Elisabet Ronaldsdottir was born and raised in Reykjavik, Iceland and has been editing film at home and across Europe and America since the days of editing on celluloid. Her films include Contraband, The Deep, John Wick, and her latest work with director David Leitch on the film Atomic Blonde. She has won several Edda Awards for Best Editing in Iceland and has been an active member of Iceland’s film industry guilds and academies. Art of the Cut interviewed her while she worked on Deadpool 2 in Vancouver.

HULLFISH: So you are working on Deadpool 2

RONALDSDOTTIR: We’re shooting now. It’s fun. Fun but a lot of work. The best part is being back with the clan that was also behind John Wick and Atomic Blonde: Director David Leitch, Producer Kelly McCormick, Director of Photography Jonathan Sela and my Assistant Editor Matt Absher.

HULLFISH: What was the schedule for Atomic Blonde?

RONALDSDOTTIR: We started principal photography in Budapest. I think it was beginning of November 2015. I arrived in Budapest maybe two weeks before and we were shooting in Budapest until February. Then we moved from Budapest to L.A., where we offlined the project. We did the finishing work in Stockholm with a company called Chimney Pot. So we did the color grade, graphics and some sound pre-mix in Sweden. Chimney in Berlin did all the visual effects.

HULLFISH: So you’ve done a bunch of these very high action films like John Wick and Atomic Blonde and now Deadpool 2. Let’s talk about the challenges of editing these highly choreographed stunts and working with stunt people that you have to then hide.

RONALDSDOTTIR: I’m pampered because I’ve been working with some of the best stunt choreographers and directors. So for me, it’s easy. I find it so easy to edit well-choreographed action. But then again, I come from a dance background and I’ve made many dance films. So I understand the basics of dance choreography – and action is kind of the same thing.

What I don’t understand is the idea that post should hijack the film once it’s shot. You have amazing professionals, for example, the stunt choreographers, doing magic and you need to talk to them, involve them directly in the editing dialogue during the cut. This is what we did with both John Wick and Atomic Blonde — we get the stunt choreographer and we have a discussion. Because you have to think of so many things. It’s not just the stunt itself. It’s also how it flows with the rest of the film, how it peaks or ebbs, etc. So it’s important to have this discussion and maybe the person involved can point out a better take where the stunt has a cleaner movement or something else. I remember on John Wick, the stunt choreographer pointing out to me, “He needs to put his foot behind him like this,” because that’s a very specific move in judo and I had cut it out. But then we discuss, “Sure, the action is better in this take, but we don’t see this person in the back as well.” And then we find the middle ground that works best for the film. On Atomic Blonde we have this bad ass sequence that runs for almost 12 min. meant to look like a one take. For that, I was editing on set to make sure we got a cut that worked but also to try to assist in not losing sight of keeping the story strong – “can we pan a bit over to this guy so we don’t lose track of him” but most of the time I was just sitting there mesmerized over Charlize, she is amazing.

HULLFISH: With choreography in film it’s about showing the whole body, right? Yet, with someone like Charlize who is so beautiful you probably think, “Oh let’s be on her face” but you can’t do a fight scene on Charlize’s face because you’ve got to see the motion.

RONALDSDOTTIR: David Leitch is a director that understands the importance of emotion in action sequences. In John Wick, we were on his face a lot because it was an emotional ride. We had to see that he didn’t want to do what he was doing but that he was really good at it and respectful of his opponents and the art of defeating them. Also in Atomic Blonde, the fight sequences are such an important part of Charlize Theron’s character’s emotional journey, and so we always made sure to follow up fights with a close up, but of course it would never work without an actor that has an amazing connection with the audience through the lens, and both Charlize and Keanu have that. The one thing that is similar with both movies is that they have very tall main characters doing the fighting and there’s something about the aesthetics of that that changes everything. It’s very different to see tall people fight. You get bigger movements of the body: legs fly higher. A great example of that is the silhouetted fight scene in Atomic Blonde behind the screen in the East German movie theater. I think it’s stunning. I think it’s beautiful.

HULLFISH: Do you have a process for watching dailies?

