What makes a project good to work on?

I’ve worked on more productions than I can remember but some projects were definitely more enjoyable to work on than others. There were projects I thought would be great but turned out to be nightmares, and projects that sounded mundane that turned out to be hugely rewarding. The second After Effects project diary introduced this topic using an old project from early on in my career – making training videos for lawn bowls. The point of the article was that although it doesn’t sound very exciting it was actually very satisfying to work on a project where I had creative control.

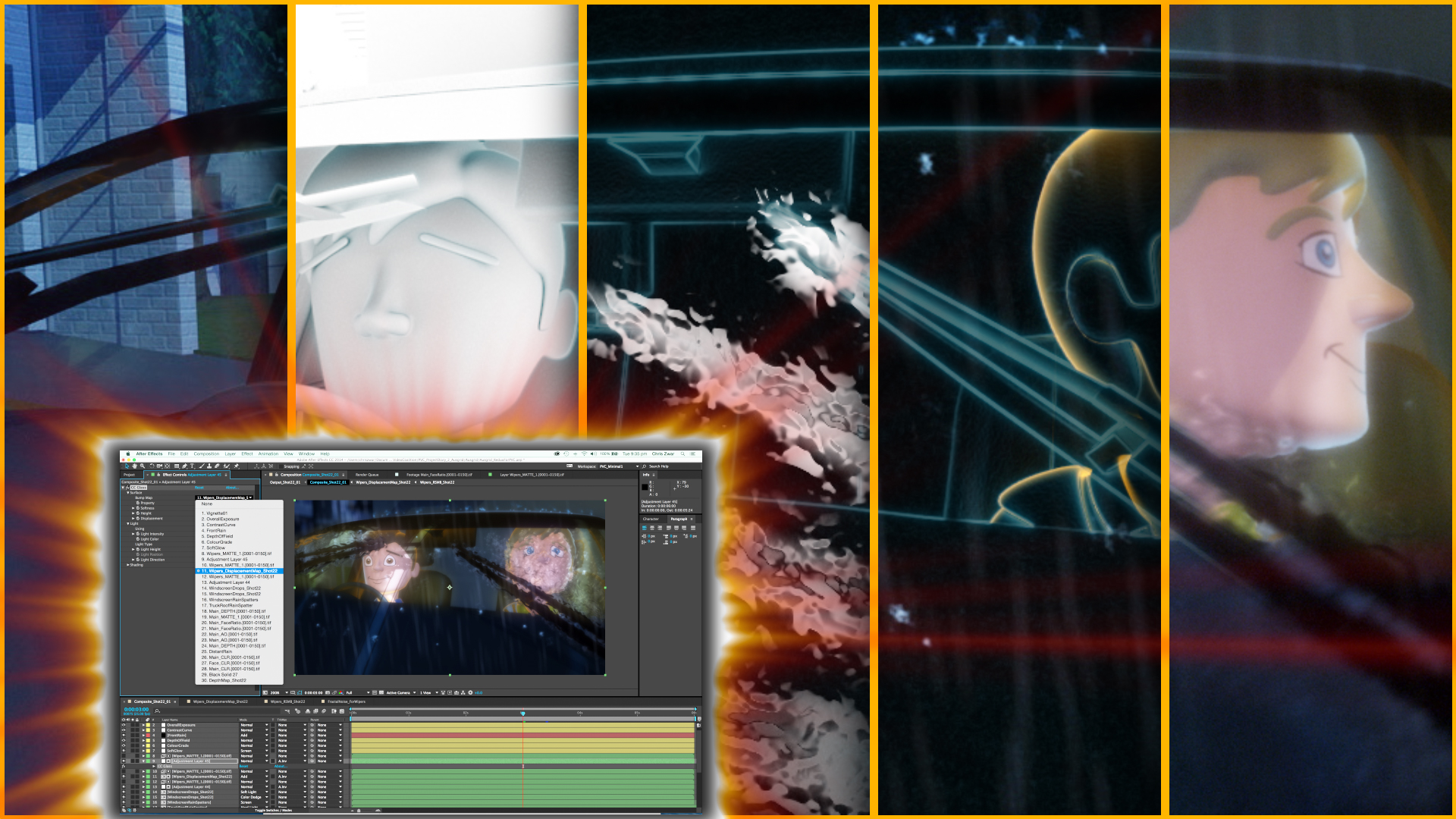

This time I’m going to use a more recent project (although it’s still about six years old) so I can take you through the After Effects compositions and demonstrate some of the compositing steps (skip to the bottom for some compositing breakdowns if you’re impatient).

While this project diary continues on from the last one with the theme that some projects turn out to be more enjoyable than others, I’m also introducing the idea that After Effects can be thought of as two different applications combined together. This project diary is the first in a series that will explore the role of After Effects as a visual fx compositing program, and the next few diaries will continue on from here and look at compositing in increasing detail.

