When I started on the Xian project in 2011, it was the largest and most complex compositing project I had worked on. Even though about seven years have passed since then, I still think of it as some of the best work I’ve done – which isn’t usually the case with projects completed a long time ago. I’ve previously written about the Xian project so I won’t go into details about what it was, but basically it was a short film – albeit one made at a very high resolution and with multiple layers of projection. All of the sets were CG and the actors were shot against green screen, so the final film required extensive compositing. I can’t recall exactly, but I think the film had eight scenes and ran for just under half an hour. Compositing was split amongst five people: two of us (myself included) worked on two scenes each in After Effects, with another senior compositor completing two scenes in Nuke. Another two artists worked on a single scene each, also in After Effects.

The Xian project marked a number of significant milestones for me, and subsequently I’ve found it very difficult to produce a disciplined and structured project diary that maintains focus (I started writing this two years ago). Depending on how I count, this is either my forth or fifth attempt, and even then I’ve had to split it into two parts to keep it manageable. My first draft ran to a few thousand words before I even finished the introduction…

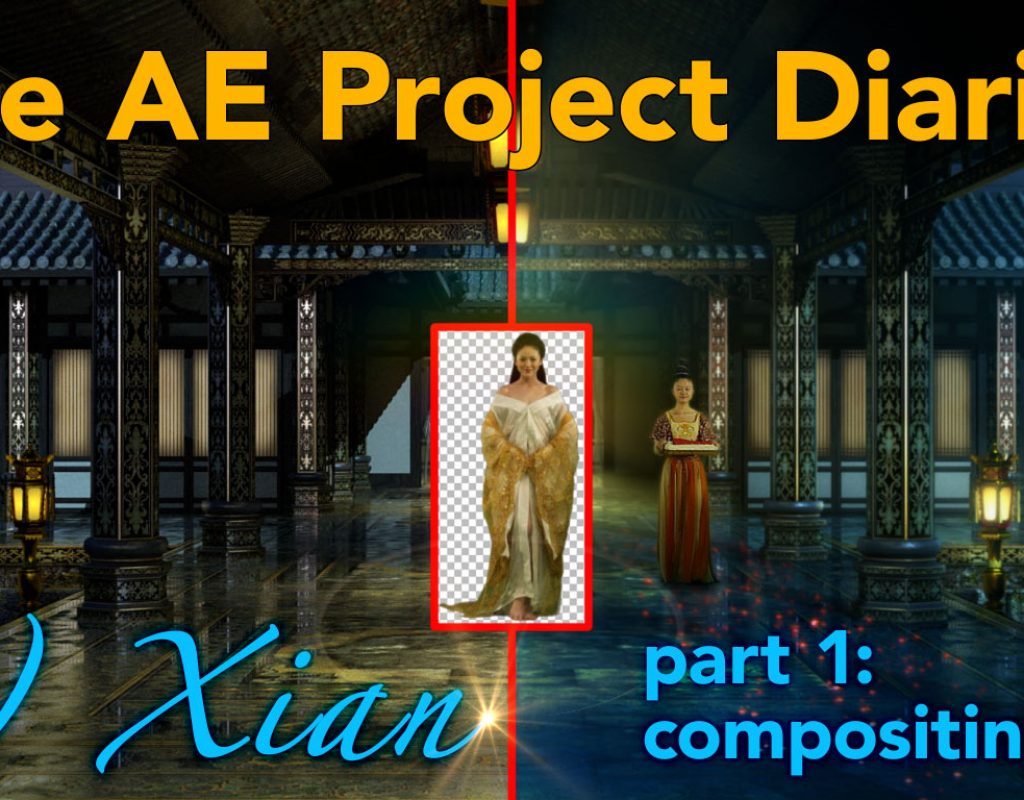

From a technical perspective, there are two main topics that I want to look at: compositing and colour grading. To keep things manageable I’ll be posting one diary on each topic, and this is the one on compositing.

From a personal perspective, the simple topics of “compositing” and “colour grading” lead to a wide range of more introspective thoughts – and ultimately I’m trying to cram 20 years of experience into a few cohesive paragraphs. But the point of project diaries is to share the personal stories behind the software, for anyone who’s ever wondered what it’s like to work somewhere else.

