In this interview, I’m talking with the core editing team of the Amazon TV series Bosch – which just finished its sixth season.

Joining me in the conversation are Jacque Toberen, Kevin Casey and my long-time friend, Steve Cohen, ACE. (Jacque is pronounced as “Jackie” and Toberen is pronounced tuh-BARE-in)

Steve was one of my first “internet mentors” in the early days of Avid. His book “Avid Agility” contains a lot of the wisdom he imparted to me back in the early 90s, and, of course, it’s been updated since then.

Steve was one of my first “internet mentors” in the early days of Avid. His book “Avid Agility” contains a lot of the wisdom he imparted to me back in the early 90s, and, of course, it’s been updated since then.

Steve’s filmography includes feature films, Rambling Rose, Lost in Yonkers, Angie, Blood and Wine, and 15 Minutes. Also TV including, Wayward Pines and The Bridge. He’s been very involved with the digital transition, working closely with Avid Technology, helping to start the editing program at the AFI and co-founding the Editors Guild Magazine.

Jacque’s filmography includes editing China Beach, 105 episodes of ER, Detroit 1-8-7, The Good Wife and Betrayal.

Kevin’s filmography includes Thirtysomething, Sisters, ER, Southland, Detroit 1-8-7, Boss and The Bridge. His work at ER earned him five Emmy nominations and one win.

This interview is available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven

HULLFISH: How do you three collaborate? Do you do any collaboration as a group of editors? Obviously you’re probably editing your own specific episode, but how are you working together as a group?

CASEY: We’re always saying, “Hey Jacque. Come in take a look at this.” Or Jacque says, “Kevin can you look at this?” We’ll go to Steve and say, “What do you think?”

It’s more just individual one-thing-at-a-time type stuff. If I hadn’t seen what Steve was working on and I was working on the next episode, I might collaborate in that way, saying, “I don’t know this person.” It’s a new character to my episode. We just look at individual pieces or scenes sometimes if we’re stuck.

COHEN: I think we actually collaborate more than we realize and we do it sort of unconsciously and subtly. We are all friends and we like each other and we’ve been hanging out for a while now and I think we just know how we think. We watch each other’s episodes. You have to. You can’t really do it if you don’t watch what came before and what’s coming after.

So even though you’re doing every third show, you have to see everything. You’ve read the scripts, but that isn’t enough. You want to see the show as soon as possible and I think that we all play off of each other. I think some of it’s unconscious. Some of it’s: “Come into my room and help me.” Some of it’s: “I want you to look at this. Do you think there’s anything wrong with it?”

We’re another pair of eyes for each other’s work. Also, I think on some deeper level we all kind of are playing in the same sandbox and we know it.

TOBEREN: We work through the stories. We talk about everything a lot, actually, because we eat lunch together and we’re always talking about the scenes and sometimes a character may appear in episode 1 and not again until Episode 5. And so we track all of that.

COHEN: Exactly. We talk about the show a lot. You can’t help but talk about the show a lot. It’s your life for six months.

TOBEREN: Plus, we do have the writers right there on site. And if we have a big question about where something’s going — because oftentimes we don’t know where something is going.

HULLFISH: You’ve got to rely on the showrunner for that, right? The subtext you need to put into something.

TOBEREN: Right. And there have been moments when they haven’t wanted us to know a specific thing until you know it was approaching that time to reveal it. That’s part of the storytelling with Bosch is that a little piece of information is revealed and then another piece.

COHEN: The stories are tricky. There’s a lot going on and there are different characters influencing each other and all kinds of pieces of evidence that are coming together.

TOBEREN: And that’s why we run in and say, “Can I see that scene? Did she say this?” Because there are so many little details dropped here and there and you want to track exactly where that piece of information was revealed.

COHEN: You want to track the emotional state of the characters to say, “This happened in the last episode which I didn’t cut, and this is his reaction.” It’s only a day later but it’s three weeks later in editing time.

CASEY: I do something that these two guys sometimes roll their eyes about, but I know Steve and Jacque, the second a script comes out — first draft — boom, they’re reading it. They’ll say, “Did you read the script for show seven?” I say, “No. No. I’m on show 4. I don’t care what happens in show seven.”

I like to take it as it as it falls in front of me. I don’t want to know too much, quite frankly, up ahead. So we differ in that way. I like to read the script that’s going to stage. That they’re going to shoot. That’s the one I want to read. But that’s just me. That’s the way I like to do it.

HULLFISH: To take it more as an audience would?

CASEY: I like to cut it as it comes to me. Hopefully, I cut it properly if it’s going to foreshadow something or whatever, but the way our show is done you’re going to do it right because it’s really shot well and it’s usually directed quite well, but I just don’t really care about three episodes down the line when I’m on my own.

TOBEREN: Steve and I always want to know what happens next.

COHEN: We want to know everything. The most important thing in the cutting room is having the perspective of the audience and none of us really have that. You can’t have that after… Your first read is your first read. Your first look is your first look. After that, you don’t have that kind of perspective.

TOBEREN: You gain a little bit when several months have gone by if you go back and watch Episode 1 through 4 or 5, perhaps. Then you’ve got it back to a certain degree, but you’re right. Once you know something that audience perspective is gone.

HULLFISH: It could color your editing, right? If you know, “Oh my gosh, in episode 7 this guy is going to betray this other guy,” so in Episode 4 now maybe you’d hold on some statement or the reaction to a statement a little longer because you know it’s a lie.

