Editor Simon Smith has worked on a variety of TV series in the UK for the BBC, including National Treasure, Electric Dreams, Victoria and Endeavour, among others. His latest assignment was the popular and buzz-worthy Chernobyl on HBO.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

This interview will also soon be available as a podcast.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s9APLXM9Ei8

HULLFISH: My son and I have been addicted to Chernobyl, we really love it, It’s great work. Congratulations! I understand you edited some of the episodes, could you explain what your role was on the show?

SMITH: Thank you so much. There were two editors — a fantastic editor named Jinx Godfrey and me, and we basically had alternating episodes. She had Episode 1, I had Episode 2, she had Episode 3, I had Episode 4 and then we were set up to co-edit Episode 5. We kind of split Episode 5 as the scenes came in, and then later we split it by parts of the film, and then eventually Jinx finished on the project and I just did the notes that came in from the director and the execs. Episodes 2 and 4 were really just mine.

HULLFISH: This looks like a series that would have been cross-boarded. (To shoot scenes mixed across multiple episodes instead of only receiving scenes one complete episode at a time.)

SMITH: All five episodes were shot during a single 100-day shoot, out in Lithuania and all over Eastern Europe. So sometimes a day would come in and it would just be scenes from Episode 2, or sometimes they would come in and it’d be scenes from Episode 1. We had the schedule so we knew what we were getting and there would be periods of time when I wouldn’t have any scenes coming in, so I could sit and really work on what had come in before that. It was quite a luxury really to have two editors working on separate episodes during the same unit shoot.

HULLFISH: So you were both working on shared storage at a location separate from where they were shooting?

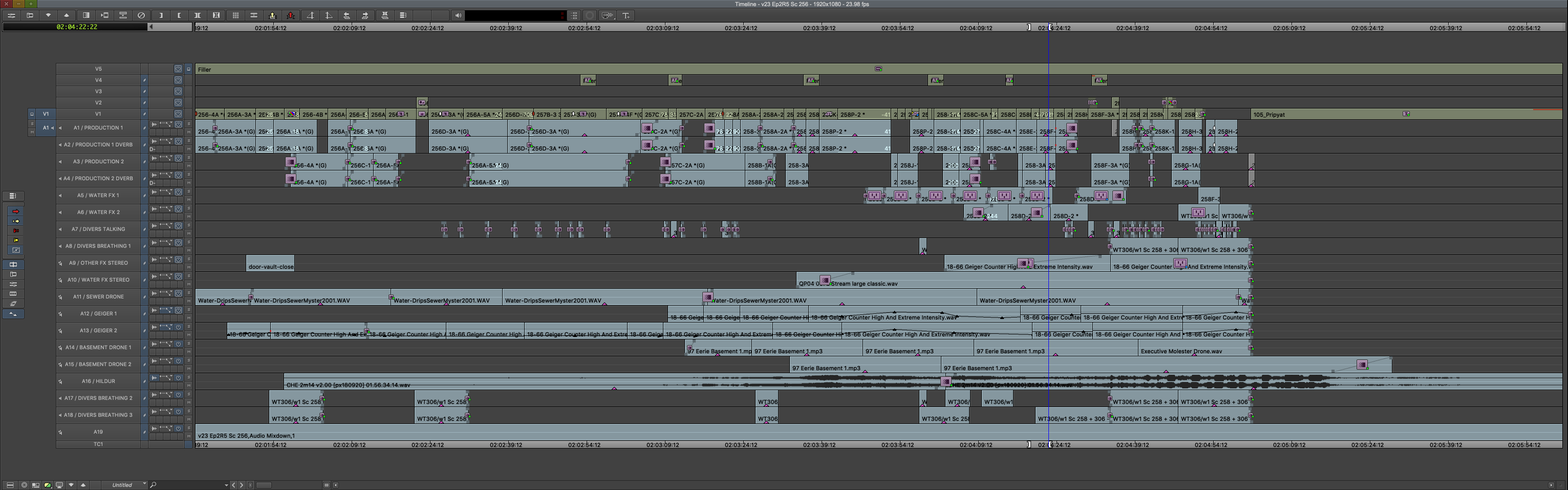

SMITH: Yeah, we were in Soho in London in a facility called HireWorks, which is popular with big shows and big films. We had Jinx’s Avid, my Avid, three assistants on Avids, one VFX editor on an Avid, and all connected to the ISIS. And we were all in the same project as well, so I could open any of Jinx’s bins, she could open any of my bins. It was huge. It was about 10 terabytes of DNxHD36 media for the five episodes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z_ThApl8GcU

HULLFISH: I love the opening in Episode 2, which starts out with a little montage of Russian mosaic artwork over a bed of a Russian language voice and no translation of what it means. Tell me a little bit about that choice and how it was made.

SMITH: I love that too. That was scripted, but I think the original idea was to have it in English. The first version I did had it in English, but it had come to the attention of Craig Mazin the writer as an old poem, and so I found that on YouTube, read in Russian on a radio station, and I laid it in in Russian and instantly loved that. There are certain parts in our series, like the evacuation announcement later in Episode 2, or in Episode 1, when they first phone emergency services, that’s the real phone call. I guess it’s just about creating a world. It puts you very much in that world, by having that poem — especially at the front of the episode – it puts you in the world of these characters and situates them in that place and that time.

