Today, I’m speaking with Emmy and Eddie nominated documentary editor, Inbal B. Lessner, ACE.

Her work includes the feature documentaries Brave Miss World and I Have Never Forgotten You, CNN’s series of “decade” defining documentaries on the 70s, 80s, 90s, and aughts, The Two Killings of Sam Cooke, and Can We All Get Along, for which she was nominated for an ACE Eddie.

In addition to her documentary work, she was an additional editor on Natalie Portman’s directorial debut, A Tale of Love and Darkness.

Today we’re discussing her work on the Starz network’s documentary series, Seduced: Inside the NXIVM Cult, for which she worked as Executive Producer, Editor, and Writer.

Inbal Lessner, ACE editor, executive producer, and writer on Seduced: Inside the NXIVM Cult

Inbal Lessner, ACE editor, executive producer, and writer on Seduced: Inside the NXIVM Cult

This interview is available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about the project and your involvement, because you have a lot of other titles on this production, including executive producer and writer.

I’ve talked to a lot of documentary people that say documentary editors should ALWAYS get a writing credit.

LESSNER: I think they should.

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about how you came to be so intimately involved in this project on so many levels.

LESSNER: I work first and foremost as an editor. That’s how I made my career and made a living ever since I was in high school really. For most projects, I start as an editor and then receive other credits according to what other responsibilities I take on.

With Cecilia Peck, my producing partner on this, we had done a feature documentary called Brave Miss World that I think is still on Netflix for a few more days — it. That’s a project I also started with the idea that I’d be an editor but then ended up being a producer.

So Cecilia and I have been looking for another project to do together. She came up to me with the idea for a project about NXIVM (pronounced “Nexium”) because she had met these women who recently came out of being in this cult and she asked me to edit together a sizzle reel.

She had produced an initial interview with some of these women. I didn’t really know anything about it. I looked online and found some news reports and some pieces that were out at the time that we were able to download and integrate together with this preliminary interview and cut something together to present to Starz.

That really was our first meeting and she asked me to join her in the meeting and help her pitch it. We had the history of working together and I was at that capacity before. So that’s how I joined her as a producing partner.

It was clear that I would not be able to cut it all myself — especially in the timeline that this production demanded, and so I was the lead editor, and towards the very end, we convinced Starz to also give us writing credit.

As you said, I feel it’s always warranted for documentary editors to receive that credit. I was grateful I was able to get that credit and I share that with Cecilia as well.

HULLFISH: Is it more difficult with structure when you have multiple episodes or your story’s told over such a long period of time? Instead of — for example — one feature-length documentary.

LESSNER: We treated Seduced as one film — as a continuous four-hour feature. For TV we had to build “Previously ons” and teasers, cliffhangers for the end of the episodes. Also, each episode has an organizing principle — a different main theme that runs through it. But I think it really is a four-hour journey, so we didn’t treat it that much differently than we would a one-off continuous feature piece.

It becomes complicated when you have a large team to manage and everybody’s in charge of a piece of that puzzle.

We did have to make sure everybody was a real team player — that they would be flexible enough to give away a scene to another episode if that was the best place for it.

Not to say it was easy to find a structure, but once we did and everything fell into place it really felt like one long piece that was just broken up into four parts.

It was actually our intention to do five parts. We felt the story lent itself to that and — for Cecilia and me — the piece about healing and recovery was particularly critical and important to tell, so we didn’t want to do away with it and just end with the conviction of Keith Raniere at the trial.

We really wanted to follow these women and see how they put their lives back together — India Oxenberg and the other former members — how they were able to recover and find their voice again and speak out and perhaps affect change moving forward. That piece of healing and recovery was the idea for the fifth episode and we had to fight the network a little bit for that.

The compromise was to make a supersized fourth episode. So the fourth episode runs 80 minutes long and it does have all of the pieces we were hoping to get into it.

HULLFISH: When you were doing that writing and that structuring, is that something that you found that you needed to do on a wall or in writing, or was it something that you discovered actually in a timeline of an editing system?

LESSNER: It’s probably a combination. When you work with multiple editors and a story team — there was a story room — you have to adjust to what everybody’s comfortable with and their own process of getting to where they need to get, creatively.

There were a lot of cards on walls — multiple walls, multiple cards — there was a huge wall in the story room that was evolving with cards in different colors.

I really have developed an aversion to paper, so my thing is digital storyboards and so I have a template on Google I like to work with and we also tried Miro for the first time for storyboarding.

I just like the idea — especially after COVID hit — but even when we were still all together in the office in 2019 and the beginning of 2020, the ability to take my board with me home or share it with people who are not in the office or in another room and just move those digital cards around and add detail to them and erase it without dealing with too much paper.

So there was a lot of storyboarding going on. There were a lot of outlines and extra documents. The way we worked with the network — every time we came with an idea for a scene or a shoot, we had to formally request that shoot approved by the network, and so it kind of forced us to really dig into — with every single scene — what we were looking to get from it.

This is unscripted, but in an ideal case scenario what that scene would tell? What would be the beginning, middle, and end of it? We planned carefully and then we still let it surprise us when something else happened in the field. But we had to produce a mountain of documents for everything we wanted to shoot and then report afterward what actually was shot and then start putting outlines on paper.

So we had multiple versions and formats of this evolving script and structure.

HULLFISH: You used some very artistic animations. This is a sensitive topic and I’m sure you could have sensationalized it and done full-on recreations shot on film.

Talk to me about the use of those animations. When did you get them or when did you know that you were going to use animation?

LESSNER: When we were first conceiving the series and developing it in early 2019, we were waiting for this trial of Keith Raniere to start and we knew there were no cameras or recording devices of any kind allowed in the courtroom.

