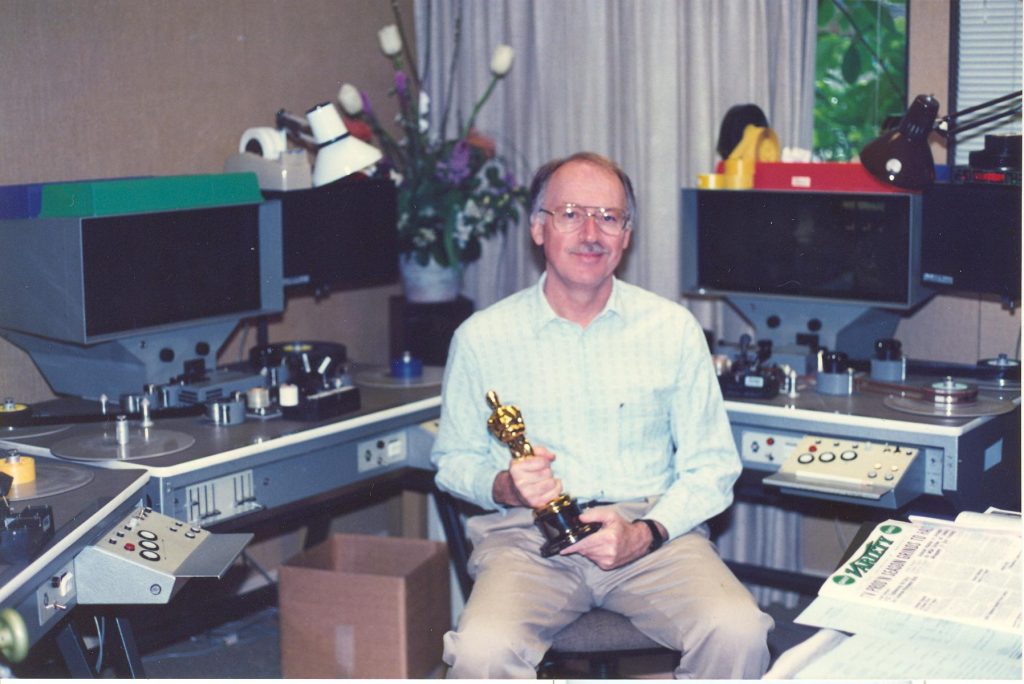

Today I’m talking with Arthur Schmidt, ACE. Arthur won an Emmy and an ACE Eddie for his editing of Michael Mann’s film, The Jericho Mile back in 1979 and has been winning awards and cutting iconic films ever since. He was nominated for an Oscar and an ACE Eddie for Coal Miner’s Daughter. Nominated for a BAFTA for editing Back to the Future. He was nominated for a BAFTA and an ACE Eddie and Won his first Oscar for Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Was nominated for an ACE Eddie for The Last of the Mohicans. Was nominated for a BAFTA and won an ACE Eddie and an Oscar for editing Forrest Gump. Was nominated for an ACE Eddie for Castaway. Won an ACE Eddie for Pirates of the Caribbean – Curse of the Black Pearl AND finally, won ACE Eddie’s Career Achievement award in 2009.

He also edited excellent films like Addams Family Values, Death Becomes Her, Back to the Future 2 and 3, Ruthless People, Fandango, and The Idolmaker.

It was an honor to have a chance to talk about his legendary career and about editing wisdom drawn from more than 4 decades in the editor’s chair.

This interview is available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: I’m really interested in Jericho Mile. Was that your first project and you won an ACE and an Emmy? (Jericho Mile is available in its entirety on YouTube.)

SCHMIDT: No. I don’t think it was my first project but it was certainly my first TV movie and I’ve done mostly little bits and pieces of TV before that and co-editing jobs, like on Marathon Man.

I was hired to only edit the running sequences in Jericho Mile and Michael Mann came in after I was there for about three days and I started editing the opening sequence and he had a friend with him and he asked me to show him what I had edited.

There’s so much material on this opening running sequence that I only had about 30 seconds. So I ran it and I had temped in “Sympathy for the Devil” so that helped a great deal. Michael said, “Thank you very much” and left the room. The next day when I came in I found out that he fired his original editor — whom I had not met yet — and turned the whole movie over to me and because it had an air date, he found somebody else to cut the running sequences.