RONALDSDOTTIR: I go through the dailies. I throw them together very roughly. Just to make sure that we have the scene covered. For me, I keep the story clear in my head by reading through the script several times. I also look at all the source material that is made before principal shooting, storyboards, vfx vis and even stunt pre-viz. It is very helpful because it helps identify what the director is looking for in the scenes.

I like to be involved at the end of the script process too, I need to discuss my notes before we shoot – even though no one listens to me, at least I got a chance to say it. (laughs). There are so many rewrites of those scripts and sometimes there are ghosts hanging around in the script. Those ghosts are a part of the process, but being new to the script it’s easier to spot the ghosts and point them out. The story is the most important part of the editing process for me. No matter how fun the action sequences are, it’s the story and the character arc that stand out. I have a great respect for what the audience brings to the theater: their brains. So I don’t think we should be force-feeding the audience. But you try not to leave too many gaps, so they don’t have to take too much of a leap to follow the story.

HULLFISH: You mentioned “ghosts” in the script and for those that might not understand that, I think I know what you’re talking about. I had the same issue in the last film that I cut. There were so many versions of the script done before I came on board and then I got the script and I was lost about certain things. When I asked about certain plot points the producers said, “Oh, that’s because this happened and this happened in previous versions of the script.” And I had to point out: that’s not in the script anymore. So there are these “ghosts” of previous script versions that can affect the story in negative ways. They’re the thing that people on the development side of the movie remember happening but they no longer happen because they’ve been taken out of the script in the revision process and those can be huge problems right?

RONALDSDOTTIR: Yes exactly. And that’s why it’s important to get someone that’s not involved in the script writing to come in and be more objective.

HULLFISH: I want to be much more granular in our discussion of how you watch dailies. Do you watch last take to first? Do you take notes? Do you start building selects reels immediately?

RONALDSDOTTIR: Back in the day, we would sit in the cinema and just watch dailies and discuss them. Now we don’t do that. We try once or twice, during principal photography, to watch dailies together, but it’s hard to find the time in everyone’s busy schedule and those who need to watch dailies do it either online or get them delivered on an iPad.

I’ve been in this business for a long time. I started editing on film: a Steenbeck with a splicer and the white gloves. Then they shipped all the Steenbecks away and brought in the computer. Suddenly the producers thought that would cut post production time in half, but nothing up here (she points to her head) is going any faster. Plus, with the computer, it’s so easy to make different versions and test out things that you couldn’t really do with film. So you’re actually expanding the post-production time because it just takes more time when you have so many options and can try out so many different things.

Sometimes I’m watching the dailies as they arrive and all of a sudden, I’m halfway through editing the scene because something I saw leads to a great idea and I just have to try it. It doesn’t mean I don’t look at all the dailies at some point, to find the best takes or dialogue, I do. I become very familiar with every take at some point, just not always the day they arrive.

HULLFISH: I heard a great quote this week from Carol Littleton: “You can’t know in week two what you know in week ten.”

RONALDSDOTTIR: A great quote. Yes absolutely. I’m not stuck in my ways in that sense. Sometimes I look at the rushes that just arrived but I’ll go and edit something from last week because today’s rushes gave me a better insight for that particular scene.

HULLFISH: How do your assistants set up your bins?

RONALDSDOTTIR: Matt Absher has worked with me forever and he builds the foundation for us to work on. He generally keeps the bins structured by scene order in Frame View, but sometimes you will have a massive action sequence that they shoot in pieces and it gets more complicated, so we divide them up by blocking. And then I have my lined script and so it makes it less overwhelming as the shot ratio gets higher.

HULLFISH: Since switching to film have you always been on Avid?

RONALDSDOTTIR: I’ve done everything, I think. I can’t even remember the name of the first software with the door and the fish?

HULLFISH: Maybe Lightworks? That’s the one Thelma’s Schoonmaker uses.

RONALDSDOTTIR: Lightworks! She does? Maybe I should have stuck with that… (laughs). I’m not a technical editor. I’ll cut on anything. I’ve worked on FCP7, which I liked a lot before they changed it to FCP-X and I’ve edited on Premiere. If you give me scissors and glue, I’ll do it with that. But if you’re going to hand me a computer it better be a fast computer because my ideas flow quickly. (laughs)

HULLFISH: If you liked FCP7, you should check out Resolve.

