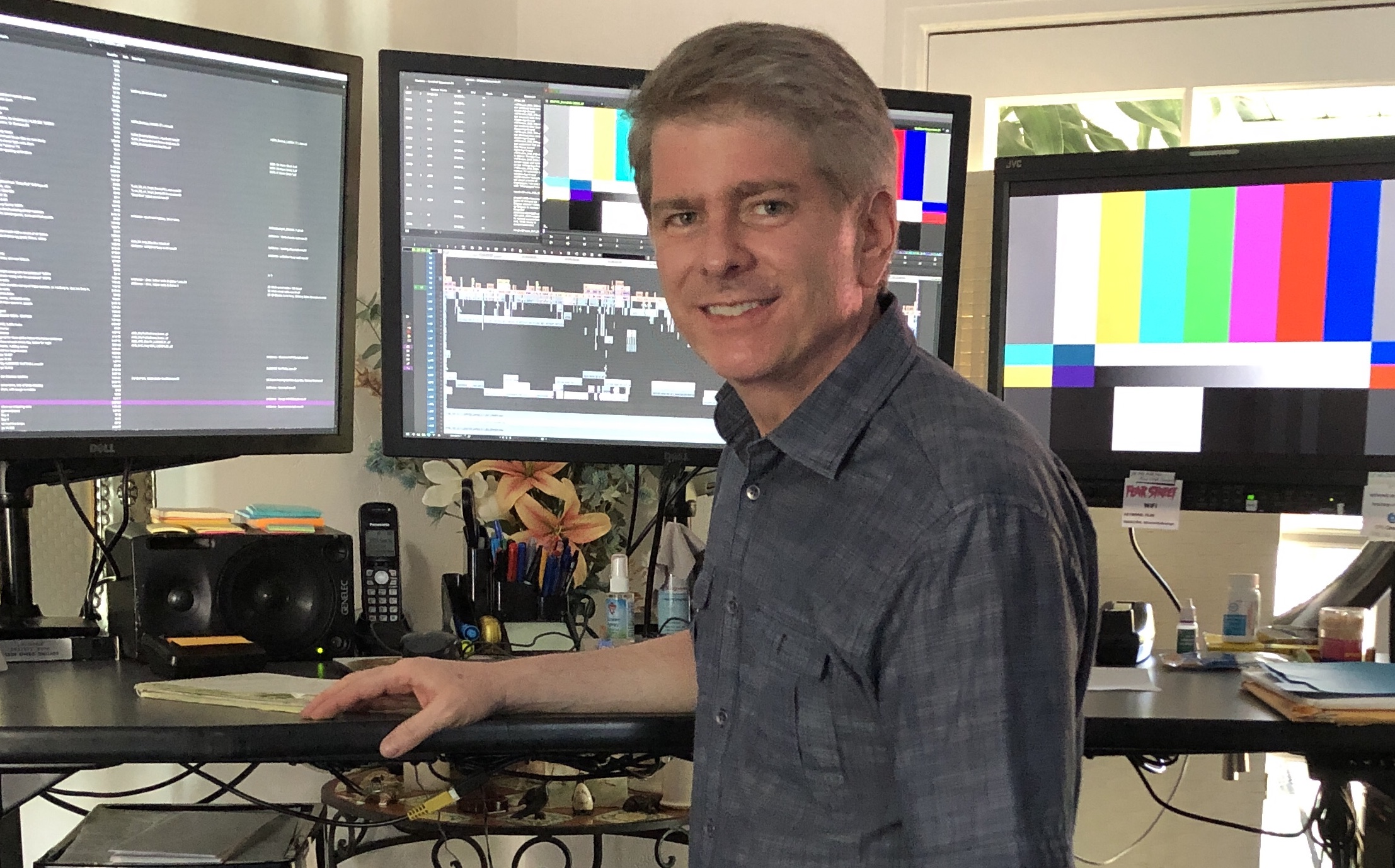

Today, we’re talking about the feature film Antebellum with editor John Axelrad, ACE.

I’ve interviewed John before for his films Ad Astra and The Lost City of Z.

John’s other work includes Papillon, Krampus, Crazy Heart and We Own the Night, among many others.

Also with us is John’s assistant editor on Antebellum, Jared Simon. Jared has worked on Ad Astra and The New Mutants as well as working as assistant editor on the pilot of the TV series, New Amsterdam.

This interview is available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: Congratulations on a great movie. Thank you both for being here. If you would — starting with John — could you introduce yourself so the people who are listening instead of watching, can understand whose voice belongs to whom.

AXELRAD: I am John Axelrad. I am the editor of Antebellum. I’ve been editing for the last 20 years. I started off as an assistant editor in this great industry. I learned from some of the best like Donn Cambern and Anne V. Coates.

I took the baton and have been editing pretty steadily for many years. So I’m very fortunate.

SIMON: And I’m Jared Simon. I was the first assistant editor on Antebellum. I had worked with John first on Ad Astra and before that with Matthew Rundell and Robb Sullivan.

HULLFISH: It’s really great having you both here. John, you’ve invited Jared to join us today — which I thought was a fantastic thing. I love that we’re talking with him as well.

What is the reason why you wanted him on this call?

AXELRAD: I’ve always maintained that editing is a team effort. My editing room — and I’m sure Jared can attest — I like to just have a very open collaborative environment. I adore my assistants. I know they work extremely hard and I want to be able to reward them by having them involved creatively in the process. My past assistants include Tom Cross. I think he’s done very well.

HULLFISH: He’s done pretty well for himself.

AXELRAD: He was my assistant on five movies and he got additional editing credit and all of them. It was still a little early in my career. I started sharing editing credit with Kayla Emter. She edited with me on The Immigrants and the Don Cheadle-Miles Davis movie, Miles Ahead.

She’s done very well. Last year she edited Hustlers.

And then Lee Haugen was my assistant and we’ve collaborated on a couple of films including The Lost City of Z and Ad Astra.

I met Jared through Robb Sullivan and this is my first time with Jared as my first assistant. Before it was Scott Morris who has been a great collaborator and he wound up getting additional editing credit on Ad Astra.

