Jonathan Schwartz has been editing for the last decade, including as assistant editor on It’s Complicated, and as the editor on Allegiance, Let’s Be Cops and Mike and Dave Need Wedding Dates. He also edited two seasons of the hit comedy, Modern Family.

Art of the Cut is brought to you by our friends at Frame.io.Video collaboration for the 21st century Read all of the AOTC interviews or learn more about Frame.io |

Art of the Cut talked to Schwartz about his work on The Spy Who Dumped Me and the secrets to cutting comedy.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: Is it possible for an editor to get typecast?

SCHWARTZ: You’re starting with a heavy question! It’s absolutely possible for an editor to be typecast. I think it happens frequently and easily and understandably. Imagine being the person on the other side of the hiring: the producer or the director. It’s comforting to hire someone who has already done a successful thing that is similar to the thing that you’re about to undertake.

To me, the question isn’t, “Do editors get typecast?” The question is, “Is it fair that editors get typecast or that anyone gets typecast?” I’ve come to the conclusion that some people do one thing really well and some people do many things really well and it’s hard to tell who falls into what category until they’re given the opportunity to succeed or fail in something that they haven’t done before. You see it most demonstrably with actors and directors. An actor who can do a lot of things well, in my opinion, is Robin Williams, who was an incredible comedic actor and also an incredible dramatic actor.

HULLFISH: Tom Hanks started doing comedy and proved he could do drama.

SCHWARTZ: Exactly! Similarly, there are editors who cross boundaries. My first boss and my mentor is Paul Hirsch, who, if you go through his list of credits, it’s like every genre of filmmaking: Star Wars, Carrie, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.

HULLFISH: What is the difference that you see between the TV editing that you’ve done and the film editing that you’ve done?

SCHWARTZ: That’s a great question. That’s a big question.

HULLFISH: What’s the difference in your daily workflow? Do you approach it the same way? Or because you have shorter time frames on an episode of Modern Family than a feature film — that you know you’ve got to do a certain thing in your first cut because you’re not going to get another chance?

SCHWARTZ: I was a feature assistant before I became a television editor, so I was never an assistant in television. When I started in television, I just did what I had seen my bosses do in features. That got me into a lot of trouble. I ended up working a lot of hours because — you’re right — television has a much faster schedule than features, and so you’re expected to put together more minutes of content in a shorter period of time. After editing a few episodes on a series, you know what your producers like and you start cutting for that because you can anticipate how a scene is going to ultimately end up. You can just go in that direction right away. Whereas in features, you might cut a version that you like more in addition to the version that it seems the director wants based on how she shot it. There may only be slight differences, but you can take the time to explore the footage and really get into it and explore all the options because the timeline is long enough that the final due date isn’t for months. You fool yourself into thinking you have all the time in the world.

Certainly, in television, you move through material more quickly. You get footage and a month later you’re onto the next episode. The overall process of the piece of work is so much quicker in television than in features that in television you do a lot of deciding that what you put together is close enough to the target, and you move on. Whereas in features you really have a length of time to marinate over a scene or the entirety of the piece to make sure that you’re getting the most out of the footage and that you’re really in the best possible place with it. That is the speed and the pace and the mode that I prefer. I really like it when a scene is cut and it feels good, but then you realize that to help the story as a whole, you need to bring out a certain aspect of a character in that scene. So then you go through the footage all over again, and you’re still cutting the same scene — it’s going to be the same dialogue — but now we have to make sure to bring out such-and-such a character trait of one of the characters. So you find the pieces, the little human moments that you need to sneak in to do that. I think you do more of that in features than you do in television because you have the time to.

HULLFISH: The key to good editing is revising and you have more time to let it be a process when you’re on a feature.

SCHWARTZ: Yeah. What’s interesting is that production schedules for features and television are both very tight, so when you’re doing the first pass on either, you’re really rushing through. But in television, when you’re done shooting, you get three or four weeks to finish the episode. In features, when you’re done shooting, you have six months, eight months, and so it just affords more opportunity to further revise.

HULLFISH: What is your approach when you’re sitting and looking at a blank timeline? Do you just dive into each individual shot or do you put them together like a KEM roll and watch them through?

HULLFISH: What is your approach when you’re sitting and looking at a blank timeline? Do you just dive into each individual shot or do you put them together like a KEM roll and watch them through?

