Paul Machliss is a UK-based editor who has been in TV and film post since the late 1990s. Machliss was an obvious choice to edit the musically driven Baby Driver because of his long-time collaboration with director Edgar Wright – going back to their years in TV – and his numerous projects as an editor on music projects like Diana Krall: Live in Paris, The Led Zeppelin DVD, and New Order: 5 11 Live in Finsbury Park. Machliss also cut Man Up (2015), The World’s End (2013) and Edgar Wright’s previous film as director, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World.

HULLFISH: The music is so integral and so tightly woven into the fabric of Baby Driver. Can you tell me about working with the music for the film?

MACHLISS: We’d have to go way back for the beginning of the story of the music for Baby Driver. (Director) Edgar Wright and I have worked together for years – going back to when I was an on-line editor for him on the first series of his Channel 4 TV Series “Spaced”, and we would both bring in music to listen to during the interminably long render times – this is before the days of iPods – and we would have batches of CDs and try to outdo each other playing a game of “Yes, but have you heard THIS?” We both had pretty diverse and eclectic tastes in music. I think in the end, I may have won that contest, just because some of my music was quite unlistenable.

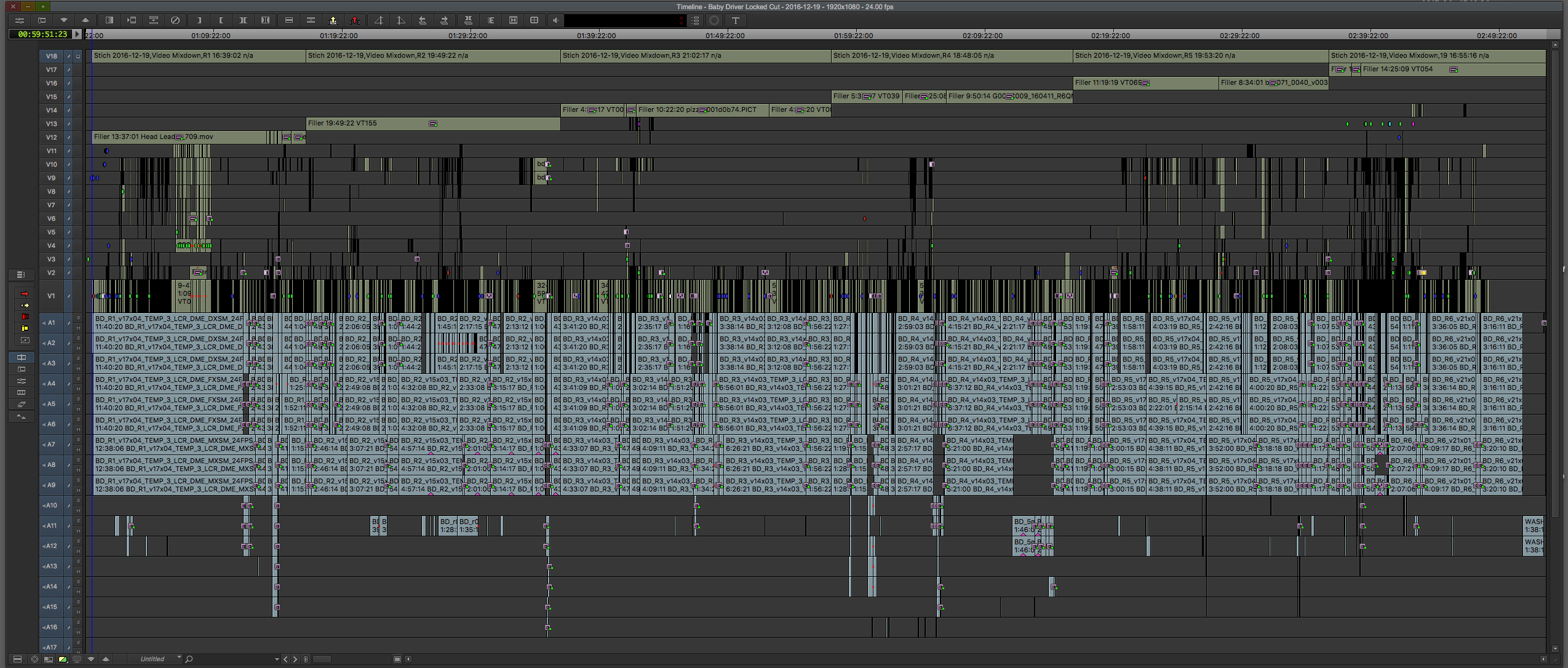

Over the years, as Edgar wrote Baby Driver he chose suitable songs to suit the scenes and constructed the script in and around that music. In 2012 Edgar did a table read of the script in LA and he sent me the audio of the read and in my down-time I combined that together with his chosen songs and sound effects and we ended up with what was essentially a 100-minute radio play of the film. Then in 2015 Edgar and L.A. based editor Evan Schiff created animatics for all the major action scenes so Edgar and the stunt