Initially, we thought structurally that the trial would run across the entire series. It would be the way by which you learn about what was happening in this group.

Initially, we thought structurally that the trial would run across the entire series. It would be the way by which you learn about what was happening in this group.

Eventually, after India Oxenberg joined the project, we found a more linear structure to it and the trial took a backseat, and we only show it when we get to it chronologically in the story.

So when the trial was going to be a bigger non-linear component through the story, we were looking for ways to visualize it and figure out how to tell those stories that were in the courtroom and would only be available through our subjects sitting there and talking about it afterward, or through the courtroom transcripts.

So we started looking into different types of visualizations and animation ideas. It was later on after India actually had joined a project in the fall — she started binging on documentaries on the weekend and we all would try to binge together on the same films and she watched Miss Americana — the Taylor Swift documentary — and there was this tiny little segment there about a court case that Taylor Swift had against somebody who assaulted her sexually.

And it was really a short scene, just a few illustrations, but they were done so beautifully and managed to evoke so much emotion by not being too literal. They were more suggestive. I was just really liking the feel of it, and I contacted the producer of Miss Americana — who I’ve worked for before — and she connected me with Elyse Kelly, this amazing artist based in Washington D.C.

Elyse brought on her team, and luckily Starz — out of the few artists we pitched — was really into her artistry and voice and liked her early samples.

As we started working with Elyse we wanted so much animation. We realized this could really help bring to life, not just the scenes that we didn’t have visuals for — because cameras were not rolling or we didn’t have enough access to photos — but because it was an emotional milestone that needed to be told in the most evocative way possible. But animation is expensive and it takes a long time to produce and we definitely were not budgeted to spend that much money.

Luckily, Starz saw the vision — understood our need — and they were supportive enough that we were able to get some illustrations. Elyse found a way to make them moving — we called it “boiling texture.” So there are some scenes that are 2D paintings that are not moving, not animated, but they have this boiling texture that makes them feel like they’re moving, and in the Avid we added very slight movements in and out or across to make it feel more alive.

And then some other sequences are fully animated and those are really special, and we knew there were some core moments that definitely warranted that treatment. The branding scene was certainly the first one where we knew this had to be done. And this was one of the first tests that Elyse did with us.

It was a real collaborative process to find the right tone, the right colors, the right imagery so it doesn’t feel exploitative even when they’re all naked. It couldn’t feel pornographic. It had to feel like the emotion of being in that very traumatic situation. So it had to feel like shreds of memory, kind of infused with all the trauma, and give you a kind of a sneak peek into those memories.

If you follow just the animated portions from episode 1 through Episode 4 you’ll see that the color palette, the clarity — it gets darker, it gets less cohesive. The tone shifts gradually towards the kind of most abusive, horrific scenes in Episode 3 and then comes again into clarity as India walks out of the courtroom in the final animated scene of episode 4.

There was a lot of thought put into it and sometimes Cecilia and I would lie on the floor and contort ourselves and try to take photos of ourselves just to simulate what body position should be illustrated in the animation so that we can convey to Elyse how we saw those things. It was really a fun part of the process and I wish we could have more of it, but I think we ended up with just enough.

HULLFISH: Did you edit together the photographs of yourself into something like a story reel for the illustrator?

LESSNER: I think we did it once. With Elyse, we didn’t have to over-explain just because she’s so intuitive, and some of the ideas she came up with…

There is a scene towards the end of episode 2 where Allison Mack pitches this idea of the secret sorority to India Oxenberg and they’re crouching behind a table during a NXIVM event. Elyse came up with this idea of how to illustrate Allison showing India what this secret sorority is about, and how you could push against your fears to really reach your full potential.

She made this tiny version of India running back and forth between their hands into this idealistic state. I can hardly explain it in words but what she did visually was really the essence of what that pitch felt like, and it helps understand how anybody could even say yes to this crazy master-slave group.

Editorially, it was really the biggest challenge to help you understand this very strange world which took me personally months to really grasp and get a clear picture of all these different classes and courses and the web of programs and companies and sub-companies.

How do you then boil India’s first five years in the group down to 90 minutes — showing the gradual indoctrination that made her get to the point where she would say yes to being in a master-slave program?

HULLFISH: I was really touched by India’s mom talking about the guilt that she felt for her role in accidentally getting her into the group. That was some really powerful stuff.

LESSNER: Yes. I think the mother-daughter story for us is — if not the A story, definitely a strong B story — and the kind of story both Cecilia and I are very interested in. I come from a family of three daughters, three girls. I have my own two daughters. The dynamic between mothers and daughters is something that I find fascinating.

When we met India over a year ago — when we started filming with her — she was in a very different place. She didn’t really understand all the dynamics. Didn’t really understand the difference between what they made her think was happening versus what was really happening. And the relationship with her mom was one of these things that was still collateral damage — a casualty of the years in the cult.

They weren’t able to communicate clearly. There was a lot of resentment and anger there. Some very complex stuff. So to tell that story and then have them at the end come to some resolution and understanding was a very powerful narrative to follow.

HULLFISH: Did you feel that it was important to have a female team around you for this type of material?

LESSNER: Very much so. Even though we filmed some interviews initially with male former members, we had a very clear point of view that this story had to be told from the perspective of female former members. A lot of the teachings were thinly veiled misogyny and the women suffered incredible abuse, sexual abuse.

