Roger Barton has edited many of the biggest and most iconic films in Hollywood history. As an associate editor, he worked on Titanic and Armageddon. His films as editor include, Gone in 60 Seconds, Pearl Harbor, Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith, Eragon, Speed Racer, all four Transformer movies, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales, Terminator Genisys, and Godzilla: King of the Monsters, among many others. He’s currently editing Michael Bay’s 6 Underground.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

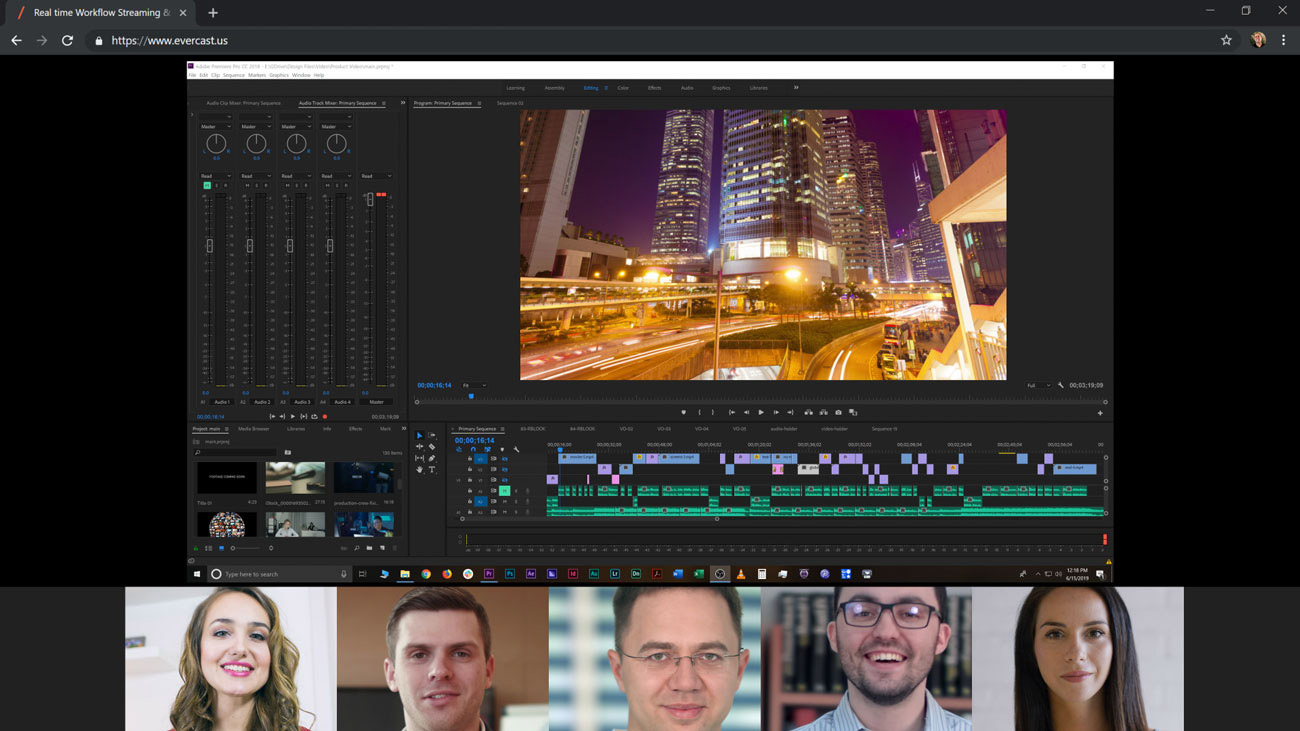

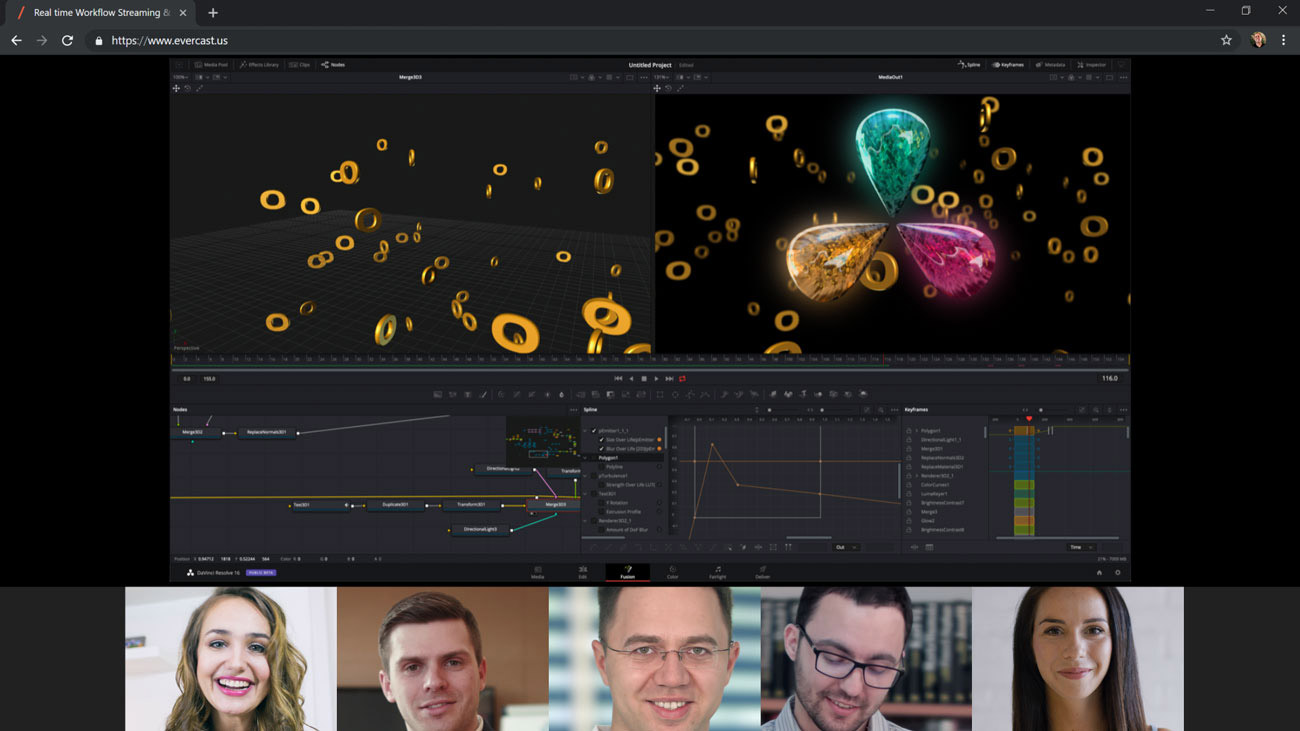

HULLFISH: You and I have been trying to connect since you edited Godzilla: King of the Monsters. I’m really glad we finally were able to make it happen. I was talking to the editor of Chernobyl recently and he was telling me about this service for remote editing called Evercast, and then I found out that you not only used it on Godzilla but actually started working with the two founders to develop it and implement it at some of the studios.

BARTON: I became involved in Evercast while I edited the last Godzilla film. At that time, I was about six months separated from my wife and I had a 13-year-old son who was trying to navigate this new scary world. I was approached by Legendary Pictures to do Godzilla and though I really wanted to cut the film, I couldn’t leave my son behind and to go to Atlanta for four months.

HULLFISH: God bless you for that.

BARTON: So as chance would have it a buddy of mine who lived across the street from the house I was renting looked me up on IMDB and said, “Oh my God! I didn’t know you edited these kinds of movies…” (whatever that means…), “…you should reach out to my friends who are developing this new remote collaboration tool called Evercast.” As he described it to me, I couldn’t believe it, because it sounded exactly what I was looking for and I think the industry has been hoping for, for many years.

They organized a demo for me the next day that began when I received an email invite which contains a URL that you open with Google Chrome. As long as you have Chrome and a webcam, you can join an Evercast room. (iPad, PC Windows, and Linux are all being released very soon). I connected with the two creators of Evercast, Brad Thomas and Alex Cyrell from my home while I was on my laptop using a standard wireless DSL connection. They were connecting to me, each from