Mindhunter is one of those binge-able shows that has people talking. I spent a few days last summer at the Fincher production facility in LA where the show is cut and met one of the show’s editors, Tyler Nelson. One of the other editors on the series is Oscar-winner, Kirk Baxter, ACE, whom I interviewed previously for his work on Gone Girl. Both Gone Girl and Mindhunter were edited in Premiere Pro. (I was not able to talk to the third editor on the series, Byron Smith, who also cut the Netflix series, Altered Carbon.)

Kirk’s filmography includes numerous collaborations with director David Fincher. He was the additional editor on Zodiac. He also edited Fincher’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, The Social Network, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and Gone Girl. He won back to back Oscars for Social Network and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. He also cut episodes of Fincher’s House of Cards.

Tyler Nelson recently cut the feature Rememory, and was the assistant editor on Gone Girl, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, The Social Network and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. He was also an assistant editor on House of Cards and The Good Wife.

The series also featured an episode cut by editor Eric Zumbrunnen who passed away shortly after editing the episode he cut. Zumbrennen was a business partner with Baxter’s in the Santa Monica post-facility, Exile.

This installment of Art of the Cut is a little different. I spoke to Kirk and Tyler separately about specific episodes of Mindhunter. Kirk spoke only about his work on Episode 10, the season finale. Tyler talked about several episodes that he cut from earlier in the season, so we’ll start with Tyler’s interview and then move to Kirk’s.

The series is available on Netflix and it may be useful to check out Episode 2, 3 and 10 prior to the interview… or cue them up as you’re reading! The series has been renewed for season 2.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. The entire interview was transcribed within 15 minutes of completing the Skype call. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: One of the things I wanted to ask you about was the HUGE locators. The text that give the locations of the scenes…

NELSON: Haha! I’m surprised you noticed them. It was Fincher’s idea. I’m not sure which episode we were watching, but he said, “Let’s fill the frame with a big location card.”

HULLFISH: A few weeks ago I was talking to Billy Fox, who cut Only the Brave and we were discussing the great use of pre-lapping dialogue in Mindhunter.

NELSON: There’s a lot of talking in our show and using pre-lapping is a great way to continue the energy from one scene into the next. When you’re cutting from a scene where it’s mostly talking to another scene where it’s mostly talking, you want to remove the unnecessary stillness between them. But then again sometimes you want that stillness. There is one moment in Episode 3 where Holden and Tench are sitting and waiting to meet Wendy for the first time. The scene is three people making awkward small talk in a hallway, which leads into a five-minute conversation in Wendy’s office. The way that that scene was shot is the three characters walk down the hallway and exit frame. And then they open up the door to Wendy’s office. They all walk in, stroll over to their respective seats and then they sit down. Then there’s this moment. Nobody’s saying anything. Then finally, Wendy says, “I’m glad this worked out.” So instead of having this shoe leather, pre-lapping Wendy’s first bit of dialog in her office while they are walking down the hallway in the A-side of the edit and coming into the B-side on Holden’s line really keeps things moving along.

HULLFISH: There’s also a really nice push in to Wendy on her critical line. But everything before it was shot in these locked-off shots with these gorgeous, still compositions. Did that just jump out to you that “now’s the time for camera movement on this critical moment.”

NELSON: That was the crux of the scene. When Wendy expounds her analysis of what they can gain from interviewing all of these incarcerated subjects that really gets Holden’s attention. By adding that slow subtle push, it highlights everything that she’s saying. It’s a trick, but it’s a trick that works. And if you’re going to leave that scene with anything, you want it to be the information you learned in that moment. And we also added a little bit of a sting underneath it just to highlight it even more.

HULLFISH: There’s a spot in the basement of the FBI building where they’re mapping out where all of these killers are in jail around the country and then Tench gets this phone call, but the other side of the phone call seems very purposely masked… but not entirely.

NELSON: When I first got this scene, I had one of our assistant editors, Michael Vu, do some temp ADR of the other side of the phone conversation, just so I’d have the pace and the rhythm to edit to. I put some phone futz on the dialog and played it very low. You could barely hear it. That’s the way we had it in the edit for weeks. And then when we actually got the actor to record his lines we made it a bit more audible. Just enough for you to hear certain piece of information. “There’s been another attack.” “Fatality.” And even if you don’t hear exactly what Carver is saying on the other end of the phone, you still know what that conversation was about.

HULLFISH: There’s score, but there’s also great period music tracks that punctuate and illustrate and comment throughout the series. I noticed one as they’re going into the Sacramento Police station, for example.

NELSON: We had a great music editor on our show, Jonathan Stevens, who found some really amazing songs for us including that song. We used Feeling in the Dark by Dwight Twilley Band for that transition. I had never heard that song before, but Jonathan dug it up and it was perfect. It had this great energy that transitioned Holden and Tench from Shepard’s office in Quantico to the police station in Sacramento. On a mission to catch a murderer.

HULLFISH: While we’re talking about music, there’s a scene where Dwight – one of the killers that they catch – is scratching at a wound on his arm and music comes in at this specific point.

NELSON: These conversations with killers are so engaging that I really don’t think there’s a need to add much music. Actually, while we were editing, many of these scenes lived without music for a long long time. So when we started adding music, we used it during key moments like when Holden was learning something critical or making a connection with his interview subject – in this case Dwight. It’s just this subtle eerie music that creeps in while Holden starts getting into Dwight’s head.

HULLFISH: In that same scene there’s a really nice camera move as Holden kind of squats down to get on Dwight’s level and the camera follows him. Talk about choosing to use that move instead of whatever other coverage you had to work with.

NELSON: If there’s one thing we strive for in our editorial team it’s an element of perfection. And a lot of that comes down to making sure our camera moves are perfect as well. So that camera move that you are talking about is one where we are moving at the exact same speeds as Holden as he’s getting down to do his mind-meld thing with the Dwight. I feel like anything other than that perfect camera move to get Holden from a standing position to crouching – whether conscious or not – would take you out of the moment.

HULLFISH: But when you were looking at the dailies, did you see that move and say, “This is where I need to be at this point in this scene.”

NELSON: Well, when you’re cutting a scene like this you are going to have a lot of coverage to get Holden into that crouching position. We could’ve cut to a front on wide or medium shot for his crouch – or three-quarter. Covering him from the side was an option, but wouldn’t have done the scene justice. Over the shoulder is another option. The one that we used for his crouch just kind of sung — between the camera move and Jonathan’s Groff’s performance — that made it the star take for me.

