Kirk Baxteredited one of the first major feature films cut in Adobe Premiere Pro. He has worked primarily with director David Fincher, winning Academy Awards for “The Social Network” and “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.”

Kirk Baxter is a film editor who has worked primarily with director David Fincher, winning Academy Awards for “The Social Network” and “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo,” as well as a nomination for “Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” and two primetime Emmy nominations for “House of Cards” and “Big Love.” His peers at ACE have recognized him with a nomination or a win nearly every year since 2009.

HULLFISH: One of the reasons I’m very interested in speaking to you – besides your pedigree as a multi-Oscar-winning editor – is that most of the editors I interview work on Avid, and you are one of the few major editors cutting in Premiere. Were you on Avid originally?

BAXTER: I’ve cut on Avid on music videos and commercials, but I’ve never cut a movie on it. “Gone Girl” was Premiere.

HULLFISH: “Zodiac” was Fincher, so that would have been Final Cut, right? “Curious Case of Benjamin Button” was Final Cut?

BAXTER: Yup.

HULLFISH: I’ve only cut three films, but they’ve been one each on Final Cut, Avid and Premiere.

BAXTER: What do you think of Premiere?

HULLFISH: I think I like it better than I did Final Cut – and I’m a huge Apple fan and cut in FCP for many years – but Premiere is just very, very slow with a lot of media. If you cut on Premiere on short projects, like TV spots or promos, I think it’s great. I actually cut my Avid tutorials in Premiere! I like the tools, but when you get up to the level of a feature film – and your opinion is better than mine – it’s a little draggy and launching the project takes forever. I mean, the project launches immediately, but it can be multiple minutes before you can do anything while the media is connecting. On an Avid, it’s much more responsive. But there’re a lot of good things to say about the editing tools in Premiere: many of them superior to Avid. Each of the NLEs has things in it that you miss when you move to one of the other platforms.

BAXTER: I’m a terrible one to quote because I get all the jargon wrong and wind up the engineers. Premiere was slow at first when we were doing “Gone Girl” but we had engineers on hand improving it and ultimately changed the wayPremiere looked for everything when it was opening a project. What used to take 10 minutes to open up a project correctly without it stuttering and stepping got really reduced down to 2 minutes or a minute and a half.

BAXTER: I’m a terrible one to quote because I get all the jargon wrong and wind up the engineers. Premiere was slow at first when we were doing “Gone Girl” but we had engineers on hand improving it and ultimately changed the wayPremiere looked for everything when it was opening a project. What used to take 10 minutes to open up a project correctly without it stuttering and stepping got really reduced down to 2 minutes or a minute and a half.

HULLFISH: I wonder if those changes have made it into the main software or whether that was just for you, because that’s my big problem, too.

BAXTER: It was a problem of mine and they worked on it consistently and by the end of the movie it was radically better. We’ve done one TV show with Fincher since then and it was perfectly fine during that.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about “Gone Girl” a little bit. I just watched it again. One of the fascinating things to me is the structure of a story and “Gone Girl” has one of the most interesting structures in a film that I can remember. It’s very unique in how it deals with time. How much of that structure was present in the original script and how much was determined in the editing room?