So he hired somebody who’d cut a running sequence for a Budweiser commercial, and that didn’t work out so he dumped the whole movie on me.

HULLFISH: One of the things that I noticed about those running sequences was the use of some slow mo that’s in there. Is there a trick to getting into an out of slow mo when you’re cutting an action sequence?

SCHMIDT: No. I’m not aware of a tricks because that was the first time that I’ve ever done something like that. It was the material that I was given and I had to find a way to make it all work. So dissolves here and there certainly helped and then quite often I would try and find a matching movement from the end of one cut to the beginning of the next cut so that you just had this imitation of a wipe. I was just looking for anyway that would make it cut, so whatever worked for me.

HULLFISH: There were some dissolves in there but in looking at some of your later work in a sequence like that it seems like later on that you weren’t using as many dissolves.

Do you feel like there was something specific to that sequence or was there an evolution of the way you edit?

SCHMIDT: No. It was very, very specific to the sequence. We started going more and more into slow motion and I was trying to make it seem as if we were in the runner’s head. This is the euphoria that he was sensing and feeling. That was the main idea behind that, plus the use of music in that scene.

HULLFISH: I love that idea of getting inside the runner’s head. It’s a perspective thing, right? In those scenes – even though he was being watched by people around him – you’re trying to stay more on his perspective?

SCHMIDT: Well, I wanted to stay as much as possible with him and give some kind of indication of what was going on in his head at the same time, but I had to cut to the other various prison groups to see their reaction to this runner guy that they knew and liked or didn’t like, so it was a combination of when to cut to the White Supremacist when to cut the Black group and then later to the Chicano groups, so it was complicated.

HULLFISH: That’s the way the movie starts, and then you later learn the allegiances throughout the prison. So you’re just kind of setting that up in that first scene?

It made me laugh when you said that they hired somebody to cut the running sequences that cut a running sequence in a Budweiser commercial. I think Hollywood has a way of kind of pigeonholing people, like, “He’s a guy that can cut running sequences.”

SCHMIDT: That’s true. If he could cut a running sequence for a Budweiser commercial, he can certainly do this, but they hired me because they thought I’d cut the running sequences in Marathon Man.

There was obviously some truth to that because one of the producers of Jericho Mile was an assistant director on Marathon Man, so he knew there was an editor Marathon Man that had cut some of the running sequences.

HULLFISH: But looking at your career, you have hardly been pigeonholed.

SCHMIDT: I’ve been very lucky to have fallen into the movies that I’ve fallen into and to work with some great directors like Bob Zemeckis and Michael Mann and Michael Apted.

HULLFISH: When you’re working with those directors does it take some time for you to get used to a new director — for you to feel them out — to feel comfortable, to know how they like to work?

SCHMIDT: Oh absolutely. Especially when you’re doing your first movie with them. You want to establish a relationship. What I always tried to do was get a cut sequence in front of them as soon as possible so that we know we were on the same page and that we’re in sync together. It always seemed like no matter how many movies you’ve edited — and maybe won some prizes along the way — you’re still insecure because this is a new movie — you’ve never done one like this before. I always have that feeling: “Am I up to this?”

HULLFISH: I’ve interviewed 300 editors at this point — and you’re an Oscar winner — people like Carol Littleton, that edited E.T. she said, “When I go in in the morning, i’m not sure if I’m going to be able to cut a scene.” I talked to William Goldenberg. Same thing. Oscar winner. “I don’t know if I’m gonna be able to do this today.”

SCHMIDT: That’s a very real feeling. I always felt that, too. You’d think that you are going to be comfortable, and yet you have a new sequence — something that you’ve never cut before. You just have to find a way to do it right, and to find the drama or the comedy in it.

There’s always a challenge. With Coal Miner’s Daughter, I’d never cut a musical before or a music number before. They were complicated because it was mostly just Sissy singing, but still it’s music, it’s drama, it’s musical beats and rhythms.

HULLFISH: One of the things that I noticed with that movie was a beautiful sense of the scenes building to dramatic moments. Can you talk a little bit about — not necessarily the pacing of the individual edits — like the rhythm of the edits, but pacing a scene so that it builds to an emotional moment and doesn’t take too long to get there but doesn’t get there too fast?

