Moving Stills enables any photograph to become an animated 3D image with a realistic effect of flying through the photo. It’s not wizardry, but a process with roots in experiments from 20 years ago.

We’ve Cinemagraphs, Cliplets, Plotagraphs and other formats that introduce animation to photos, like the good old Animated GIF, but soon we may have Moving Stills, Adobe’s own solution to animate images. Revealed at Adobe MAX, along with many other technologies the company is exploring and developing – some of which might never see the light of day – Moving Stills managed to get the crowd excited at the presentation and while it is, apparently, a new step, it’s based in something being studied since at least the mid 90s. A trio of Hitachi researchers presented, at Siggraph 1997, a paper entitled “Tour Into the Picture”.

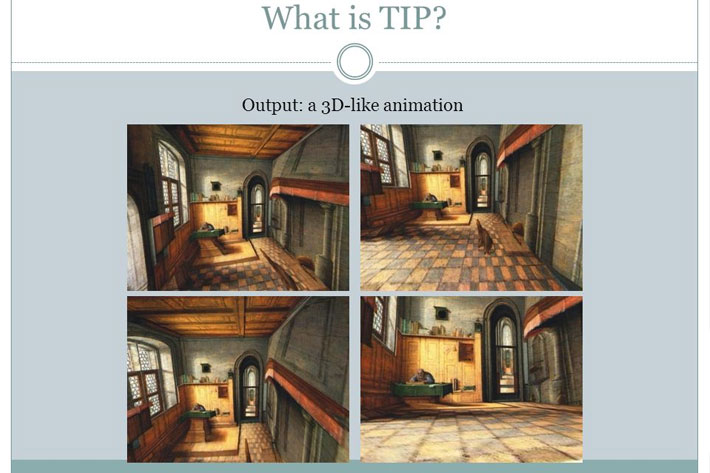

The team, Youichi Horry, Ken-ichi Anjyo and Kiyoshi Arai, published a nine-page document, subtitled “Using a Spidery Mesh Interface to Make Animation from a Single Image”, which explains a new method called TIP (Tour Into the Picture) for easily making animations from one 2D picture or photograph of a scene. According to the information published then, “in TIP, animation is created from the viewpoint of a camera which can be three-dimensionally ‘walked or flown through’ the 2D picture or photograph.”

https://youtu.be/dM-lX9c3Pqw

According to the paper, “to make such animation, conventional computer vision techniques cannot be applied in the 3D modeling process for the scene, using only a single 2D image. Instead a spidery mesh is employed in our method to obtain a simple scene model from the 2D image of the scene using a graphical user interface. Animation is thus easily generated without the need of multiple 2D images.”

Multiple experiences online

The conclusions of the document indicate that “Creating 3D animations from one 2D picture or photograph of a 3D scene is possible for a skilled animator but often very laborious, since precise information for making the 3D scene model cannot be extracted from the single 2D image. However, the incompleteness of 3D information derived from one image allows animators to create the 3D scene model in a more flexible way. In this paper we have proposed a new technique called TIP which provides a simple scene model that transforms the animator’s imaginings into reality. The key to our method lies in the GUI using a spidery mesh, which allows animators to easily model the 3D scene. This lets animators utilize the incomplete 3D scene information to freely create scenery to their liking and obtain enjoyable and ‘visually 3D’ animations.”

https://youtu.be/yiz1_cI2NUE

So, that was 21 years ago. Since then, multiple examples of ways to create 3D images from 2D originals have been made available online, on YouTube, and I picked some to illustrate this article. The Moving Stills demonstration from Adobe MAX is a similar process, and without having more information, it is difficult to know how more advanced it is than those previous efforts. The videos picked to illustrate the system in use help to understand what’s behind the magic. While a series of them use the same base image, some are rather interesting, like the one using a cover from a Beatles album.

Panning, zooming and more

Now that I’ve set a background for Moving Stills, with links that readers interested in the subject can follow, it’s time to comment on the example showed at Adobe MAX. The animations – both TIP and Moving Stills – are not perfect and reveal multiple problems that would stop anyone from using them for final presentations. Still, if this is technology in development, and Adobe intends to take it further than previous experiments, there may be some uses for it. No, it’s not new, or even revolutionary, but being able to animate a single image may, sometimes, be an interesting asset, and not just for photographers. Imagine you’re editing a video and need to include one still image but would like to give it some animation? If Moving Stills is a feature of the editor you’re working with, then you can.

https://youtu.be/hIptq3u89pQ

True, some of the animations shown on Moving Stills and the TIP examples are not very different from what you can do using zoom and panning in any video editor. Even photographers used to create slideshows are familiar with those techniques, which I’ve always used when creating digital slideshows in ProShow Producer. In fact, ProShow Producer allows, with special effects packs, to do much more, as illustrated in one of the videos published here. But some of the effects present in Moving Stills and TIP require a different approach that is not featured in the software now available.