HULLFISH: Another sequence that I loved was that sequence where that physicist — Emily Watson’s character, Ulana Khomyuk — wipes down a window and then runs it to the lab and it’s a really nicely paced sequence of her walking to the lab, doing the test. Tell me a little bit about the decision of “how much are we going to show?”

SMITH: Those are lovely rushes when they come in because you know — as an editor that’s where you can play with it. It’s all bits of sound design, clicking of switches and machines that are whirring and you get to put in some of that energy and then also moments of realization and fear when she looks at it and takes it in. I got those rushes in quite early in the shoot and it was a fun one to just jump-cut through: find every beat that progresses along her story. I didn’t have to show it in real-time. Just found the bits that were needed to tell the audience enough about what she was doing, that she was this high-enough level of scientist to really examine this stuff that was on their window with this machine and be able to draw a conclusion from that.

HULLFISH: Another moment that I really love the pacing is in the chaos of the hospital scene where you’re seeing people trying to be treated in hospitals where the cuts are quite quick, then contrasted immediately with the shot of Professor Legasov waiting to brief Gorbachev. And that change is dramatic. Tell me about the need to have the pacing be dynamic: faster in one spot, slow in another.

SMITH: We’re trying to show how this event is being spread out into the world and in this one area there are all these people going to the hospital and it’s very frantic. And then — somewhere else entirely — is this guy just reading about it on a bit of paper. It shows how big the event is, you know the event is big enough that it can affect those two different people in two different places in two very different ways.

You mentioned the hospital scenes – in that sequence of scenes there was a nice edit change late on in reviews, and that was just to change the order of a couple of those scenes. We had four or five different scenes in there. I work — as a lot of the editors that you speak to do — with scene cards up on the wall, so I could see the four or five scenes that were taking place in that frantic little set, and one thing I realized through looking at the scene cards was that I could place the scene of Vasily the firefighter and the scene of Lyudmilla next to each other, so we could create a relationship between those two characters. He’s sitting there burned and radiated and she’s trying to get into him. It was nice to look for ways of getting more out of those frantic cuts and beats. I’m a big fan of Eisenstein’s theory of montage — this idea of juxtaposing images to give meaning. Not just a chronology or not just a set of events that are happening side-by-side but to try and convey more meaning from them. Obviously, him being side-by-side with her did that for me.

Then to take it further — as you mentioned — the sudden change to this scientist as he’s sat quiet in a waiting room. It’s a way of giving the audience a ride — taking them somewhere and just when they are in one flow you take them somewhere else. That keeps an audience engaged.

Then to take it further — as you mentioned — the sudden change to this scientist as he’s sat quiet in a waiting room. It’s a way of giving the audience a ride — taking them somewhere and just when they are in one flow you take them somewhere else. That keeps an audience engaged.

