As television struggles to re-invent itself to stay relevant in a world increasingly getting their video fix from so-called “second screens” (tablets, laptops, smart phones or something not invented yet), one last bastion of broadcast television superiority is the live coverage of events. And nowadays, even that is being challenged by the online world.

Even though this year’s Super Bowl produced the third largest broadcast television audience in history (over 100 million viewers) the audience counts do not include online streaming. The Internet crowd is estimated to have set a new record of 1.4 million viewers per minute this year, almost double the previous year.

But on the production side, there hasn’t been a lot of change until recently. Even the shift to digital was more of an evolution rather than revolution. As the way we watch television changes, the way television covers events is also beginning to change thanks to the same Internet Protocol (IP) that feeds the box in your home. In fact, IP and the Cloud have become the latest buzzwords in live television production. Coaxial cable has been the veins and arteries of connecting television equipment since the beginning. Ethernet cable is creeping in and, according to some pundits, coax is on its way out.

IPTV was everywhere at the National Association of Broadcasters trade show this year. Companies that built their reputations providing hardware interconnected by coaxial cable for the industry like Grass Valley and Sony exhibited some form of IP solution that either eliminates coax or at least provides a transitional phase of hybrid coax and IP for both permanent facilities and for remote productions.

Television events are nearly all “remotes.” Any program or segment that emanates from a location outside the studio is considered a remote. Whether it be a county fair a local station covers live with two or three cameras, the Super Bowl covered with 70 game cameras or a highly polished and rehearsed awards program such as the Academy Awards, they share two conditions – they are live and they are originating from a truck that was somewhere else yesterday and will be somewhere else tomorrow.

Almost every piece of audio and video equipment is being re-thought and/or re-designed and in doing so, may radically disrupt the way television covers events. According a recent article in TV Technology, that’s exactly what Dutchview and Infostrada Creative Technology in the Netherlands are doing. Both companies are owned by the US company, NEP. Based in Pittsburgh, PA, NEP is the largest provider of mobile production services in the U.S. and owner of a number of production companies around the globe.

Rather than rolling out complete production facilities aboard large trucks as is done today, the Dutchview process simply eliminates production vehicles from the equation. Signals from cameras, microphones and communications are downloaded from the venue to a permanent control room in a central location where they are switched, graphics and effects added, the audio mixed and the final package made available for broadcast or streaming.

“There is really an opportunity to deploy IP across the production platform in smaller three-or four-camera events where it doesn’t make sense to roll a huge truck,” said George Hoover, chief technology officer of NEP in the TV Technology article.

The economy becomes obvious. Travel costs for most personnel and equipment would be virtually eliminated. Unlike the current model, permanent control rooms could be used to handle events from multiple cities on the same day. In regular venues such as football or baseball stadiums, camera and sound acquisition equipment could be assigned for an entire season. The camera crews would be the only personnel to travel to the venues or even be hired locally.

Remotes have grown as production capabilities have ballooned. The sophistication of today’s larger television events commands small armies of personnel with encampments of vehicles. Fifty-three foot tractor-trailor rigs with sides that expand beyond the legal highway limit house the equipment and personnel required to cover a show. The huge trailers carry so much equipment they approach the maximum highway weight in most US states. The bigger the event, the larger the compound of trucks and trailers.

It takes days, even weeks to setup and then sometimes up to several days to strike after an event. Then more downtime as the equipment travels from one location to another, not to mention maintenance costs due to the punishment the trucks and electronics receive on the highways and interstates. Many trucks must be on the road for several days and then unload, set up, produce the show and then load again to repeat the process. It is no wonder companies invested in covering televised events are looking for more efficient ways to do their jobs.

What a far cry from the way it all began.

Television cameras started going outside the studio as soon as the technology allowed engineers to load them on trucks and make them work when they got where they were going (no small feat considering how fragile and finicky the equipment was in those early days). Sporting events became a natural destination for early television experimenters. The first television remotes and the beginning of television sports coverage are synonymous with the beginning of television itself.

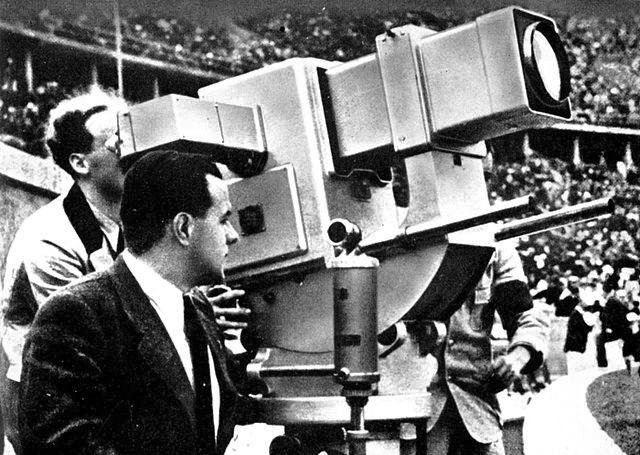

In fact, the first live coverage of a major world event was a sports event and coincides with the beginning of electronic television. It was the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, Germany. While these events were transmitted over the air, they weren’t intended for viewing on home receivers. Instead, they were transmitted to special viewing booths called “Public Television Offices” in Berlin, Potsdam and other German cities. The Nazi regime at that time didn’t see television as a home entertainment device but as a propaganda tool to be viewed communally.