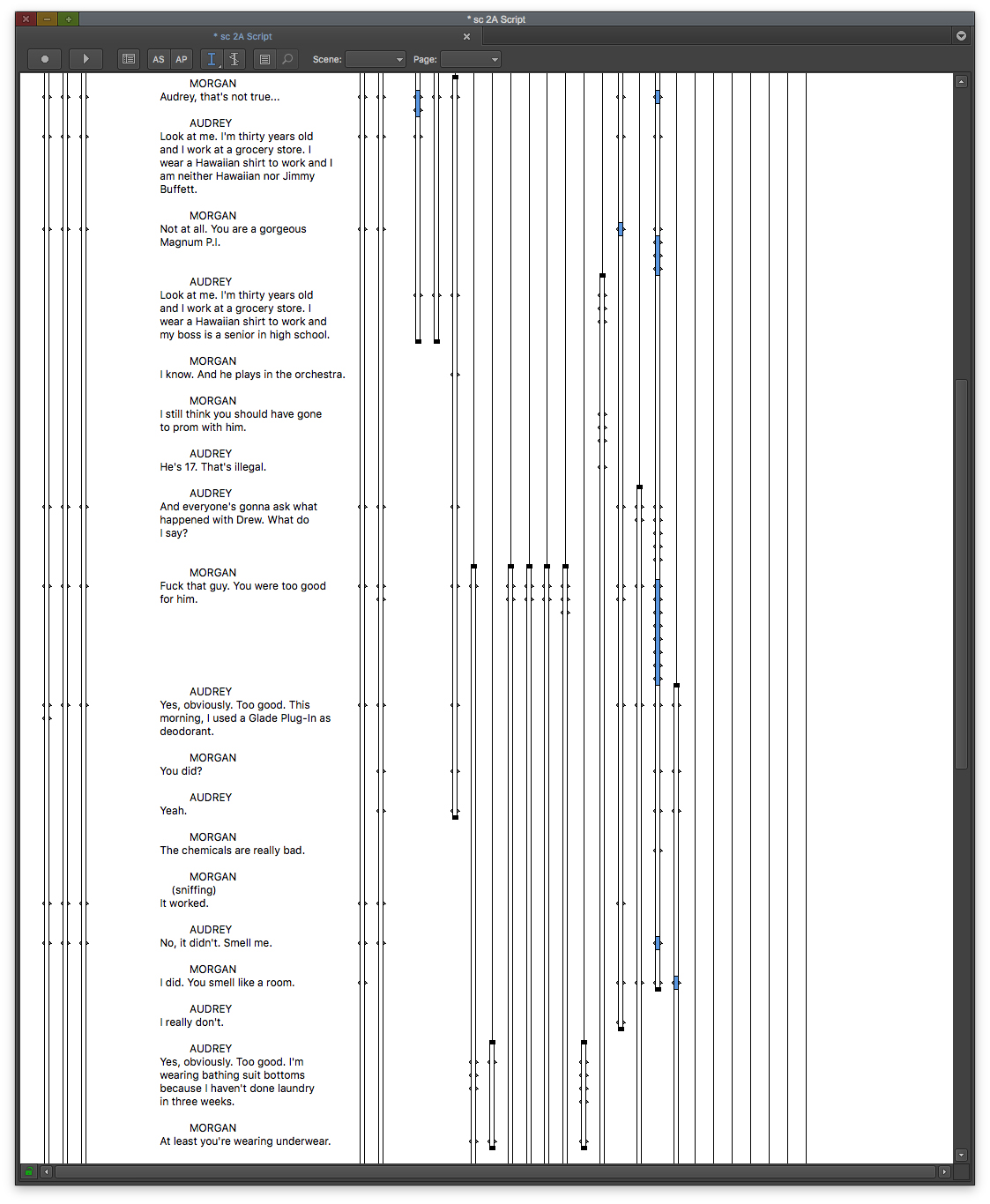

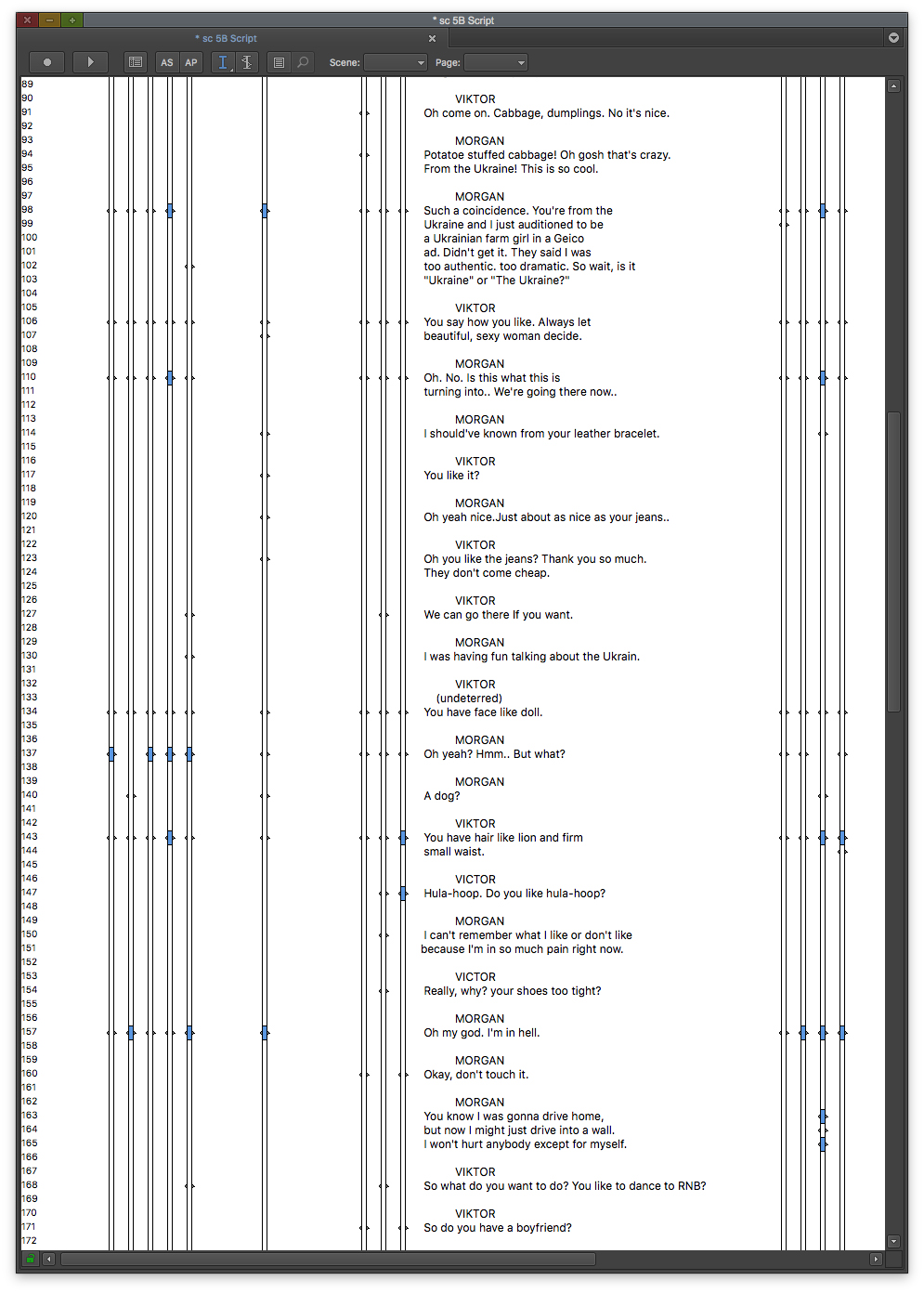

SCHWARTZ: I have a two-forked approach. One is getting the footage extremely well organized and actually that task goes to my assistant editors. I use the “scriptor” tool in Avid (formally called Script Integration or ScriptSync, with phonetic assistance) and I have my assistants make scripts. Because I work in comedy and deal with a lot of ad lib, my assistants will add the ad lib to the scripts — to a degree. You don’t want a script that’s pages upon pages upon pages. At the same time, if there’s an ad lib beat that gets played around with a bunch, you want that represented in the script so that you can find it again. The way we deal with less repeated ad libs is by using a different color for the nodes on the script, so it’s kind of an art to determine what ad lib deserves to be written into the script in full and what ad lib is just a differently colored node on an existing scripted line. My assistant editors — Blair Miller is my first assistant and Lauren Brown is my second assistant — God bless them for having the patience to explore the optimal scripting method on each film. And the benefit of having each scene scripted this way is so that you can easily get back to any line. While my assistants are doing that, I’ll read the scene in the lined script to remind me what the scene is, what’s happening, what happened previously and what happens in the next scene, and then I just start watching the set-ups from the first set-up through to the last.

While I’m watching the footage, I drop locaters for stuff I like. I started doing this on Modern Family, and there were certain things that I was specifically looking for in Modern Family dailies because it was a mockumentary: nonverbal reactions, which served as valuable cutaways, and good camera moves. Because of the documentary style, the cameras are always hand-held and freely moving. If there was a good move from one character to another, I would mark it. So I still tend to mark a lot of reactions and interesting camera work. Because of the use of Script Integration, it’s very easy to get back to any line. If I watch a line and think it’s a good read, I might not mark it because I know I’m going to go back to the script integration in Avid when I edit to compare all the lines before I select one. But if a character does a good nonverbal thing or just anything that’s not really connected to a line in the script but would be a great reaction or a great moment or a great character beat, I’ll mark it. So what I end up with is the Script Integration script in Avid that has all the dailies really well organized on it, clearly laid out, very easy to get to any line and to know what parts of the scene each set-up covers, and then also within those takes I’ll have locators marking great things that aren’t specifically lines of dialogue.

