Formatt Hitech Multistop, Kenko Variable NDX, and Tiffen Variable ND filters on a Sony 24-70mmm f/2.8 Zeiss zoom.

The Sony NEX-FS100 has no internal neutral density filters, and its telescoping 18-200mm lens doesn’t work well with matte boxes. Lens-mounted variable NDs are said to be the ideal solution: a single filter capable of 2 to 8 stops of brightness attenuation, thus replacing several conventional NDs.

Sony sent two variable NDs along with the FS100, and by sheer coincidence I had just ordered one myself, so I had a chance to try all three side by side. I’ve also explored one of them further on a PMW-EX1 and a DMC-GH2 EVIL (Electronic Viewfinder Interchangeable Lens) camera. Variable NDs are indeed useful, and are arguably the most important filter in your toolkit when shooting with electronically-controlled still-camera lenses—as long as you understand their peculiarities.

What They Are

Variable NDs consist of two polarizers, one atop the other. The front polarizer rotates, changing the alignment between them, typically going from a “min” position to a “max” position about 80-85 degrees away.

When their polarization axes are parallel at the “min” position, the filter cuts down light by about 1.3 stops. As you rotate the front of the filter, light transmission decreases, down to about 6-8 stops of additional light loss at the “max” position. In log-density terms, if we treat the “min” position as unfiltered (ND 0), that gives you a range all the way up to around ND 1.8 to ND 2.4.

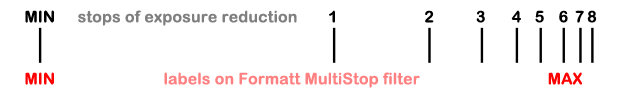

The filter factor, or exposure change, isn’t linear with angle of rotation. It takes about 45 degrees of rotation away from “min” before incoming light is reduced one stop, with additional stops of reduction coming with fewer and fewer further degrees of rotation:

Measured spacing of 1-stop adjustments in a quarter-turn of the Formatt Multistop. Tiffen and Kenko filters behave similarly.

Go past the labeled maximum position, all the way to 90 degrees of rotation, and the polarizer axes are orthogonal—completely crossed. In an ideal world, this configuration wouldn’t let any light through: you’d have ND ∞. In the real world, though, light squeezes through crossed polarizers in an interesting and angle-dependent way, as as you roll the filter past the 90-degree point you’ll see a “rolling X” or “X bar” (Tiffen’s term) artifact, as shown below.

In actual practice, there are of course two minima, 180 degrees apart, and two maxima, each at the midpoints between the minimum points. Some filters, like the Tiffen and Formatt examples, have a single min-max scale on a single quadrant of the filter; others, like the Kenko, quite sensibly label all four quadrants with min-max scales.

Since polarizers are used, the angle of the variable ND affects the rendering of polarized light, such as skies at 90 degrees from the sun; reflections in windows and water; glare bouncing off woodwork, floors, and the like; and any device with an LCD screen. If the frontmost polarizer in the variable ND is a linear polarizer, polarized light will be strongly affected, varying from full-intensity to almost total extinction depending on the rotation of that front polarizer. Some variable NDs used reversed circular polarizers for their frontmost filter; these have a much less dramatic impact on polarized light, showing only a gentle biasing of that light from blue to amber, depending on angle (samples below, but if you have a circular polarizer handy, you can see the effect yourself by looking through the filter “backwards” and rotating it).

Variable NDs vary wildly in price: 82mm variable NDs on B&H run from $50 to $600; on Amazon that same search pulls up filters from $16 to $500!

User reports vary equally wildly about which filters have unacceptable color shifts, too-limited adjustment ranges before “X bars” appear, or soften the image too much. Unfortunately I only had three variable NDs to test side-by-side, and only one to explore further. That’s why this is a quick look instead of a review.

Side-by-Side Test

Sony sent me a 77mm Tiffen Variable ND ($189 at B&H) and a 77mm Kenko Variable NDX ($450 at B&H). I purchased a Formatt Hitech Multistop ($230 at B&H). I tried them all out on a Sony Alpha 24-70mm f/2.8 Zeiss zoom mounted on an NEX-FS100 LSS camcorder.

