As if 2020 hasn’t been disruptive enough, Apple capped off the year with the launch of Big Sur (macOS 11) and the release of its first Apple silicon-powered M1 Macs. It’s hard for an editor to keep up with these changes, let alone post facilities operating multiple workstations. Mac users have now reached that fork in the road. Do you update to Big Sur on your existing hardware? Should you buy an Intel Mac now when M1 Macs hold such promise? Or should you jump ship entirely and embrace Windows?

Operating systems

Mac users are quickly being pushed to Big Sur. Apple has dropped support for 32-bit apps and no longer includes 32-bit library components within the operating system. Big Sur is a melding of macOS and iOS, both in architecture and interface design. If you use applications purchased or installed through Apple’s Mac App Store, then you will likely have encountered a few recent updates, like GarageBand, that will only install if you are running Big Sur. Some, like the latest Final Cut Pro 10.5, won’t show up if you are running Mojave or older. For most, macOS Catalina (10.15) is the minimum compatible version. That also holds true for many third-party applications. If you want to continue to play in the Apple software ecosystem, then Catalina becomes a requirement. At some point in the future, the goalpost will shift completely to Big Sur.

It will take a while before many applications are truly compatible with Big Sur. This often puzzles users. They’ll ask, “Developers test advanced copies of the OS software, so why can’t they be ready on day one?” What most don’t realize is that Apple and/or Microsoft still make changes to the operating system between the final “gold master” release candidate and the official release version.

An OS update often changes certifications, permissions, and library paths. A hardware platform change alters the instruction set an application uses to tell the processing hardware how to handle that application’s task requests. Each presents a different set of challenges for every developer. Since every possible user configuration can’t be tested, things get missed, which is why you often see point releases with bug fixes following soon after the first release of an application, but more notably of operating systems. Seasoned users wait at least six months before diving into a major operating system change.

At the time of release, many mainstream NLEs and DAWs are not ready, but neither are most common plug-ins. A quick internet search will reveal countless manufacturer support warnings that their application, plug-in, or peripheral hardware does not support Big Sur and/or the new M1 Macs, yet. Lest you think this is just an Apple issue, let me remind you that Windows has likewise been on a steady path to move all of its users to Windows 10. That OS automatically pushes out frequently unwanted and unscheduled updates that on occasion have temporarily bricked or slowed computers.

Component deprecation

Deprecation became an issue for editors when Apple shifted to a total 64-bit OS and dropped all 32-bit QuickTime library components. This impacted media codecs, including Avid’s DNxHD. Like other developers, Avid had used OS library components within its application. When an OS developer (Apple) drops such support, the application developer (Avid) has to either develop their own internal replacement components or work with the OS developer to recreate new 64-bit versions. A codec developer wants their media to be playable with other software (Adobe, Blackmagic, Vegas, etc.). That’s exactly what we have seen. First, individual apps were updated to support DNx directly and now Apple has released a Pro Video Formats update that adds support for DNxHR within its own applications.

The hardware platform

If you purchase a new computer today, it will come pre-installed with the most current operating system. Windows users can often choose between home and professional versions of Windows 10, and in some rare cases opt for the older, unsupported Windows 7. A PC workstation buyer also has the option to install Linux as an alternative to Windows.

Apple users receive whatever is pre-installed without any choice. Often, when you are at the cusp of an OS change you might get the previous OS release, which at least gives you the option of updating, if desired. However, it’s a general truism that Mac computers cannot easily be retrofitted with an operating system that was older than the vintage of the machine. For example, I can’t but a new Mac Pro and install macOS High Sierra on it.