RONALDSDOTTIR: Really? I’m open to anything.

HULLFISH: So was Atomic Blonde cut on Avid?

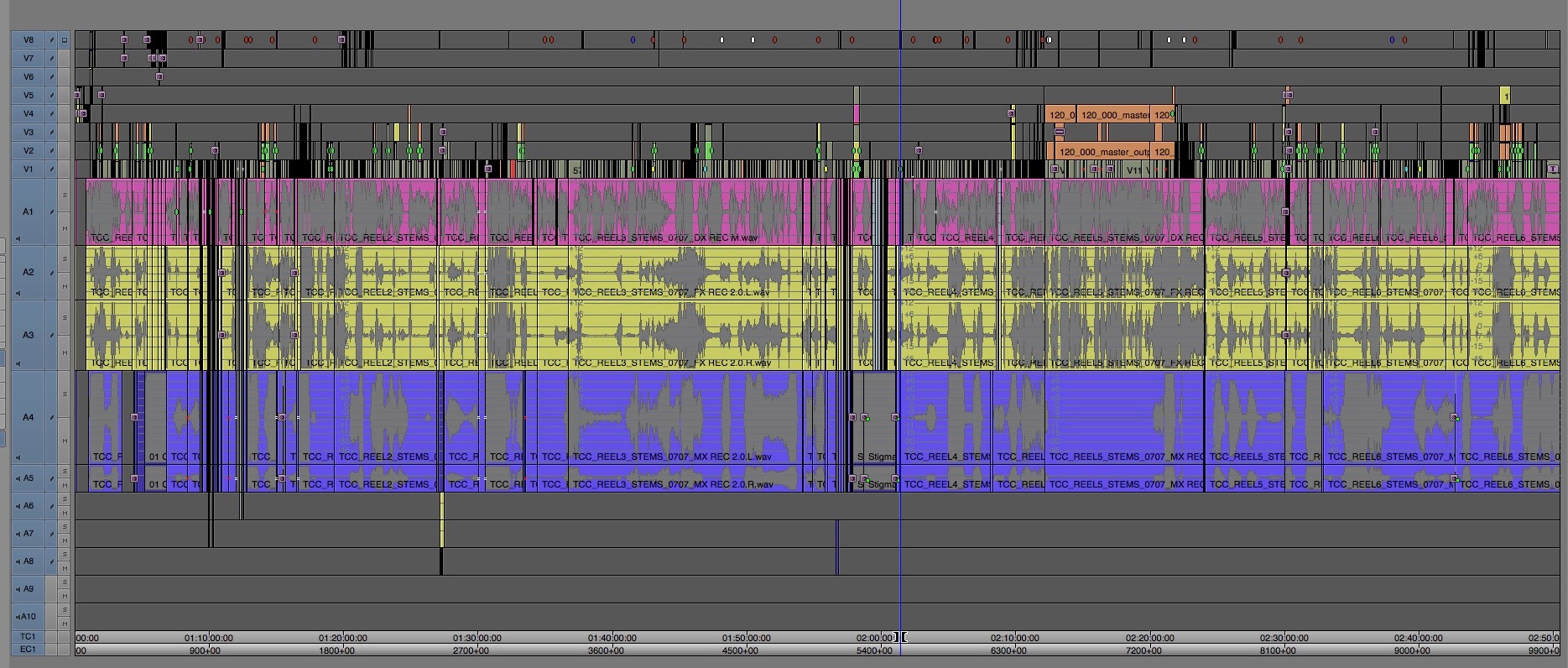

RONALDSDOTTIR: Yes. Avid.

HULLFISH: So, you’re cutting Deadpool 2 now. What about that? The first one was cut on Premiere.

RONALDSDOTTIR: We’re back on Avid. We have a very condensed post schedule and with great respect to all other soft- and hardware, we felt Avid had the most solid pipelines already in place, and can easily handle the amount of data we will be receiving. The whole team is accustomed to that system.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about temp music.