I set the camera on its daylight white-balance preset, and used zebras to set my exposure to a consistent point (the two whitest bars on the DSC Labs Chroma DuMonde grayscale chart went stripy; this overexposed the chart slightly, but let me line up an iris/shutter speed combo than gave me the widest ability to halve or double exposures to compensate for the effect of the filters).

For each variable ND, I measured exposure without the filter, then put the filter on at its “min” setting, and measured the exposure change needed to compensate for it. I then opened iris or shutter speed up a stop, and turned the front ring of the variable ND to bring exposure down to my setpoint, repeating this procedure all the way to ten stops of attenuation (ND 3.0).

Filter effects: Filter name vs. stops (and ND #s) of attenuation.

All three filters in their “min” position cut the light by 1.3 stops, and all had the same affect on color, causing a slight warming of the image compared to the no-filter case. And, up until the “X bar” creeps in, all hold the same color rendition very consistently.

All the filters appear to use reversed circular polarizers as their front filters; the screen of the iPad I used to display filter data never went appreciably darker than its surroundings (with a linear polarizer, or a circular polarizer used un-reversed, it would go completely black at the point where the camera’s polarizer was at 90 degrees to the screen’s polarizer).

The “X bar” appears at different positions in the different tests, but that’s an accidental artifact, simply due to how the filters lined up when they were screwed into the lens.

The clip below shows you how the “X bar” got its name, as I roll the front of the filter through the 90-degree point, and also an extreme example of how overall filter alignment—not changing the angles of the two polarizers with respect top each other, but spinning the entire filter on its threads—affects the appearance of any differential darkening.

Varying the ND, and then spinning the entire filter.

The intensity and onset of the X bar, regardless of orientation, did seem to vary slightly between the filters (at least on this setup); the Formatt was usable perhaps a stop beyond the Kenko, which itself went maybe a stop beyond the Tiffen, though the actual point at which you’d draw the line as to their acceptability is up to you.

The filters also had different impacts on tonal-scale rendering and image crispness. The Tiffen was the most neutral; everything from deep shadows to specular highlights came though unscathed.

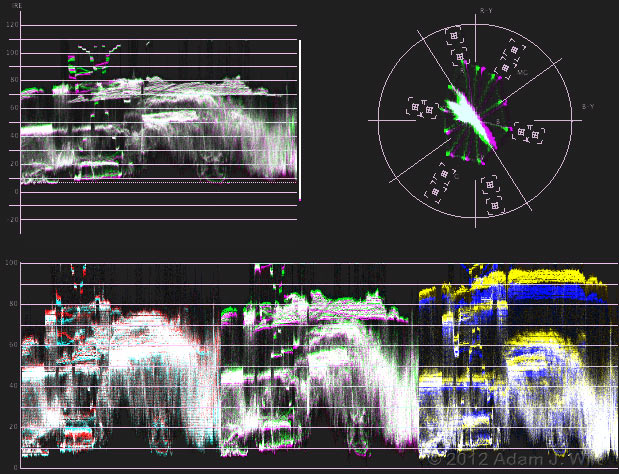

with (RGB) and without (CMY) Tiffen Variable ND filter.

In these grabs of the Adobe Premiere Pro ‘scopes window, I’ve superimposed the unfiltered scene over the filtered scene, reversing the colors of the ‘scopes for the unfiltered scene. While the overall waveform hasn’t changed much (the levels are just a bit higher as the magenta-to-green WFM separation shows, but that was due to my imprecision in setting exposure), the color shift is indicated by the slight movement on the vectorscope towards the upper left, and the strong reduction in the blue channel (yellow without filter, blue with filter) in the RGB parade.

The Kenko filter performed very similarly, but there’s a slight bit of flare on specular highlights; the reflections off the chrome on the cars blooms a couple of pixels more with the Kenko than without (the Tiffen showed no blooming at all).

