In this episode, I’m talking with the many of the editors of The Discovery Channel’s Deadliest Catch. The team has been nominated almost every single year for over a decade for ACE Eddies – including this year (and won in 2010). They’ve also been nominated for Primetime Emmys almost every year – including this year – and won several years.

Today we’re talking with editors Joe Mikan, ACE, Ben Bulatao, ACE, Rob Butler, ACE, Alexandra Moore, and Isaiah Camp. This is the 16th season for this venerable reality TV series.

All of the editors on Deadliest Catch have worked on the show for multiple years. Alexandra has also worked on Bering Sea Gold. Joe has worked on episodes of Jay Leno’s Garage and Alaska Off-Road Warriors, Isaiah has worked on Billion Dollar Wreck, Ben also worked on Jay Leno’s Garage, and Rob worked on Ice Road Truckers, Badlands, Texas and The Yard before joining the Deadliest Catch team.

This interview is available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about what it takes to do this show. Let’s talk logistics. Is anybody actually in Dutch Harbor, Alaska where the boats are based?

MIKAN: It all starts with capturing all the footage out there in Dutch Harbor. So there are seven boats shooting 13 weeks each and there are two camera operators on every boat running around bravely with their cameras. There are chase boats following, shooting exteriors. There’s a helicopter shooting aerials — along with drones; all kinds of specialty footage from mounted cameras all over the boats to GoPros stuck anywhere they can think of.

There’s crew on land shooting at the dock and all of that footage comes out to about 25,000 hours per season. So the trick then is getting all that footage back to us in Burbank where we post out of. And there are two DITs in Dutch who are QCing the SSD cards and copying that media onto about 30 drives that they’re shipping back to Burbank. Then, when we get those drives, it takes about four days to offload, troubleshoot, ingest, transcode, and distribute to all the editors.

HULLFISH: How are you distributing that? Are you all on one big Nexis?

MOORE: Yeah.

MIKAN: Yeah. We’re on Avid Nexis.

HULLFISH: I’ve got a friend who lives up in Dutch Harbor. And she says that the internet speeds are terrible so I’m assuming that you aren’t getting previews through Aspera or something like that. The shipped drives are the first time you’re seeing media?

MOORE: Yes. They actually take over almost an entire hotel with our crew. They have a whole room of cameras and to transfer the drives and get them back. It’s a big army.

MIKAN: Even just calling somebody out there — there’s like a 10 or 15-second delay in the audio when you’re on the phone with them.

HULLFISH: That’s nuts! But there’s no post up there, other than the DITs?

MOORE: They’ve sent Ben and Rob up there as “film school editors” at the beginning of shooting. What we do is edit overnight what the guys are shooting to kind of show them in real-time what their footage will look like edited. But other than that, there’s now post up in Alaska.

HULLFISH: That’s a really intriguing idea that you’d show the shooters what their footage looks like edited. I’ve talked to shooters about how important it is to understand how their footage is used, so let’s talk about the value of showing someone what their footage looks like when it’s edited.

MOORE: Sometimes it’s months before a shooter sees their footage on-air — or never. So we show them what they shot yesterday in a scene and say, “OK, there is no establishing shot” or “this guy was going up here and you know that would’ve been a great time to follow him and get his take on things.” We put the footage in perspective to the shooters. We shot them what it takes to build a scene, rather than just shooting for weeks on end.

BULATAO: Right. A lot of times they miss just simple things like cutaways because they’re so into the story. Every morning at 8 am the editors would carry our Avid and a monitor and a drive down from our hotel room to the meeting and we’d show it to them.

One of the photographers was really proud of his scene, and I had to explain to him that I need some cutaways. His scene was difficult to edit because I didn’t have any cutaways. He looked shock but then he got it. They tend to forget sometimes that they need to get the extra stuff for us to make the scene look good.

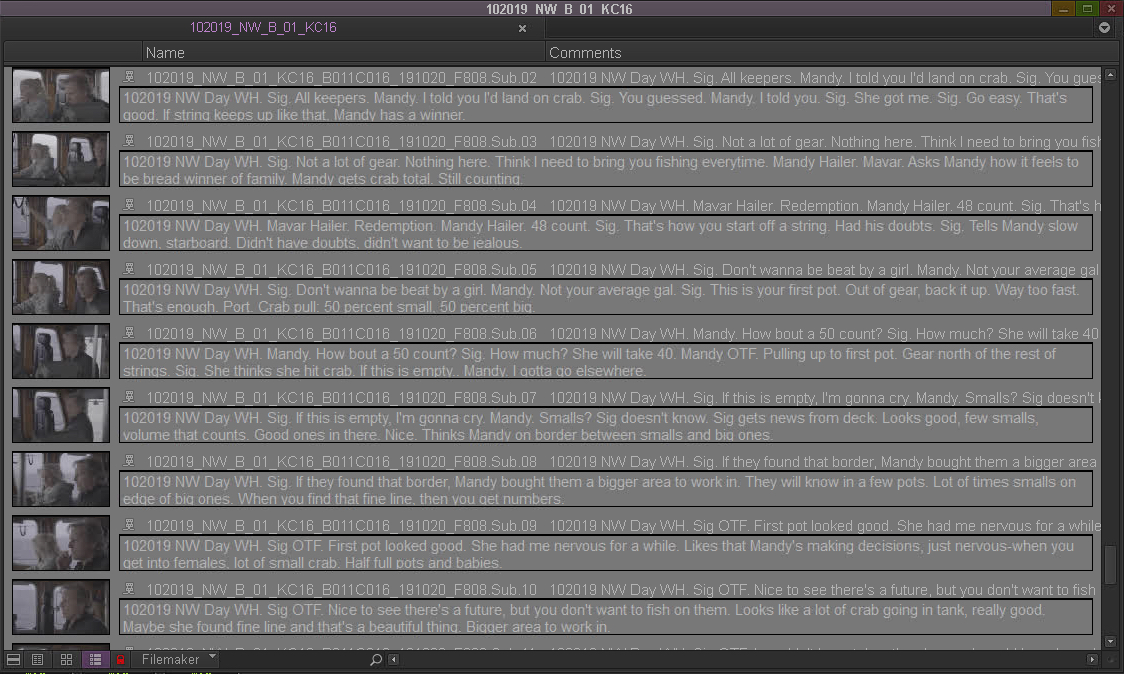

HULLFISH: I love that idea. So you get a bunch of stuff back to a single post facility in Burbank on an Avid Nexis. How do you start organizing that material?

