Seven years ago we heralded in a new version of Apple’s venerable video editing app, FCPX. As a leader in the FCP community and an enthusiastic Final Cut Pro user, I had advocated for Final Cut as one of the founding leaders of the FCP User Group network, which was one of the 4 original communities with Michael Horton’s, LAFCPUG, Dan and Don Berube’s BosFCPUG, and SFCutters founded by Kevin Monahan and Claudia Crask.

Seven years ago we heralded in a new version of Apple’s venerable video editing app, FCPX. As a leader in the FCP community and an enthusiastic Final Cut Pro user, I had advocated for Final Cut as one of the founding leaders of the FCP User Group network, which was one of the 4 original communities with Michael Horton’s, LAFCPUG, Dan and Don Berube’s BosFCPUG, and SFCutters founded by Kevin Monahan and Claudia Crask.

Changing an entire generation of editors, Final Cut had already broken Avid©’s stranglehold on broadcast editing and in a few short years, pushed the likes of Edit, Edius, Media100, Pinnacle, and TruVision out of the marketplace. When Apple rolled out the ProRes codec at NAB in 2007, it was an announcement that landed on rather deaf ears of the FCP community that was in the midst of fighting amongst on the battlefield myriad of codecs and compressions schema’s being used.

In 2007, we struggled through a radically changing post production process, hampered by the myth of ”realtime” Long GOP HDV formats or forced into using the lossy, overly compressed Mpeg based formats found in editorial. This was a time when the majority of the high end content was being handled as film and transferred via HDCamSR Tape. While the transmission stream codecs were great for direct to broadcast, for the advancing state of post production, something more was needed to maintain the quality being captured by Sony F900’s, Thompson’s Viper, and Arri’s D20.

I say needed, because Quicktime was lagging in the market and still fighting a cross platform gamma issue as the video marketplace bursted at the seams. Apple introduced multiple flavors of ProRes, a mezzanine codec to be used as a replacement for the Apple Intermediate codec, a low performing, lower quality option Apple used trying to bypass some of the limits and issues for HDV playback on the Mac platform.