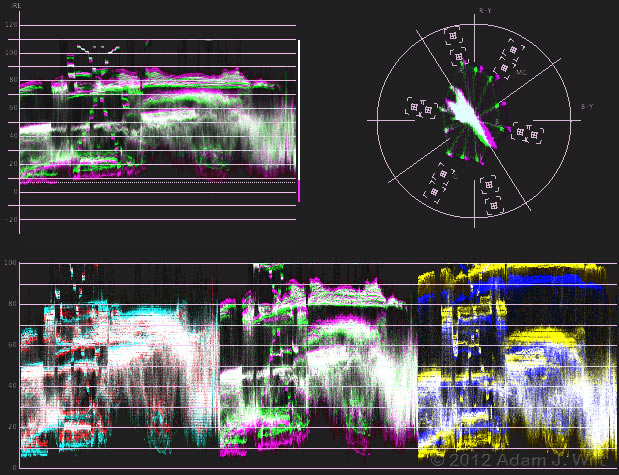

WFM, vectorscope, and RGB parade with (RGB) and without (CMY) Formatt Multistop filter.

The Formatt shows a noticeable compression of the tonal scale: shadows are lifted and highlights compressed to get the same overall exposure (though the color changes are almost identical to the other two filters). It’s almost as if the Formatt was acting as a contrast-reduction filter as well as an ND.

Next: deeper exploration; the secret weapon; pros / cons / cautions.

Deeper Exploration

Sadly, I had to ship the Tiffen and Kenko filters back to Sony along with the rest of their loaner gear, so I wasn’t able to test them in more detail—but I bought the Formatt, so I could do with it as I pleased.

I found that its contrast-reduction effect behaves sometimes like an Ultra-con filter, reducing contrast overall, and sometimes behaves more like a ProMist, with a diffuse halo of light around highlights:

Left: no filter. Right: Formatt Hitech Multistop.

(The perceived difference is probably dependent on there being a strong source of light in the image to show the halation in the first place!)

I put the filter on a PMW-EX1 to see what its effect on IR contamination might be. I set up a black cloth seat in sunlight along with some other test targets; the fabric is quite a bit darker and bluer in real life than it appears in an EX1’s picture. I white-balanced each shot on a gray card (with and without filter as appropriate), and compared no filter, filter on “min”, and filter with 7 additional stops of darkening dialed in:

The EX1 shows no additional IR pollution even with 8 (total) stops of added ND (ND 2.4).

It appears that this variable ND blocks infrared to the same degree it does visible light.

I mentioned that a variable ND having a reversed circular polarizer as its front element mostly affected the color of polarized light, instead of drastically changing its transmission. Here’s a typical sample shot, with the same filter setting, but with the filter rotated 90 degrees in front of the lens:

Two shots into the sun: same 2-stop attenuation levels, different filter rotations.

That’s as dramatic an effect as I was able to generate. While it’s not a showstopper, it may give a colorist some heartburn when trying to match shots; note that elements in shadow don’t shift color much while those illuminated by grazing sunlight vary quite a bit, so it’s not something fixable with a global, primary correction. Clearly, shooting multiple matching shots and reverse angles while using variable NDs requires a certain degree of additional care to ensure consistent color rendition. Just how much of an issue this is in practical terms, I don’t have enough experience (yet) to say.

Softening? It’s supposed to be worst at telephoto, so I tried shooting with and without the filter using long lenses: 200mm on a Canon 5D Mk II, and 300mm on the DMC-GH2. At first glance, the filtered shots were softer—but they were also much flatter, with that compressed tonal scale. Once I corrected the contrast in both shots to match, the results were much closer; once I turned off in-camera sharpening, which gave the contrastier no-filter shots an added edge (literally), any differences, post-correction, were closer still.

I’m not ready to say that adding the filter didn’t affect the sharpness of my pictures, but I’m not sure it added any more softening than adding any other two additional bits of glass in front of the lens would have done. And, of course, my experience with the Formatt doesn’t say anything about how other variable NDs perform in this regard.

