.jpg) Gary Yost is a filmmaker and photographer living in the San Francisco Bay Area who focuses on telling stories about the interesting people and places where he lives. In a former life he was the leader of the team that created and then sold 3ds Max to Autodesk. See more from him on his website.

Gary Yost is a filmmaker and photographer living in the San Francisco Bay Area who focuses on telling stories about the interesting people and places where he lives. In a former life he was the leader of the team that created and then sold 3ds Max to Autodesk. See more from him on his website.

My idea for creating “The Invisible Peak” arose from a 2012 short film I made about what it’s like to be a fire lookout on top of the East Peak of Mt. Tamalpais, just 10 miles north of San Francisco. I created “A Day in the Life of a Fire Lookout” for fun and as a recruitment piece for the Marin County Fire Department, but it saw much wider distribution as a testimony to the beauty of our mountain and was seen by hundreds of thousands of people all over the world.

A Day in the Life of a Fire Lookout. from Gary Yost on Vimeo.

The Fire Lookout piece was so much fun to make that while contemplating my personal projects for the next year I decided to bring attention to another one of Mt. Tamalpais’ peaks. Tam’s West Peak (its actual summit) had been demolished and developed into an Air Force Station during the Cold War. When the government left the site abandoned in 1982 they just walked away and didn’t clean up after themselves. The junkyard they left up there included reinforced concrete foundations, asphalt roads, power poles, cables, transformers, and toxic asbestos.

I intended to raise awareness in our community about a place virtually no-one even knew existed because it’s been fenced off for decades. And as it turned out, the local water district which owns the land up there as part of our watershed has been trying to find a way to raise money for a restoration effort to return that area to a natural state. When I told them of my interest and how it aligned with theirs, a fantastic partnership was born.

This is a big story that stretches back 100 years… way beyond the scope of anything I’d done before. To tell it I had to bring in people and events in the history of the mountain to make it real. These include :

- Coastal Miwok Indians, who lived here for 5,000-10,000 years;

- Tamalpais Conservation Club founders, who protected the mountain and fought for the West Peak restoration;

- Army Corps of Engineers, who removed the top of the mountain;

- Military personnel, who lived at West Peak for 30 years;

- The Dalai Lama, who flew on a helicopter to West Peak in 1989 to perform a Lhasang blessing, which is an ancient Tibetan ceremony designed to create harmony between people and their environment, and which is always performed at the highest point on a mountain; and

- The custodians of Mt. Tamalpais at the Marin Municipal Water Department, who have been trying to find a way to fund the cleanup of the West Peak area.

The most important step in creating a film is to write what’s called a “treatment,” which is a prosaic telling of the story that provides clarity about the project’s intent. It’s a start-to-finish summary that takes what’s in the filmmaker’s mind and puts it on a page in black-and-white so that everyone involved in the project is conceptually together. I’d never written a treatment before but found that the process of doing it was clarifying and over the course of the project, as I edited drafts of the treatment, I’d refine my ideas and distill them down to the most-important issues. Here’s the full version of the treatment:

The Invisible Peak Treatment

I visualized the film being composed of major themes, woven into each other to provide a historical overview along with scenes from the area of the West Peak as it looks today. I wanted the narrative to drive the history, but to also bring in the poetic feelings that people in the area have about this mountain, considered sacred by many. Components I needed to create included:

- 3D reconstruction and animated visualization of the original topology of West Peak… something almost nobody alive has ever seen;

- Historical photographs of people on the original West Peak in the 1920s, in front of the WWI memorial cairn that was built there;

- Aerial/helicopter videography of the way the site looks today to put it in geographical context;

- Interview with a Coastal Miwok, speaking to indigenous issues specific to the mountain;

- Interview with elders from the Tamalpais Conservation Club who were involved in the citizen’s action work parties that began demolition of the barracks in 1985 and continued for 3 years before they were shut down due to asbestos exposure;

- Interviews with servicemen who were stationed on the Peak during the Cold War;

- 3D reconstruction and photographs of the Air Force Station taken during its operational period;

- Photographs of the Dalai Lama during his visit to West Peak; and

- Interview with a MMWD representative, explaining how the restoration project will work.