team could start planning out the routines and time various bits of action to specific points in the various songs. When I arrived in Atlanta in January of 2016 I filled in the remaining ‘gaps’ in the animatics and prior to shooting we were able to screen the entire film to the H.O.D.’s (Heads Of Departments) as one long animatic.

HULLFISH: I have a background as an on-line editor, too. We’re probably the only on-line guys on the planet that transitioned to feature film cutting. It’s a weird path. Do you think your background as a musician helps? I grew up playing music and I think that even beyond having a built-in sense or rhythm and pace, it also gives you a great ability to sense patterns.

MACHLISS: Oh absolutely. Having learnt piano as a kid I was very comfortable with the idea of editing to music and understanding the dynamics, not only of the music, but also of the pace and rhythm of the picture cutting. Dynamics are so important. In classical music, you don’t just have everything dialed up to ten the whole time. You have moments of quiet. You have moments of emphasis. There are fast moments and slow moments. Picture editing also has to be like that. For example in Baby Driver, there’s a scene of Baby and Debora – his girlfriend – in the diner. Edgar had the whole thing beautifully covered, of course. But there’s a point when she asks him about his mom and he starts to remember her and these powerful emotions play over his face. I didn’t want to cut away. We had this great tracking shot into him, and even though Debora continues talking and asking him questions, I just stayed on Ansel for a long time – maybe 20 seconds. It felt like the right thing to do. The dynamics of it were right to slow down at that moment. I showed that cut to Edgar and he loved it. He loved just holding on that shot.

HULLFISH: You were actually on-set for almost the entire movie. Tell me a little about why that was and how it worked.