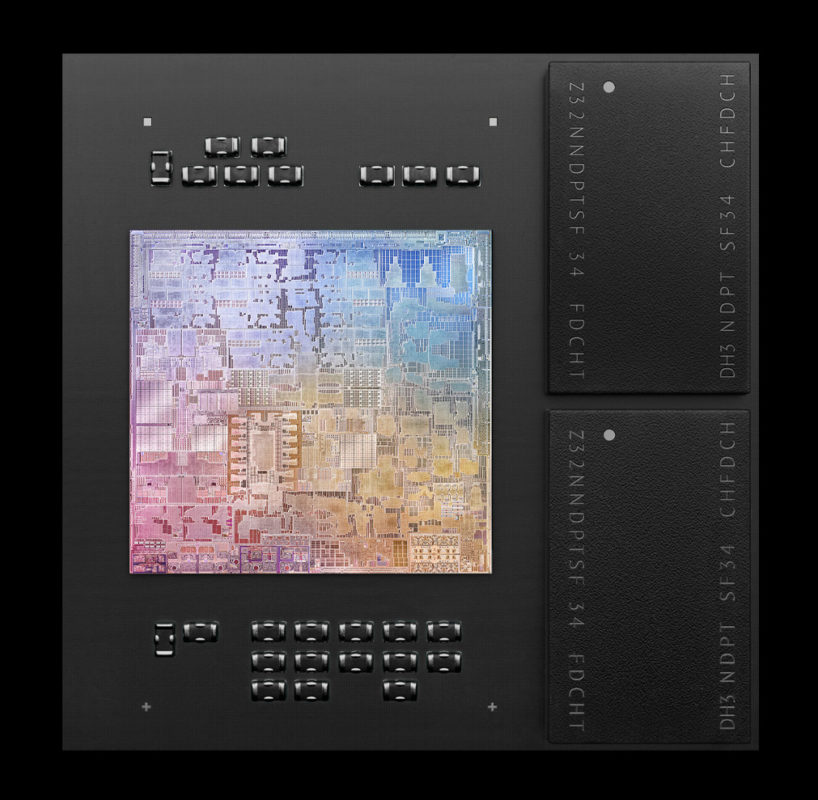

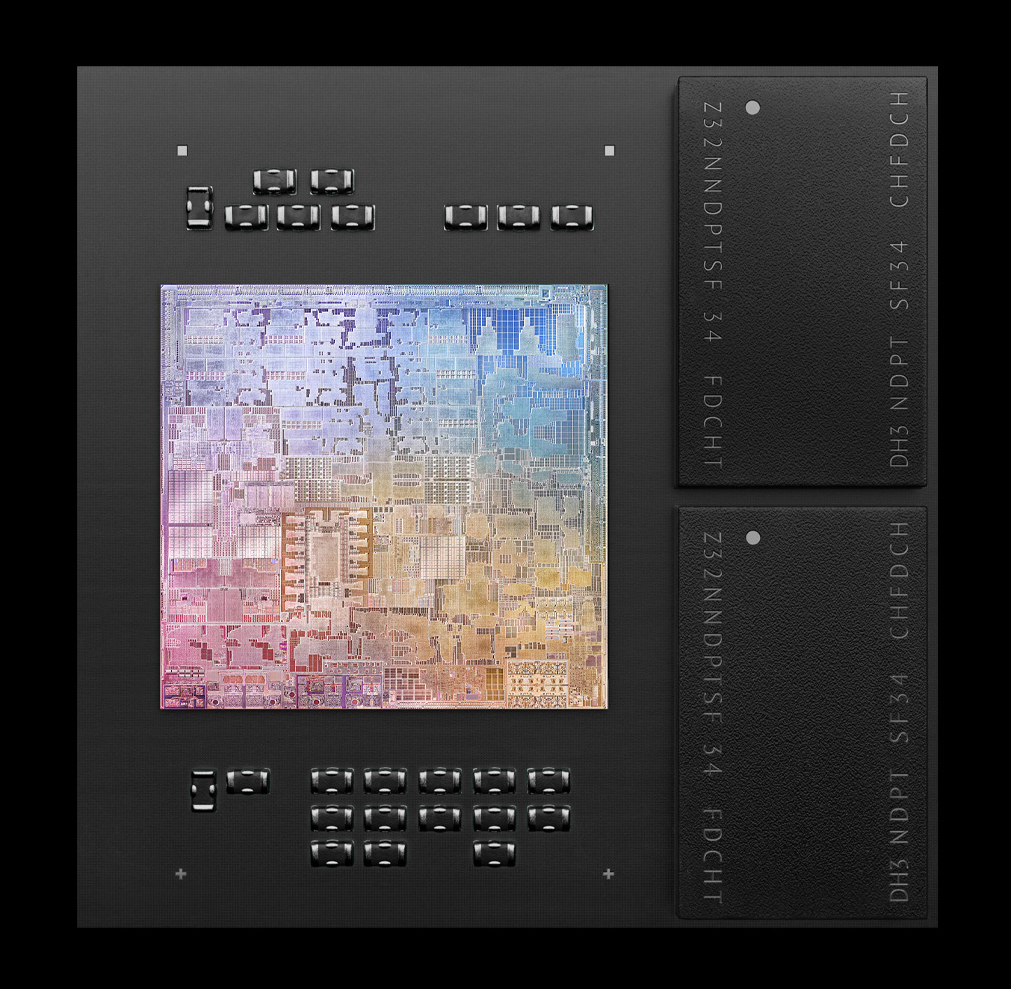

The launch of Apple silicon

The new M1 Macs present Apple users with a particular conundrum. While the new MacBook Air, 13″ MacBook Pro, and Mac mini are marketed as low-end products within the Mac lineup, their performance benchmarks have certainly redefined what “low-end” means. The M1 chips are Apple’s own Arm-based SoC chips (System-on-Chip). They integrate CPU, GPU, RAM, and a neural engine and are desktop versions of the chips powering iPhones and iPads. The M1 MacBook Pro and M1 Mac mini rack up benchmark scores and real-world testing results that rival the base 16″ MacBook Pro with an Intel chip and AMD GPU.

Only a handful of applications, like Final Cut Pro, are ready as native applications for these Macs. Few, if any, third-party applications and almost no plug-ins are ready. That’s likely to be the case for at least six months or more, especially among the more cautious developers, like Avid Technology (Media Composer, Pro Tools, Sibelius), Apogee (audio interfaces), and iZotope (audio plug-ins). Although the initial testing has been impressive, the reviewers and vloggers have been very selective by using a narrow field of applications. It can be argued that due to efficiency, the M1’s 16GB of unified RAM is comparable to 32GB in a conventional computer. Until we have further testing, it will be hard to know how RAM-hungry, non-native applications truly perform on M1 hardware.

To upgrade or not?

I decided to upgrade my own home editing system just a week ago (at the time of writing this). You might call me an idiot, but I opted for a reasonably-powered 2020 27″ Intel iMac. I need a computer that can deal with whatever work I throw at it, including Adobe apps, Final Cut Pro, Logic, Resolve, and Media Composer – plus a range of audio and video plug-ins. I edit at a facility on a daily basis with iMacs and iMac Pros, so I have a good understanding of what they can do. The M1 mini would certainly have been cheaper. If I factored in the cost of a 5K LG display and all the peripherals needed to compare Apples to Apples, then the two packages would really be very close in total price. Along with the Mac Pro and Intel mini models, the iMacs are the only current Apple computers that allow end-user RAM upgrades. Upgrades are not an option with these first M1 Macs.