HULLFISH: Another thing I liked about that scene was the build in pace as they start to interrogate Dwight in the alley next to his house. It starts to build into this staccato, quickly paced thing as it builds to the climax.

NELSON: What we needed to convey is that theses guys are beginning to work together as a unit. Holden and Tench aren’t two guys who just met anymore. They are starting to take on roles in these interviews and interrogations. Kind of like, “alright you play this role. I’m playing this role.” Tench plays the antagonist in this interview and Holden plays the buddy. He asks him about his life while Tench scoff at everything Dwight says. Then when they notice the scratch on his arm, that’s when it turns. They build up their intensity and start putting pressure on Dwight. I matched my editing style to emulate Holden and Tench’s barrage of questions. For that scene I didn’t want to hang on any single shot for very long, because there’s so much going on.

Conversely, there’s an episode that Kirk cut — I think it was episode 10 — there is this amazing scene with a local police detective. Holden and Tench are sitting at a bar and they are breaking down everything they know about this crime they’re investigating. Rather than showing Holden and Tench for most of this interaction we stay on a medium close up of this local detective with his eyes dancing back and forth taking this all in. You can see the look on his face – he’s never seen anything like this before. And it’s kind of amazing. But for this interrogation scene, I wanted to bounce around a lot so that Dwight started feeling more and more anxious until he finally breaks down.

HULLFISH: I loved the cutaways to reaction shots of the local detective who’s listening in on this whole interrogation and he’s starting to get what they’re doing and you can tell that he’s never seen police-work done this way and he’s fascinated by it.

NELSON: What we had to remind the viewers — who have likely seen a lot of these scenes before with modern detective shows. But Mindhunter takes place in 1977-1978, and these are ideas that are new to everybody including the people who are using them. So you want to make sure that you get all these glances from the local guy, Carver, and see how engaged he is by all of these new ideas and techniques. And he’s like, Holy Crap! I can’t believe what I’m seeing here.

HULLFISH: I love the fact that the detectives start to call them “sequence killers” instead of “serial killers” but you – as the audience – realize that that word hasn’t been coined yet. Talk a bit about the transition out of that scene from the Dwight interrogation to the news report of solving the case.

NELSON: It wasn’t scripted that way at all. Originally it went from Dwight breaking down to the guys cheering in the police station. We added the news reporter talking on TV later on to make it clear that they got their guy. I think we used about two thirds or three quarters of what was actually said by that reporter. By the time he says “after viscously attacking his elderly victims” the report gets drowned out by cheers which is a pre-lap into the next scene.

HULLFISH: And in that celebration scene there’s a moment where Tench – and the audience – just wish Holden wouldn’t talk any more.

NELSON: Yeah, Holden loves his criminology. Dostoevsky. Freud. He still loves the academia of it all, so any opportunity he has to hypothesize, he take it.

HULLFISH: I love discussing structure, and one of the moments that defines the overall show pace (not the pace from shot to shot) is when Tench is having a late night phone conversation with his wife about their son. It’s not critical to the plot. It has some nice character development, but it’s just a nice break for the audience to breathe and think.

NELSON: Those moments are important for the structure just like you’re saying because if you don’t have that moment of pause then it’s just one thing right after the other. This moment gives us a time to learn about Tench’s home life while giving us a nice breath before we get into an intellectual conversation with a mass killer.

HULLFISH: The scene with Kemper talking about killing his mother is another place where there’s a very careful choice of when to bring in score.

NELSON: That’s a similar situation with when we brought score in with Wendy. It’s underscoring all of this messed up stuff that Kemper’s saying and it puts us on the edge of our seats, hanging on every word. And then once we reach this incredibly revealing moment about why Kemper made the decision of putting his mom’s vocal cords down the garbage disposal – the scene is interrupted by a guard bringing in lunch and Kemper says, “Pizza! You guys…” It’s a bit of weird dark humor. I love it.

HULLFISH: Holden’s character has this interesting developmental thing where he talks with confidence about things that he gets completely wrong, but then he realizes how little he understands and he really wants to understand it better.

NELSON: That’s Holden’s path through this entire season. He’s stumbled upon this new way of thinking about criminology and behavioral science and we as viewers are along for the ride. Like the whole thing about them calling them “sequence killers” instead of serial killers. It’s a way to remind viewers that this takes place in the late 70s before any of this was known – even to experts. Viewers in 2017 have a pretty good understanding of the methods Holden is learning along the way, but it’s fun to watch it happen – stumbles and all.

Like you were saying, he talks a good game and he’s so confident in his delivery even when he makes mistakes. Like in Episode 2 when he claims the killer must be a teenager who wouldn’t bathe because that’s what his mom would want. They all kind of accepted that theory and follow that lead. But then he learns something else in a conversation with Kemper and it changes his perception of who the unidentified suspect might be.

HULLFISH: There’s some really nice sound work that really brings the scenes to life, like a scene outside of a doorway at Quantico where you don’t have much visual reference to where they are, but you can hear the sound of a firing range in the distance.

NELSON: That was an element of sound design that we put in. they are at the FBI training facility and there are firing ranges all around. If you listen closely when they’ve been moved into the basement, you’ll hear all the sub-terranean stuff you’d hear down there: the heaters, pipes, and ventilation ducts and echoey movements from the floors above. Because at this point they are not taken seriously so they’re moved out of sight.

HULLFISH: I also loved the realism of a scene they shot in a bar where you can BARELY hear the discussion between the two principal actors.

NELSON: Like a real bar! I didn’t cut that scene. You’d have to ask Kirk about that. One of the things I like about all of Fincher’s work is he tries to make the environments real. Going back to The Social Network when Mark Zuckerburg and Sean Parker are talking in that dance club, it’s a similar situation. You can barely hear what they’re saying because they’re having a conversation IN A DANCE CLUB. So in this case it’s two guys hanging out at a college bar: it’s probably not going to be very audible.

HULLFISH: I love the choice of music throughout the show. Tell me about the end of that scene where they’re walking with Wendy across a courtyard in Quantico and a track comes in… what drove the timing of starting that track?

NELSON: I had a hard time finding a song for that scene, but ultimately we ended up with a pretty solid choice with David Bowie’s Right.

The choice of where to bring it in was dictated by how long their walk and talk at the end was. We slowly let it creep in just as they started walking and there’s this nice crescendo building up to the lyrics, which was the perfect transition point into the credits.

