Jay Cassidy, ACE, has a list of awards that are longer than most editors’ filmographies. He won the ACE Eddie in 2007 for Best Documentary for An Inconvenient Truth. He was nominated for another Eddie and an Oscar in 2008 for Into the Wild. He won the Eddie and was nominated for an Oscar in 2013 for Silver Linings Playbook. He also won an Eddie and was nominated for an Oscar in 2014 for American Hustle. He was nominated for another Eddie in 2016 for Joy. (I interviewed one of his co-editors, Tom Cross, about that film, here.) And he won an Emmy and was nominated for an Eddie for the mini-series, The Beach.

I talked to him about his latest film, A Star Is Born, and because of the unique audio requirements and workflow – and because Jay wants to spread the credit to others on his team he feels deserve the attention – Jay wanted to include Re-recording mixer and music editor, Jason Ruder and Jay’s first assistant editor, Mike Azevedo in our interview.

Ruder’s previous credits – in various roles – include Transformers: The Last Knight, Patriot’s Day, La La Land, Whiskey Tango Foxtrot, and Entourage.

Azevedo has also assisted on The Cloverfield Paradox, Foxcatcher, Fury, American Hustle, and Silver Linings Playbook.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: Jay, it’s so great to finally interview you. I saw the film and loved it. Thanks for including Jason and Mike!

CASSIDY: When I read through your interviews, I always learn something. Your pieces are allowed to be long, tend to go into more detail and there’s an implied intelligence in the readership. So I thought, we’ve got to come up with something out of A STAR IS BORN that is worthy of your column. Certainly, the thing in the post-production that’s as distinctive as anything — it was kind of the biggest challenge going in — was for us to preserve the live vocal.

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about why it was decided to record vocals live during filming and — when you were told that — what you thought would be the technical difficulty of pulling that off.

CASSIDY: Lady Gaga (Stefani Germanotta) and Bradley (Cooper, director/actor/singer) both wanted it. Stefani doesn’t like to do playback for music videos and shows that she’s done — she says she’s just not good at lip syncing. And Bradley created his own singing voice for the role based on the character and that voice would be more authentic if it was recorded while he was in character, performing on the set.

They both felt more comfortable with that approach and felt that it would just be more real. They didn’t want what happens in many musicals; the song begins and there’s an aural suspension of belief because of a subtle disconnect between the lyrics being sung and the picture.

Jason (Ruder, Supervising Music Editor and Re-recording Mixer) started on the film before any of us. He attended the pre-recording sessions with Ben Rice, the music mixer where Bradley, Stefani and the other musicians – Lukas Nelson and his band, “Promise of the Real” – worked out the songs to be performed on camera. Jason, you should probably talk about that. Then we can describe what Steve Morrow, the location recordist, did during the shoot.

RUDER: We wanted to make sure everything in preproduction that was done in a recording studio — that would transfer to set — would carry through to post: that we were using the same microphones, through the entire process even though we were picking up live vocals. There was a sound they were used to getting in a recording studio, so even though we pre-recorded some of the band we thought, “Hey we’re going to mic them all in every scene” — mic the drums mic the bass, mic everything. And somehow, the sound, you could sort-of interchange a little bit with the band if you picked up something cool on set with a guitar, we knew we were using the same mics, the same placements, the same amps,

RUDER: We wanted to make sure everything in preproduction that was done in a recording studio — that would transfer to set — would carry through to post: that we were using the same microphones, through the entire process even though we were picking up live vocals. There was a sound they were used to getting in a recording studio, so even though we pre-recorded some of the band we thought, “Hey we’re going to mic them all in every scene” — mic the drums mic the bass, mic everything. And somehow, the sound, you could sort-of interchange a little bit with the band if you picked up something cool on set with a guitar, we knew we were using the same mics, the same placements, the same amps,

CASSIDY: And all of the music was based on a click track.

RUDER: Everything was to a click track, so you could cut between takes. And with vocals, it’s amazing how sonically sensitive Bradley is. If you were to change a mic on a part of a vocal he would catch it.

CASSIDY: We were dealing with a remarkably sensitive palette.

RUDER: His ears are incredible. He’s like a seasoned record producer. So it was really important to just make sure that if we had to pick up vocals or try something new or a cut between takes, that every single step of the way, there was continuity in all of it, just to make sure we could edit it all later.

CASSIDY: And also preserve the sense of realism from the location. That was the mantra all the way through. If it was a big concert or singing to a small group of people, it should feel real.

RUDER: That was Stefani’s main concern. When she hears things in movies, the environment doesn’t sound real, so we did a lot of planning. We shot impulse responses for every single venue we went to, even if it was the church scene, or a big venue like The Shrine, we took the time to quiet the set and run tones around so we could create our own spaces and ambience later.

HULLFISH: Could you explain that? Explain how an impulse response can be used to recreate a space.

HULLFISH: Could you explain that? Explain how an impulse response can be used to recreate a space.

RUDER: Most of the reverbs and ambiences were done in Altiverb (a ProTools reverb plug-in) for this film, and you can make your own impulse responses for it. Like, if we shot at The Shrine or Coachella, if you put up enough mics you can run a tone through the speakers, broadcast it through the environment, capture it back through various mic placements and create an algorithm later that can be programmed so that when you leave Coachella or Stagecoach, we can re-create our own reverb for that space. So all the reverbs are really authentic. All the spaces are really authentic. Which is good, because, between the memories of Gaga and Bradley, they would get into post and listen to something and say, “Wow, that actually sounds like it did on the day.” And if we tried to switch a reverb or enhance it for creative purposes, one of the two of them would say, “Wait a minute. That didn’t sound like that.” That’s how sonically sensitive both of them are.

CASSIDY: We didn’t lack for experience. Jason had done LA LA LAND. Our sound recordist, Steve Morrow, had done the location recording on that film as well. But that was a completely different musical approach.

RUDER: Yep. It was weird because when I started in post on that and I just got handed a bunch of sound rolls, it took me quite a while to get my head around it. LA LA LAND had its own authentic live vocal quality.