their own homes in Arizona. I was completely blown away by the lack of latency, the quality of the image, and the forethought put into the platform, specifically with regard to creative collaboration. I’ve used several other platforms and/or combinations of platforms which is why Evercast really impressed me — they basically took the best ideas of each and built them into a platform that is live, and doesn’t require you to spend lots of money on proprietary equipment.

So, back to Godzilla. I desperately wanted to stay in Los Angeles and try using Evercast to collaborate with the Director, Michael Dougherty who was already in Atlanta. I approached Valerie Flueger Veras, the head of post at Legendary, who supported me (thank you Valerie!) and introduced me to their head of content security, Dan Meacham. After vetting the platform up and down, Dan gave us provisional approval to use it and that was a huge hurdle because obviously, no studio is going to allow their very expensive IP to run over the internet unless it’s absolutely bulletproof.

The biggest hurdle still remained – a test with the Director. By this time I had a couple of weeks of footage to play – and the expectation was that I would be traveling soon to Atlanta for an unknown period of time. It was a Sunday afternoon when we decided to do a test, so I sent Michael an invite and shortly afterward he popped into the Evercast room with no tech support required. I was in my cutting room in Burbank, streaming out of my Avid to him in his apartment where he was on his laptop connected wirelessly. What started as a test effortlessly turned into a working session where we just stayed on the platform and worked for three hours. I was able to show him cuts; make trims, change takes all with him live as if I was doing the changes with him sitting right behind me.

Here’s the best part, I recorded the entire session. This enabled me to relax, knowing that I could replay it all the next day to make sure all the notes were done and done accurately. As I said, many of small notes or experiments, I did live with Michael, but for more complex ideas that require time and thought — I would do later by playing the recorded session back while I followed along with my Avid. Evercast records each stream individually, so I could switch between the main screen to view either his recorded webcam or the content was was being streamed at the time. This meant that nothing was lost in translation.