BUTLER: It all starts with a team of loggers — about five loggers each season. Once the footage all gets organized by date — and we tend to group it by boat because they’re all sort of individual shoots on each boat while they’re out at sea. So at least we can kind of group it that way.

Then the loggers just watch all the stuff that the producers and shooters on the boats shoot. Not all the deck cam stuff, but mainly just the handheld stuff that the producers and shooters are on deck and in the wheelhouse.

They make very detailed notes. They have a coding system of who is talking and storylines that we’re covering and we rely on those when we’re building the initial outlines and all season long. If it weren’t for those logs I don’t think we could access all the great material in that footage. It’s great for 1) figuring out what we have what we captured and 2) to go back to later and find details that we might have missed in the first pass.

Then a team of associate producers basically make long string-outs of the footage and try to figure out — based on story notes that the producers will send back from the field — they’ll give us a heads-up on particular dates and times that major events happened or storylines that we’re trying to follow throughout the season or are developing, and then they start assembling a rough pass of the major events in the season.

That’s when the executive producers — Johnny Beechler and Arom Starr-Paul — come in and they start figuring out: what are the ideas this season that we’re going to follow? They start organizing them into piles. The whole office is covered by different colored note cards. Each card is what happened on this day for every boat. All seven boats.

They start to just roughly figure out: “Let’s thematically shape an episode around this idea.” And then they send that to a team — which is a story producer and an editor — and they work for six weeks to basically just build the stories and refine what’s there and figure out what’s missing and what they have to go back into the footage to find and develop.

But the answer is always in the footage. The cameras roll all the time. There are no breaks. It’s not like they go home and wrap at night. There’s always footage. There’s always something in there. So no matter what you’re following, you can always go back and find something else that supports the idea that you’re showing. And so that’s basically how the shows get built.

And then there’s a refinement process at the end. We have what’s called a lock bay where we address the final network notes and also make all the episodes connect and make sure the stories are connecting from one episode to another.

HULLFISH: On a day-to-day basis, are most days about constructing a specific scene, then you build those scenes into something greater? When you come in on a day what’s the plan?

MIKAN: I think what’s really cool on an unscripted show like Deadliest Catch is that the editors are involved with crafting the story from the very beginning. It’s like an investigation. You’re trying to uncover story from all this material — from the 25,000 hours — and you really need a game plan to go about that. So when we start the episode we need to figure out what the premise is for the overall episode, and then from there, every scene needs to be somehow attached to that premise.

Then we’re trying to clarify the motivation and the stakes and the strategy of the characters in the boats within that in building out the drama.

For a specific example on how that breaks down, the premiere episode this year — the premise — was that Russia is cracking down on illegal crab and limiting quotas, so the first boats back to dock — Russian or Alaskan — are gonna make the most money, so it’s essentially an international face-off between the American and Russian fleets. So that would be our premise. And then the motivation for everyone is they want to get back first to make the most money. So the strategy would be how each boat wants to go about doing that.

For the Cornelia Marie, for example, they basically did a million dollar rehab in the off-season and turned their boat into a hot rod for faster speed and maneuverability. So that’s their strategy and their stakes are that they’re now a million dollars in debt, so they have to get back first and land on crab so that they don’t go broke.

The drama comes in when they go out to sea and their engine fails immediately and they have to turn back around so you can see how a story arc starts to take shape with that kind of strategy. Then in the cutting room, we’ll work with the story producers to power through the footage and find moments that are going to serve that story and we’ll go through scene by scene trying to build that out.

MOORE: We’ll come in and have a rough outline — paper or string-out. Each producer works differently. We go through and edit, working beat-by-beat with the producers to figure out if we have what we need. We always do! That’s the thing with so much footage, is it’s always there. It’s just there are so many levels of filtration to find it.

HULLFISH: So on such a giant episode as that premiere episode I’m assuming it’s not just one editor doing that whole show.

MIKAN: No. For a standard hourlong episode, you would have one editor cutting through fine cut for about six weeks until we hand it off to Rob or Isaiah to do their finishing magic on it. For a two-hour episode, like the premiere, we split it up by boat, so the same editors can track the same boats over the entire 90 minutes.

There are seven boats, so Ben and I each took three and then we split up the last one.

HULLFISH: So two editors on one two-hour episode.

MIKAN: Right.

BUTLER: We work as a team. There are seven editors total and we have junior editors and assistant editors. This show only gets done because of the team so even though not everybody is credited as a full editor everybody has an influence on all the shows. Maybe one scene gets cut or refined by somebody or a style or concept that somebody creates gets woven into another episode. So we’re always next to each other, always talking to each other and helping each other out on episodes.

Some episodes will have five editors credited because everybody will contribute when needed.

HULLFISH: When I was at the Oprah Winfrey Show I loved having a team of other editors around me. Can you talk about the benefits of being a part of a team?

MOORE: I started on Catch eight years ago and everything a lot of what I’ve learned is from these guys — whether it’s watching their cuts or going in and asking specific questions. Ben will run in and say, “I found some new music. You should totally check this out.” Or “Has anyone seen this guy?” There are so many deckhands and so much story we’re dealing with that sometimes in three episodes you haven’t worked with this boat.

So just to be able to talk to editors and ask, “What has this boat been like when you’ve been cutting it?” They can give you some tips and that really helps.

BUTLER: It opens up your mind when different editors come in. Isaiah joined the show about four or five years ago. He brings his own unique style to his cold opens and montages. Everybody here and all the editors on the team have their own unique style.

Part of it is seeing, “What did he or she do? That’s interesting. Maybe I could try — not copy that — but try to answer that in my own way.” Since these scenes also tend to live in the same episode — like if Joe and Ben both cut scenes for episode one, they need to not feel like they’re in completely different spaces. They need to meet somewhere, but there is that “looking at what the other person did” to raise your game a little bit and it’s a fun challenge.

BULATAO: I would look at Isaiah’s cuts a lot because he does things with music — he actually composes the music. He takes stems from different music cues. I felt like, “I’ve got to learn this!” I’m looking at his stuff and I’m getting inspired. Then I start to do that kind of stuff too.

I’ve been doing that more this season — just by looking at Isaiah because when Isaiah came in four years ago our style just went up really high just because he brought something different to our show.

I’ve been doing that more this season — just by looking at Isaiah because when Isaiah came in four years ago our style just went up really high just because he brought something different to our show.

MOORE: Yeah. New blood always helps.

HULLFISH: How are you collaborating with producers you’re working with and the story producers? Story editors?