HULLFISH: Got it. There’s this term that radio DJs use called “hitting the post” which means that they finish their intro to a song just as the first word of lyrics comes in. That was like that. So it’s just back-timed.

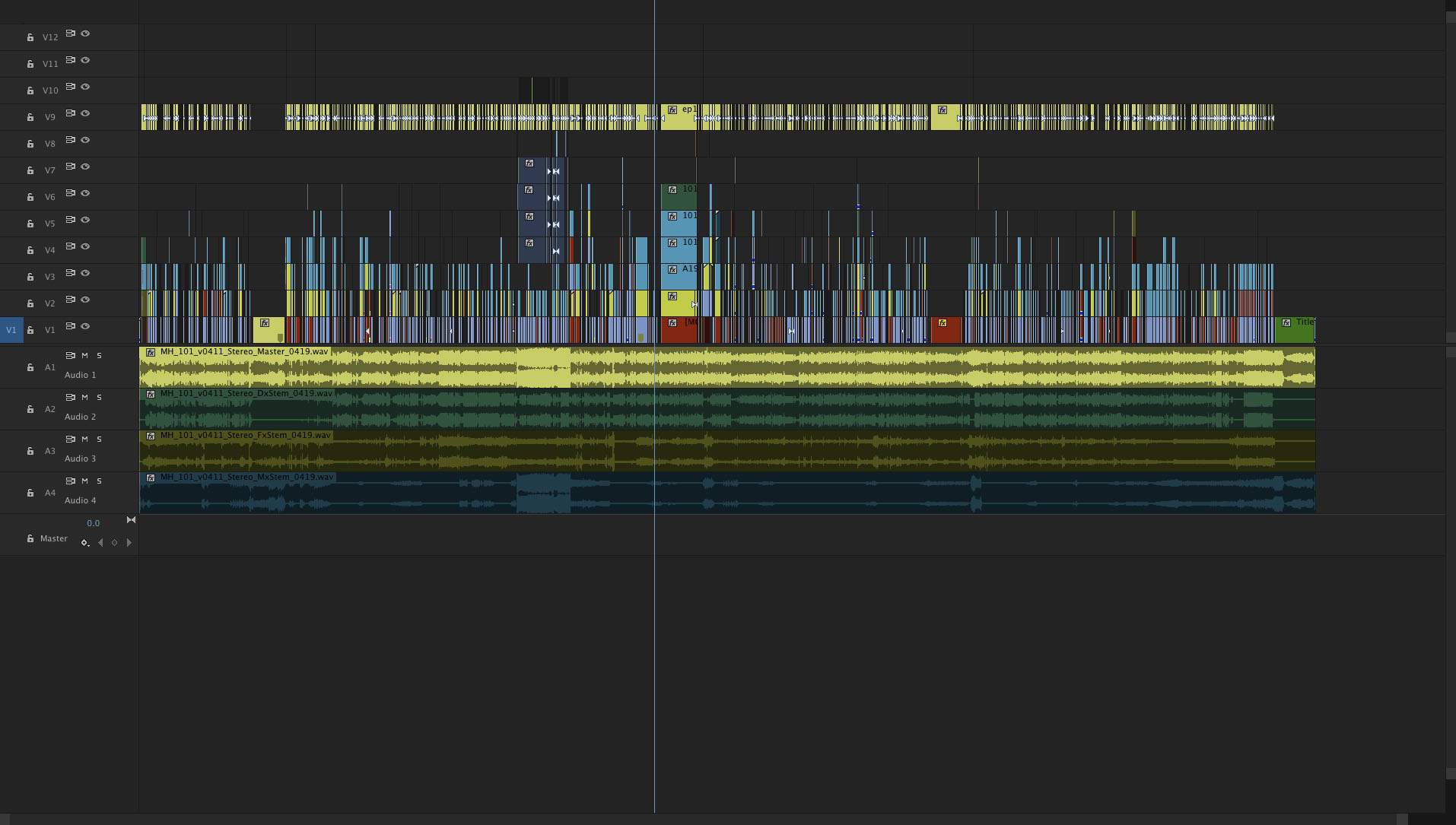

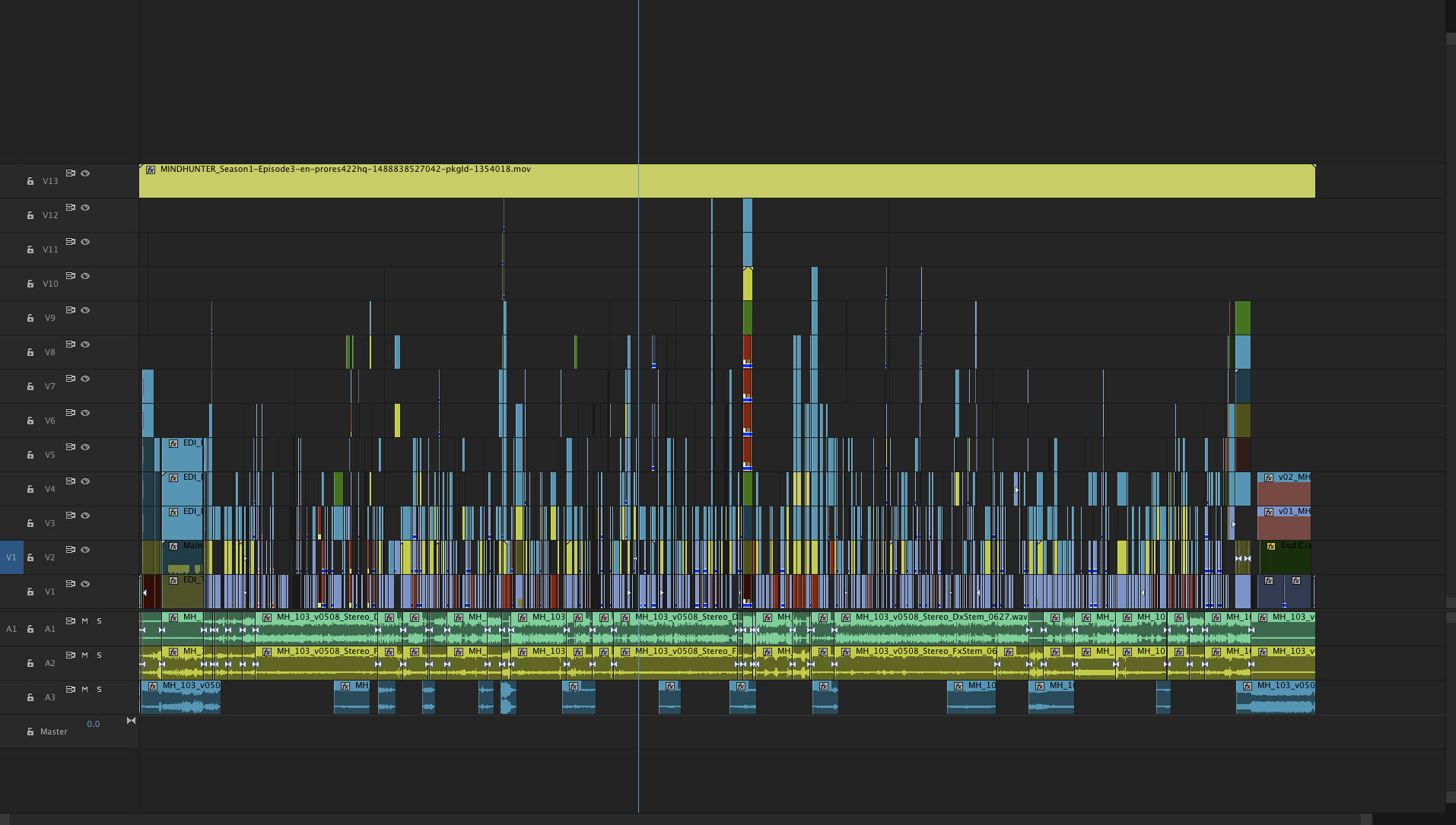

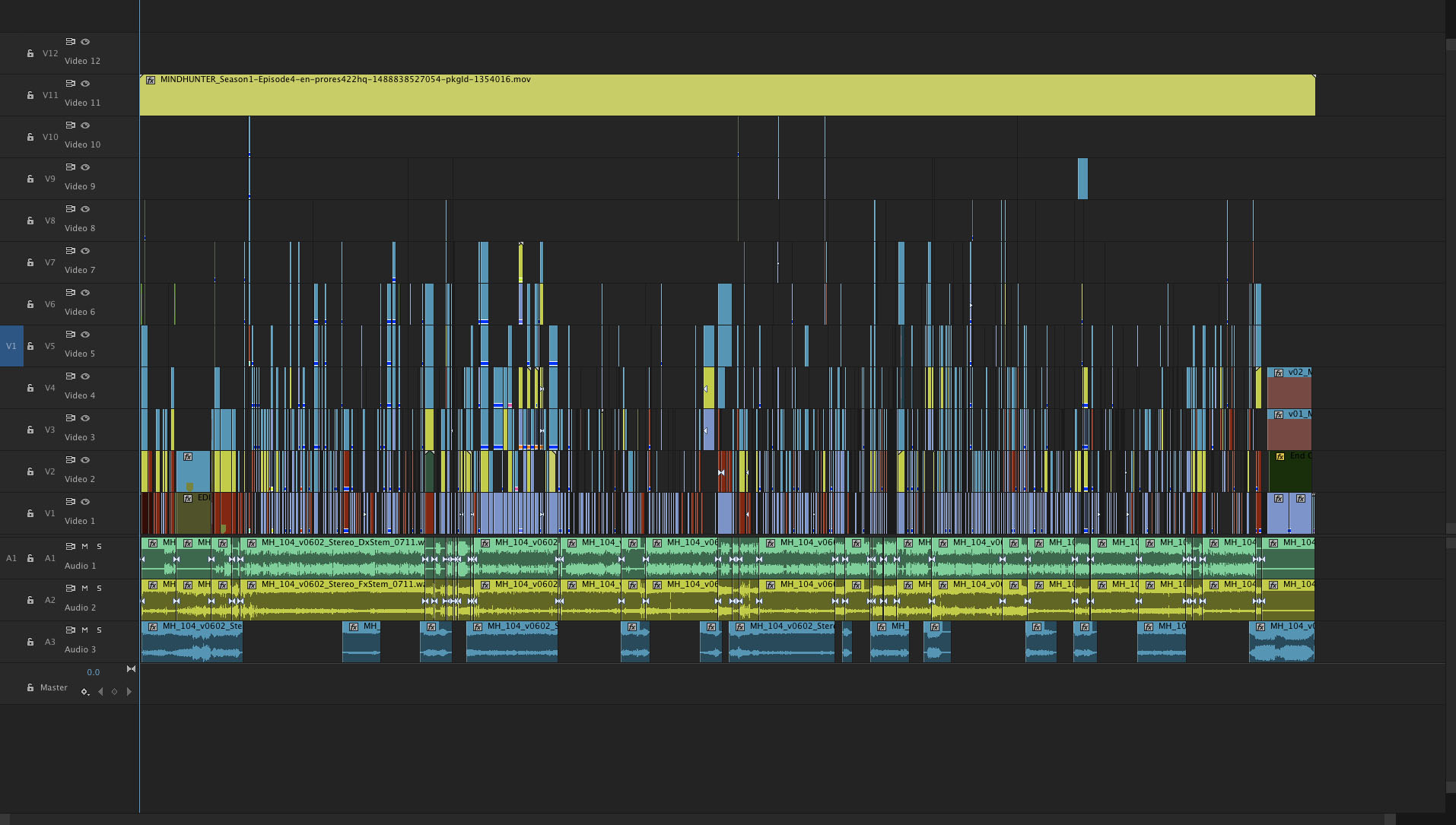

Tell me a bit about using Premiere and how you’re liking it.

NELSON: The first time we cut anything on Premiere was a Calvin Klein commercial back in 2013. Kirk was the editor and I was his assistant. That was our test project to see if Premiere was a viable option for a feature film. At that time, we didn’t know what feature film David was going to direct next, but we knew that we were going to have to move on from using Final Cut Pro 7, which we’d been using for years. Our experience on that commercial told us everything we needed to know about Premiere: the pros and the cons. We had a pretty good relationship with the Adobe Premiere team, so we put up a big list of feature requests and bugs and said, “this is what we need from Premiere to use it on Fincher’s next feature.” They were very amenable to everything on that list. They wanted to make it work. So once Gone Girl came around, we worked very closely with the Adobe engineers to make sure that project went smoothly. And it did go pretty smoothly.