Anyway, at the end of the three-hour session, I said to Michael, “Do you still want me to come out to location?” And he said, “God no! Why would you want to come to Atlanta for three months, let’s continue using this.” That was a life-changing moment because it started me on this new path as I try to promote something I believe can improve the quality of our lives. I’ve always shied away from the spotlight, so in many ways, this is uncomfortable for me but if I can make a small difference or help other families stay together — it will have all been worth it.

HULLFISH: That sounds fantastic. Did the technology of it kind of melt away? Because human interaction — you and I are on Skype right now: I can see your face, I can see whether you’re getting antsy or whether you’re engaged. Did you feel like you were really engaged with him like you would be if you were in the room?

HULLFISH: That sounds fantastic. Did the technology of it kind of melt away? Because human interaction — you and I are on Skype right now: I can see your face, I can see whether you’re getting antsy or whether you’re engaged. Did you feel like you were really engaged with him like you would be if you were in the room?

BARTON: Very much so and not always in a good way, (both laugh). I think a lot of editors will understand this: I’m used to running first cuts for directors and usually they’re behind me where I can’t see their reactions…but on Evercast I’d see his facial expressions as he’s watching the cut live — just like I’m watching you right now. And so whether it’s a laugh, a smile, a grimace or whatever, I could make note of it…good and bad. Thankfully I could mute his camera from my side if I had clearly F’d up a scene (laughs).

Before this experience, what I’m used to — is being sent to location for months at a time, trying to pull the director into the cutting room after a 14-hour shoot, where literally hundreds of people are nipping at them all day for answers. I’m usually the last person they want to be with at the end of the day, which is never a good time to be showing your first cut.

On Godzilla, by staying in Los Angeles and using Evercast, I literally got more collaboration time with the director than I ever have — even when the production sent me and my crew to location. In most instances it was Michael who initiated the Evercast sessions, whether it was a five-minute quick question, 30 minutes between lighting setups or an hour session at lunch, all he had to do was open up his laptop, hit his bookmark in Google Chrome and we would be in the room together. We took advantage of all those moments on set where he had downtime and in most cases, he was totally relaxed because I wasn’t trying to force him to be there.

Michael shot 3 million feet of film so I averaged between 8 and 12 hours of dailies a day which meant I had to adapt my workflow in several ways, but using Evercast enabled me to collaborate with him and get his eyes on sequences early. In fact, by the time he returned from shooting, he had a pass on many of the scenes and certainly all the big set pieces because we had early VFX turnover obligations. Getting this early feedback translated to far less anxiety when Michael returned from shooting – because he already knew what movie he had shot, and any missing footage we needed I could easily ask for by streaming the cut to the set — rather than exporting QuickTimes, uploading them on other platforms and waiting for a response that often never came.

Michael shot 3 million feet of film so I averaged between 8 and 12 hours of dailies a day which meant I had to adapt my workflow in several ways, but using Evercast enabled me to collaborate with him and get his eyes on sequences early. In fact, by the time he returned from shooting, he had a pass on many of the scenes and certainly all the big set pieces because we had early VFX turnover obligations. Getting this early feedback translated to far less anxiety when Michael returned from shooting – because he already knew what movie he had shot, and any missing footage we needed I could easily ask for by streaming the cut to the set — rather than exporting QuickTimes, uploading them on other platforms and waiting for a response that often never came.

HULLFISH: That’s interesting.

BARTON: It takes away that impersonal element of sending a cut to the director and then waiting for feedback days later. And in the case of visual effects reviews, it allows eight to ten groups from anywhere in the world to come together live in this protected space — without the need to distribute files ahead of time.

HULLFISH: What are some of the tools that you have? Can you draw on the for example?

BARTON: So we already covered the recording, which for me was one of the biggest features, but soon we’ll have the ability to take pieces of those recordings and allow other people to have access to them. For example, let’s say that you and I are in a visual effects review and the director says, “By the way, I have a music note for this scene. This part of the cue isn’t quite hitting the tone I want.” So at the end of that session, you can go back to that recording and select any portion of it, then give access to any authorized users of that room which could include the Music Editor or Composer. In the world I tend to work in, there are hundreds of notes to distribute to several different vendors after a visual effects review. Often this requires translation and interpretation. Imagine if the animator (who wasn’t part of the review) could watch the Director give notes on their shot — flipping between watching the Director’s webcam and the content being streamed. We’re attempting to remove all that stands between a Director and the person who’s doing the work so there’s absolute clarity on what the note is, which we think increases efficiency by reducing the number of iterations.

HULLFISH: Oh yeah! Absolutely!

BARTON: Then, of course, you can draw on the screen, but unlike the other platforms, you won’t have to upload all the files first, since we’re a live collaboration platform.

HULLFISH: One of the things you kind of alluded to was the security issues. Some people might not realize it, but unless you’re working at a studio, the studios are really critical about needing all of their vendors and crew to be in a facility that has these kinds of door locks and there’s no access to the Internet and other security precautions. Facilities have to get certified for these specific security protocols. Tell me a little bit about the security and a little bit more about how that got approved by a bunch of studios.