I think it was more important on this one because they were writing the songs up until the morning they were shot. So there were so many versions and so many things changed at the last hour. All of that had to be prepped for playback. Many times, I’d show up on set with three or four versions of a song. Stefani wasn’t always sure what key she’d want to sing something in that day, so you’d have to be ready to change things on the fly. There were a lot of moving parts I think more so than any film I’d worked on in the past, just between the songs being worked on and finessed right up to the end, all the environments, and just the ears between the two of them.

HULLFISH: It’s fascinating that you had to prep multiple keys for songs.

HULLFISH: It’s fascinating that you had to prep multiple keys for songs.

RUDER: We had different tempos for many of the songs as well. She would go back and forth on whether something should be 106bpm… “no, try it at 107, try it at 108.” So literally, I’d walk in with 10 different versions and need to call up anything at any moment. Steve Morrow is great. We had 64 channels of production sound mixing in a lot of cases.

CASSIDY: So, in theory, every time I pressed play on a take, instead of just getting maybe 8 tracks of audio, I could be getting 64. We had to adjust the dailies workflow to accommodate. We had designated the first eight channels as the normal kind of production channel and one playback was on the first eight. Mike (Mike Azevedo, 1st Assistant Editor), you oughta talk about that because it was like doing gymnastics just to get the material into the Media Composer to even begin to deal with it and also leave a trail so you could get back to it.

AZEVEDO: What Steve did on set is feed LTC timecode from the ProTools rig (longitudinal timecode is an audio-based timecode track) to his recorder. That would be on A9 and the first thing I would do was import everything. The lab that did the dailies would just provide a mono comp track on A1, but we would bring in all WAV files from Steve. The Media Composer could read the LTC track and add it as a separate auxiliary time code. That was the first little trail of being able to get back to the playback session because obviously, sync is very important in a film like this. We would then make sub-clips with the production tracks and then any sort of vocal mics that we felt we would need at the time and that worked pretty well for us most of the time, but occasionally you’d have to go digging back, but not often. When we would finish scenes we would send them over to Jason, and Jason — on the days that he wasn’t on set — would mix them.

CASSIDY: Even before Bradley ever saw anything in the cutting room — the songs in my cuts of scenes would have a mix pass by Jason, using the exact takes that we had chosen for the vocals as a place to start. From the beginning, we decided that the picture editing cutting room would be a 5 1 environment and then we matched the speakers with Jason’s. Once we did that, his 5.1 mixes would just drop right in. So when Bradley saw it, even the most roughly assembled picture cut had a 5.1 mix to it from Jason. The whole “Northern California” song sequence: “Alibi” through “Shallow” — which is about 11 minutes – was all mixed in the first assembly. It was useful to do that on a music film; it’s hard enough to make a movie and tell the story without requiring that suspension of disbelief: “OK, this music will be great someday…” Jason’s first mixes were not that far from how they are in the final film. From the first assembly, I’d say we were at 80 percent of the way with the mix and there are, depending how you count them, 15 songs. To have that music mixing and editing from the very beginning saved a lot of heartache and delays. It meant that when we went into early screenings the songs sounded great. Going into the temp dubs, the music mixes were prepared and dropped right in. That was really necessary because when we did turnovers, we were turning over 40 tracks! Mike and Christian Wenger (the Assistant Sound Editor) worked out a system at the beginning because they could see the train wreck ahead.

HULLFISH: What tracks were you carrying in the picture? And then how did you match back to all of the recorded tracks that weren’t in the picture cut?

AZEVEDO: So all of the sub-clips and groups carried the first eight production tracks. Occasionally we’d have five or six or however many characters were in the scene plus a boom or two booms or whatever it was. The way that Avid Media Composer organizes this material internally is that when you go to turn it over, no matter if you have one track on the timeline or all 42 or 64 or however many tracks you have, it links to all of them. If you imported them all — even if the sub-clip only uses a single audio track, and we found that out because normal reels that didn’t have music in it would export fairly quickly, but if you had a reel with even one music piece in it, the turnaround was much longer because it was gathering and exporting all of those many music tracks. Christian would take our AAF and they had predetermined what tracks every day were music tracks and what tracks were relevant to the sound department. And he had the difficult job keeping track of an enormous number of audio tracks. We tried to make it as simple of a workflow as possible. Steve was very good about labeling everything as it went into the recorder. So for Christian, he knew he didn’t have to worry about carrying something like the stereo drum channels that were was recorded on the set, so he had a lot of tracks that he could throw away.

The other thing that we did is – instead of giving the sound team embedded audio media each time we exported a cut – we gave them ALL of the imported sound roll MXF media so that we could just send linked AAFs to everybody and it made the process so much smoother because each turn-over would have been like 20 or 30 gigabytes of just sound. We decided really early on that there was no way we could do that.

The other thing that we did is – instead of giving the sound team embedded audio media each time we exported a cut – we gave them ALL of the imported sound roll MXF media so that we could just send linked AAFs to everybody and it made the process so much smoother because each turn-over would have been like 20 or 30 gigabytes of just sound. We decided really early on that there was no way we could do that.

CASSIDY: And we turned over reels quite early, in order for Christian to have time to sort things out. So even if he had to conform the reel, he had already done the hard work of sorting the basic tracks. You can approach the turnovers – thinking about it beforehand and anticipate the problems – with a plan or you can just dump it on the next department. (groups laughs) It paid off because we had some very quick turnarounds with temp dubs as we were working through the picture editing and everybody wasn’t having to reinvent the wheel each turnover.

HULLFISH: It shows, because you guys were all still talking to each other.

RUDER: That’s right.

HULLFISH: What were you guys doing for change lists or were you using something like Conformalizer? How were you updating those changes as you made picture changes?

AZEVEDO: I would send change lists to everybody.

RUDER: The initial turnovers — remember Mike? — when we got a massive turnover like that I’d want every single take assembled. Mike would have to make these massive AAFs. If we did five or six takes used in one song….

