Feature film: first day. The crew and I start to run out of things to prepare; the director is 45 minutes late, despite the nervous producer’s assurances that he is on his way. Finally, the first-time director shows up: harried, stubbly, preoccupied and exhausted.

Blocking Before Coffee: the webinar

Stream it

on Moviola.com

He nearly stumbles to the ground in front of me as he thrusts out a rumpled stack of papers: “I finished the storyboards.”

I’ve seen this before. I want to hug the poor man. I want to turn to the crew and shout “it’s going to be a long day, boys and girls.” I want to explain to him, right then and there, everything that I’m about to explain to you in this article. But, instead, I simply say “Great. Let’s block the first scene.”

How to prepare to direct a movie

A movie’s design should start with a few guiding principles. This is true whether the movie is a feature film, a commercial or anything else that tells a story.

During the salad days of pre-production for this movie, we discussed the character arc of the protagonist: he starts out isolated by his fears, unable to connect with people. Forced to action by circumstance, he joins with his love interest, overcomes his fear, and changes his life. This movie’s themes, its guiding principles, were isolation vs. connection, danger yielding to safety.

A movie’s very specific and peculiar themes are the key to making the movie (Francis Coppola boils it down to one word; for The Godfather, it was succession). They are the basis for your production plan.

Storyboards can be helpful, as can shot lists, blocking diagrams and previz, in fleshing out your plan. Like directors, DPs do extensive script breakdowns to produce camera and lighting plans. They work with the Art Director to develop color schemes, sets, and so on. The very act of preparing these helps a director and DP think deeply about the scenes. Along

with production boards, wardrobe sketches, prop lists, etc., they help all departments plan and agree about the cinematic treatment of the story.

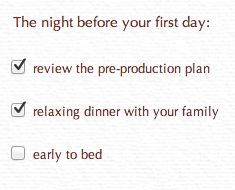

But let’s say the call time for a day’s shoot is 7 a.m. By 7:01 there is a problem for the director to solve. Despite visionary plans and good intentions in pre-production, the situation usually can’t be resolved by a storyboard or shot list or blocking diagram. The solution to most problems must be created immediately, on the spot, from almost nothing except the movie’s guiding principals plus the only suitable tool– creativity. Fatigue impairs creativity. Being creative while afraid is like sneezing with your eyes open– impossible. The production’s most vital asset is a prepared, calm, well rested, fearless and, most importantly, creative director. The pre-production documents themselves are a distant second.

The pencil, all powerful

Storyboards, shot lists and blocking diagrams are created on a couch with a pencil and paper (or iPad). All things are possible. Alone, perhaps, with his or her thoughts and unencumbered by the physical laws of the universe, the director is a capricious, omniscient god.

Creating movies, however, is another matter: there are other people involved. The earth turns, constantly moving both the sunlight and time. Rooms have actual walls. Lenses have physical properties. Neighbors have leaf blowers. Dialog is actually spoken, its meaning shaped by the actors.

Storyboards are great at describing graphic, 2D things: the bottle cap rolls across the counter, hits the soda bottle, spins and lands face up with the logo just so. Lovely. They are great for effects shots: this plate lines up with that plate. They are pretty good at describing most commercials, which must fit a few witty lines or iconic images into a preordained number of shots. These are all more graphic than narrative.

However, try storyboarding a dialog scene: you end up with lots of drawings of people’s faces, describing almost nothing of the human interaction that makes the scene work.

Bottom line: the more a scene is about humans, the less a storyboard helps. A shot list is essentially a storyboard for the drawing-impaired, except that it has even less ability to describe the human emotion of a scene.

Storyboards can be horribly misused on the set.

Storyboards can be horribly misused on the set.

- You can waste a lot of time trying, through brute force, to faithfully reproduce a frame in a storyboard which cannot be shot with actual lenses, people, movement or light.

- You can ignore the perfectly good, perhaps better, movie that is actually in front of you while making a mediocre replica of your storyboard.

- Storyboards encourage you to light and shoot a bunch of shots, laboriously, one at a time, that don’t necessarily cut together all that well.

A storyboard doesn’t have the capacity to contain a good story, anyway: like a screenplay, it is meant as a skeletal blueprint for a far richer movie.

By now, you may be objecting:

- but the Coen Brothers storyboard everything!

- how will I know what shots to shoot without a shot list?

- do you expect me to make the shots up, on the day of, under all of that pressure?

- all of the forums, all of the books, my film school– they all say that you have to storyboard!

Lets say, though, that you follow my strong, somewhat serious advice, and tear up your storyboards and shot list when you get to the set. How then will you have shots?

Block. Light. Rehearse. Shoot.

This method of film production has been practiced for 100 years:

1. Block

As the department heads watch silently, the actors and director walk through the scene, the actors acting their parts. Maybe he would stand farther instead of closer; her influence on him is stronger if she says this instead of that. He’ll look away evasively here and then look at her sternly here. The actors and director create what is actually going to happen; this could vary from the script or storyboard but is governed by the guiding principals in the pre-production plan.

Note: this is not the-director-acts-out-all-of-the-parts-and-then-asks-when-can-we-shoot. Unless the director is also the movie’s only actor, that is an expensive waste of time; it reveals nothing of how the actual actors will play the scene and answers almost none of the crew’s questions. Work proceeds at half-speed thereafter.

