Two components are involved to meet proper ADA compliance: closed captions and described audio (aka audio descriptions). Captions come in two flavors – open and closed. Open captions or subtitles consists of text “burned” into the image. It is customarily used when a foreign language is spoken in an otherwise English program (or the equivalent in non-English-speaking countries). Closed captions are enclosed in a data stream that can be turned on and off by the viewer, device, or the platform and are intended to make the dialogue accessible to the hearing-impaired. Closed captions are often also turned on in noisy environments, like a TV playing in a gym or a bar.

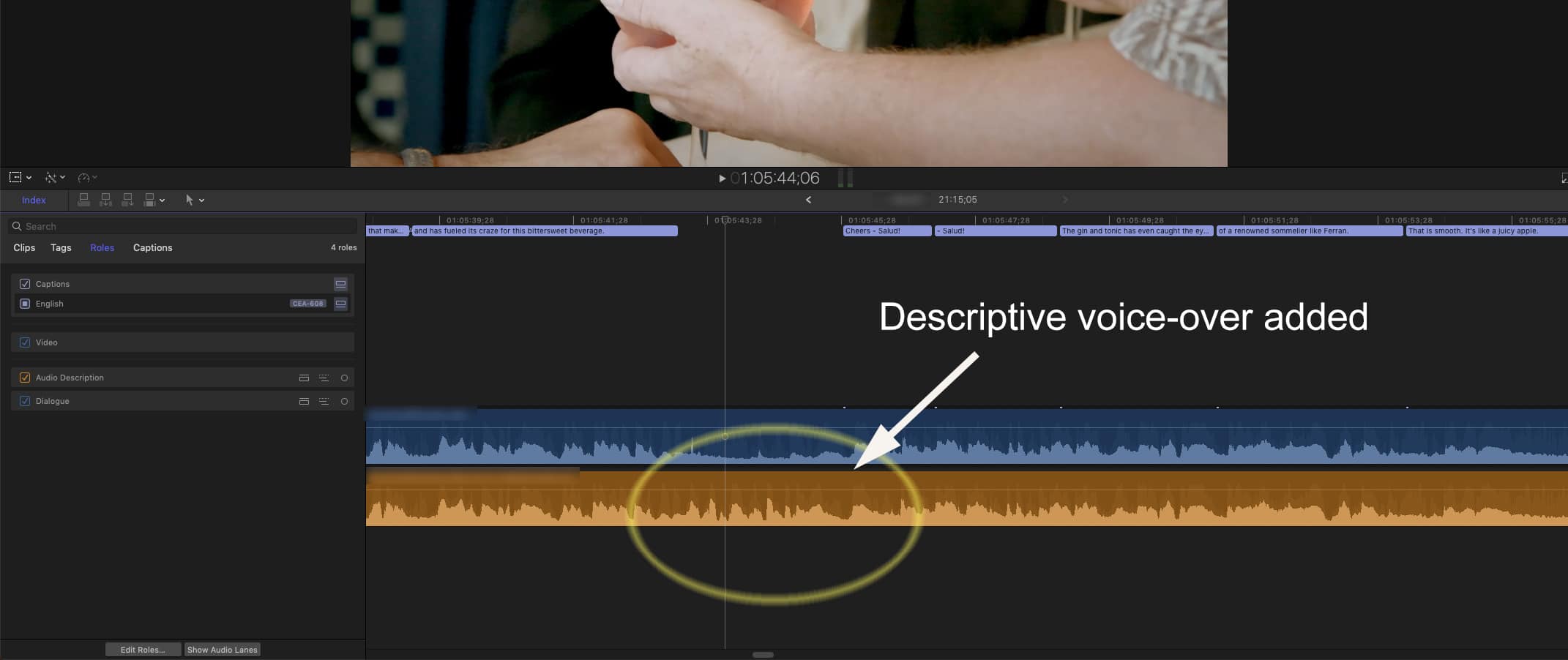

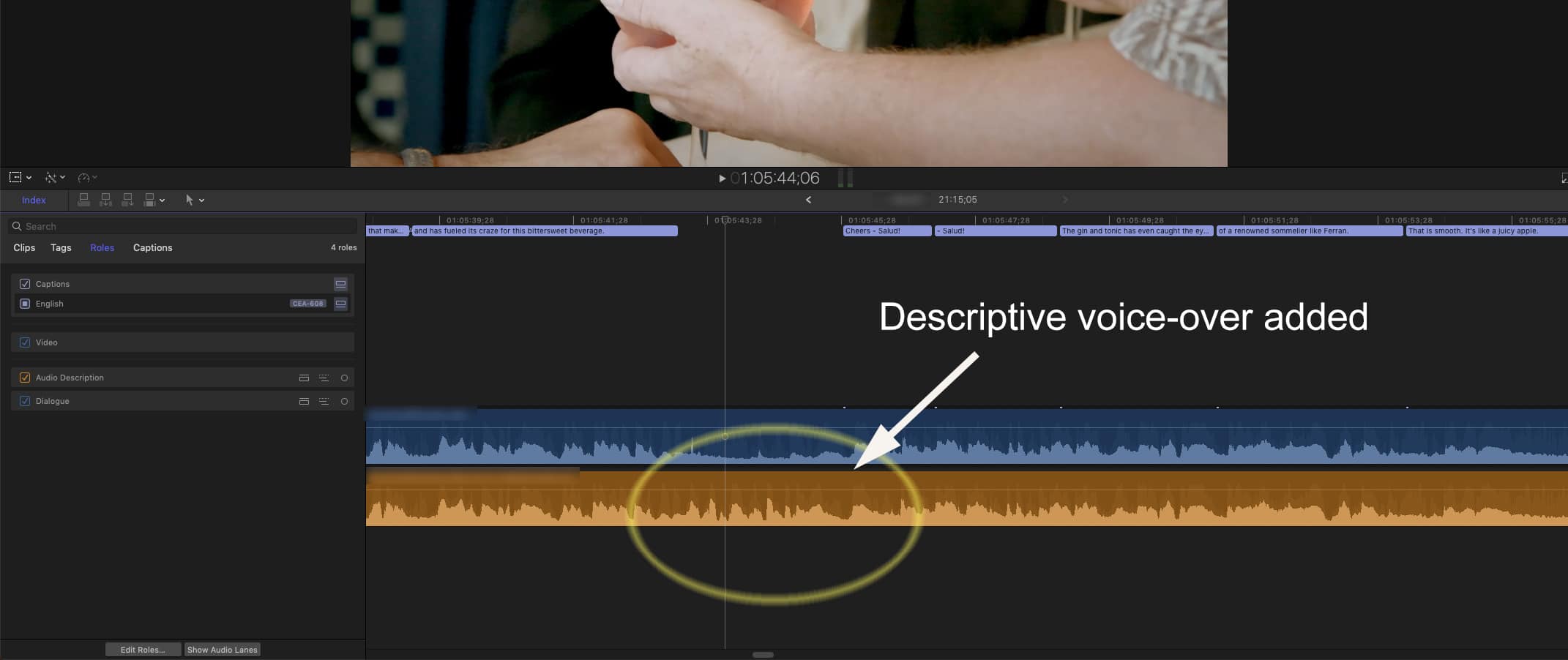

Audio descriptions are intended to aid the visually-impaired. This is a version of the audio mix with an additional voice-over element. An announcer describes visual information that is not readily obvious from the audio of the program itself. This voice-over fills in the gaps, such as “man climbs to the top of a large hill” or “logos appear on screen.”

Historically post houses and producers have opted to outsource caption creation to companies that specialize in those services. However, modern NLEs enable any editor to handle captions themselves and the increasing enforcement of ADA compliance is now adding to the deliverable requirements for many editors. With this increased demand, using a specialist may become cost prohibitive; therefore, built-in tools are all the more attractive.