AZEVEDO: We would conform each take to whatever the picture cut was and use the LTC track because that was consistent among all the takes and we would just pop them in so you’d have six takes of SHALLOW.

RUDER: So my first assembly would be 64 tracks times 6 (384 tracks!). A lot of that you can get rid of quick, but when you when you start going through it you want all of the live vocals. You want all the ambiance tied to those vocals. You want any crowd mics because it all has vocal bleed in it. To do any kind of vocal comping, you might not need all 64 tracks, but you might need 24 or 30. We wanted all the ambiance. So the first assemblies were just enormous.

RUDER: So my first assembly would be 64 tracks times 6 (384 tracks!). A lot of that you can get rid of quick, but when you when you start going through it you want all of the live vocals. You want all the ambiance tied to those vocals. You want any crowd mics because it all has vocal bleed in it. To do any kind of vocal comping, you might not need all 64 tracks, but you might need 24 or 30. We wanted all the ambiance. So the first assemblies were just enormous.

HULLFISH: Jay, what were you actually carrying in your Media Composer timeline for a typical music piece? What were you editing picture with?

CASSIDY: The timeline had maybe four or six monos and then some stereos and then 5.1 The first mixes from Jason would be the song plus the crowd, each as a 5.1 mix. That would be our first pass on it. That was enough because if something changed with the music we usually ended up just getting a new mix. You don’t want the picture editor fooling around with the lyrics of the song. It was a big enough job that we really had to maintain a strict kind of breakdown of who did what. And I did not want to start doing any sort of music editing tasks other than the most broad-based slash-and-burn type things. Like the long pre-lap of the Northern California sequence – the instrumental of ALIBI – we had to keep extending out into the picture, and I cut it in beat and get it sloppy, and Mike, who has a very good background in music as a choral singer would come in and bless it, but knowing full well it was going right to Jason and he would work it over even more and then it would come right back to us and that’s the right use of everybody’s time.

We made some experiments during the picture cutting where we tried to cut down a song or two and we would do it ourselves and it would either work or not work. And if it did work, we’d send it to Jason. You have to realize that you only have so much time to make a film. I don’t want to be doing too much sound effects work. I like to pitch that over to Mike or another person in the picture editing department or even — if the sound editors are available early — let them do it and they’ll send you back something that is much better than you can do yourself. And plus they could then carry that work and be that much further along.

After the film was shot, Bradley was in the cutting room full time, your time is his time and it’s his time to experiment with the movie. And for that time, you have to have the team built and functioning so that you’re not caught in front of the director doing some mechanical thing that someone else could be doing.

After the film was shot, Bradley was in the cutting room full time, your time is his time and it’s his time to experiment with the movie. And for that time, you have to have the team built and functioning so that you’re not caught in front of the director doing some mechanical thing that someone else could be doing.

HULLFISH: How quickly were you getting those turn-around mixes when you would send off a cut and then what were you doing? Were you bringing those back in and having a whole layer of your own muted production tracks and then just have the temp mix from Jason on a soloed mix track?

CASSIDY: Somewhere in the dialogue track we would carry the production track that had some version of the music. Not usable except as reference – some of the playback tracks had a click on it. We kept them muted. The useful reference may not even be the music but the playback timecode. It was easy if you made a picture change you had a sync reference right there that you could go to. So we kept those things muted and then Jason’s mixes would be there in a day or two in most cases.

RUDER: Usually it was a day… if it was a montage with one track fading into another and another, then that would be a few days because it was so much track management.

CASSIDY: And once Bradley had finished shooting was working with it, he would have some very specific thing he wanted and he’d get on the phone, tell Jason what it was, and we’d have the new mix in a couple of hours because the track was all prepared. It was very efficient.

HULLFISH: How were you monitoring 5.1 with Bradley in the room? Were you sitting next to each other in the 5.1 field? Did you have one monitoring set-up for when he was there and another when you were by yourself? A lot of times, the editor is at 90 degrees angle to the director, then the 5.1 is thrown off.

CASSIDY: The room that we worked in was configured like a little screening room – screen, sofa in front and the console behind the sofa. The room was a little small and we didn’t use the surrounds because they would have been way too close behind me. So we just left-center-right and sub in the cutting room. Then Bradley would go to Jason room has a whole 5.1 setup and he would listen to some mixes here. (We recorded this interview in Jason’s mix room via Skype.)

I can’t imagine not working with 5.1 ever again. It’s so easily transferable. I remember when I discovered in 2014 that you could make a 5.1 track in the Avid and set the mixer to monitor 5.1. No more direct output and the nasty outboard mixer. Sometimes the Avid is more facile than the particular user, tools that make the workflow better exist but us dumb editors’ may not know about them. We felt really stupid for not knowing about the 5.1 tools because they had probably been available in the software for a few previous films.

I can’t imagine not working with 5.1 ever again. It’s so easily transferable. I remember when I discovered in 2014 that you could make a 5.1 track in the Avid and set the mixer to monitor 5.1. No more direct output and the nasty outboard mixer. Sometimes the Avid is more facile than the particular user, tools that make the workflow better exist but us dumb editors’ may not know about them. We felt really stupid for not knowing about the 5.1 tools because they had probably been available in the software for a few previous films.

The toolset of the Medial Composer is moving so fast that if I find myself doing exactly what I did on the previous film, I get nervous that I’ve missed a particular new tool that would make my life simpler. Small things that have been added in the last few years turn out to be life-changing; SELECT RIGHT, NEVER SELECT FILL WITH THE SEGMENT TOOL, DUPLICATING CLIPS DIRECTLY ON THE TIMELINE. I could go on…

RUDER: I remember it was like the second week of the editor’s assembly we played Bradley back a mix and he’s already giving notes on reverb perspective and drying up the vocal on close-ups. He could start commenting on that stuff straight through the director’s cut. By the time we got to temp mix one, all those decisions were made. He started to really hone in on everything.

CASSIDY: And because Jason was also the music mixer on the film, the work he would do in his room was easy to carry downstairs to the re-recording stage.