BARTON: When I finished my tour of duty on Godzilla, the impact Evercast had on me and my life was profound. I saw an opportunity to not only become part of a new company and exercise a different part of my brain but more importantly, I saw an opportunity to make a positive impact on the lives of my friends, my colleagues — who go through many of the same challenges that I do. I hear time and time again how much we all love this craft, but the lifestyle that comes with it is just getting too much…or maybe I’m just getting too old (laughs). Footage counts are skyrocketing, budgets and schedules are shrinking, studios are chasing tax rebates around the globe requiring us to leave home for months at a time, or longer. So I’m on board with any technology that pushes back against this trend to help us reclaim a little bit of our lives.

After working with Brad and Alex for six months, discussing ideas that would improve the platform, I approached them and said, “I really feel like I can open some doors for you guys with people I’ve worked for during the last twenty years.” Not long after, I invested money, took nine months off from cutting to introduce Evercast to the studios — becoming part of the team and was made co-founder. My primary goal at that time was getting Evercast approved by the studios from a content security perspective. So I walked Evercast into each of the studios beginning with Disney.

After working with Brad and Alex for six months, discussing ideas that would improve the platform, I approached them and said, “I really feel like I can open some doors for you guys with people I’ve worked for during the last twenty years.” Not long after, I invested money, took nine months off from cutting to introduce Evercast to the studios — becoming part of the team and was made co-founder. My primary goal at that time was getting Evercast approved by the studios from a content security perspective. So I walked Evercast into each of the studios beginning with Disney.

HULLFISH: It’s always good to start small.

BARTON: (laughs) Well, the film I had done before Godzilla was Pirates. (Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales (2017)) And of course Disney is conquering the world so why not? They were the first to see Evercast and their immediate reaction reinforced my own instinct on what this could potentially be. I remember this boardroom meeting we had. Their production technology department was there; post-production; visual effects; IT — there were probably twenty-five people in that boardroom when we demoed Evercast for the first time. At one point, the boss stood up and said to their team, “Guys, you may all have your own security issues, but this is clearly the way of the future so figure it out and get it done.” I just looked at my partners and thought, Wow! This really has an opportunity to change a lot of lives…and by the way, we now have a world-wide master agreement in place with Disney and all their affiliates.