SCHMIDT: Well, for me I think that’s mostly just gut reaction responding to the material because I don’t have any method that I use to cut musical numbers or dramatic scenes or comedy. I just have always tried to let the material speak to me and find the best way to edit the scene with the material that I’m given.

HULLFISH: Do you have a specific approach — especially now that it’s more digital — do you do selects reels? Do you watch your dailies in a specific order? How do you start to build a scene from nothing?

SCHMIDT: I always went through and made selects. When I was doing it on film I’d pull that roll out because it was the best roll of close-ups that I had and work from there. Also, I’d make notes about readings and what was good about a particular take and then narrowed down to the best master, the best over-the-shoulder, the best medium shots so that I could push some of it off to the side and it doesn’t feel so intimidating when you’re looking at how much film there is on a particular sequence.

HULLFISH: And then with your selects narrowed to the best setups, is it then more a question of when you want to be in each shot? Do you build linearly after picking the best set-up to start the scene with?

SCHMIDT: That’s exactly what I would do. The obvious rule of thumb is you start the sequence in the master and then move gradually towards the other angles, eventually ending up in close-ups. But that’s kind of a basic rule of thumb, but you can throw all that out and do it the way you feel or the way the material starts to speak to you and break all the rules.

HULLFISH: Do you remember when the first project was that you switched from film editing to non-linear?

SCHMIDT: Forrest Gump was the last movie I did on film and The Birdcage was the first digital film.

HULLFISH: Wow. Forrest Gump was cut on film! KEM, Moviola? Steenbeck?

SCHMIDT: KEM. Then, like all of us film editors, I had to go and learn non-linear editing and I specifically said, “I don’t want to learn all of that stuff that the assistant does or has to do because I’ll never use it.”

I said, “I just want to learn the tip of the iceberg so to speak so that I can just concentrate on editing per se.” It made some sense to me but at the same time I always felt insecure because up until that time I knew how a cutting room worked. I knew how it was organized. I mean where the outtakes were — what the outtakes were.

So there was a certain insecurity there and I relied on my assistants for a lot of help in getting me out of a technical jam if I got into one — which I did.

HULLFISH: I’ve found that most Hollywood feature film editors — even documentary editors — rely heavily on their assistants for that kind of stuff.

Then on The Birdcage were you on Avid?

SCHMIDT: Yes.

HULLFISH: Do you remember the other editors — your other colleagues — people that you spoke to, friends in the business, how they felt about the transition to non-linear and what the discussions were?

SCHMIDT: I don’t remember. I just remember that it was something that everybody was doing and that I had to do. That’s the way film editing was going. I don’t know that those people would let me edit on film — if in fact it had been shot on film and then transferred to digital — but almost everything was being shot on digital.

HULLFISH: Forrest Gump is right on the edge of that transition. It could have been cut on film. It could have been cut non-linear probably that year.

That seems like a daunting movie to have cut on film. Was there just a huge amount of footage for a film of that type?

SCHMIDT: There was a lot of footage, but I wouldn’t say that there was a huge amount of footage as I recall.

Tom Hanks, from the very beginning, he was doing a wonderful job as Forrest, so there wasn’t an enormous amount of film to find the performance.

No I can’t say that there was an enormous amount of film except on some of the running sequences where some of it was shot by second unit.

HULLFISH: Maybe I’m more thinking on the scope of his life needing to have so much footage. I’m imagining it more than anything else.

Was that a challenging movie? Specifically the challenge of finding the tone and balancing the tone of something like the comedy of — I think of the ping pong sequence at the White House — compared to some of the more dramatic scenes.

SCHMIDT: I just cut each scene for what the scene seemed to be. The ping pong scene was a funny scene, so I just wanted to get the most humor out of it. I knew — pretty obviously — what the scene was all about and it had to be fun for everybody because it’s pretty silly.

I was blessed to have the wonderful performance from Tom Hanks.

HULLFISH: And then you cut another film with him too: Castaway.

Was that a challenging film to cut just because so much of it was with only one person?

SCHMIDT: Oh absolutely. Yeah. One person on an island and so many montages about them surviving on the island et cetera. So yeah, it was a big challenge.

I said to Bob — when he gave me the script — I said, You’re making a sort of Boy Scout manual of how to survive a desert island? That’s more or less what it was, but what a bold thing for Bob to try and make. He did a beautiful job.

HULLFISH: Yeah absolutely.