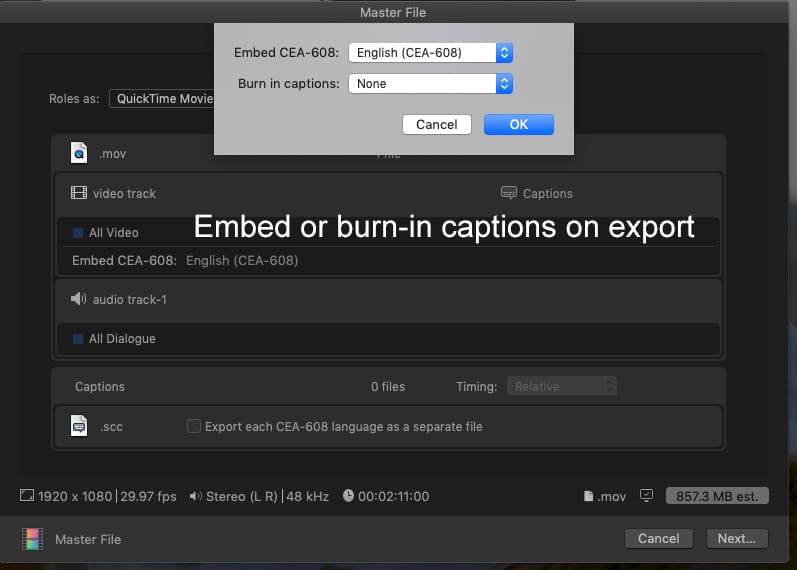

There are numerous closed caption standards and various captioning file formats. The most common are .scc (Scenarist), .srt (SubRip), and .vtt (preferred for the web). Captions can be supplied as “embedded” (secondary data within the master file) or as a separate “sidecar” file, which is intended to play in sync with the video file. Not all of these are equal. For example, .scc files (embedded or as sidecar files) support text formatting and positioning, while .srt and .vtt do not. For example, if you have a lower-third name graphic come on screen, you want to move any caption from its usual lower-third, safe-title position to the top of the screen while that name graphic is visible. This way both remain legible. The .scc format supports that, but the other two don’t. The visual appearance of the caption text is a function of the playback hardware or software, so the same captions look different in QuickTime Player versus Switch or VLC. In addition, SubRip (.srt) captions all appear at the bottom, even if you repositioned them to the top, while .vtt captions appear at the top of the screen.