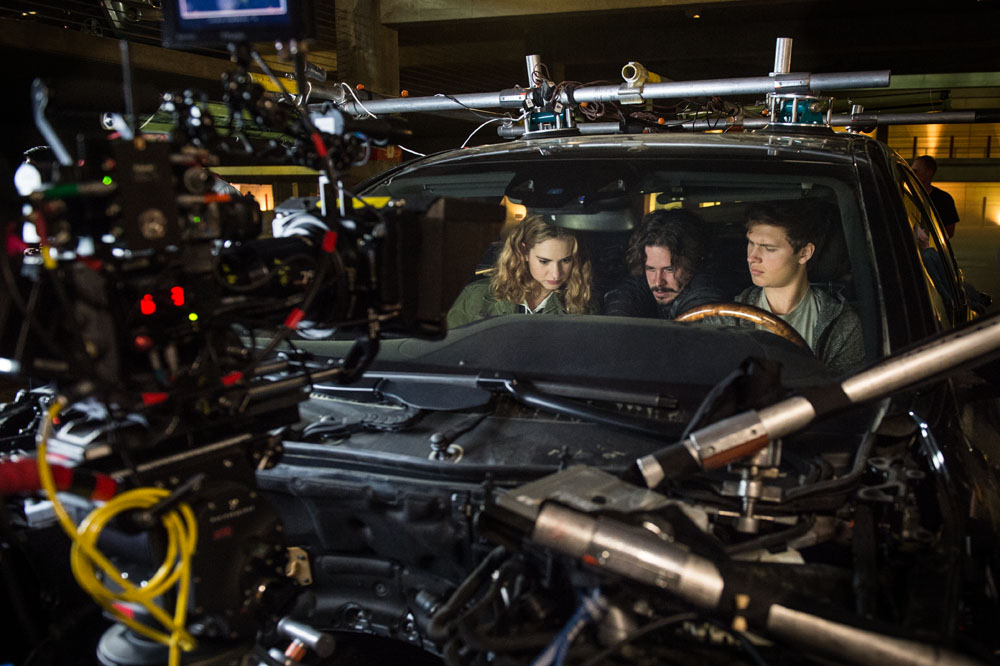

MACHLISS: As the editing played a role complementary to that of the filming – particularly for a film of this nature – Edgar requested that I work on set so we could check that everything was falling into place as the scene was being constructed and shot. Practically, this meant that I had a little trolley (wheeled cart) donated by the sound department and I had my laptop running Avid Media Composer along with a monitor and a few hard drives. I was connected directly to the video assist’s hard drive via an ethernet cable and created a network between my computer and his hard driver. He was recording the video tap from the Panavision cameras and within a few seconds of Edgar yelling “Cut” I could see his new Quicktime file show up on my Finder window. I’d use AMA-linking to instantly move the file into an Avid bin and I’d cut it in immediately on to the timeline. As we were shooting on film the picture quality wasn’t the same as what you would get from an Arri Alexa however it was good enough to edit with. I didn’t get to see the real full-res files until I was back in the cutting room.

HULLFISH: You guys were shooting scenes and takes and action out of order, so were you cutting the video-assist footage over the animatic that had been done?

MACHLISS: Yes. I had all of the music on my system already and I had the animatic broken up into scenes, so I could cut the video-tap footage in and make sure that it fit properly. Because Edgar had planned all of the scenes very intricately around these songs, it wasn’t like a normal movie, where if a shot went a second or two long, you could just let it go. Every line or beat in a song was a shot and we couldn’t change the music, so each shot needed to end before the next shot could begin. We had top choreographer Ryan Heffington on set, and even actions like setting a loaf of bread down on the counter had to be counted in: “5, 6, 7, 8…” and that shot needed to be complete at the right time so we could go to the next shot for the next line.

Occasionally Edgar would turn to me and ask, “Do we have it, Paul? Are we good?” And, if I was quick enough, I’d already have it cut in and I could say, “Yes. We’re good.” It was really cool to be on set and part of the crew. Usually, we’re locked away in our dark, little rooms and the editing is just this kind of dark art that nobody understands. I think the crew – at the beginning – thought I was this strange oddity: “What’s that guy doing with the laptop over there? Why does the director keep asking him if we got it?” But eventually, they could see and understand what I was doing. There was a scene where Ansel’s in the parking lot and trying to hide from the police and simultaneously hot-wire a car. It was a full day there shooting that scene and at the end of it, they could gather some of the production staff around the monitor and view that day’s material cut together. Usually the crew doesn’t get a chance to see that. Normally the director yells ‘Cut!’ and the next time the crew sees anything, it’s at the premiere. They were actually able to see it cut in place and working before we even wrapped for the day. Some of them were probably thinking, “What kind of dark magic is this?”

HULLFISH: That must have made for some complex on-set audio.

MACHLISS: All of the actors were wearing earpieces and they were being fed the music so they could sync their actions to it if they needed to. Edgar had headphones that were being fed music into one ear and dialogue into another. Everybody needed to have a different feed of audio with different splits. Sound recordist Mary Ellis also was generating time-of-day timecode while the music playback was sending me the timecode associated with the WAV file of the track. All of that was needed so my 1st Assistant Editor Jerry Ramsbottom could sync back the video-tap footage I was editing with to the final scanned telecine rushes that we would get a few days later. Jerry would use that timecode – and sometimes resort to eye-matching – to cut the scanned film footage back over the video-tap footage I was using. It was a very complex audio set-up and we only really worked it out on the first day of our first big dialogue scene we shot in the diner. Edgar asked if he could have the split audio feed in his cans – plus we needed to make sure the actors could hear the music in their earpieces which had to be controlled independently of the music being sent to Edgar’s headphones. The dialogue-only track had to be recorded to the Video Assist machine but then I also needed a split feed of music and dialogue for the Avid. We were all gathered in this back room trying to figure out how to split up the audio feeds and what needed to be upstream and what needed to be split at some other point. We were all hustling to figure out a way to do it. Meanwhile on set they’ve already started to shoot the scene so we had to rig this up pretty quickly. But we eventually figured it all out and that’s the way we ran the audio for the rest of the shoot.