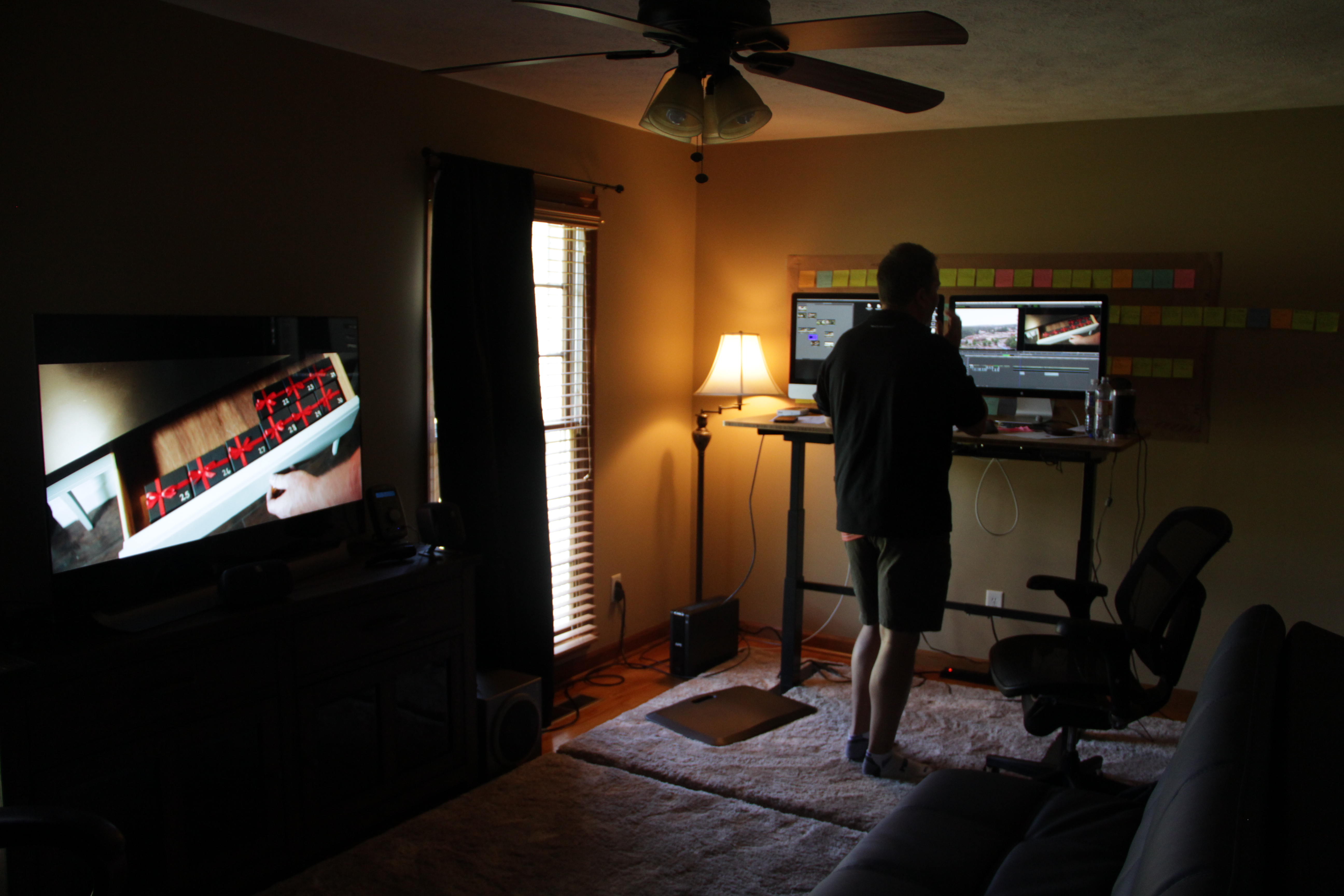

HULLFISH: I love the idea of just the quality-of-life issues. It looks like you’re in your home. Were you cutting with Michael in your home? Or did you just come back from the studio?

BARTON: One of the reasons I’ve worked for Michael on so many projects is that he never asks me to travel — so when I sign up, I know I’ll be in town for the next calendar year. Don’t get me wrong, I absolutely love traveling, just not for months at a time without my family. Not to mention, Michael’s cutting room is in Santa Monica, so it’s a 10-minute drive from my house.

HULLFISH: Do you know Alan Bell? He has cut some very big films and decided at the top of his game to move to New Hampshire, but he still wants to cut movies — just not in LA.

BARTON: Alan is my hero because he’s attempting to create the life he wants without sacrificing his career. Total trailblazer. I did a demo for him nine months ago — before he moved back east — and he was excited about the possibility of using Evercast to edit movies from his house. We’re continuing the discussion and it’s just a question of finding the right fit.

This raises the issue of our pricing model which is currently based on a flat rate — and it enables anyone on the entire production to use Evercast for as long as they want with no restrictions or recordings. We provide a virtual room that anyone you approve can enter. For this room, the flat rate is $999/month which breaks down to $250 per week and for that price, you can literally have anyone in visual effects (not including vendors), editorial, music, sound or casting using the platform. We have people doing production meetings, table reads editorial and VFX reviews, sound spotting on the platform. In fact, just today there is a music video being shot where the director literally is directing on one coast while the shoot is happening on another as the live camera feed is streamed to the Director.

HULLFISH: The production of movies including VFX and editorial and music and graphics design does seem to be increasingly international. It’s been that way for a while, so it seems that no matter what you’ve got somebody in L.A. and somebody in New York and somebody in London on every production almost.

BARTON: Yeah, especially with regard to visual effects. The vendors are now spread so wide across the globe. You’ve got WETA in New Zealand, ILM up north while MPC and Framestore have hubs in London, Vancouver, and Montreal. It’s all over the place. So Evercast is a way to keep everyone on the same page. In fact, on the film, I’m cutting for Michael right now — called Six Underground — our visual effects supervisor Rich Hoover is using Evercast about four or five hours every day reviewing shots with all of our vendors including ILM.

HULLFISH: I love the transparency of letting all those things flow directly from the director to the actual end person because normally it is through layers of other people. The VFX supervisor and you are sitting with the director and then you guys get all those notes and those go to the local VFX producer and down through supervisors to the end animator or compositor and somewhere along the line something gets lost in translation.

BARTON: It happens to me all the time in visual effects as shots come back wrong, but I’m guilty of it as well. In the past I would scribble down notes on a yellow pad and then I’d try to read them the next day and the pages would be full of sentence fragments because sometimes the directors are moving so fast, I don’t want to stop them for clarification because they’re in the flow. So I do my best guesswork the next day, which is not always accurate especially when I don’t have a photographic memory.

BARTON: It happens to me all the time in visual effects as shots come back wrong, but I’m guilty of it as well. In the past I would scribble down notes on a yellow pad and then I’d try to read them the next day and the pages would be full of sentence fragments because sometimes the directors are moving so fast, I don’t want to stop them for clarification because they’re in the flow. So I do my best guesswork the next day, which is not always accurate especially when I don’t have a photographic memory.

HULLFISH: You think of something like a director giving notes and he makes a hand gesture or uses his hands to show the interaction of two objects. There’s no way you can translate that to the VFX guys — especially directly to the end worker who’s executing the shot — but if you can send that little video to him, he’ll totally understand what he’s supposed to do.

BARTON: Right. And so that probably removes two or three iterations to get you to where the director wants to be. I see that time and time again. If I had a nickel for every time I’ve heard, “That’s not what I meant,” I’d be a rich man. Even in editorial, often I’ll make a change convinced that this is what the director had in mind only to run it for them and hear them say, “That’s interesting, but no. That’s not what I meant. This is what I meant.” Having a recording of the session ensures everything is done right.

HULLFISH: It sounds like a great platform. I don’t do gigantic movies like you do — the biggest of the big — but $250 a week seems incredibly reasonable even for the lower budget films I work on.