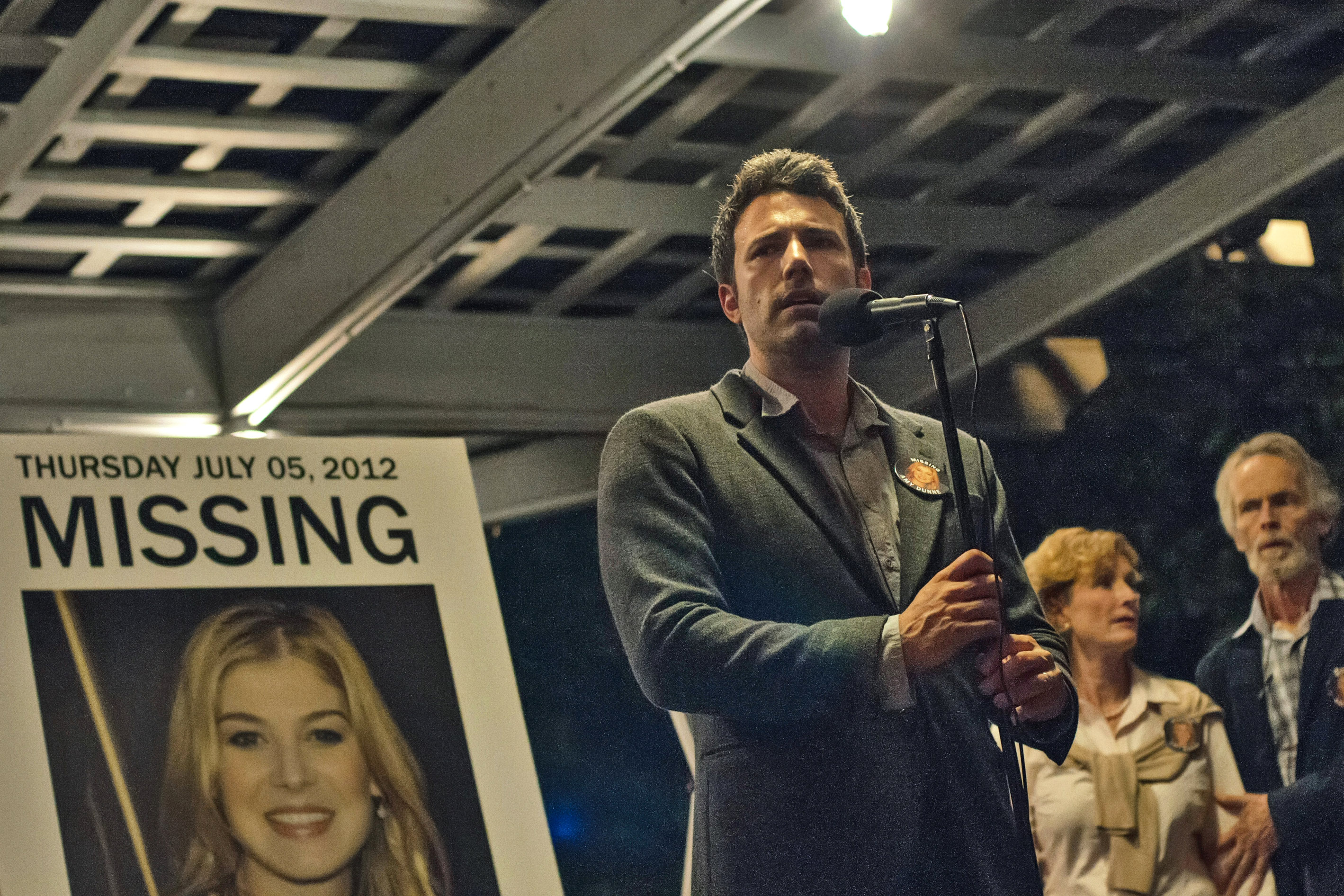

BAXTER: (pictured on-set with ubiquitous Hollywood extra, Jesse Heimann) Most of it was “as written.” I’m sure David worked with Gillian (Flynn, screenwriter) in the streamlining of it. But when you follow it strictly, you end up with a longer movie. So I find my role with Fincher to be not so much the re-writing of the order of things, but the streamlining of things. There was a lot of written back-and-forth between present day and the past, told through the diary in the middle of the film – and as the momentum started to build up, I reduced the back-and-forth and put a lot of the flashback material together into one movement so that you could stay with the whole procedural part of the film, and I think that reduced time and …

BAXTER: (pictured on-set with ubiquitous Hollywood extra, Jesse Heimann) Most of it was “as written.” I’m sure David worked with Gillian (Flynn, screenwriter) in the streamlining of it. But when you follow it strictly, you end up with a longer movie. So I find my role with Fincher to be not so much the re-writing of the order of things, but the streamlining of things. There was a lot of written back-and-forth between present day and the past, told through the diary in the middle of the film – and as the momentum started to build up, I reduced the back-and-forth and put a lot of the flashback material together into one movement so that you could stay with the whole procedural part of the film, and I think that reduced time and …

HULLFISH: … kept the flow going. There were a lot of jumps in time. That’s kind of a common thread of these discussions with editors is when and how to skip time and when to extend it – where time is not continuous. Did you need to do a lot of those time compressions to get the film to time?

BAXTER: Whether it’s to get it to time or not it’s something I naturally look for. Fincher calls it “shoe leather scenes.” It’s just boring watching people go through the paces unless there’s a pile of tension around that particular moment, then you want to expand it out. But if it’s just one person traveling from A to B, you just need to suggest the places, give people grounding and move on.

HULLFISH: I did an interview with Joe Walker who did “Sicario” and “12 Years a Slave…”

BAXTER: Oh! “Sicario” was fucking great.

HULLFISH: So, I did an interview about “Sicario” and one of his great quotes from that interview was “Man there are a lot of doors in this movie!” People walking through doors.

BAXTER: Doors are tricky to edit. I’ve always found doors tricky to edit. The way Fincher covers it is you get the beginning, middle and end of everybody’s coverage from both sides of the door, so when you’re presented with it as an editor you have to say, “Who do I want the door to open on? It can be on this person, or we can flip it and it can be on this person, or we can try to show a bit of both.” It’s so open to do whatever the hell you want.

HULLFISH: In “Gone Girl” you would often cut scene to scene or even inside of scenes, jumping in time with just cuts, but there were several dips to black, like one where the police detective says, “Your wife is ‘Amazing Amy?'” and then it fades to black and fades up on a diary of the character repeating that name.

BAXTER: The fades to black were always triggers that we were going back in time. We did that consistently to help the audience. But I found that it was too pedantic to do it on the exit as well, so we just cut back.

HULLFISH: Just what I noticed. Cuts forward in time.

BAXTER: Yeah, I just allowed us to slam back into the story and we only sort of did that stop/reset when we went back in time. At one point- I think there are four different roads all converging at the same time when he comes up to the woodshed, that’s the only time I stopped doing the fades to black and I kind of mashed it all together into one montage, because I think by that time the audience has learned what’s going on and it doesn’t matter whether it happened before or whether it’s happening now. You just sort of slap them in the face with all of it at once. That was the hardest scene to edit.