HULLFISH: It’s interesting that you were shooting film. I grew up in Rochester, NY, the home of Eastman Kodak, so I’m all for that.

MACHLISS: Edgar has always been big on film. There’s just something about the look of it. It’s the imagery we remember from our childhood, watching E.T. and Close Encounters and Raiders of the Lost Ark. We actually did a bunch of side-by-side tests. We had a screening room in Atlanta and we shot film and then digital with the ARRI Alexa and we projected them side-by-side, in a blind test. Every time, Edgar and I would point to the real film footage and say, “That one! Absolutely, that one!” We shot about 90% of the film on 35mm. There were some night scenes where the Alexa could shoot in lower light, so we used it there and there were also some very tight spots where we needed to get a camera, and we used the Alexa Mini for those shots as well.

It was really important for Edgar to capture as much of this as possible in-camera. Almost all of that car chase stuff is completely real. Very little is CGI. I actually read some reviewer complimenting a CGI shot of the car spinning 180 degrees and then back 180 again, but that was completely practical. I’ve got to hand it to the stunt drivers and coordinators. We shut down a whole section of the I-85 in Atlanta to get that opening car chase footage for the “Bellbottoms” song. We actually had to shut it down twice, because we didn’t get it all the first time. For two separate Sundays, one half of Atlanta couldn’t get to the other half of Atlanta. We rarely shot with green screen. I’m sure the insurance people and the health and safety people were just saying, “Shoot with green screen! Use CGI crashes!” But Edgar wanted that stuff to look real.

HULLFISH: So you get done cutting on set and then you have to go back to do the director’s cut.

MACHLISS: Getting the director’s cut done was very tight. Because I’d been on-set the whole time, I didn’t really get to clean up the scenes. Usually, if you get a scene cut at the end of the day, and it’s not quite right, you can take some time the next day and take care of whatever the issues are, but every day, I needed to be cutting exactly what they were shooting, so there were definitely some scenes that needed more work than they would have if we had been doing a more traditional edit. And then when we got back to London, Jonathan Amos joined us. Jonathan and I had worked together before on Scott Pilgrim vs. the World and he came on board to primarily work on the action sequences. He picked up on where I left off on the scenes from on-location and did a fantastic job. While he was doing that, Edgar and I were working on story and dialogue and Edgar would go back and forth between the two cutting rooms. The schedule for production was that we were shooting in Atlanta from (February to May), then the director’s cut which lasted until early August. We did a few screenings for test audiences and the feedback we received was increasingly positive. Off the back of that we were able to get the studio to approve a few more days of additional photography to improve a few sections Edgar wasn’t totally happy with.

HULLFISH: What did you reshoot or add?

MACHLISS: We didn’t reshoot any driving stuff. It was mainly story. We concentrated on the relationship between Baby & Debora. We embellished the final scene between Buddy and Baby. Back in London we also re-worked the very ending in the edit to add a hint of ambiguity.

HULLFISH: I would totally want to see a continuation of that story.

MACHLISS: The studio’s definitely asked Edgar if he could write another one. The irony is that we talked so much about having the audience go see this movie because it is original and not a remake or a sequel, and then, what happens? They ask for a sequel.

HULLFISH: I’ve talked to many editors about these audience screenings. You get notes back, but you don’t really need those do you?

MACHLISS: No. Not at all. I remember being at a screening of a film I worked on a few years back – ‘Man Up’ – which starred Simon Pegg and Lake Bell… there’s a scene at the end where Simon’s doing a little monologue and I was sitting in the back of the theater and the director and I could hear people slowly begin to sniffle. It’s so powerful when you realize you’ve affected an audience. People were really getting a little moist around the eyelids. You can definitely tell the moments in the movie that you have the audience’s attention and the moments when you’re starting to lose them.

HULLFISH: You had some great actors and definitely a great director, so you had some wonderful performances to begin with, but there are still times when you have to mold a performance or you have to regulate the temperature of a performance in a specific scene for one reason or another.