CASEY: Well sometimes both ways. I’ve cut it not knowing what’s going to happen. You cut it the way you think and then — down the line when you do find out what’s happened — you think, “Maybe I should re-examine that a little bit.” Maybe if I knew beforehand, I might have overdone it.

COHEN: The fear is that you overdo it.

CASEY: Yes. So I like to NOT know. And then — looking back at the show before it’s finished — Oh wait a minute. “Now that I see that, I really should hit that a little harder.”

For me — most of it — I just try to do it sort of instinctually anyway. Usually, it works. If it doesn’t, that’s the great thing about editing — “You can fix it.”.

TOBEREN: And that’s the beauty of our show. We’re able to go back into our shows and polish if we need to because we don’t lock some of the shows until usually November, or the end of October, right?

COHEN: Because everything drops at once there’s no air date. We can hold off. We have to finish shows for sound. It’s not like we can hold off on everything, but you can hold off more than you would on a network show where you have to deliver week after week.

CASEY: Yeah, I find If it’s on the schedule to deliver my cut to the director, I just go to Mark Douglas, who’s our post producer and I say, “I don’t think I’m going to get this by Tuesday.” He’ll say, “OK. How about Wednesday?”

We try to stick to schedules but we get some leniency at times which I like. It’s not tight, tight schedules that make us crazy.

HULLFISH: Since the shows kind of deliver all at the same time are you able to seed stuff back into earlier episodes or understand how a flashback is gonna play because you know what’s going to happen three episodes down the line?

COHEN: Yeah. I think that’s part of it. We can have a bird’s eye perspective and see an arc of several shows before we have to lock them.

CASEY: Well of course, once the producers get in with us sometimes that’s when they say, “This is gonna happen or that’s going to happen.” For the guys that read the scripts in advance, they don’t look stupid like I do but that’s what happens.

TOBEREN: Last year, the writers even changed the identity of someone that killed someone else because that affected me in the way that I cut this one character because originally it was going to have been him that killed this person but it ended up being someone else.

Because I thought having him be too angry would tip the story, but because they changed it, it worked out.

CASEY: I think that’s also a positive for us that we don’t have to lock the shows too quickly — that these things can happen. Sometimes it’s gone too far and it’s going to cost a lot of money, but by holding off the dubs on these shows, we can go back in and not cause too much trouble.

HULLFISH: One of the things that I’ve heard other people discuss is: How do you maintain a cohesive style when you have multiple editors? But the footage speaks to you, right? If it’s the same directors, and the same DPs, and the same writing style and the same actors performing the same characters, that plays a lot into how you’re cutting it and the style of the edit, correct?

CASEY: I think all three of us have subtly different styles. I think I could tell whether Steve had cut something or Jacque cut this scene, because we all do it slightly differently. And I think that the fact that they don’t make us change it — they don’t want us to be cookie-cutter.

HULLFISH: That’s interesting. Do you think there’s a tell? Like with a poker player?

TOBEREN: Steve has a tell! He post-laps and pre-laps everything.

COHEN: And Jacque has picked that up from me.

TOBEREN: He’s got the story moving forward continually. So I kind of stole that. So I use it a lot now, too. But not always.

And I like to let shots play to an uncomfortable level because I think the actors are really holding it. And I think I do that more than these two do.

HULLFISH: It’s so funny that you mention that tell about pre-lapping and post-lapping, because I watched an episode that I know Steve cut….

TOBEREN: And he does it, right?

HULLFISH: One of my questions was about pre-lapping and post-lapping. There’s a show aesthetic that I picked up of letting things play — holding on things. Episode 404 — Season 4, Episode 4 — and there’s a great early conversation between two detectives at Bosch’s house and it really does play — each shot is held a beautiful length of time. There’s not a lot of overlap, there’s not a lot of pre-lapping, the pace of the conversation is slow as you would think it would. You’re letting the scene and the actors’ performances tell you with the pace is.

Later on, all the detectives are in the pit area, having a conversation that is very rapid-fire and EVERYTHING is pre-lapped. Is that a way to pace-up a scene to make it seem faster?

COHEN: Yeah sure it’s a way to make it seem faster. Of course. And it’s a way to make the cuts be invisible. And it’s a way to make — particularly for an ensemble — it’s a way to bring everybody together and make it seem like they’re all sort of organically connected.

We don’t want to think: “He talks. He talks. He talks,” too obviously; particularly if it’s a group scene.

TOBEREN: Because people overlap naturally all the time, so oftentimes we all pull people up and overlap them on top of someone anyway — especially a really intense argument.

CASEY: Yeah. I have found with those types of scenes that when you have a bunch of people, the audience will lose track of where they all are, so the slight overlap is good to just pull you in that direction. Sometimes there’ll be a look from one of the actors — when he first hears that overlap he’ll throw a little look and then you know the geography of it.

We don’t shoot a lot of close-ups on our show, so you don’t you usually lose track of those things, but I find when you have a lot of close-ups that it helps to throw you too where that person is sitting or standing or whatever and it doesn’t become a Ping-Pong game….

TOBEREN: A slide show.

CASEY: Slide show, yeah.

TOBEREN: Steve, you’re right. This is a matter of the scene. Technique is appropriate to a particular scene in a particular rhythm and a particular emotional state of the actors.

The scene you were talking about is very somber, thoughtful, and I thought the performances were great from both of them. You want to feature the performances as much as possible. Other times you want to speed it up — exactly what you said and change the rhythm.