SCHMIDT: And gave me wonderful material that I was determined not to screw up or too sentimentalize or try and get any phony emotion out of what was going on with Tom and the character at that time.

HULLFISH: To get back to that question about directors — since you mentioned Zemeckis — do you find that you need to change your methodology or the way that you work for each director? Do you find that with Zemeckis can’t show him something that’s raw — or he can handle something that’s rough and another director can’t?

SCHMIDT: No. I never had that. I would just edit each scene as they’d come in and if necessary show it to him if he had the time while he was shooting. Or, if I was feeling insecure about how I’d edited a scene, then I’d have him come in.

It was easy for me to say to him, “I don’t get this. I don’t quite understand why you shot this scene the way you did. And I don’t know quite what to do with it.” Then he’d give me an indication or tell me if I was on the right track et cetera.

HULLFISH: I think that’s a powerful lesson in humility for some beginning editors that wouldn’t feel like they could do that. For example, on a movie that I cut recently I felt pretty comfortable with most of the scenes, but I got to one scene where I could not parse what the idea was. And you have to ask. I don’t think there’s a problem in asking, “Where are we going with this scene?”

SCHMIDT: Oh, absolutely. That happened to me a lot with the Jericho Mile and Michael Mann — once he turned the whole movie over to me and got rid of the previous editor — I can’t tell you how many times I’d cut a scene and then look at the material for the next scene and I’d go into Michael and say, “Michael, I don’t understand why you shot this scene the way you did and I don’t know what to do with it. Would you come into the room and help me out?” And he would say, “No, no, no. You just go on and do whatever you feel like doing.” Just having him say that, gave me total freedom to screw it up or do whatever I wanted. But there were so many sequences where I didn’t know what to do with the scene.

HULLFISH: And he was probably happy to see what your vision of the scene was. He knew what his vision of the scene was, so he could always get it to that point probably, but why not see what your vision was?

SCHMIDT: Yeah. I hope he had a vision of what the scene was but he couldn’t tell me what it was until he saw what I did to try and find his vision in the material.

We had a great relationship that was a lot of fun — and hard work and long hours seven days a week — but we were very comfortable together.

HULLFISH: That’s great. So we talked about assembling the dailies into cut scenes, but then there’s a much longer process of discovering the film from those assembled scenes and the process that happens after that — when things are in context. Can you talk about some of the things that you’ve discovered in various films from Jericho Mile to Pirates of the Caribbean — how the film evolves and what the process is once you’re done with the editor’s cut.

SCHMIDT: Well once you’re done with the editor’s cut, then of course you’re working with the director so it’s the two of you just honing in on the movie and getting it down to size and getting the best performances.

HULLFISH: Since you’re originally a on-film editor, has the process changed much in the revision and sculpting part of the process? Now it’s so easy to rearrange and revise.

SCHMIDT: It was only different in that one was on film and you had to unstick the cuts. My favorite button in digital editing is the undo button. So making changes digitally was just much easier and much faster even though quite often I had to rely on my assistants for a little bit of help there, especially if the director was in the room and wanted things to go a little faster.

HULLFISH: Another movie that I’m interested in the challenge of cutting was Who Framed Roger Rabbit? because that’s pre-NLE.

SCHMIDT: That was all on film. And all without any animation in it. There was no animation in it when I cut it. There was just space for the animated character — Roger, or whoever the animated character was in the scene.

HULLFISH: Wow! And then those things were added later. Did you have to imagine things? Like I think of something that you received as a plate of somebody’s eyes bugging out of their head or something like that.

SCHMIDT: I did have to imagine things, but one of the blessings was that the first take of every setup for a scene had somebody walking a dummy of Roger Rabbit through the scene, so I always knew where Roger was meant to be, or if it was a medium shot there was an empty space where the animated character was going to be and of course there was a live actor — Bob Hoskins there, so it was pretty obvious that that space was going to be filled by the animated character, and I always had the dialogue.

There was always somebody reading Roger’s dialogue off-screen, so it was a challenge to do, but it was a very invigorating challenge because everybody who preceded me had done their homework and done a beautiful job to set it up for editing.

I always knew where Roger was or where the other animated characters were meant to be. So everybody on that film did such a great job. I can’t say that it was ever easy but it was as easy as it possibly could be because everybody did such great work.