BAXTER: Yeah, I just allowed us to slam back into the story and we only sort of did that stop/reset when we went back in time. At one point- I think there are four different roads all converging at the same time when he comes up to the woodshed, that’s the only time I stopped doing the fades to black and I kind of mashed it all together into one montage, because I think by that time the audience has learned what’s going on and it doesn’t matter whether it happened before or whether it’s happening now. You just sort of slap them in the face with all of it at once. That was the hardest scene to edit.

HULLFISH: Another thing I noticed was that we were definitely coming into scenes in their middle and sometime leaving scenes in their middle. Is a lot of that trying to shorten the movie, or keeping the pace up, or it’s just the way it was written?

BAXTER: Most of that was probably us shortening it in the edit room. I can think of a couple of examples of what you’re mentioning. We initially had a great scene when Nick was playing Tetris all by himself in the interrogation room and they’re watching him, saying “What the hell’s wrong with this guy? His wife’s missing.” That scene got dropped, and you create new ways to kick scenes off. there are probably better examples but David films hundreds of hours and I have all of this stored and logged in my brain, ready at a moment’s notice, and as soon as the movie wraps I just flush it.

HULLFISH: You’ve got to make room for all that same kind of information on the next movie, right?

BAXTER: You can’t carry it around with you. But the moment I watched the movie, it all comes racing back.

HULLFISH: At one point, I thought I was listening to a sound effect, but it goes over several scenes and I finally figured it was score: as Nick is cleaning up his shattered drink glass.

BAXTER: Yeah, that’s music. Trent (Reznor, composer) and Atticus (Ross, composer) who did the score, at first they provide a bunch of tracks that aren’t supposed to be anywhere in particular. It’s just music for the film, and that was one that sounded like it wasbuilt out of cameras, like paparazzi clicking. That moment when he starts sweeping up the glass is the scene that leads Nick out into the woodshed and that becomes a montage of all story lines crashing together before the movie does its complete 180 U-turn. I put that track on in the rough assembly just to work to and it stuck.

HULLFISH: I liked it and thought it was very similar to some of the weird stuff that was in “Sicario” that was very percussive and put the hair up on the back of your neck.

HULLFISH: I liked it and thought it was very similar to some of the weird stuff that was in “Sicario” that was very percussive and put the hair up on the back of your neck.

BAXTER: That was a great film (“Sicario”). I watched that about two weeks ago. To me it’s the best film of the year so far. I watched “The Martian” last night. That’s coming up a close second behind it.

HULLFISH: I’ve done interviews on both those films. Actually I interviewed Pietro Scalia for “The Martian” and then for all the technical stuff, I interviewed his additional editor, Cheryl Potter. I don’t know if you’re like this, but Pietro’s not really concerned about any of the technical stuff going around him. He says, “I just walk in in the morning and they tell me what scenes I have to cut and they’re ready for me.” So all the technical stuff I needed I got from Cheryl.

BAXTER: I’m very, very, very much the same. Tyler Nelson, my assistant on all of David’s movies, is the reason I’m on Premiere. He wanted to move it to Premiere for all of the After Effects that were going to take place and the general workflow.

HULLFISH: And there was a lot of After Effects in “Gone Girl?”

HULLFISH: And there was a lot of After Effects in “Gone Girl?”

BAXTER: Always with David. Even if it’s just stabilizing. He stabilizes almost every shot. Not automatic computerized random stabilizing, but by hand, It’s an art. pinning where you want it to move and stop and reframe. He throws blue-screen everywhere you see, out of every window. So there’s enhancement of everything, even if it’s not just strictly an effects shot.

HULLFISH: Yeah, the indie I’m doing right now, the director thought there would be three effects shots and right now we’re at about 100.

BAXTER: Yeah. It’s so easy to do. David overshoots everything – I don’t mean in terms of coverage – but it terms of framing, so we have room to reframe and with that it makes it really easy for me to split screen and re-timeactors. If you’ve got two actors on screen at the same time I’m almost always doing a split screen and re-timing their actions or choosing different takes. And then the in house effects team seamlessly join it back together again. So that stuff is always taking place in the background.

HULLFISH: I did that in a scene with three actors. I tried cutting it together with separate close-ups, but it got too cutty. The scene played best in the wide, but the only way to get the timing right was to split the screen and use a different take of the actor in the middle.

BAXTER: I find that where your eyes mostly focus, I’ll time it around that person and then the person that’s on the over-the-shoulder, I’ll be speeding up in between with little 50 percent speed-ups, so that their reactions are twice as fast. I find that when two actors are talking, when you take that normal pacing and drop it into a nearly finished film, it’s way too slow, 9 out of 10 times. You have to kind of pep it up to meet the pacing of the entire scene.

HULLFISH: So let’s talk about that. Obviously, the other way to pace up that scene is to just cut from wide to close to close…

BAXTER: But if you’re in a situation where you’re cutting for every single line, you can end up looking a little “TV.” – Well, TV is pretty fucking good these days. – Unless you’re cutting to people listening. I look for opportunities to not have to cut for every line. If I can play out two or three lines on one shot, then I’ll do so. But I usually have to use those tricks of splitting the screen to be able to do it.

HULLFISH: Does Fincher tend to lock off those wide shots?