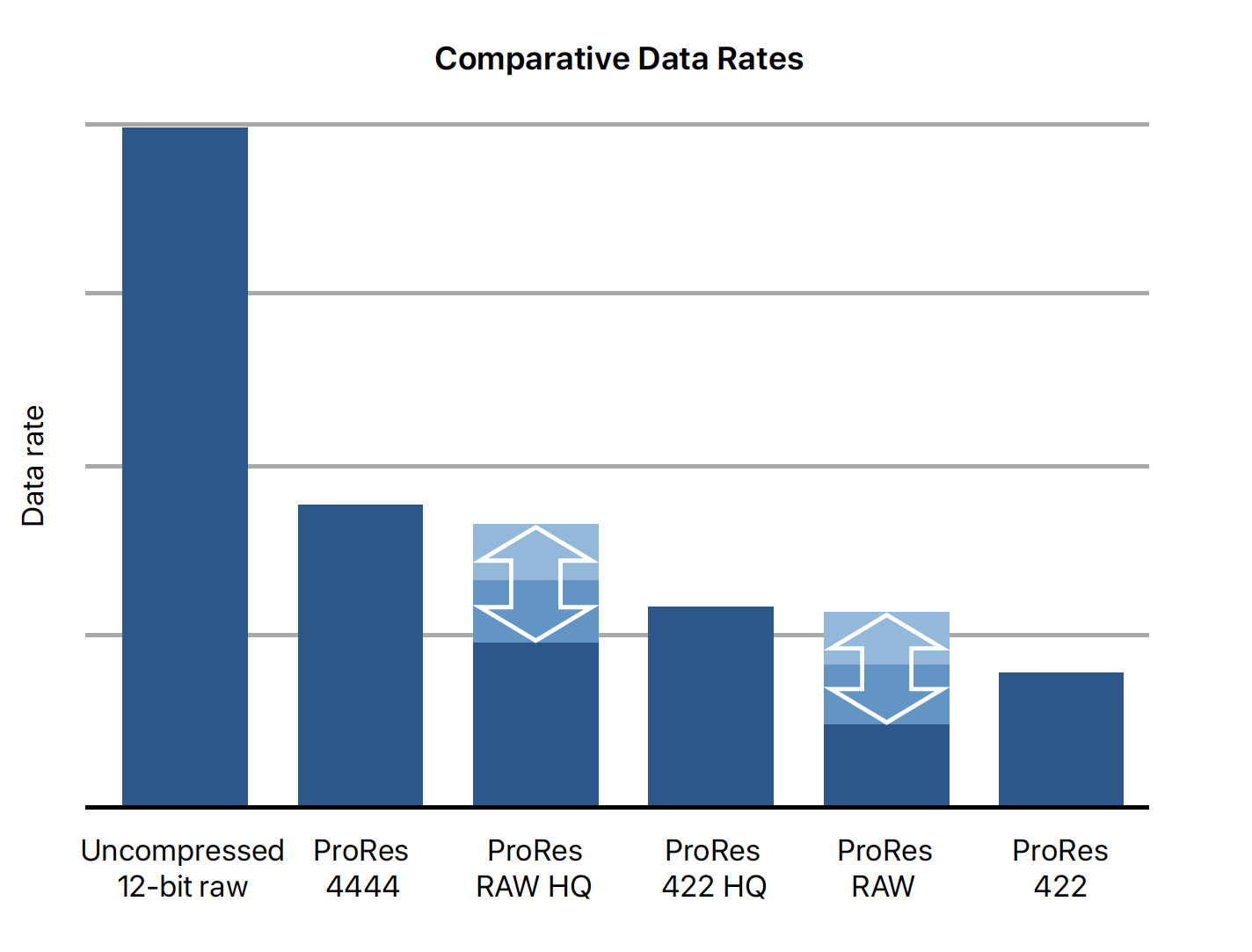

ProRes was not initially embraced as widely as expected, as transcoding between formats took precious time and even more valuable disk space. It was happening just as FireWire editing had reached its limit and the first generation of Thunderbolt devices were still years away. Yet ProRes was just getting started, as a variable bit rate, DCT compressed format, whose most complex high bit depth variant was easy to decode, saving the CPU’s of the time when GPU processing was just starting. That saved users from handling the computational complex decode LGOP based codecs and playback requirements.

Everything Changes

Everything Changes

Then in 2010, Arri’s Alexa camera launched as the first camera to implement ProRes as it’s main internal recording format. Arri’s support for ProRes blasted the codec to the forefront of the industry, pretty much forcing the remaining NLE manufacturers, including Avid, into supporting the codec. By 2011, Apple had added a 4444 version to ProRes, a 12bit visually lossless variant with added alpha channel support to allow projects to be handed off properly for composting.

However, the launch of FCPX was something else, radically departing from anything resembling any existing non-linear editors. Initially, it was received in a somewhat less positive way than what Apple had expected. In fact, most of the reviews, including my own for Macworld magazine and another online review for Creative Cow published on launch day, laid bare many of the missteps.

With the new UI design and a “magnetic timeline”, users were either elated or horrified, with very few reactions in-between. I was not very popular in Cupertino for my vocal stance that FCPX “was not made for professionals” and I took serious issues with the lack of support for nearly everything used in and for professional level post production or broadcast. FCPX had arrived lacking the most basic functionality, without any way to generate bars and tone for calibration. It also had an inability to use any external hardware to monitor the image or to exchange data with other applications. On top of all that, it functionally lacked the ability to import or export an XML, EDL or other industry interchange formats, leaving users alone, forced to enjoy Apple’s editing folly.

The backlash was deafening. Adobe dusted Premiere off and pushed it back out, even bringing it back to the Mac platform. Three short years later it had taken the NLE lead back from Apple, all while many FCP7 users just kept chugging away with legacy software on their aging systems because they could. Many users embraced a Wintel / PC lifestyle and found that it wasn’t all that bad.

Jump to 2018, and things have changed in a big way. Apple’s iOS dominates in the mobile space, Adobe’s Premiere is still chugging away even though it barely leads the marketplace (it still runs better on Windows IMHO), while Avid still dominates in the markets doing script based episodic television and features. In the midst of all that, Youtube, Netflix and Amazon are re-defining production requirements and post deliverables

ProRes Raw

Scott Simmons asked me to go back and take an honest look ProRes Raw, and in doing so realized that I would need to discuss FCPX’s changes since ProRes Raw is currently only available in that application.

asked me to go back and take an honest look ProRes Raw, and in doing so realized that I would need to discuss FCPX’s changes since ProRes Raw is currently only available in that application.