RONALDSDOTTIR: Well I try to be very careful because you don’t want people or yourself to fall in love with something that’s not going to be used. I never ever edit to music. Never ever. I think it’s so important to find the music and the rhythms within the scene itself. I listen to a lot of music, even as I´m editing but I don’t cut to the music. For me, it’s very important to be able to watch an edit without any music. Maybe it’s just my overblown ego, but I really believe there is music in the editing and if you can get the rhythm right, you can put any good music on it and it will work. I’m excited to use music that isn’t necessarily on the same emotional level as what’s happening in the scene, not in the same tone, I don’t like to layer-cake the emotion, and to me, it actually feels more emotional to contrast the emotions on the screen. But now I know I’m generalizing too much and might even sometimes completely disagree with myself.

HULLFISH: So were there a lot of 80s pieces of music in the Atomic Blonde that had been pre-selected for specific scenes?

RONALDSDOTTIR: Absolutely, David was very specific about what he wanted and had researched it for a long time. I believe the playlist he made for the film was his first introduction to the project to me, along with the comic book. Almost every track made it into the soundtrack even though some got moved to other scenes than originally planned. David even shot some scenes to playback of the music he had chosen. And even then, we watched the scenes dry without music to make sure they were emotional and impactful without the music.

HULLFISH: When you’re cutting action, do you find that you have to personally put in a lot of sound effects to get the rhythm right?

RONALDSDOTTIR: I do use a lot of sound effects, Matt always takes a pass after the first rough cut of a scene, but all those gunshots and hits do affect the rhythm immensely.

HULLFISH: One of the things that you talked about was the emotion of some of these action scenes INSIDE the action scene but you also need to have that emotional connection BEFORE we get to an action scene so that we have an emotional connection to a character, right?

RONALDSDOTTIR: Do we? Well, it’s very popular in films to start with a blast of action. And why would you not be able to emotionally connect with a character through a fight scene? But yes, at some point you want to be emotionally connected to the person that you’re looking at. Atomic Blonde is such a different film from anything else that I’ve participated in. And it’s especially a different film from John Wick. John Wick is a simple revenge story, like the Nordic Sagas. Some one slaps you in the face and 300 people have to die and no one questions the revenge. “You killed my dog. I’m going to kill all of you.” Emotionally we can relate to the anger and frustration over something that has been taken away from you.

Atomic Blonde is so different. If we are talking about it on an emotional level, it’s about people who build walls because they have so much to hide, there are just too many secrets, and they’re each so compromised. They can’t talk because the truth might slip out, and the truth will not only put them in danger but anyone close to them, so they become disconnected. That’s what this film, in my mind, is about and that’s what made it so complicated to edit. Lorraine, Charlize Theron’s character, tells us the story of what unfolded in Berlin late 1989 from her perspective, the week leading up to the fall of the Berlin Wall. It’s not a revenge story. It’s not a who-did-it story. It’s more of a journey. You are told a story and then things turn out to be more complicated than we are told to begin with. So the story itself is very complicated and we put a lot of work into trying to make it so people could enjoy it on different levels. So if you like a complicated spy movie, with twists and turns, you should be fine. If you don’t like that and you just want to see beautiful people and beautifully shot action, you should be fine. Do you need to emotionally connect to a character? Yes. But emotions are complicated and how you connect is complicated and how we feel entering the theatre matters and affects our ability to connect just as much as anything else. I’ve watched a movie and almost peed myself laughing and then saw it less than a year later thinking – what in the world did I find so funny? What made my journey with Atomic Blonde — which we always knew as The Coldest City — but they changed the name recently, was trying to balance that we were working with a character that is keeping you at a distance the whole time, for a good reason, and our need as audience to connect emotionally with that character.

HULLFISH: There’s the text of the story, then there’s the subtext. Are you trying to keep that subtext in mind as you are choosing performances?