BUTLER: Story producers. Yes.

MIKAN: Yeah. They’re our secret weapons, definitely. We could not do this show without them and they work right next to us. We pair off in teams of two and they’re sitting right by us, bouncing ideas off each other, helping us mine for footage.

They’re also writing the lines of narration for Mike Rowe which we use to help clarify and add context to all the scenes. For example, if a crew pulls up a full pot of crab, but has to dump them all back because they’re female, Mike Rowe would say — through narration — by a line written by a story producer, that it’s illegal to fish the females because they’re repopulating the species.

That’s something so obvious to the crew that they might not say it out loud at that moment, so the story producers will write lines for any important information like that, that the viewer might need to help track this story.

HULLFISH: I saw a bunch of nice animation. Are you or the story producers saying I need a graphic to clarify some geography?

MOORE: Yeah. We have a graphics team but when you need graphics it’s usually because you can’t do it through writing or through the footage itself, so we really rely on that for especially mechanical location, map graphics and stuff like that. There’s just no other way to do it sometimes.

MOORE: Yeah. We have a graphics team but when you need graphics it’s usually because you can’t do it through writing or through the footage itself, so we really rely on that for especially mechanical location, map graphics and stuff like that. There’s just no other way to do it sometimes.

HULLFISH: So you’re just temping that stuff in with like a text card or something until it shows up?

MOORE: Yeah.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about structure. How are the episodes getting structured from the individual scenes or story beats?

BUTLER: I think it starts with the executive producers when they’re looking at all the cards on the wall — kind of like that movie, A Beautiful Mind — so you inherently shape it into something you think you can follow. And of course, that changes a lot over time.

We do about 24 hours of content a season. We treat it almost like a one hour drama. We’re telling a documentary but basically with one-hour drama narrative techniques, so we still follow a lot of the same rules I think that one-hour scripted shows have — an A story, a B story, and a C story.

So we try to look at it that way. Like, what’s the main story for the episode? What are their goals? What are the obstacles they face? How did they handle them? And then lesser stories that then all weave together and follow the same theme.

They tend to get grouped by theme but we also vary the emphasis depending on who has the most action and who transforms the most.

They tend to get grouped by theme but we also vary the emphasis depending on who has the most action and who transforms the most.

On a normal one-hour episode, we don’t follow too many boats just to make it easier to follow for the audience, because we like to check in with the same boat two or three times over the course of the hour, but for a big episode like episode one or there’s a midseason show where — tragically — a boat in the fleet is lost. If there’s a big moment in the series where everybody is affected, then it warrants to pop around and check in on all the boats and seeing how they’re reacting and changing to the situation.

For the most part, we just try to follow the simple structure that editors have been doing in narrative structure for years.

HULLFISH: On a day-to-day basis are you attacking things just by boat to get started? On a feature or scripted drama, you have to think in terms of the scene first is that what you’re doing?

MOORE: Yeah. When you work with a boat, the thing I always ask my story producer is: “Where did we last see them and where do we want them to go?” That’s kind of my story arc for that boat. So if I’m working on a scene and there’s a bunch of stuff that really isn’t going to serve us, we just don’t have real estate in the show for anything not super compelling, so it’s: “Is this going to serve the story?”

When you’re working on one scene I just try to keep that in mind. But yeah, it’s scene-by-scene for a couple of weeks and then you look at the whole thing and ask, “Is this working?”.

MIKAN: I think it’s easiest to go boat by boat, so you cut the four scenes for one boat and then move on to the next boat and then figure out how to structure them all within the episode in the most compelling way possible.

MIKAN: I think it’s easiest to go boat by boat, so you cut the four scenes for one boat and then move on to the next boat and then figure out how to structure them all within the episode in the most compelling way possible.

One of the biggest challenges is compressing the time — because we’re going from 25,000 hours down to the 24 hours of content.

In a way, editing can be the art of removal. You’re just chiseling away. I think it was Michelangelo — they asked him how he made the David — and he said “It was always in there under the marble block, I just had to chip away the extra material.” So we’re basically cutting away 24,976 hours so that the best 24 remain and can tell the most accurate and compelling story.

BUTLER: There are about 3000 hours of logged footage and then all the rest of that is really just surveillance-type cameras running. We have four on each boat running high up on the mast, on the deck, in the wheelhouse so that we don’t miss moments. We have a dedicated deck cam logger. That’s all they do. They chase down events that we want to see from different angles or things our producers missed on deck.

MIKAN: We’ve tailored the technology to not miss any story out there at sea because the human camera operators eventually set their cameras down or sometimes they get seasick or just have to go to sleep at night. So those mounted cameras are rolling all the time so we don’t miss anything. Things happen quickly and unexpectedly out there at sea.

HULLFISH: So you have organization at the story-beat level and then you have all these fantastic like color shots of propellers spinning and eagles sitting in nests.

MOORE: The fun stuff!

HULLFISH: The fun stuff. How does all the fun stuff get organized? And how concerned are you that the footage is from the same day or around the same time?

BUTLER: There are two ways to look at it. We’re basically telling an authentic story over the course of several weeks, so there is a lot of compression going into the storytelling. When we’re in a real-time verite moment, and in that case we stick to the footage in that area and the surrounding area to tell what’s live and what’s happening in that moment.

But there’s also other sections of the show that demand pacing. So there might be a fishing string where it takes them eight hours to haul a string that’s either good or bad and that’s where we — as editors — get to have fun and create that time compression and expansion by searching around and pulling the best b-roll shots from within that range.

There’s typically not much leeway — because the seasons looked pretty different — the winter season is icy and a different species of crab. Halfway through the fall, they switch species sometimes, so you have a little bit of a range to play with. You can pull a shot that might be a little bit more sunny from a couple days earlier, but you can’t use that shot again in the middle of the snowy winter.

There’s typically not much leeway — because the seasons looked pretty different — the winter season is icy and a different species of crab. Halfway through the fall, they switch species sometimes, so you have a little bit of a range to play with. You can pull a shot that might be a little bit more sunny from a couple days earlier, but you can’t use that shot again in the middle of the snowy winter.

So we do take a little liberty in creating the stylistic connecting montages and that’s where we get to have fun with the music editing and pulling from different areas but for the most part, it needs to stay within a certain range.

MOORE: And organization-wise, I think we each work pretty differently. I wouldn’t be able to go into any other editor’s projects and find any of the good stuff. Each of us has bins and bins of our secret favorites.

BULATAO: And I spend half-a-day at least pulling footage from all of these different places just so I can build up my palette — kind of like a painter’s palette — before I can start any type of edit.

