Art of the Cut is brought to you by our friends at Frame.io.Video collaboration for the 21st century Read all of the AOTC interviews or learn more about Frame.io |

Barry Alexander Brown started in film as a director, and his first documentary, The War at Home, was nominated for an Oscar in 1980. He was also nominated for an ACE Eddie for editing Madonna’s Truth or Dare.

Though he has continued directing his own films – and has edited for several directors – his most notable work has been as the editor in one of the long-standing director/editor relationships, with Spike Lee.

Together, they have worked on She’s Gotta Have It (with Brown as sound designer), Do the Right Thing, Malcolm X, Crooklyn, He Got Game, Summer of Sam, The Original Kings of Comedy, Bamboozled (with Brown as Additional Editor), 25th Hour, She Hate Me, Inside Man, Miracle at St. Anna, Passing Strange, Bad 25, Oldboy, Michael Jackson’s Journey from Motown, and their latest collaboration, BlacKkKlansman.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: I saw BlacKkKlansman last night. I loved it. The theater was full and the audience was into it.

BROWN: Oh good.

HULLFISH: On She’s Gotta Have It, Spike is credited as the editor and you started as a sound designer?

BROWN: That’s the credit I got. If you look at She’s Gotta Have It, there’s no sound design to it. Spike liked this title. He liked the whole idea of sound design. I knew how to do a cue sheet because I’d been working in documentaries and editing my own documentaries and I knew the basic stuff about tracks. This was back when we were cutting on film. I also recut one scene in that movie. A scene where Nola and Greer are in bed and they’re having sex, the camera looking down on them. Spike had done something in camera that he thought would work and he didn’t think it worked, so he said, “Can you give it a try?” And I did.

Spike was a good friend of mine already in 1985. And he asked me to work on it and I was willing to do anything because somebody I knew was making a feature-length movie.

HULLFISH: How did you meet?

BROWN: We met in the summer of 1981 in Atlanta, Georgia where I had gone to research a project. I’m from Alabama originally and I made my first film called The War at Home and it got nominated for an Oscar for documentary. A friend of mine had gone to Morehouse with Spike. They were classmates and they were working that summer with high school students doing a magazine show for cable. Spike and I met and when both of us returned to New York in the fall, I was President of First Run Features and we needed somebody to do part-time work setting up the prints: making sure the prints were clean and in order and everything. This was on 16mm at that time. I thought this is a great part-time job for a student, and Spike was at NYU which was only a few blocks away. So over the course of the next few years, we got to know each other. I think he was making a hundred dollars a week and as president, I was making two hundred dollars a week. We were not getting rich.

HULLFISH: So your editing came from the documentary side of it?

BROWN: Absolutely. I was doing my own editing because I couldn’t afford an editor and even on the films where I didn’t take credit for the editing, there was a lot of editing I did on them. I just didn’t feel confident to take the credit.

Spike had kept a diary during She’s Gotta Have It and used it to write a book on the making of the film. I was reading the book and it said, “Barry’s going to edit my next feature.” And that’s how I found out that he wanted me to edit. He never said to me that he wanted me to edit. I really wasn’t an editor. I really didn’t consider myself an editor. It took me years actually to consider myself an editor. I did School Daze, which was Spike’s next film and then my friend Mira Nair asked me to do Salaam Bombay, her first feature. And right after Salaam Bombay, I did Do the Right Thing. And then I did Madonna’s film, Truth or Dare. (which was nominated for an ACE Eddie for Best Editing). So all the way through that I just kept thinking that somebody — a producer or somebody from the studio — would figure out that I am not an editor. I don’t think it was until I did Malcolm X that I thought, maybe I am an editor.

HULLFISH: What do you think you brought over from documentary to feature dramatic films?

BROWN: My mentor in those early days was Emile de Antonio: the great American documentary filmmaker — Point of Order, America is Hard to See. He would say that there isn’t really a huge difference between documentaries and narrative films. You still have to do all the same things. You still have to create characters. You have to have emotional arcs. You have to have a storyline. You have to have a plot line. You have to keep it moving. So I’ve kind of approached documentaries in that way. I didn’t do documentaries out of some enormous love for them. It was because I had the opportunity to co-direct that first film and I jumped at it and did it. And in the course of that, de Antonio became a mentor. I looked at it in a similar way.