HULLFISH: Obviously animation takes a long time to do. Did you come back when the animation was done to edit that in or were you off onto another project by then?

SCHMIDT: No I was on Roger Rabbit from start to finish because there was always work to do. I don’t think I was ever sitting back.

There’s a scene in there where they go into Toon Town, and that was shot a month or two after the main film was shot, so there were always things to do.

HULLFISH: Pirates of the Caribbean seems to be the first film you edited as part of a large team — you’d co-edited a few times before that with one other editor. Can you talk about editing with a team instead of editing by yourself?

SCHMIDT: Yes. I was not the first editor on Pirates of the Caribbean. The other two guys were there ahead of me. Disney hired me to edit the movie Under The Tuscan Sun, which was a very popular book and was going to be made into a movie. It was with a first time director who was a woman and they wanted me to be there to edit the film and to sort of guide her along.

One of the perks of that movie was that I would get to go to Italy while it was shot on location in Tuscany. I’d be in Rome and it also meant for my wife going back to where she grew up. Rome is her home.

And at the last minute Disney called me and said “Artie, we can’t afford you. You can’t go to Tuscany.” And I said, “Oh no no no! I’ll come down on my price.” They said, “We want to put you to work on Pirates of the Caribbean, because the studio’s really nervous. The movie is going way over schedule and way over budget and they’re terrified of Johnny Depp’s performance, so I said to them, I don’t want to work on a movie that’s based on a dumb stupi Disney ride that I really sort of hated.

There was a time during one summer in my youth when I was a youth counselor at a summer camp and we used to take the kids to Disneyland and I got so fed up with taking the kids on that ride that I said, “Oh no! I can’t do this.”

I thought it was because Disney was unhappy maybe with the was the film was being edited by two editors who maybe were relatively unknown to Disney at that time. But I went in on my first day and they put me in a projection room so that I could see the eighty-five minutes that the two other editors had cut and they’d done a beautiful job. It was a first cut and it was terrific.

I came out of the projection room and they were both waiting for me to see what I thought. I told them I thought it was great, in fact I said to them, “I don’t know what I’m doing here.”

We obviously worked together and divided the film up into thirds and I got the opening third and my big job was Johnny Depp’s performance because he was all over the place and there was an awful lot of footage. I’d never seen so much footage of one actor trying to find his character.

HULLFISH: And then trying to shape that performance obviously.

SCHMIDT: Yeah that was an enormous amount of work.

HULLFISH: What were your guiding principles with that? Because it’s a classic performance. I mean, everybody knows that performance, but it is right on the edge. As an actor, you’ve really got to go out there quite a bit and trust your editor, actually. I think you’ve got to trust the editor to find the best moments and to build a performance that’s cohesive.

SCHMIDT: Well that was my job in the first third of the movie. Disney was panicked that their big summer movie was going to feature possibly a gay sailor and they really were concerned about that. So it was a huge challenge because there was so much footage on Johnny’s performance — and he was all over the place — but got it down to an acceptable Johnny Depp performance.

HULLFISH: The trick with that of course is that since you’re working with two other editors and a performance that needs to be crafted like that, you’ve all got to be taking Johnny in the same direction, right? Because if you’re choosing more understated performances or more over-the-top performances and the other guys are choosing the reverse, that’s not going to work for the cohesiveness of the film. Did you have conversations about it?

SCHMIDT: I don’t remember that we did. We just knew that we had to get an acceptable performance out of Johnny, and the two other editors had already been conscious of that — not that Disney was aware of what a good job they were doing. The other two editors were just kind of an unknown quanitity to the people at Disney where I was a known quantity because of Roger Rabbit and other movies that I’d done there.

They did a wonderful job.

HULLFISH: Do you think that working on an NLE has changed either your approach or the pacing or anything about the way you edit?

SCHMIDT: If there was a change, I wasn’t aware of it. I was determined not to let that happen even though I wanted to be open to anything new that non-linear editing opened me up to, but I didn’t want to close any doors about the new way of doing what I did, so I tried to just do what I always did — tell the story.

HULLFISH: Could you talk a little bit about the difference or the benefits about watching dailies back the way you used to watch dailies compared to the way that it’s probably changed since you’ve been on an NLEs? Or have some of your productions actually done dailies screenings with heads of departments and that kind of thing.