Once Mindhunter came along we continued our relationship with Adobe. I don’t think it was ever a question of whether we’d work on Premiere, it was just how can we make our experience with Premiere better. During my down time between projects, I provide feedback. As does one of our assistant editors, Billy Peake. And most of the editors at Kirk’s commercial editorial company cut on Premiere as well. So we have all of these editors and assistant editors that report bugs and request features to the same Premiere engineers that helped us on Gone Girl with the goal of improving the software.

I was on a panel a few months ago with Billy Fox and one of the questions was: when you guys are working in Premiere, is that the off the shelf version or is it a custom build? I hear questions like that a lot. People say, “well they were only able to use Premiere on a feature because they were on a custom build.” Yes we were, but the custom build that we were battle testing day after day eventually gets released to the public. Adobe has been really amenable to the feedback that we’re giving and they’re making great strides to make sure that they stay a viable competitor in this market. They’ve come along way in the past few years. Avid is still the industry standard, obviously and they’re a solid choice. And I know that’s Resolve is looking pretty impressive too. You came over and gave me the rundown on Resolve last summer while we were cutting Mindhunter. I haven’t used it on anything yet, but I think it has potential. But for the time being Premiere is our bread and butter. We’re very happy with it.

HULLFISH: Are you using any of the new collaboration tools they’ve recently added to Premiere?

NELSON: We’re interested in using Premiere’s collaboration, but we just haven’t done too much with it because by the time that the shared projects workflow was available to us it was too far along where it would be beneficial. I’m working on a project right now where it’s just me so the shared projects thing is kind of a moot point. We still need to do some research on that but I think when Season 2 comes around it will be probably on a shared project workflow.

HULLFISH: What’s the workflow in Premiere with your assistant editors without using collaboration?

NELSON: All media that’s recorded on set: R3D files and broadcast WAV files are processed on a FotoKem NextLab cart and then imported into our custom database. That database parses and organizes all of the metadata that was recorded throughout the day so that we can do some fun things with that data. Once one of our assistants is working on dailies, they use that database to produce a custom XML, which they then import into Premiere. That XML creates a project where all of the clips are renamed to match the slate, and those clips are automatically organized into bins with scene descriptions, multi-clipped, and strung out in sequences the way we like them. Also, any script notes that were made get applied automatically, so the amount of time it takes for our assistants to prep dailies is extremely minimal.

I like to select in sequences rather than bins, so after the assistants trim before “action” and after ”cut” I’m ready to start working. I have a sequence for each setup with all of the takes laid out in reverse order, with the assumption that the last take they shot was the best. Though if the director had a star take that goes to the front of the sequence. It’s super easy to just watch it down and if I find something I like, I lift that to V2. Once I do this for each sequence, I put all of the selects from V2 into a new sequence and put is in contextual order. This is my selects sequence. I usually watch this down once or twice and start slimming it down. Depending on the complexity of the scene, I might duplicate that sequence and make a slimmer super selects sequence with sketches of different editorial approaches to moments within the scene. By the time I’ve done all of this prep work I have a really good starting point for my first edit of that scene.

HULLFISH: At the very beginning of Episode 10 – the finale – of season 1 of Mindhunter – is a scene in the airport continuing into arriving at a police station. The scene is pretty expositional as they’re walking and you put a great music track under it to kind of move it along and give it some pace. You also used a series of kind of swish pans that I’m assuming were created in post.

BAXTER: I can’t remember the name of the track now, but it was from 1978. We were strictly keeping to the era so the music put you in the time frame of the show. That whole scene is about Holden being a motor-mouth-expert – so he controls the pace and having a driving piece of music seem in step with him.

David wanted to explore those flash wipes when you’re inside the terminal and leaving the airport. I wasn’t too into the idea at first because we hadn’t used that language anywhere else in the series. I experimented with it and it worked, but because that music track carried all the way through into the interrogation room it made sense to make a theme of those flash wipes as long as that music track was playing. Then David gave me the task of going back and applying the flash wipes to other episodes where appropriate. It became something we used whenever we were leaping time so it wasn’t so individual to episode 10.

HULLFISH: The airport is all wide shots and then we finally get to close-ups when we get to the evidence room.

BAXTER: With those walk-and-talks David is going to shoot them pretty basically, so there’s not a lot of coverage. It’s mostly picking the best take and I’m going to overlap wherever I can to keep things dancing along. Then when we get into the evidence room, I have a whole bunch of angles to intercut and play around. It was just luck where that train whistle landed on the rock. After I saw it hit once I had to protect that moment. So as the ebb and flow of editing happened, I always made sure that train whistle sync stayed exactly on the rock because it was just so enjoyable. I love shit like that.

HULLFISH: Several times you use pre-lapping of dialogue. One of those spots in this episode — 10 — is where they’re walking the suspect into the interrogation room and as he is walking in you’re already hearing the interrogation under way.

BAXTER: I’ve always been a fan of pre-lapping to move things along. In general I try to let the dialogue lead the picture edits. Most of the time if I’m in a scene of a group of people talking, I’m going to hear the line start before I cut to the person talking. I rarely cut to someone just before they speak. There will be times that you want to or need to, but I find if you always cut for the line it ends up looking like a porno. So I like prelapping: not just getting into scenes, but with forcing the picture cut. then searching for the moments when I’m on someone NOT speaking, or holding on them for a beat before their line starts etc. It’s that little ballet that you’re always seeking out so you’re not constantly cutting on the line, which becomes a bore to watch.

HULLFISH: One of the places where you do that dialogue cutting to great effect is in the scene where Wendy and Holden go to visit the DA in Rome, Georgia. As you mentioned, very often, you are cutting to the audio of the person speaking before visually cutting to them. So that’s the idea that when someone says something it takes a second before you turn to look at them. But there were a couple of places especially in that scene where you would cut to — for example — cutting to Wendy before she speaks so you see her reaction to the end of a statement by the DA.

BAXTER: Absolutely. If you’ve got a reaction when an actors face sort of opens up to the information that’s landing on them, that’s something you are always hunting for. Especially so it’s not always this rhythm of “let’s cut before we speak”. You’ve got to get your off-beats in there, your “reggae.”

HULLFISH: So are you a ska editor?

BAXTER: You just try not to be too formulaic. Many of these rules have been established: what’s effective and what’s not. For example, I usually like to be wide when people are moving around the room. You want the audience to understand where you are. It can get messy following movement in close up. I like to move closer in as we get to the point of a scene, and then deliver your punch-in-the-nose in a big fat close up, but there will always be examples of throwing all of that out the window and doing the opposite. That’s the chaos of film making, it’s constantly making you rethink your approach based on the material.