Operational issues: The 77mm filter screwed directly into the Sony lens shown above, the PMW-EX1’s lens, and the 70-200mm and 24-70mm on the Canon 5D Mk II. On the GH2, I used a 62-77mm step-up ring for the 14-140mm, and a 67-77mm step-up ring with the Nokton 25mm and the Lumix 100-300mm. I much preferred working with the filter on the step-up rings: I was able to turn the front of the filter, or rotate the whole darned thing, much more easily when the filter itself had a larger diameter than the lens it was screwed into.

“X bar” unevenness shows up sooner (with less attenuation) on wider lenses than on narrower lenses, as the filter effect varies with the angle of view through the glass.

Many variable ND filters, the Formatt included, have larger clear apertures on their fronts than their filter threads would indicate (and may not have any front filter threads at all); this is done to reduce the chances of vignetting when used on wide lenses. Of course, this means you can’t attach additional filters in front of them.

Just for fun, I tried handholding various circular polarizers in front of the Formatt variable ND. A B+W slim KSM C-POL MRC filter worked as expected, letting me dial out polarized reflections as expected with little other effect. However, two Tiffen circular polarizers and a Rodenstock HR Digital Pol Circular MC gave me a very dark image, varying from a saturated deep blue to an equally dark and vibrant purple, depending on the angle between the filters.

The Secret Weapon

I’ve saved the best for last: variable NDs are smoothly adjustable, in a way that the apertures in electronically-controlled still-camera lenses aren’t.

Many stills lenses, even some that are sold as having smoothly-changing apertures for video use, only change stops in chunky, discrete steps. When shooting video with these lenses, whether on the Canon 5D Mk II, the GH2, or the FS100, I find I have to lock the iris to prevent step-changes in exposure during the shot (neither manual nor auto-exposure gives me smooth, undetectable iris changes with these cameras). In situations calling for exposure variation during the shot, I’ve usually fallen back on automatic gain control as the least disruptive way to operate; scarcely a recipe for elegant-looking shots!

With a variable ND on the front (light levels allowing, of course), my problems are solved: I can lock down aperture, shutter speed, and gain, and use the variable ND to smoothly and cleanly change the exposure, under full manual control, during my shot.

This is a game-changer: I can now execute clean exposure pulls with Canon EF, Sony Alpha, and Lumix lenses that simply didn’t allow such things previously. Let’s just say that a variable ND is going with me on any shoot using electronic-iris stills glass from now on.

You might find such a capability useful in your own work, too (grin).

Pros

- As little as 1.3 stops to as much as 6 – 8 stops of ND in a single filter.

- Smooth and continuously variable, allowing exposure control during the shot on camera/lens combos that otherwise don’t allow smooth exposure changes.

- No apparent variation in residual IR pollution, at least with the Formatt on the EX1.

- Consistent overall color reproduction as the density is dialed in, at least on the three filters I tried.

Cons

- Some polarization effect (color shifts on polarized reflections) even with reverse-circular-polarizer variable NDs; more extreme effects if the variable ND uses a linear polarizer.

- Polarization effects are angle-dependent; entire filter might need to be rotated to get the best image.

- Increasing the density increases the chance of “X bar” unevenness, especially on wider lenses.

Cautions

- Some variable NDs are reported to show additional color shifts as they’re dialed down.

- Filter quality varies between vendors; price may not be a reliable indicator of quality. You really have to try a filter to see if it’ll work for your needs.

- Variable NDs have at least 1.3 stops of light loss, so they’re less useful for exposure control in low-light situations (except, perhaps, on native-HD LSS cameras like the NEX-FS100 and Canon C300, where gain boosting is painless and unnoticeable until rather extraordinary levels are reached!).

See Also:

Review: Sony NEX-FS100 “Super35” LSS AVCHD Camcorder

Quick Look: Three new E-Mount Primes

Quick Look: Alpha A-mount Lenses on the FS100

Third-Party Accessories for the FS100

Disclosure: Sony shipped me an NEX-FS100UK, several Alpha lenses and adapters, two variable ND filters, two PL-mount adapters, and a PVM-740, which I returned at my own expense at the conclusion of testing.

I bought the Formatt filter with my own money.

No material connection exists between me and Formatt, Kenko, Sony, and/or Tiffen. No one has offered any payments, freebies, or other blandishments in return for a mention or a favorable review.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now