There was a woman we interviewed who had a mental breakdown — she suffered a psychosis as a result of these workshops — so we felt that in order to give them a safe place to tell these stories in a way that felt honest, supportive, and respectful of their trauma, we needed to have women in all key positions in the production. So from the two network executives through the showrunners, Cecilia — the director — our main cinematographer, camera operators, sound recordists, all the way to PAs and assistant editors -. Not to say we didn’t bring on very sensitive male allies along the way, but it was a female dominant production and we feel like it had to be that. We established protocols for how to handle and communicate with these women on the set as well as before and after, and we invited them to the editing room several times so that they felt part of the process and they didn’t feel like, “OK. We got your story on tape and now we get to exploit it however we want.”

We didn’t always tell the network that we were doing it, but we allowed them to come and fill in the blanks — help our editors understand some of the things that were difficult to understand.

They would visit and they saw some clips along the way and when India joined she became involved and she watched some things. She didn’t have final cut, but she did have to be involved enough in the building of the story to understand what we needed to tell it properly.

HULLFISH: You must have done multiple interviews over the course of several months, especially with India.

LESSNER: We hide it, right? Because we make it all the same setup, but yes, there were multiple days of interviews. There were some incredible, beautiful, heart-wrenching stories that she told the first day. But there was also a lot more clarity that we gained from living with this and cutting this and developing the story in the edit room and things she realized — she remembered later — things that she didn’t quite understand or process or remember the first day.

So some of these things come out in verite scenes, in her meetings with experts, in just talking on her own when she goes back and confronts the places where all these traumatic things happen and some of it comes out in sit-down interviews.

HULLFISH: I’ve worked on some documentaries where everything was shot before I started editing. I’ve also worked on documentaries where I was able to get more material during the edit.

Speak to the value of being able to get more material as you are editing and seeing, “I need this connective tissue. I need this explained.”

LESSNER: Yeah. It was critical for this story because there was so much to unpack and so many directions and threads we could have taken — and DID take — and had to then give up and abandon or really distill in order to stay on this main track.

We didn’t have eight or 10 or 20 hours. We really had to be disciplined on how concisely we had to tell this very complicated story. And the ability to see what works, what doesn’t, cut something together and brainstorm together with your story team.

We could say, “It would be great to shoot this person now moving out or this person now having a confrontation or discussion about this aspect that we haven’t fully developed.”

Yes. It was incredible to be able to keep filming and I think Starz initially thought we could have the whole thing done within six months — that was the idea — from beginning to end with about 12 to 14 weeks editorial per episode.

But it just needed more time to cook —for us to make sense of the archival — this inside footage and how that connected to India’s experience. How some of the stories intersected and overlapped — where were those significant overlaps?

When was the moment where, for example, Kelly — who was a coach in the program towards the later years of the story — ends up going to teach a class in Albany and sees India Oxenberg and asks her how she’s doing. Because as a mother Kelly has a sense that something’s not right with India. And so they wanted to have a conversation about this and we shot it later in the process and that was a very special moment.

One of the final scenes where all these women team up and go to speak to law students in Episode 4 — to talk about the need for coercive-control legislation and how they find their own voice and speak together, and how impactful that can be for future lawmakers and for our understanding of the need for such legislation.

So, yes some of these later scenes that we were able to capture are really extraordinary and they feel earned because you have the benefit of the many months of shooting. There was a real process of learning that India went through, and the other women also came to understand things about their experience because they sat in that courtroom and because they had time to speak to therapists.

Our relationships with them developed. They were able to see things in the editing room and then reflect on them. So all these felt like a maturity that had to be earned.