But before we get into layers, let’s look at some of the basic details.

Ausgrid: vital statistics

This project was a series of 3 x 2 minute videos for Ausgrid, an Australian electricity provider. They were produced by Digital Pulse in Sydney (now simply known as “The Pulse”) and I think they were made in 2010. The videos were completely 3D animated and demonstrated the advances made by Ausgrid in dealing with electricity blackouts.

Ever wondered what happens when there’s a blackout? Wonder no more…

The first video showed how electricity companies had traditionally dealt with blackouts, while the 2nd video showed how advances in technology have dramatically improved response times. The 3rd video shows how continuing developments in technology will make it even faster to fix blackouts in the future.

In the studio, a core team of only four people produced all three videos. There was an overall Director / Art Director, two 3D animators using Maya, and myself as the compositor. Because these videos were pretty short and they had been tightly storyboarded in Final Cut Pro, the Director also acted as the editor – as shots progressed from frames to playblasts to final composites he updated the clips in FCP until the video was complete.

This was a very low budget project, with the 3D animators working for two weeks and myself for one (a week being five working days). Producing over five minutes of 3D animation in two weeks – especially when involving characters – is an incredible feat and a real testament to the talents of the guys who managed to do it.

In all, there were 33 shots that needed to be composited, and the plan was for me to do the initial composites in four days, and then do revisions and fixes on the fifth. So to composite over 32 shots in four days meant finishing eight composites each day, which gave me one hour to complete each one. Of course some shots take longer than others, but that gives you an idea of the time spent to produce the finished result.

So this wasn’t a very big project, and I wasn’t working on it for very long, and yet it went very well and was a lot of fun.

Fun in the sun dark studio

I often think of this project as one of the most enjoyable I’ve ever worked on, and this was due to the team. I’d moved to Sydney in 2009 and I did a lot of work for Digital Pulse in 2010 with a group of guys that worked together really well. It’s funny how sometimes you get personalities that click together – if you don’t like your co-workers or you think your boss is a moron you can’t just download a plugin that makes them awesome.

It would be nice to think that you can update your clients as easily as you can update your software but unfortunately that’s not how the world works.

So in an industry where many people are freelance, and you find yourself being shuffled around and working with new people all the time, finding yourself at a company where there’s a good vibe isn’t something you should take for granted.

One of the more rewarding aspects of working in a small team is that it’s easy to share ideas and to feel involved in the end product. When working with large teams, and especially when multiple creatives are involved across multiple companies, it’s easy to feel as though you’re simply being hired to press buttons and not to have any sense of ownership with the final result. As I detailed in the 2nd project diary, one of the biggest factors in how much I enjoy a particular project is how involved I feel in the overall production. For this reason, I often find smaller projects more personally rewarding than large scale extravaganzas, even if the subject matter may not be that exciting.

As a small example, the opening shots of each video show a storm over a town. It occurred to me that as these videos were about electricity blackouts, we should see a lightning strike, but originally there wasn’t one in the storyboards. Initially the opening shot was shorter and even though a lightning strike only takes a few frames, the overall shot needed to be extended in order for the timing to feel right. However the audio had already been mixed – the voiceover had been recorded first and all of the animation was timed to the audio track. Extending the opening shot meant the soundtrack had to be remixed, and a sound effect added for the lightning. So it wasn’t as simple as just adding a solid and applying the ‘advanced lightning’ plugin. But it made sense, and the director was happy for me to add a lightning strike and to make the shot longer, and the audio track was adjusted accordingly.

This might seem like a little thing – perhaps even blatantly obvious – but it’s not. There wasn’t a lightning strike in the script or the storyboards and some of the other directors I’ve worked with would be extremely unhappy by the addition of elements outside of the brief. In different sectors of the industry it can be difficult to even talk to the director – and in the world of feature films it would be unheard of for a humble compositor to make suggestions about changing timing or adding new elements to a shot. So as simple as it might sound to add a lightning bolt to a scene, it’s an example of a healthy production environment.

There are places I’ve worked at where everyone sinks a little lower when the director walks into the office, and places where you look forward to having a beer with the director after work. The second one is where you want to be.

When I look at these videos now, even though they’re several years old, I’m still happy with the overall look, feel and atmosphere they have. Considering the time and budget constraints they were made under, the end result is much better than it could have been.

AE: Animating with both sides of the app

Apart from the pleasant work environment, the Ausgrid project is significant to me for a very different reason: this was the first project I worked on where I was specifically employed as a compositor, and my job was solely to composite together 3D passes.