CLICK “NEXT” BELOW TO CONTINUE READING

BAXTER: He’ll do camera moves to bring you into a scene or bring you out of a scene and sometimes he’ll do them when a character moves from one side of the room to another. If he does a pretty elaborate camera move it’s usually because he wants to see it (in the final film) so I’ll put little markers to say, “I’ll be on this shot for this moment in time.” Then I know it’s free-range for everything around it. Then I’ll get into the weeds with all the nitty-gritty of performances before and after those camera moves. Like, if I’ve got a two shot and a single on a certain actor’s face and it’s a three minute scene, but in the middle of that scene there’s a camera move from here to there, I know I don’t have to scrutinize all of their performances for that camera move part. I can safely be in the coverage of the wide shots that are going to move us out.

HULLFISH: I noticed – perhaps because I’ve known many twins – that in the twin scenes, the dialog between them is very tight – almost like they’re reading each other’s minds or are finishing each other’s thoughts. Was that intentional?

HULLFISH: I noticed – perhaps because I’ve known many twins – that in the twin scenes, the dialog between them is very tight – almost like they’re reading each other’s minds or are finishing each other’s thoughts. Was that intentional?

FINCHER: We purposely cut the dialog between the twins at a faster than usual pace. Fincher liked the idea that they were always on top of each other, ready to finish each others thoughts. That always made the pauses in their scenes work so much harder.

HULLFISH: Talk to me a little bit about your approach to a scene like that. Give me a little detail about how your assistant sets that scene up for you and then how you tackle if from beginning to end. You mentioned that you knew that if Fincher does a big camera move, it’s probably because he wants to see that in the edit. How do the assistants prepare your bins?

BAXTER: I just look at text view. But I have them cut the dailies into sequences back to front, so if they’ve done 12 takes, I look at the last one first and work my way backwards. Because if I look at it front first, I say, “That one’s good…oh, that one’s good too…” but if I look at it backwards, I can usually see it deteriorate and I end up with a more focused selection.

HULLFISH: Then do you actually work from the selects reels or do you just use them for screening purposes.

BAXTER: No. I work from the selects reels. The very first thing I’ll do is take a look at every single angle that he shoots for a scene so I have an idea of the movement of the scene and if he’s got close ups, big close-ups of objects and things, I know where the audience needs to be directed. So after I’ve watched everything and have an understanding of it, then I’ll look at the last take of each scene and mark it up for breakdowns by my assistants. So if it’s a three minute scene that has 30 lines, I’ll start doing add edits in each spot that I think an edit would naturally take place. So instead of now watching a master as a one-take piece, I’ll watch it as probably eight chunks. And then I’ll have every take separated the same way and joined together. So now instead of trying to judge one shot that’s three minutes long and it’s impossible to remember perfectly each little moment, I’ll just be judging tiny beats next to each other and it’s really easy to determine when somebody nails a particular part of it.

HULLFISH: I love that method. I’m going to have to steal that. That’s great.

BAXTER: Fincher covers everything in such depth that you know you can aggressively cut it. If you’ve only got a scene with a wide shot and one over-the-shoulder, then I probably wouldn’t break it into a thousand pieces because all you’re going to be doing is going back and forth between the two things. If he’s going to shoot something that simply, he’ll shoot it with an A and B camera, so I’ll pre-cut every take between the A and B so I can kind of watch it how I intend to use it. It’s a long laborious process, but I find that it’s the most accurate way to make sure I’m using the best material. Then after I’ve selected everything, I’ll assemble it all together so that for any particular line there might be three takes of that line in the master, three takes of that line in an over-the-shoulder, three takes in a 2-shot, three takes in a close-up for every beat in the scene. I’ll play that down – it might be a three minute scene, but now it’s 12 minutes of dailies. Then I’ll share that with David and he’ll go through it and say, “Great…nope, yup… good” and then, once I’ve got that feedback from him I cut it together. And after I put it together I may have to go back to the dailies if I’m missing something.

BAXTER: Fincher covers everything in such depth that you know you can aggressively cut it. If you’ve only got a scene with a wide shot and one over-the-shoulder, then I probably wouldn’t break it into a thousand pieces because all you’re going to be doing is going back and forth between the two things. If he’s going to shoot something that simply, he’ll shoot it with an A and B camera, so I’ll pre-cut every take between the A and B so I can kind of watch it how I intend to use it. It’s a long laborious process, but I find that it’s the most accurate way to make sure I’m using the best material. Then after I’ve selected everything, I’ll assemble it all together so that for any particular line there might be three takes of that line in the master, three takes of that line in an over-the-shoulder, three takes in a 2-shot, three takes in a close-up for every beat in the scene. I’ll play that down – it might be a three minute scene, but now it’s 12 minutes of dailies. Then I’ll share that with David and he’ll go through it and say, “Great…nope, yup… good” and then, once I’ve got that feedback from him I cut it together. And after I put it together I may have to go back to the dailies if I’m missing something.

HULLFISH: That’s a fascinating method. I like that.

BAXTER: It’s laborious but it gets there in the end.

HULLFISH: So the dailies as individual clips and their organization in the bin is not that important to you, because you’re almost always working from some sort of selects reel or cut-down.