ProRes Raw is an effort between Apple and Atomos that allows the Atomos Sumo, Shogun and Inferno recorders to ingest a camera manufacturers raw data stream. It then imparts the specific properties of that camera centric data into a newly created version of the ProRes container. This leverages the ease of playback while maintaining the bit depth, colorspace, LUT parameters and capabilities of the camera’s native codec within an HDR compliant, 12bit linearly encoded asset that gives you a file size at or less than the camera original.

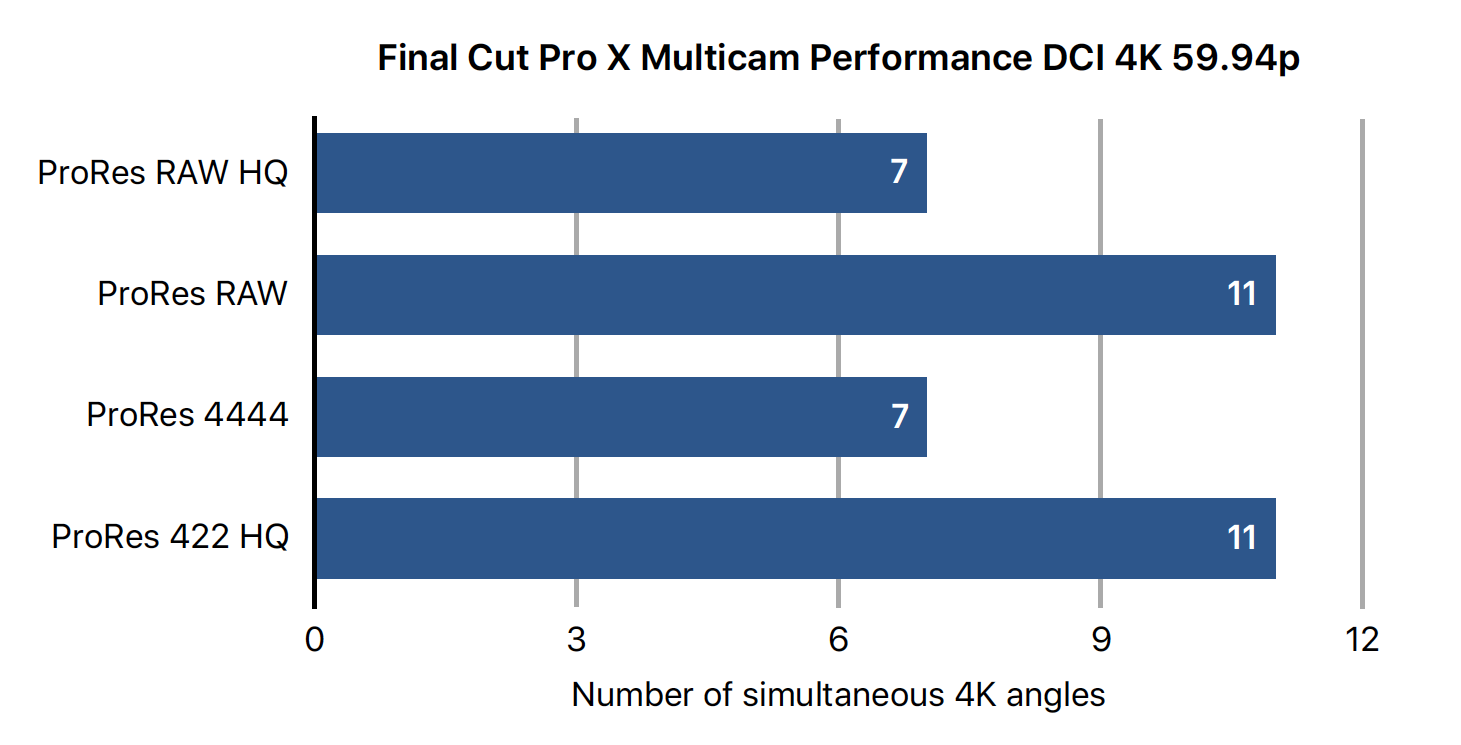

This happens by passing the CMOS sensor data directly to the recorder, rather than the current process, where the camera is internally debayering / demosaicing the file and then recording the image. The unique part is now the Atomos ProRes Raw workflow offloads that processor numbing debayer process to a later stage in production, where additional CPU’s and more powerful GPU processing is readily available. Delaying the actual image processing until it reaches a computer system means dramatically reduced power consumption and correspondingly increased performance in the camera and recorder combination, further enhanced by the overall lower bandwidth and storage requirements of the ProRes Raw container. The plain version of the Raw codec requires about the same overhead and playback needs as ProRes 422HQ encoded file at the same frame rate and raster size, while the higher quality Raw HQ version is not any more difficult to handle than a ProRes 4444 version. C

