Obsessed with movies and lighting, a photography course set the path Andrew Shulkind would walk. Virtual Reality came after, and while it expands the way to tell stories, Andrew believes we’ve to watch so we don’t corrupt our legacy of storytelling.

The International Cinematographers Guild recognized Andrew Shulkind as one of the top emerging cinematographers in 2013, and in 2014 he received the Studio Daily Prime Award, a distinction reserved for manufacturers leading technological innovation in the world of film. His passion for Virtual Reality, and the involvement with the development of VR and mixed reality camera solutions explain why he was the first individual to receive the award.

Andrew Shulkind is a director of virtual reality cinematography at Headcase, a 360° virtual reality content studio. Comprised of a world-class team of producers, directors, innovators, creators and dreamers, the company produces premium, live-action virtual reality experiences using its proprietary technology. They’ve joined to create Headcase, because they believe that virtual reality is the next evolution in telling stories and communicating ideas.

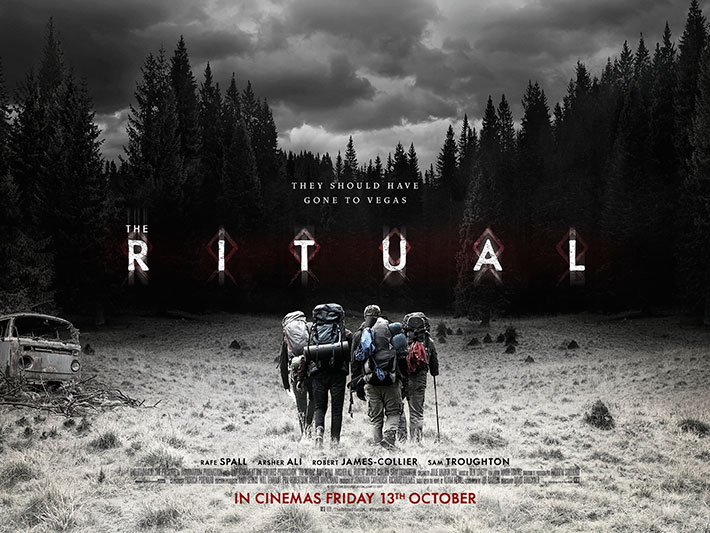

Andrew is an explorer by heart, always eager to look beyond the horizon. VR in all its variants, new forms of acquisition such as volumetric capture and light field photography, interest him, but that has not kept him away from shooting traditional projects where he can refine his use of classic filmmaking tools, and explore light in every imaginable way. A recent project for Netflix, the horror movie The Ritual, gave him the ideal background to accept new challenges and take his passion for lighting techniques to new heights.

https://youtu.be/Vfugwq2uoa0

The Ritual seemed to be a good starting point to ask Andrew Shulkind a few questions, and with the help from Catie Disabato, from communications firm Sunshine Sachs, I prepared this written interview, which follows an interview project I did, years ago, with different photographers, from David duChemin to Clay Bolt, Guy Tal, Ian Plant, Niall Benvie or Ibarionex Perello. While some people prefer live interviews, I believe, after having done many of those, a written interview has some advantages, especially if you’re not doing hard news, and want to portray someone the best way you can. A written interview gives the interviewee time to define what is the best answer, and if you’ve prepared a good set of questions you’ll probably get answers that will create a lively, interesting interview. As I believe this one, with Andrew Shulkind, is. So, having said this, let’s continue.

Going away from the VR, AR and MR experiences that have marked his path in recent years, Andrew Shulkind still continues to immerse viewers into a story, through the ways he captures action for the horror movie The Ritual, which was released to Netflix on February 9, this year. Here it is all about old school techniques with a lot of exploration in lighting, to better “paint” the mood of the story.

Compared, by some, to The Blair Witch Project, The Ritual may have some common points, but it’s a different story altogether. The Ritual is a 2017 British horror film directed by David Bruckner and written by Joe Barton. Based on Adam Nevill’s award-winning novel, the film follows the adventure lived by a group of college friends travelling through a dark forest above the Arctic Circle in northern Sweden. The “Swedish forest, though, was recreated in Romania wilderness, where the crew spent some six weeks filming inside a forest, to capture the core images for the psychological drama The Ritual.

Filming inside a forest in a remote location was a challenging endeavor at all levels, starting with the choice of cameras and lighting. That’s where this interview, starts, with DP Andrew Shulkind explaining the choices made.