3D and animated images

Moving Stills uses, according to Adobe, “deep learning powered by Adobe Sensei to generate videos from a single still image, something that would otherwise take an experienced artist hours to finish.” Again, we’ve AI or Artificial Intelligence as the base for everything demoed these days… making you wonder how two decades ago people managed to create things as TIP, when the AI concept and acronym were not around… Still, independently of the name, the magic returns.

https://youtu.be/9ClkyK5SeHY

Humans passion for 3D photographs and animated images is not new. From as early as 1851, stereo cameras attracted attention, and one century later, in 1953, 3D movies had a boom, using polarized stereo. Stereo anaglyphic photos were also popular, because although viewing them requires a pair of glasses – red and cyan, although red and green or red and blue are also used – they can be viewed in print, on a monitor or projected.

From Lascaux caves to flip books

Although tridimensional photography never really became mainstream, in 1992 Vivitar decided to introduce their Q-dos system and a lens capable of creating pseudo stereo anaglyphic photos, the Vivitar Series 1 70-210mm f/2.8-4 VMC, for 35mm SLR cameras. I saw the system at Photokina and have in my archive prints distributed by Vivitar at the time. The lens could be used as any other lens, but had the option to insert internally, through a switch, red and cyan dichroic filters that would create colour fringing in out-of-focus areas of the photo. With the 3D glasses provided with the lens, it was possible to see the effect. The effect was mostly visible with closeups, which was something the lens was good for, offering a reproduction ratio of 1:2.5 at 210mm. Despite the initial enthusiasm, the system did not last long, because there was no public for it.

https://youtu.be/-6IulITPEQo

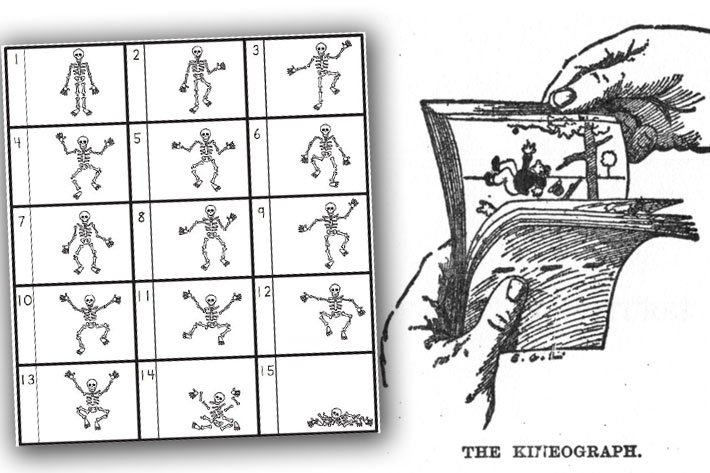

While 3D is less than 200 years old, animation may be a bit older. Suggestions of animation in drawing can be traced as far back as the Lascaux caves, starting 17,000 years ago, or, more recently, in the sequences of illustrations from Sigenot, an anonymous Middle High German poem from the XIV century. Leaving aside some 19th century animation devices, like the zoetrope, which produces the illusion of motion by displaying a sequence of drawings or photographs showing progressive phases of that motion, I would like to look, here, at the flip book, which is first documented in 1868, patented under the name kineograph, which means… moving picture. I believe, we are all familiar with flip books!

Moving Stills and Cinemagraphs

What interests me here is the name, which immediately reminds me of Moving Stills and… Cinemagraphs. Despite the fact that these are different systems, aiming to achieve different results, both are designed to animate one still photograph. It’s true that Cinemagraphs are built from a video or a sequence of images, while Moving Stills aims to create animation using a single photo, but the end goal is the same: to attract attention and make you go… wow!

https://youtu.be/sJVTnQL_Lug

Many of the critiques made to Moving Stills suggest that it is a gimmick that does not offer any interest for professional use. While at its current stage that may be true, if the project meets its goals, things may change. It may not be the tool that eveybody wants or needs, but some users may find ways to include it in their workflow. In fact, 2D photos are edited to create 3D effects using a paralax effects and separating the background and other planes in layers, for everything from websites to video. It’s a difficult task that Moving Stills can automate.

Cinemagraphs is, probably, the best example of a tool that was initially considered to be a fad, and has turned into a solution applied in areas as advertising. From the different animation solutions available, it is, from my point of view, the most interesting in terms of final results. There is only one problem with Cinemagraphs: it is only available for Mac, despite the fact that years ago I was told that a Windows version would probably be announced.

Now, just imagine that the key features of Cinemagraphs could be mixed with those from Moving Stills.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now