The signal was only 180 lines (compared to today’s High Def 1080) at 25 frames per second. The propaganda obsessed government touted its technological superiority as the seventy-two hours of events that made up the coverage were shot with cameras from two German companies (Telefunken and Fernseh). However, their internal designs had roots in American sources, either Vladimir Zworykin from RCA or Philo Farnsworth, the inventor of all electronic television.

The British Broadcasting Company (BBC) was the first to build remote units or, as they are called in Europe, outside broadcast vans. The first official outside broadcast for the BBC was the coronation of George VI in May of 1937 using just three cameras. The unit was built by Marconi-EMI and established a configuration of three trucks. About the same time, Radio Corporation of America (RCA) began building the first “telemobiles” for NBC and borrowed the same arrangement. There was a mobile control room (MCR) unit supported by a transmitter van and a power generator van making the entire caravan self-sufficient.

That same year the British also did an outside broadcast of a sports event. The Tennis Championships and Davis Cup competition, broadcast live from Wimbledon using the newly commissioned equipment, may well be the first sports remotes done from a mobile unit. All the broadcasts were labeled as experimental by the BBC and took place a few months before the first RCA mobile unit was delivered to NBC in New York.

American television companies saw the value of sports, too. Games of any kind, from boxing matches to football games were popular because they provided a readymade source of interesting programming. As television receivers increased in availability, bars and saloons quickly installed them.

The owners correctly speculated that in a location where predominately male patrons already gathered, the new element of being able to see a game in a communal atmosphere and enjoy an extended feeling of being in the crowd at the game would draw in customers. Much of television’s rise as a major force in popular culture had its roots in these surroundings. Later, this pattern would repeat itself during the transition to color television.

But while the business interests used sports events as a way to stir up audience interest for the new medium, games also provided television engineers with situations to test how well equipment performed covering fast moving action where there was a lot of light, usually sunlight.

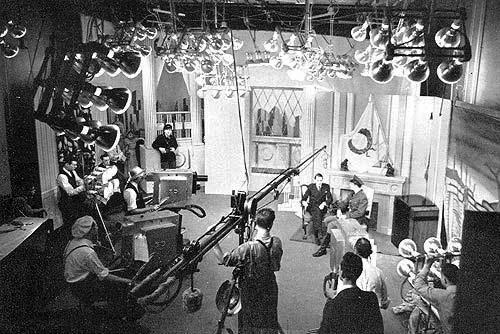

The amount of light was a major issue in early television. At NBC’s headquarters in the RCA building in Rockefeller Plaza (famously known as “30 Rock.”) where the radio network had many of its studios, one small studio was converted to television. The cameras used to capture television images at the time used the Iconoscope pick up tube that was full of video noise and required huge amounts of light (1000 foot-candles) to make an acceptable picture. So much light in fact that when the actress Dinah Shore made her first television appearance, the hot lights melted her mascara.

Of course production statistics such as Super Bowl 50 with its 70 cameras feeding 12 production trucks parked in a 65,000 square foot compound would sound like science fiction to the engineers struggling to put those first remotes on the air.

In 1939 NBC was solely a radio network that had just launched a television side of the company that consisted of one experimental station, W2XBS, in New York City (the same station destined to become WNBT, the first commercial television station in the US and later WNBC-TV). The station first went on the air in 1928 with mechanical television. It went off the air for a time as electronic television was tested and finally stayed on beginning in 1938 with a semi-regular program schedule.

The first RCA/NBC mobile units were delivered on December 12th, 1937. They took ten engineers to operate according to a Broadcasting Magazine article announcing them on October 1st, 1937. Each unit in the trio was based on a Mack truck chassis and was about the size of a large bus. The main control unit was equipped with two Iconoscope cameras. Engineers looked forward to taking advantage of bright daylight to make better pictures with the cameras.