Every time you do a movie, there’s a new process or format and because of timing and whatever, you haven’t used it. I’d never done a film in Dolby Atmos and it was always pitched to me as an “additional print master.” But just doing that doesn’t take advantage of the power of its design. And, these things are always discovered the hard way.

We’d done the final mix in 5.1 and 7.1 and the studio was all happy. And then we go into the Atmos room to “print master” and we discovered we were on new ground. At first, Bradley was really suspicious of Atmos. Then he got plugged in and loved it. He could hear stuff that he couldn’t hear in the 5.1 and 7.1 It quickly became: let’s remix the movie. Let’s take advantage of all the Atmos objects, especially with the music. So we did the Atmos mix then folded that mix to create a new 7.1 and 5.1, through the RMU box. There was a real learning curve to rearranging the workflow mid-stream. No question that the final result sounded better.

HULLFISH: Do you think that’s the advantage of editing in 5.1 is that you’re getting a better sense of the sound so that when you’re going to the mix room you’re not starting over from scratch almost?

HULLFISH: Do you think that’s the advantage of editing in 5.1 is that you’re getting a better sense of the sound so that when you’re going to the mix room you’re not starting over from scratch almost?

CASSIDY: I think 5.1 is valuable — especially for us — because of the music. And, as you well know, in the Media Composer, you’re cutting music and sound effects and dialogue and you’re creating your own little mix for screening purposes before you’ve ever done a temp dub. Depending on the set-up of the room, Avid mixes can be quite good. The 5.1 just gives you a little wider palette and every film I’ve done since our moment of truth in 2014 has been done in 5.1.

AZEVEDO: Sometimes you have the advantage of working at a facility with a 5.1 screening room on-site. You can walk down the hall and playback the whole film in 5.1, and get a theatrical experience. Once you get to the point where you have a temp dub, the 5.1 stems can live on your timeline, and as the recutting occurs, new material can be integrated into the 5.1 mix easily, so your next screening is not a step backward from temp dub.

HULLFISH: But your editing room itself was left-center-right?

AZEVEDO: Yeah and a subwoofer.

HULLFISH: You mentioned matching the speakers. Are you talking about somehow trying to run tones through them and getting them to match aurally somehow?

CASSIDY: Jason’s has a certain brand of speakers in his room here and they’re good.

HULLFISH: So what are they?

RUDER: They’re 5.1 Adams with a pretty large sub. It’s a pretty flat speaker. It’s close to a JBL on the dub stage and because of Bradley’s sensitivity, he was noticing the color difference between the speakers in Jay’s room and my room. So after the second week, we said, “Let’s not fool around. Let’s just get the same speakers in my room.”.

HULLFISH: So it was a tonality and color thing.

HULLFISH: So it was a tonality and color thing.

CASSIDY: We had to match the speakers because we were trying to judge Jason’s work and after we straightened out the speakers, it went back and forth between the rooms seamlessly.

RUDER: The hard part was the low-end management. Mike would pink the LCR and it would all be at 85, it took a while to get the sub. Those bigger performances, like the Coachella stage — we were kind of getting thrown — because Bradley’s trying to give mix notes on lower end speakers originally and the rooms are different.

HULLFISH: So for someone who is not an audio expert, when you’re saying that you pink the room, you’re using pink noise which is like white noise but all the frequencies are the same amplitude, and then you feed that through the speakers and then use a device that allows you to match the speakers using the pink noise.

CASSIDY: Great VU meters available for the iPhone. Put it down in the sweet spot and play the pink noise and adjust the speakers.

RUDER: Room acoustics notwithstanding at least level-wise and speaker-tonality-wise you’re as close as you’re going to get.

HULLFISH: As someone who has performed to pre-recorded music, I’m guessing that the performance was affected by the fact that they were delivering a live vocal performance in front of the camera.

CASSIDY: In our case, when they were hearing on their in-ear monitors, they were hearing themselves live and the backing tracks.

RUDER: That was a hard thing to figure out on set because the initial playback mix during recording didn’t go well, so we had to bring in GaGa’s concert in-ear monitor mixer, because he was so used to delivering what she was expecting to hear in her ear. Originally, she wanted to record with the speakers on-stage playing back at concert volume.

CASSIDY: Some of the concerts were done semi-publicly. Like at Coachella. Everyone in the world has cell phones and even if you own the extras somebody is going to sneak one in and there was great sensitivity about putting the songs on the PA. The fear was if they played the tracks through the PA to the crowd, then it would be up on the internet.

CASSIDY: Some of the concerts were done semi-publicly. Like at Coachella. Everyone in the world has cell phones and even if you own the extras somebody is going to sneak one in and there was great sensitivity about putting the songs on the PA. The fear was if they played the tracks through the PA to the crowd, then it would be up on the internet.

HULLFISH: So the monitoring on onstage — in order to get a nice clean vocal track — you couldn’t have 120-decibel rock concert PA sound. Did they completely mask the audio — only putting it to the in-ear monitors? Was there any sound coming through speakers?

RUDER: It was pretty much completely masked. We didn’t let the songs come through the speakers at all. For the bigger venues, we would get, like, 500 of GaGa’s monsters (her fans…) in the front for crowd. She’s singing full-out and he is too, so they’re going to hear the vocal but they’re really not going to hear the track with it. All of those people had to bag their phones when they went on set, to keep it from getting recorded. But we didn’t want to go out to Coachella where there were tons of people and blasting songs that weren’t getting released for a year and a half. We were extremely careful not to be broadcasting those original songs out.

HULLFISH: So when she’s singing the people that are in a crowd can literally not hear her?

RUDER: That’s true. I mean they could enough, even though nothing was coming from the PA.

CASSIDY: It’s a big concern and it makes it difficult to do the movie sometimes because there was this protection on the music tracks — there was audio watermarking which is just a nightmare, but it had to be done.

HULLFISH: You guys had audio watermarking on the tracks in the edit suite?

AZEVEDO: We didn’t have water-marking on any of our tracks. However, any time we sent music to anyone besides Jason and the sound department here, any vendor — marketing, our DI facility — they all received watermarked audio. Essentially, it’s a constant broad-spectrum noise that’s inaudible, but detectable by software. If anything were to leak, it would be possible to identify the person who had downloaded the watermarked file.