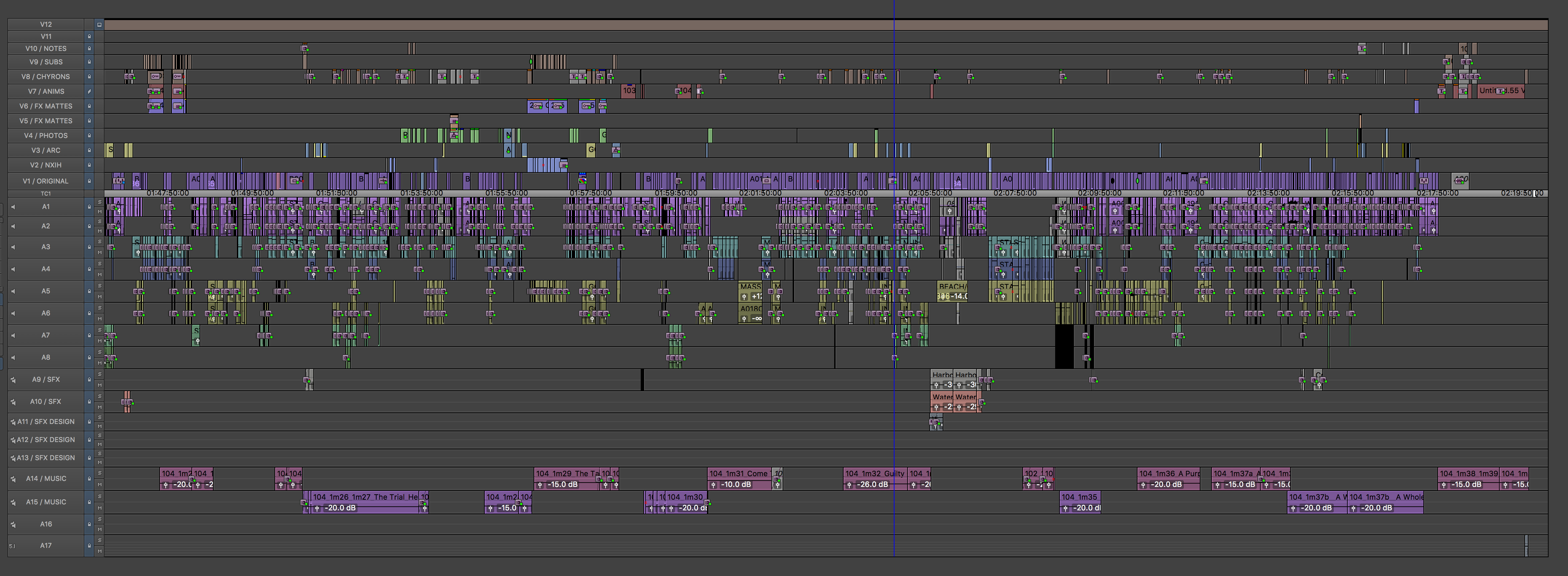

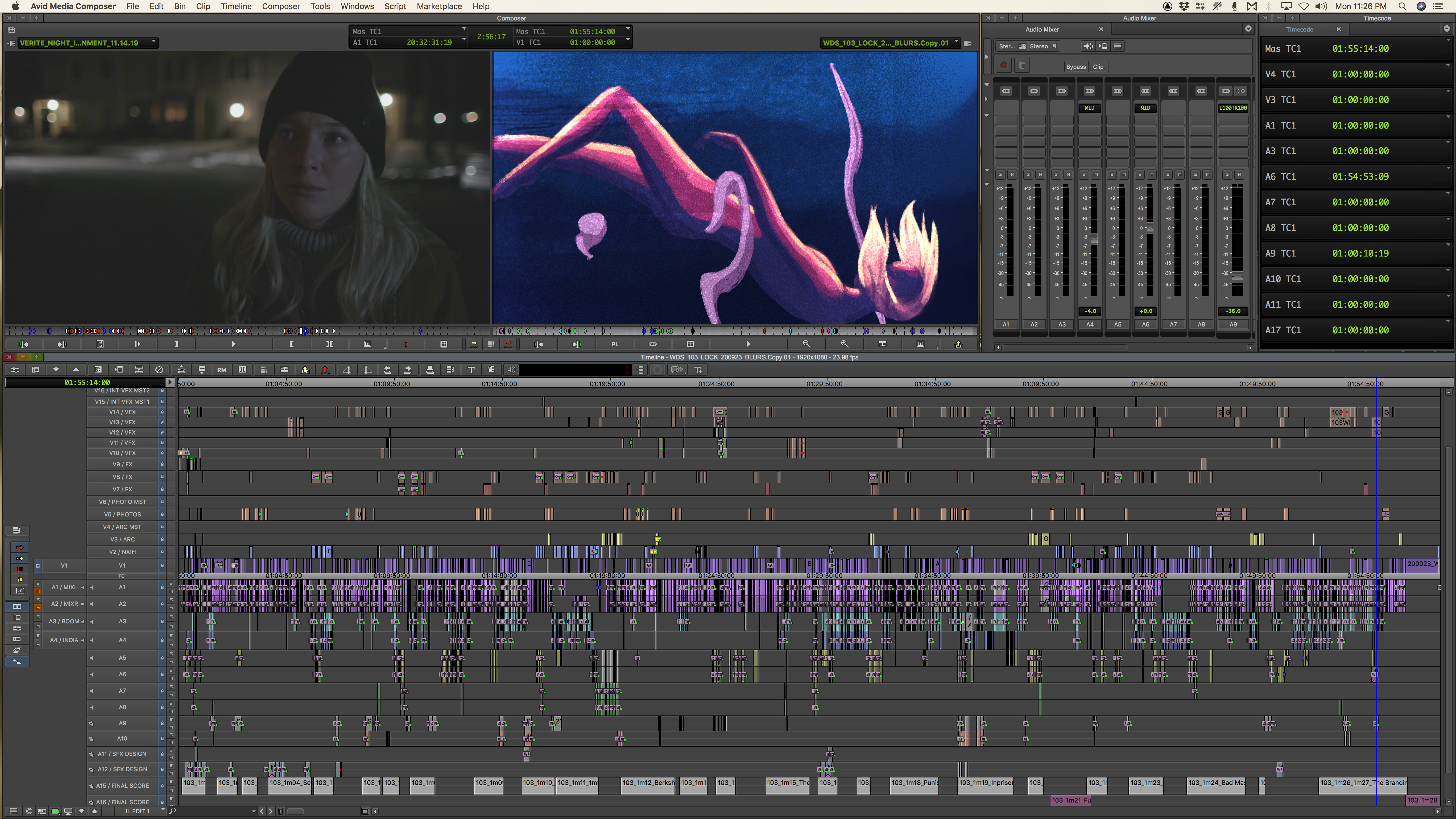

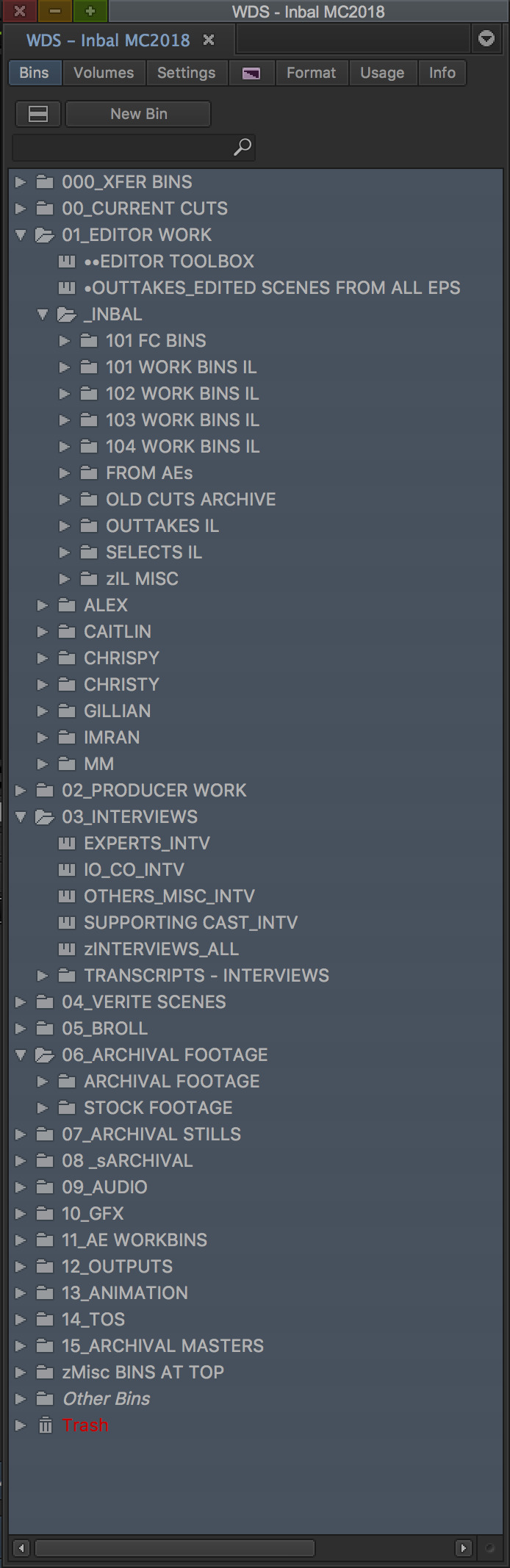

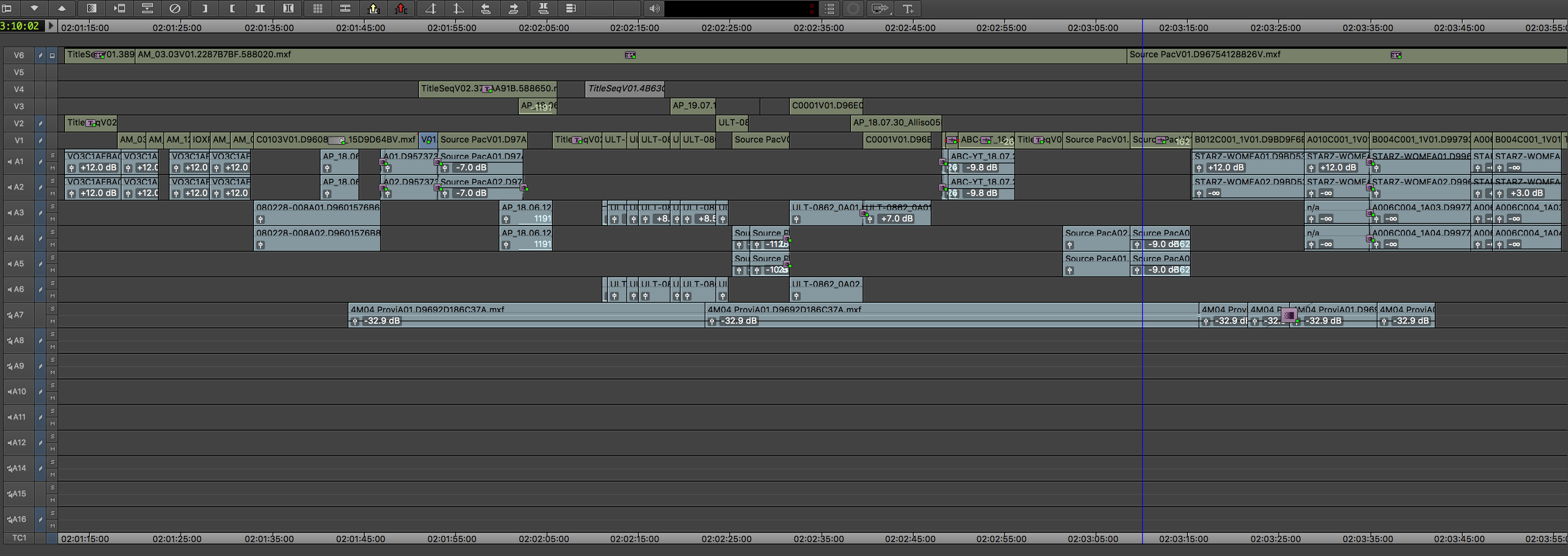

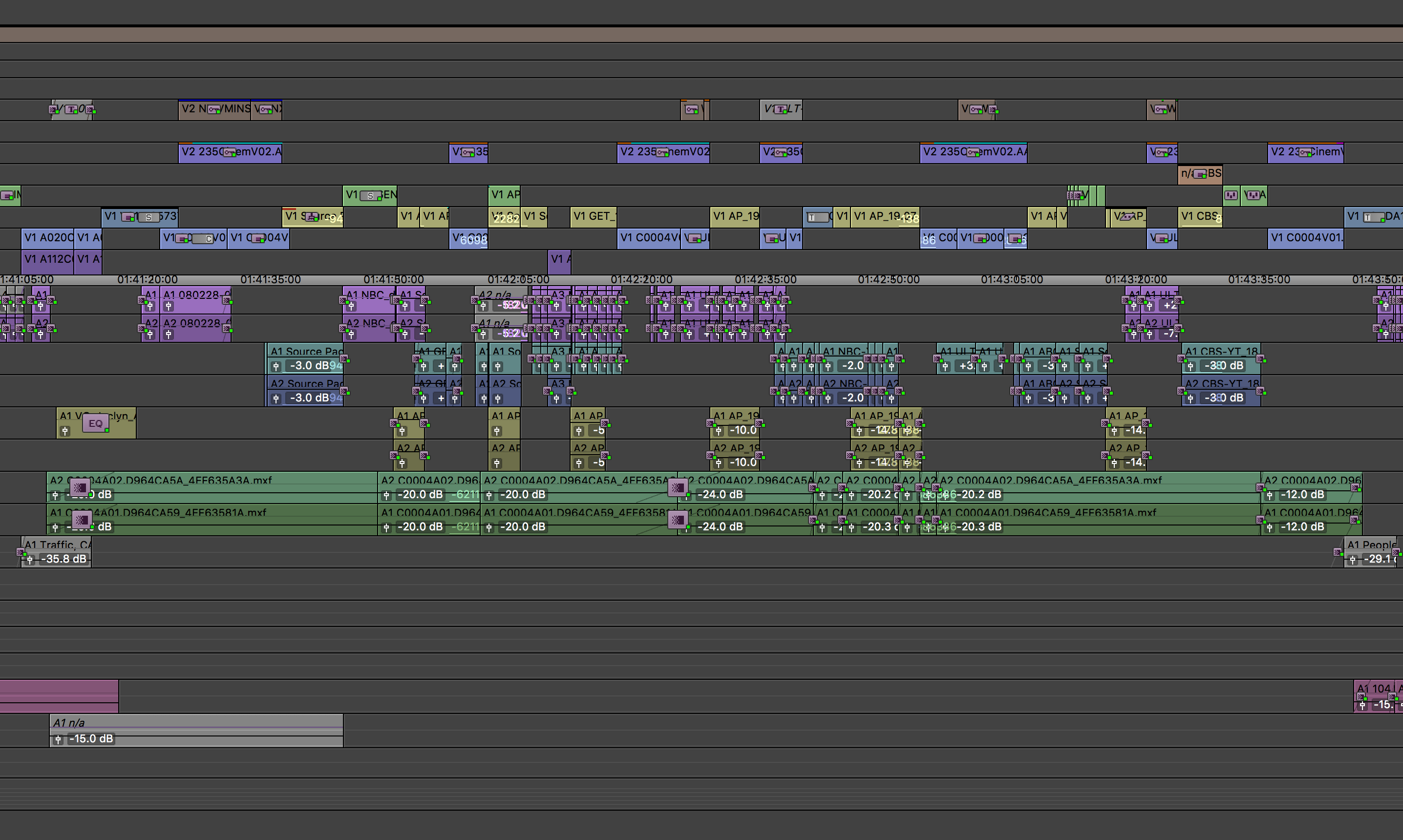

HULLFISH: Talk to me about organizational principles. You said you edited in Avid, I believe?

LESSNER: Yes.

HULLFISH: There’s just a ton of material. You’ve got all of this archival material that came from the cult itself that you guys found. There are all the interviews you did. There’s verite stuff. There’s animation.

LESSNER: There are government documents, recordings.

HULLFISH: What was the organizational principle? How did you find stuff when you had a story to tell?

LESSNER: I think the core tool that we use is ScriptSync. I really can’t fathom doing a documentary project without ScriptSync.

HULLFISH: I’m finishing a documentary project right now that I would still be working on the rough cut if it weren’t for PhraseFind and ScriptSync.

LESSNER: I use it all the time. Every minute really to search for words and ideas and phrases and review.

Yes. It cuts down the time but it also really helps you put that story together. So all our interviews were transcribed and “Script sunk.” Some of the verite scenes that were dialog dense were also transcribed.

In terms of organizing, I like to have the material available intuitively and that means a certain clip can live in more than one place — in fact in multiple places.