During their break-in period, the recommended standard for television was re-defined by the Radio Manufacturers Association (RMA) (now known as the Electronics Industry Alliance) and Federal Communications Commission (FCC) under pressure from RCA for better television resolution. In June of 1938 the trucks were taken off line (and all experimental stations went off air for a period) to be modified to the new 441 line standard (later updated in May of 1941 to 525 lines).

https://youtu.be/kiDwxlPFYp8

After the short hiatus, the RCA trucks were back on the road to continue their experiments. Some programs were not for broadcast at all, but were demonstrations to influential groups meant to build up support for television. Such was the week the “Telemobiles” spent in Washington, DC, in February, 1939. At least 5000 government officials, members of congress, the FCC, diplomats and journalists made appearances in front of the cameras. The signal was then sent by closed circuit to the National Press Club.

Then it was on to the New York World’s Fair. On April 30th, 1939, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt became the first sitting president to appear on television as he opened the exhibition. A few days earlier, David Sarnoff, President of RCA, inaugurated regularly scheduled television broadcasts during another remote broadcast – the opening of the RCA Pavilion. The programs to fill this schedule would be produced under the banner of the RCA subsidiary, the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) even though it was estimated there were only about a thousand viewers in the New York City coverage area at the time.

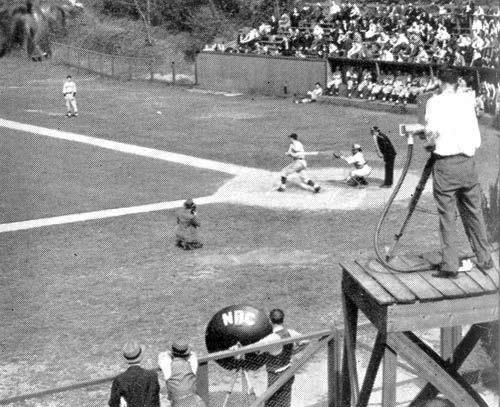

The very first US based television coverage of a sports event followed shortly afterward on May 17th, 1939. That first sports program was a baseball game between Princeton University and Columbia College from Baker Field in New York City in 1939. A 1944 alumnus of Columbia, Leonard Koppett, wrote about the historical event in spring, 1999 for Columbia College Today, “On the TV screen, one could make out the players but could barely see the ball, if at all.”

Only the second game of the double-header that day was telecast. Reportedly, RCA/NBC spent $3000 to produce the program. For some reason, coverage of the entire game was done with only one camera set up on a twelve-foot platform along the third base line. The camera had only one fixed focal length lens. Zoom lenses hadn’t been invented yet and a lens turret that would enable a cameraman to quickly rotate to a different focal length wouldn’t be added until later. Panning and tilting were the cameraman’s only options. There was no viewfinder. He framed his shots using guides on top of the camera that looked like converted gun sights and had to be talked into focus by the director.

As indicated by that first broadcast, the early days of sports television saw production at a minimalist level. However, NBC must have been satisfied with the results of the first broadcast because just a few months later, on August 26th, they broadcast television’s first major league baseball game. This time it was the first game of a double header from Ebbets Field between the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Cincinnati Reds not far from the location where the World’s Fair was still in progress.

The NBC “Telemobile” was back up to two camera strength for this game. Both cameras were stationary with one placed low and down the third base line near the dugout to cover the infield action and the other placed in a second tier box high above and behind home plate. Again, there was one fixed lens on each camera, but each was of a different focal length. One lens was a more sophisticated telephoto and offered the director a choice of shots for the first time, making for better coverage.

Writing later about the coverage of the game, the New York Times said, “The spheroid which appeared only occasionally as a white streak across home plate at Baker Field was clearly followed at Ebbets Field. The idea that the electric ‘eyes’ could never handle the scattered action of a baseball field faded at the Brooklyn diamond. It sparkled on the air.”

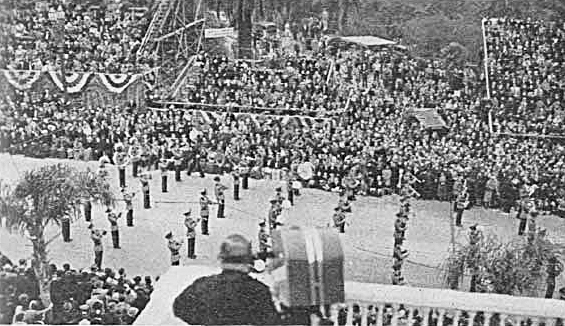

RCA/NBC was not the only American company experimenting with remote coverage. On the US West Coast, experimental station W6XAO (now KCBS-TV) in Los Angeles owned by the Don Lee Broadcasting System had initially gone on the air in 1931 with mechanical origination equipment. But by the end of 1939, W6XAO had all electronic camera equipment. Engineering Supervisor Harry Lubcke and his crew built their own two camera remote production unit and on January 1, 1940, they set up their cameras on top of a building in nearby Pasadena and provided the first television coverage of a Tournament of Roses Parade.