MACHLISS: That’s true. After the first test screening we felt there were a few scenes that could be improved. We felt we could add some more warmth or and have the audience connect better with the characters. Edgar and I went back in and dug around for some reaction shots and some slightly different readings of lines. Without really changing the dialogue or the story – because we really liked the structure of the scene and the way it played and we didn’t want to change that – we were able to really change the audience perception of the characters based on just a few reaction shots and changes of takes.

HULLFISH: What about the story and the structure of the story? Did that change, or had it really been worked out so well in the “radio play” version and the animatic that the story issues had been dealt with before shooting?

MACHLISS: No, the table read was really done with a version of the script that was altered quite a bit from the final version of the film. There was four years between that table read and the shoot so for all sorts of reasons things will and can change. But Edgar constructs a very tight script so he’s able to seamlessly able to deal with any issues that arise when out of necessity changes need to be made.

HULLFISH: Were there any editing surprises as Jon took over the big action sequences and stunts?

MACHLISS: We did find that there were some things that we had planned out in the animatics that just couldn’t happen. You drop in a drawing of a car crashing and you cut that in for two seconds and then when you actually run two cars into each other or try to flip a car over for real, you realize that the laws of physics come in to play and it actually takes much more time … there’s just no way to make a car do what you want it to do in the space of time you’ve allocated in the song.

HULLFISH: Well, all of that action was all timed to the music, so what happens then?

MACHLISS: We had to get creative. We had to make some cuts in the music. Sometimes Jon had to lengthen the song and sometimes we’d have to loop a section. We’d find some spot in the song and we figured we could loop it cleanly over a little riff and once it was mixed in with all the other sound effects the audience would never be aware of it.

HULLFISH: It was great talking to you today. Thanks for sharing.

HULLFISH: It was great talking to you today. Thanks for sharing.

MACHLISS: My pleasure.

Watch the first six minutes of Baby Driver:

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 Art of the Cut interviews have been curated into a book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV editors.” The book is not merely a collection of interviews, but was edited into topics that read like a massive, virtual roundtable discussion of some of the most important topics to editors everywhere: storytelling, pacing, rhythm, collaboration with directors, approach to a scene and more. Oscar nominee, Dody Dorn, ACE, said of the book: “Congratulations on putting together such a wonderful book. I can see why so many editors enjoy talking with you. The depth and insightfulness of your questions makes the answers so much more interesting than the garden variety interview. It is truly a wonderful resource for anyone who is in love with or fascinated by the alchemy of editing.” In CinemaEditor magazine, Jack Tucker, ACE, writes: “Steve Hullfish asks questions that only an editor would know to ask. … It is to his credit that Hullfish has created an editing manual similar to the camera manual that ASC has published for many years and can be found in almost any back pocket of members of the camera crew. … Art of the Cut may indeed be the essential tool for the cutting room. Here is a reference where you can immediately see how our contemporaries deal with the complexities of editing a film. … Hullfish’s book is an awesome piece of text editing itself. The results make me recommend it to all. I am placing this book on my shelf of editing books and I urge others to do the same.”

The first 50 Art of the Cut interviews have been curated into a book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV editors.” The book is not merely a collection of interviews, but was edited into topics that read like a massive, virtual roundtable discussion of some of the most important topics to editors everywhere: storytelling, pacing, rhythm, collaboration with directors, approach to a scene and more. Oscar nominee, Dody Dorn, ACE, said of the book: “Congratulations on putting together such a wonderful book. I can see why so many editors enjoy talking with you. The depth and insightfulness of your questions makes the answers so much more interesting than the garden variety interview. It is truly a wonderful resource for anyone who is in love with or fascinated by the alchemy of editing.” In CinemaEditor magazine, Jack Tucker, ACE, writes: “Steve Hullfish asks questions that only an editor would know to ask. … It is to his credit that Hullfish has created an editing manual similar to the camera manual that ASC has published for many years and can be found in almost any back pocket of members of the camera crew. … Art of the Cut may indeed be the essential tool for the cutting room. Here is a reference where you can immediately see how our contemporaries deal with the complexities of editing a film. … Hullfish’s book is an awesome piece of text editing itself. The results make me recommend it to all. I am placing this book on my shelf of editing books and I urge others to do the same.”

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now