RONALDSDOTTIR: Absolutely! That’s extremely important. Yes. That’s part of the work we do. In Atomic Blonde there’s a lot of subtext about the useless political games played and how they affect people – a lot of references to the game and how we are gaslighted even when the poles are shifting, and lives are changing. To make that point, and to help with the conclusion, we moved Percival’s monologue towards the end: “what was it all about, who won?” instead of having it opening the film as it was scripted. We also combined different scenes to add to Lorraine’s dialogue: “My superior? You just didn’t want your dirty little secrets out” – and moved it closer to the end of the final interrogation scene, plus added some ADR here and there, for various characters, in the hopes of punctuating that specific point. We worked on making the TV a character that tells us the story of the wall coming down, we wrote the news anchor’s dialogue in the editing room, based on real news and we had an actor come in to read it, and we closed the TV character with MTV: “hey, that wall coming down is cool and all but let’s talk sampling, is it art or plagiarism.” I hope people will be able to enjoy Atomic Blonde on lots of levels. The level as a spy thriller and of the internal struggle of people who are living dangerously and lying to everyone: family and friends; or to enjoy it simply as a beautiful rock-n-roll action 80’s style musicvideo.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about making story decisions; because I’m sure there were things that had been over-explained in the script then you had to determine where and when you have to let the audience use their brain, and when do you have to make sure the audience absolutely gets this or else nothing else makes sense.

RONALDSDOTTIR: Yeah. And that was difficult to find that line on this film because some people are extremely cinema-savvy and then you have to respect that most people aren’t, and it’s a fine line. We, at one point, deconstructed the whole story, the dialogue part that happens in the interrogation, and then put it together again where we tried to keep the threat, we deemed important, steady through the whole story. There are very, very few scenes that we cut completely out but we shortened most of them a lot, but don’t worry – we didn’t shorten the action.

HULLFISH: I want to discuss a little bit more about balancing the story. What were the discussions or what did you sense before you balanced it? What did you sense the problem was? I’ve been on films where you say, “it’s too long before we introduce this character the way it is now, so how can we get this character earlier?” What were the discussions on Atomic Blonde?

RONALDSDOTTIR: This film has very important information coming through dialogue. It’s not a linear film. And we did play a lot with that, in order to get a better control of the story. We even went non-linear within the linear parts of it. Crazy fun. It was very important to get certain information in the beginning as it is crucial for the end twist to work, but we still didn’t want to drown people in dialogue and force feed all the clues.

One of the big problems of the film is what makes it particularly special, which is everyone is lying. So how to reveal all the lies and when was a unique challenge. Our central character, Lorraine, is telling us her story and she is an unreliable protagonist. We see everything from her point of view and then it kind of switches towards the end. Also, some energy went into building up the antagonists, in the form of C and Gray played by James Faulkner and Toby Jones. We did some work on Percival’s arc, who is played by James McAvoy, so we could root for Lorraine. One of the beauties about this film is that no one is really good or bad, they just all have some major issues.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk a little bit about performance and what makes you feel like this is a great performance. Then also, how are you forced, even with a great performance to mold or shape it to be what needs to be?

RONALDSDOTTIR: Great performances are great performances.

I don’t feel like I’m molding great performances. It’s how you let them shine, without over-cutting everything, especially the main character. You have a main character and that’s the one that should let shine and when you have supporting actors, you don’t really want or need them to shine brighter.

HULLFISH: I was more thinking of the temperature of the performance because you can have a great performance that is very strong and could be correct for a story. But then when you look at it in the context of the overall film you decide that you need to use different takes because some other editing has changed the arc of the character from where it was in the script.

RONALDSDOTTIR: Yeah. Absolutely, and we do a lot of that. Sometimes we also have to adjust using ADR, if we don’t have the means for additional photography or pick-ups.

HULLFISH: My thing that I’ve discussed with so many editors is that you don’t need to wait for the notes after a screening, Right? All you need to do is sit in a room with an audience.

RONALDSDOTTIR: Yes, you sense it and that’s very important. Both David (director, David Leitch) and Kelly (producer Kelly McCormick) and I turned up for every single test screening to feel the room. Test screenings have become a thing of their own. There are people that look out for those test screenings and they want to be there. It has become their thing and they are writing whole essays on how to make those films better. I don’t want to be rude or aggressive but I think it’s a double-edged sword. Because people feel like they should say something because they’re there for a reason. So, they start digging and pointing out stuff they would never have thought of if they saw the film on their own. Then there’s the “professional” test screening audience and I understand their interest in it, but it’s very tough perhaps how to deal with those notes. I have great respect for those notes, but…

HULLFISH: …but that’s why it’s better to just be there in the screening right? Not so much for the notes but the overall reaction.