The scene that you mentioned was written for everybody to be cutting each other’s sentences off, so as an editor, you’re just trying to enhance that as best you can. But the tastiest parts in that scene for me is Holden listening. He does these little things with his mouth, and a disappointed head drop as they get shut down. That to me is the juice!

As I select a scene, I’m looking for all those moments. The subtle reactions that can shape a scene. You can build all the meat and potatoes of the dialogue, but I’m looking for the opportunity to pepper it all the other fun stuff.

The other scene that’s like that is when Holden gets interrogated by the Behavioral Science Unit at Quantico. I adore cutting those sorts of scenes when you’re given all angles, the wide shots, the front angles, the side raking three-quarters, eyelines for every actor. David gives you all of it and then it’s a dance of how to present it all. Do you want to stay on someone while they’re listening? Do you want to do that little pre-lap before each line? Do you want to hold on someone before they speak? I typically try to get it all in there and make sure that every angle is used. You build it almost like an action sequence where we’re going to come in for that key moment. I just adore doing that stuff. I love it — as long as you’ve got the material, as long as you’ve got the angles.

HULLFISH: There was a wealth of angles… not just the basics but really interesting things to choose from to mix it up in both the DA scene and in the scene where Holden is being interrogated by the BSU at Quantico.

BAXTER: When I go through and watch everything, at first I have no clue how I want to construct it. It’s the chore of selecting the hell out of everything, putting aside the best performances and angles for every beat that starts to inform me, unless it’s a oner (a scene shot with only a single angle), I rarely have a clue what I’m going to do. You just start doing it. You follow your nose and stop when you believe it.

HULLFISH: Are you following your nose when you’re editing or are you following your nose when you’re watching the dailies?

BAXTER: When you see stuff that’s bubbling up to the top, that’s when you start creating a path. If David’s got a camera that’s going to slowly creep in, I’ll know, “Oh, during those lines, most likely, I’m going to be here.”

The choreography of how you’re going to present a scene, even the simplest of them – that, to me, is the most exciting part of what I do. Going through multiple performances to choose the very best one? That sort of stuff is homework. Once you’ve got the best of each thing then it’s really how you choose to present it with all the tools in your tool box. That’s the part I get thoroughly excited by. Once that’s done it’s going through for weeks of perfecting and changing syllables in people’s mouths etc. Things can improve in that last 5 percent where something good can become great, but it’s the initial creation and the blocking out of it all that is the joy. That makes me turn up again and again.

HULLFISH: I would think that one of the scenes that would have been like that to choreograph was the interrogation of the child murderer. Eyes darting back and forth, shocked reactions development of characters.

BAXTER: The content of that scene is so sick and that’s something I don’t control, but how do you enhance it? Someone like the local cop — David is going to film him from every angle from start to finish in the scene so I can cut to him at any moment for any line, so I’m going to go through all of his performance for the most impactful beat, and it had to be the moment where Holden’s saying, “Isn’t this 13 year old girl sexy?” And the local cops face looks incredulous. which starts a chain reaction of looks to each other. They are all the highlights for me. They’re the moments that you want to get in there and play all the angles off each other, squeeze as much juice out of it as possible. I’ve also got the cop that’s watching from behind the glass, I’ve got a handful of angles of that guy shot from start to finish of the scene, and what part we use is the game. Holden’s questions, as outrageous as they are, you may only need to HEAR those and you play off everybody else responding, and that heightens it all. I LOVE all that. That was a great scene to cut.

HULLFISH: I felt like so much of the motivation for cutting in that scene was on the eye-lines of the actors — on their looks to each other.

BAXTER: Yeah. Following eyelines. David gives you the angles of the eyelines. So it’s cutting dialogue scenes like action scenes. Love it.

HULLFISH: There was a music cue that came in when Holden picks up the girl’s yellow jacket.

BAXTER: That was the moment Holden goes for it. Everything else is preamble leading up to that point. The music’s heightening the change in the scene. Holden’s manipulation. The camera slowly tracks in with Holden, I hold on that as long as possible to cast the spell and hold back from getting into coverage. If you sit on it too long then the tension may fade away. Then it’s sort of a mathematical question of when are you going to hop off this slow push in and get in to coverage – where you can really manipulate the pacing. Then you can start doing — with Holden and Tench — kind of left punch, right punch. Once you get into their coverage you can really get them overlapping and finishing each other’s sentences and getting super, super tight.

Funnily enough, I received the dailies for that scene in the interrogation room BEFORE I had the scene in the evidence room. The way the interrogation scene was staged: he picks up the jacket and his dialogue is talking about the jacket, so I cut it as if the jacket was the point, not the reveal of the murder weapon, the rock. Then I see all these long push-ins to this rock! So I re-analyzed the material again and realized that I had completely missed the point. I restructured it so that it’s all about the reveal of the rock. But for the first couple of hours that was lost on me. I’m quite pleased that I never sent my 1st cut to Fincher.

HULLFISH: One of the ways that an editor understands the director’s intent is seeing those special shots — like a push in on a rock — that MUST mean something because of the way it’s shot.

BAXTER: Yes. All of the attention David can get for the amount of takes he shoots is misplaced, the point is the coverage, the angles, he shoots what the scene needs. It’s not like I had a pile of shots of every object in the room. It’s specific. Every angle had a purpose and it becomes a chess game of how to utilize them all to the best degree. So with David, I’m never fixing a scene, I’m always just enhancing it. So you don’t have to invent the purpose. You just have to illuminate it.

HULLFISH: Well THAT’s a great quote.

You follow the fairly intense interrogation with the fast-paced bar scene and then you have this almost 90 second oner with the shopping cart. I assume that was planned by Fincher and that you had no other coverage for that oner in the supermarket with Holden’s girlfriend?

BAXTER: Nothing. He’s made that choice. When you’re in that phase of dailies pouring on you every day and you get a oner for a scene it’s a gift, you can edit it quickly!” But it’s never quite that simple because in order to make a oner perfect there are a lot of takes – so you’re sort of juggling between the best five or six choices, and once you land on what the best one is for performances and for camerawork, now it’s, “Is that the best line? Can we pop a better one in?”

It can become the same as a scene that has coverage, putting together every read in a row to help decide what the best audio reads are. Then you start dropping them in and post-syncing lines.