I’d never created a documentary before and finding a narrator who could bring the material to life was going to be critical. I’m lucky to live in the same town with actor and world-class narrator Peter Coyote and I reached out to him to see if he’d be interested in helping. Luckily for me Peter agreed to narrate the piece and help me develop the narrative arc for the film. I had no budget, was self-funding the project and he offered to do it for free. This is when things started to get interesting, and with Peter Coyote on board, the stakes were raised. I was heading into Ken Burns territory.

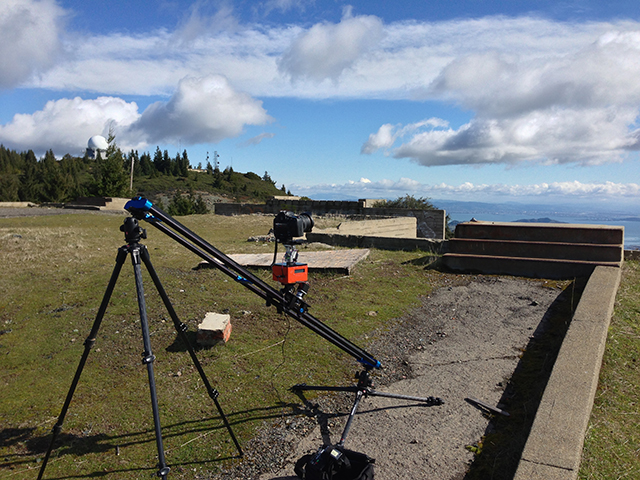

Shooting Time-lapse

I started shooting the dynamic time-lapse visuals in December 2012, with shots selected to inspire awe of the beauty of the place in poignant contrast with the decrepit and decaying foundations and detritus that the military left behind. My goal was to seamlessly integrate the time-lapse footage with real-time interviews, historical footage, and the 3D animation. Time-lapse films on the internet are usually 3-minute beautiful studies of a place with no narrative… eye-candy more than a real meal. I needed to find a way to use the medium to drive a complex story forward and to give viewers a visceral sense of the place and history. I’d seen this done in Jeff Orlowski’s amazing film “Chasing Ice” about climate change and knew it was possible.

With time-lapse, weather is always an issue because you need interesting moving clouds to convey the passage of time. Unfortunately the 2012-2013 winter was the driest in San Francisco’s history and I had to become an amateur meteorologist to stay on top of the few days that presented good shooting opportunities. I primarily us the NOAA weather forecasting tools, starting with their excellent forecast discussion. And of course the invaluable mobile app “The Photographer’s Ephemeris” kept me in touch with exactly where the sun and moon would be every day.

The water district didn’t have any funding for me, but they did give me an all-access permit and a key to the locked gates. Since this area is only 30 minutes from my home I was able to drive up there frequently – only to be disappointed many times by the lack of reasonable shooting weather. But perseverance furthers and within 6 months I had accumulated 5Tb of source raw files, compiled into hundreds of different shots of the area. The gear was completely bulletproof and I was able to set up both rigs within 30 minutes of arriving on scene.

My workflow for the time-lapse sequences was to bring all the raw files into both Lightroom and LR Timelapse. Using LR Timelapse’s powerful RAW keyframing functions I carefully extracted all possible information from the image sequences and then rendered those out to ProResHQ movie files.

My time-lapse kit included two slider-based rigs:

- Nikon D4 w/14-24mm lens, on Kessler 2’ PB slider (1 axis of motion)

- Nikon D800 w/16-35mm lens on Dynamic Perceptions 6’ Stage One slider and eMotimo TB3 multi-axis head (3 axes of motion)

Once they were brought into FCPX, I was able to use the retiming functions and optical flow to control the pace of the time-lapse sequences. Here’s a screenshot of the timeline during the “this is what halfway to restoration looks like” montage at the beginning of the second act of the film.