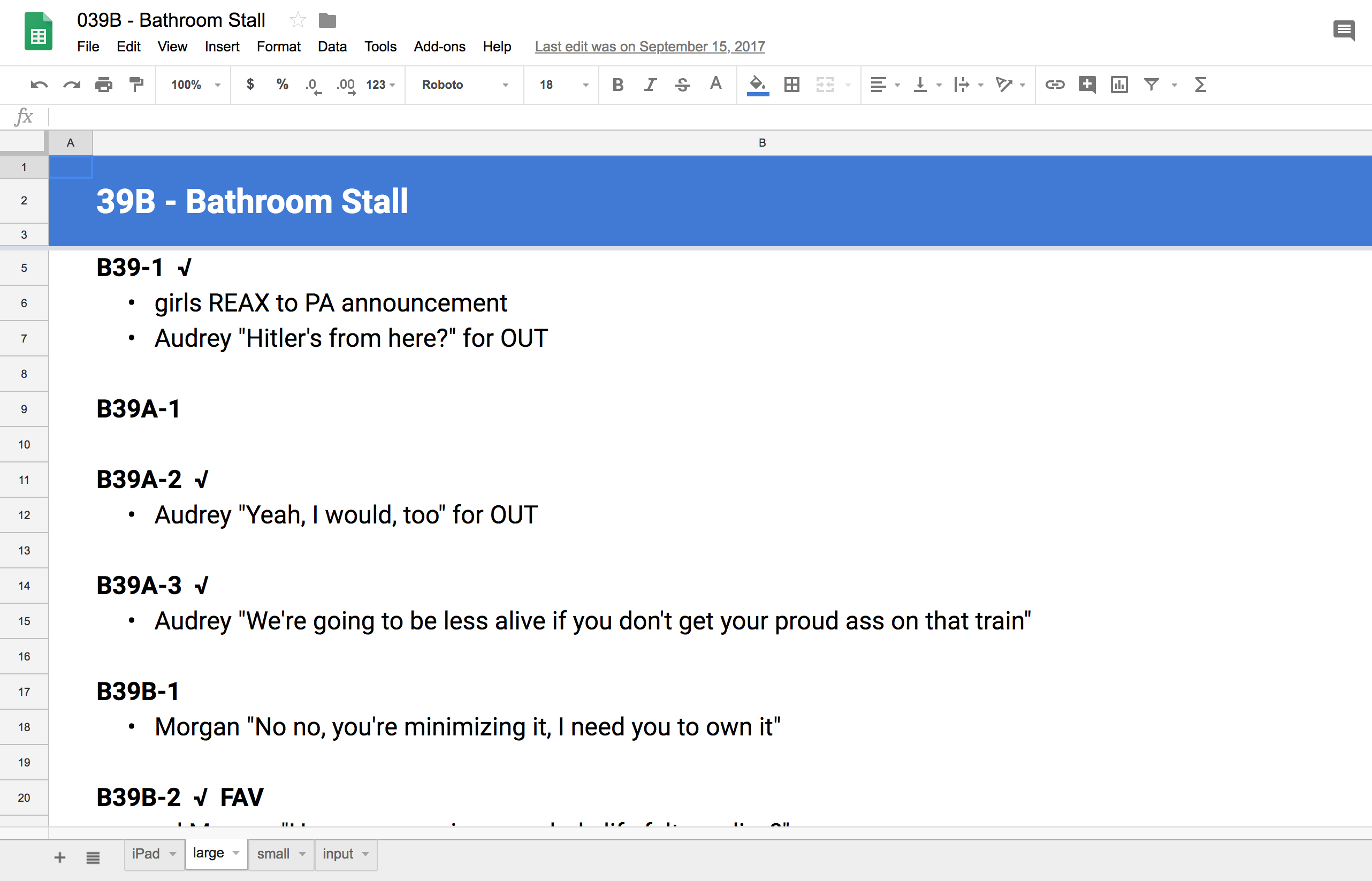

I used to take the locators and write them down long-hand on a sheet of paper. I’d list all of the set-ups and just list out my locators — in part to learn them better. I was one of those kids in college who knew I learned stuff by writing it, so I take copious notes. I transcribed the locators to have a better memory for them, but also I could look over to the list and see if there’s something I missed or might have a vague memory of, like, “The character Sam had a great reaction somewhere.” My shorthand for reaction is “REAX” in caps because I’m often scanning my notes for a reaction that I had located. So I’d scan quickly for “Sam REAX,” find it, pull up the take, and drop it in. What I’ve begun doing recently is exporting the locators from the Avid as a .txt file and importing that into Google spreadsheet (see image below). So now on my desk, I have a little Chromebook that’s on Google Drive, and I can pull up my locators and have them all listed out. Now if I know I’m looking for a reaction, I can use the find function to type in “REAX,” and it’ll highlight all the cells that say “REAX.” I can really quickly find the reactions and look at them. I like to cut a scene shortly after watching the dailies because then everything is still fresh in my memory. In a situation where I might watch dailies and not get to the scene until, say, two or three days later, I’ll pull up the Google spreadsheet of the locators for that scene and read them to remind myself of what caught my eye when I watched the dailies two days ago. And I should give credit where credit is due. The colored locator thing comes from Brent White, who I briefly worked with on It’s Complicated. He was on It’s Complicated as an editor for just a few weeks. I was an assistant editor then and we became professional friends. Before I did Let’s Be Cops — which was my first studio feature — I knew that there would be a lot of improv, so I asked if I could come into his cutting room and see what his system was. He very graciously let me come in, and he showed me a few things, and then I spent another hour or so with his first and second assistants going over their process, which I just completely stole.

I used to take the locators and write them down long-hand on a sheet of paper. I’d list all of the set-ups and just list out my locators — in part to learn them better. I was one of those kids in college who knew I learned stuff by writing it, so I take copious notes. I transcribed the locators to have a better memory for them, but also I could look over to the list and see if there’s something I missed or might have a vague memory of, like, “The character Sam had a great reaction somewhere.” My shorthand for reaction is “REAX” in caps because I’m often scanning my notes for a reaction that I had located. So I’d scan quickly for “Sam REAX,” find it, pull up the take, and drop it in. What I’ve begun doing recently is exporting the locators from the Avid as a .txt file and importing that into Google spreadsheet (see image below). So now on my desk, I have a little Chromebook that’s on Google Drive, and I can pull up my locators and have them all listed out. Now if I know I’m looking for a reaction, I can use the find function to type in “REAX,” and it’ll highlight all the cells that say “REAX.” I can really quickly find the reactions and look at them. I like to cut a scene shortly