One recurring theme of mine is that (when I began my career) I found the technical aspects of the job easier to learn than the personal. Computers and software are logical, predictable, and generally well documented. People are not. It took me a long time to slowly learn that “The Industry” is not one big happy family, but rather a loose collection of smaller, separate industries that cater to different markets. I’ve written about this before but basically – the companies that do visual fx for Hollywood blockbusters are not the same companies that make YouTube videos showing how to use your new espresso machine. They are not better or worse, just different: different markets, different clients, different economies, different workflows, different cultures and to be brutally honest: completely different worlds.

As an After Effects freelancer, moving between different companies that cater to different clients, one of the skills I needed to develop was being able to gauge the level of “quality” expected of each new project, and being able to fit in with the time and budget that was allocated. I’ve worked at companies where an entire project might have a budget of a few hours. I’ve also worked at companies where they can spend a week just choosing a font. I’m not exaggerating when I say that different companies can give you projects with basically the same brief, except the budgets can be different by a factor of ten – or even more. Simply learning that different companies have different budgets and different expectations took me years – it’s still the case today – and it’s so significant that it’s something I’ve touched on in previous articles.

An earlier project diary looked at the Ausgrid production, a small corporate video that was destined for YouTube. It was made by four people in two weeks, on a very low budget. Just producing 6 minutes of 3D animation in two weeks was challenging (and impressive) enough. As I detailed in the Ausgrid project diary, I initially had about 32 shots to composite in 4 days – which worked out at roughly 1 shot per hour. In a very general sense, the overall “quality” of the project was determined by the assets provided and what I could do with them in a short time.

There’s an old saying about how to assume something makes an ass out of you and me. One aspect of the Xian project that I think about a lot is how the early assumptions I made were wrong. When I first started working on Xian, I totally underestimated the level of quality expected. In retrospect this wasn’t entirely my fault, but those details are too boring to share. The simple version is that I was at a studio working on a different project, and I was pulled off to help out on Xian. I had no real idea of what the Xian project was, but I inherited an existing After Effects project from someone else, and I had to composite about 50 shots in 3 days. Despite the fact that the working resolution was so large (6172 x 1080), completing 50 shots in about 3 days meant I only had about ½ hour for each one – less time than the low budget Ausgrid project which was rendered at 1024 x 512!

Initially I was alarmed at how much work had to be done (our deadline ended up being extended by a few days), but I saw that a bunch of shots had been marked as “complete”, and they were pretty rough. There was also a scene which had been marked as finished, which was entirely 3D rendered and had been supplied by a different company. It looked dreadful – I remember commenting that the graphics looked worse than a game on the Nintendo Wii – but as it was marked as done I assumed it was an indication of the “quality” that was acceptable.

So in summary – I was pulled off a different project to help meet a tight deadline, I didn’t really know anything about what I was working on except that I had a lot of work to do in a short period of time, and some shots that had been marked as finished were pretty bad. This lead me to the assumption that it was a low-quality, low-budget production that just needed to be completed as quickly as possible. As it turned out, those assumptions were all wrong (and eventually the scene that I thought looked like a Wii game was completely re-made).

With the benefit of a few years more experience, I now suspect that the initial deadline was to meet some sort of contractual obligation relating to the first rough cut. This is just a guess, but after those of us in the studio managed to scrape something together for the first deadline, we ended up working on the project for another few months. Once I realized that I would be working on Xian for the foreseeable future, and not just 3 days, I needed to completely re-think my approach and adjust my workflow accordingly.

The video component of this project diary looks at the difference in scale between the Ausgrid project and the Xian project, and demonstrates how it’s possible for a single shot to take over a week to composite, but there are a couple of other aspects of the project that I wanted to share.

Every After Effects user has their own way of working and organizing projects, and working in an After Effects project that is organized differently to your own preference can slow you down and generally make you feel clumsy. Initially, I thought I was only helping out for a few days, so I felt obliged to continue working in the same way that the original AE project had been made. Once I realized that I would be working on Xian for a longer time, I decided that I was going to restructure everything and work in the way that I usually would. At the time, this was a significant decision but one that made my life much happier – but it also meant that I spent at least half a day just cleaning up the project and not doing any actual “work”.