BAXTER: Most of the time, correct. But when I return back to dailies, they’re all broken up into little bite sized chunks anyway, so it’s really easy to go back and review and double-check that you’ve got the right bit of something because you don’t have to scrub for it. So it’s a massive amount of labor up front as the dailies are coming in, but it makes the back-end very simple. It works really well for Fincher and the style of how he shoots. I can’t say that it would work for every director, but it certainly does for him because you get a lot of multiple takes all aiming for a similar thing, rather than that kind of coverage where I think a lot of directors will just get three cameras on a scene and each camera’s getting different things and it’s more haphazard and documentary. For that style, I’d have my little selects reel and I’d rarely go back to the original dailies again, because it’s all like a needle in a haystack.

BAXTER: Most of the time, correct. But when I return back to dailies, they’re all broken up into little bite sized chunks anyway, so it’s really easy to go back and review and double-check that you’ve got the right bit of something because you don’t have to scrub for it. So it’s a massive amount of labor up front as the dailies are coming in, but it makes the back-end very simple. It works really well for Fincher and the style of how he shoots. I can’t say that it would work for every director, but it certainly does for him because you get a lot of multiple takes all aiming for a similar thing, rather than that kind of coverage where I think a lot of directors will just get three cameras on a scene and each camera’s getting different things and it’s more haphazard and documentary. For that style, I’d have my little selects reel and I’d rarely go back to the original dailies again, because it’s all like a needle in a haystack.

HULLFISH: I’m interested in the fact that you show him all the takes in this cut-down style. Obviously, all directors watch the dailies, but for him to look at an edited selects reel…

BAXTER: It’s very specific because it’s broken down into moments. He enjoys that. If I were to send him an edit straight away, that would make him a little itchy, because he’d say, “Well, what about all the other good stuff?” He covers a lot, so for him to be giving me a 15:1 ratio and for me to present one thing back and say, “This is the way it should be.” I’m sure he’d say, “Well, how did you come to that conclusion?” So I find when I share the process of the reduction, he’s at ease knowing that things are being vetted and that the choices are there. And as it gets further along… because we’re doing this as he’s shooting… so I’m three or four days behind camera. He’s seeing this in-between set-ups. He’ll log on and look at what I’ve recently sent him, and even after I’ve sent him a complete cut, he still might question a certain line. The next time I send it, it’ll be the scene as it was, but when it gets to that line, there will be three choices in a row of the best choices or just one or two, or I’ll take the audio from the best close up and put it into two different choices of the 2 shot. He likes multiple choice. I like to work that way as well.

HULLFISH: I love that method. I’m fascinated to hear you discuss it. I appreciate you walking me through that. Talk to me a little about a critical scene in “Gone Girl” where Amy is watching Nick on TV and there’s a ton of great reactions. Nick’s kind of talking to her through the TV and she’s completely engrossed in what he’s saying and the guy she’s watching TV with is completely disgusted and fed up. To add to that mix, Nick is watching himself on TV with his twin sister. The reactions were superb and really make the scene.

BAXTER: Thank you. I LOVE doing that sort of stuff. The more complicated it gets, the happier I am. It ends up so much richer and so dynamic and you feel proud of it in the end. It’s hard to do. It’s time consuming to do. You just need the time to do it. And with David, you’ve always got the coverage. In his movies, there have been a few scenes like that. In the first two episodes of “House of Cards” there was an interview that takes place on TV and everybody is reacting to the TV (When Frank sets up his rival to have a meltdown during a TV interview). The one in “Gone Girl” was even more complicated. The first way I cut it was just the interview itself. So I cut it as if it was live vision-switching in a studio. And there are a lot of takes for that as well so there’s a bunch of interplay in making it work as a base layer for what goes in the TV. Then I have the whole reaction of Amy watching it and setting that up and starting wide, showing where she is, slowly working in, knowing when the best beats and the best moments are within that scene. Desi (Neil Patrick Harris’ character) looking at Amy. How do you want that to land? What do you want that expression to land off? When do you want him to be fed up and grab his Champagne bottle? When do you want the noise of that to irritate Amy? All of those things have to play off the lines and they start to dictate to you how long you’re going to stay inside the screen and when you’re going to come back out… whether you’re going to be full-screen TV or see it from further away. And once I’ve got that built out, now it’s two layers. One is the screen and one is Amy. Then I bring in Nick watching TV at his sister’s house and the interactions with his sister. When’s the best time to be on HER to be disgusted. Now I have to start giving away on Amy’s side to fold in that last part. Then it’s a sweep through the whole thing so that we make sure it’s not confusing. How do you know where you are? How do you make it clear if you’re in Nick’s house or Desi’s house? We never crossed through TVs, we always crossed through people, so you didn’t ever cut from TV to TV. We went from character. The sound design helped a lot. The rooms had different feelings and the TV’s were of different quality: like Desi has a lot of money, so his TV had perfect scan lines and when you’re in Nick’s sister’s house she has a crappy TV. It’s such a rich ballet when things get that complex.