Shooting interviews

The interviews were a different story and quite a bit more challenging. I’d never done formal interviews before and, after a horrible failed test shooting an interview on site at the Station in a very unflattering way, I decided to take the Ken Burns approach and use controlled lighting and tight closeups to provide a consistent look to the piece (and make my job more manageable). I was a one-man band and managed all 9 of the interviews, handling lighting, sound, camera op and interviewer roles simultaneously by myself. This was overwhelming but since my budget didn’t allow for a crew, I had no other options. As you can see, it worked.

My interview kit:

Nikon D800 w/85mm lens, Rode NTG2, Juicedlink pre-amp, Westcott Ice Lights

Shooting Aerials

The aerial shoots were the biggest challenge because I’d never done any aerial cinematography before. After doing some research on gyro stabilization I rented a ATM X8 gyro from a local supplier and the folks at SF Helicopter graciously took the door off one of their Jet Rangers for me. After getting over the nervousness of hanging onto the outside of helicopter and doing a few tests on the early part of the flight I got the hang of it and had a very successful (and super fun) aerial shoot.

BTS shooting DSLR from Bell Jet Ranger 407 from Gary Yost on Vimeo.

In order to show the pilot a visualization of the flight route, I made a Google Earth animation and sent it to him in advance.

We modified the flight plan slightly, and you can see a full set of rushes from the shoot here:

3D Animation

I filed three Freedom of Information Act requests to get images or film of the Army Corp of Engineer’s excavation of the mountaintop in 1950 but was denied. Having footage of the mountaintop removal was critical to getting viewers to understand what had happened up there, so my only alternative was to build the entire scene in 3D as a simulated re-creation. As the developer of 3ds Max for Autodesk I’m used to doing large-scale 3D projects and brought in my friend Jamie Clay to work with a 3Gig dataset of the entire mountain that was given to us by the water district. Jamie was able to massage the data into a usable working model and then, based on pre-excavation topographic maps he rebuilt the original mountaintop along with all 28 of the Air Force Station buildings, plus roads, powerlines and infrastructure.

To give the 3D footage an authentic old-film look I used Red Giant Retrograde’s 16mm Aged Film plugin, along with FCPX’s built-in Crop & Feather effect. This gave me exactly the style I was looking for and also used Retrograde on some of the historical still images to match the overall look.

Historical footage

Let’s face it… a historical film needs historical footage. After googling around the internet I came across the most incredible library of archived historical footage, the Prelinger Archive. Rick Prelinger is an archivist who partnered with the Internet Archive to make over 6,000 films from his archive available freely, with a Creative Commons Public Domain License, to anyone. No permission needed!

When I was first researching how to find archival footage, my search terms led me to this film in the Prelinger Archives about the Mill Valley Air Force Station from the mid '50s.

Finding that film was like a HUGE kick in the pants. And as it turns out, it's the only newsreel the government ever made about a radar station. How lucky is that? Kismet!

And when I needed to find footage of the station in operation, and the military refused to honor any of my multiple Freedom of Information Act requests, I did more digging and found some footage of the Station that a 1956 Republican Convention delegate in San Francisco took on a side trip to Marin.

Kismet again!

This led me deeper and deeper into the project, and I was able to complete my historical vision using various Cold War films on the site.

The Big Picture: https://vimeo.com/75647759

Atomic Alert: https://vimeo.com/75338522

Duck & Cover: https://vimeo.com/75338382

The historical footage, even though it was low-resolution, came seamlessly into the edit and was a joy to work with. All it usually needed was a little finessing in the color board for contrast.

Photogrammetry

I was lucky to find a set of B&W images in the Library of Congress archives that were taken of the Air Force Station soon after it was decommissioned in 1982. I wanted to create composites of these images overlayed with time-lapse sequences of what the buildings foundations look like now, but the originals were shot on a 4×5 camera with an unknown lens. Creating perfectly-registered composites was going to be very tricky, but I developed a technique for doing this by bringing the b&w images into my Zacuto EVF’s frame store, setting the transparency to 50% and overlaying the historical b&w photo on the camera frame with a 28-70mm zoom lens, playing with the distance from the subject and the focal length until I got as close a match as possible. After rendering those time-lapse sequences I sent them to Jamie and he warped the original stills just enough to achieve perfect registration.