Obviously, the difference is that you’re dealing with things that truthfully happened in documentary and you’re using interviews to cover the story. But no matter what, you’re introducing characters and trying to keep the audience interested and trying to keep the audience cued in to where the story is going and not lose them. My years in documentaries served me very well in the narrative field. At the same time, I’ve always been a reader, and my love for the novel probably influenced me even more in terms of storytelling.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about some specifics in BlacKkKlansman and I’m hoping that the answers to specific things will reveal some broader editing truths. Tell me about the coverage in the opening interview scene with Ron Stallworth trying to become a police officer. In the film, as released, there are only two static set-ups for that scene.

BROWN: There is no other coverage. That’s the way Spike saw it and shot it. Interestingly, those lock-offs were shot simultaneously.

HULLFISH: Oh that’s interesting, because they’re both shot looking directly into the camera.

BROWN: There is one camera that was looking at the police chief. And one on Ron and that’s how they did it. And that scene begins with a lengthy hold where they’re just looking and not talking at all. And I remember we were in dailies looking at that shot and Spike says, “I want this shot to start from the point where I say ‘Action’ to the time they deliver the first line. I want that whole shot.”

HULLFISH: I remember that long hold. I loved it. The director has a vision and one way that he can make sure that he gets his vision is to not give you any other options.

BROWN: That’s the famous story of John Ford. The studio criticized him for only shooting certain lines. They told him he had to shoot the whole scene. But when there were parts he didn’t want used, he’d put his hand in front of the lens. The actor would deliver the line he wanted, then Ford would put his hand in front of the lens.

HULLFISH: There’s a great little montage — almost documentary style — of some trees that give the audience just a little space between scenes. One of those things that I love is not just the pace of an individual edit, but the pace of the whole film and saying, “Hey, the audience needs a second to breathe or switch emotions.”

BROWN: Absolutely. The other purpose of those shots in that montage was to keep you in mind of the place we’re in. We’re in this particular town of Colorado Springs. We kind of wanted to keep grounding you in that way as well as — you’re right — giving you time to shift the gear and to breathe a moment.

HULLFISH: The other place where I love the editing was during the Kwame speech. So much of it is played on reactions. What were some of your triggers to when you decided to be on Kwame and when you wanted to be on those reactions?

BROWN: Spike shot the portraits at the same time he shot the Kwame speech. They were just shooting them in a different room and Spike was choosing people that were in that audience. He had this notion of, “I’m going to use them. I’m not exactly sure how I’m going to use them, but I want to use them.” He chose the first place where the first portraits came in. And then left it up to me as to where anything else would fall afterward. A lot of that stuff just came down to feel. I’m a very instinctive editor and so much of this is just feeling such as which faces do I want to marry together.

HULLFISH: For those who haven’t seen the film, there are traditional reaction shots of people in the crowd listening to the speech, but then there are these “portraits” which are really interesting, kind of stylized visually. I would think you have to go to those fairly soon in the speech so that you’re not surprised by them.

BROWN: It doesn’t come too early. I’m with you. My instinct would be to make it a tiny bit earlier, but Spike had a really particular spot that he wanted It to start.

HULLFISH: There was a section in that speech which I wanted to ask you about: was it scripted – or something that you created editorially – when Kwame says “kill him” and it’s repeated three or four times.

BROWN: I think he said it a couple of times and then I repeated it. I loved what Corey Hawkins was doing there. I loved the intensity. Maybe it was even Spike’s idea. I can’t remember how that came about. It’s just a moment where you can take somebody’s performance from more than one take because it’s so good. You rarely can do it, because it feels like a repeat, but there it builds.

HULLFISH: Yeah I loved it. I was telling you how much the audience enjoyed it and there was a lot of laughter. It’s a film that makes you think, but it’s also very funny — typical of many of Spike’s movies, I think. Did you find that after screenings you had to open places up to allow for laughter? So the audience doesn’t miss following lines?

BROWN: We didn’t do any screening.

HULLFISH: No screenings!

BROWN: No. But we pulled back on the humor heading towards the end of the movie. We took some things out that were funny because it was hurting the tension and the drama towards the end of the film.

It was quite remarkable that we had not one single preview screening of the movie. Also, there was no time. We were really racing towards getting the film ready for Cannes. We were hoping we would get into it and we did. I don’t remember the last time we didn’t do a screening for a movie. Probably She’s Gotta Have It in 1985 or 86. So this is really, really rare — incredibly rare.

