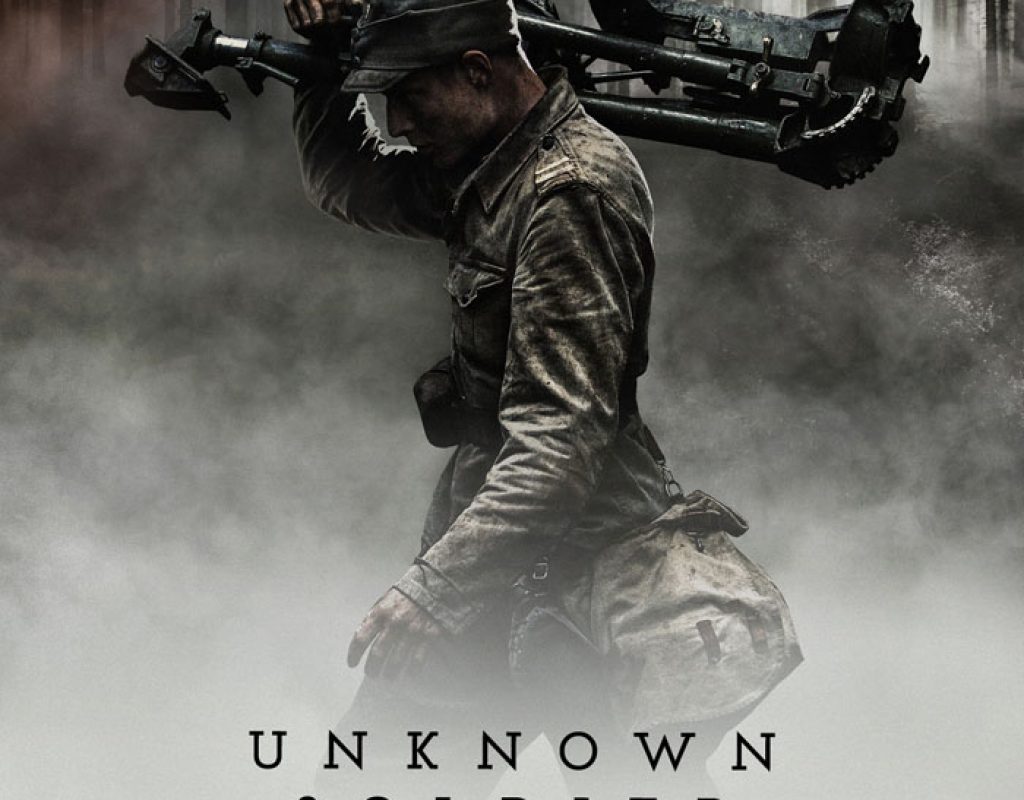

Benjamin Mercer has been a feature film editor for more than a decade, after transitioning from a successful high-profile TV commercial editing career. In addition to cutting TV series, he has cut more than a dozen European (mostly Finnish) features, including the critically acclaimed Unknown Soldier (2018) for which he just won the Finnish version of the Oscar (called the Jussi-awards) for Best Editing. He has been editing on Avid since 1993, but has also edited with FCP7 and was an early adopter of FCP-X when it was released.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: Give me a bit of background on your career.

MERCER: I started film and tv studies in 1993 and ever since, I’ve been working. I worked all through school at the Finnish Broadcasting Corporation (YLE), first in VT then transmission and eventually editing weekly magazine shows.

It was the early 90s and Avid was pushing through. Our school was one of the first in Finland to have an Avid system. So, I was really at the right place at the right time. The tectonic shift from tape-based editing or the film bed to non-linear was just beginning. That opened up a lot of opportunities for me at the YLE to teach seasoned, yet computer-illiterate editors how to operate a non-linear system, and in return, I could sit in with them learning the trade. After film school, I moved to Helsinki to work as broadcast trailer editor for Channel 4 (Nelonen). Little did I know at the time what great training that was into basic narrative structure; speeding through movies looking for essential lines to condense the plot into a 30 second trailer.