after watching the dailies because then everything is still fresh in my memory. In a situation where I might watch dailies and not get to the scene until, say, two or three days later, I’ll pull up the Google spreadsheet of the locators for that scene and read them to remind myself of what caught my eye when I watched the dailies two days ago. And I should give credit where credit is due. The colored locator thing comes from Brent White, who I briefly worked with on It’s Complicated. He was on It’s Complicated as an editor for just a few weeks. I was an assistant editor then and we became professional friends. Before I did Let’s Be Cops — which was my first studio feature — I knew that there would be a lot of improv, so I asked if I could come into his cutting room and see what his system was. He very graciously let me come in, and he showed me a few things, and then I spent another hour or so with his first and second assistants going over their process, which I just completely stole.

HULLFISH: I interviewed Brent for Ghostbusters.

So I want to talk about the scene “We’re going to Europe” and this is Kate McKinnon and Mila Kunis and they’re talking about taking off for Europe. There’s a great comedic look from Mila before her final line that I’m assuming you may have pulled from your REAX locators as you were cutting the scene.

SCHWARTZ: Definitely. Definitely. If a character does something that’s great surrounding a line and there’s a chance that I would miss it going back to the script and just clicking on the lines, I would locate it. I know the performance piece you’re talking about. It precedes the line.

HULLFISH: Yes.

SCHWARTZ: She does this great thing and something like that I would totally mark. Mila Kunis is full of those. She’s a grade-A straight man. Her moments of exasperation were fantastic. What I locate is not exclusively reactions but just any moment, any good character moment. Because I know that the well-covered ad libs will be scripted but that the less visited ad libs might not make it into the script, I also mark good one-off ad-libs. If there’s some offhand joke that an actor seems to make just once, I’ll mark it so that, if it doesn’t live in the script, I’ll see it when I read over my notes.

HULLFISH: The other scene that I have is the car chase with the meth-smoking taxi driver.

SCHWARTZ: More credit where credit is due: that scene was cut by Chris Wagner. The Spy Who Dumped Me was shot in Budapest for ten weeks, and I think we were originally scheduled for six days of second-unit shooting. The first action sequence we shot was a big shoot-out in a café — you may have seen pieces of in the trailer. The studio really liked it and had the feeling that there would be some great, legit action in this movie, so the second-unit days ballooned from six to something like twenty. Come the end of production, I was a little behind cutting the action sequences, so we hired Chris to join us for two or three months. He cut the car chase. I tweaked and trimmed as we went forward, but he delivered the beef, so to speak. The idea of that scene is that here are two young women who suddenly find themselves in a high-stakes, action-packed car chase. How would they really feel and react to that situation? The answer is they’d be freaked out. They’d be terrified. So in the editing, we were very careful to make sure that Mila and Kate’s characters are petrified.