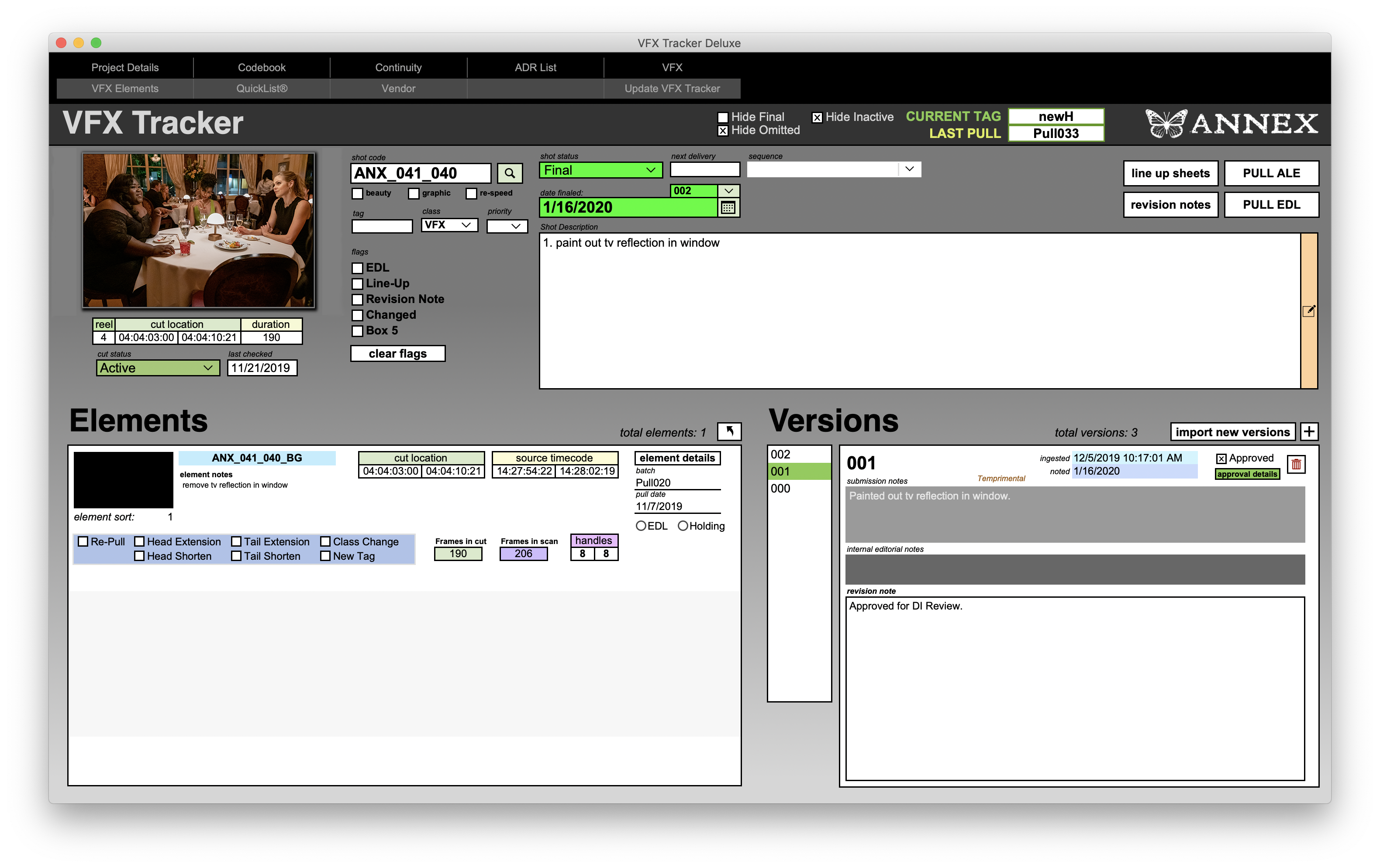

But Ad Astra was a film that just went on and on and so Scott couldn’t join me on Antebellum. Jared stepped in and Jared did a fantastic job. He was very creative when it came to visual effects temping. He did most of the temping of our visual effects but also narratively — I gave them scenes to edit. I really valued his input as did the directors.

HULLFISH: Was there anything special in this, Jared, workflow-wise that was challenging or different from previous films you’d worked on?

SIMON: There wasn’t anything that was specific or different about this. It really cemented a lot of the practices that I had learned on previous films, especially working on Ad Astra.

Because of the environment that John fosters in the room — and John and Lee had an Ad Astra — Scott was really busy but he was afforded a lot of time to teach me the best practices of how to step into the first assistant seat and what that would look like.

So I wouldn’t say that there was an extraordinarily different, but I was prepared because of my experiences on that film and on The New Mutants where I was hanging out with the first assistant on that for a lot of my time and just being exposed to what the responsibilities are and what to expect — that way I can be proactive and prepare for things down the line.

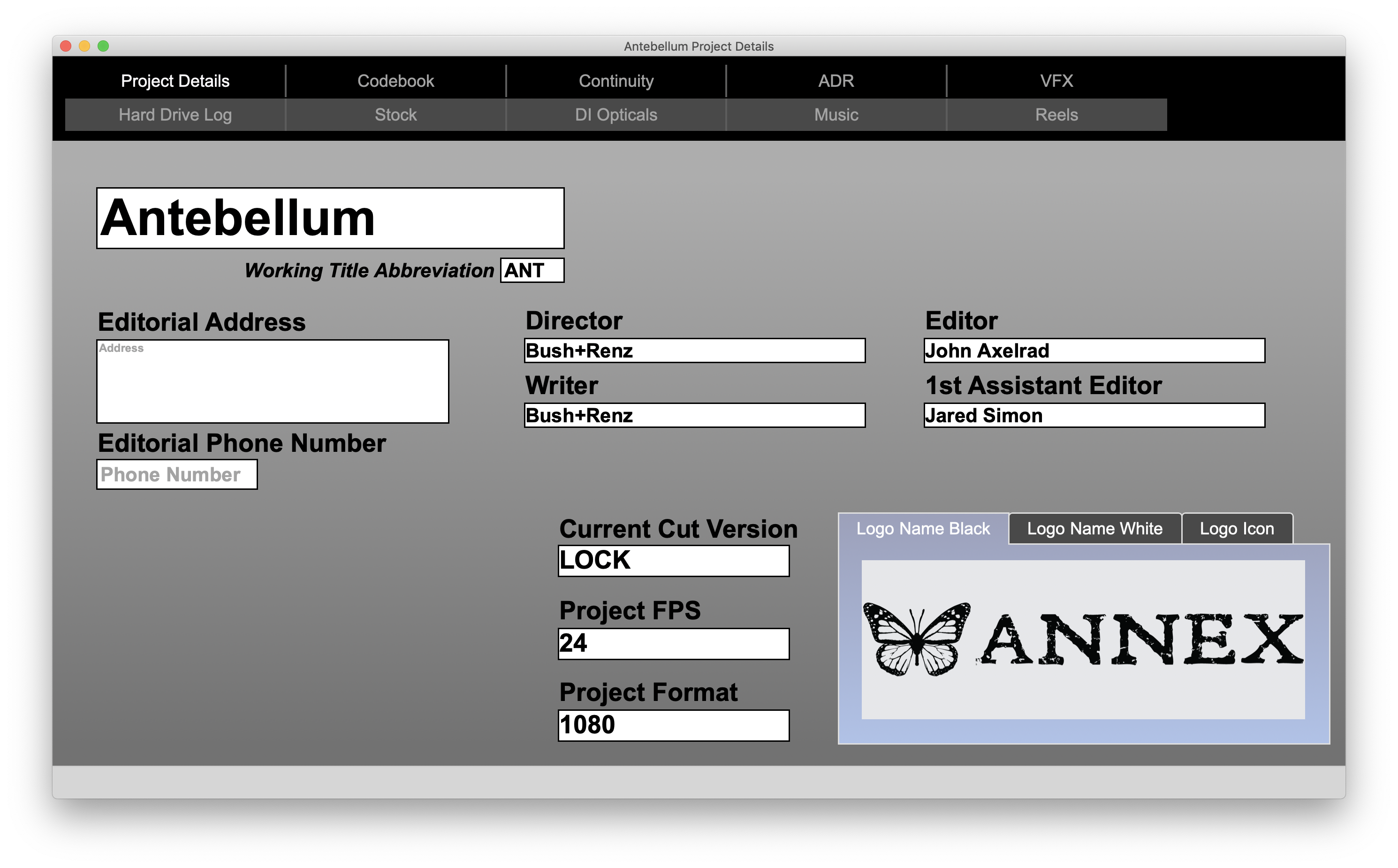

I built a database on this show based on the structure that I clung to that John provided. Things like marker systems, marker formatting, versioning cuts. There was a lot that I built on upon.