RONALDSDOTTIR: Absolutely. And I always go out and stand in the door when everyone walks out so I can listen to what they’re talking about.

HULLFISH: What is your method of collaboration and does it have to change from director to director?

RONALDSDOTTIR: Yeah, it does change from one director to another in the sense that I’m a bit of a chameleon. It’s very important to me to listen to the director – what their words are, what their vision is, and I try to visualize what they are seeing.

I’ve been extremely lucky and I’m always learning, which I love. The day I stop learning something in this job is the day I need to go and do something else. I’ve been able to collaborate with some great directors in Iceland as well as in America. And in the future, I would love to work with more female directors.

HULLFISH: I just did interviews with the editors for Kathryn Bigelow (Detroit) and Patty Jenkins (Wonder Woman).

RONALDSDOTTIR: I just think it’s important for all of us as an audience to have as many voices and as broad a vision as possible. Not always men. And I have nothing against men. Some of my best friends are men (she winks), but the more women the merrier.

HULLFISH: That’s my motto! Let’s talk some more about the social aspect of editing and discuss the balance between having a very strong ego, because you said that you have a very strong ego and yet you know that you have to subvert that ego to the director’s vision but also to provide the director with enough of your own vision that you are valued.

RONALDSDOTTIR: I think this is like any communication with anyone in your whole life. Film is a bunch of massive egoists coming together and trying to figure it out. It’s not only the actors. We’re all massive prima donnas and crazy people. I mean that’s what we love about this movie business anyway. I think it’s important to talk, and I would never just let something pass. Let’s say a director shoots a scene, and I think, “This is not working for me.” I would definitely say, “I don’t understand what’s happening here. It’s not working for me.” It’s not that I’m accusing him or anything. It’s more to get the dialogue going and maybe he will explain something to me that I didn’t think of, and I get guided into the right direction of how to handle that scene or the director will say, “No, you’re right. It’s completely fucked. We need to shoot it again.”

My biggest rule and only rule in the editing room is honesty. I have great respect for actors because they have to be so honest in their work on the screen. And I sincerely believe that that’s why some actors have such a great connection through the lens because they’re so honest. I sincerely believe that’s the reason. That’s why I respect what they bring to the table and the same goes for all of us that work in the film industry: we have to be honest about it.

So for me, the biggest thing is honesty. We have to be able to talk about things — difficult things. We have to be able to talk about ideas … So I do a lot of talking in the editing room. I think probably 70% of what I do is talk. Talk, talk talk. Talk about feelings; talk about the characters; talk about the story. Everyone is working for the same goal. Everyone wants the same thing. It’s just that the only way to get there together is through dialogue.

HULLFISH: You said the number one rule in your editing room is honesty and I’ve heard from so many people that the number one rule is trust.

RONALDSDOTTIR: Yeah, yeah, yeah. They go completely together. I wouldn’t go on a project if I didn’t have complete trust. It’s very difficult, to be honest without trust. If I didn’t trust the director I’d rather do something else. Film is an emotional art form. People are very emotional about their films and it’s an emotional journey to make a film. There is no way around that. So the whole emotion needs to be honest so the audience can trust when they watch the film. And they can hate it or love it, but they have to be honest about it. That’s my opinion. My super inflated ego opinion of what I think… I do take my work seriously but I don’t think people should take themselves too seriously, it can cause all kinds of health problems.

HULLFISH: You said that the day you stop learning is the day you have to find something else to do. So often our mistakes are what teach us something. What was the last mistake you made that taught you something?