SCHMIDT: I don’t remember that we did that with nonlinear editing. I think in most cases the studio heads would get their version — their non-linear dailies and we would get ours and go from there.

On The Birdcage with Mike Nichols we did go to dailies.

HULLFISH: But that was transitional you said. That was your first film. On the films before that, there was a typical dailies screening with the director, with cinematographer?

SCHMIDT: Yeah always.

HULLFISH: Can you talk about the benefits of doing it that way?

SCHMIDT: Well I was sitting with the director and seeing it through his eyes and being there you kind of feed off each other’s vibrations and then talk about what you’ve seen afterwards and make your select takes.

HULLFISH: At some point those shared screenings stopped. Didn’t you feel like you were going to lose something by not having that typical dailies screening?

SCHMIDT: Yes. I’m just trying to think of what happened on subsequent movies where there were dailies and can’t remember sitting with Bob Zemeckis and looking at digital dailies. I think we all kind of went our individual way where the director would look at his dailies when he got home because they could do that digitally.

Or they’re looking at them on their iPads on the way home, if they have a driver, which most directors did. But It all changed. You’d get his notes the next day.

HULLFISH: Can you give some examples of working styles? Did many of your directors want to sit with you? Was that too frustrating and boring? Or was it simply sitting in, watching a cut, giving some notes, and saying, “I’ll be back in a day” or something?

SCHMIDT: With Bob Zemeckis, he always said that his favorite part of making a movie is editing and Bob was in the room most of the time. He might — towards the end of the day — give me some changes and he’d leave and I’d work a couple of more hours making his changes, but most of the time in post-production — after he’d had his two weeks off to recover and give me a chance to get the movie into an editor’s cut — he was there. It was his favorite part of making movies.

He was never somebody who was sitting there saying, “Do this. Do that.” It was always a combination of the tools and just listening to what a very intelligent smart movie-loving guy has to say.

HULLFISH: Do you think there’s a difference in watching a film in a projection room where you don’t have control versus when you’re on an Avid and you can stop and make changes immediately? Does that change things for you?

SCHMIDT: Oh yeah. Sure. In the old days — like you said — if you are running a projection you can’t stop and make changes but you can stop the projector and run the film backwards and then forward again to specifically examine a cut or whatever the director might be concerned with. “Rock and roll” with 35 millimeter reels in the projection room took place.

HULLFISH: I’m still really interested in the idea of the process — especially with somebody that loves editing as much as you say Mr. Zemeckis did — what was the process of getting a film into shape from the editor’s cut? What were the things that you were seeing that needed to change as you were going through?

SCHMIDT: You have the director sitting next to you and he talks about what he likes or doesn’t like and you’re always reviewing the outtakes and different performances from the actors. So, we’re wide open to Ideas and changes and things that I might have thought of as I was editing — different ways to do a scene or a portion of the scene — but obviously I have to make a decision and do it the way I ended up doing it and showing it to Bob and then talking about other possibilities with him and waiting to see his reaction to what I’ve done.

HULLFISH: I’ve had the discussion with many editors about whether you diverge at all from the script when you’re cutting the editor’s cut. Are you in one camp or another? Because some people say, “If I think I want to drop out two or three lines and the scene is going to be better, then I do it.” And other editors say, “No! The editor’s cut is always done to the script.”

SCHMIDT: I’m in the last category because my experience of doing it the other way is that the director always misses what you’ve taken out. It was always better for me to let the directors see the whole scene without taking anything out. Otherwise it’s disconcerting for the director because — unless you tell them in advance — they’re going to say, “Well, why did you do that?”

So to me it was always best to put it in the first cut the way the director expected to see it and the way it was scripted.

HULLFISH: And then what’s your approach as you move on from that? You’ve obviously got an idea: “Oh, I think this scene would be better without the first three or four lines.” Do you wait to see whether the director has the same feeling or do you instantly start asking, “Hey, what do you think about dropping those lines?” Or is it on a per director basis depending on how you know they like to work or your relationship with them?

SCHMIDT: Well I think it’s a little bit of everything that you just said. It is about relationships and how free and open you feel that you can be with them. And just to see if maybe they’re going to say the same thing that you’re feeling and then go from there.

I’ve worked with such wonderful directors that they’re also good editors and they know when a scene is playing too long or when there is dialogue that we can lose. So it’s a back-and-forth process with the two of you and then with the producers and then with the studios and then preview audiences telling you how you should make your movie.