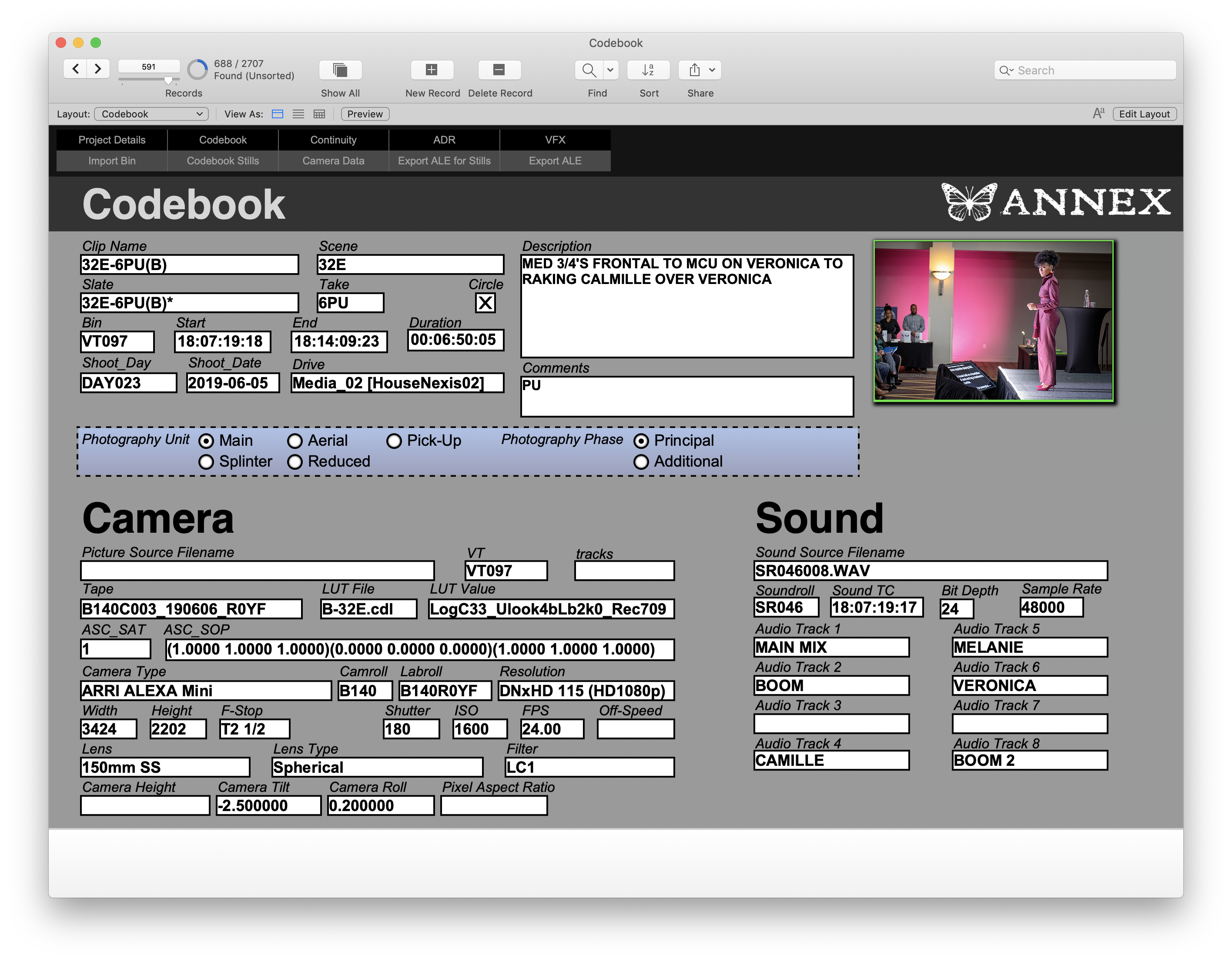

HULLFISH: I really want to get to the editing with John — and with you — but I am really interested in the database that you built. I’m assuming this is FilemakerPro and this would be what is called a codebook. Can you speak to what the importance of it is and what are some of the things that are in a codebook and why do you need them?

SIMON: A great resource that’s out there is Richard Sanchez’s Master the Workflow course, where he talks a great deal about his codebook.

HULLFISH: Absolutely.

AXELRAD: That was on my periphery. I had read a lot of blog posts, like Evan Schiff’s editing brain dump. A lot of it is VFX databases. I started teaching myself Filemaker and I saw that it was much more powerful than even how I’m currently using it. It’s still evolving.

The crux of it is the code book which is really just a repository for all of the dailies data that comes in. So when we were getting dailies in, I’d spoken with the dailies tech. I’d made sure that he was putting the right information in bins and making sure that we had specific information that was coming through — his comments were coming through in the bin.

I had a bin view that I would export and bring that into Filemaker and that would allow me later on down the line — when we were doing VFX turnovers — to have information that was coming in through EDLs from our timeline that was fed into a different portion of the database.

It would pull from the code book and it would give me all this information like lens data and — there’s so much that the database does that I’m having trouble, because it’s more than just VFX. Also I used it for ADR. I used it to track our ADR lines. I used it for our continuity formatting — to time the continuity as well. I used it to keep track of our DI and our optical effects. I used to keep track of our music cue sheet.

We had a music editor — Anele Onyekwere — who was working down the hall from us and he saw what I was doing with the VFX, just keeping track of that, and he was showing me what he was doing in ProTools. Because I taught myself Filemaker I was able to build a whole portion of my database that he could access through a secure wireless connection and he was able to feed ProTools documents into the database and it would do the math for him to do his timing on the cues.

That would save him time and that also gave me insight as to what cues are we using in the movie? What version of the cues are we using? What’s currently in there? He also had access to our continuity so he could see what scenes his cues were in. So it was a really great way to bring the whole team together.

It wasn’t just me using the database. It was also our second assistant editors who were working on the movie that we’re able to tap in and do a lot of logging and description.

HULLFISH: John, for you as an editor, is that database something that’s just invisible and you don’t really worry about it — other than the fact that it makes things go smoothly behind the scenes — or is it something that you’re actually taking advantage of?

AXELRAD: Well, I only take advantage of it insomuch that I really dot my i’s and cross my T’s when it comes to markers — formerly known as locators — in Avid. I am very fastidious with ADR — marking ADR lines — specifically exactly where they should go.

I developed this format with Tom Cross where it’s tab-delimited with equal signs that separate the different fields. So I do that with VFX, with DI effects, ADR. It was important to me that nothing got missed.

So when I saw Jared’s database I knew that he was properly going to handle all this incoming information. It wasn’t just something thrown on a Microsoft Word document. It was processed and everything was being tracked.

So it just made me sleep better at night. I wasn’t necessarily working with his database, but seeing what he was doing with it made all the difference to me.

SIMON: Dealing with versioning cuts was part of that peace-of-mind. The way that John likes to work is with these work-in-progress cuts. With the database, I kept track of what version of the cut went out to which department when and I could recall at a moment’s notice: what’s the last turn-over the music department got as opposed to the composer? And I kept records of that stuff because a lot of the versioning would fall to me.

I would take the work-in-progress and assign it a version based on the last turnover. It was the peace-of-mind of knowing that everything is accounted for and everything is being taken care of.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk a little bit about story and structure and that kind of thing. This is an interesting movie. From the trailer, I think everybody knows that it kind of occurs in two different time periods: present-day and what appears to be the past.

What kind of discussions did you have about that jump between those two worlds and how to deal with them without giving away “the reveal.”.