I mentioned above that this project marked a number of milestones for me, and some of them were specifically related to how I approach compositing in After Effects. Before Xian, the exact way that I built up compositions would vary a bit from project to project– I wouldn’t say that I had a perfectly consistent approach. But Xian was so complex that I decided I was going to establish a consistent workflow and stick to it – not just for Xian but also for all future jobs. While it was too late in the year for them to be New Years resolutions, I devised four commandments that I’ve continued to obey ever since:

- Thou shalt organize all After Effects projects in the same way

- Thou shalt always use consistent colour labels

- Thou shalt always pre-compose all mattes

- Thou shalt always use the Set Matte effect, and not track mattes

It’s not that I wasn’t already doing this. I’ve always prided myself on having clearly organised projects, I generally used colour labels, and I knew the Set Matte effect had advantages over track mattes. But the Xian project marked the point where I decided I was going to take things seriously, and to define a bunch of rules for myself and follow them for all future jobs. These rules might not seem that significant, but they represent a sort of personal philosophy regarding compositing in After Effects. It’s not so much the rules themselves which are special, but it’s the fact that I ALWAYS follow them CONSISTENTLY.

Organisation.

The first commandment, about always structuring projects the same way, is something I’ve been doing almost since I started using After Effects. While it might give the impression that I’m an organised person it really just comes down to me having a poor memory. After a few years of opening up old After Effects projects and having no idea what was going on, I realised I had no-one to blame except myself. It occurred to me that if I came up with a consistent project structure then it wouldn’t matter whether or not I could remember creating the project in the first place – I’d still be able to figure out what was going in. While it probably isn’t interesting to read an article about how I name my folders, the point is that I can open up a project that I don’t remember working on, and I know where everything is. Do you need to see a screenshot of a well-named folder? I’m guessing not.

Colour Labels.

The second commandment – using colour labels – is also widely recommended but beyond being good practice, there’s also a useful workflow tip that not all users are aware of. After Effects allows you to select all the layers in a comp that have the same colour label, just by right-clicking on the colour label icon and choosing “select label group”.

This is incredibly useful and it’s a shame the feature is often overlooked. As an example, let’s imagine a composition has lots of text layers, and you’re asked to change the font. If all of the text layers have the same unique label colour, then instead of manually clicking on each individual layer, just right-click on one and choose “select label group”. All of the text layers are now selected, and you can change the font of every text layer simultaneously.

While I had used colour labels to symbollically group layers in my compositions, I tended to make up the way I used different colours as I went along. With Xian, I resolved to use the same label colours in the same way, consistently and for all future projects. Most of the colour labels I decided on for Xian are still the ones I always use today. My adjustment layers are always yellow, audio is always fuschia, any layers that don’t need to be visible are set to “none”. I can open up a project from years ago and just by glancing at the timeline, I can tell from the colours what is going on.

With Xian, I also used colour labels to denote different sections of the composite. For example, I used one colour for the background matte painting, another for the foreground 3D, another for any live action footage, and another for atmospheric effects and so on. This made it easy to isolate specific elements that I wanted to focus on when working.

Another tip that can help on larger projects is to add null objects into your timeline, and apply markers with notes on what you’ve done. Even simple notes like “all layers below here are matte painting”, or “all orange layers are particle renders from Houdini” can help you understand a project if you have to open it up again at a later date.

Pre-Compose all mattes.

Deciding to always pre-compose all mattes is something I haven’t seen anyone else do, and it’s more to do with consistency than one specific example. The original reasoning behind this decision was to do with the complexity of the 3D assets being provided for Xian, and the use of RGB multimattes. If you haven’t come across these before, then it’s common for 3D artists to combine multiple mattes from a scene into one render, with individual mattes being coloured red, green and blue. Different people call these different things – ID mattes, puzzle mattes and multimattes are the most common terms I’ve come across. A basic RGB matte can combine 3 individual mattes into one render, but it’s also possible to use black and white too, to combine 5 mattes in a single file. Once you import a multimatte render into After Effects, you can use an effect like “shift channels” or “set matte” to isolate the channel you need.

For simple composites, the most common approach is to use the multimatte file as an alpha track matte, with the set matte or shift channel effect applied. The problem is when you want to combine more than one matte, or use certain masks and effects, or otherwise manipulate the matte. After Effects only allows you to have one track matte per layer and it’s pretty easy to run into the limitations of only working with a single layer.

The 3D sets and assets being rendered for Xian were complex, and often the exact matte needed for a compositing effect required a combination of several different matte files. As this couldn’t be done simply in a single layer, the mattes needed to be pre-composed. Pre-composing a matte has a few advantages. Firstly, once you have an entire composition dedicated to a matte then you are freed from the restrictions of working with a single layer. You can add adjustment layers, you can even use track mattes with the original matte – useful if you want a simple mask to feather edges, for example. Secondly, many of the mattes I was setting up were used multiple times, so pre-composing them makes rendering faster. Finally, by pre-composing mattes they can also be used as adjustment layers – which is very powerful and useful.