HULLFISH: So if you’ve got the pacing of the actual speaking cut as tight as you can get it — you’re trying to make it seem rapid-fire Boom-boom-boom-boom — pre-lapping and post-lapping the picture adds to that speed more than if you just cut when someone starts to speak.

COHEN: But it also depends on what you’re trying to do in terms of a particular cut. Sometimes you want a hard straight cut because that has the most energy and it’s an important moment that has to be featured. And other times you just want to weave everything together. But yeah it can make it seem more kinetic, sure.

TOBEREN: Yeah. It depends on the information in the scene, too. What are you trying to get across?

HULLFISH: The scene with all the pre-laps in it I definitely got the sense that it was supposed to be this rapid-fire discussion. Everybody’s throwing in their opinions.

CASEY: It’s not unlike our three close-ups here [as we were all on the screen in a FaceTime call.] You have to decide: What am I going to show? But it’s about the rhythm. For me, it’s all about the rhythm of the scenes, whether you do much pre-lapping or less of it.

COHEN: Have you ever noticed that when Zoom shows you the speaker’s face as the main image, instead of as a gallery, it’s always pre-lapped.

TOBEREN: I didn’t notice that.

COHEN: Because they hear the voice first — wherever the loudest sound is coming from — it analyzes that and then it makes a picture cut.

TOBEREN: Is it pre-lapped with the little box around the frame?

COHEN: Yeah, it’s pre-lapped that way too.

TOBEREN: Interesting.

HULLFISH: How has your approach to a blank timeline changed over the years? Have you found a way that you always do and you’ve stuck to it or have you evolved as you’ve cut?

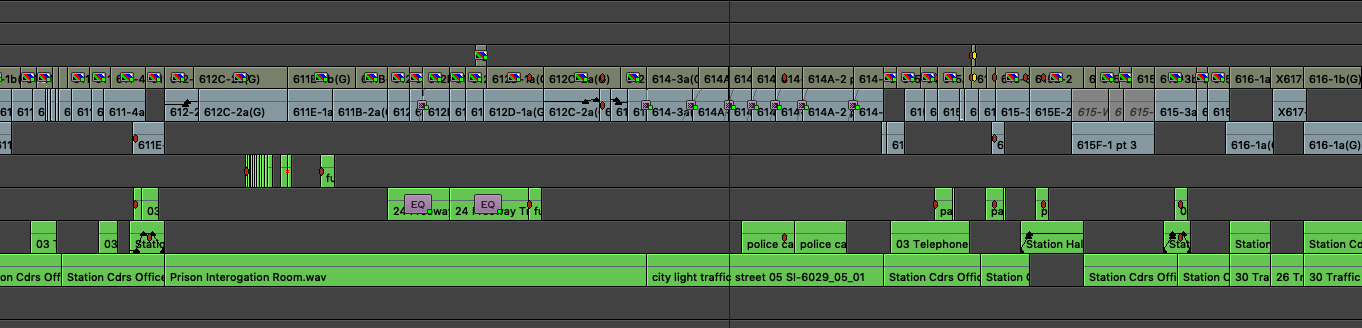

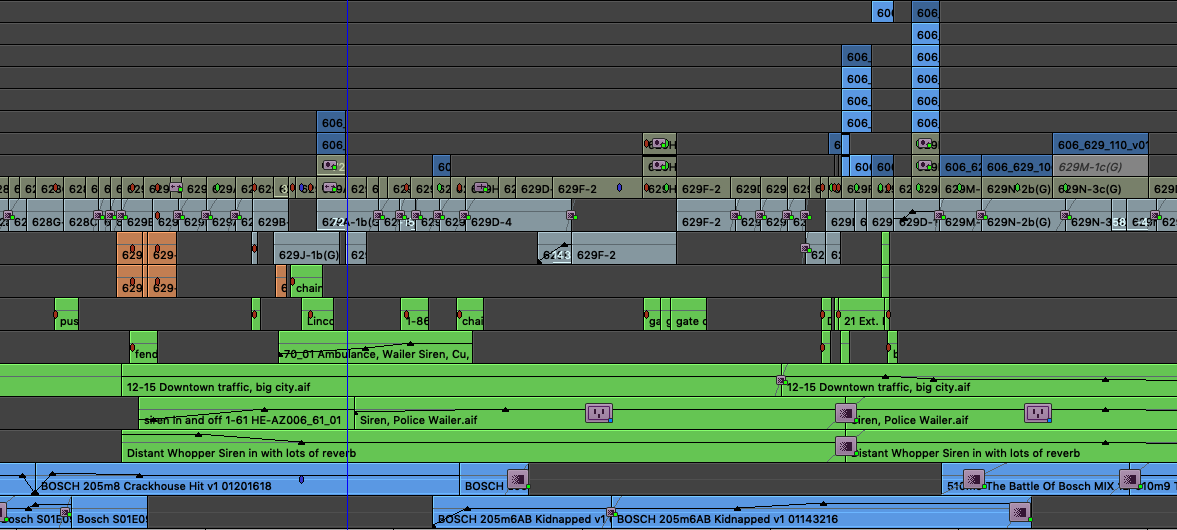

COHEN: Oh that’s a great question. Coming from film and then cutting digitally — on film I did a lot more finessing of individual cuts before I would move on. With digital editing, I go through a scene pretty quickly and throw a lot of stuff in the timeline.

I’m pretty sure I’m going to be in a certain place for a certain line and then that line goes in the timeline without finessing the cut at all. The cut will be terrible. I know it’s a terrible cut. And I go through the whole scene that way, so now I’ve got this completely roughed-out thing that has a structure and that has the best performances that I could find and the best sizes, but none of the cuts work and then I go back and refine the cuts.