BARTON: Well when you spread it across all the departments who have access to it, we feel it’s literally giving it away. And I get that there are smaller budget projects where there might be a reaction to our flat rate but I think those are the projects who benefit the most by avoiding all the travel for the editor, the assistant editor which include flights, per diem, hotels, cars — not to mention the lifestyle issues that we’ve been talking about.

We also realize as a company that there’s a huge market to reach with all the individual content creators out there — the YouTubers, the people who don’t have a studio behind them, so what we intend to do is, in the in the months ahead, release an Evercast lite version that removes some of the security protocols that we’ve spent a tremendous amount of resources towards. And by removing those, we think we can lower the price to reach all of those individual content creators which then makes this the same user experience available to just about anybody.

We also realize as a company that there’s a huge market to reach with all the individual content creators out there — the YouTubers, the people who don’t have a studio behind them, so what we intend to do is, in the in the months ahead, release an Evercast lite version that removes some of the security protocols that we’ve spent a tremendous amount of resources towards. And by removing those, we think we can lower the price to reach all of those individual content creators which then makes this the same user experience available to just about anybody.

HULLFISH: You mentioned that with a VFX guy, it might save him two or three iterations. That’s a week of work for one person depending on the shot.

BARTON: It certainly is.

HULLFISH: I go on location sometimes but a lot of times a director will deliver the entire dailies “dump” at the end of the movie or may be delivered in two gigantic chunks and directors just say, “Hey, you’re you’re on your own.” And I would love to be able to offer this solution to them.

BARTON: Do you do your work from home?

HULLFISH: I do minor editing work at home, but I have an office about 20 minutes away with a big sound system and big monitor and a standing desk and an Avid NEXIS Pro. I have two systems there, so I can have an assistant there. When I’m at home, I’m working off a MacBookPro and headphones.

BARTON: I’ve tried to work from home and what I find is that I get so distracted during the day that I end up working until 3 or 4 in the morning to make up for all the time that I just goofed off!

HULLFISH: I can relate. Since you were committed to being home with your son before you really knew about Evercast, were you planning — on Godzilla — to try to use some other system?

BARTON: I didn’t have a horse in the race. I just wanted to find whatever technology existed out there to improve my lifestyle and cut a movie I wanted to do, but do it from Los Angeles. That’s what started me down this path.

HULLFISH: I’m going to bring up a touchy subject which is this leads us down the road to outsourcing editing to India and China or at least some English speaking country with a lower cost of living. Obviously, I believe that the editor’s position requires things that can’t be outsourced — it’s a relationship that is important to the director — but can we talk about that elephant in the room?

BARTON: I don’t look at what we do — what we have to contribute — as something that can be outsourced so easily, like a rotoscope artist or a compositor who doesn’t have that intimate relationship with the filmmaker. For that reason, I think we’re completely protected as editors because of what we contribute to the process. That’s my personal opinion.

HULLFISH: You could say this allows me to get Alan Bell who just wants to cut a movie in his home and as long as I’m willing to do it through this medium, I can get this great editor.

BARTON: And that makes me really happy. I think that’s to be celebrated — that people can make personal decisions about whatever is best for their family and still have a career.

HULLFISH: With the cost of living in California or New York, I’m sure more and more of us are probably thinking, “Alan’s got a good idea.”

BARTON: Oh, it’s been on my mind for a long time. I’ve seen other people do it with varying degrees of success. I’m wearing my Oregon baseball hat as you can probably see. I’m from the Pacific Northwest and I have a love-hate relationship with L.A. I love the people I’ve met here — my close friends and family are here — but if I didn’t have to live here, I’m not sure I would.

HULLFISH: I’m interested in the transition that happens once the director comes off the production end and is free to be with you side-by-side.

BARTON: I’ll give you a good example of how it continued to be used after production on Godzilla. I got into a rhythm with the director where he would check in with me from his house in the morning and I would show him what I was working on. Then he would give me notes which I churn through so that by the time he shows up at noon, I already have them implemented. Evercast continued to allow us to push the ball down the field, even while we were back home, and it also meant that the Director didn’t have to be in the cutting room for 12 hours a day over my shoulder, which I greatly appreciated…just sayin’.

HULLFISH: Since this interview, I got a demo of the Evercast system. Here’s the video.

HULLFISH: I’d love to switch topics. I was looking through your imdb page and maybe it’s missing some early years, but it looks to me like you went straight to working on the world’s biggest movie. Your imdb page looks so improbable.

BARTON: (laughs), I literally did make the leap from That Darn Cat to Titanic. My friends make fun of me all the time.

The editor of That Darn Cat was really Richard Harris who was one of the principle editors for Jim on Terminators and True Lies so when Jim was looking for someone to run the cutting room on Titanic, Richard was one of the people he reached out to — and because we were finishing That Darn Cat, Richard said, Oh my God! You’ve got to meet Roger…he’s a bit of a geek which is exactly what Jim needed at the time to manage that film, and so I was given this incredible opportunity to make this quantum leap into a world I probably had no business being in. But, I think my career is marked by those moments where an opportunity presents itself and I’ve decided to jump and hope the net appears below me.

I constantly put myself in situations where I’m uncomfortable because I feel like that’s when we grow as people or as artists. That was certainly a big opportunity for me.