AXELRAD: When I read the script I thought, “This is going to be a challenge — in a good way.” And I’m always looking to challenge myself with bold material. And I knew that balancing tone was gonna be a challenge because it does change between Southern Gothic period piece, modern-day romantic comedy, horror, and action.

I’ve done a few of those films before where I’ve balanced horror and comedy. I did two of them: Krampus and James Gun’s Slither. That is kind of an editor’s dream and nightmare at the same time because you don’t want to go too far in one direction.

This film was a little unusual because there are very specific three acts the way it was written — where the first act takes place in the antebellum days on a plantation. Then we shift to modern-day where it goes a little more comedic and then the third act returns to the plantation and that’s where the horror happens and then it ends with some action scenes.

So it wasn’t so much intercut as much as an editor would want, but I totally respected and appreciated the three-act structure that the director-writers came up with. I fully embraced the script as it was. Just making it feel like one cohesive whole is what we as editors do — and also lose sleep over to make sure that everything is balanced just right.

HULLFISH: One of the things that I noticed was — it was very important, it seemed to me — to follow Janelle Monae’s character.

AXELRAD: Veronica or Eden.

HULLFISH

It was very important to follow Veronica’s point-of-view. Can you talk about point-of-view in your editing and either how you sense it and how you want to play with point-of-view or how you discuss that with the director?

AXELRAD: I’ve worked a lot with a director named James Gray. He’s kind of a neoclassicist with his filmmaking and he is very, very particular about point-of-view and making sure that your point-of-view is with your protagonist almost at all times.

Any time we veer away from the main character’s point-of-view — when I work with James — it’s done intentionally on purpose to call something out. Sometimes he’s had a side character looked directly into the camera, which was an interesting technique to kind of break point-of-view. It was almost Ingmar Bergman-like.

But with (directors) Gerard (Bush) and Christopher (Renz,) they purposely did break point-of-view a few times. We are with Janelle Monae’s character pretty much throughout the film, but in the first act we do go with Tongayi (Chirisa) who is a side character. We have an emotional scene with him.

We do spend more time with some of these secondary characters and leave our main character and I did bring this up to them — about breaking point-of-view. But their attitude was, This is modern filmmaking. It’s not chapter-and-verse that you have to stay in the point-of-view of the main character the whole time.

Again, I respected that. I’ve kind of been trained in the neoclassical way of James Gray but I welcomed something different and I think it really works.

It’s always been an audience favorite scene when we go with Tongayi and experience his emotional scene. But the point of view of the character — played by Janelle Monae — is the through-line between the three acts and without giving too much away, it’s also a change in perspective. We see the world through her eyes on the plantation and then when we get to modern-day we see a different side to her. And by the third act, we’re putting both characters together.

She’s Eden on the plantation and Veronica. In modern-day, and it culminates in the third act. Having that point of view and her perspective on the themes in the movie is hopefully what resonates with the viewer.

HULLFISH: I noticed it with things like there’s a scene where she’s in an Uber and she kind of realizes that things are not as they appear and instead of revealing it with typical coverage, it’s her character’s perspective. I also noticed point-of-view in another scene where she is talking to her daughter about an interview she gave on TV and when she’s talking to her daughter you’re clearly using the shot from an angle as if her daughter is looking at her.

AXELRAD: The filmmakers and the cinematographer — Pedro Luque — were very good about doing perspectives. Point-of-view in that sense, I can totally see what you’re saying.

I think that has a lot to do with camera angle choices and wanting to get into the child’s eye.

Also to make that scene that you reference in the Uber to make that scene a little scarier — not being able to see what was happening outside of her perspective. I take point-of-view and perspective — some people may interchange them.

The perspective of those scenes was definitely through her eyes. It was really to heighten the terror and the suspense. The filmmakers were very good about that. They really wanted to see things through her lens — through her world, and thematically that resonates in the film.

When we get to the end of the film and we experience her horse riding. Although we’re not necessarily seeing it through her eyes, we’re definitely seeing it through her point-of-view.

HULLFISH: I see the distinction you’re making here. Especially with the horse chase. You rarely see a shot as if it’s through her eyes, but we are experiencing it through her point-of-view instead of — say — her pursuer’s point-of-view.

So do you want to talk a little bit about what the difference is between — in your mind — perspective and point-of-view? Is point-of-view a more thematic idea and perspective is more literal camera angles? How are you seeing those two words?

AXELRAD: I do think of point-of-view in terms of more of a character arc. So I see point-of-view as a broader term. We’re WITH the character. So you can be in a character’s point-of-view being on a close-up of that character and sensing the world through their mind.

Now perspective for me is having — I guess you could call — point-of-view camera angles. Where we’re actually physically seeing the world through their eyes. So, to me, perspective is a little more specific to camera angle choices and mise en scene and how the director wants to portray the world, whether it be through a child’s eyes, a child’s perspective.

The scene you mentioned was definitely an up angle at Janelle Monae but still, the whole scene is within Janelle Monae’s point-of-view. But we’re seeing it through the child’s perspective.

HULLFISH: To use that same scene where they’re looking at the footage of her on a news program with her daughter and her husband. The point-of-view of that scene is shown in a wonderful shot of her watching herself and you can just see the play of emotion over her face. It’s almost like she’s reliving it or she’s re-experiencing it and relishing her decisive win in the argument.

AXELRAD: Exactly. And this is the point-of-view of the movie as a whole — in a larger sense — is Janelle Monae’s character and also the differences of her world on the plantation and her world in modern-day. She’s still the same person. So it’s really to get a better understanding of her having gone through the first act — which is long, it’s difficult for some to watch. We knew this film was going to be polarizing. There’s no doubt about that. I mean it’s bold and risk-taking. And some people are very uncomfortable through the first act because it really deals with the horrors of slavery and we don’t shy away from depicting some of the atrocities.

But then to see who this person is in the modern-day, hopefully, reinforces that point-of-view and then that prideful moment that you mentioned when she really sees herself put to shame this conservative pundit on national television.

The hope is really to have a better understanding of her character and hopefully that all comes together in the third act when she decides to defeat her oppressors.

HULLFISH: Another great scene showing her point-of-view — but not her perspective — is a scene where another slave on the plantation is saying, “What’s the plan?” There are great moments on Janelle’s face where she’s kind of getting challenged and instead of coming back and trying to challenge back she’s weary and frustrated and appears to have given up.

AXELRAD: What’s really interesting about that scene — I know the director’s intent is to show the generational gap between the older generation of African-American revolutionaries who have more of a Martin Luther King approach. “Let’s wait it out. Let’s be patient. Let’s continue to fight. You may lose the battle but we want to win the war” type of thing.

Whereas the younger generation tends to be more impatient and “let’s do it now.”

I found it interesting that this was the framework for what the directors had in mind. It’s the two generations clashing. Really in a larger context about what oppression feels like from different points of view in terms of “what should we do?” And it’s also the frustration that if we act now we may win the battle, but not win the war.

So it’s really something for all generations to reflect on. What do we do?

The oppression continues obviously in today’s world and this film is meant to be a mirror to what’s happening in society socially and politically today.

HULLFISH: You mentioned intent. Is that something that you discuss with the director upfront? Is it something that more happens during the director’s cut?

AXELRAD: I always try to have these conversations early if I can. I always want to be able to break down a script and really understand the intent — to almost take a continuity or scene cards and mark them up with symbols or notations of what the intent of every scene is because oftentimes during the shoot — and in the chaos of dailies or editing out of order — you want to always remember what the core intent is.

