crew, where exactly will we be, these are the important things to consider when saying “yes” to a job. Will you have enough time to discuss these things with the people who are responsible for the production? What will they want, what do they expect and are those expectations realistic? Do I have what it takes to deliver to those expectations? You just have to think wisely about what can be done with the time and money allotted.

Any new projects on the horizon for you?

I’m going back for Season 3 of “Deadbeat”. I was able to shoot Season 2 and they’ve asked me back. It was a real challenge for me on Season 2. I’m not a VFX guy and it was a challenge to be working on location with a lot of green screen material so often.

I’m going back for Season 3 of “Deadbeat”. I was able to shoot Season 2 and they’ve asked me back. It was a real challenge for me on Season 2. I’m not a VFX guy and it was a challenge to be working on location with a lot of green screen material so often.

I didn’t think I’d return. It’s kind of like walking in and seeing a mother who’s just given birth to twins and asking her if she would want another baby, the mother would be like “Get out of my face!” That was me after Season 2. But you know, a year goes by, the kids turn out cute and you think sure, why not!

So I’m going to do that. But this time I want to do it better. I want to deliver the best product I can, and fix some things that didn’t go so well last time. I want to put together a crew who get along well and understand each other and the task at hand, to see Production as collaborators and not adversaries. I want to be able to get our days in, do well, go home and get some sleep so everyone WANTS to come back the next day!

Bobby Marko is an award winning filmmaker based in Nashville, TN. A retired professional musician turned filmmaker, Bobby has covered the world of film and video, from live production and chroma key capture to short films and feature length documentaries. He’s had published articles at Cannes Film Festival and has been a featured presenter at IBC in Amsterdam. Bobby’s passion is to capture the heart of a story through moving imagery and share his experience along the way. You can catch his podcast show on iTunes and Soundcloud, the Authentic Filmmaking Podcast.

Bobby Marko is an award winning filmmaker based in Nashville, TN. A retired professional musician turned filmmaker, Bobby has covered the world of film and video, from live production and chroma key capture to short films and feature length documentaries. He’s had published articles at Cannes Film Festival and has been a featured presenter at IBC in Amsterdam. Bobby’s passion is to capture the heart of a story through moving imagery and share his experience along the way. You can catch his podcast show on iTunes and Soundcloud, the Authentic Filmmaking Podcast.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now

@MarkoVisual

@MarkoVisual