The DP notices, among other things, the glances of the actors: what are they showing and what are they hiding? Where are the performances directed? How does the set work with the story portrayed on it? Can the dolly grip really hit a tight mark like that? The blocking rehearsal makes obvious what shots to shoot, where there should there be light, shadow and movement, and how to

accomplish these things.

After the director and actors have finished the blocking rehearsal, and are nodding excitedly at each other, the DP suggests shots and lighting to the director: let’s shoot a master from here, lets let them walk out of the shadows to a closeup here, let’s be here with a 50mm lens to reveal his glance as he turns, etc. All of this is based on the drama of the scene just created.

The director may or may not buy these shots; they may work out other ones. Once they agree, the blocking, shot and lighting design is done: the actors and director go away for a calculated period of time. The actors get makeup, hair and wardrobe work.

2. Light

The electric and grip crews light the set. The other departments (camera, art, sound, and so on) prepare to shoot the scene.

3. Rehearse

At the appointed time, the director and actors come back for a camera rehearsal, which is essentially a final dress rehearsal. Small tweaks are made to the lighting, camera movement, etc. during this time.

4. Shoot

When everyone is ready, they shoot the shots. The script supervisor keeps track of what was shot at what angles and scales. The DP edits the movie in his or her head during the shooting. Between the two of them, they can assure the director at the end of the scene that all of the shots that they’d designed were shot.

[Repeat as necessary.]

The beauty of this is that all of the creative people work together, the sum greater than its parts, to create the movie. The scene is considered as a whole, governed by the characters and the story. The same lighting works for most of the shots. Everyone watching knows exactly what is going on. It is effective and efficient. Most of the best movies were made this way.

The correct answer to the question”what are we doing?” is “replacing you with someone who can watch a blocking rehearsal.”

When do we start?

Nothing much can happen on a movie set before a blocking rehearsal. There is no scene; none of the present creative problems have been solved; there are few obvious tasks to do before blocking. When should you begin blocking? At the call time. That’s right: the actors, the director and the crew should have the same call time and, after the safety meeting, they should immediately start blocking the first scene. All becomes clear: where to put the gear so that it is hidden from the camera, what makeup is required, which lights and grip gear to use, etc.

Most of the work before the blocking rehearsal is baseless speculation, a waste of time and money, a folly that destroys the shots that you consequently don’t have time to shoot later in the day.

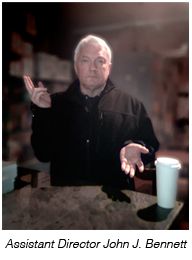

My icon for this method (in the Russian Orthodox sense) is Assistant Director John “Johnny” Bennett, who worked with me on a horror movie I shot called Red Ice. At the call time, John would gently (if possible) or firmly (if necessary) herd the crew away from the breakfast table to the set. Whimpering cries of “but I haven’t had my coffee” were met with a look that was like a two-second short film about pity, amusement, conspiratorial incredulity and perhaps the threat of impending violence.

My icon for this method (in the Russian Orthodox sense) is Assistant Director John “Johnny” Bennett, who worked with me on a horror movie I shot called Red Ice. At the call time, John would gently (if possible) or firmly (if necessary) herd the crew away from the breakfast table to the set. Whimpering cries of “but I haven’t had my coffee” were met with a look that was like a two-second short film about pity, amusement, conspiratorial incredulity and perhaps the threat of impending violence.

Storyboards, shot lists and diagrams are good at recording the essential design elements during pre-production. You can refer to these design documents, if you need to, before blocking to make sure you’re on track and haven’t forgotten a good idea. However, important elements of the scene can’t be known at the time of drawing a storyboard or making a shot list. Most of the co-creators of the movie, the actors, maybe the DP, not to mention the key grip, etc., are not present when these documents are made. These plans are therefore rather thin and lifeless.

Dissolve to: the harried and hapless first-time director clutching his storyboards. We make it through the first day. He is, however, unable to pay much attention to the blocking rehearsals, staring instead at the ‘boards. Same for the second day. Eventually, the questions from the actors and other practical concerns inflame his creativity and draw him away from his security blanket. By the end of the third day, the storyboards seldom appear on the set. And, for the first time, he is happy.

Don Starnes directs and photographs movies of all kinds and is based in Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area. He prefers to drink tea.

Also by Don Starnes:

![]() Monitors and filmmaking

Monitors and filmmaking

The difference between a movie and a video is that a movie is created in the filmmakers’ minds and a video is created on a monitor.

![]() Money

Money

It’s the Producer’s Invitational Pancake Breakfast. Just as the producers are cutting into short stacks with their plastic forks, all of the doors are locked…

![]() Ask me no questions and I’ll speak in no fragments

Ask me no questions and I’ll speak in no fragments

A sign taped to the door says “Quiet– filming.” This only makes you more nervous.

![]() How to get trained

How to get trained

Hint: it isn’t by reading this.

![]() Preview: the Mini XTC 9250-XL

Preview: the Mini XTC 9250-XL

Just in time for NAB, the 9250-XL is everything that a producer could want in a camera. The revolution has begun…

![]() DIY DCP

DIY DCP

How to make your own digital theatrical ‘print’ using Final Cut Pro, After Effects, guerrilla DCP software, pluck and maybe a little help from your friends.

![]() Keying and compositing in NukeX

Keying and compositing in NukeX

Skitch a ride up its steep learning curve using my template and tutorial.

G+

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now