HULLFISH: Do you sit in on those screenings? Do you like to do that or you find that there’s a value not necessarily in the notes that you get from a screening but in the sense of the room — reading the room as you’re doing the screening?

SCHMIDT: I like to be in those screenings with the producers and studio execs for the most part. Sometimes for the studio executives, the first time they see it is at a preview or screening just before a preview.

I want to be in those screenings — or certainly in the meeting that takes place afterwards — so that I hear what they have to say and we can talk about things.

HULLFISH: Does it give you a fresh eye for the material? Does it give you some objectivity to see how a screening audience is feeling about it? I feel like I see the film differently than one I see it in my edit room.

SCHMIDT: Oh absolutely. That was always the case to see it with an audience and their reactions. Directors that I’ve worked with always liked to bring a trusted friend into the projection room to look at their cut to just get some feedback from somebody who was knowledgeable about filmmaking and whose reaction the director felt that they could trust.

HULLFISH: Do you bring in assistants as you’re cutting a scene — before even maybe you play it for the director — just to get another pair of eyes?

SCHMIDT: I would do that occasionally but I regret not having done more of that because it would have been good for me and good for them to see what an editor goes through in putting together a first cut.

In my case, my assistants are always so busy — so overloaded with work — that I sometimes felt it just cut into their time, but I wish that I had done more of that.

HULLFISH: I read an interview with you where you mentioned the difficulties of cutting action scenes, and you said, “I think dialogue scenes are harder than action scenes.” Can you talk about how an action scene and a dialogue scene are different in approach or why you think one is harder than another?

SCHMIDT: I think that dialogue scenes are just so much more subtle obviously than action sequences. You can get away with murder on action sequences. You just cut and cut and dazzle the eyes of the studio heads, whereas dialogue sequences are much more full of nuance and subtleties than action sequences.

HULLFISH: You have won a huge number of awards. You’ve probably won more awards for movies than most people have actually cut movies. That’s certainly true for myself. Can you tell me what you look for when you’re putting in your Oscar vote or your ACE Eddie vote? What makes you think a movie is well edited?

SCHMIDT: That’s a tough question. It’s just your reaction, my reaction to the way it all works in a smooth and dramatic or comedic way and that there’s nothing in what I’ve seen that bothers me or jerks me around or manipulates me. That’s one of the things that we editors get accused of is manipulation, and I always hated that term and never felt that that was what I was trying to do. I was always trying to be honest with the material.

I just sit back and watch the movies and react to what I’ve seen in terms of good editing or bad editing.

HULLFISH: I’ve got to follow up on that because I’m very interested in that word “manipulation” when it comes to editing and I can certainly understand that you don’t want to FEEL like you’re being manipulated, but don’t you think that so much of editing is manipulating the audience and trying to be invisible about that? But that you ARE manipulating?

You’re deciding, “I’m going to this reaction shot because I want to manipulate the audience’s feelings about the relationship or something.”

Or do you just think that’s a bad word: “manipulation.”

SCHMIDT: I think that’s a bad word. I know what you’re saying but at the same time you were saying you’re doing the right thing for the scene at that moment dramatically or comedically. So maybe all editing is manipulating then… to me, it was always about telling the story, and I hated that word “manipulate” and if I ever felt myself going in that direction to maybe pull out some extra emotion or something by overcutting to get more emotion out of it, I always backed off.

One of the things that I loved about Coal Miner’s Daughter was the way it was directed and Sissy and Tommy’s performances were so real and so genuine and Michael Apted’s direction was so wonderful that I just was inspired by that, and I just wanted it to be honest.

Like the first time Sissy gets up and sings in a club that I just had to let her do it and not overcut to the audience reactions too many times or to Tommy Lee’s reaction and just let the scene go — let the scene play.

HULLFISH: That’s one of my favorite scenes in that movie is that opening — convincing her to go up on stage….

SCHMIDT: That’s a great sequence. I just sat back and looked at the dailies on that scene and said, Don’t you mess this scene up! Because you don’t have to do anything to make it better. Just be true and as honest to Sissy’s performance.

HULLFISH: Absolutely. Mr. Schmidt thank you so much for spending so much time with me and for so many candid and interesting answers. I really appreciate your time.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed, and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.