RONALDSDOTTIR: Well, OK, now you got me cornered. But I am learning more and more that there are no mistakes in editing, there are choices. And of course your choices might not be right, but if you made them with honesty and respect for the story and for the characters then that´s the best you can do. And this is one of the things that´s so amazing working with David Leitch, because he´s so willing to risk “mistakes” in order to experiment with story and character. I mean the past year with Atomic Blonde was just like a roller coaster in discovering new ideas and approaches to experiment with what works for an audience and what doesn’t. And as a result, I feel like we extended the form of storytelling in a sense. Everything may have been done before, but we just haven´t done it before. So at least we got to expand our experience of storytelling.

HULLFISH: Do you have anything to say about any of these scenes from Atomic Blonde?

This is when Lorraine goes to meet Lasalle. Beautifully shot by Jonathan Sela. I believe we had a two-minute track of Lorraine walking up to the bar, but as stunning as it was we cut it down for the sake of pacing. We did cut out some dialogue and, as in many other scenes, it was a challenge as they are always both in frame. We all know Charlize Theron is an amazing actress but Sofia Boutella was a discovery for me, I find her amazing as well.

I was editing on set for this scene as it’s meant to feel as one single take. We shot it chronologically and tested each edit to make sure it was working. I did it on my laptop and got playback files from the camera on a memory stick. I worked closely with our VFX supervisor from Berlin, Michael Wortmann, we proudly claim we invented the Budapest stitch but it was freezing cold and I can’t remember the details of that genius invention, but it worked.

Lorraine is taking an ice-bath to ease the consequences of her earlier fights. The wide shot of the room is repurposed from the beginning of this scene that we cut out and we slightly zoomed digitally into it to add movement and tension. Also, when Lorraine attacks Percival with the bottle I did a split screen in order to delay Percival’s reaction to it. This was such a fun scene to edit, also the dialog that follows but is not included in this clip, as the chemistry between Theron and McAvoy is so charged.

HULLFISH: Thank you so much for your time. I really appreciate it. It was an absolute delight to talk to you.

RONALDSDOTTIR: Thank you. Same and I hope you like the movie when you see it.