BAXTER: Thank you. I LOVE doing that sort of stuff. The more complicated it gets, the happier I am. It ends up so much richer and so dynamic and you feel proud of it in the end. It’s hard to do. It’s time consuming to do. You just need the time to do it. And with David, you’ve always got the coverage. In his movies, there have been a few scenes like that. In the first two episodes of “House of Cards” there was an interview that takes place on TV and everybody is reacting to the TV (When Frank sets up his rival to have a meltdown during a TV interview). The one in “Gone Girl” was even more complicated. The first way I cut it was just the interview itself. So I cut it as if it was live vision-switching in a studio. And there are a lot of takes for that as well so there’s a bunch of interplay in making it work as a base layer for what goes in the TV. Then I have the whole reaction of Amy watching it and setting that up and starting wide, showing where she is, slowly working in, knowing when the best beats and the best moments are within that scene. Desi (Neil Patrick Harris’ character) looking at Amy. How do you want that to land? What do you want that expression to land off? When do you want him to be fed up and grab his Champagne bottle? When do you want the noise of that to irritate Amy? All of those things have to play off the lines and they start to dictate to you how long you’re going to stay inside the screen and when you’re going to come back out… whether you’re going to be full-screen TV or see it from further away. And once I’ve got that built out, now it’s two layers. One is the screen and one is Amy. Then I bring in Nick watching TV at his sister’s house and the interactions with his sister. When’s the best time to be on HER to be disgusted. Now I have to start giving away on Amy’s side to fold in that last part. Then it’s a sweep through the whole thing so that we make sure it’s not confusing. How do you know where you are? How do you make it clear if you’re in Nick’s house or Desi’s house? We never crossed through TVs, we always crossed through people, so you didn’t ever cut from TV to TV. We went from character. The sound design helped a lot. The rooms had different feelings and the TV’s were of different quality: like Desi has a lot of money, so his TV had perfect scan lines and when you’re in Nick’s sister’s house she has a crappy TV. It’s such a rich ballet when things get that complex.

HULLFISH: Which “House of Cards” episodes did David direct and you edit?

HULLFISH: Which “House of Cards” episodes did David direct and you edit?

BAXTER: The first two episodes of the first season.

HULLFISH: Earlier you said, “TV’s getting a lot better” and the first thing I thought of was “House of Cards.” … Another one of your projects that has a very complex story structure is “Curious Case of Benjamin Button.”

CLICK “NEXT” BELOW TO CONTINUE READING

BAXTER: There are places in each of those movies, where you read the script, and it’s like a “dessert moment” for me as an editor. In “Benjamin Button” it was the moment leading up to Daisy in hospital and it’s all voice-over led from Brad Pitt’s character. It’s the sequence of “If only this orthat hadn’t happened.” It’s this massive sequence of coincidences – cab drivers and people getting a coffee or not getting a coffee and a shoelace breaking – that leads to this perfect moment in time. And I have hundreds ofshots and it just raced by at a relentless pace and the coverage is IMMENSE. You go through the alphabet two or three times in terms of how many set ups there are.

BAXTER: There are places in each of those movies, where you read the script, and it’s like a “dessert moment” for me as an editor. In “Benjamin Button” it was the moment leading up to Daisy in hospital and it’s all voice-over led from Brad Pitt’s character. It’s the sequence of “If only this orthat hadn’t happened.” It’s this massive sequence of coincidences – cab drivers and people getting a coffee or not getting a coffee and a shoelace breaking – that leads to this perfect moment in time. And I have hundreds ofshots and it just raced by at a relentless pace and the coverage is IMMENSE. You go through the alphabet two or three times in terms of how many set ups there are.

HULLFISH: To explain to someone not used to seeing dailies, each shot is given a number for what scene it is, and then a number for what take it is, and then the set-ups or camera positions and shot sizes within that scene are labeled with letters, starting at A, for each set-up and usually, going through maybe G or H or possibly T (in my experience) but you’re saying there were maybe a hundred set-ups, each with possibly multiple cameras for this one scene?

BAXTER: Yes. But when it’s put together it’s just seamless. It’s perfect and it’s because of the coverage. When I read it, I said, “I can’t WAIT to get my hands on that.” It was the same thing in “Gone Girl” the scene where Amy starts explaining how she set up her husband and it’s all voice-over-led and you’ve got the coverage for every single word she said. …

BAXTER: …Just absolutely dessert for an editor to put together because you can move through it at 100 miles an hour and cover huge amounts of ground and it’s incredibly exciting for an audience to watch because it’s constantly changing. There was also a similar thing in “Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” when they were talking about the accident on the bridge and that also probably went through the alphabet three times over in terms of its coverage.

HULLFISH: What did you cut “Girl with the Dragon Tatttoo” on? FCP?

BAXTER: FCP.

HULLFISH: Does Fincher use multiple cameras a lot?

BAXTER: He’s pretty much always two camera.

HULLFISH: Everybody seems to always be two camera nowadays.

BAXTER: Yeah, he’s pretty much always two camera. He will go three or four if a location is hard to get in to or something like that and he’s only got so many “bites at the apple.” But usually it’s two camera.

HULLFISH: Based on what you said about how you set up your selects reels, I’m assuming you don’t use multi-cam?

BAXTER: Oh no. I absolutely use multi-camera. They’ll set up a multi-camera clip and I’ll mark where I want to be at what moment, who I want to look at and I’ll start editing within the multi-cam. Sometimes one of the cameras will only be for a specific moment and everything else is on the other camera. It’s a little more tricky to deal with when the multi-cam is on two different people’s faces. Then they might as well be separate clips.