ProVideo Coalition – Your recent project, The Ritual, was shot in Romania in conditions that made it essential to choose the cameras used to capture the footage. You’ve chosen Canon Cinema EOS C700 and a C300 Mark II. Can you explain how the choice was made and the reasons for picking those cameras?

Andrew Shulkind – Prior to The Ritual, I had shot another movie with a pair of Canon C300 Mark IIs. We had gone through an exhaustive testing process to confirm for ourselves and demonstrate to the producers that the cameras could match up to ARRI Alexa and RED Dragon (at the time), in terms of bit depth, dynamic range, physical reliability, and recording options. In fact, on that movie (called The Vault), we found that not only did the Canon C300 Mark II match up with those other cameras, the extraordinary Canon sensor could in some cases outperform them. We found that, in certain circumstances, we could rate the C300Mark II and C700 to give us an extra stop and sometimes as much as three stops more light (with a totally acceptable noise floor) as with Alexa and RED. That half to a quarter of the light needed!

Andrew Shulkind – It’s true, we had some rather severe conditions on this movie. Four weeks of night shoots at 8000’ on steep mountain slopes in a remote location, extreme temperatures, an unexpected snowstorm in the middle of our schedule, company moves each day with long cable runs definitely put every department to the test.

I went in with the primary goal of using the magic of these highly sensitive sensors artfully, utilizing the nuance of soft shadows at the bottom end of the curve. Many of the scenes take place with little to no motivated light and David Bruckner and I wanted to represent the darkness of the Scandinavian night in an authentic way but not miss performance and character details. As fantastical and supernatural as the plot becomes by the end, we wanted a naturalistic look.

So often people talk about using highly sensitive sensors to get out of a jam or resolve a surprise problem, but I wanted to use that technical advantage creatively. Shooting with so little light doesn’t mean not lighting it, quite the opposite. In fact, we had two 100’ construction cranes with several lighting balloons that we would maneuver around our exterior night locations, plus our package that we lit from the ground. And it allowed my gaffer, Florin Niculae, and I to paint with delicate strokes around the set with surgical detail. And allowed me to use LEDs very dimmed down in the background to create depth, which I could power with batteries to save our electrics the setup and wrap out time of even crazier cable runs than we had!

One thing that we discovered over the course of shooting was that we were up against such extreme physical demands in photographing these stunning locations that it became extra incumbent on us to have viewer feel that same challenge that our characters were actually up against, so that the severity of our physical experience wasn’t lost to the process and could end up on screen in a visual way.

PVC – In terms of tools, besides cameras and lenses, what can, usually, be found inside your tool bag?

Andrew Shulkind – Definitely a daylight visible laser pointer. It always feels a little imperious to use, but I can be hyper specific in communicating with my crew and always saves us time.

Also they say the best tools are the ones that you have on you. I always have my iPhone on me, so I’m constantly relying on Nic Sadler’s Artemis app and one of several sun locating AR apps. I love my director’s viewfinders, but ever since we moved from shooting film on a fixed film dimension, the sensor size has become inconsistent. Not just in terms of resolution, but the actual sensor dimensions vary, so lenses render differently. The lens field of view is dictate by the proportional relationship to the sensor, so a 35mm lens won’t appear the same scale across different sensor sizes. This is where Artemis comes in. By specifying your lens and exact camera specs, you can generate the exact field of view with your phone’s camera (limited only by the widest angle of that lens).

Unfortunately, the sun tracking apps aren’t as accurate. It’s common for the GPS in everyone’s phone to position the sun a little differently, which can be a problem if you’re trying to estimate when the sun comes through a window. There isn’t yet as reliable a replacement for my exactitude of my trusty Suunto and Sunpath.

PVC – You talk a lot about games, how they offer features, like interactivity and roaming freedom that films should be able to use. You also mention, many times, that we may see, in the future, the same property being distributed in different versions, more story-driven, more gaming-driven or more interactive-driven. Do you play games? Which?

Andrew Shulkind – That’s right. I am engaged a lot with the cinemafication of games and the gamification of movies. So I play as many games as I can get my hands on (and have time for). I have a PS4 and I’m loving the new God of War. In this version, the whole game is a one-take. I like GTA and Uncharted and Red Dead Redemption that I used to play on Xbox. I’m a total sucker for puzzle games and love Moss on PS.

PVC – Do you also get inspiration from games you play or watch and carry it into your work?

Andrew Shulkind – Absolutely.