AZEVEDO: We didn’t have water-marking on any of our tracks. However, any time we sent music to anyone besides Jason and the sound department here, any vendor — marketing, our DI facility — they all received watermarked audio. Essentially, it’s a constant broad-spectrum noise that’s inaudible, but detectable by software. If anything were to leak, it would be possible to identify the person who had downloaded the watermarked file.

HULLFISH: What are some of the challenges to these musical performances and editing them picture-wise?

CASSIDY: Bradley shot the film with a specific point of view on the music. The camera would always be on the stage looking out. Except for one setup shot on an iPhone for use later in the film, there’s never an angle of any of the performances that would be as if you were an audience member seeing that performance. Everything was done from on-stage. That was definitely Bradley’s directorial decision, the way he wanted to see this world. The camera was on-stage with the Steadicam operator, Scott Sakamoto, and creating very long takes of the song. Like the last song — which is three minutes long — is really only three cuts.

The camera always stays with the performer. There were no cutaways to happy fans cheering them on. The audience was dealt with almost as a third person character. So the camerawork dictated that you were limited in what you were seeing. You were just going to see it this way, and that dictated how it would be cut. And, he didn’t shoot anything else to “protect” himself. It wasn’t like you had 18 cameras looking at an event. Bradley just didn’t shoot it. He took real risks in the photography. They had these huge crowds at Coachella and Stagecoach and he would shoot it with two cameras, both of them handheld on the stage and that’s it.

HULLFISH: That is not what I would have expected. I would have thought you had 20 cameras on every concert.

CASSIDY: There are about five big concert pieces in the film. The film opens with a concert piece which is completely onstage on Bradley and the camerawork is all handheld or on the Steadicam. And the crowd is just beyond and the lenses are fairly wide and so you see it all from this point of view of the performer’s visual memory of that concert. That’s the way Bradley was thinking of it.

CASSIDY: There are about five big concert pieces in the film. The film opens with a concert piece which is completely onstage on Bradley and the camerawork is all handheld or on the Steadicam. And the crowd is just beyond and the lenses are fairly wide and so you see it all from this point of view of the performer’s visual memory of that concert. That’s the way Bradley was thinking of it.

HULLFISH: I have incredible respect for the desire to do that.

CASSIDY: No coverage. Just intention. I started to work with Bradley when he starred in SILVER LININGS PLAYBOOK. On that film, he and David O. Russell began a very tight collaboration. And David, being the generous person that he is, wanted Bradley to come into the cutting room. Bradley — in his previous career as an actor — had been very interested in directing and been in and out of cutting rooms so he knew the process.

SILVER LININGS has a first act where Pat Solatano has just come out of the mental hospital and moves in with his parents but is still living the great delusion of getting back with his wife, Nikki.

So the question that David and Bradley had on the set of that movie was “how crazy was he when he comes out?” They decided to not commit during the photography and shot the whole first act with different pitches of craziness. And during the editing, we constructed different cuts with different levels of crazy because you had to build sympathy for this character, but you had to see his delusion, but if he was too crazy you’d just say, “well, forget it, send him back.”

It proved to be the right way to shoot and edit that movie. As well, the film benefited greatly by Bradley’s contributions to the storytelling, It was wonderful to see their mutual respect grow.

And then we continued on AMERICAN HUSTLE and JOY, David involved Bradley in much the same way. Even to the point when Bradley was acting in another film in Hawaii, he would join us for editing sessions via FaceTime – our longest was seven hours.

And then we continued on AMERICAN HUSTLE and JOY, David involved Bradley in much the same way. Even to the point when Bradley was acting in another film in Hawaii, he would join us for editing sessions via FaceTime – our longest was seven hours.

So that’s how I got to know Bradley and how our working relationship developed.

Because Stefani was not an actor, the studio needed to know if she could carry a movie, so in May of 2016, we did of a full test of a “sample” scene from the script at that point. We actually shot it at her house with a full crew and we edited it and re-recorded it here at Warner Bros. and made this little 15-minute movie which was a proof-of-concept for A STAR IS BORN. That triggered serious work for the film which began shooting in April of 2017. And during the month before beginning, I had the time and good fortune to work with Bradley as he did the final tweaks on the script. That study of the script was very valuable for me as we started making the movie.

HULLFISH: How long did principal photography go?

CASSIDY: It was nine weeks. It was all in L.A. or Palm Springs. We did one concert at The Forum in August which was a pre-scheduled event and we had edited up to that point, we knew where that concert was going to go and so we just sort of skipped through it and went on to other things so we probably had a month of editing after the assembly before we shot this last concert.

HULLFISH: You’ve worked with a lot of different directors. I’m personally working with a director right now who is also the principal actor in the movie. What is either the challenge or what is the benefit — or how is working with a director who is acting in his own film?

CASSIDY: Once Bradley finishes shooting — the guy up on the screen is somebody else. He’s able to disassociate the character from himself as a director very cleanly. In the cutting room when we were talking, we would always refer to “Jackson” or “Jack” — the character name — as opposed to “you”/Bradley. We kept that separation because we wanted to help reinforce the separation that he had to do. I think he was able to do it successfully and judge the material that he was in very critically and positively, He also would remember what he was doing in a particular take and he would know whether it was successful or not and he could articulate that.

HULLFISH: Did you approach musical scenes differently than the dialogue or other scenes that were in the movie? Or was it always your same approach the way you look at any scene: Here’s a scene. What do I do?

CASSIDY: For me, it’s just, “Here’s a scene. What do I do?” Each of the songs had a storytelling function. The Saturday Night Live song is a perfect example. Ally is singing a pop song. Jack is backstage watching it, and in the arc of the story, it’s his first view of the direction that she’s gone in as a performer; where the two of them are diverging on their particular paths.