I pull every tape from that day within our days and I would run through and just scroll through and do locators of shots I could possibly use. Then I just start editing away toward the end of the day. It usually takes about a day-and-a-half to do a beat.

HULLFISH: Do you start with a radio cut to begin with, or are you assembling something more elegant than a radio cut from the very beginning?

BULATAO: When I edit, I always want to sell whatever I’m trying to show our EPs and so I always edit like it’s going to be a fine cut. I just try to make it as full as possible with great music edits, sound effects.

I want really good wind or wave sounds because sometimes the audio — when you’re getting it off the camera — it sounds over-modulated, so you need to supplement it with a nice wave sound that we have in our sound effects bin. I just try to sell it as much as possible as if it were a fine cut even though I’m just trying to get to a rough cut.

MOORE: Even though we’re getting radio cuts from the producers, I think the expectation for the editors is to deliver full sound effects and music. It’s not at all just a radio cut.

BULATAO: Also, too, I don’t want to leave too much work for the finish team. That’s my motivation when I do these rough cuts.

HULLFISH: I understand that you wouldn’t LEAVE a scene like that, I’m just talking about the process. So you’re fleshing it out as you go? Not laying out the beats and THEN fleshing them out after you have a skeleton of sound bites or some rough verite moments? Or does everyone have a different technique?

MOORE: The story producers really go through first and do the radio cuts of what they want and tell us where they want the VO to go and then we go from there. Sometimes it works the way that they pictured, but usually, it takes a lot more addition.

CAMP: Because of the nature of the show and it’s so grounded in the documentary foundation — a traditional radio cut would be difficult to try and apply scene-by-scene because so much of the actual verite is being used in the development of how that scene is coming together.

For instance, with Mandy doing the wet storage, it happened how it happened and we’re trying to depict that in the most organic way possible of how it happened. Even when you come along with voiceover, later on, that’s more to just help that clarity about some of the finer points of why what she did was a problem.

I would definitely say that just because of the nature of the show, a traditional radio cut is not where you would start.

HULLFISH: I really love the pacing of the episodes I watched. It’s opened up. It breathes. The voiceover is nicely condensed. Let’s talk about how to keep a unified sense of pacing across 10 different editors. It does feel like there’s a Deadliest Catch pace.

MIKAN: It’s really fun because we are allowed to let things breathe and play out on this show. I’ve been on other shows where you get the note to make an edit because there hasn’t been an edit in a while. People get uncomfortable and that’s the worst reason you could possibly make an edit!

On this show, we’re encouraged to let things breathe because it adds to the realism of the show. And it also makes the faster-paced moments work well too because you get this rhythm back and forth and sometimes you need those breaths to just slow down and settle into the atmosphere. That atmosphere helps us build tension and tone.

On this show, we’re encouraged to let things breathe because it adds to the realism of the show. And it also makes the faster-paced moments work well too because you get this rhythm back and forth and sometimes you need those breaths to just slow down and settle into the atmosphere. That atmosphere helps us build tension and tone.

BUTLER: Because this is a show that’s been on for 16 years we’ve all kind of grown up in this show. We’ve all been working together for years and years and came onto the show in various stages, but there are great people that started the show and helped develop it. We follow in the footsteps of people like Josh Earl — who was the supervising editor for many years.

They started a style and then we just learn it by watching and learning from them and then hopefully we try to change it a little bit on our own and then as we bring in new people they continue to evolve it, but that is the draw. As an editor, to have a chance to create atmosphere is probably one of the biggest things you can do. That’s your time to add your subliminal voice in there. Time for you to do your thing.

The atmosphere is one of the major draws to this show. It’s all the creaks. It’s the moans of the boat, the metal, the machinery, the waves.

A 20-foot wave rolling past the boat shouldn’t be something that you step om with a voiceover line. You don’t want to diminish what’s actually happening in the scene by just having bites and VO all the time.

MOORE: And “paragraphing” is big too. We are jamming a lot of information into these scenes so to have those moments in between to say, “OK, now that you’ve learned about THAT, now something else is going to happen.” I think for the audience a cue that they’re different story paragraphs through editing.

MIKAN: And we’ve all been working with each other for years. Some of us for well over a decade, so I think our styles — while they are a little different — they also complement each other really well.

Then Rob and Isaiah in the finishing bay — they will do a pass to conform all the shows, so they do have the same feel throughout.

HULLFISH: What do you mean by “paragraphing?” I can kind of guess what you mean, but how might that be used in a note? Or, if I’m the new guy on the team and someone says, “You should have paragraphed that!” How do you explain that concept to me?

BUTLER: It’s really just being clear about what you’re focusing on at what point in time and not trying to muddy the waters. It’s maybe a little pretentious to say but, as editors, we all kind of want to be directors intellectually with the project we’re working on and we’re basically controlling where the audience is supposed to look at what time, and so we have to be very clear and precise in our language about what idea is being expressed at one time.

In editing It’s all about paragraphing. It’s all about making sure that you’re making a strong point here and then you’re either countering that point or shifting it and making the transition to the next point smooth and create a level of excitement.

MOORE: It’s done a lot musically I think. Some notes would be: if you have the same cue, but two major ideas, it’s going to feel like we’re trying to connect them when you might not be. So you’d want to sting something out — maybe go to a wide shot and let something settle before introducing a new idea, because you can get whiplash on those boats there’s so much going on.

CAMP: I would say a classic example of that would be something that’s very traditionally Catch which is the first pot moment when a boat is coming up on their string for the first time in the show and you’re about to find out if they have any crab in it or not. So the paragraph preceding would be resetting where they are, what their strategy has been, why they think there might be crab there.

You have all that information and then you would start a new paragraph for when they’re going to throw that first hook and then you’re starting to try and build the anticipation of whether or not there’s crab in there.

HULLFISH: What are the tricks to building that anticipation? The show almost has a horror movie vibe at times. There’s a sense of dread or — “anticipation” is the best word I think of. How do you build that sense from pieces of film and sound?

BULATAO: I remember Thom Beers — who created the show — just stuck it in our minds that this is like a slot machine. You pull the lever and then you’re just watching and you don’t know what’s going to come up.

So we’re building up — with a really beautiful hook toss — then anticipation of faces looking and we’re not giving it away right away, we’re just building up that anticipation. And right before the pot comes up, you bring out the music, because that makes you wonder, “OK what’s happening?”