Another reason that I decided to pre-compose all my mattes was to do with size. Because the working resolution of the Xian project was so high (6172 x 1080), many of the 3D renders were done at a lower resolution and then scaled up in After Effects. The size the renders were done at could vary a bit depending on how busy the render farm was, the type of shot, and even how quickly it was needed. Subsequently the 3D renders were a mixture of different resolutions – it wouldn’t be unusual for a beauty pass to be 75% of the final size but for the mattes to be full resolution. Fog or particles may be 50%. Pre-composing all of the 3D renders and scaling them up helped to avoid problems in After Effects caused by layers being different sizes and scales.

Once I realized that many mattes needed to be pre-composed, I decided that I was going to pre-compose ALL of them for consistency. Even though this might sound unnecessary, it has one important benefit which is purely psychological: if a matte is already pre-comped, then it’s easier to jump into the precomp and refine or experiment with it. Because I’m struggling to think of an example, let me re-phrase this another way: it stops you being lazy. If you composite by using a source layer as a track matte, there may be things you want to try but would require the matte to be pre-comped. So maybe you don’t bother trying it. But if ALL your mattes are ALWAYS precomps, then there’s no excuse – it’s easy to just play around a bit, free from the limitations of being a single layer. It’s more significant than it sounds, and I guess that the decision to pre-compose all mattes is as much psychological as it is technical. But don’t knock it ’til you’ve tried it, and pre-composing mattes also helps with my final resolution: NO TRACK MATTES.

No Track Mattes.

Even though I use them when I have to, I hate track mattes. Yes they are simple to use, intuitive, and a fundamental part of After Effects but I avoid them whenever I can. The simple reason I hate them is because their visibility is turned off, and if you have lots of layers with lots of track mattes then it’s difficult to keep track of which layers need to be turned on and which ones don’t. It’s pretty common for large complex projects to have lots of layers – the composites in Xian had well over 100 layers in them and many of them referenced a matte of some sort. When working on a composite, it’s normal to want to turn groups of layers on and off, but this is a PITA if every second layer is a track matte.

By using the “set matte” effect instead, it makes it possible to “hide” all of the matte layers down the bottom of the timeline, out of the way. By using the “set matte” effect to reference the layers, there’s no track matte layer taking up space above them. It’s simple but very effective. It makes the timeline more compact, easier to understand, and saves a whole bunch of clicking.

In one way or another, I’d respected those four rules well before the Xian project. But the sheer scale of Xian – not just the technical resolution of the project but the timeframe and attention to detail – lead me to adopt a more structured and consistent approach to the way I worked. I have faithfully followed those four simple compositing commandments ever since, and working so consistently has definitely improved my long-term productivity.

The video above takes you through some of the larger shots I worked on, and gives an overview of what was involved in building up the composites. Beyond the compositing was another fundamental stage – colour grading, and that’s what we will look at in part 2.

Footnote: In the video I mention that I was going to discuss something about the camera and nulls exported from 3D Studio Max to After Effects. While I edited that bit out because it got a bit long and I didn’t have any video to show for it, I’ll elaborate here. The 3D artists were using 3D Studio Max, and they had a script which would export camera data and location nulls from Max to AE. Generally this worked fine, but for the opening two shots I noticed that the world size was huge. The distance between the left and right sides of the scene was roughly 100,000 pixels in After Effects terms. Because everyone was so busy, I didn’t want to bug the 3D guys and ask if there was any way of scaling down the export (turns out there was), and anyway – everything worked. All of the nulls lined up with the 3D renders and After Effects doesn’t mind if you have a layer 100,000 pixels away. But as I mention in the video, I was using Trapcode Particular and Form to add rose petals to the scene, and I noticed that the particles disappeared at certain points. After a bit of experimenting I discovered that Trapcode plugins have a maximum world size of 32,768 pixels – which is usually fine if you’re making corporate infographics for YouTube. It’s possible I was one of the first people to find that a problem. As the scene had already been built at that size, I just used multiple instances of the plugins with the location of the particles overlapping to look seamless.

Made it this far? Check out Part 2 here! And I’ve got plenty more articles at the ProVideo Coalition…