Unfortunately, a lot of times — and in this specific case of Antebellum — I got hired two weeks before shooting started and they’re on location and we’re editing here in Los Angeles and I couldn’t have those conversations as much as I wanted to.

That’s the unfortunate thing with post-production. As you know, we should be part of the preproduction process. I think it’s going to help the story overall. It’s going to help the whole editing process overall. If we’re there for the storyboarding if we’re there for the planning, the scene breakdowns, even rehearsals.

The more information we have about the director’s intent the better the first edits are going to be.

I will freely admit I totally missed the mark on many things. One of the scenes at the end where she’s riding a horse through a battlefield, I really didn’t understand what their intent was. They shot all sorts of footage. I cut it together — what I thought was a very beautiful, lyrical way. And that was clearly not what they wanted at all.

It would have saved us all a lot of time had I been able to have those conversations with them ahead of time, but unfortunately, there wasn’t time.

SIMON: But there were scenes during production where we were sending the director’s an output so that we could get their feedback on a scene — especially if it was time sensitive. That was really cool to be able to get their input. It was really great to get their feedback as soon as possible.

AXELRAD: Yeah. It’s always important to send scenes out. Whether the director….

HULLFISH: Watches them!

AXELRAD: Watches them or not.

At least I sleep better at night because one of the worst things for a director is to see the assembly. And actually one of the worst things for an EDITOR is to watch the assembly.

HULLFISH: (Laughs).

AXELRAD: There are things in there that are not going to wind up being in the final movie, but it is your obligation to include everything. This is the only version of the film where everything will be included and even though you want to cut a line of dialogue desperately or you know that the script is really overwritten in this section and we don’t have to have this certain scene in or it’d be better if the scene got moved somewhere else, you can’t do that because you want the director to see the script as shot.

That’s when you roll up your sleeves and start getting into it during the Director’s Cut to fix things. So screening an editor’s assembly is always painful. To Jared’s point, sending them scenes as you’re cutting them with the hope that they’re watching them kind of lessens the blow. When they see everything strung together for the first time.

SIMON: That was one of the biggest lessons for me that I learned from John on this. One of the scenes that I was assembling when it came in was the scene where they’re all with Janelle’s character and her friends go out to dinner.

I laid out the bin for that scene and I was very apprehensive of it because all the cameras were always roaming and you never knew who was gonna be on camera. And I was always very apprehensive of those kinds of scenes because as an up-and-coming editor — as an assistant editor — I just wonder, “How do I know who to cut to when?” I asked John if I could take a swing at it. I just wanted to see if I could do it.

John said, “Go for it. It’s yours.” I tried it and John was giving me notes the entire way and there were a couple of times where I called John and asked him to take a look at it. There were a few places where I felt like we didn’t need this line or we could do this. And John said, “No. We need to show them the whole scene.”

So what I learned was to create an alt of the sequence — like a sub-sequence — so I could do what I thought was a good starting point and keep it in our back pocket for later when the directors are in and reviewing. That way — for that scene and for many others — there were a couple of alts in the scene bins that as soon as the director sat down with John they were able to go through and we could present them immediately with other options.

HULLFISH: That was actually one of the questions I was going to ask John was: Do you create alts for those scenes where you know something has got to come out.

AXELRAD: Oh yeah. I always do it. I do it on the side. I just want to be prepared with that and if the director spins out watching something and he or she says, “This isn’t working!” I can say, “Wait. Hold on. What about this?”

One time I cut a scene for James Gray that had all kinds of coverage. They just shot a ton. And many different angles. Some were really cool and I felt an obligation — this was early in our collaboration together — to try to include as many of these different angles, tastefully, as I could. When he saw the first edit he said to me, “You know you don’t have to include everything that I shoot.”

But without proper communication how do you know that? Without knowing what the hero take is or what the hero angle is, we’re just kind of guessing what the intent is. For me, dailies is the most frustrating part of the process, because I’m always scratching my head and just trying to figure out, “What do they intend here?”

The script supervisor is very instrumental in helping me convey even offhanded comments on the shoot. I always ask the script supervisor to write down anything she hears. If the director says something like, “Well, we’re not going to use this, but we’re here, let’s just shoot it.” That kind of stuff is helpful to me.

So until such time as the director gets in the editing room, we want to have as many options prepared as possible to appease any frustration about an edit not working.

SIMON: That dinner table scene was another good example of not knowing what the intent was because when the suitor comes over to talk to Dawn you don’t see his face in the film. You never see his face and it was a very conscious choice that they had directed that way. And it’s one of many motifs that they use throughout the film.

We did have coverage of him and the first version of that scene had his face in there. And that was one of the first conversations we had with the directors when we got to that scene was, “We don’t want to see his face.” And so that was changed.

HULLFISH: It’s interesting that they would know ahead of time that they didn’t want to see the face — and this happens a lot, right? They shoot the coverage anyway because what if the studio says, “We’ve got to see the guy’s face.” Then you’re stuck. So for the directors to know their intent is to not show the face, yet to get coverage of it anyway but not communicate that intent… they maybe just want to see the editor’s take on it?

AXELRAD: I think it’s smart that they did get the coverage. I would always give a director advice that, “Hey you can be 100 percent sure on the set that you’re not going to need something and we’re going to shoot it a certain way…”

Oners are a good example of that. And I always plead with them, “Please get coverage. You just don’t know. You don’t want to get to the editing room and regret not having done something that was very doable on the set.”

Grabbing an insert of something. You think, “Well we don’t need that.” But if you’re there or have a B unit team, please do grab it if you can.

I couldn’t talk to the directors before I cut the scene. We noticed that his head was cut off in many shots but it was multiple cameras and one of the cameras was trained on his face for many of the takes and many of the setups.

Jared was right to edit it naturally the way that you would expect to see a scene, not knowing how they wanted it cut.

Another good example — when I was an assistant — and I worked for Anne Coates — along with Robb Sullivan — we were on the movie Out of Sight and that famous intercut scene between George Clooney and Jennifer Lopez. Really, that kind of got and the Academy’s attention. That was the scene — the intercut seduction scene.

They were two separate scenes. It was in the script as two separate scenes. And it was cut that way — as two separate scenes. It wasn’t until Steven Soderbergh got to the editing room and we realized he wanted to intercut them. Maybe he had that plan all along. Maybe he was waiting to get to the editing room to explore some new ideas. But it was so pivotal to the movie and the style — the freeze frames — everything like that was just so pivotal to the movie, but we had no clue that was something that Steven intended.

So I always tell directors, when they see an assembly — which, by the way, I think we cut very well considering what we can do with limited communication and cutting out of order. But it’s not what they envisioned.

It’s always disappointing to a director and I always remind a director that they usually have way more time in their director’s cut than they did in the shoot. Some movies shoot more than 10 weeks but a director will have 10 weeks to do their edit. And then it’s not really over after that. You get the producer notes, the studio notes, and the director continues to tweak, he just has more collaborators.

HULLFISH: Soderbergh’s an actual editor. He edits, correct?

AXELRAD: He does now. Anne Coates edited Out of Sight and Erin Brockovich. Steven Soderbergh started shooting his own stuff and then eventually editing his own movies, but I don’t think he started out that way. I don’t know. Sex, Lies and Videotape? Did he edit that?

HULLFISH: My thought was that I’ve talked to David Fincher’s editors and they said that Soderbergh contributes on edits on a lot of the Fincher stuff. Those two are more friendly collaborators, I think, than anything formal. But Soderbergh will go through and do an edit take on a lot of that stuff.