HULLFISH: Please don’t take this next question as a criticism, but merely just an exploration between two editors. There’s music before the first meeting between the undercover cop — Zimmerman — and the KKK that’s very foreboding. Is it bad to lead the audience or telegraph to the audience what might happen in a scene?

BROWN: The music is 100 percent Spike and nothing really bad happens in that scene, actually.

HULLFISH: But as an audience, you’re thinking something’s going to go wrong.

There are a couple of nice pre-lapped audio segues between scenes, and I think even a post-lap of audio. What’s your feeling about those types of transitions? Just a way to do something different?

BROWN: I think it’s really, really good to mix it up. Sometimes it’s playfulness and sometimes it’s just, “Where’s this coming from?” I’m a big believer in mixing things up. Some of that stuff for me is just being cinematic.

HULLFISH: There’s such a nice variation or dynamic in the pacing. I always think of editing like music that needs fast sections and slow sections.

BROWN: It is. You’re absolutely right. It is music. You really know your shit. I’m impressed. Movies are like a symphony and editing is definitely music. Someone asked me why the Kwame Ture speech works so well, and it’s rhythm. Obviously, Corey is great and really delivers something fantastic but beyond that, you’ve got to keep a certain rhythm going.

HULLFISH: You’ve got natural rhythms where you feel like people are speaking in the rhythm they should be speaking (even though we know that you’re creating those pacings through editing), but then there are other places where the rhythms are faster, un-natural – stylized. I’m thinking of the scene where the KKK guys are saying, “There’s niggers selling soap. Nigger selling automobiles.” Talk to me about why you decided to break from the natural rhythms of speech.

BROWN: All of a sudden they’re speaking almost as a chorus. And they’re all repeating the same words. On some level, it’s kind of musical. There’s certainly a playfulness on my part there. It’s not a natural moment: certainly not part of a conversation or a dialogue. It becomes something else at that moment: a motif.

HULLFISH: The other pacing thing I loved was a longer held moment where Zimmerman is describing his Jewishness or his lack of Jewishness. Then you kind of let things slow down.

BROWN: Yeah! Really slow! We just stayed on that low shot for such a long time, but really so much of that is that — especially in that one take — Adam (Driver) had just found something so incredible. Every once in a while you come across a take and a moment where an actor is giving so much and to cut away from it is just criminal. I remember seeing that in dailies thinking, “Wow, this is powerful.” When that happens, you just don’t get in the way. You’re trying not to get in the way sometimes as an editor.

HULLFISH: Amen.

BROWN: That was just a gorgeous performance.

HULLFISH: He’s really considering his life and who he is. It seems like it’s the first time he’s considered it at that moment.

BROWN: And Adam captures that so well.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about intercutting between storylines or things happening simultaneously.

BROWN: You’re talking about that Waco, Texas scene where Harry Belafonte is playing Jesse intercut with the induction of the Klan members.

HULLFISH: Absolutely.

BROWN: The idea that they’d be intercut was definitely in the script, but the script had big blocks of dialogue, but I think Spike knew all along that they wouldn’t actually be cut like the script. Once they have it shot and I have the footage, that’s going to tell us where we can go back and forth.

We’d just find these places which were just right to be back with the Klan and just right to be with Harry Belafonte. And moments to marry them together where they really are one. Like when the character of David Duke is doing the holy water and Harry says, people came out and treated it like a 4th of July celebration. You’re watching these Klan guys staring down and then Harry says, “And all I could do was watch” and I cut to Adam as he looks up at David Duke. And then we go back to Harry and he says, “I could only watch and pray they wouldn’t find me.” I just thought that these lines played beautifully together because Adam is playing a spy in the midst of the Klan, praying HE wouldn’t get caught either.

HULLFISH: I also love the idea of the editor amplifying a big emotional moment. There is a point where Ron has a Polaroid camera and wants his picture taken with David Duke and another Klansman. Just as the picture gets taken he throws his arms around the two Klansmen and it seemed like you amplified the surprise in that moment through editing.

BROWN: The thing I did was – there’s a cut to an extreme close up of the Polaroid camera flashing. And the shot of the Polaroid itself. All that really helps you to amplify it. That was an incident that really happened.

HULLFISH: I gotta see that Polaroid.

BROWN: He lost it in a move.

HULLFISH: Oh that’s terrible.