PVC – You’ve started your career as a Kodak/Panavision PreView System technician and moved quickly through the industry, from camera assistant to camera operator and DP. Those multiple experiences are reflected on how you’re seen by the industry: as someone able to seamless integrate visual effects and innovative technologies, and also as a specialist when it comes to the use of lighting. Did you, as a child, already dream about all those things and how you could use them for storytelling?

Andrew Shulkind – I was always interested in movies and games and saw an inherent connection between them. Also, I was interested in radios and electronics, so I really liked the mechanical aspect of cameras. Non-linear editing arrived while I was in film school and NYU got their first digital cameras (the Canon XL1) when I was in my third year. So I felt comfortable with both exposing film and photochemical finishing as well as working with video files and emulating a polished look on those young digital formats. With that cinematic heritage and as imaging has become digitally driven, I feel a responsibility to help preserve the technical and creative strides that others forged photochemically in the future of imaging.

PVC – How did you discover you wanted to be a filmmaker? How do you describe who you are and what you do?

Andrew Shulkind – Growing up, I was obsessed with movies and lighting, but was more into tinkering, I always thought that I’d be a broadcaster or an announcer. It wasn’t until college, when I took a proper course in photography, that I fell in love with the psychology of images.

But after building a super high resolution 32K spherical camera array for some early VR capture, I’ve found myself deep down the immersive path, both shooting and helping to explore the future of virtual cinematography, the interactive future of imaging, and consulting with tech companies, studios, brands, sports leagues, and manufacturers to envision the future of entertainment content itself.

PVC – Who’s inspired your career? What do you do to find inspiration?

Andrew Shulkind – I was extremely lucky to fall in with Janusz Kaminski’s camera team straight out of film school and began working under their generous tutelage on movies with Steven Spielberg. Coming up on movies with Steven and Michael Mann, David Fincher, and Jerry Bruckheimer, I was literally exposed to the best in the business and I soaked up as much as I could. I learned the magic of lighting from Janusz and Darius Khondji , how to move the camera from Don Burgess and Guillermo Navarro. I was inspired and mentored not only by these DPs at the top of their game, but also production designers, visual effects supervisors and the best directors in doing what they do.

But I find inspiration in just about anything, I think truth and nuance are what make cinema such a seductive medium and I can be as inspired by a great performance and beautiful lighting as I am by a beam of sunlight sliding through a pine grove or my kids shaky iPhone video from a low perspective.

PVC – Director Martina Buckley, with whom you’ve worked, refers to you as “the Brain Box” and is quoted in one article at Studio Daily as saying: “He really is interested in mixing new technologies with the old out of passion for his craft and a genuine pursuit of what is best looking and the most appropriate tool for telling the story. But he’s not a fashion victim; he has his own ideas about how he wants to use new technology.” Is that passion for technology the reason why you’ve invested in VR and created a company, Headcase?

Andrew Shulkind – Haha… Martina is one of my favorite people and she is very generous. Whether it’s my involvement with Headcase or Google or Oculus or Centiment.io or any of the other organizations that I’m involved with, I think we have to continue to innovate or be eaten by technology.

PVC – Where do you go from here, in professional terms?

Andrew Shulkind – We are on the verge of a dramatic paradigm shift in how we photograph and how audiences experience cinematic content. The Cinematographer (and often VFX supervisor) are really the CTOs of the movie. Emerging technology can afford so many advantages and efficiencies to productions of all sizes and it our responsibility as filmmakers to explore and realize those benefits responsibly. With that in mind, I am quite concerned about quality in the immersive space, on nuance in interactive experiences and an all-CG future because it’s easier to render than live action volumetric assets. I think that data poses significant benefits to our filmmaking workflow, but so many of those efficiencies can compromise the creative process if not carefully shepherded.

With the digital revolution, the traditional role of the Cinematographer has been frayed into several different processes, required new forms of communication and workarounds to ensure that we are still doing our jobs, whether that be color correction with detailed windows and secondaries, reframing for composition, or relighting a scene in a game engine, much of the production process is now part of post, and much of the post process and visual effects stages have been brought forward into production. To preserve the collective authorship from principal photography with the director and to retain the merit of the overall big picture, it requires an adaptable process; and in some ways, perhaps it always has.

But if we aren’t careful, the intersection of the content business and the data business can corrupt our legacy of storytelling. I hope to help shape out imaging 2.0, utilizing machine learning and creative AI to create smart efficiencies, modeling where and when real people need to touch the process, ensure that the cinematic characteristics that we’ve honed over the past hundred years remains as relevant as ever before. Because those human stories are our job and our lifeblood.