After only a year at C4, a friend of mine, Jappe, approached me to work for him. He had become hugely successful as a commercial director, working on international projects. I remember that phone call because I said to him, “My intentions are to become a film editor and going into commercials is the wrong direction.” His reply was superb. “Don’t think of these as commercials. Think of these as short, short, short films with a million buck budget.”. He had me sold. So I joined him in this commercial production company. We mainly produced high end brand commercials. Editing spots is really where I learned the fundamentals of good story telling: elucidate, isolate, illuminate.

It was all about the essentials. We were doing international commercials for Nokia at their zenith, so we had budgets that came laden with responsibility. I got to work in London’s Soho district and to understand the ins and outs of post-production. I was in my late 20s and I was just burnt out. It had become a chore and all of the fun had gone. Working with these clients, when you don’t get your ideas through, you kind of feel stepped on. As a young guy it was hard for me to see things from a clients point of view. So I decided to go freelance. The moment I did, long-form work came my way. Many of the directors I worked with on commercials were feature film directors also, and I was approached by one. Ten years after finishing film school I got my first phone call saying, “I’ve got this film coming up. Would you consider editing it?” I said, “Hell yeah!” And since then I’ve been doing a film a year. I still keep my chops up with commercial work.

HULLFISH: Was all of that edited on Avid? Did you ever do FCP7? And when did you make the switch to FCPX?

MERCER: I’ve been on Avid since 1993. When I left Woodpecker Film to work as a freelancer, that was when I had to buy a system. I tested Premiere. Final Cut Pro seemed to have a clever solution for someone young and needing to buy his own kit. It was an easy choice. Just buy a Mac, a Sony mini-DV player and Final Cut Pro. It was inexpensive and it was more modern than Media Composer. I was the first to cut a cinema released movie using FCP in Finland (Year of the Wolf). At some point, the price of Avid came down, so I bought the Avid Media Composer software, out of interest mainly. But Media Composer wasn’t evolving. Premiere was stepping up their game. Premiere then was really just an interesting alternative version of Final Cut, Then, around 2011 I cut a film for the same director as Unknown Soldier. FCP7 required me to break up the timeline into several projects and that was just a nuisance. I was ready for something new to come along so when FCPX did come along, I was quite happy, even with all its short comings.

MERCER: I’ve been on Avid since 1993. When I left Woodpecker Film to work as a freelancer, that was when I had to buy a system. I tested Premiere. Final Cut Pro seemed to have a clever solution for someone young and needing to buy his own kit. It was an easy choice. Just buy a Mac, a Sony mini-DV player and Final Cut Pro. It was inexpensive and it was more modern than Media Composer. I was the first to cut a cinema released movie using FCP in Finland (Year of the Wolf). At some point, the price of Avid came down, so I bought the Avid Media Composer software, out of interest mainly. But Media Composer wasn’t evolving. Premiere was stepping up their game. Premiere then was really just an interesting alternative version of Final Cut, Then, around 2011 I cut a film for the same director as Unknown Soldier. FCP7 required me to break up the timeline into several projects and that was just a nuisance. I was ready for something new to come along so when FCPX did come along, I was quite happy, even with all its short comings.

I was trying to understand the philosophy behind key words and smart collections. Really understand them: Should the keywords be verbs or should they be adjectives? How should you use a keyword collection?

I understood the mechanics. You select this clip and then you give it a name. It’s kind of like a bin, but it’s not. I could sense a bigger picture, but couldn’t quite see it. And that fascinated me. I was convinced that the guys and girls at Apple were smarter than me and understood something that I didn’t. Of course I had to unlearn my Avid skills and my FCP7 skills. After doing several commercials and short films, I got the mechanics of it, but the deeper learning took some time… trying to really understand the logistical wisdom behind FCPX.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tOPTno2xVqY&t=27s

HULLFISH: I love this idea that you were trying to figure out how to use a keyword and whether it needed to be a verb or an adjective. What did you decide? What’s the big wisdom? Me being a guy that looks at FCPX from the outside and says, “I don’t get it.” So many people love it. What am I missing?