I constantly put myself in situations where I’m uncomfortable because I feel like that’s when we grow as people or as artists. That was certainly a big opportunity for me.

I’ll give you another example on the same film where I took that leap. At that time, I was simply hired to run the cutting room because It was Jim’s intention to cut the movie by himself. As the weeks went by, I’m working at his house in Malibu and the footage is just piling up – mountains of it. Three or four weeks into the process, I can not imagine Jim catching up to the amount of footage he’s shooting, so I see an opportunity. I called the producer, John Landau, and said, “Listen. I’m not sure how you’re going to make your release date if Jim cuts this himself, so, if you’d like, I can start assembling this into some shape that Jim can at least work from, so he’s not starting from scratch. I can find someone to replace what I do — running the cutting room.” Afterward, there was a long silent beat on the phone and I’m sitting there with gritted teeth, waiting for his answer. And he says, ‘Ok kid, let me let me talk to Jim about it and I’ll get back to you.’

So the next day John calls me and says, All right. It’s a green light. “Go ahead and start cutting, and find your replacement.” So, for the next month, I was alone at Jim’s house, cutting together many of those scenes that were recut of course by Jim, Conrad, and Richard. But, to be sitting in there for that month, cutting that movie on my own, I kept looking behind my shoulder saying, ‘How the fuck did I get here?’ Thankfully, it seemed to work out, okay, because I had worked under some really talented editors up to that point, and I paid attention, so when the opportunity came, even though there was some fumbling around and experimentation, I felt like I could at least show Jim something that reflected the material.

And ultimately that’s how I met Mark Goldblatt. Because at Jim’s Christmas party, he ran a few scenes for his friends and amongst those cut scenes were things that I had assembled, and Mark took notice of it, asked Jim who had cut it, and Jim sort of reluctantly turned his head to me standing in the corner. That was my introduction to Mark Goldblatt. He was looking for an assistant while he was cutting Armageddon for Michael Bay, so I literally jumped from Titanic to Armageddon, where I assisted Mark, and had the best film-school experience you can possibly imagine by sitting behind him for twelve hours a day while watching him cut. Mark Goldblatt is one of the most incredible, generous human beings I’ve ever met — he’s also the most talented editor I’ve ever met and is responsible for my career. Mark taught me not only how to edit, but how to be an editor.

HULLFISH: That’s a really unusual position for an assistant editor to be in. What were your responsibilities besides acting as a second pair of eyes in the cutting room? That’s just not what any assistant editor I’ve ever heard of does — to solely give feedback on edits “live.”

BARTON: I was a sounding board for him.

HULLFISH: I’m shocked that someone pays an assistant editor to act solely as a sounding board. Many people use their assistant editors as sounding boards but it’s only after they’ve done the syncing and all the other stuff.

BARTON: Well, some of the other assistants were a little pissed off that my entire job was to sit in there with Mark while they were out syncing dailies and doing a host of other things to run the cutting room. I had no idea what I was walking into but quickly learned, I was there to support Mark in whatever way he wanted me to. It created a little tension in the cutting room, but Mark also worked twelve hours a day from 11:00 a.m. until 11:00 p.m. And when he left, he would typically leave me two to three hours of sound work to do that I had to have ready for him in the morning. So not only did I have to be there before he showed up, but I had plenty of work to do once he left after I’d been focused in his room for twelve hours a day.

HULLFISH: So you weren’t just sitting in the back, but that is still amazing. Did he teach you by saying, ‘Here’s what you do?’ Or were you just in the room and you got it through example?

BARTON: Everything he taught me was by osmosis. I was lucky enough to be in that position — to sit with Mark and provide an opinion — for whatever that was worth. But the benefit to me was understanding his workflow and watching him work the footage over and over and over again – each time elevating the film. Mark accomplishes this in part by building out select rolls that allow you to frequently revisit the raw footage in an organized and efficient manner. Watching him build these reels allowed him to understand the Director’s intentions and how they might have changed over the course of each setup. Revising these reels allowed him to constantly come up with new solutions to support new ideas. It really spoke to both by right and left brain and I’ve used it ever since, whether I’m cutting an intimate dialog scene or gigantic action set piece.

HULLFISH: You also mentioned that you do a continuous process of select rolls. What are you doing once you’ve made a selects roll for a scene? What changes are occurring to the selects roll through the process?

BARTON: Well, the reel is so important to me that as new footage comes in — before I do anything else — I will fold that into the existing select reel as if it was all shot on one day. So going back to that represents the entire scene.

For me personally to load every clip individually whenever there’s a new idea — it’s really arduous and not creatively what appeals to me. By having done the heavy lifting early on and organizing the footage in a sequence that represents all the usable footage — I feel like I can go back into a select roll and very quickly come up with some options rather than going to hunt for it in this enormous amount of dailies that might be spread across 50, 60, 70 clips.

HULLFISH: The reason why I asked it was because some people will make multiple selects reels where they’ll whittle it down even more or they’ll maybe have an assistant cut a reel for the scene of only a selection and then they’ll go you know. Now I just want to act sometimes as an assistant make me a selects reel of nothing but reactions of “Joe.”