That’s something that I only felt comfortable doing on digital because if you did that on film you’d have a million tiny little cuts that you’d have to fix and all these short trims it would drive you insane. But digitally that’s a great freedom.

My analogy is to surfing. I basically want to surf the film. I want to be cutting as fast as I can. Picking takes as fast as I can. Not to say that I would not look at all the material, because I do. And I make very careful decisions, but I want to get a structure as quickly as I can and then go back and once you have that structure you can refine things. You could never do that on film.

TOBEREN: I like to watch the dailies. I like to watch them all the way through and then I formulate it. Somehow I can see the cut in my head then. I can see the points that I really want to magnify. I can see what shots I want to be in for which part of the scene and I’ll put the scene together. Sometimes that formulation I have in my mind doesn’t work and I have to adjust it as I go.

I love to watch all the dailies and the outtakes too because sometimes you find outtakes that are actually better than the printed takes for a certain section because they print a take for an overall performance and you may find a line here and there that’s better in the outtake, but that’s what I normally do.

And then, if I have a huge action scene, I have to watch all the dailies several times to formulate what I’m going to do and then I structure it and then I go back and watch them again because you may have three bins of dailies on a big action scene.

HULLFISH: Do you watch those dailies in shot order — take one through take seven?

TOBEREN: Yeah, I do. The way my assistant sets them up, I just watch them the way that she has them set up. Sometimes I’ll skip around if there’s something that I know they did because I heard a rumor that they shot this great shot and I want to see it.

That’s generally what I do: watch everything first….

COHEN: I think we all watch everything first.

TOBEREN: I’ve known editors who don’t watch the dailies. They watch them as they’re cutting.

COHEN: I’ve known that too. TOBEREN: And I don’t do that. And then I actually get up and walk around for five minutes and think about it and come back and start cutting. HULLFISH: And when you’re watching those dailies are you watching them passively or are you actively making markers or…? TOBEREN: I take notes sometimes, but I have an amazing memory for some things now. Because I’ve been doing this for so many years and I can just click on the take and know exactly where I am. It’s a skill you just develop. I don’t know how you do it, but you just do.

HULLFISH: 10,000 hours.

CASEY: I kind of approach it more like Steve than Jacque, but I don’t have much experience in actual film editing — editing with actual film. I kind of came in a little bit later. I only worked on a couple of things as an assistant on film.

But I look at the dailies for a normal scene — I just watch them.

I don’t usually take notes unless I’ve got a whole bunch of takes. It’s not usually over-shot, so we don’t usually have too many takes. After I’ve watched it, sometimes I see it in my head — as Jacque says — I can see the whole thing and I know exactly what I want to do. Other times I don’t.

And so then I’ll just go to the beginning again and I’ll look at the first line or the first few lines of the scene in each take and I pick the one I like and I put it in and then I get to the next line of dialogue. Even if I’m not going to make a cut. Maybe I just take each line of dialogue and look at all the takes and find out where the best performance of that is.

And like Steve, I just pound it in, and then I go back and look at it and see where it doesn’t work. It might be the best take but I can’t cut to that shot there. And so then I will start to finesse it and then it just falls into place. So that’s kind of how I approach it.

TOBEREN: The truth is that the film tells you where to cut. That’s always how it is. Wherever it’s best in that area.

CASEY: As I’m watching the dailies and I see something that I really like — even if it’s at the end of the scene — I’ll edit that into the timeline first. That’s where I want to be. I sometimes actually cut the scenes NOT from beginning to end. I’ll see the point that I really want to make and that’s going to go in and then I say, “How do we get to that piece?” And I back it in. Not always. I just don’t really have a go-to way of doing it.

TOBEREN: Yeah, it’s different for every scene you do. And then you’re done at the end of the day and you think, how did I do that?

COHEN: I think that every day!

I know a lot of young editors listen to your podcast, Steve, and the one thing I would say is: we all watch the dailies obsessively in one way or another. I watch them at least twice. I watch them once before I start to cut and once as I cut — I sort of go through everything a second time. So it’s at least twice.

And I think that the process of watching dailies to a young editor might seem like a waste of time. Because you’re not actually doing anything. “I want to get to it, I want to cut. Why am I not cutting. I must be wasting time. This is taking too long.” And actually — and I think we’ve all said this in different ways — is that just the process of watching it is a process of creativity. Just seeing it, it’s going into your consciousness or unconscious and you’re absorbing something and you’re learning about the film and you’re making different choices and you’re memorizing it. All that stuff is really important even though it doesn’t look like work product. I think it’s a very common mistake for young editors that you start cutting too soon. You start cutting before you have a point of view on the scene, for example.

CASEY: I think a problem in today’s world in episodic television — not on Bosch — is the amount of dailies that people are getting these days. They’re getting 5, 6, 7 hours of dailies and you can’t watch seven hours dailies before you start cutting, or you’re never going to get anything cut.

The style of our show is not an overshot show. We don’t shoot tons of angles — depending on the scene — and you can watch the dailies. Like Steve, when I finish a scene, I go back and I look at the dailies one more time too, to see if I’ve missed something.

I know Jacque’s worked on a couple of shows the last few years where she’s getting enormous amounts of film. It’s a big problem because they’re not giving you any more time at the end of the week to show it to somebody, so I don’t know how they do it. I really don’t.