MERCER: In a word, fluidity. My big “aha” moment – my eureka moment – was when I figured that I could always reset my situation by just clicking on this and clicking on that and then I’m back to square one. I can see everything.

I realized that I became nervous with the fluidity within FCPX. So as an FCP7 or Avid editor, you place these clips into that bin, you make some subclips of them maybe and you place them into THIS bin and they are solid and they’re unmovable until you move them. And I realized that with FCPX – and where the hate speech was coming from – was that editors were becoming unsure of themselves or of the application: what the heck just happened to my clips? Where did they go? Did I delete them? Are they here on the system or are they gone? When I realized, “Oh, I just click on this library and make sure that everything is showing, then I’m resetting the situation and I feel I’m on top of the project again rather than being taken for a ride. I am master of the project again.”

In recent years, I’ve learned to snowboard and it’s kind of a good analogy that it’s okay to “lean in”. Just trust the board. The more you lean in the more the board will cut into the snow and stability is found. So I learnt to trust the system. To just go with it even though my event viewer is (visibly) changing all the time. The clip that was just there a moment ago, now that I’ve marked it, it’s just disappeared. Well, where did it go? Well I don’t know but it’s there somewhere. And then slowly I learned to understand that rather than placing clips into these bins, I give them metadata, it goes wherever it goes, But then slowly I learned to understand where it does flow to (or regroup) and then I learned to think “quantum” -style rather than Newtonian: a clip can exist in several places at the same time with different story functions. This clip or this scene or these groups of clips are part of the “attack” in this scene. But also for this character, this is where he breaks down. So they are two different things. As you know as an editor, sometimes you need to show the action and sometimes you need to show the characterization of your characters – like what’s happening or what’s affecting their psyche. So of course it will fall into another category under another keyword. Once I got a basic naming convention sorted out in my brain, I could then let the one clip coexist in many parallel universes and not be fearsome that I’ll lose them and forget where they are or where I put them. Stability. So that was the day that I learned to snowboard with FCPX.

In recent years, I’ve learned to snowboard and it’s kind of a good analogy that it’s okay to “lean in”. Just trust the board. The more you lean in the more the board will cut into the snow and stability is found. So I learnt to trust the system. To just go with it even though my event viewer is (visibly) changing all the time. The clip that was just there a moment ago, now that I’ve marked it, it’s just disappeared. Well, where did it go? Well I don’t know but it’s there somewhere. And then slowly I learned to understand that rather than placing clips into these bins, I give them metadata, it goes wherever it goes, But then slowly I learned to understand where it does flow to (or regroup) and then I learned to think “quantum” -style rather than Newtonian: a clip can exist in several places at the same time with different story functions. This clip or this scene or these groups of clips are part of the “attack” in this scene. But also for this character, this is where he breaks down. So they are two different things. As you know as an editor, sometimes you need to show the action and sometimes you need to show the characterization of your characters – like what’s happening or what’s affecting their psyche. So of course it will fall into another category under another keyword. Once I got a basic naming convention sorted out in my brain, I could then let the one clip coexist in many parallel universes and not be fearsome that I’ll lose them and forget where they are or where I put them. Stability. So that was the day that I learned to snowboard with FCPX.

HULLFISH: I loved that explanation. Most editors are familiar with using Avid and FCP7 by naming the clips in very typical ways that have been used throughout the history of film and placing them in bins by scene and according to camera set-up. Are you actually doing it differently? Are you thinking in a different way because of the keywords?