HULLFISH: I know a lot of editors will understand what you’re talking about, but to clarify – you’re saying that although it’s a oner, there’s only a single shot all the way through, but that every single dialogue line that you’re hearing can be from a different take.

BAXTER: If you’ve got 15 takes there’s a good chance you’ve got half a dozen reads that you’re going to perfectly place into people’s mouths. It’s unlikely that two actors playing off each other for a scene that has 20 or 30 lines will nail every single inflection. So you look for the weakest links and improve them.

HULLFISH: Like you said, just because it’s a oner doesn’t mean you don’t have to work.

BAXTER: I try to keep up with camera as best I can while David is shooting. I’m usually a few days behind, so in that initial phase of assembling, a oner is a great thing because it lightens the load, but eventually you come back to pay the piper, when you’re at the stage of perfecting.

HULLFISH: So all of the dialogue replacement you don’t do while you’re trying to keep up with camera.

Talk to me a lot about sound design. There is always an active soundtrack: phones ringing, people talking, firing ranges, even the freaky sounds of the basement.

BAXTER: David really wanted to push that they’re in the basement.

There’s two things about Quantico that he mentioned to me after he researched the place in person: 1) He was intrigued by the constant firing of guns. There’s only one scene in the series where we see the firing range, but even when you’re in offices in the building, you’re hearing this pop, pop, pop in the distance, which I loved.

I never worked with those sounds in the cut. That came at a later stage, but I adored that kind of enhancement because it just constantly reminds you of what is at stake with being an FBI agent.

The second thing was the basement. It’s so many flights down. David wanted to enhance the banishment to the basement by creating the groaning sounds that buildings of that size do when you’re going to be that close to all of the mechanical rooms, and pipes, less officey sounds and more “belly-of-the-beast.”

Next season it’s going to be helpful because now we have a library of all the sounds. David Fincher and Ren Klyse have a longstanding relationship and Ren supervised for this show and set up the audio team and he gave us a lot of tracks from Zodiac that he’d saved that were from the right era: a lot of office stuff, exterior noise, street sounds, the right cars, the right era for phones and airconditioning sounds, etc., etc. So we used a bunch of that to get started.

HULLFISH: I really loved the pacing of the scene with the DA in Rome, GA. They were talking over each other and there was such a great selection of different shot angles. Clearly David gave you plenty to work with.

BAXTER: Tyler Nelson assembled that scene for me so I picked it up in pretty good shape and mostly worked around the point of the area where Holden was listening and all his reactions. I just got to pop those cherries on top.

Halfway into that scene there is a wide shot that had a slow push-in that began as Wendy goes for the kill. It was interesting to come out of the coverage and bounce all the way back to a wide for that moment, then slam into Wendy’s closeup.

I think that was constructed that way because of the choices David made when he was filming. We could have thrown away those choices and presented something else but that was how Tyler initially cut it and I thought it was very effective.

HULLFISH: One of the things that seemed like it could have been really tricky to edit was the phone call Holden received about Kemper trying to commit suicide. There’s a lot for Holden to process and in the middle of it all there’s a lot of background action happening around him that he’s also trying to track and that the audience is trying to follow as well.

BAXTER: It was tricky but it was thought through. I had everything I needed. Because that scene is a multi-layered dance, I’m not able to control pacing to a degree that I normally would. So Holden’s response-time to the person on the phone is slower than I would typically cut him.

We could have expanded what was being said by the doctors Voice over so that it is more wall-to-wall but it suited Holden at the time to be a little slack-jawed. There’s quite a lot of pausing in there before he reacts and responds which then highlights that door closing and his jarring reaction remembering that he’s on the phone. It’s the confusion of multi-tasking.

HULLFISH: That was my take. That the pacing of that scene was that he was a little slow because one) he’s distracted by what’s going on around him and two) he’s stunned by what he’s hearing.

BAXTER: It’s interesting that, because if I’ve got say six seconds between Holden saying one thing and the next, all of the choreography of the action is dictating where I can cut and perhaps I’ve got a two second response from the person on the phone, so I can place the audio response on the phone anywhere within that six second gap. It’s amazing how much difference it makes where you place it. If you put it earlier, then the person on the phone’s trying to push the conversation forward and Holden’s wait time is too exaggerated. If you move it back, Holden’s pushing it forward and the person on the phone’s distracted, ten frames one way or another has huge impact on whether the scene’s feeling slow or you’re in that sweet spot of Holden’s performance.

HULLFISH: Coming out of some of these intense scenes are nice reflective moments as well where you can really breathe, and those are also places where I could really appreciate the sound design making those moments continue to live and feel alive.

BAXTER: Yes. It’s wonderful to get those gaps when everything’s not just wall-to-wall and you have those moments where things can be cinematic and for the sound designers to get to shine and to let music push its way through.

HULLFISH: Another place where I liked the music selection was after Holden’s scene with his girlfriend on her front porch and then it cuts to Quantico the next day and the music seemed more about allowing the audience to process the information from the previous scene than it really was about something appropriate for the location and action on screen at that time.

BAXTER: Yes. The music did belong to what was before it. That track was one that was based around Debbie and Holden.

HULLFISH: There’s another place where music comes in, it’s a great Zeppelin track, and I was interested in where it came in, specifically. It starts as Tench tells Holden, “I told them the truth” after the interrogation. That’s right where the music comes in and you took that track from that point all the way through a montage to when Kemper speaks at the hospital ward.

BAXTER: I found that track and I think it is one of my favorite, proudest offerings from this whole series. If you’ve got storytelling that’s happening without dialogue you can get a track and really highlight it. Now you’ve got time for lyrical content and it doesn’t just have to be score. The lyrics seem to apply to what Holden’s mood was and it was a bulls-eye for the era. It worked because it had this intro piece that leads Holden to Kemper, then I was able to reprise the track when Holden escapes Kemper.

The placement of the music using a long intro and then returning to it when Holden bursts out of the room later to close out that episode was initially David’s idea, but with a different track. I put the LED ZEPPELIN thing in there. I’m still patting myself on the back for that one. Honestly, it just made me so happy.

HULLFISH: When I’m starting a feature, I will immerse myself in the music that I think I’m going to use — listening to soundtracks when I’m going for a walk, or in the car, or in the shower….