TOBEREN: Well a lot of these young editors that are starting out are taking work home with them and they’re going home to put their baby to bed and have dinner and then they start working again until 1:00 in the morning or whatever. It’s incredibly unfair.

They do it to get a start to get a reputation and get a name out there and luckily we don’t have to do that. They work on weekends for nothing.

COHEN: Unfortunately there’s just a mathematical calculus to this that says, “If I have seven hours of dailies and I want to watch it all how do I cut it?” You have to find a way to triage it. You have to find a way to reduce the watching time.

TOBEREN: I think a lot of editors — in that case — they go to the last take because there’s just no way they can get through all that material.

COHEN: That’s a common short-cut. Just use the last take and forget it.

CASEY: And if there’s a bunch of stuff for one line they’ll go back into it. If they have a problem. COHEN: Yeah, they can do that. I’ve known people that do that too. I know people who’ve laughed at me for watching everything. They’ll say, “Oh, I never watch everything.”

TOBEREN: A lot of shows are now shooting three cameras all day, every day. Now that’s going to give you at least six to seven hours and dailies a day. If not more. I worked on The Good Wife the first season and one day I got seven or eight hours of dailies and Scott Vickrey got ten. It was a courtroom day. That was my first experience with getting so much film.

CASEY: I got her calls three times a week at home.

COHEN: Kevin and Jacque have worked together for years so they’re kind of like old pals whereas I was I was on Bosch a little bit before they were.

HULLFISH: But you’re the new guy even though you’re the first guy on the show.

CASEY: Jacque and I go back. We worked on ER together for 12 and 13 years. She was one more year than me.

TOBEREN: I thought I worked there for 14 years.

CASEY: You did, but I mean together. I did 13. She did 14, out of 15. So we’ve been around a long time together and had been looking at each other’s film and have been screaming at each other and hating each other and loving each other.

Then I saw Steve Cohen and I said, “Isn’t that the guy that wrote the book?” I had known of Steve for many years, but it’s interesting because Jacque and I came on at the exact same time, which is a pretty funny story in its own way.

TOBEREN: Steve is definitely the Pooh-Bah. He definitely is. He’s our editing Pooh-Bah.

CASEY: On all levels of course.

HULLFISH: So I want to hear the funny story! What season was it, and why did you come onto the show at the same time?

CASEY: They did season one, which Steve was on and there were two other editors who worked on it. My ex-assistant — who I worked with for my whole career on ER. and then many shows after that — she had worked on season one and now she’s assisting Jacque now on Bosch.

Judy Guerrero is her name and she called me between the two seasons and she said, “Two of the editors aren’t coming back on Bosch.” She had been telling me how great it was to work on the show. She said it was just great people.

HULLFISH: And low shooting ratios!

CASEY: All that stuff! She said that they got to go home at 7:30!

TOBEREN: Even though first seasons are always hard.

CASEY: So I called my agent and I told him and he said, “OK, we’ll get right on it.” And then, of course, I called Jacque — because we’ve been friends for 20 years — and I said, “There are two openings on Bosch, but I don’t know anybody. My agent is working on it.”.

TOBEREN: But you said that Judy worked on it.

CASEY: I didn’t know how Jacque did this, but she just sends an email to Eric Overmyer — the head guy — personal email, and she’s got an interview the next day.

I call my agent I said, I just told a friend about this and she’s already in for an interview! I’m not going to get the job! So Jacque calls me that night. She’s hired on the spot.

I call my agent. I said, “Now there’s only one opening on the show!” Anyway, the agent got through and I went in the next day and they hired me on the spot, so that’s how the two of us wandered in there.

Then we had to deal with that third guy, which turned out to be pretty good. We went to lunch one day before it all started and it went great from there on.

TOBEREN: I wasn’t hired on the spot, by the way.

CASEY: Well pretty much. The same day.

TOBEREN: It was the same day, the end of the day.

HULLFISH: Don’t ruin a good story with the truth!

CASEY: That’s right! Thank you, Steve. Thank you.

It’s all very close. I walked into the interview and Eric Overmyer and Pieter Jan Brugge were the two people in the room and they both had grey hair and T-shirts and jeans. I thought, “I at least have a shot at this.”

HULLFISH: Steve, how did you come up with this job?

COHEN: I was contacted by Dorian Harris who I had worked with on another show. Dorian cut the pilot. It’s not a particularly fascinating story, just kind of a “who-you-know” story. And then I came in and like them I interviewed with Pieter Jan Brugge and Eric Overmyer who I instantly fell in love with, and I left the interview calling my agent saying, “I GOTTA do this show.”

TOBEREN: You didn’t really want to do a show at that point.

COHEN: I was exhausted. The Bridge really took it out of me and I wasn’t ready to go back. But after I met them, I very much was.

HULLFISH: You said that you got this by knowing somebody. That is not a negative thing to get a job because you know somebody. It means that you have performed in a way that those other people that know you, like you and want to work with you again.

TOBEREN: And they’re confident to recommend you to their contacts.

CASEY: Every show I worked on after ER ended — which was 2009 — until I got Bosch, was from somebody that I knew from ER.

Bosch was the first show that I didn’t know any of the executives or any of the writers on that show. It is important who you know.

COHEN: It’s part of what makes editing unique. It’s such an intimate and personal thing — what we do. It’s so instinctive and so hard to define and the relationships with the other principals — with the producers and the directors — is so close.

You’re sitting in a small room with somebody. You see their flaws. They see your flaws. So a lot of the job is: “Who am I willing to sit in a room with for an extended period of time? Can I tolerate them? Can I have fun with them? Do I respect the way they think?”