MERCER: I’m sure I am. A concrete difference and one that I do miss — I miss from Avid and I miss from FCP7 is the visual approach to arranging a bin visually: Taking these four clips and pulling them aside ever so gently. If I had takes in FCP7 or Media Composer – let’s say I had ten takes. They’d all be in thumbnail view in a neat line and I’d go through the material and think to myself, “That was a really good take.” So I’d lift it up visually, lift it up just a couple of millimeters. And if there was a take that was bad, I’d lower that a couple of millimeters so there’d be this snaking row of takes. So I’d given myself some visual cues.

MERCER: I’m sure I am. A concrete difference and one that I do miss — I miss from Avid and I miss from FCP7 is the visual approach to arranging a bin visually: Taking these four clips and pulling them aside ever so gently. If I had takes in FCP7 or Media Composer – let’s say I had ten takes. They’d all be in thumbnail view in a neat line and I’d go through the material and think to myself, “That was a really good take.” So I’d lift it up visually, lift it up just a couple of millimeters. And if there was a take that was bad, I’d lower that a couple of millimeters so there’d be this snaking row of takes. So I’d given myself some visual cues.

How I think differently now with FCPX is that I think it’s the same thinking but it’s more diverse. So rather than just have the visual cue of up and down – you know, good or bad – beyond having an OVERALL value, there are also MOMENTARY values. So instead of just one long good or bad clip, there’s a clip with many different attributes to them across time. So it’s just more diverse.

HULLFISH: So how are you dealing with that in FCPX? What is giving you those cues and indication that you’ve got the right moment?

MERCER: I still have the visuals. It’s just that it’s a different kind of visual. Now it’s with the red lines, the green lines in the event viewer. Rather than on the timeline.

HULLFISH: What are the red lines and green you are talking about doing for you? Is that something you’re marking?

MERCER: Yes. My selects. How familiar are you with FCPX?

HULLFISH: I bought FCPX the first day it was available, but I haven’t used it that much. I read a few training books. I did an interview with Jan Kovac, who cut Whiskey Tango Foxtrot on it. That’s about it.

MERCER: In FCPX, favorites – which are green lines – and then the red lines, which are rejected moments. So whilst screening the clips, I’d see, for example, that clearly during the first 10 seconds or 30 seconds of this clip, nothing is happening. The camera is basically facing the floor the actors are not in character. There is zero value. This moment would not even have any value in an art house flick. So I reject it—in, out, reject. A red line signifies the area marked. If I have “hide rejected” -activated then the marked area will vanish from view. Wash, rinse, repeat. If I don’t know what I like, then maybe I know what I don’t. Selection—highlighting and rejecting—is central to editing. Sifting an abundance of footage to bring it down (eventually) to only essentials in the timeline.

Many times, when I’m starting off on a project – it’s like I’ve forgotten how to edit. I’m always back in kindergarten. How do I know if this is good? This moment? “Is that a good performance or not?” I don’t know if that’s good for this character until I’m way further down the line editing.

HULLFISH: You need the context.

MERCER: Yes. So, before I have the context, all I’ve got is my intuition: Do I like that? Does it seem good? A considerable chunk of the editing is done in the event viewer in FCPX. In Avid or FCP7, you’d more lightly do a string-out, right?

HULLFISH: Sure.

MERCER: Especially in a documentary.

HULLFISH: KEM roll, selects reel, stringout.

MERCER: A selects reel is basically like ‘favorites’, in FCPX. So when I get around to actually editing a scene on the timeline, I’ll check my favourite selects first. What did I actually like? So instead of going through an hour of material especially in the case of the Unknown Soldier there was a lot of material. Now I can look at five or ten minutes and now I can see that I liked these, but now that I’m further on down the line I can see that that choice – even though it’s a good take or a good moment – actually doesn’t support the character or doesn’t support the turning point in this scene and what I previously hadn’t marked is actually better. As you know, you go through your material many times and change your mind as you go along. So I just find that rather than doing a select reel or a string out that the FCPX method of selecting and deselecting in the event browser is just more economical. And it keeps it updated all the time.