A very important theme in this movie is that the Jackson Maine character wants her — the Ali character — to be true to herself and true to her voice; “having something to say and a way to say it so people want to hear it.” His only criticism of her is when he felt she was not being true to herself. She might argue that certain things that she was doing was true to herself and he just didn’t like it. That’s a central tension built into the movie and it’s different from the previous versions of A STAR IS BORN where the story dynamic was the ascent of the female star being born caused the descent of the established male star. In this movie, Jackson Maine, if he hadn’t met Ally, would have descended on his own. That’s part of the tragedy of the movie. His path was clear. Consequently, the scenes were always measured against where the two characters were in their particular arcs. Obviously, in the writing and in the structuring we knew where they had to be.

I suspect Bradley learned a lesson from David who will film exposition that also is covered in other scenes because he’s never sure just where he’s going to need to use that exposition. That storytelling flexibility proved to be a life-saver during AMERICAN HUSTLE. You could have had the plot reveal itself about six different places and that is David’s acquired wisdom because he’s made enough films to know that the script is simply an architectural blueprint. The support beam that goes across HERE, you actually need over THERE. So Bradley did a bit of that during shooting of A STAR IS BORN. We included them all in the assembly and pulled them out once the whole film was together.

HULLFISH: So when you’re cutting individual scenes, you’re leaving that stuff in?

CASSIDY: Absolutely. You’re cutting them long because of the way Bradley shot them— very similar to David who, as he works, is always considering several versions of the scene. So, like working with David, we never looked at a full assembly; there was no point, you had so many variations and sub-roads you could take, you couldn’t even tack it all together without it being enormous and really redundant.

HULLFISH: So how do you assemble a film in that case? You’ve just got to sit down with the director and make the decisions?

CASSIDY: You’ve got the scene and you’ve got a variation of the scene and you’ve got maybe another variation of the scene and then you and the director decide, “Let’s take THIS variation and use it.” David approaches editing as the last rewrite of the movie. I think Bradley approaches editing as the realization of what he does in the writing. And then look at it…

HULLFISH: You came on to the film during the script stage. What was your script involvement?

CASSIDY: Bradley — as an artist — always learns from taking the script or film, at whatever stage it’s in, and giving it to select people for their feedback. And so for me, in the few weeks going into it, I spent a lot of time with him basically giving feedback, but also listening to other people’s feedback that came in – certain producers, certain friends of his, that have been involved with the project and he was kind of percolating his way through it and then basically coming up with how he was going to shoot it. And so those were simply listening sessions and discussions. It helps me because I get to understand what the intention that he’s going for in a scene. What comes off the set may be different in terms of the way he worked out the script on the set. But the intentions are usually the same. So it was good for me because I really knew the material on a primal level of what we were trying to get at. And had seen many variations on the page and so when we started working it was very easy to make reference to things that were done in the script and why they changed on the set and whether an idea from the script was worth preserving or we could just dispense with it.

HULLFISH: And I bet even the producers and other people who offered bad ideas — that at least allowed you to start to filter your own perception of material when it came in.

CASSIDY: I should also say Bradley did the same process when he had a cut. He’d bring in people to screen it. Certain key people that he really trusted and had worked with on the script would see it several times — seven or eight times. When you do something and you bring in new people to see it, you see it through different eyes. The room changes and you learn so much about where your intentions succeeded, and how an audience reads what you’ve done. They may read it as you intended, or they may get skewed by a thought in a way that you hadn’t seen. So Bradley is a real big believer in that and we learned a tremendous amount from it and it gave us certain ideas for experiments — some good, some bad. There’s no question that we had tried every road with this material.

And the other thing I will say — because of schedule circumstances — we had the beautiful gift of time. We had a cut and we’d done previews and the studio’s happy, but you had a few extra weeks before we went into re-recording. So we ended up going right back to the original dailies and looking at takes we hadn’t used and why we had chosen what we had chosen. Often the choices were made very early. In two cases we re-cut entire scenes and the takes ended up being completely new for the whole scene. And we lived six months with the other takes. I look at those old takes and I think, “How could I have used those takes? These new ones are so much better. How come you didn’t pick those in the first place? It’s so obvious.”.

HULLFISH: And don’t you think that insight had so much to do with context?

CASSIDY: Oh, totally context! Also, the characters you had built had clarified. In one case, we took out one feature of the Jackson Main character — because we realized we couldn’t sustain it through the whole movie. But with some of the later scenes, we found artifacts of that. So we had to change them. All to the good of the movie. As a first film, I think Bradley is as happy as he possibly could be. I think he feels like we got the movie.

HULLFISH: Editing is a process. It’s not a one-and-done kind of thing. We’ve talked for almost two hours. Have we missed anything?

CASSIDY: We had the good fortune of having Stefan Sonnenfeld do the color-correction on this movie. He quickly understood Bradley and Matthew Labatique’s (the Director of Photography) choice of using primary colors as a storytelling tool. Also, this D.I. was my first look at Dolby Vision which is a beautiful format. The laser projectors are so much sharper than the previous generation of digital projectors. Bradley is enormously sensitive on a visual level as he as he is on a sonic level and that made the color-correction sessions wonderful.

HULLFISH: With his visual sensitivity, how were you monitoring in your cutting room?

CASSIDY: We had a 70” monitor and a projector as well and we could switch back and forth between them. But calibrated to rec709 as were the dailies. On the movie JOY, we went with P3 dailies instead of rec709, but we were not able to do that with these dailies. The thing that has been holding “P3 in the cutting room“ back is the monitors and now most of the good monitors have a P3 setting.

HULLFISH: What resolution are you using inside of Avid?

CASSIDY: On this film, we were at 1920×1080. I was really intrigued by your interview with Eddie Hamilton doing MISSION IMPOSSIBLE at the UHD resolution. The Media Composer can do the higher resolutions. Now the monitors are such that they can display the higher resolutions. It doesn’t take that much more storage, so why not?

HULLFISH: What do you think the discipline of editing on film taught you that you’ve brought into digital editing?