Photogrammetry time-lapse composites of the Mill Valley Air Force Station from Gary Yost on Vimeo

The Edit

After 6 months of shooting and acquisition of assets, I began the edit phase. I’d been using my old 2008 Mac Pro but it was slowing me down, so I sold that and bought a BTO iMac with 32G, along with a Promise Pegasus R6. The new system gave me all the edit power I needed! It was a gas to see how well Final Cut Pro X could actually run on a modern machine. (I had no idea how crippled I had been by the old Mac Pro.) I’m a big believer in collaborative synergy, and so in July I asked my music supervisor George Daly to help me with the entire post-production phase… to co-direct, co-write and co-edit the film. George was enthusiastic about the project and we started doing sessions together every other day. Each edit session was also a script-writing session and we’d spend 3-4 hours each session on constructing a small piece of the program. After George would leave I’d continue finessing the edit and script and we’d then show it to Peter Coyote, who’d further edit it based on his sensibilities. This continued for 3 months until we had a first rough cut, and then we brought Peter into the studio and recorded the final narration.

My co-scriptwriters… George Daly and Peter Coyote and me.

Once we had the narration done, plus a locked edit, George was able to start on the music and sound effects. He brought in two composers to write the score; Michael Hoppé and Ron Alan Cohen. They began working on the music and George focused on the sound effects, and by early December we had an emotionally-powerful soundtrack! I’d always been a firm believer that the soundtrack for a film is even more important than the visuals because you can close your eyes and still enjoy a film, but turn down the sound and it gets boring real fast.

George then did audio sweetening on all of the interviews, which had been recorded straight to the D800’s h.264 file with the Juicelink Riggy Micro preamp and a Rode NTG-2 microphone. And finally he sweetened the narration, mostly to remove any residual plosives and add some ambience.

While George was finishing the soundtrack, I went through a long process of visual-cleanup and grading. When shooting time-lapse in nature one of the gotchas is birds. They fly in and out of the frame and that appears as annoying intermittent black specks in the rendered sequence. (In this case most of the birds in frame were crows and ravens.) I had to go into dozens of shots and hand-paint birds out using the healing brush in Lightroom, which was easier than it used to be before LR5’s introduction of the healing brush. Still, that took weeks and then I was finally able to start doing color grading, which I mostly accomplished in the FCPX color board (an excellent basic tool) along with a few plug-ins like Hawaiiki Color and the Noise Industries White Balancer. I brought in Dan DiPaola who’d done colorist work for the Walt Disney Company as a consultant near the end and he helped me optimize a few of the shots I was having trouble with. And here’s the timeline of the entire show as it was finished. Our final edit has more than 800 elements in it, based on 1263 clips in the Event library.

Once I created the release version of the 22-minute film, rendered to Bluray, I started submitting to film festivals and have already been accepted by the Tiburon Int’l Film Festival, the Sacramento Int’l Film Festival, and we hope to be selected by a few more of our Northern California regional festivals this year. We had a sold-out standing-room-only premier at a local theater, hosted by Peter Coyote and sponsored by the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy with live music… a very fun and exciting evening.

The future: My intention is to continue to document the Parks Conservancy’s fundraising activities for the restoration and then to film the restoration itself. In 5-7 years I ought to have a feature-length doc about how a community can come together and support a large-scale restoration project like this. Being able to film it as it happens (compared to looking for historical footage) will be a tremendous benefit! While in production on that I'm going to be making short films about the West Peak area to keep the public informed of what's going on. Here's the first one of those, about a beautiful forest that has been fenced off by the military for the past 72 years but will be reopened as part of the restoration very soon.

Hidden West Peak Forest from Gary Yost on Vimeo.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now