MERCER: A selects reel is basically like ‘favorites’, in FCPX. So when I get around to actually editing a scene on the timeline, I’ll check my favourite selects first. What did I actually like? So instead of going through an hour of material especially in the case of the Unknown Soldier there was a lot of material. Now I can look at five or ten minutes and now I can see that I liked these, but now that I’m further on down the line I can see that that choice – even though it’s a good take or a good moment – actually doesn’t support the character or doesn’t support the turning point in this scene and what I previously hadn’t marked is actually better. As you know, you go through your material many times and change your mind as you go along. So I just find that rather than doing a select reel or a string out that the FCPX method of selecting and deselecting in the event browser is just more economical. And it keeps it updated all the time.

HULLFISH: Between you and Jan, I’m more and more interested in exploring FCPX. Let’s talk a little bit about Unknown Soldier.

MERCER: The first version of this film – based on a best selling novel of the same name – was made in the 50s. And that film is part of the Finnish canon. In the 80s there was a remake with a totally different style. That generated a lot of heat because this was like the holy cow of Finland. So Aku wanted to make it more approachable for this generation of viewers.

I actually edited three versions. We’ve got the Finnish master cinema version then we’ve got the the international cut and the TV-series. The International cut is 45 minutes shorter whilst the series has 90 minutes longer (extra characters, sub plots)

HULLFISH: A lot of the decisions we make as editors are those subtle looks between people or these little things that you have to really be watching the screen and if you’re looking at subtitles you miss all that stuff.

MERCER: Yeah. It’s the nuances that you all miss and I think the devil is in the detail or heaven is in the detail. What differentiates editors from each other is the ability how you can play around with the nuances and that they are legible, but that they’re not underscored, but that you can feed them subconsciously to the viewer without feeling that they’re being force fed. So when you factor in subtitles, all of the work you put into it get a little twinkle in the characters eye to be visible and to be at the right moment – It’s all gone to hell because there’s these big damn subtitles.

HULLFISH: Talk to me a little bit about your approach to a scene. You mentioned that you kind of don’t know how to edit for the first couple of weeks because you don’t know the context. As you’re editing during dailies how does it change once you have the context of seeing the whole movie put together?

MERCER: You need an ability to continue on with work that’s half-finished. So I will keep the scene pretty much open for a long time. I’m not going to try to cut it down. I might have images hanging around in a scene that I know I don’t look like, but for the time being that image or that angle does what I want it to do, but I’m never going to leave it in. I going to have it hang around there until I figure out how to get in that beat without using that angle.

This can drive some directors mad. “Can you just tidy up that scene?” Sure I can tidy it up, but even though the scene could be ugly, and I know it’s ugly, but I prefer that because it’s reminding me of the things that are important. Or things that I like or think are important at the time.

This can drive some directors mad. “Can you just tidy up that scene?” Sure I can tidy it up, but even though the scene could be ugly, and I know it’s ugly, but I prefer that because it’s reminding me of the things that are important. Or things that I like or think are important at the time.

So going back to the original question, I approach a scene more like a sculpture in that it’s just that big rock and I’m chipping away, trying to find the form of the scene and this is where many many film students or people off the street don’t understand why it takes so long to edit. The “je ne sais quoi”, the something special, the “I don’t know what”, the originality comes out of of discovery. The magic in film is something that’s unexpected. It seldom has been created on location fully visible in front of the camera. That took a long time to understand. I would always think editing is so difficult because the writer doesn’t know how to write and the director doesn’t know how to direct and this actor doesn’t know how to act. But then as you grow older you realize that, “no no, everybody has giving their best shot, it’s just that the magic of the screen is something more.” You can’t just conjure it just like that. You have to beckon it out and basically to beckon that magic you have to kind of dance around. You have to be really delicate with it. And then as you chip away at that big rock, the form will begin to show. At some stage the film will then dictate to you and the roles will change.