HULLFISH: How does Fincher usually use the two cameras? On separate people – like crossing over-the-shoulders – or on two different shot sizes or angles of the same person?

BAXTER: It’s very handy when it’s complete opposites on two different actors if all of their dialog is overlapping. Then it’s nice to have the coverage without all the gaps between. But most of the time David will do the two cameras kind of pushing in the same direction, like a 2-shot front-on and the B camera will be a raking 2-shot. And as he works his way in, it will be like that with everything, so I’ll get a close-up front on and a close-up that’s raking. Or my B camera will be from a different actor’s perspective. I find that with David, there’s so much more coverage, and when the scenes are cut together, they feel much more dynamic because you’re not returning to the same angle all the time. If one actor says his line in a front-on angle and then you bounce to the other side of the table to another actor’s line, then when I return to the first actor I can go to the POV angle rather than back to the front-on angle. That’s the difference with Fincher. That’s what the beauty of “Social Network” was. With so much straight-up dialogue, if you’ve got a boardroom and everybody’s talking, we’ve got the perspective of whomever they’re coming off. That’s why you’ve always got the ability to move and it always looks fresh. I see it when I watch movies or TV and that kind of coverage doesn’t exist.

HULLFISH: I wrote a book about 10 years ago in which I interviewed Stephen Nakamura, who color graded Fincher’s “Fight Club” and “Zodiac” and he said that David is very particular about color and very hands on in the grading sessions… kind of obsessed.

BAXTER: Yeah. He talks like a computer about it. He has a laser pointer in a color grading session and he points to specific places that he’s discussing, like at the blacks on the screen and ask, “What are they sitting at? 7? 8? Is the cyan at 6? I don’t think he’s obsessed with it: just accurate as a filmmaker. Color’s just another tool he’s got on his tool-belt. He’s as accurate about color correction as he is about framing as he is about performance. All of the above.

HULLFISH: You mentioned Trent Reznor and the music. So when you were cutting “Gone Girl” or any of your movies they worked on, they presented you with musical choices, score, upfront? So, no temp music?

BAXTER: On the last movie there was no temp music. We brought in Atticus and Trent pretty early in the process. We’d assembled a third or half of the movie. They had a look at everything and then they sent me about 15 tracks and it was quite loose at that point and David and I started laying those in. Then I think we showed it to them again. It’s like all things: first, “here’s a vibe.” And it’s funny how almost every track they sent ended up in the final movie, or a very close version of what they sent us. But as the process goes along, they got a lot more specific. The main body of the music, that came in the first wave of stuff that was supplied was that kind of ethereal, dreamy, everything’s going to be OK, but boils into a sinister rot. I had lots of procedural music. I had lots of adrenaline music. I never had that straight-up horror until they actually saw the scenes. And then when those came they had these titles that pretty much told me precisely where they should go. It’s as if they leave clues for me with the titles. As the movie gets and more finished, the music they provide gets more accurate for what it’s intended to be.

BAXTER: On the last movie there was no temp music. We brought in Atticus and Trent pretty early in the process. We’d assembled a third or half of the movie. They had a look at everything and then they sent me about 15 tracks and it was quite loose at that point and David and I started laying those in. Then I think we showed it to them again. It’s like all things: first, “here’s a vibe.” And it’s funny how almost every track they sent ended up in the final movie, or a very close version of what they sent us. But as the process goes along, they got a lot more specific. The main body of the music, that came in the first wave of stuff that was supplied was that kind of ethereal, dreamy, everything’s going to be OK, but boils into a sinister rot. I had lots of procedural music. I had lots of adrenaline music. I never had that straight-up horror until they actually saw the scenes. And then when those came they had these titles that pretty much told me precisely where they should go. It’s as if they leave clues for me with the titles. As the movie gets and more finished, the music they provide gets more accurate for what it’s intended to be.

HULLFISH: The other interesting thing to me is the relationship between directors and editors. It’s a long-term relationship. Really, we as editors spend more time with the directors than just about anybody. What is it about your relationship with David that you work together so frequently?

BAXTER: I never want to speak for David, but I’m continuously impressed in the most basic way, with how he covers a scene. It’s exciting to work out. It’s exciting to have the kinds of choices I get. It’s challenging. I find that I’m exhausted at the idea of doing a movie with David, but I’m excited more than I’m exhausted. I would hate to miss out. Really, I keep myself available to him. I think that loyalty breeds loyalty.

HULLFISH: Clearly, you’re a very talented editor, but is some of it that he likes to be in the room with you as a person and on a human level?

BAXTER: I don’t ask for too much of David. I try to keep it as a director/editor relationship. A lot of people are asking directors a lot of stuff at all times. I try to keep my side of it down to just the doing. David won’t sit next to me and work. He’ll come in and watch what I’ve done. If I’m unsure of a certain thing I might try it three different ways and he’ll react to what he reacts to and I’ll jump on the one he likes the most. I think he enjoys that I’m not a person he has to wrestle with verbally. That doesn’t mean that I’m a push-over either. My arguing is done in the work that I present, rather than trying to persuade him. David’s not really a person you persuade. You can either convince him through the material or not. So it’s a really simple, clean dynamic. We’ve been working for so long together that we sort of “get” each other. I know how to put him at ease by letting him see selects, by letting him see choices. I take pleasure in making his life a little bit easier.