HULLFISH: This is not “Bourne Identity.”

SCHWARTZ: Exactly. A big breakthrough for that scene was expanding a joke at the beginning in which Lukas, the meth-addicted driver, reveals that he’s also a DJ and invites the girls to come see him. He turns on his radio, and nowhere was it scripted that the music he plays through his radio becomes the score to the scene. That was Chris’s idea. During his second or third pass of the scene, Chris thought to have the music that Lucas turns on go full and become the score to the first half of the car chase. Chris’s original track there was a really funny, bombastic 90s rap song, and we ended up going with this more Euro-dance song because it really perfectly suited the ridiculous taste in music that this meth-addicted, Uber-driving DJ would have and really perfectly scored the craziness of the beginning of the chase. That’s the magic of the cutting room: taking everything that’s come before you, reviewing it, seeing what you can do with it, and then adding to it with new ideas. To me, that’s the great fun in the cutting room.

HULLFISH: The improv that you deal with in cutting a feature must really add another level of complexity to the editing.

SCHWARTZ: Yeah. It’s a burden and a gift. And both are very well demonstrated by the film Mike and Dave Need Wedding Dates, directed by Jake Szymanski. It starred Zac Efron, Adam Devine, Anna Kendrick, and Aubrey Plaza. At any point in time, there were two or three on-set writers coming up with different ways of doing a comedic beat — as in, having the same story beat occur, but with completely different dialogue. Jake shot a ton of footage. I routinely got eight and nine and ten hours of dailies a day. Early in production, with so much ad lib to work with, I really didn’t know where to take some scenes. So I started cutting it all together! I started editing these mega-scenes in which I wove together almost all of the ad-libbed beats. One good example: there’s a scene where Mike and Dave are arguing with their dad outside of their hotel room. The scene in the movie is maybe a minute long, but the first pass of the scene was more like eight minutes long because there was just so much grist for this argument. There were so many joke ideas that Jake and the on-set writers came up with and explored. Jake loved the eight-minute cut and said, “I love being able to see all this stuff.” So I ended up cutting these incredibly long scenes by finding ways to work together all the ad lib beats. Jake cross-shot much of the movie, so a lot of these beats weren’t technically difficult to edit together. Both characters were being shot at the same time, so if there’s a really good joke, you can just cut from one camera to the other, and there’re no continuity problems to worry about.

The editor’s cut of Mike and Dave Need Wedding Dates was a little over five hours long. It took Jake and me three sessions over a full day to watch it, and then we went about whittling down the movie. For a number of weeks, we were whittling down the movie based on what jokes felt good. We screened the cut for some close friends a couple of weeks into the process — I think the cut at that point was two hours and 45 minutes. A comment that came out of that screening was very astute: that there wasn’t a lot of differentiation between the four characters, that it’s basically four young people at a destination wedding who were making a lot of jokes. Many of the jokes were funny, but who were these characters? For example, Mike and Dave are brothers. How are they different? How did their goals conflict? We’d been reducing the length of the movie, but we hadn’t been sharpening the story or the characters at all. So we changed tack and started from square one. Based on the footage we had — and because there was so much ad lib, we had really quite a large range of character beats — what could we do with these characters to differentiate them and enhance the story? We made Aubrey’s character a little meaner. That made her romantic storyline with Adam’s character more engaging. We reversed the ages of the brothers because it served the story better and we had the footage to do it. We could choose performances that made one seem like the younger brother even though he was scripted as older, which changed the brothers’ dynamic and changed the story. So that’s the blessing of having so much ad lib, that you have a lot of material to work with.

Of course, the curse is that you have a ton of footage to go through. For example, the movie I’m cutting right now is called Stuber and stars Kumail Nanjiani. Yesterday, I was working on a scene in which Kumail, an Uber driver named Stu, is called Stuber. Kumail is a really smart ad-libber, and he ad libs different responses to being called this demeaning nickname. What I’m working on with the director right now is how meek or strong Stu should be at this point in the story. Because of all the ad-libbed reactions, we’re able to really dial in over a huge range from very subservient to totally contrary. It’s a lot of work at the front end because you have a lot more to work with, but there is a lot more you can do down the road because you have a lot more to work with.

HULLFISH: A lot of it is contextual. You can think that this individual scene is a hysterical scene. But then you realize, with the scenes around it, that you also have to be driving to a specific emotional direction or story direction.