How many judgments do we make in the course of one scene, let alone a whole episode? You make thousands and thousands of choices all day long and you have to be able to trust somebody that their choices are gonna be good ones — even if you disagree with some of them. But you can’t remake a thousand choices. I’m speaking from the perspective of a director or a producer.

So it’s all about trust. And trust comes from interaction. And it comes from references but that doesn’t mean you don’t need to know things. We all got this job because we were respected, we had a long list of credits and somebody believed that we knew what we were doing. It’s always a combination of what you know and who you know.

CASEY: The way you work with the people in the room has a huge effect on all of this stuff. You have to know how to play the game to some degree. People come in and they give you notes and you’ve watched every frame of this footage and they tell you, they want this or that, and you go, in your head, “Well that’s never going to work.” But you have to know how to attempt it. You have to try it and you have to hope that the people that are on the other side are going to look at it and say, “You know, yours was better.”

You win some of those and you lose some of those, but I’ve seen editors who have gotten themselves in a lot of trouble by “putting their back up” when they get asked to do something. It’s all a collaborative effort. We’re all working on the same thing.

TOBEREN: You don’t own it. You do not own the material.

CASEY: You just have to hope in the end that it’s going to come out the way you can live with it. And it usually does, if you know how to do it right.

I’ve sometimes even put stuff in that I didn’t really want — not on Bosch — but once in a while on ER, because we’d have these trauma scenes and they could be cut a million ways. I would make sure that if I wanted to see the dagger or the guts or whatever twice I’d put it in there three times, knowing that they were going to say, “It’s too much!”.

TOBEREN: The other thing that you have to be is a translator because you can work with some directors who may be brilliant at directing, but they’re not good at telling you what they want out of a scene in the cutting room. They’re not good at communicating. So you have to learn how to read between the lines and figure out what is the kernel of what it is that they’re trying to tell me.

COHEN: Yeah. You have to be a good mind reader. Because some directors know what they want but can’t articulate it or can’t operationalize it — to say, “I know what I want out of the scene, but I can’t really tell you how to do it, and I can’t admit that I can’t tell you how to do it.” So I’ll tell you what to do, but I won’t be the right thing. And it’s a process of mind-reading to say, “OK. I think I know what you really want” and give them that.

So a lot of that relationship in the room — we all know this — is a big reason you get hired because you can navigate those relationships and help everybody to feel comfortable and everybody get what they want.

TOBEREN: Yeah. You want everyone leaving your room happy.

HULLFISH: That’s why I’ve got chocolate on my desk. (LAUGHTER).

COHEN: Somebody clued me in on that years and years ago and had all this food in her cutting room. We actually had a conversation about it and that was why she did it. That would never occur to me. But I learned from that and my cutting rooms changed after that.

HULLFISH: How you treat people and how people want to be with you in an editing room is crucial. No matter how good of an editor you are what they’re gonna remember is how they FELT when they were working with you.

TOBEREN: You’re absolutely right. That’s why I say, “Make sure they leave your room happy.”

CASEY: One of the great things that I find on Bosch is that our producers don’t want to sit in the editing room all day. They come in and they have their ideas and they give them to you and they trust us. They leave. They don’t have to sit there, and they know when they come back — the next day or whenever it is — it’s going to be what they want. That’s the part Steve was talking about: trust. They learn that they can trust you because you’ve treated them properly along the way.

Other times you get these people that have to sit there and watch every three frame trim. That’s when I get a little crazed.

TOBEREN: That’s the beauty of Eric Overmyer. He has done so many wonderful projects and he knows the whole process so beautifully. He knows exactly how something’s going to turn out even if YOU get off track, he can bring you back on track in two seconds by saying three words. It’s amazing.

That’s the beauty of working on a project like Bosch with producers and creators that have been doing this for 35, 40 years.

COHEN: We are very blessed to have some extremely smart and creative producers and writers on the show. We have a really great talented writing team and producing team.

TOBEREN: Yes we do.

COHEN: They’re really good at what they do. The actors are good, too. The actors are amazing. Titus Welliver is incredible. Madison Lintz is amazing, too. They’re all great.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about the notes process. Having the right attitude towards them and being able to read the tea leaves about what the notes really mean.

COHEN: It’s a great question, too, Steve. That’s an editor question.

TOBEREN: Yeah. So the very first thing is you cannot take it personally. Like I said earlier — you don’t own it. You do the work on it and you can be proud of your choices and the way you’re trying to tell the story, but in the end, it’s not yours. It’s the showrunner’s point of view and you can’t take it personally if you missed that interpretation for that particular scene or whenever.

I remember I had a scene that I did, and I had gone into close-ups too soon. But it was my very first season on Bosch and we rarely use close-ups on this show, and I felt horrible that I had done that because there were some very strange angles in this scene and I wasn’t getting a lot of feedback from the director. But ultimately I got to the place where it was a much better interpretation of the scene by staying wider.

Eric just came in and said one or two words to me and that just completely changed my whole perspective on that scene. He said, “This is way more of a group endeavor than focusing and individualizing someone too much.” Just by saying those few words. It changed my whole take on the way that I cut the scene and he was so much happier. But I felt awful that I had disappointed him.

CASEY: When you first start on a show, those are the kind of things that can happen. You’ve coming out of whatever you’ve come out of — a different type of television show. But I think after a couple of episodes we got into the style and we knew what they really wanted.

