Editors discuss pacing and rhythm as primary ways that they ply their art. But how does that really matter to the art of editing?

Editors discuss pacing and rhythm as primary ways that they ply their art. But how does the rhythm of an edit, or the pacing of shots, or the greater pacing of an entire story matter to the art of editing?

Editors discuss pacing and rhythm as primary ways that they ply their art. But how does the rhythm of an edit, or the pacing of shots, or the greater pacing of an entire story matter to the art of editing?

Why not just cut three second shots one after another for an entire video? Or why not just figure how big your hole is that needs to be covered and divide the length by the number of good shots you have to cover it and make that number be the length of your shots? Why not just put a music bed under your video and cut on the second or fourth beat over and over and over? That’s rhythm, right?

Maybe we can learn something from one of our creative colleagues in one of the other arts.

There are a few other art forms that use rhythm and pacing. Dance, obviously. Music is another. The percentage of editors that I know who are musicians is very high.

Another art form that relies on pacing and rhythm is writing.

There is a fantastic example of rhythm and pacing developed by the writer, Gary Provost. Gary provides this great mini-essay on his website.

I have broken it up to look a little more like shots in a scene in a vertical timeline.

This sentence has five words.

Here are five more words.

Five-word sentences are fine.

But several together become monotonous.

Listen to what is happening.

The writing is getting boring.

The sound of it drones.

It’s like a stuck record.

The ear demands some variety.

Now listen.

I vary the sentence length, and I create music.

Music.

The writing sings.

It has a pleasant rhythm, a lilt, a harmony.

I use short sentences.

And I use sentences of medium length.

And sometimes when I am certain the reader is rested, I will engage him with a sentence of considerable length, a sentence that burns with energy and builds with all the impetus of a crescendo, the roll of the drums, the crash of the cymbals–sounds that say listen to this, it is important.

By Gary Provost

There are great editing lessons that can be derived from this writing lesson. I don’t think the lesson is completely transposable, but I definitely agree with the main point, which is that when things are predictable and homogenous, they are boring.

Do I think that you should make every shot a different length? Absolutely not. If every note in a piece of music was a different length, it would be unlistenable. Music uses a combination of similar rhythms and changes in that rhythm to create something that is both pleasing and surprising or interesting.