AXELRAD: He’s a brilliant guy. Very multitalented and he’s not the first director slash editor to have graced Hollywood screens and he’s very good at what he does. I didn’t know that with Fincher, but it makes complete sense.

HULLFISH: One of the things that I really like talking about — and I’d be interested in hearing both of your perspectives on this — is the idea of ego and the place of ego in the edit room. When you deliver a scene like the horse chase scene where the director tells you that it isn’t at all what they envisioned. That doesn’t mean your edit was bad. It means that you could have done a lovely edit and it was just not what the director envisioned.

Talk to me about how you deal with ego in the editing room. How important it is to have it, and how important it is to subvert it?

AXELRAD: I always joke that editors need to be more beta, dealing with alpha directors. Part of our job is obviously the craftsmanship of editing, but our job also is being part politician, being part psychologist… and I always throw in 1 percent magician.

You have to be able to read the room and you have to understand the egos and really what’s at stake for directors. They have so much pressure on them. If we put pressure on ourselves when we present an editor’s assembly, you can imagine what they feel when they’re having people watch it for the first time or when they’re presenting it to the producers or the studio for the first time.

I’ve worked with several directors that were both actor-turned-directors that couldn’t be in the room when a film was screened even when it came down to the preview screenings and stuff like that for audiences. They just could not physically be there. They were on screen. They both acted in their movies and that wasn’t the problem. It was just having the director hat on and having to deal with the criticism.

You have to support their ego. You need to support the process. You need to keep reminding them that this IS a process. That we will get there, even though maybe it’s not where they want it to be in that certain place. Remind them that maybe we need to do a day of insert shooting. That’s in the budget. You want to be able to offer solutions and think of these solutions ahead of time which is one reason I do alternate edits as Jared mentioned.

But also to really think outside the box and anticipate problems anticipate what they’re going to say or do and be there to offer support and solutions.

The most important thing is you just can’t take things personally. As much as it hurts — and I’ve had a certain director tell me something stinks that I’ve done — and deep down I know it doesn’t really stink. We may spend a week recutting it, and we’ll ultimately come back to something very similar to what was originally there, but having the director go through the process of discovery and understanding the dailies and understanding the limitations and to live in that moment and then come out on the other side of it. That’s where an editor really has to have patience.

I always say, “I serve the film itself” and not a certain person. I’m always going to express my opinion if I feel the film — as its own entity — needs something, instead of just being a “yes man” to the director. But at the same time I always support the director’s vision, and what they hope to accomplish.

Really, the process of working together in a director’s cut is understanding what their intent is, so I can get fully behind the director.

SIMON: A lot of times I would get called into the room to be like a tiebreaker to get an opinion. John and I had these adjoining offices. We had a shared door, so a lot of the times they’d be working and I would be right on the other side of the door or their door would be open.

The directors would say, “What do you think?” John always encouraged me to be honest, of course, and that’s who I am. I’m very transparent. A piece of advice that has stuck with me — that was given to me by another assistant editor when I first started out — “Don’t try to be the smartest person in the room. Just try to be the most helpful.” And that’s really stuck with me and I think that that has a lot to do with ego, because — especially as an assistant editor — a lot of times I’ll have an answer to one of many questions that will be proposed.

There’ll be five questions that get thrown out. “There was a shot that we had with an owl. And also we want to shorten this. And we want to extend that.” I have all the answers. It’s in the code book. I could search the word “owl” and it’ll come up and I can give them the exact two takes, but it’s not very helpful in the moment to share that.

I think alot of my ego to be say, “Yes! I know this!” So a lot of what I do as an assistant is listen and then I’ll come to John later and I’ll have all of the answers on a Postit.

Especially if I have an opinion about something, a lot of times I’ll wait to share it privately and then we can discuss it and see if it’s something that’s worth promoting.

AXELRAD: I think that’s very important, what Jared just mentioned about the demeanor of an assistant.

I have the best interests of the director in mind — and for my assistants — I always look out for them. But an assistant should have the best interest of the editor in mind that they’re supporting and not say something that creates work for an editor or creates problems for an editor.

I’ve been in a situation where I’ve had an assistant say something with the director in the room that caused problems and in that case the assistant was very green and didn’t know. I pulled that person aside afterwards and let them know the protocol.

Jared was very good about that, and I think having private conversations or having an idea for a scene — privately communicate that to the editor. I always give credit. I never try to take credit, but an assistant may not know where all the bodies are buried in terms of things that have been tried before and you don’t want to have someone say something that opens a can of worms. Maybe there’s somthing that I got a director to change their mind about something and I don’t want to go back there and have them say, “Yeah! That first crazy idea I had. Let’s try that again.”

It all comes down to communication.

HULLFISH: I always think that cutting a scene is important, but it’s a very small part of the process. That process is where the real work of it happens and to be able to see that part of the process is almost more important than cutting the scene at the beginning.

Talk about kind of the process that a scene takes from the editor’s first cut on and how you try to bring an assistant into that process or show them, “Here’s how it works.”.

AXELRAD: In the case of Antebellum, we were editing over at EPS, before the pandemic and we had adjoining rooms, so a lot of times I’d have the door open. Jared could freely listen to what was going on. Even with the door closed, he could hear everything that was going on.

It was kind of funny because I’d be talking with the directors. They would say something like, We could really use a temp VFX here and then we’d hear Jared say, “I’m on it.”.

SIMON: I tried to be as proactive as I could.

AXELRAD: To have an assistant editor be engaged like that creatively and to be listening in, it doesn’t always happen because rooms can be small and there’s not always that opportunity for an assistant to observe that part of the process.

They could be more involved during dailies and the first edits of scenes but sitting in with the director — sometimes directors want to just be alone with the editor.

When I worked with Tom Cross I would get him involved and I’d suggest to the director, “Let’s have Tom work on this while we’re doing this.” I always try to involve people creatively because I just think that it gets people inspired. It makes your team work harder. I never think fear is a way to motivate someone to work better and ultimately it helps the film itself. I just care about the final product.

I do whatever I can to have an assistant see the process of the edit during the Director’s Cut stage.

HULLFISH: Jared thoughts on that?

SIMON: I was really grateful that the directors were open to everyone being as involved to their interest level, and we were all 100 percent passionate about what we were doing. Not just me. Our second assistant editor Dave Levinson and our P.A. Marco Gonzalez. We were all involved and we were all engaged and as often as they could either Marco would be in my room or Dave’s room always asking questions and that mentorship mentality is one of the things that really attracted me to John and to Robb (Sullivan) and Matt (Rundell) as well when I first started working with them.

I’m very fortunate to be able to work with people who want to see me get involved.

Going back to ego and the evolution of the scene from the editor’s cut and how it evolves — I would never have my feelings hurt when I saw a scene I assembled and how it got changed because I always thought it was just so eye-opening to see.

I forget which scene it was, but John was reviewing it and I saw how different it was than how I had put it together. I love seeing a different perspective on it.

John is really meticulous about sound work as well and his expectations for himself are really high and that’s what motivated me to want to be able to get him to listen to something that I did and hopefully think maybe that’s something that he did.