What happens on Bosch is that Eric comes in and looks at it first — after the director works their four days or whatever they need. And then we run it just for Eric. Nobody else sees it yet. And he only tells you to stop when he wants you to.

My assistant will be in there, and she’ll take the notes. It’s always about the story. Very rarely is it about how we’ve cut something — once we got into the feeling of how the show kind of goes together. And then he’s gone in an hour and then he just lets you do it, and it’s very comfortable.

After he’s finished with it — which is one or two little passes, really — then we send it to all the producers and writers. Then the note process becomes a little different, although most of it funnels through Eric. It’s very comfortable. Obviously, we’ve been on shows that have been anything but comfortable.

TOBEREN: Where every producer gets their own cut!

CASEY: And then you get notes from two different executive producers that are completely opposite.

COHEN: Warring notes.

CASEY: They’ll say, “Oh, I’ll talk to him about it,” and then they never do. So then the other guy comes back and says, “Why did you do that?” “He told me to do it. He said he told you.”

That doesn’t happen on Bosch, which is nice.

COHEN: This is just the nature of the job for editors. We all have egos. By definition, you have pride in your work. You have to. That’s why you do it.

Sure, when you show the work to somebody else they’re gonna want to change it. You have to make your peace with that.

I think part of it for me is also understanding that — if you think in terms of a director — because we work with the directors first, it’s hard for them in a different way.

You’re basically running a cut for a director and they’re critiquing themselves when they’re watching it and they’re worried that their work was inadequate in some way, and you think that it’s all about YOU, and it’s not. You’re both kind of scared and thinking, “Who’s going to tell me that I screwed up here?”

Having some equanimity about that and just not getting too possessive about changes and too resistant. I think that’s a challenge for all of us in one way or another. I don’t think any editor fully escapes that challenge unless you’re just so passive that you have no point of view.

And from the perspective of the people you work with, they want you to have a point of view. How could you do the work if you didn’t have a point of view? So you want to have a point of view but you want to know when to stop beating a dead horse on that point of view and back away. And that’s something you just learn over time.

Everything has to do with your personality. You can’t really get rid of your personality. You can’t transform your personality. You come into this with who you are, with what your instincts are, what your emotions are, what your way of relating to people is, with how you approach the material. And for better or worse it’s who you are.

HULLFISH: I love that idea. When you’re getting those notes you have to realize that it’s not about you. They’re seeing their own work. Like, if you’re working with a director, he’s not seeing bad edits, he’s seeing direction or the story in a way that he doesn’t want to see it. I don’t think they are thinking, “Oh my gosh! This person doesn’t know what to edit.” They’re just trying to get their point across.

CASEY: Sometimes they do. (LAUGHTER).

TOBEREN: They’re seeing the shot that they caved in on and they didn’t shoot and they’re really missing that shot in the cut and they’re wishing they’d gotten that shot, because by the time they walk to their car at night, put their hand on the handle to open the door, they’re hitting themselves in the head saying, “Oh! Why did I do that?”

COHEN: Everybody sees their own work. What we are focused on when we’re really close to it is not the same thing as if you go back and look at a show years later. When you go back to it, you have that perspective. It’s the story that you’re watching and the characters, and if they work, the show works.

TOBEREN: And how it makes you feel. How you feel as you’re watching it and If you want to keep watching.

CASEY: I was watching Bosch last night actually the episode Steve mentioned earlier, 404, and I thought, “I wonder why he did that?” (laughs) I realized that I was just taking it in and it was all working. I wasn’t looking at the editing. Everything is in the right place.

I was told way back by an editor I worked for when I was an assistant: If you keep this in mind it’ll work for you. “Always cut to what the audience wants to see just before they know they want to see it.” And I try to keep that in the back of my head.

HULLFISH: What are some of the things you three do to help your assistant’s move forward and get their spot in the editor’s chair?

COHEN: Well, first of all, we want to engage the assistants and bring them into the process as much as possible. And what we’re looking for — what I’m looking for — in an assistant is somebody that I can do that with and feel comfortable with and feel that they can make a contribution to the picture. That we’re all working on the movie together.

I’ve had assistants that were just technical — and while that’s great and it’s helpful to have somebody who’s really good technically — I really want somebody who I can reflect ideas on. We all need to be working on the same movie together, not just technically throwing files around.

HULLFISH: Who is your assistant Steve and what’s something that they do for you that you appreciate or that makes them special to you?

COHEN: My assistant is Rafi Nur and I think he’s terrific. He’s very technical, which is fine and I really value that, but more than that he really understands story and he offers me meaningful contributions in terms of story structure and content. That’s very valuable and very rare frankly.

HULLFISH: Jacque, what about you? Who’s your assistant and what do they do for you? How did you find them? What made you think that they would be a great assistant for you?

TOBEREN: My assistant is Judy Guerrero. She’s great. Since I started cutting many years ago, I’m not that technical, and Judy is, so she does everything technical. She has a great story point of view. She’s always present and involved with everything with the executive producers. She’s incredible. I mean she’s been doing this for a very long time and she’s savvy and well-developed on all levels.

HULLFISH: Kevin, what about you? Who’s your assistant and tell me a little about her or him.

CASEY: My assistant is Knar Kitabjian. Like all of our assistants, she’s just fantastic. I rely on her very heavily for everything. I like to keep her up on everything. She’s involved. She’s very technically savvy, which is good because I’m not overly technically savvy and she can keep me on the right path and all that technical stuff.