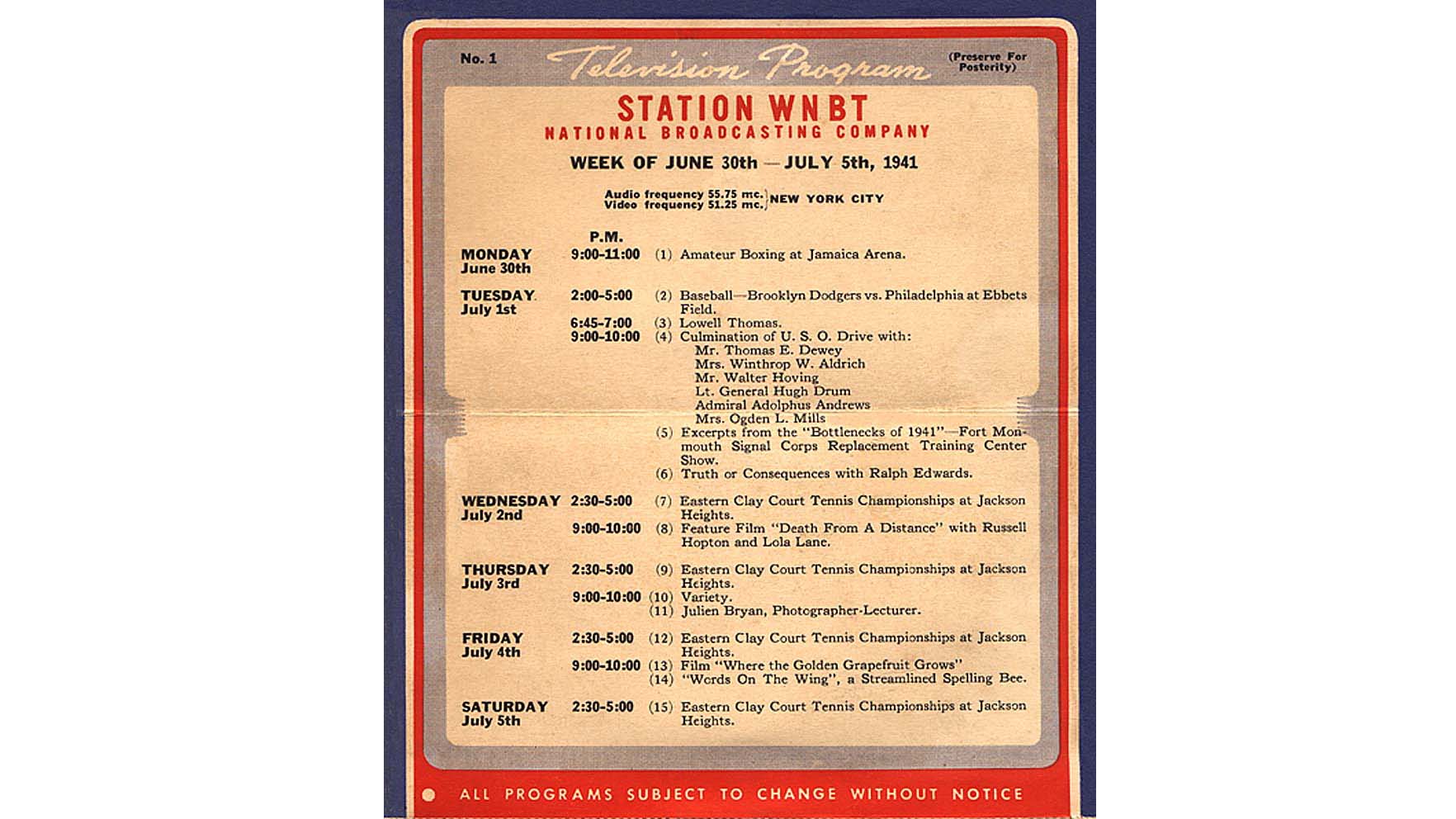

Commercial television was approved by the FCC to begin July 1st, 1941. As can be seen by the NBC TV schedule, the NBC remote unit was being kept busy as a live sports event was being covered everyday the week the station began commercial operations.

But in the next few months to come, further development of broadcast television had to take a back seat to World War II. British television and many US stations went dark. The ones that stayed on the air concentrated much of their schedules to war related activities such as civil defense training. The manufacture and sale of television receivers stopped as electronics manufacturers turned attention to the war effort.

In the second installment on television remotes, we pick up the explosion in the popularity of television after World War II and how the major networks took over the world of remote broadcasting only to turn around and give it up to independent companies.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now