This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

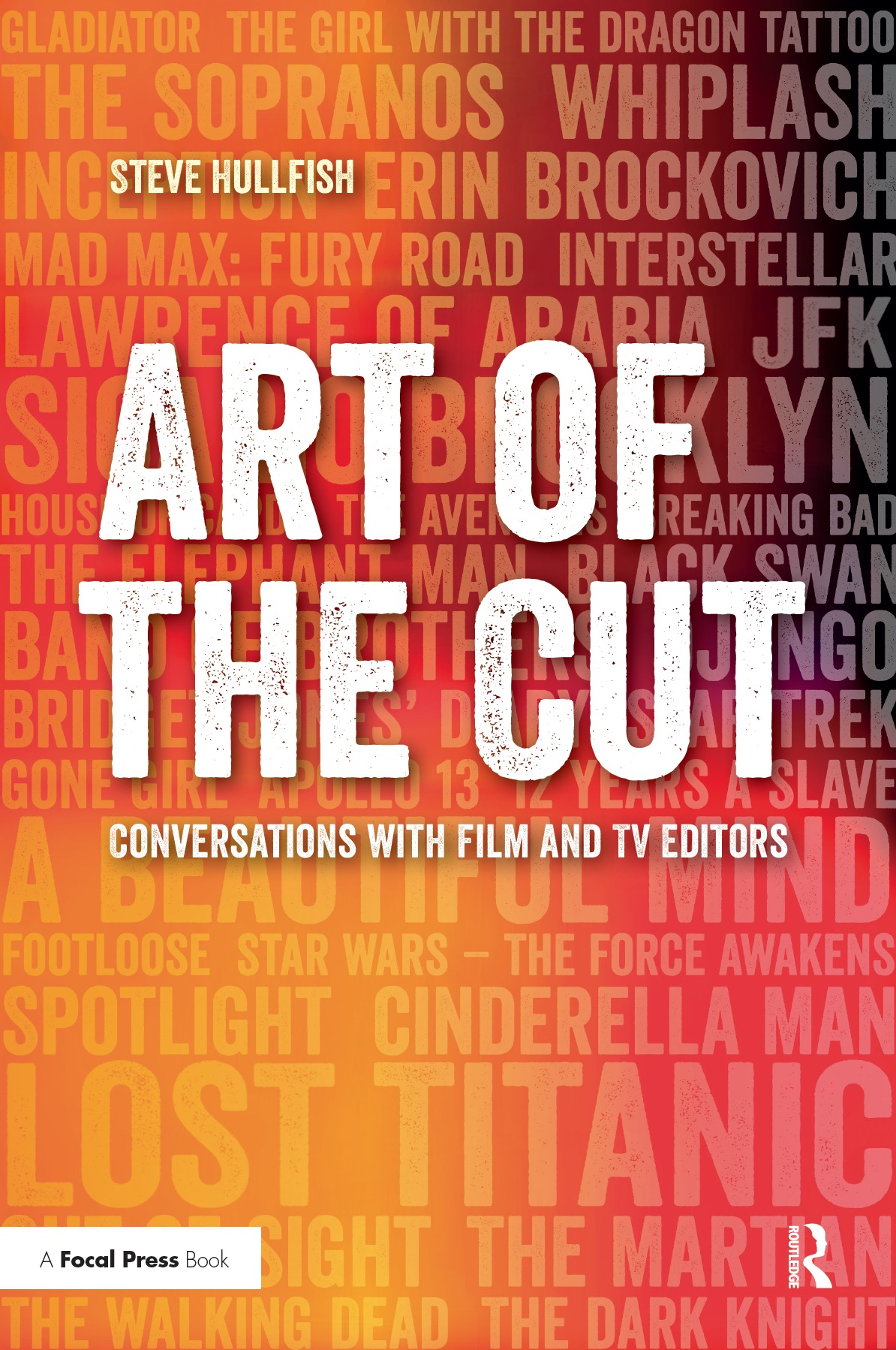

The first 50 Art of the Cut interviews have been curated into a book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV editors.” The book is not merely a collection of interviews, but was edited into topics that read like a massive, virtual roundtable discussion of some of the most important topics to editors everywhere: storytelling, pacing, rhythm, collaboration with directors, approach to a scene and more. Oscar nominee, Dody Dorn, ACE, said of the book: “Congratulations on putting together such a wonderful book. I can see why so many editors enjoy talking with you. The depth and insightfulness of your questions make the answers so much more interesting than the garden variety interview. It is truly a wonderful resource for anyone who is in love with or fascinated by the alchemy of editing.” In CinemaEditor magazine, Jack Tucker, ACE, writes: “Steve Hullfish asks questions that only an editor would know to ask. … It is to his credit that Hullfish has created an editing manual similar to the camera manual that ASC has published for many years and can be found in almost any back pocket of members of the camera crew. … Art of the Cut may indeed be the essential tool for the cutting room. Here is a reference where you can immediately see how our contemporaries deal with the complexities of editing a film. … Hullfish’s book is an awesome piece of text editing itself. The results make me recommend it to all. I am placing this book on my shelf of editing books and I urge others to do the same.”

The first 50 Art of the Cut interviews have been curated into a book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV editors.” The book is not merely a collection of interviews, but was edited into topics that read like a massive, virtual roundtable discussion of some of the most important topics to editors everywhere: storytelling, pacing, rhythm, collaboration with directors, approach to a scene and more. Oscar nominee, Dody Dorn, ACE, said of the book: “Congratulations on putting together such a wonderful book. I can see why so many editors enjoy talking with you. The depth and insightfulness of your questions make the answers so much more interesting than the garden variety interview. It is truly a wonderful resource for anyone who is in love with or fascinated by the alchemy of editing.” In CinemaEditor magazine, Jack Tucker, ACE, writes: “Steve Hullfish asks questions that only an editor would know to ask. … It is to his credit that Hullfish has created an editing manual similar to the camera manual that ASC has published for many years and can be found in almost any back pocket of members of the camera crew. … Art of the Cut may indeed be the essential tool for the cutting room. Here is a reference where you can immediately see how our contemporaries deal with the complexities of editing a film. … Hullfish’s book is an awesome piece of text editing itself. The results make me recommend it to all. I am placing this book on my shelf of editing books and I urge others to do the same.”

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now