BAXTER: Embarrassingly enough, I got that track from doing yoga. Not that specific track, but a Led Zeppelin track was playing as I left the class. Zeppelin was in my head all the way home and it got me to thinking, “Why the f**k haven’t we used Led Zeppelin?” I start researching and I go to the right album for 1979 and it’s Physical Graffiti so then I think, “Okay. What song is the best song?” And that’s when I hit on “In the Light” and it was perfect because it had that slow intro, and I had it in the back of my mind: Let’s find a track that requires a big slow intro and then returns big after Holden escapes the hospital room. That track was hand-in-glove. I remember after finding that track, thinking how valuable it is to have processing time in your life, so you’re not just going from task to task.

HULLFISH: I loved the end of that scene with Kemper and Holden. It’s just a great construction of moments building on each other in meaning and tension and emotion. Both of them noticing the orderlies that are there — but then they leave — meaning that Kemper is alone with Holden.

BAXTER: At first I was a little confused with what to do with the coverage of the orderlies and nurses through the window because I had about four different angles of them and all the action through the window. So you can start to dissect that into: you’ve got a beat when the nurse gets a phone call; you’ve got a beat when he finishes a phone call; you’ve got a beat when he turns his back; and you’ve got a beat when both nurses leave. We’ve got four good shots that you could use that are progressing the story.

When I first looked at the scene I thought the only time I really see a spot for the nurses is when Holden gets nervous as Kemper comes closer to him, and Holden looks over his shoulder to the nurses to make sure someones watching. That was the obvious place and that dictated which angle belonged to Holden’s POV. So I thought, “Okay, I’ve got one.” And then Kemper’s Close Up before he lunges from his bed has a pause for him to see the nurses leaving. So there’s two. Then I played it for David with only the two shots in there and he gave me the note, “You want to make sure that Kemper is in control of this, that the timing of the nurses leaving isn’t a fluke”. So that’s why we snuck in another one of him clocking the nurse getting up and moving to the back of the room – just before they leave. Kemper’s paying attention to when he’s going to strike. And then we put one all the way back at very beginning of the scene to show that Kemper is keeping an eye out. That was not obvious to me when I was first doing the scene. I was thinking, What does David want me to do with these nurse shots?

HULLFISH: That’s fascinating advice because it felt like it was obvious that that’s the way it had to be assembled.

BAXTER: That means it was effective but when I was first doing it it wasn’t obvious at all.

HULLFISH: I think I know the answer to this, but what was the point of the final Park City Kansas locator graphic just before the credits?

BAXTER: What’s your take away?

HULLFISH: My take away is: “Can’t wait for next season!”

BAXTER: There you go. That’s the answer.

You’ve picked the ripe plum there. There’s a lot of juice in that story because after everything was shot, David presented me with the idea of showing eight little accounts of the BTK Strangler and gave me the task of sprinkling them in through all of the episodes, saying “If we shot these where would you place them?” So it wasn’t initially written into the original script. I went through looking for locations in every episode where it didn’t confuse the audience. One of the great privileges we have with Fincher’s work is his friendship with Steven Soderbergh and over the last three or four things I’ve cut with David, once we are happy-ish, Stephen gets a QuickTime at David’s request and re-edits the story line, which I adore.

I think that’s Steven’s hobby. If you’ve ever paid attention to Soderbergh’s website, he’ll take Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and turn it black and white and put the soundtrack from The Social Network on it and put it up as a study of blocking and staging. He’s into it! With our work he sometimes drops scenes, others he re-arranges. He’s not shy of hacking into things with a cleaver and it’s just so fascinating to watch and to have your own work represented back to you in a different way. I really look forward to those moments and I watch them intently for things that are helpful.

If Steven’s done ten things, we might use two of them and they’re two great ideas. I highly value it. There probably would have been a time in my life when it made me nervous or exposed me for shit I didn’t think of, but I think we all need to be open to anything that’s constructive and helpful.

It was actually Steven’s idea to take that last scene of the BTK Strangler and place it at the end of the last episode. Both Fincher and I fell in love with it. I loved it for a bunch of reasons. One, because it is the promise of season Two. It also gives more use to the Zeppelin track “In The Light” which I just adore, so you can keep it cranked up at full bore all over that scene, and it had that huge beat where it brought out the location title…that goes back to what we were talking about with the whistle blowing in the music track when we see the rock in the evidence room. When I was able to time music beat to the Park City graphic, I was high-fiving myself I was so excited. “Am I making too much of that title? F**k no!” It’s just awesome coming up on that beat! It feels great.

This is how one idea spawns another idea. It’s the whole tennis game of filmmaking. Because Steven picked that piece up and put it at the end, I then reconsidered where we put all of the other BTK scenes because I liked how isolated that one was at the end. So from that I explored starting all the episodes with BTK.

Do you remember “Six Feet Under?” it always started with the story of the death, then the title sequence and then you’d have the entire episode. It was that formula of saying, “Here’s a completely separate story. We’re going to give it to you as a morsel then we’re going to give you our title sequence and move onto the main course.

HULLFISH: Again, it’s so interesting to hear the back story because with hindsight being 20/20, it seems like that’s always the way it should have been. One of the things that really strikes me as great advice from the many editors I’ve talked to — and you have pointed it out several time in this interview — is that editing is a process that takes shape over time and iterations and you need to make room in your thought process that changes will happen and that they SHOULD happen after the initial cut.

BAXTER: I allow the work to evolve. I don’t hold on tight to it. I don’t work in a system of “This is version 1, this is version 2, this is version 165, let’s go back to version 122.” I just keep moving forward. And if we want to go back to something else I’m happy to build that again from scratch. I’m not a cutter and paster of old things. I’m happy for it to be loose or organic until time runs out and it’s “pens down.”

You get afforded that luxury if you work with clever people. The evolution of what you’re doing should be explored and experimented and broken and fixed. If you’re working with chuckleheads you’re on defense, and then you do need to save and preserve what you’ve done: so you can walk down a pathway to illustrate the fact that it was a pointless exercise and return. But I never feel that way with David.

Each person you’re working with requires a different approach. It’s not just the material but it’s how you’re interacting with the people around you and then it’s all a different chess game depending on the characters involved. The leeway I have with David and how I’ll present scenes is that I can sometimes show stuff very loose at first, because I don’t want to give him something that’s completely defined, because I know as we hit the ball back and forth to each other, it all works out. But there’s other people, if I don’t have it polished, they panic. So there’s other times you’ve got to hold it back until it’s feeling like a finished thing.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now