Because that captured data is commonly found in some version of a log encoded file, FCPX has the ability to apply a log conversion on those linearly acquired files during import, allowing your PrR files to be handled in an identical manner to the camera originals, even though FCPX decodes ProRes Raw into linear HDR values.

Final Cut Pro X

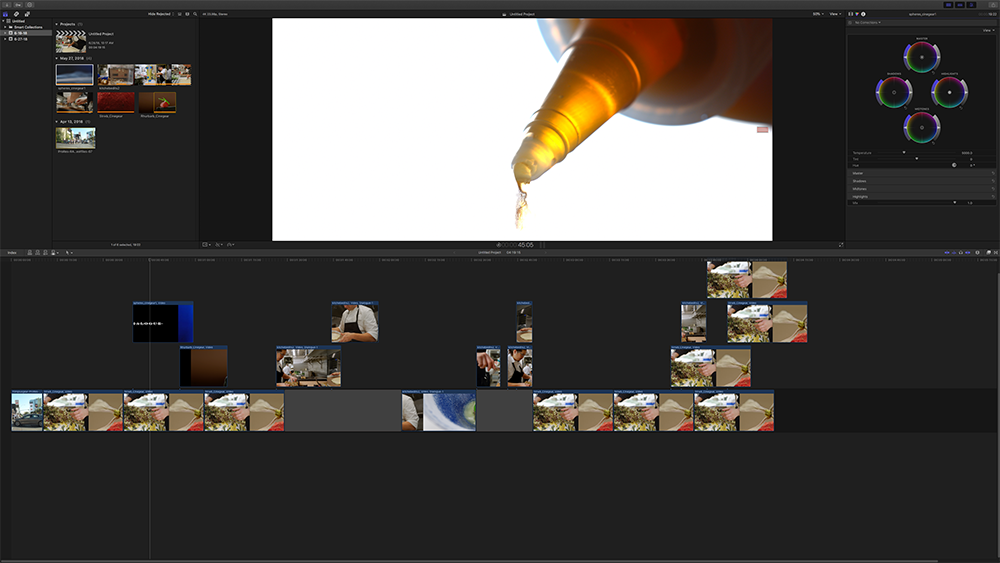

Since it’s rocky release, FCPX has been updated over 30 times. It has gone from an obstinate child into an application that has continually expanded in use and functionality. While I still have minor issue with how the magnetic timeline and some of the organizational items work, I have gotten used to working in it, especially since many of my original negative issues were updated early on.

No NLE has been able to avoid the constant processor limiting tweaks taking place behind the interface. Whether it’s processing proxies or optimizing media, or just confirming you are on the Internet, these background task loads will drag your computer back to the stone age. Thankfully, Final Cut Pro X lists these eight background tasks for you so that you have an idea of what is happening when you can’t seem get your computer to respond.

Overall FCPX has evolved nicely, albeit around a ProRes workflow. Many of the current cameras on the market are not native to Apple’s NLE. While RED’s R3D format is handled efficiently, Sony’s XOCN codec has number of issues, with the 6K versions from the newly released Venice camera completely incompatible. The same goes for the native files from the latest Vision Research Phantom cameras and ARRIRAW outputs from the Alexa LF and Alexa 65. Granted, not a lot of FCPX users are on those cameras, but it highlights that Apple’s promise to maintain an open application supporting camera native codecs has changed somewhat.