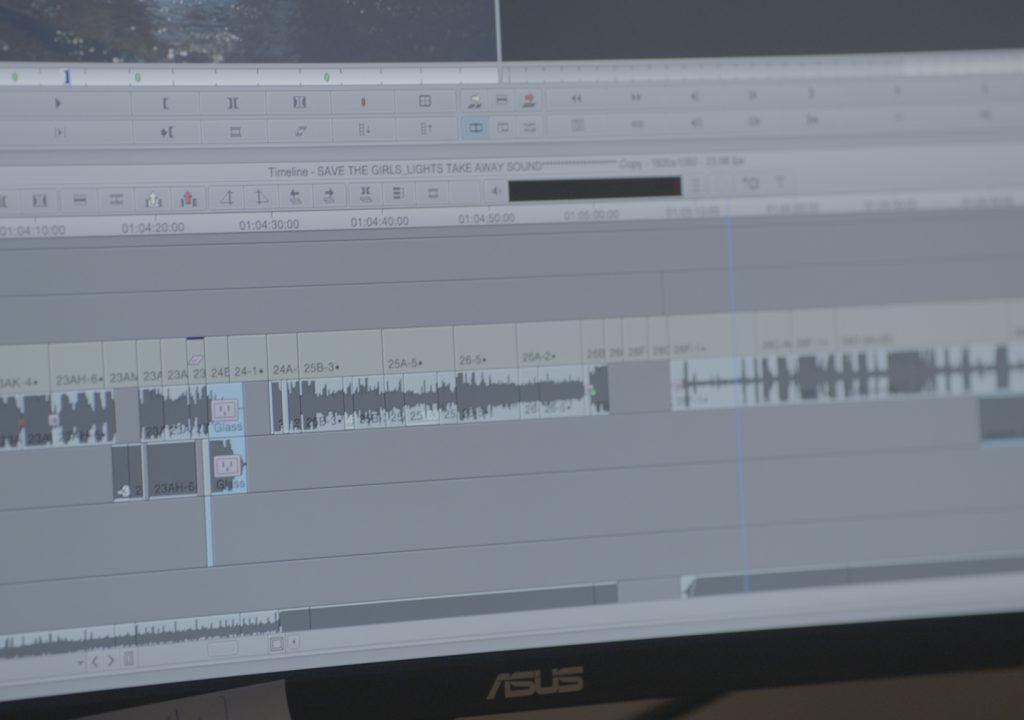

As I edit, I try to keep this in mind. When pacing an edit, I have a clock going in my head as the shot plays. The clock depends on a lot of things. It depends on the length of the shot before it. It depends on the interest level or quality of the shot. It depends on the movement in the shot. It depends on the energy level of the voice over or the interview or on-camera delivery. It also depends on where in the video I am. Do I want to start fast and slow down later? Or maybe I want to build in speed to a big finish? It also depends on the length of the entire video. For example, while a series of sub-one-second edits may be sustainable for a 30 second promo, it is not sustainable for an hour long documentary. But what I definitely don’t want to do is have it all be the same from start to finish. When I edit, I try very hard to not use all “five word sentences.”

Similar to writing is storytelling. Any good storyteller has a sense of both rhythm and pacing. My dad used to tell this particular ghost story around the campfire when I was a kid. It started slowly, mysteriously. His speech was slow. The exposition of the story was slow. It built a sense of mystery and expectation. But then, as he started to build towards the climax of the story, his sentences got shorter. His delivery got faster and faster. Then as the final revelation was about to occur … a pause for dramatic effect … and the release and gentle conclusion and warning. All pacing and rhythms.

A joke is essentially just a very short story and we all know that with a joke, timing is everything. Timing in this case is all about the pace of the telling and the rhythm of the release and punchline. Even a comic with a seemingly monotone delivery, like Steven Wright, has a tremendous sense of pacing as they set up and reveal information. Many of the jokes have a lightning fast delivery of exposition followed by a paced delivery of multiple punchlines or points where the audience needs to come to a realization of something.

So when you think about what it means to pace your edit or have rhythm, consider that this doesn’t mean that you can make a cut on a beat. Consider that the audience needs some sense of both predictability and surprise. In music, pacing is often defined merely as tempo. Yet, tempo is merely the base time against which the rest of the music plays out.

So when you think about what it means to pace your edit or have rhythm, consider that this doesn’t mean that you can make a cut on a beat. Consider that the audience needs some sense of both predictability and surprise. In music, pacing is often defined merely as tempo. Yet, tempo is merely the base time against which the rest of the music plays out.

The tempo of a piece of music may stay completely consistent throughout an entire piece of music, but it can still be paced, with sections of eight or sixteenth notes followed by the release of a whole note or rest. Think of the William Tell Overture (The Theme to the Lone Ranger) if it was missing the long hold just before the fast “to the dump, to the dump, to the dump, dump, dump” part. The music is paced beautifully.

The tempo of a piece of music may stay completely consistent throughout an entire piece of music, but it can still be paced, with sections of eight or sixteenth notes followed by the release of a whole note or rest. Think of the William Tell Overture (The Theme to the Lone Ranger) if it was missing the long hold just before the fast “to the dump, to the dump, to the dump, dump, dump” part. The music is paced beautifully.

Dance has pacing and rhythm as well. Dancers and choreographers do not simply make a movement or step on every single beat. The beautiful flow of a well choreographed dance is something we can all aspire to as editors. Dance rushes forward, then holds, then flows elegantly, then spins and drives. Some things happen on the beat and there are times when beats go by with no motion… the movement is suspended for a moment, not arbitrarily, but in a deliberate, paced way. When has the audience had enough speed? When does the eye need to rest on a beautifully held form in preparation for the next rush of movement or subtle gesture?

As a good exercise, watch some videos without audio. What is the pacing? What is the rhythm of the edits without reference to the underlying sound?

Some of my Art of the Cut interviews discuss pacing and rhythm. Specifically the interviews with Joe Walker and my upcoming interview with Frontline’s Steve Audette.

As editors, we need to always be learning throughout our careers. Often, that learning focuses on software. Software comes and goes, but learning and practicing the fundamental skills that are software independent are the surest bet to distinguishing yourself in an increasingly crowded workforce.

Steve Hullfish is a feature film editor and national TV editor. He trains professional editors around the world for networks, studio and TV stations including NBC Sports, Turner Networks, The Golf Channel, Vietnam TV, Major League Soccer, and PBS. Follow him on Twitter: @stevehullfish

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now