Then you have a shot of the captain looking over too. He may say something and then suddenly the pot will break the water, come over, and whatever it is — good or bad — and then you’re cutting in something to match the emotion.

Then you have a shot of the captain looking over too. He may say something and then suddenly the pot will break the water, come over, and whatever it is — good or bad — and then you’re cutting in something to match the emotion.

MIKAN: I just love the term “like a horror movie.” I think that fits it so well because we are trying to drag out the tension as long as possible but not too long that it gets boring.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about the importance of sound and how sound works in story and building anticipation — building the world.

MIKAN: Sound design is extremely important on a show like this and we use it to create atmosphere and tension and for pacing and we always like to use the organic in-scene sounds whenever possible. Those boat noises, the creaking from all the weight, and the waves crashing against the bow.

A lot of times the nat sound is unusable due to conditions or mikes fail because it gets so cold and icy out there. And in that case, we will use sound effects and walla. You can easily fill up your timeline trying to create the sense of realism of what it actually sounds like out there.

It can be a little counter-intuitive to use sound effects to make it sound real but if you’re getting in shots and picture where the audio is unusable and it’s just flat, then that’s unreal. That’s not what it sounds like out there. So our goal is to try and add texture and bring the scene to life in a way that it actually sounds like if you were out there on the boat.

BUTLER: With tension — it’s a dangerous show — part of the draw is that these guys are trying to accomplish this amazing task under these horrendous situations and we’re always drawing on that tension. Most of the time it’s life or death or someone’s going to suffer a major injury. So it is a super high-stakes profession and we try to let the audience feel that.

BUTLER: With tension — it’s a dangerous show — part of the draw is that these guys are trying to accomplish this amazing task under these horrendous situations and we’re always drawing on that tension. Most of the time it’s life or death or someone’s going to suffer a major injury. So it is a super high-stakes profession and we try to let the audience feel that.

We like to mix it up. It’s like that old Hitchcock example: the bomb on the bus. If a wave just hit the boat, that wouldn’t be as exciting as knowing ahead of time that there are 30-foot prowlers out there and “you’d better be careful on the deck guys” so you build the tension until the wave hits. But it’s great to mix it up and do it different ways.

Sometimes you build the tension — and this is really just what’s going on in real life because there are a thousand dangers out there — so it could be one thing that you’re building the tension to that the captain is paying attention to at that moment. It’s something as simple as the fact that the guys on deck are super-tired and they’re getting on each other’s nerves and — as happens quite a bit — they might be breaking out into a fistfight really soon. That’s where you think the tension is building to, but all of a sudden there’s an engine fire and now our attention has shifted down there.

So there are lots of ways to craft where we’re focusing the tension — where we’re going — and then turn it suddenly if we have to.

MOORE: And there are certain times that we don’t need music because of the sound effects. For example, the listing scene. The boat’s rocking back and forth in the bow’s full of water and just the creaking and sloshing and seeing all the water running is almost more ominous than a cue would be. It starts to get a rhythm and drive that tension even more of: “How many times can this boat do this before it just goes right over?” We can use sound effects like that to be just as scary as a 20-foot wave.

MOORE: And there are certain times that we don’t need music because of the sound effects. For example, the listing scene. The boat’s rocking back and forth in the bow’s full of water and just the creaking and sloshing and seeing all the water running is almost more ominous than a cue would be. It starts to get a rhythm and drive that tension even more of: “How many times can this boat do this before it just goes right over?” We can use sound effects like that to be just as scary as a 20-foot wave.

HULLFISH: What are some of the reasons or places to break or jump from one story to another?

MOORE: Jokes. If a captain says something maybe a little salty. Those can be good “outs.”.

BUTLER: It’s a fine balance between crafting a nice atmospheric transition that gives you a chance to breathe and cleanse the palette and absorb the atmosphere, but at the same time you don’t want to lose the audience and make them think, “OK. That story is over. Time to change the channel.”

There is always that idea to keep people engaged and thrust them into the next scene. There’s time to do both. If it was a really tense scene and somebody just survived something and it just needs a moment to unwind, we will put that little pause in pace in there before we cut to the next boat. But other times you just want to thrust right into the next scene and get the next scene going.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about the act structure and going out of breaks on cliffhangers. When you go out on a cliffhanger and then you come back from the break, you always repeat or replay that moment. Do you try to replay it identically to the pre-break cliffhanger or change it up with another angle or a section of the sound bite?

MOORE: As little as possible.

MIKAN: I think you want to change as little as possible, just so the viewer doesn’t think we’re manipulating it in any way — even though there are multiple cameras covering it. Unless you have a breakdown or an injury or something like that, that you can see happen from all the different angles, then it can kind of turn into a sports replay: just to get to experience it from the multiple different angles.

BUTLER: The cliffhangers are a bit of a trope of this genre. I’m kind of happy that we’re still in commercial television. I can imagine someday when it’s just all streaming and people wonder why you would need to keep a viewer over a commercial break.

So it’s dictated by our medium. We’re working within those boundaries. The thing we want to avoid is not just crying wolf every time and setting up: “Watch out! This really dangerous thing is going to happen!” And you come back and then it’s like, “Oh. Everything’s fine Let’s go back to work.”

The way we craft the stories we try to make sure that those events have consequences or change the course of action — make the captain make a different decision and send the plot in a different direction. So that’s the one thing we try to pay a lot of attention to with our cliffhangers is that they’re not just gratuitous to keep you over the break. This is a key moment in the trajectory of their story for this episode.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about score. Are you temping with anything or what are you doing for music?

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about score. Are you temping with anything or what are you doing for music?

MIKAN: It is the editors that are choosing the cues to use and how to use them and that is what makes it into the final cut of the show. We’re not just laying in temp score that’s going to get scored over at the end.

We have a composer who is amazing. His name’s Didier Rachou. He’s created thousands of cues for us that span 16 seasons of the show and the cues are separated into stems by instrument. So there’s really a lot of freedom to play around. We like to use the music as film score, not just background music, but to create pacing and add emphasis to moments of importance.

BULATAO: He gives us about 50 to 80 cues per season, but with 20 to 30 alternate versions. So that’s about 1500 mixes. I was talking to him about it the other day. He’s given us so many cues to work with.

Sometimes he’ll score it, too, if we want. If we have a special request, he’ll score it. He’s great.

MOORE: He’s really great. I was working on a scene and we wanted an Ocean’s 11 feel — because it was a prank. He’s a big fan of the show too. I think you can feel that when you hear the show and when you hear his cues that he’s a pro.

CAMP: He’s really an extraordinary talent for sure.