Getting the right look

There are guidelines that captioning specialists follow, but some are merely customary and do not affect compliance. For example, upper and lower case text is currently the norm, but you’ll still be OK if your text is all caps. There are also accepted norms when English (or other) subtitles appear on screen, such as for someone speaking in a foreign language. In those cases, no additional closed caption text is used, since the subtitle already provides that information. However, a caption may appear at the top of the screen identifying that a foreign language is being spoken. Likewise, during sections with only music or ambient sounds, a caption may briefly identify it as such.

When creating captions, you have to understand that readability is key, so the text will not always run perfectly in sync with the dialogue. For instance, when two actors engage in rapid-fire dialogue, each caption may stay on longer than the spoken line. You can adjust the timing against that scene so that they eventually catch up once the pace slows down. It’s good to watch a few captioned programs before starting from scratch – just to get a sense of what works and what doesn’t.

Using your NLE to create closed captions

Avid Media Composer, Adobe Premiere Pro, DaVinci Resolve, and Apple Final Cut Pro X all support closed captions. I find FCPX to be the best of this group, because of its extensive editing control over captions and ease of use. This includes text formatting, but also display methods, like pop-on, paint-on, and roll-up effects. Import .scc files for maximum control or extract captions from an existing master, if your media already has embedded caption data. The other three NLEs place the captions onto a single data track (like a video track) within which captions can be edited. Final Cut Pro X places them as a series of connected clips, like any other video clip or graphic. If you perform additional editing, the FCPX magnetic timeline takes care of keeping the captions in sync with the associated dialogue.

Final Cut’s big plus for me is that validation errors are flagged in red. Validation errors occur when caption clips overlap, may be too short for the display method (like a paint-on), are too close to the start of the file, or other errors. It’s easy to find and fix these before exporting the master file.

NLEs support the export of a master file with embedded captions, or “burned” into the video as a subtitle, or the captions exported as a separate sidecar file. Specific format support for embedded captions varies among applications. For example, Premiere Pro – as well as Adobe Media Encoder – will only embed captioning data when you export your sequence or encode a file as a QuickTime-wrapped master file. (I’m running macOS, so there may be other options with Windows.)

On the other hand, Apple Compressor and Final Cut Pro X can encode or export files with embedded captions for formats such as MPEG2 TS, MPEG 2 PS, or MP4. It would be nice if all these NLEs supported the same range of formats, but they don’t. If your goal is a sidecar caption file instead of embedded data, then it’s a far simpler and more reliable process.

Compared to closed captions, providing audio description files is relatively easy. These can either be separate audio files – used as sidecar files for secondary audio – or additional tracks on the delivery master. Sometimes it’s a completely separate video file with only this version of the mix. Advanced platforms like Netflix may also require an IMF (Interoperable Master Format) package, which would include an audio description track as part of that package. When audio sidecar files are requested for the web or certain playback platforms, like hotel TV systems, the common deliverable formats are .mp3 or .m4a. The key is that the audio track should be able to run in sync with the rest of the program.

Producing an audio description file doesn’t require any new skills. A voice-over announcer is describing any action that occurs on screen, but which wouldn’t otherwise make sense if you were only listening to audio without that. Think of it like a radio play or podcast version of your TV program. This can be as simple as fitting additional VO into the gaps between actor/host/speaker dialogue. If you have access to the original files (such as a Pro Tools session) or dialogue/music/effects stems, then you have some latitude to adjust audio elements in order to fit in the additional voice-over lines. For example, sometimes the off-camera dialogue may be moved or edited in order to make more space for the VO descriptions. However, on-camera/sync dialogue is left untouched. In that case, some of this audio may be muted or ducked to make space for even longer descriptions.

Some of the same captioning service providers also provide audio description services, using their pool of announcers. Yet, there’s nothing about the process that any producer or editor couldn’t handle themselves. For example, scripting the extra lines, hiring and directing talent, and producing the final mix only require a bit more time added to the schedule, yet permits the most creative control.

ADA compliance has been around since 1990, but hasn’t been widely enforced outside of broadcast. That’s changing and there are no more excuses with the new NLE tools. It’s become easier than ever for any editor or producer to make sure they can provide the proper elements to touch every potential viewer.

The FCC also has a good read on captioning: Closed Captioning on Television.