HULLFISH: There’s some great wisdom there… especially that last line. So, to wrap this up, are you going to keep cutting in Premiere?

HULLFISH: There’s some great wisdom there… especially that last line. So, to wrap this up, are you going to keep cutting in Premiere?

BAXTER: Yeah. You bet. I have a commercial office where we do television commercials in between films. There are ABOUT nine editors there now and I think eight of nine work in Premiere.

HULLFISH: What about the ninth?

BAXTER: He’s on Avid. Not interested in Premiere. He’s never tried it.

HULLFISH: What are the good things and the bad things about Premiere for you and how do you use Premiere? Are you very keyboard driven? Are you in the timeline moving stuff with the mouse?

BAXTER: I move things around with the mouse in the timeline… well, not with a mouse, but with a pen – a stylus. My nickname for myself is the Fisher Price editor. It’s all very basic and simple and it’s a lot of muscle memory. I’ve logged so many hours in Premiere now that it’s just repetition of motion, and if I have to stop and think about what my actions are, I find that a hindrance. So if anything’s more than kind of one or two clicks away, it’s a pain in the neck and I don’t want to have to deal with it. That’s something that I have pushed through with the guys at Premiere: give us simplicity at all times. It has changed a few things for the better. I’m very at ease with Premiere. I like it a lot. In terms of what I’m not happy with is occasionally I’ll get drop outs of sound when I’m playing things back and I still wish – and I will till my dying day – that I could open two projects at once.

BAXTER: I move things around with the mouse in the timeline… well, not with a mouse, but with a pen – a stylus. My nickname for myself is the Fisher Price editor. It’s all very basic and simple and it’s a lot of muscle memory. I’ve logged so many hours in Premiere now that it’s just repetition of motion, and if I have to stop and think about what my actions are, I find that a hindrance. So if anything’s more than kind of one or two clicks away, it’s a pain in the neck and I don’t want to have to deal with it. That’s something that I have pushed through with the guys at Premiere: give us simplicity at all times. It has changed a few things for the better. I’m very at ease with Premiere. I like it a lot. In terms of what I’m not happy with is occasionally I’ll get drop outs of sound when I’m playing things back and I still wish – and I will till my dying day – that I could open two projects at once.

HULLFISH: Why do you want to open two projects at once as a film editor? There’s the film you’re working on and … what else?

BAXTER: Because if you’re doing a movie the size of David’s you can’t have it all in one project, so it gets broken up into reels, and as you’re coming towards the end of the film, I find that in a given day you can be working over the entire length of the whole movie, so I might touch something in reel 1, reel 5, reel 7. And if David pops in to review with me, if I have to talk about one section for two minutes, then close that reel and then open the next one and wait for all that to upload perfectly, and then play that little bit, then close that one and open to the next one. It all takes too long, so I’d like to be able to have two things up at once. One reel that has a copy of everything that I changed that day, so we can review quickly, the other reel of whatever I’m currently working on. I also like to have a separate project that’s just for music that’s independent to the reels and have that constantly open.

HULLFISH: That was a conversation I had with a Premiere product guy a few years ago. I found that long projects in Premiere got very sloggy. And the Premiere guy said, “Well, real editors only cut in reels.” And I said, “OK, but you don’t just want to watch one reel at a time.”

BAXTER: Exactly.

HULLFISH: Was “House of Cards” cut in Premiere as well?

HULLFISH: Was “House of Cards” cut in Premiere as well?

BAXTER: No. Final Cut.

HULLFISH: Did you have the entire episode open in a single project when you cut “House of Cards” or “Synchronicity?”

BAXTER: Yes. But we simplified the projects to only be edit sequences. Then had multiple projects that housed the material. So I always worked with 2 projects open. This prevented Final Cut from crashing from oversized projects, gave me access to the entire show, and the smaller projects with dailies opened and closed quickly.

HULLFISH: Did you have the entire movie in a single project when you cut the other Fincher films on FCP?

BAXTER: We worked in reels that were usually 20 to 30 minutes long.

HULLFISH: I have to say, every Avid project I’ve ever worked in, and I’ve worked on very, very large Avid projects, the whole feature or TV show is all in a single project, so though Avid can’t have two projects open either, it doesn’t need to. But, I have to say that the film I’m working on now in Premiere is all in a single project, but it’s definitely a smaller film than “Gone Girl” was in terms of footage shot. How did you ever watch “Gone Girl” strung out end to end? Export each reel as a QT and edit those together?

HULLFISH: I have to say, every Avid project I’ve ever worked in, and I’ve worked on very, very large Avid projects, the whole feature or TV show is all in a single project, so though Avid can’t have two projects open either, it doesn’t need to. But, I have to say that the film I’m working on now in Premiere is all in a single project, but it’s definitely a smaller film than “Gone Girl” was in terms of footage shot. How did you ever watch “Gone Girl” strung out end to end? Export each reel as a QT and edit those together?

BAXTER: Correct. That also allowed for a safer screenings with less chance of audio dropouts or glitches as the project and media was so simple to play.

HULLFISH: Thank you so much for talking with me about this. This was incredibly interesting.

BAXTER: Great speaking with you. Thank you so much.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series use this link and follow me on Twitter: @stevehullfish

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now