I get it that Apple’s future development will be with these Apple silicon Arm chips. However, I’m also betting that there will be at least five years of support for Apple’s last run of Intel Macs. As an aside, if you need a Mac that can also run Windows under Boot Camp, then the M1 Macs are also not for you – at least not in this current iteration.

Naturally, if you a responsible for a fleet of machines, then upgrade choices become harder. Make the wrong move en masse and you’ve negatively impacted the entire operation of a post facility. This is one reason that TV series and feature film post-production often runs on older hardware, operating systems, and application versions. The systems are tried, true, and bulletproof. They are often supplied by a post vendor to the production company and that vendor may be responsible for hundreds of systems in their inventory. This is a key market for Avid Technology and one reason that the company has historically been cautious in their development path.

It’s a choice

All of this presents the individual user with a dilemma. The Avid or Adobe editor that needs to buy a new Mac today has a choice – a recent Intel (hopefully still with Catalina installed) or a new M1 Mac. The M1 will come with Big Sur and is not yet officially supported by any Media Composer or Premiere Pro version. If an Avid editor opts for the Catalina Intel Mac, this also means moving to the latest Media Composer version 2020, taking them out of the comfort zone of a more familiar (to many) Media Composer 2018 or prior. Change is tough!

For many, this makes the Windows ecosystem the more reliable bet. The good news is that most of the key applications (except Apple’s Pro Apps) are cross-platform. Adobe, Avid, and Resolve editors and colorists can readily shift over. Others may opt for older, refurbished Apple hardware, just to be able to stay on older, reliable application versions. 2010-2012 Mac Pro towers still abound and you can readily find new, old stock and refurbished “trash can” 2013 Mac Pros. The latter are good up to at least Catalina.

There are no right or wrong answers. Do what makes sense for your own needs and working situation. Avoid the lure of the shiny and new. There is no reward for living on the bleeding edge when you need to turn in good work on time and within budget. The good and bad news is that your choices are greater than ever.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now