These project diaries actually had their origin last year, when I began drafting an article called “AE: using both sides of the app”. It was going to be about the differences between motion graphics design and visual fx compositing, but I didn’t get far before realising the scope of the article was so large it would be better to make a series of articles with a common theme. This is the first in that series – but I still have the title image I made last year, so I’m going to use it so it doesn’t go to waste:

The next few project diaries will explore the theme that After Effects is an application with two sides – motion graphics and vfx compositing – and they’re really two very different things.

After Effects has a lot of features, it’s very powerful software that appeals to all sorts of people in many different industries. After Effects is synonymous with motion graphics, but it can also do visual fx, compositing, and more recently it’s expanding into character animation. These different capabilities are specialized areas in their own right, and motion graphics design is really quite different from visual fx compositing. However in the world of corporate production, many of the producers I’ve worked for just lump everything together under the broad heading of “After Effects”.

There are many software apps out there that are used by a wide range of industries. Photoshop, for example, is used for all sorts of different things. And Microsoft Word can do pretty much anything to do with text, from writing novels, to letters, to technical reports, to church newsletters and so on.

But if a marketing company is looking for someone to write press releases they don’t advertise for a Microsoft Word expert, if someone needs a logo designed they don’t advertise for a Photoshop expert, and if a council wants to build a bridge they don’t advertise for an AutoCAD expert . In other words, the software application that might be used is not what defines the job. Writing press releases is a marketing job, designing logos is a design job, and designing bridges is civil engineering. Even if there is an industry standard for the software used, the job is not defined by the software used to do it.

In this regard, the corporate video sector seems to be different – especially when it comes to After Effects. Nearly every producer and production company that I’ve worked for uses After Effects as the single solution for motion graphics, visual effects compositing, and occasionally character animation. And because After Effects can do all of these things, and it’s the industry standard for corporate video production, everything is just lumped together under the heading of ‘After Effects’ – even though title design requires a completely different set of skills to rotoscoping, and character animation has nothing in common with chromakeying.

This is a fairly personal observation, and it has a lot to do with how desktop video production has evolved over the past 20 years, but in 2016 it’s still the case for many of the companies I continue to work for (the series I made on the “desktop video revolution” actually started out as an introduction to an article on chromakeying. Brevity is not a gift I have been blessed with. But the series clearly demonstrates how After Effects has replaced multiple specialist companies)

So getting back to our current example- the Ausgrid series- it was unusual and refreshing to work with a team that acknowledged that compositing is a specific skill, and to employ me specifically as a compositor – even to the extent that the motion graphics elements were designed separately by the Director.

Now having just discussed the fact that motion graphics and compositing are really very different, the ironic thing about this being a compositing job was that there weren’t a lot of 3D passes to composite. The real challenge of this project was working within the very tight time constraints that we all had. The deadline was so tight that there simply wasn’t the time available to render out a whole bunch of exotic passes for each scene. But that’s why I talk about After Effects being an app with two sides. The feature-set of After Effects is so rich that I was able to create new elements using plugins, without having to rely on having the 3D guys provide me with all of the elements.

If you’re like me and you’ve mostly worked in the corporate sector then this might seem normal – but it stands in stark contrast to the way that visual fx are created on Hollywood films. In that world, compositing is purely compositing, with various passes and elements created by a seperate army of specialised artists. Particle effects, atmospheric effects and so one are all created by people whose job is to focus on those elements. The compositor’s job is to take them all and put them together – not to create them. Compared to the way Hollywood films work, the corporate approach with After Effects is quite different – because After Effects is generally used as the single solution for everything.

So the rewarding aspect of working on the Ausgrid project was taking the few elements that I had and creating a rich, atmospheric scene using the many different features of After Effects.

Examples – shot breakdowns

It’s difficult to open up old projects and resist the urge to tweak or even re-do everything again. It’s also difficult to remember what it was like even 6 years ago – software had fewer features, computers were slower and so on. When I look at the opening shot, for example, my first thought is that all of the lights would look better with lens flares – but this project was made before Video CoPilot’s Optical Flares had been released.

I’ve selected four shots to break down and demonstrate the way they were put together, and the techniques I used to embellish the scenes by creating additional elements in After Effects. Considering that I averaged one hour on each shot, I’ll always look at them and think of what I could do to make each scene even better – but every project has a budget and limits on resources, and I’m happy with what I was able to do in the time.

The first example is shot 5, as it was the first shot I worked on and it set the tone for all of the others. As the videos are about six years old, I’ll be quite honest and say that I really didn’t expect this shot to end up looking as good as it did. But the end result was so nice that I had to try an ensure all of the others matched it!

Shot 5: sparks and interactive lighting

Shot 22: windscreen wiper wash

Shot 01: lights, camera, lightning

Shot 08: mood lightning

Did you like this article? Have a look at some of my other ProVideo Coalition posts on After Effects.

If you are interested in compositing and visual fx, have a look at my tutorial on how to make really complex scenes in Particular, by creating z-depth mattes in After Effects.