BULATAO: We’ve gotten close throughout the years because we happened to be in Dutch Harbor at the same time. I didn’t know he was a composer until we both got off the plane. We were both fans of the show. We went to each boat and visited everyone.

Didier was collecting sounds — natural sounds from the whole island. Like hitting World War II bunker doors with mallets. Just creating stuff so he can add it into his music.

This year — because there’s a lot of Russian storylines — there’s a lot of large-scale orchestral cues with choir mixed in with electronic elements — kind of like Stranger Things. It’s a modern way of showing tension, instead of just drones. Didier is on fire this year, for sure.

CAMP: It’s really impressive because if you listen to the music that he was making half-a-decade ago even, it was great. He’s been able to evolve his music as the show has continued to evolve.

I’m newer to the show than a lot of these other guys, but that makes it more impressive to me how the show continues to evolve and build and maintain this really high integrity and high quality — which makes it a pleasure to work on. And the music is a big part of that, too.

What Didier has been able to do — this year in particular — I’ve just been blown away with how he’s taken some ideas we’ve thrown at him tonally and things we might want to try and he’s just made some really incredible music that has been a signature for this season in particular.

MOORE: With the Russian influence — but not being too heavy-handed with it.

HULLFISH: Tell me how you use the stems. How is that different from just using a composed full score?

CAMP: This is one way in which Didier is extremely generous. I don’t know that all composers would be as amenable to editors chopping up his stuff and moving it around, but he loves it and he really likes how we do that and he gives us the tools to do it.

That also goes back to something Joe was saying about it being more like a film score. When you’re able to use different pieces of the music it allows you to sustain that music and have it build in a way that complements the scene. Obviously, in an ideal world, he could score to picture but that’s just not possible very often. He does it in special situations, but it’s usually not possible with our schedule and the amount of material we have to get through and the cuts that get out the door.

So what he’s done by giving us these stems is allowed us to build the music custom-made for these scenes in a way that complements the scene better.

Maybe you start with percussion and then you start bringing in the strings as the scene starts to build out. One thing that I’ve noticed over my time working in this genre is that the paragraphs that we were talking about earlier can be really short. I’ve had people tell me — when I was coming up through the ranks — you can’t have the same music cue on for more than 45 seconds to a minute or it’s been on too long.

But when you get the kind of music that Didier gives us, you can use a cue for a minute-and-a-half or two minutes, because you’re using different pieces of it and it’s evolving throughout that scene and accompanying that scene in a way that gives that feel of immersion, like a film would give you.

HULLFISH: So if you understand music structure, having the stems would allow you to extend or shorten a cue without ruining the structure. For example, a phrase of music might be in the piano, but if you’re only using the strings you wouldn’t have to worry about a strange break in the music phrasing.

CAMP: Absolutely.

BUTLER: It seems like — more often than not — editors tend to have been musicians at one point in their life. I was in the marching band. I played trombone. I don’t still do that today, but learning how to play an instrument and learning how to count in time and play with a group, that’s the tool you take with you as an editor forever.

You know how to read a musical stem and know not to break it in the middle of a phrase. It really informs your cutting to just have a basic foundation of music.

CAMP: Absolutely. Editors work differently, right? Some start with the music some start without. I prefer to start without because I feel like, depending on the pacing of the scene, it’s gonna be a different music meter. A 4/4 scene — kind of deliberate. If it’s gonna be more tense it’s going to have a faster tempo.

There’s a visual rhythm that can really tie in with that music.

HULLFISH: I loved the Russia montage at the beginning of the season. Rob, I understand you put that together?

BUTLER: That was a fun one to put together. There’s a long-standing tradition — because we’re neighbors with Russia up there. We’re actually doing a separate special about Russia this year and how our Bering Sea captains — back in the 90s — would go to Russia and fish.

So — long story short — one of our characters — in between King and opilio (snow crab) season — Wild Bill — he actually goes to Russia. Because of the tie in with what was going on this season globally and just that it’s an interesting story that we haven’t seen before of a captain going to Russia seeking employment — that was worthy of starting the show with.

The trick was that it’s not linear, because it happens after King season before opilio season, but sometimes necessity is the mother of invention. We wanted to lead with that but then, of course, we needed to find a way to get back into the present time, so we made that little reverse montage to get back to October. So we jumped from December to October and then later we start showing flash-forwards from January.

So as an editor you’re always trying to make sure you’re clear. Obviously you want atmosphere and impact — all are important — but I also want to make sure the audience understands what I’m saying.

In that case, it was a fun one just to say, “Here’s the problem: I want to lead in the future jump back to the past. What’s a fun way to do that?”.

HULLFISH: One thing I was trying to figure out with that opening montage was that it didn’t seem to come back in other episodes I watched. Was that just a structural thing of showing a future event that will eventually be paid off?

BUTLER: A lot of us are fans of Breaking Bad. We’re influenced by our heroes. That was a technique that they did to amazing effect. We were in a position where we know we have this big event that happens midseason — it’s not going to affect the outcome of this particular episode — but we just thought it’d be a fun way to start the episode way in the future and then figure out “how did we get to this point?” Breaking Bad is a classic example of that.

Sometimes we just have to pick something that we love and aspire to do our own take on it.

HULLFISH: There’s also a great slowed-down Bon Jovi cover by a female singer that gets used as part of a music montage. Was that edited to the original piece of music slowed down or did you have that final cover to do the editing?

MIKAN: It was the first storm episode of the season and right away our showrunner, Arom Starr-Paul, came up to me and said, “I have a song for you to use for this.” He wanted to use Dead or Alive, but with a female vocalist and a slowed-down version of the song.

April Kelly is the name of the singer that he commissioned to do that and she delivered this amazingly haunting, beautiful, slowed-down version of the cue.

For every episode’s cold open we want to do something a little bit different, and since this was a storm episode — which I think are always the most fun to cut because you get to play the storm in the Bering Sea as like a hostile antagonist that’s just pummeling the boats with gale-force winds and 50-foot waves and knocking them around like toy boats in the bathtub.

Whenever we pick a piece of featured music, we want the lyrics to serve the story that we’re telling and also for the tone to fit. He knew that the rock version wasn’t gonna really match the tone, so I think he wanted to slow it down and make it more haunting, but the lyrics were perfect.

The danger is so genuine in those storms and the captains are figuring out how far to push their crews without anyone getting hurt or anything breaking. People do get hurt. Things always break and the stakes are life and death.