SCHWARTZ: Steve, that’s a perfect segue into the one theory I have about editing comedy that I think is worth anything! This is the one thing I thought of that might actually be a half decent insight. I divide humor into two categories: micro-humor and macro-humor. Micro-humor is self-contained humor. It’s stuff that is funny in and of itself: a pratfall, a pie to the face, a pun, a daft pop-culture reference. Macro-humor is stuff that’s funny because of the context, because of what we know about the characters and the story that we’re watching. For me, the perfect example of macro-humor is the last five minutes of any episode of Seinfeld. The last couple of minutes of an episode of Seinfeld is always comprised of short scenes with just a few lines of dialogue. They’re hilarious if you’ve been watching the episode, but if you haven’t, you have no idea what’s going on. George answers the phone and says something grumpily and the audience goes crazy laughing and you’re like, “What’s so funny?” That humor in the final minutes of an episode of Seinfeld is completely based on the context of the story that we’ve seen unfold. Both micro- and macro-humor are important and both need to be utilized. But what I’ve found is that macro-humor doesn’t work unless it works with character and story. If a macro joke is attempted and it doesn’t work, it’s probably because we haven’t set the characters up well enough or we’re not invested in the story well enough. Fixing a macro-humor joke means fixing how we’ve presented the characters or stories. Whereas with micro-humor, the joke or the beat can be funny while contradicting character and story. A perfect example is when a character says something that in-and-of-itself is funny, but, would that character say that in that moment? Are you working toward the story you want to build in this moment by having that character say that line or is it actually counter to it? The risk is that, because the micro-humor is funny, you keep it even though it is contradictory to the larger goal of a cohesive story and fleshed-out characters. For example, Kate McKinnon is always saying something hilarious, but we had to make sure the micro-humor wasn’t working against the character we were building.

HULLFISH: An example of that — since you’re talking about trying to have real reactions of these women, and an honest reaction to being in the middle of a gun battle — she might say something that is hysterical, but would never be something a real person would say, so you don’t want to use it because that takes away from her real reaction.

SCHWARTZ: Exactly. There’s a scene in the movie in which Kate and Mila are tied up and about to be tortured for information. Kate said a lot of very funny things. If you tie her to a post and put a camera on her, she’s going to say a lot of funny things. In my editors cut, I used a lot of them — not because I felt like they should survive for the whole editorial process and be in the movie, but because we shot them and Kate said them and they were funny! I try to be a little more inclusive in the editors cut just so we can see what’s there before eliminating it. But pretty quickly we realized that that character wouldn’t have the presence of mind to say such witty things. The inclusion of those lines diminished the intensity of the scene. I think the master of micro-humor is David Wain. A movie like Wet Hot American Summer, which I love, if full of jokes that feel like micro-humor and meta jokes. So you enjoy the movie for these comedic, meta things. There’s a ridiculousness to the story and characters because the style of humor keeps the characters and story in a kind of ridiculous zone. In a movie like The Spy Who Dumped Me, you have to make sure that the micro-humor doesn’t prevent the characters and stories from feeling real.

HULLFISH: That’s great wisdom right there. Tell me a little bit about the schedule for the movie.

SCHWARTZ: We started shooting July 3rd in Budapest, and the shoot ended September 8th. The last week or so of shooting happened in other European cities. For the last week of production, my first assistant and I flew back to Los Angeles, and production went to Berlin, Prague, and Amsterdam for a little bit of shooting in those three cities. We were editing in Budapest during production, which was fantastic. We cut at a very sophisticated facility in Budapest called ColorFront with as cutting-edge equipment as one would expect anywhere in the world.

HULLFISH: Avid, I’m assuming?

SCHWARTZ: Yeah. It was great for me to be in Budapest because Susanna is very collaborative. She’s the kind of person who wants other people’s opinions. She’s not challenged by other people’s opinions or disagreeing thoughts. She wants to incorporate the best thinking around her into what she does. So I was frequently a sounding board for her. A couple of times, she called me to set just to be on-hand as a second opinion for the angles she was shooting. Once or twice she called me up in the morning and said, “Hey, we’re shooting such-and-such this afternoon. I’m thinking of this angle and this angle. Is that going to work?” I got to be a sounding board in that way and, as an editor, it’s incredibly gratifying to be able to provide input on what you’re going to get the next morning.

HULLFISH: So you move back to LA and you’re still getting dailies from these other cities in Europe. How were you getting dailies? Are they going through ColorFront?

SCHWARTZ: That’s correct. We had a local second assistant editor named Mercedesz Czanka. She’s a young woman in Budapest, and she’s fantastic. Anyone reading that is going to be working in Budapest, hire Mercedesz Czanka. She continued working on the film after we left Budapest, doing our dailies in Budapest and sending us bins. The media would was transferred from Budapest, as well. We got dailies from her as though she were in Los Angeles. It was really seamless.

HULLFISH: And you finally got to mix and DI around…?