So the first half is trying to beckon out that form, that living being from within the material. When you could breathe life into it, then the film itself will dictate to you as an editor: “Right, now go back to the material and search for the clip where the girl lifts her eyebrows. That’s what you want. That’s the right beat right now. Go get it. You know where it is.” So that’s my approach. It’s very elastic. For me “killing my darlings” is a joy. I like the idea of destroying work that doesn’t serve the greater purpose. It means I’ve discovered the purpose in the first place.

HULLFISH: Your experience as an editor of getting to that point where killing your darlings is something that you like is the opposite of what you were talking about back when you you were a young TVC editor saying, “What do you mean? It’s perfect!”

MERCER: Yeah. That’s the naivete in the youth. The good thing in this profession — looking at people like Kahn and Murch — is that it seems that editors get better as they age.

HULLFISH: It would be a good piece of advice for a young editor that you just kind of shouldn’t worry too much about starting that scene. So many people get paralyzed by the idea of, “What’s that perfect first shot?” And you don’t have to worry about that because it will be elastic and it will change with context and it will change as you start to understand the scene more. It’s a process… it’s a marathon, not a sprint.

HULLFISH: It would be a good piece of advice for a young editor that you just kind of shouldn’t worry too much about starting that scene. So many people get paralyzed by the idea of, “What’s that perfect first shot?” And you don’t have to worry about that because it will be elastic and it will change with context and it will change as you start to understand the scene more. It’s a process… it’s a marathon, not a sprint.

MERCER: Yes. That’s something that I learned working in commercials. That I just needed to build the assembly. For me an assembly is the elementary tool for the editor. I never show assemblies to the director. One two three—one two three and f**k it if it’s out of tempo and rhythm. Of course it will be. But you’re willing to accept it.

You’re trying to avoid the carte blanche moment. And the best way to avoid it is to just throw down those clips. And also when I start a film, very seldom do I start from the beginning. It’s way too hard. Why trouble yourself with starting from the start? I usually begin with any scene that I find interesting. You break the ice with something you can relate to intrinsically.

Young editors that try to edit from A to Z. The word “process” is really important to understand. Crawl rise walk run fly.

HULLFISH: The idea of editing as a process is a big point for me as an editor. It is one of the things that I feel like I’ve learned in doing these interviews. In my inexperience in doing films at the beginning, I would try so hard to convince the director, “Look, this has to change and this line has to be jettisoned!” I would try SO hard at the beginning, and what I needed to realize was that if I was just patient and give it a month, the director will discover that on his own.

MERCER: Yes exactly. The key word there was patience. To dare to be patient — to sweat it out – because the answer always shows up at the eleventh moment. It’s going to come. It’s just how long can you sweat it out and dare to wait for it to come.

HULLFISH: That’s a hard lesson.

MERCER: It’s a hard lesson. It’s hard to do when you got producers and directors breathing down your back saying, “So what does it look like? How does it look today?” As an editor, it can make you feel guilty, like you may have been working your ass off but you have little to show for it.

MERCER: It’s a hard lesson. It’s hard to do when you got producers and directors breathing down your back saying, “So what does it look like? How does it look today?” As an editor, it can make you feel guilty, like you may have been working your ass off but you have little to show for it.

HULLFISH: Some of that is setting aside ego. You have to be confident to say, “I don’t know the answer right now. But I will get the answer.”

MERCER: Exactly so! And that also comes with experience and the braveness to say “I don’t know.”

When you’re a kid you want to be good. You don’t want to show that you’re weak, but as you grow older you figure it’s okay to be confused—momentarily, I may add.

HULLFISH: I was shocked in an interview with Michael Kahn about Close Encounters where he told Steven Spielberg, “I have absolutely no idea what to do. You just tell me.” That’s a brave thing to tell someone.