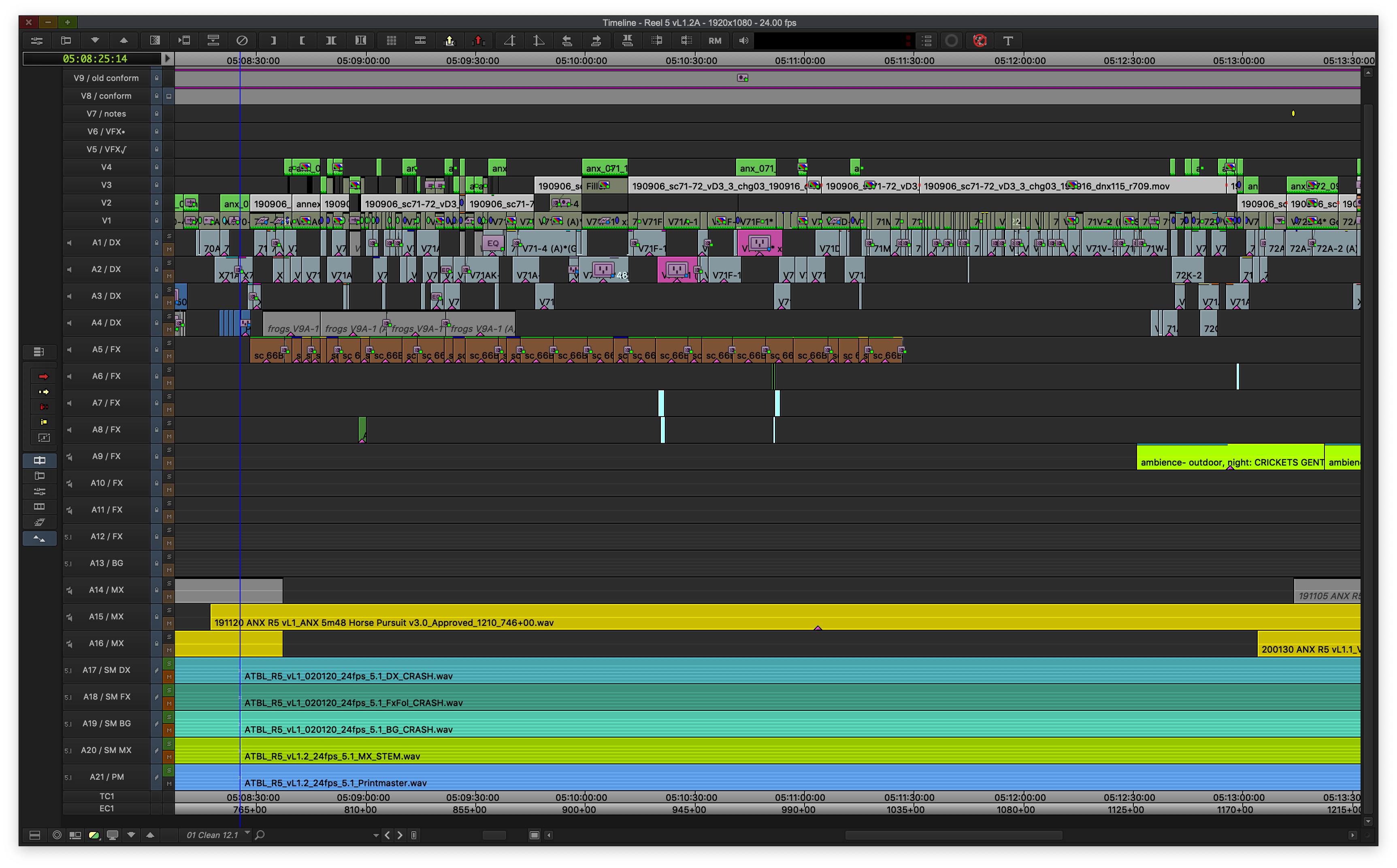

So a lot of times the evolution of a scene would be me doing sound work or temp VFX that would elevate it. One of the things — just because of our schedule and maybe our budget — was that we were doing previews and I don’t think we did a single pre-dub or temp mix for the previews.

We were cutting in 5.1 and we were really mindful about how we were putting together sounds. We had stuff from the sound department that they had treated and sent back to us specifically. That was really helpful and it sounded really cool.

They recorded frogs on location they sounded a little bit like goats. It was ominous and creepy. They blurred it together and they sent us a bunch of these 5.1 ambiances that were very unsettling and we incorporated those but things.

Using tools like Izotope RX and Mocha to be able to get some of these temp VFX to a level that doesn’t bump the directors when we’re trying to edit a scene and trying to get the point of the scene across or to show it to a preview audience where the effect or sound doesn’t take them out of the scene. I think that that was really important and that was something that I spent a lot of time on and I enjoyed spending a lot of time on.

AXELRAD: Some editors do object to doing sound work. Doing music work. And I totally respect the work that music editors do and sound editors do. They could definitely do things that I can’t even approach. I think some of that is a necessity to sell an edit where I just feel the need to — for example — really polish the dialogue here.

Jared introduced me to Izotope RX — how to create ambiances. How to EQ-match lines and stuff like that. We employed a lot of that and it is a lot of extra work but my goal is to sell an edit. Plus, for me, it’s kind of like fun time — the icing on the cake — playing with sound design.

But we had a terrific sound design team — David Esparza would feed us his design and we would incorporate it in 5.1 in the Avid.

We knew our schedule was tight. The budget of the film was under 10 million and we really wanted to maximize our final mix days, so the studio was very tickled that we were able to avoid temp dubs every time we needed to preview because we would handle the mix in the Avid and be able to project 5.1. And there was probably only one scene that we did a DI color correction on. Pretty much everything was straight out of the Avid.

HULLFISH: John, you mentioned early at the beginning of the interview that there were elements of this movie that were similar to a couple of other movies you’d edited in the past. Do you think that led you to landing this gig? Can you tell us about how you came to get this job or why the directors chose you?

AXELRAD: I interviewed with them. I had a hard time getting the interview. I finally did and I think I had a very good interview. They seemed to really respond to me. It was all through Skype. I remember they asked, “If we had to see one film of yours or parts of one film what would it be?” And I suggested that they see The Lost City of Z. I don’t know why I chose that. I mean, I’m very proud of the film.

They started watching it and it begins with a horse chase which is at the end of Antebellum. Now, it never occurred to me that they were going to respond to the horses. I had read the script for Antebellum, but as soon as they saw the horse chase they called me back and said, “We can see you can edit horses.”.

HULLFISH: (Laughs). That’s why I didn’t get this movie! Because I’d never edited horses! They just didn’t think I could edit horses.

AXELRAD: This business wants to pigeonhole you — and no slight at all against the directors — they obviously wanted to vet everybody and choose and I think they chose me for other reasons but I can’t tell you how many times I get turned down for an interview because they think, “Oh, he doesn’t have enough comedy” or “Oh, he only edits this” or “His pace is slow.”

Would you want to do the same thing over and over again? No. I try to mix it up as much as I can. I’ve been very fortunate to edit both romantic comedy, horror, some action, drama and I really try to not get pigeonholed, because this town really does want to do that to you.

But one of the reasons I got the job was horses.

HULLFISH: You’ve worked with some fantastic assistants. I’ve met Lee Haugen myself. I’ve interviewed Tom Cross several times. What is it that makes somebody stand out — either in an interview or it sounds like a recommendation from a close friend when you chose Jared.

What’s going to land an assistant a job with you?

SIMON: You trying to put me out of a gig?

HULLFISH: No, no! After this movie you can move up to editor and John is gonna be looking for another assistant. So how is that person going to get the job?

AXELRAD: In the case with Jared, he was very proactive. He reached out to me when I was editing on Ad Astra. I invited Jared over for lunch and we chatted and I thought he was charming and wonderful but at the time I didn’t really have anything.

Later, we did have an opportunity to expand the assistant team and I thought, “Well, let’s give Jared a shot.” Scott Morris and Lee were open to it, and then Jared just impressed. For me, it’s ideally having time spent with that person and just feeling something is clicking.