So while we have the footage organized by day — like regular dailies — we also have a lot of organization by theme. So we’d have a theme of sexual assault or a theme of the gender-related programs and teachings. We had it organized by characters, so anything related to Clare Bronfman — the heiress that bankrolled this organization — anything that had to do with her; news reports about her, would be kept in the same bin.

We had extraordinary assistant editors who kept all of that organized and we couldn’t really do anything without them.

And the search tools that Avid has improved — probably with the pressure from Premiere — are becoming better and better. You can search bins and inside bins and I have my own color coding with markers — formerly known as locators.

We have color coding and certain keywords that everybody follows. So I know as the showrunner-lead-editor, I just don’t have enough hours in the day or in my lifetime to watch every minute of material, and so, in terms of organization, on all my documentary projects I empower my assistant editors and loggers — I really tell them, and I mean it, that they’re the most important people on the entire team because they get their eyes on every minute of material that I can’t always get to.

And so I encourage them to yell at me through these markers. If something is funny I tell them to put a smiley face and sometimes I will just look for a smiley face because I remember there was something funny in the scene and I just want to get to it quickly.

So we log every piece of footage very meticulously and with the same system — with the same keywords and color-coding so that we all speak the same language and when I search for some word, I can find what I’m looking for.

And then, of course, I have bins and bins of little outtakes and sub-clips and my own selects. So I do interview select and I do verite selects and I do archival selects and that’s my own little bank. So if I walk into an edit room to work with one of my team members and they work on an idea and I remember in my head, “Oh! I have this clip!” then usually, I can find it pretty easily.

HULLFISH: You don’t use PhraseFind at all?

LESSNER: One of my editors that I worked with had PhraseFind at home and he said it helped him find some new things and he was kind of having fun with it. I haven’t had too much success or experience really working with it. So, no. Not yet.

HULLFISH: You sent me a couple of clips to look at from the movie. One of them was that very difficult scene of the branding of the women and animation is used in there as is music. Could you talk to me a little bit about the use of music and either what you temped with or how far into the post-production process did you know who your composer was?

LESSNER: So in full disclosure, the composer of the series is my husband, Daniel Lessner. He’s an extremely talented musician and concert pianist. He has scored several of my films before. It was far from being a done deal when we started, but I used his library as a resource for my cuts even when there’s no chance he would be hired.