You mentioned that Spike chooses a lot of this music. One of the places where I love the transition was — I’m not going to give away any plot points — but there is an explosion in the film. And then you cut to the very peaceful Emerson Lake and Palmer song, “Lucky Man.” It kind of goes from this incredibly tense moment to this moment of release.

BROWN: For sure. You’re right.

HULLFISH: And then again with the idea about amplifying moments or not worrying quite exactly that you’re dealing with complete reality: there’s at least two places where I noticed a doubling of action. One is, there’s a double hug at the end of the film and there’s also a double phone hang up at the end.

BROWN: This double thing: it comes from the very first time I cut anything for Spike on She’s Gotta Have It. It started as a joke. When I was cutting that very first scene, I noticed that they had two takes of Greer taking off his clothes and getting into bed with Nola. I said, “These are so similar, but a little bit different — a little bit off.” So to make Spike laugh, I had Greer get into bed twice. But it was a joke. Spike laughed, but he said, “I love this. We’re keeping that in.” From that moment on, there are moments in almost all the films we’ve done together where we do double cutting.

HULLFISH: I have two questions about sound. One is: the dogs barking behind Patrice leading and Ron up to the cross burning. Obviously, it was added in post, but was it actually scripted? Or was the idea of dogs barking derived during the edit?

BROWN: That was actually brought in during the mix. Spike came up with this idea about the dogs barking. They were bloodhounds. The kind that might chase people down.

HULLFISH: That’s what it sounded like to me.

BROWN: That was all Spike and during the mix he just kept adding it in more and more places.

HULLFISH: The other place was that during Kwame’s speech, there’s kind of a gospel call-and-response thing going on where he’s saying stuff and the audience is responding. Were all those audience responses added in during the cut or the mix or live?

BROWN: That was the crowd there. We augmented some of that, but most of that was the audience right there when he gave that speech. The audience was into it. So when you hear a woman scream back, “EDUCATE! EDUCATE!” that was just there. Corey had them into it.

HULLFISH: That’s awesome. Having cut a lot of films in the 80s and 90s, you were obviously a guy who started cutting on film. What did you use and when did you switch to digital and how did that go?

BROWN: I cut on a flatbed Steenbeck. Spike and I both went into digital kicking and screaming. We wanted to stay on film and we came into digital very, very late. I think maybe 25th Hour (2002) was our first film that we did digitally.

HULLFISH: That’s a good six or seven years after many people in New York and Hollywood had switched to digital.

BROWN: We just went kicking and screaming. We didn’t want to do it, but then it would have just been so hard to complete the film because of the delivery process for sound editors.

HULLFISH: Have you been on Avid ever since, or something else?

BROWN: Avid ever since and I love it.

HULLFISH: What is your approach to a new scene — a blank timeline?

BROWN: Some of the ideas come from watching the dailies with Spike.

HULLFISH: Could you comment on any of the following film clips?

BROWN: Ah, yes, the America First toast. It feels so much like something that is probably going on somewhere in the US right now. Basically, it’s the B Side of Make A America Great Again. It’s one of the few moments where the movie really takes the audience into a behind-the-scenes view of the ultra-right and their coded messages. I mean, what does America First even mean? I think we know they are not talking about America, they are talking about white America.

BROWN: For one, the scene is necessary to just get through the business that “Ron Stallworth” has been invited to join the klan. The interesting part of the scene is the implied threat behind Felix asking Flip if he’s Jewish. Ironically, Flip is Jewish and that leads right to that moment we talked about earlier where Flip talks about his being Jewish as he stares at the KKK membership card that this scene sets up.

BROWN: Fascinating conflict between Ron and Flip and shot very simply. As an editor not much to do here but keep the pace up – it is tight. The feel has to be Ron doesn’t let up and Flip is on the ropes. One of my favorite moments in the scene is the sound of the cigarette lighter opening and the flame igniting as Flip walks into the shadow and Ron is left standing in the wide shot with a single line “Right partner?”

BROWN: As an editor, I am doing absolutely nothing here – just sitting back and watching terrific acting and directing. I love the flirtation that is going on while they are talking about Kwami Ture. One can really feel the chemistry between Ron and Patrice, feel that immediately these two people are very attracted to each other and yet nothing flirtatious is said in the entire scene.