So a lot of times a person may start out as a second assistant or even an apprentice and work their way up. For me what’s really important is just having the acumen and the ability to anticipate issues. Jared will freely admit that he doesn’t have a long list of first assistant editing credits, but there is just something about his tenacity and his awareness and his ability to act and do things very efficiently that really spoke to me.

I thought, “He’s perfect. He’s exactly what I’m looking for. He’s anal-retentive like I am and a little OCD on stuff and wants to get everything right and that’s really what I appreciate.”

HULLFISH: Jared what are some of the things that you think in that description of “How does an assistant impress?” what do you think some of those things are that you do that help you show that you can move up?

SIMON: First, thank you for the kind words, John. I really appreciate it.

At the end of the day, I’m very grateful for the job. I love what I do. To quote Keanu Reeves, “I love movies! Gosh! I love movies!” I love watching them and I love making them and so that’s the primary driver behind everything.

To be able to work with people that make the day better is just fuel to the fire that makes me want to do my job so well.

I noticed what John was paying attention to and I made sure that those things were just as important to me as they were to John. I’m always paying attention to technology because that’s actually what I think got me interested in movies in general back when I was in high school. I was playing with computers and I found Final Cut 7.

So that’s kind of my angle. Now, as I continue to establish myself, I think one of the things that I’m really looking forward to continuing the conversation and growing as an editor — is the storytelling of it all.

Those are the conversations that I want to have and that’s what I look for, and that’s one of the reasons I want to continue working with John. I think all of these assistant tasks are kind of a setup for that — for being able to tell a good story.

It’s keeping track of these ADR lines and why they’re important for clarity. Is it because something’s muffled? It just adds to the list of things that I’m paying attention to when the dailies are coming in. So I have a more acute sense — when I’m watching dailies — of how to mark them.

There were things that John taught me about watching dailies when they were coming in. Marking a flub or reset but also marking a good moment. What makes for a good moment? Like the dinner table scene. John would drop a black marker for any really great reaction. Or we would mark green for improvisation. He would mark blue for any sort of camera bump or focus bump. I became more acutely aware of those sorts of things.

HULLFISH: I loved the diversion into markers in the point of markers.

If I can have a few more minutes of your time to just talk about tension. A lot of your movies, John, have incredible tension. This is one of them — where the tension builds and builds and you watch scenes and your heart is beating out of your chest.

What is it that you can do as an editor to enhance what they’ve done on set to build tension in a scene?

AXELRAD: That’s a good question. A lot of the projects I’ve worked on have that character intensity and I think it really comes down to character. I think you really need to invest in a character. Some scripts are in better shape than others, but as an editor, I’m just always interested in getting the emotion out of your main character.

We talked earlier about point-of-view, which is very important because you really want your audience to understand the point-of-view of your character and understand what the conflicts are — understand the character arc and you want to be able to root for your character.

So I don’t think you can fully experience tension unless you’re invested. In the story invested in the character. Some movies it’s easier to do. It has a lot to do with the performance. It has a lot to do with the writing. It has a lot to do with the way it’s shot. But, my responsibility as an editor is to convey emotion, and once you’ve got the audience hooked and once you feel the audience is not going to get bored or their mind is not going to wander and that they’re narratively engaged in the character and in the story, then you have room to let tension build because it’s only going to be most effective when you feel that your character’s life or ideals or well-being is at stake.

There’s horror tension — which is simply, you as the audience are terrified of something about to jump out, but when you’re talking about tension in drama, it’s embedded in the personality of the character.

HULLFISH: What was it like working with two directors?

AXELRAD: I really enjoyed working with the directors. It was my second time working with a pair of directors (2010’s The Switch with directors, Josh Gordon and Will Speck). I just really adore them and they’re very strong social advocates. They have a background in doing a lot of political work as well as music videos.

AXELRAD: I really enjoyed working with the directors. It was my second time working with a pair of directors (2010’s The Switch with directors, Josh Gordon and Will Speck). I just really adore them and they’re very strong social advocates. They have a background in doing a lot of political work as well as music videos.

I’ve worked a lot with a lot of first time feature film directors and I enjoy it. I enjoy guiding them through the process. Letting them know — from years of experience — what to expect from a studio screening or what to expect from producer notes.

I always look to forge a relationship. Gerard Bush and Christopher Renz definitely have expressed interest very strongly that I’m their editor for their next film. That’s what I find most prideful — when you make people happy.

As I mentioned, this was gonna be a polarizing film. There are gonna be people who would be offended by it and others would be moved and inspired to reflect on its message. Tackling issues of the enslaved from our country’s past is never an easy sell. It’s not what you would say is a feel-good atmosphere but it’s I think very important for social discussion. That’s really what we wanted to convey throughout this film is generating more discussion about the socio-political climate in this country and hopefully, we’ve done that. The movie starts with an uninterrupted, multi-minute, 1917-ish tracking shot. Can you talk about whether there was coverage in there or what did you have to do in that scene to be able to edit it or decide that it should be a oner? Well, this was the directors’ intent. It was actually early in the production when they shot this. I think they did about six or seven takes. I remember they said the light in this take was really good but the camerawork on THIS take was so much better, and the actors — their performance — was so much better in THIS take. So we wound up stitching three shots together and we found some secret places in which to do the stitching.

Jared did the preliminary stitching — was it in After Effects?

SIMON: It was a combination of things. It starts as a really beautiful shot and then it evolves into this really horrifying shot. We needed to stabilize it a little bit and then we added the wipes.

We had done a couple of things in Avid to try and stabilize it. At the time our apprentice editor, Nick Haridopolos, was able to bring it into After Effects and he fiddled with the warp stabilizer. I don’t know what he did, but it came out really smooth.

So I brought that back into Avid and we found the best places to do the wipes. I just used a key-framed Animatte. We comped three elements to get the best performance and the best light. I think they shot six or seven takes of one part of it and I think that there were nine takes of another part. It was a difficult time shot to pull it off but I think it came out really well.

AXELRAD: ILM worked on the sequence. They did wonderful work with it. We had to add in some bushes and things like that. Also, we worked with Temprimental. They added some butterflies at the beginning. So it was really kind of a multifaceted approach to make the shot work.

The thing that made it work is having the opening titles on it which I always — in my mind — said, “This really is perfect for opening titles.” They complemented the length of that opening shot and the titles turned out perfectly with the music.

HULLFISH: Do either one of you remember how long that shot was?

SIMON: About eight minutes?

AXELRAD: It was about eight minutes.

SIMON: Was the shot itself eight minutes or the opening sequence was eight minutes? I always viewed the whole opening sequence up until the title card because it’s all married to this one beautiful music cue.

Actually, we didn’t talk about music at all. That cue was sent by the composers early on. They had sent a bunch of cues to us that were sketches I think. Right, John? They’d written it just from reading the script.

AXELRAD: They knocked it out of the park. They scored that opening theme without having seen a frame of the film and it just really worked.

They couldn’t shoot that all in one take even though it looks like it’s one take, the Steadicam operator just physically couldn’t continue. There was at least one place where we had to stitch.

I think the shot was more like around six minutes.

HULLFISH: John, Jared, thank you so much for your time. I really appreciate talking to you about Antebellum.

AXELRAD: Steve, it was a pleasure. Really enjoyed our time.

AXELRAD: Steve, it was a pleasure. Really enjoyed our time.

SIMON: Thank you.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter and Instagram at @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed, and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now