It’s just my go-to resource for temp music because he has such a varied, extensive library in a lot of different styles. So I just brought it all into the office and I told the editors, Just play around with whatever you want. We didn’t necessarily have a very clear style and we just tried different things.

Cecilia — the director — had an idea in her head of this being digital score. It wouldn’t involve any kind of real-life instruments. It should all be synthesized. She heard some things I think in the theater that inspired her to explore this kind of digital soundscape and had very strong ideas about that, as she does about music always.

I knew Daniel could deliver that type of music and he had a lot of experience doing that, and so I explored some other musical ideas that he was just roughing out on a piano in our house. And I said, Well this is starting to sound like brain-scrambling to me. When you do these kinds of messy scales which is kind of Philip Glass but not really — and it has another layer of dissonance and is syncopated.

I have a background in music, as many editors do, so I had ideas of what the structure of the music should be and that it should reflect the character’s state of mind. How do you use the music to explain somebody is being brainwashed and made to go to very dark places and make decisions they wouldn’t otherwise make, and so can the music really help us tell that story?

So we tried different temp, but once Cecilia had time to articulate her ideas about the digital score, Daniel did some tests with what that might sound like and took some of the themes and pieces I liked and gave them digital treatment and so it evolved that way, and then, around our second rough cut, is when he was officially hired and started producing original music for the episodes.

At that point I was so over my head with picture-lock that I had to — in the interest of finishing the series and in the interest of domestic peace — I had to step away and just let Cecilia and Daniel go at it. I have to say it was magic because I kind of let them do it and very rarely interjected.

For the most part, they just did it on their own and I just got to drop it as I was picture-locking and just let the magic play out and I was pretty shocked because we had a very opinionated network executive and they had zero notes on the music. They just really loved it.

HULLFISH: I loved the music as well. It’s just fantastic for the theme and the tone of it.

LESSNER: Thank you. It has a lot of soul and you wouldn’t expect that from an all-digital score. Luckily that was the decision before quarantine because we wouldn’t be able to produce anything else really, so the choice of an all-digital score worked in our favor in terms of just finishing it on time.

I love how it develops. There are repeating themes. There is the brainwashing theme and there are different storylines that get different musical themes and at the end, it all builds back to that one sort of overture that you hear in the final end credits.

HULLFISH: One of the uses of music is NOT score. I wanted to talk to you about a section that you called the Moonlight Arrests and you use a piece of Keith Raniere playing piano. You don’t know that it’s not score. You hear this piano come up underneath and then you realize somebody is actually playing the piano. Talk to me about that.

LESSNER: It’s a lot of people’s favorite scene in the whole series. I think it’s brilliant, and I can take very little credit for it. It’s really a special product of amazing teamwork. Our senior story producer — Tara Anaïse — had this idea of intercutting these arrests with these women making statements, professing their devotion and love for Keith Raniere.

Those are all statements you’ve heard earlier in the series — in Episode 1 mostly — and we come back to those same clips, but replay them in this new context and the juxtaposition is really cool.

So we had an editor putting it together very roughly when that episode was still two and a half hours long. It was just a beast of a lot of content and narrative and information that we had to get through.

At some point, our editor Gillian McCarthy, who’s really brilliant, inherited that section and she found this piece of Keith Raniere playing Moonlight Sonata on a piano. And Keith was touted not only as the smartest man in the world and a scientist and a genius but also as a concert pianist. And it’s kind of funny how little piano you have to know to impress the hell out of people.

It is one of the pieces that you can play fairly well after a year or so of learning piano. It’s not the hardest piece but somehow it impresses people. So he sits down in one of their retreat spaces — a chapel — with a piano. Gillian really wanted to use the piano playing. We looked at it together and I told her definitely in the arrest montage. So I left the editing room and I come back at the end of the day or the next day and she put this together and it was just brilliant.

It feels like the Godfather montage of everybody being arrested as they’re falling on their sword for him and he’s playing this piece. As you say, it starts as score but then you realize it’s really him playing and at the end, he flubs the end of it. He can’t even finish it properly and he says, “Oh well!” It’s like he just ruined the lives of all these people. They’re all going to be in prison for a long time. It’s as if he’s telling you “I’m a psychopath and I don’t really give an F about it.”

It’s a really interesting marriage of ideas that resulted in a fantastic scene.

HULLFISH: It’s so interesting that you would say, “Put it with the arrests.” It’s not “arrest” music. But, as you pointed out, it’s brilliantly edited in that here are all these people — as you said — falling on their swords. The editor obviously back-timed it. It wasn’t just luck that it ended up with him messing up the notes on the piano and then saying, “Oh well! Too bad!” And that is the punctuation at the perfect moment of all these women as their lives are being ruined. Stunning!

LESSNER: The first time she put it together it was maybe almost twice as long. And we had to shrink it. I think that final distillation of it really made it pop.

HULLFISH: There’s another really interesting juxtaposition that I love that you kind of hinted at which is in the scene that you called the India tapes which was really the trial itself and India kind of getting over Keith. Saying, “Hey I saw him in the trial and he seemed small.” Then it cuts to a neuromuscular trauma specialist and is it intercut with the trial?

LESSNER: It comes sort of in the middle of the trial before the conclusion of it.

India — who’s been on the witness list — so she’s basically on standby to take the stand and testify against Keith Raniere. She has to deal with that tension, anticipation, anxiety, and nightmares as she’s hearing about the trial unfolding. She just knows that she’s on stand by.

Cecilia’s true gift of empathy and connection with her subject is what allows her to capture such an incredible scene. It’s just in a tiny little room. This neuromuscular trauma specialist — who does this bodywork in a tiny room in New York City. And India — who’s had a difficult time responding to talk therapy because of the experience in NXIVM, she wanted to share with us that she’s used non-typical and non-traditional forms of therapy.