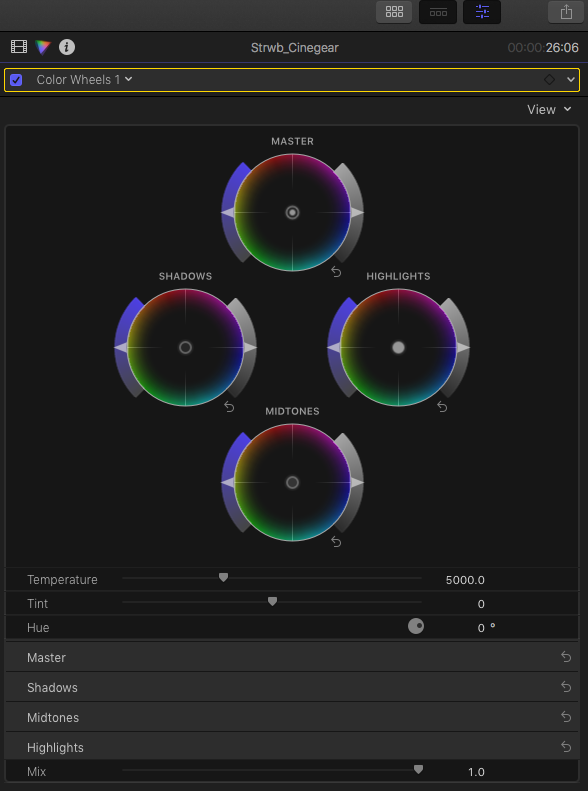

Two things to note in the latest release of FCPX are changes that reflect the evolution of the post process. We now have an enhanced Color Board, with options to see Color Wheels, Color Curves and now even Hue vs Sat vs Luma adjustments. You can open even wider with the inclusion of Wide Gamut Color and the output of HDR compatible metadata in the I/O. While not everyone understands closed vs open captioning, everyone can appreciate the commitment Apple is showing with the ability to open, save and even edit Closed Captioning content. Using the Roles functionality, users have the power to link CC content to individual clips in the timeline, allowing for a re-ordering of media while maintaining the relative captioning content in place with the clip, much like we currently handle dual system sound.

What’s Next?

What’s Next?

Apple’s ProRes codec helped change a generation of production and post users. From its addition to FCP in 2007, the ProRes codec has taken the complexity out of production and post, making it easier for pros and beginners alike to achieve the highest quality deliverables while maintaining a greater level control of the process and the image. With ProRes Raw, you can see the push to bring ProRes back into the picture for an entirely new generation of filmmakers, in a way they are far more accustomed to. By limiting the ProRes Raw workflow within FCPX, Apple can work out issues with this new workflow in a closed ecosystem, while also limiting when other manufacturers may get to try out ProRes Raw.

Apple’s ProRes codec helped change a generation of production and post users. From its addition to FCP in 2007, the ProRes codec has taken the complexity out of production and post, making it easier for pros and beginners alike to achieve the highest quality deliverables while maintaining a greater level control of the process and the image. With ProRes Raw, you can see the push to bring ProRes back into the picture for an entirely new generation of filmmakers, in a way they are far more accustomed to. By limiting the ProRes Raw workflow within FCPX, Apple can work out issues with this new workflow in a closed ecosystem, while also limiting when other manufacturers may get to try out ProRes Raw.

From everything I’ve seen, ProRes Raw appears to be a worthy successor to the existing codec. Being able to capture, control and manipulate the native aspects being output from any camera only increases a filmmakers capabilities. I expect that ProRes Raw will be the native codec for at least one camera manufacturer within a year or so, and that will hopefully open up a wider market for other companies and products.

As for Final Cut Pro X, the jury remains out. There are a large number of editors that enjoy working with FCPX and more will learn as Apple pushes back against NLEs like Adobe Premiere and BlackMagicDesign’s DaVinci Resolve. Something Avid learned the hard way is that it’s really, really hard to climb your way back up the mountain once you’ve been knocked off, no matter how powerful your toolset. FCPX left a bad taste in many editor’s mouths, so it’s going to take more than ProRes Raw to bring people back en-masse.

If only Apple’s hardware commitment to the professional market was compelling enough for people to want to switch.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now