We’re using that cue in the cold open. We’re hearing those lyrics weave in and out while we’re seeing the epic visuals of this storm, and it just fit perfectly.

HULLFISH: Did you have that as a piece of music as it was recorded to cut the scene with?

MIKAN: It came in pretty quick and I think we held off on cutting until the cue was in because we knew it was going to play such a big role in creating that.

HULLFISH: That was a pretty awesome bespoke piece of music. It fit perfectly.

MIKAN: It’s so fun. We have a feature music budget for this show and our showrunner, Arom Starr-Paul, is always encouraging us to dip into our personal music libraries and try and find music that works, and if it fits the scene and the character that’s involved they’ll try and license it.

For the premiere episode, we were also able to get The Passenger by Iggy Pop, which I thought was pretty cool.

HULLFISH: That’s a very trailer-y idea — to use a massively altered pop song.

Let’s get back to structure. Did the structure change much? Or once the story editors lock in the structure, you’re done?

BUTLER: It evolved all the time. All the way through the whole eight weeks of edit. You have the initial idea of what the footage is and then you uncover some new piece of footage that shows what actually happened.

You’re always trying to search to make sure you have the real truth of what happened and then also things that are more exciting — funny moments that we find. It evolves all the way through.

What’s interesting about the way we work with the story producers is that they’re basically editors too. They’re on an Avid. So we’re basically sitting next to each other on Avids and they’re cutting together different sound bite sequences and handing them over to us and we’re just working in tandem all the way up until the deadline — until we have to lock it, the show can and will change.

MIKAN: One of the techniques that we like to use is to kind of “reverse-engineer” the story arcs once we have them. So when the episodes are laid out and we know from the material what’s going to happen at the end, we can go back and start planting clues to foreshadow or even misdirect at the beginning or even re-shuffle scenes. Whatever makes the story more compelling or dramatic.

MOORE: We’re still at the mercy of the fact that this is an industry and we need to represent certain things like they need soak time on their pots, so you might have to have a scene where they’re setting because later they’re gonna be hauling. Maybe not enough time goes by or there’s a day-to-night on a different boat. So there’s a lot of moving pieces to make sure that we are telling it how it happened.

MIKAN: And sometimes the scene just ends up really well done. Like in the premiere, Ben cut this scene with Harley — who’s the guy that uses the deceptive tactics — that scene came out so good that I think it ended up getting moved up to the front of the show.

HULLFISH: So that’s interesting, that when you realize something is working so well, you’d move it to the beginning.

MOORE: Or let’s END on this. This is a great ending. We were gonna go someplace else but now we don’t need to.

HULLFISH: In one of the episodes I got a sense that it was being set up — like a captain early in the episode saying, “Somewhere out there, there’s a wave with our name on it!” By having that quote early, it’s always in the back the audience’s mind each time it shows a big wave coming at the boat later in the episode.

MIKAN: That’s a great example of reverse-engineering those story arcs.

In the cold open that we were just talking about we ended with a bite from Captain Jake where he says, “When the weather’s this bad the rescue helicopters can’t fly and you’re on your own.” That’s doing foreshadowing because Jake does get in a life-or-death situation with multiple mechanical breakdowns and we know from that bite early on that there’s no help coming and these guys are going to have to figure out how to get out of it on their own.

HULLFISH: With music montages, do you plan where those go in the episode based on the macro pacing of an episode? For example, “We could use a montage around here to get a bump of energy” or something like that.

BUTLER: There is a basic process to the show that we have to stick to. Fundamentally, it’s a fishing sports show and we can’t skip too many steps. We have to see them try to fish in one spot. It’s a failure. They have to pick up their pots, move 180 pots, stack them, drive them to a new location, set them, haul them.

All that takes three days, so the fun part about the show is that we try not to skimp on the details of the actual fishing because part of our audience really enjoys that. They like to see all that process and it’s important. Sometimes it’s just fun to watch crab coming over the rail.

That’s another chance for the editor to shine — “Alright! We need to create a little montage to get from point A to Point B.” But also just so we can revel in a moment and appreciate the process and the beauty of what we’re looking at.

HULLFISH: To jump back to something I heard earlier: the production is sending another boat out into that weather just to shoot the other boats?

MOORE: Yep. It’s a crab boat.

MIKAN: Same size as those crab boats. It’s a huge boat and they have RED cameras on them and they go out into the storm’s following along.

BUTLER: They’re out there all the time and you might get lucky and just have the real footage that day from the other angle on the chase boat, which is amazing as an editor to have that real footage in real-time.

BUTLER: They’re out there all the time and you might get lucky and just have the real footage that day from the other angle on the chase boat, which is amazing as an editor to have that real footage in real-time.

This season there’s actually a treacherous moment midseason where one of our boats gets into trouble. The only way they really get help is from the chase boat. If it weren’t for the chase boat being there these guys might not have made it. So sometimes our stories do kind of break the fourth wall in that regard.

Sometimes the production crew plays a role in the decisions the captains make. In this case, they were able to get them a part to help them. We play that chase boat out there as an omnipotent figure capturing stuff, but it’s a real boat and they’re facing the same dangers that everybody else is. They’re trucking through the storms and they’re taking the 40-foot waves and trying to capture great shots at the same time.

HULLFISH: Is there any rule about when you are playing lines on or off or is it more documentary style?

BUTLER: The rule is probably just to make sure that you’re capturing the intent of what the skippers are saying. And believe me, we would hear from them because we talk to them a lot and they come down to Burbank. You want to make sure you represent the intent of what they’re saying.

That said, our producers in the field are great about getting exposition two or three times a day. So, in the morning, they might get a little setup bite about what their goals are for the day; where they’re going to fish. We might have to repurpose that and use that later on in the day, so we will pull stuff from the same day that helps, usually for exposition purposes.

There are audio running 24-hours a day on all the different decks, so if we don’t have it on camera we might pull some audio that was recorded on a deck cam to help support just the basic information about what they’re trying to do and what they’re accomplishing.

MOORE: But there’s a lot to look at. You want to be on deck. You want to be in the boat-to-boat. You want to keep the captain alive, but also everybody else.

MIKAN: And sometimes we’re paring bites just for time compression. Like there’s a scene that plays out over 20-minutes and we only have a couple of minutes to show this, so we have to pull up time but we always want to see somebody say something when it’s important.

HULLFISH: Throughout some of the episodes there’s back story segments — kind of character intro pieces. How are you determining when those pieces fit into the overall structure of an episode?