SCHWARTZ: Mix and DI happened in mid-March.

HULLFISH: And did you have a lot of screenings? Is that something really critical for a comedy?

SCHWARTZ: Screenings are critical for comedies.

HULLFISH: And since I know you worked with Brent White, he videotapes the screenings and then matches the videotape of the audience reacting to his cut.

SCHWARTZ: Yes, we do that it. When I was an assistant editor, we would audiotape the audience, and in the past five years or so, we’ve started videotaping the audience. The morning after the preview, I have my assistant editors import the video of the audience into the Avid and make a sequence that has a picture-in-picture: what’s big is the audience and what’s small is the movie. We watch the audience watch our movie. It’s really informative and I’m sure that whatever Brent told you, I’ll just repeat because my appreciation for test screenings came from a Paul Feig Interview. He likened test screenings to doing standup comedy where the goal is to have ten good minutes of material. You keep trying stuff in front of an audience until you know your ten minutes are solid, and that’s also what you should do with a movie. The goal is to have 100 or 110 solid minutes, and you keep putting what you have in front of an audience until your minutes are solid. I think when I was younger I absorbed a sort-of auteurist argument that test screenings were ruining films, that a film should be the unique expression of an artist. Perhaps in other genres that is true, but I think in comedy it’s really important to put your movie in front of as many audiences as you can to see what works and what doesn’t. I’m always surprised. There’s always something that I think just isn’t that funny and the audience goes crazy for it. Or there’s something that I think is the funniest thing in the world and it gets no reaction from the audience. The more people that you have to confirm or refute those instincts, the more appealing your film is going to be to the ultimate audience.

On The Spy Who Dumped Me, we did several friends and family screenings. We did maybe six during the Director’s Cut, and those were really helpful. Those are smaller — like 20-person audiences. Susanna is not just a director, but also a writer, so she has a lot of writer friends from whom we got a lot of really good feedback. Their feedback really helped to shape the film, and then we only did two recruited audience preview screenings which, in my experience, is not many for a comedy. I feel like comedies should have at least three previews with large, recruited audiences. And I think the other comedies I’ve worked on have had four or five, which is really valuable.

HULLFISH: You mentioned a couple of times your assistants and how much they help you. What’s a skill that you value most in your assistants?

SCHWARTZ: That’s a tough question to answer because, at this moment, there are two skills that I value. Blair Miller, my first assistant editor who I’ve been working with for three projects now, is a very talented editor. He’s edited a couple of features of his own. I lean on him for a lot of sound work and, to the extent that I can, doing passes of scenes. On The Spy Who Dumped Me and on Stuber, he did the first pass of several scenes, as well as incredible sound design on all the action sequences. I will cut picture to an action sequence and give it to him, and he’ll do a fantastic job putting in all the sound effects. Starting with The Spy Who Dumped Me, we started cutting in 5.1 surround sound, which is so much fun and so cool and so easy on the Avid.

HULLFISH: I just talked to Craig Wood who cut Ant-Man and The Wasp and he said he’s been cutting in 7.1.

SCHWARTZ: With the surround-sound panning in the Avid, there’s literally a box and you pull a dot to where you want the sound to be in the room. It’s really fun. Blair does a great job with the surround sound in the car chases with cars zooming from behind and in gunfights with the bullets coming from all directions. I really value his editing abilities. I’m generally kind of a control freak, so Blair is really the first assistant editor that I’ve worked with who I’ve leaned on so much creatively. He’s fantastically talented and I’m super happy to be working with him. Lauren Brown is my second assistant editor. This is my first time working with her. She has the skill set that I most appreciate in an assistant editor, and that’s having a strong work ethic: being organized, being punctual, being communicative, being able to learn pretty quickly the tasks that are specific to my idiosyncratic way of working, being able to work with me to internalize my specific scripting rules, and then being really responsible about her work. If there’s something that needs to get done, she sees it through to completion. If I ask her how long it’ll take her to do something, her estimates are quite accurate. I think it’s valuable for assistant editors or people who want to get into editing to know that that is skill number one when you get your foot in the door because anybody can practice a good work ethic. It doesn’t take any sort of magical artistic spark. And it’s important to practice that as an assistant editor because being an editor is also ninety percent work ethic. Maybe ten percent artistic spark.

HULLFISH: Thanks so much for your time.

SCHWARTZ: I’m really excited to be in a Steve Hullfish interview. When I google editors, an Art of the Cut interview usually comes up and it’s the most valuable resource.

HULLFISH: That’s a lovely compliment, Jonathan. Thank you. I really appreciate your time.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish. There are also a few exclusive, additional questions and answers from this interview over on Frame.io

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish. There are also a few exclusive, additional questions and answers from this interview over on Frame.io

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now