She loves to be in the room and I love to have her in the room whenever she can come in. She’s always in with the producers or director. She takes my notes. I don’t really take notes unless it’s a really specific thing that I think of in my head that I want to make sure I don’t forget.

Then she likes to sit with me when I do the notes. I say, “what’s the next note?” although I can usually remember what we just went through, of course. But she’s fantastic. She helps me a lot with the sound effects that we have to put in and the music.

HULLFISH: Do I recognize her name from elsewhere in the credits? Knar?

CASEY: Last season she was offered to edit episode one.

HULLFISH: Wow!

CASEY: They chose to offer her an episode and I think that’s great.

COHEN: Steve, you’re asking how do assistants make that transition, and part of it is finding ways to get the assistants to do creative work and get that to be visible to the producers. That means editing scenes, cutting music, cutting sound effects. And for us, also cutting the recaps — every season starts with a recap.

HULLFISH: I think that first cut is so small a part of the process when you’re first assembling a scene, and that the real … I see Steve shaking his head in disagreement. I love that. The REST of the process is so important: understanding the notes and understanding how a scene develops from that first cut is critical to a young editor — an assistant editor — moving up, I would think.

CASEY: Well I kind of disagree. When I finish my first cut, at that moment that scene is done. That scene can go on the air. I don’t rough-cut anything. I want as few notes as possible and we don’t get a lot of notes but I think if you really work hard on your cut and you polish it, that should be the cut.

TOBEREN: I feel the same way — that the cuts should be the cut. It should be very representative of the best performances, the best of everything.

CASEY: With the equipment we have now, what we can do, we can polish it with sound and music and everything and I want it to be something that I would show to anybody at that point.

COHEN: The reason I was reacting the way you noticed, Steve, is of course the notes process is transformative and it has to be. We all have to find our way to be open with that and we also have to feel that we’ve done the best job we can to start with.

But looking at it from the perspective of the producer or director, no matter how many notes you get there’s a lot of stuff that can’t change. As I said, you’ve made 10,000 choices unconsciously in one scene and it’s very hard to uncut every cut and change every cut. And it’s rare that that happens because it’s too much work.

CASEY: They don’t want that.

COHEN: Nobody could possibly want that. They want to know that in broad strokes you’ve done something that they like. And then the notes are basic to something that’s accomplishable in a reasonable amount of time.

If you have to start over and remake every cut, everybody’s gonna hate that.

HULLFISH: Did you guys have to hit time?

CASEY: We had a pretty big window. We’ve had shows that have been like 41 minutes and we’ve had shows at 59 minutes.

COHEN: We worry about length within a range. We don’t have to shorten every shot to take a minute out of an episode. We never have to do that. And that’s great. We can let the material play as it needs to.

HULLFISH: Does it change your first edit to know that you have that much flexibility? The reason why I ask that is that I noticed that there were several scenes where you see people pulling into a driveway and sitting in their car that on some other show, you may think, “Hey, that’s shoe leather.” But you also realize how important it is to the scene that the person’s kind of preparing themselves for what they’re about to encounter when they get out of the car.

CASEY: It’s never about a time situation. That’s what the scene requires or it doesn’t. We’ve cut into some of that stuff.

TOBEREN: We do a lot of jump cuts in the show.

CASEY: But sometimes that has to it has to be. You have to show the whole thing.

TOBEREN: It’s a character moment.

CASEY: And other times we just jump it, but we don’t do it for time.

HULLFISH: But on some shows, you might, right? If time is critical in a broadcast show, and the only way I do it is if the guy pulls up and gets out of his car…

CASEY: Then it becomes the shoe leather that you’re talking about. Usually, it becomes obvious.

HULLFISH: When you decide to do a jump cut — since you brought up jump Jacque — do you feel like that has to be something you’ve prepped an audience for early in the season or early in a show? I saw jump cuts as Bosch pulled stuff out of evidence bags.

CASEY: We do that all the time with stuff. With props and pieces of things. But we’ve also just jumped right through oners.

COHEN: I think audiences are prepped for that kind of stuff, now.

TOBEREN: If you do it right, you don’t even see them, if they’re done right.

CASEY: I think our show is actually much more opened-up than most shows. We let things breathe much more I think than network television ever does.

TOBEREN: Network TV, you can have 10 cuts for 4 words of dialogue.

HULLFISH: So as an instructive question about the jump-cutting in the scene that I was talking about if there are no time constraints what is the editing purpose? What is the story purpose of doing the jump cuts if you could have him looking through these evidence bags for 10 minutes, why jump cut it so it all happens in 30 seconds?

COHEN: The point was how interesting is it for him to go through item after item after item? It’s all wasting time getting to the important stuff. That was a question of how do you sort of build a sense of tension without belaboring it.

CASEY: And frankly, I think it requires much more work to make those things look right.

COHEN: Yes. That’s right. It’s actually harder to do that.

CASEY: It’s very hard to cut that stuff.

TOBEREN: It’s giving it a style.

CASEY: It’s jump cuts, but every cut has a reason.

HULLFISH: It’s the classic Mark Twain quote where he says, “I would have written you a shorter letter but I didn’t have the time,” right?

COHEN: That’s exactly right! Couldn’t be said better.

TOBEREN: Could not be said better.

HULLFISH: Well on that lovely compliment to me I will end this interview.

COHEN: Thank you, Steve.

TOBEREN: Thank you, Steve.

CASEY: Thank you very much. It was fun.

HULLFISH: It was great talking to all of you and getting such fantastic wisdom from some really experienced, fantastic cutters. Thank you.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed, and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now