MERCER: On the Unknown Soldier, some of the action sequences are very complicated. We had military experts advising us on the tactical matters. Basic storytelling; rhythm, pace, characterisation, advancing the thematics and plot, to all be in line with actual battle tactics. I had a couple of scenes that were really complicated and I went to Aku and told him I didn’t get them and he said, “Don’t worry, you’re not stupid. It’s just a very complicated scene. I’ll walk you through it.” An hour or so later I would say, “I get it! Now you can go away and leave me to work.”

HULLFISH: When you’re making those revisions like we were talking about: you’ve chipped away, creating this scene and you’re trying to revise it. What are those tools? How are you working inside of FCPX to be able to do that? Are you looking at what you were saying was like a selects reel and then just doing the typical trimming in the timeline?

MERCER: I’ll version just like any other editor. But in FCPX I’ll version by method of compound clipping and smart collections.

MERCER: I’ll version just like any other editor. But in FCPX I’ll version by method of compound clipping and smart collections.

It’s exactly the same thing that all editors do on any platform. It’s just very quick in FCPX. Versioning gives me peace of mind. It’s like the ultimate undo button. I seldom revert, if ever. Sure we can go back to a previous scene version but then I will reedit that version to fit into the new slot. There is simply no going back.

HULLFISH: That makes total sense to me. Say you and I go out for a beer together as editing pals and you tell me, “You need to change your ways. Leave Avid. Come over to the FCPX side. Step away from the 1990s. The water is fine.” What would you say to convince me?

MERCER: In this situation we would have had several beers, because I wouldn’t do that to any colleague of mine because I understand that there is a symbiosis between a man (woman) and his (her) tool.

So if you and I had had maybe ten beers, I would recall an analogy from way back: Avid Media Composer is like the Cadillac. It’s got class. It’s smooth. You can go from East Coast to West Coast, no sweat. The old Final Cut is kind of like a Toyota Corolla. It’s got great fuel efficiency, it’s got all of the gadgets. It will get you from East Coast to West Coast, not in the same style but it’s got great air-conditioning.

I would then buy us another round and continue in a drunken slur: “the reason you want to go from Medi Composter to Funal Cat Xx is, is, is, it’s like going from a gas guzzler to a Tesla. This is a car that has a button that says “Ludicrous Mode—Ludicrous for god’s sake!! It still has f-f-ffour wheels, but it’s ludicrous!

But seriously. Changing the tool will also affect the way that you approach the edit and when you change the way you approach the edit, you shake off old rust and cobwebs. You have to rethink your own approach to editing, not just the mechanical side, but also the psychological approach.

HULLFISH: So what do you miss about Media Composer when you’re on FCPX and what do you miss about FCPX if you ever go back to Media Composer?

MERCER: About Media Composer, I miss you could freely arrange the clips in the bins. I liked that.

HULLFISH: What about the other way around?

MERCER: There is no other way around.

MERCER: There is no other way around.

HULLFISH: The issue of lag in long timelines is something across many NLEs.

MERCER: Yes. And after about an hour long timeline, on FCPX too. Though there are work-arounds so it’s no real problem. It’s worth a word to mention how super reliable FCPX was on this gigantic project. To be honest, it would probably crash once every two weeks. I learned to see the signs. But I never lost a single cut. Restarting would return me exactly where I was. Never got corrupted and it was a huge project and it’s awesome considering that in 2011 I paid 300 bucks for the software and I haven’t paid 1 euro more since (with exception to third party apps). Compare that with Avid’s pricing model or Adobe’s pricing model.

HULLFISH: And Resolve’s the same way. I bought a Resolve dongle five years ago and it hasn’t cost a penny since then and I’ve upgraded from 9 to 14 at this point.

MERCER: It’s very interesting to see what happens with Resolve. I think I’d like to give that a test spin again, just to see how it would work on a short project.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now