HULLFISH: The reason why I asked it was because some people will make multiple selects reels where they’ll whittle it down even more or they’ll maybe have an assistant cut a reel for the scene of only a selection and then they’ll go you know. Now I just want to act sometimes as an assistant make me a selects reel of nothing but reactions of “Joe.”

BARTON: To each his own. Everyone has their own process and I would never criticize someone else for theirs, but for me I feel like I need to run the footage through my hands as often as possible. So when it comes to finding material — whether it’s a master, a reaction, or a close-up or a dynamic effects plate, I feel like that’s where the creativity lies. And I think in that process of scrubbing the footage, a whole host of other questions might be answered or a possibility might be presented.

HULLFISH: And how granularly are you breaking your selects rolls up?

BARTON: I wish I could tell you there’s one rule, but it’s an intuitive process that changes each time I seem to do it. Also, I don’t want to break apart the film too much, otherwise I won’t see the possibility of just sitting on a shot that works great without cutting.

HULLFISH: That’s exactly my point.

BARTON: Often, if I’m looking at a master that that tells the story or reveals geography through an interesting camera move — I’m paying particular attention to those and making sure that they exist in a long section even though they might encompass several lines of dialogue. In fact, it might encompass a quarter of the scene. The length of the select roll doesn’t matter to me at all. So if it’s a four-hour select roll, I have no problem with that, because normally I’m scrolling the reel to at least park myself on the section I want to run. Then I sort of break it down into the medium shots where I might play two or three lines of dialogue — still looking for when I can hold it longer — but when I get into the close-up coverage that’s when I start to cut it up more so than I would otherwise. It’s really important at that point — when I’m breaking up individual lines of dialogue that I am also cutting into my select roll any reaction shot I feel might tell the story in another way — in a more powerful way. I’m a big fan of reaction shots.

HULLFISH: You mentioned that one of the things you learned from Mark Goldblatt was the process of going over and over and over and redoing things. And if you weren’t in the room with him you might just think, “Oh he’s a brilliant editor and he cut it like that the first time he laid it out.” The only way you knew how he ended up at a scene was because you were there the whole time to see that it was a process, and not “one and done.” It reminds me of a story from a documentary about the Eagles where Jackson Browne lived upstairs from the Eagles and so they heard him writing songs and they could hear that the songs didn’t come out fully formed. He needed to work them and revise and edit and it was a PROCESS.

BARTON: I had a similar experience on a film where we considered folding elements of one of my favorite bands’ new album into our score. On paper, this was the coolest idea ever! We flew to meet the band and they handed over sketches for their new album which I was SO excited about. The next day I plugged the drive in, listened to the tracks and thought…”you’ve got to be kidding me?” Unfortunately we couldn’t see past these sketches so we passed on the opportunity, then months later the album came out and guess what…there were some amazing tracks! It’s a process.

How each of us gets to a locked picture may vary wildly, but in my experience it’s usually a very long, drawn-out process where you feel at times, “this scene can’t get any better” and then the pizza delivery dude sees what you’re working on and offers a new idea that makes you think, “why the hell didn’t I think of that!?” (laughs) I’ve worked on lots of films requiring multiple editors and sometimes you lean out your door to hear someone else working on the same scene as you. We all need strong opinions as editors, but I do my best to separate my opinion from my ego — it’s a work in progress, but I’m working on it because even without multiple editors, we’re ultimately there to support someone else’s vision: the director’s.

I really appreciate the way that Kevin Feige, Jeff Ford and everyone at Marvel works because they really seem to support and promote “the best idea wins” approach because it really does take a village to make the best film. As much as filmmaking is about presenting a strong point of view, what we do is inherently subjective. I believe editors do their best work when they make strong choices, but that doesn’t mean those choices are the only way the scene or sequence works — and to top it off, because the entire experience is so fluid, what works one week may be undone by a change in the previous reel this week. This multi-faceted puzzle is why I love what we do as editors.

HULLFISH: You have worked on more massive projects than just about anyone I’ve spoken with. How different is it in terms of process to work on these enormous films than something smaller? What kind of project management is layered on top of your creative skills? Or is all of that stuff on post producers or assistant editors? What would surprise someone like me, whose films are smaller, about working on something massive?

BARTON: With regard to the crew, it’s a matter of scale. Often, on the big films, you’re describing, just about everything is amplified, including expectations — so the pressure is real but no more real than those working on smaller films who are doing more with less.

For me, I try to stay focused on the storytelling and hire people who are far more adept at running the room that I am. I used to be that guy so I have pretty intimate knowledge about workflows, but the technology has ironically passed me by. Now I try to stay in my lane — focused on the creative end of things while keeping an eye out for the warning signs that a problem is heading our way.

HULLFISH: You’ve been fascinating to talk to. Thank you so much for your time — plus your wine’s almost done. I’ve been watching your wine glass get lower and lower and I figured, “When he hits the bottom it’s over.”

BARTON: (laughs) I love working with Michael. He’s been incredibly loyal to me over the years, but sometimes, when I come home, this glass of wine is absolutely essential. And by the way, he might feel the same way about working with me all day!

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now