CASSIDY: It’s the old analogy of a typewriter and a word processor. Sometime around the middle of1994 was the first movie I cut with an Avid. After the first day, I was not going to go back. I had made my last splice. The Moviola was a great device and I used to use a flatbed and with a Moviola on the side. So you could have things broken down and look at them faster. Then I got the script tool inside of Avid and it was like the same thing I was doing on the Moviola and it’s a lot easier with the script tool. So I don’t look back. Whatever that discipline was wasn’t a discipline so much as a limitation – you could only do it the way you could do. I was an early adopter and continued adopter of the script tool. It got better this last year so I’m even happier. I’m one of those editors who invests a lot in preparing the script inside of Avid and barely opens a scene bin.

HULLFISH: Wow. Do you actually start cutting a scene from the script too or do you use a bin to start and go to the script tool later?

CASSIDY: I go to the script tool from the beginning. You can put the notes on the script. You can put a lot of annotation. You can use locators on the clips. If you have the script — even if it isn’t marked up right away — and you’re just doing the first assembly, it always makes sense to me to throw the clips on the script quickly as a way of thinking about the scene. The assistants prep my bins in Frame view (thumbnails) and I never use them. I would rather not rush to do the cut right away and really study the material. And that’s not a popular point of view, sometimes. But, on the other hand, there are times when you need to cut something really quickly to serve the production. We’d get the dailies in and by lunch we’d have a cut up on PIX so Bradley could look at it because he needed to see something for some reason. The time studying the material is so valuable that I really relish it.

HULLFISH: So when you’re studying the material I’m assuming that you don’t have the script integration completed. So you’re studying straight out of the bins?

CASSIDY: Most often the script is marked and ready. But in a rush, you take the clips and place them on the script so the clips are all linked to the script. Even if it’s not all marked you can add what you need right away… including the colors, if you want. It’s easier with the latest update to put annotations. So I just use the script as the place to begin to map things out. And then if it’s not fully marked, one of the crew can continue the marking of all the dialogue lines. But the clip is always linked to the script so that you can press the button and it opens the script up and boom there it is.

HULLFISH: For most people, it takes them so long to set up the script that the editor needs to do something else while that’s happening.