She says herself, she was very privileged to have access to a lot of different forms of therapy and healing as she’s trying to get out of this and heal from this terrible, terrible experience.

She allowed us to go to the specialist that she was seeing in New York City and she pushes on certain pressure points, and at some point, she pushes on that side of India’s hip where she had that brand — where she has this very physical trauma on her skin.

It was just a tiny moment in this one-hour session, but India really breaks down. And I remember Cecilia called me because I was not on that shoot. I was on many of them, but on that one, I was back in L.A. cutting.

She called me after this happened and she said, “We have to use this. This was an amazing moment. I don’t even know if it was captured properly on camera. We were there for an hour but there was this one moment towards the end, please find it and see what we can do with it.”

So we had this scene that we tried to use in different places of India having a real moment of very visceral confrontation with her trauma. We were approaching picture-lock and there was really still no place for it. And I was editing in the shower as I usually do.

HULLFISH: Not literally, hopefully.

LESSNER: No! in my head!

HULLFISH: I do the same thing. Totally understand.

LESSNER: Yeah, right? I tell producers, You should let me go sleep because I edit in my sleep and edit in the shower. I process those dreams in my morning shower and that’s when I know what I need to cut that day.

HULLFISH: 100 percent.

LESSNER: And so, as soon as I got out of the shower, probably was still in my towel, I texted Cecilia, “I think I got the idea.” We’d been trying to construct this moment for India to reckon with her guilt — which was a very significant part of her process.

We’d had scenes that we’d had to cut where India actually talks to people she tried to recruit and ask for their forgiveness. We didn’t have access to women who she recruited into DOS (the deeper master/slave sub-group of NXIVM.)

There were a lot of pieces of audio — both in interviews and in therapy and in different places — where she talks about this immense guilt of looking at herself and confronting the things she did and thinking she was a monster. And how was she capable of doing some of the things they made her do? And can she live with herself?

And I realized that that was a perfect marriage of that visual of India getting the bodywork and having this cry over her own trauma and her culpability in the organization. She was just told that she’s no longer needed to testify, and she’s trying to figure out why this happened, how she let it happen, and can she still be useful in some way?

She really thought testifying was gonna be the thing that would help her find resolution and closure and move forward and then she doesn’t get it. The scene really kind of helps bring home the pain, the confusion, the unresolved feelings and then later she figures out what to do with that.

Initially, we had the therapist explain how she releases the trauma that’s trapped in the fascia, the tissue that surrounds the bones, but ultimately we didn’t need her to say anything so we cut that dialog out and we just let the images and India’s thoughts carry that scene. That was just beautiful and wonderful.

HULLFISH: Inbal, thank you so much for letting us in on your process. It’s really a fascinating documentary. Very hard for me and probably for you, I would think, to watch. When you were working on something like this for so long how do you deal with the darkness of it or the difficulty of watching some of this content?

LESSNER: Thank you for this question. I think that doesn’t get asked often enough.

I’m actually a member in an organization called ADE, Alliance of Documentary Editors, and we had just started a mental health committee that attempts to address issues of mental health for editors dealing with second-hand trauma through long-term exposure to material like this.

It’s been how I built my career. I’ve done years of work on the Decades series for CNN and they always dump those heavy topics — the tough topics — are the ones Inbal gets! So I get the AIDS and the war and the terrorism, and the rape and sexual assault and genocide and that’s been my career.

It’s not comedy. It’s not sitcoms. And it does take a toll. But you learn to compartmentalize. You learn to process in your sleep. Sometimes you do have to disengage emotionally and just really look at the story more clinically.

There might be some horrific murder and abuse and rape and death but you kind of have to still look at it as a story with a beginning, middle, and end — and with a resolution and with tension and with climax or conflict. I think once you distill it down to those pieces and work it out on a board — whether it’s on the wall or digital — it does help you to grasp the story.

And for me personally, those are the films that make it worthwhile. It’s so difficult making documentaries even when they’re not on dark difficult subject matters. It’s just a difficult process, and the hours are crazy. The intensity. The creativity. The kind of toll it takes on you — on your personal life. So for me when there’s an opportunity to tell a story that is really going to touch people and hopefully teach them something — change the way they view a certain person or subject matter, give them newfound empathy…

I’ve seen the effects that this important work can have. Brave Miss World has a website that has now 10 million visitors. It’s the number one Google search result when people are looking to share their rape story, so it has become an international central hub and an archive of testimonials by rape survivors and family members.

You can see when you tell an important story and you put your heart and soul into it and you feel the weight of the responsibility to do it justice that it can really impact people. And the more entertaining and palatable you can make it, the more people get to have that experience of interacting with your story.

I think we really accomplished that with Seduced — to have a story that’s fun. Perhaps it’s not always easy but it’s interesting and thrilling to watch. And it’s still very effective. And we’ve now started a website for the series and already it’s been getting a lot of e-mails and letters from comments from people who are recognizing the dynamics of coercion in their own lives — in their political system.

A lot of people have been drawing parallels to our political situation in this country. They’re also seeing it in their workplace and their romantic relationships in perhaps groups that they didn’t know or didn’t recognize as cults but now they’re realizing there were dangerous coercive dynamics.

So it’s incredibly rewarding to make work that has that impact. I see that as a responsibility and I am happy to take the brunt of the exposure to that material.

HULLFISH: On that note, Inbal, thank you so much for your time and for your expertise, and for sharing that with the many editors that listen in.

LESSNER: Thank you. Thank you so much.

LESSNER: Thank you. Thank you so much.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed, and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now