BROWN: For Spike and myself, this took us right back to Malcolm X and it was such a joy to be back there, a place I never thought I would be given the opportunity to revisit. Corey Hawkins is so good here. The way he delivers, “It is time to stop running away from being black.” It was an echo of Malcolm and an echo of the early Stokely Carmichael who would preach on college campuses in the South “Black is beautiful” to shocked crowds. The speech was so authentic and inspiring. I think that’s why it worked so well and why we could keep it at the length it is in the movie.

HULLFISH: Thanks so much for your time.

BROWN: Great interview. Thank you.

For more exclusive content from this interview, go to the FrameIO website.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

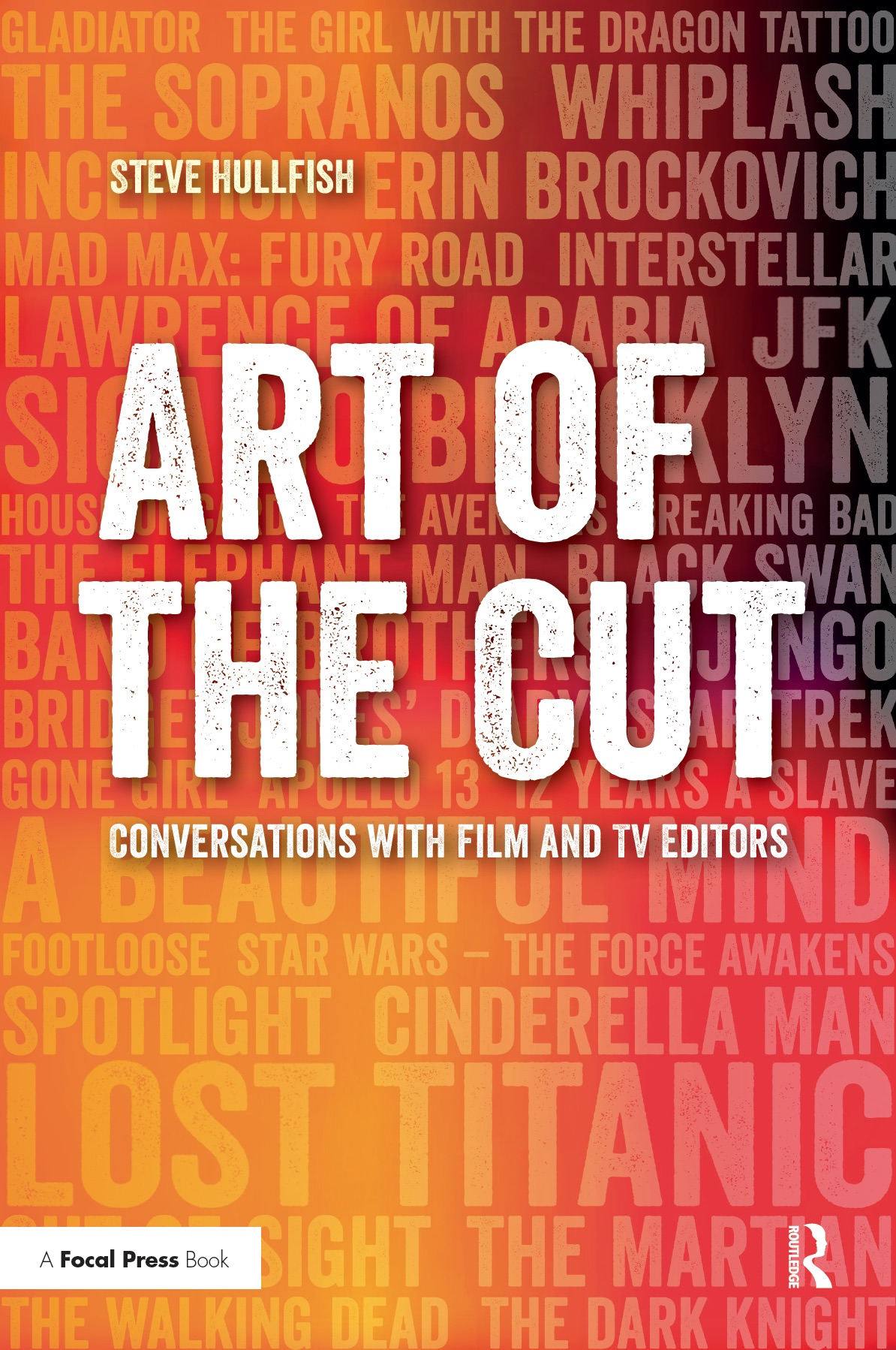

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now