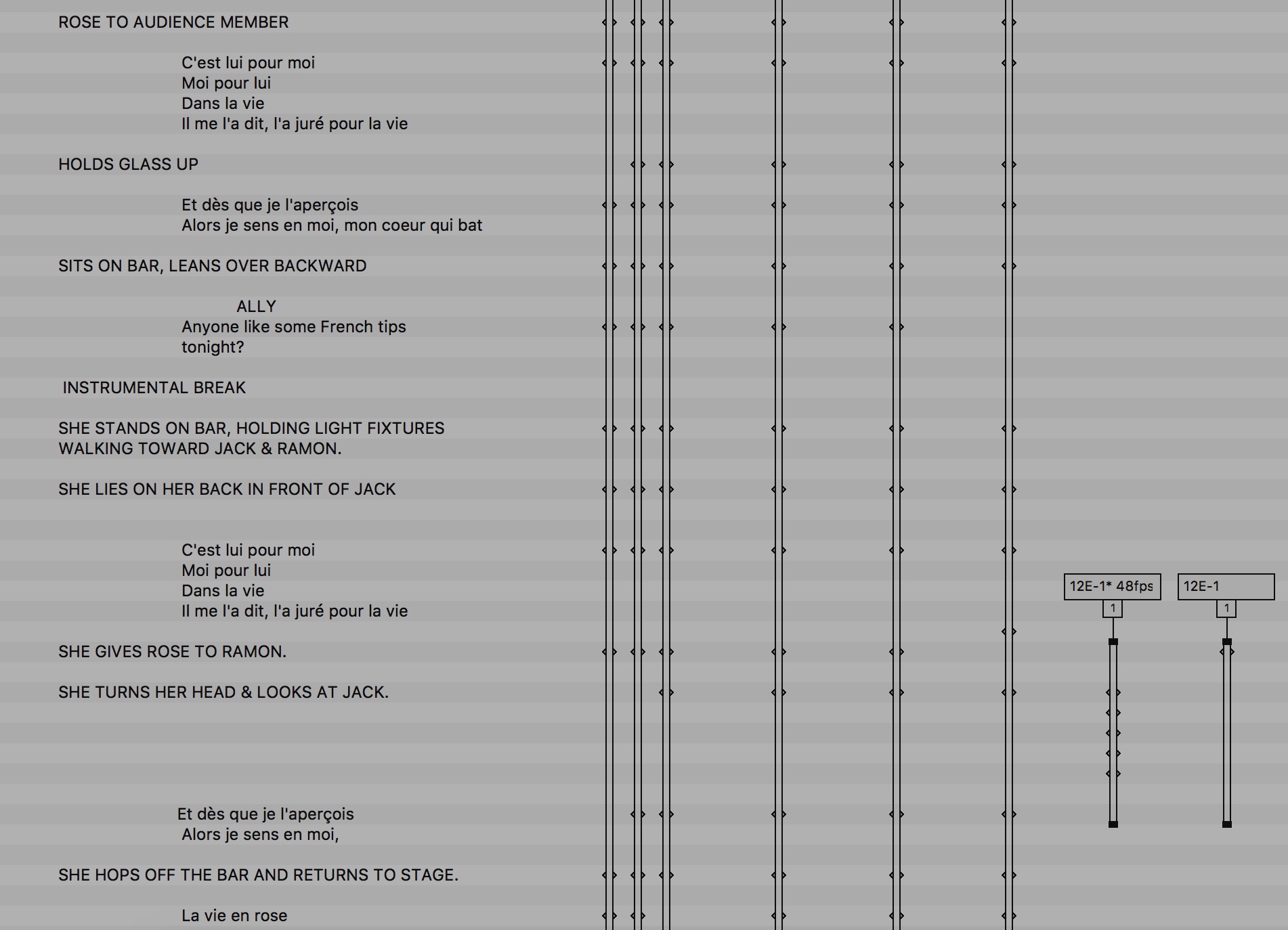

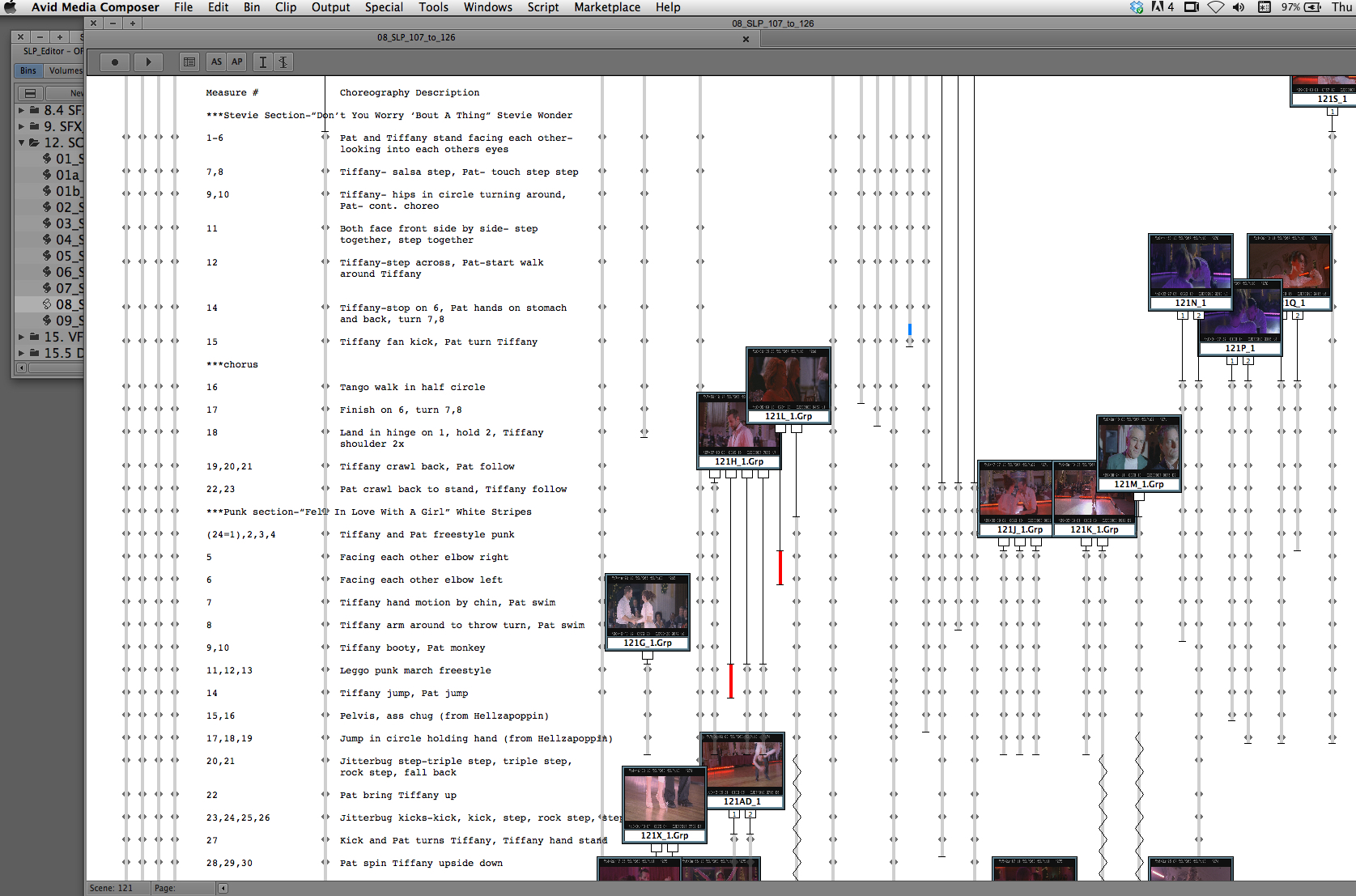

CASSIDY: Regarding adding description to the script, I can show you a script from SILVER LININGS PLAYBOOK that was really well-prepared. We had a member of the crew who was marking the script of the dance number and she had been a dancer. So we broke the dance down so carefully. She did it with such precision that it was very helpful. By adding the description of each dance move to the script, you can see, it contains marks on every beat of the choreography.

HULLFISH: Fascinating. So instead of using ScriptSync for dialogue, you create a detailed enough action description and then match the set-ups and takes to that?

CASSIDY: Yeah. We do that all the time. For action sequences, you break the beats down and type them out and paste them in and then use the script tool to go from kick number one to punch number two to kick number three. The script tool became a thing you could use in 1998. It didn’t change between then and two years ago.

HULLFISH: Do you remember what your first Avid movie was?

CASSIDY: The one I alluded to above. THE CROSSING GUARD with Jack Nicholson released in 1995. Shot on film. Cut it on film and then we were in the preview stage and there were some issues — especially with the way it opened. So we put the cut into the Avid to do some structural changes and then we said, “If we had the dailies in Avid, we could really do something,” so we had the assistants reassemble the film dailies, pulling the cut workprint apart and got the telecine done. That material was digitized and overcut onto the cut of the movie we’d originally loaded. So we backed our way into putting a whole chunk of that movie into the Avid. It helped us because it was a film with multiple stories intercut and the editing called for experimentation. You could do that on film of course. But you had to undo work in order to do the experiment, keeping a copy of the cut as a dupe. It would have been clumsy to do that experimenting on film, but it wasn’t clumsy in the Avid. I knew that I’d never go back to film.

HULLFISH: Thank you so much for hanging out with me and giving so much great insight into your process.

CASSIDY: Well, you’re the best place to yak in town. Your site is meat and potatoes. Here’s how people do it. If you’re going to take the time to read about a film, you don’t want to read about it at a superficial level. I’ve really enjoyed the interviews I’ve read and learned a lot.

HULLFISH: Wow. Thanks for that. Thanks for spending so much time with me.

HULLFISH: Wow. Thanks for that. Thanks for spending so much time with me.

CASSIDY: Thank you. Bye.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now