BUTLER: The executive producers, the showrunners, they have constant conversations with the cast before the cameras even go up to Dutch Harbor. So they have a sense of what their goals are for the season and what their stakes are so that when Scott Campbell Junior — the captain who hasn’t been on the show for about five years — came back this year, we knew his situation.

He hadn’t been on the show for five years. He had to leave because of a debilitating back injury that was just a chronic condition. He had been talking to Arum and we knew that he was interested in coming back on the show and letting us follow him.

So you know, going into a season, what you hope or maybe you just have a hunch. You do basic reporting. Sometimes you cover something because you know this probably will turn into something. There’s a ton of setup scenes that we never use. They shoot a setup scene for everybody because you don’t know where that’s going to go — if that character will become important. So they’re really good about covering the bases and just casting a wide net with those setup scenes so that we know if that story becomes juicy and develops we have the ability to create a nice set up for them.

MOORE: That happens down to crewmen too. The executives say, “We’ll want to intro this guy in episode one because he’s going to cause a lot of flak in episode 3 through 5.”

So determining who’s going to be a main player and then making sure that those people have voices throughout the entire series.

HULLFISH: I kind of got that impression from the introduction that Russian crew guy that they needed to bring on.

MOORE: Vasili!

CAMP: Yeah! Vasili!

HULLFISH: Am I gonna have to tune into later episodes to see what happens with him.

CAMP: Oh yeah!

HULLFISH: There was also another crew guy that they convinced to come to Dutch Harbor to replace the other crew guy that got kicked off for being high. Did you shoot his trek to Dutch?

MIKAN: Oh yeah. That moment was totally authentic and no one knew it was going to happen. Bill showed up and these two guys didn’t come back to the boat because they were out partying all night. So he gets to the boat and he has to fire half of his deck crew immediately at the beginning of the season.

Once we did realize that that happened and that was in the material, then we want to establish him at the beginning. He was going out there with the veteran crew — fully stacked — the best possible way to go out there, so it was critical that we established how ready to go they were so that it turns into a big record-scratch moment when he gets to the boat and these two guys were out all night partying.

BUTLER: They cover everything. A lot of times those stories just don’t go anywhere. In that case, if you look in the footage, it’s all there. They’re probably meeting the other deckhand that we don’t focus on, but since that story didn’t go anywhere it just hit the cutting room floor.

That’s kind of the blessing and the curse of having 15000 hours is that there’s always some truth in there somewhere. You can find it. It’s documented — whether it’s on a deck cam that you have to chase down somewhere — or you have to scour the logs for.

As Joe said, sometimes you find an event later and you have to reverse-engineer it. Meaning you have to set it up and make sure the audience understands how we got to this point. And it’s all there. It’s just how much do you want to dig? How much do you want to chase it down — like an archaeologist? You’re just finding this one little thing that makes it all clear and come together.

MIKAN: And that’s why those shots were so dirty in that scene because the camera operators were just grabbing their cameras and running onto deck to get that story because nobody knew it was going to happen. And we love those dirty shots on this show where the camera is shaking and being picked up and following the action because it really adds to that sense of realism.

HULLFISH: This has really been informative. Is there anything else you guys want to talk about before we wrap this up?

MIKAN: I just want to say how grateful I am to be working with such a creative and talented team of editors. I think there’s ten of us on board this season. It takes every single one to get these things finished and I want to give a shout out to the editors that could be here with us for the interview — Greg Cornejo, Alexander Rubinow, Ian Olsen, Alberto Pérez, and Josh Stockero.

CAMP: And Ralph Melville.

MOORE: And Art O’Leary as well.

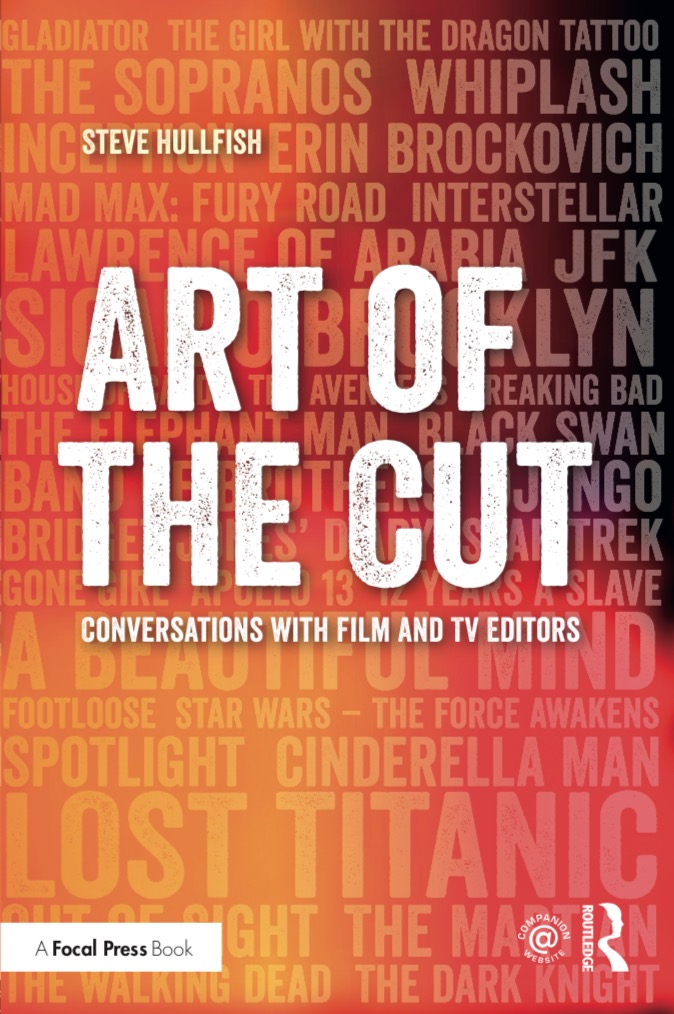

BUTLER: Steve, we really appreciate you having us. About three years ago, Joe gave me a gift of your book. So Joe’s been your biggest fan forever.

BULATAO: This is my gift from Joe! (holds up Art of the Cut book).

MIKAN: I’ve been known to give your book out as gifts to other editors, so this is a real treat.

MIKAN: I’ve been known to give your book out as gifts to other editors, so this is a real treat.

HULLFISH: Well thanks for thinking enough of the book that you want to give it as a gift. That makes me feel great. I really appreciate all your time. It was wonderful talking to you.

GROUP: Thank you so much.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed, and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema. AND, it is given out as gifts regularly by Joe Mikan… and Eddie Hamilton…

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now