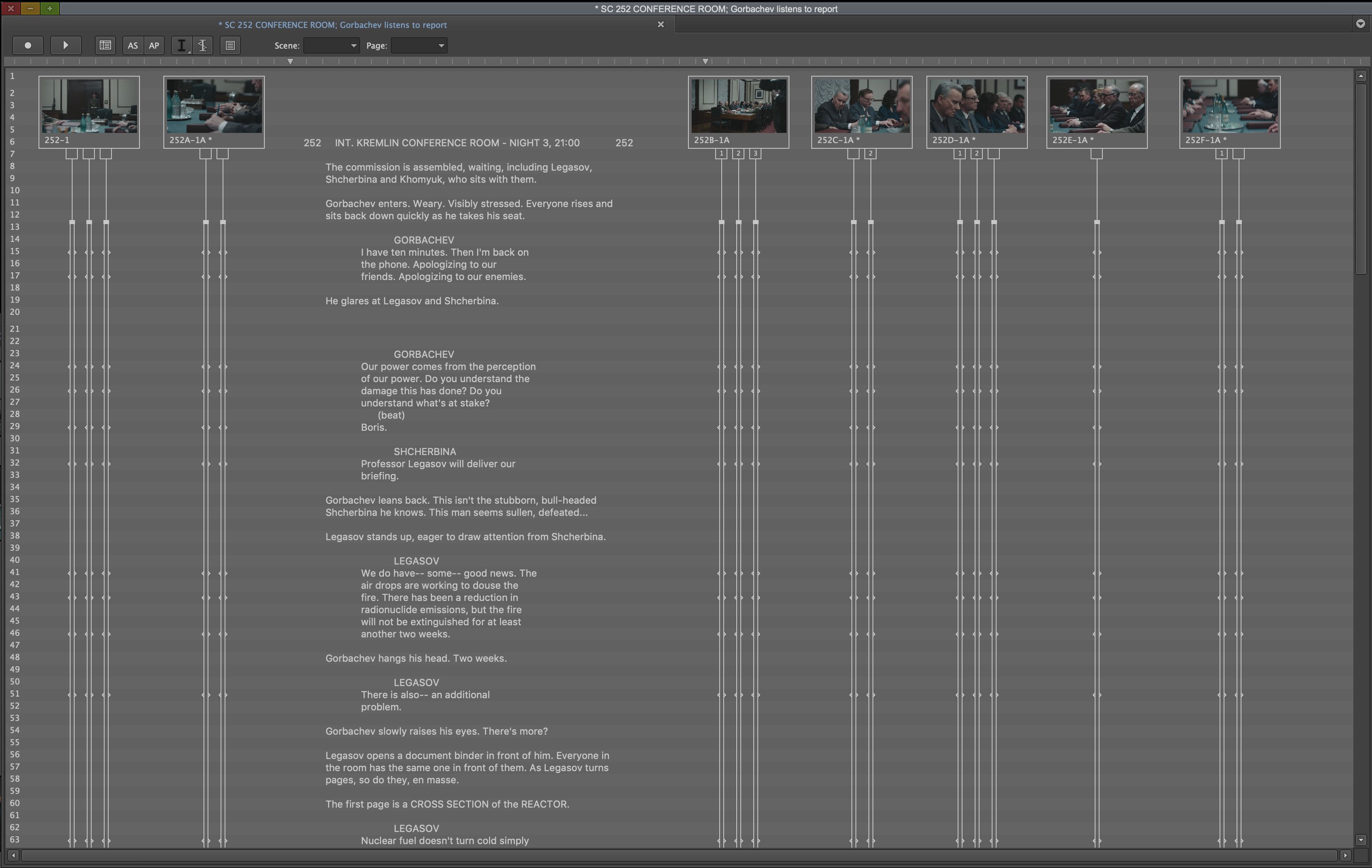

HULLFISH: Coming out of that waiting room, someone could consider the long walk that Legasov takes into the conference room — once he realizes the horror of what he’s just read — to be what editors derogatorily call “shoe-leather.” But if the walk serves a story purpose, then it’s not really “shoe-leather” right? You watch him walk from where he’s seated into this important meeting. Obviously, you could have just cut and the door opens. Watching him walk into that room is almost like a horror movie.

SMITH: The way that I was taught editing — when I was an assistant, the editors I would work for — when they’d break down how they cut scenes and why they cut scenes, was this idea of point-of-view — trying to situate a part of the story from a particular point-of-view. Very much that whole scene — when he goes in, not just when he’s outside, but when he’s inside as well — is really skewed to his point of view — his experience of what’s going on, and I guess that’s why we go on that walk with him. It’s not just showing the scene. It’s not the function of “This is what happened in the Kremlin with Gorbachev.” it’s experiencing it through him. I think it works really well in that you feel his discomfort and unease and fear in that room. And also you see that he has got no idea how to act in that room. So going in there with him was about point-of-view, it was about feeling what he was feeling.

HULLFISH: To reinforce your idea of who’s point-of-view the scene is in, as the generals start to describe the situation and cover-up the fact that there’s a big problem, you’re not watching the General or anyone else in the room. You’re watching Legasov listen to, and react to the lies.

SMITH: I would have done cuts of that scene both ways. I often do a version at the start where I just piece together the actions. Then a version from a character’s point-of-view. Just see it from Legasov’s point-of-view, just try and be with him, where every shot decision is based on either what he’s seeing and what he’s experiencing or cut round to him for his reaction of what he’s seen and what he’s experienced.

SMITH: I would have done cuts of that scene both ways. I often do a version at the start where I just piece together the actions. Then a version from a character’s point-of-view. Just see it from Legasov’s point-of-view, just try and be with him, where every shot decision is based on either what he’s seeing and what he’s experiencing or cut round to him for his reaction of what he’s seen and what he’s experienced.

HULLFISH: Another place that I thought was really interesting is when they were driving the dosimeter to the plant for the first time — they wrap the truck in lead and the guy drives that up to the plant. The editing is all about building anticipation for what is going to come back with that dosimeter. It’s almost cut like a horror film.

SMITH: We have a cut in the middle of that scene where we cut back to Legasov again. The camera is straight on him and he’s waiting to find out. It’s tense and we made the decision not to end the scene with the truck and the dosimeter. We did shoot the truck parking all the way by the power plant, but then realized that we preferred to stay with our characters who are waiting, it’s from their point-of-view and that’s the horror. It’s the fear that they have. My whole approach to editing these episodes was about telling people’s stories, their experience. That’s what we were all trying to do, was tell the human stories. We weren’t trying to tell a disaster movie. We were trying to show how it affected the individuals who were there.

HULLFISH: Yeah, I thought there was great tension in that scene through the editing and choices of cutting to people waiting and pacing or just sitting there with their head in their hands.

One of the things that I’m really interested in is transitions between scenes and there’s a really nice pre-lap of the sound of the American news report over the shots of the smoke blowing past.

SMITH: The director Johan Renck would always say to join a scene that is already happening and to leave a scene before it’s over. Like that news report, you go into that room with Gorbachev and he’s already sitting there watching it. With the evacuation, you would often see things as they’re already happening. Even with the Kremlin conversation, you’re kind of jumping into these rooms where people are in conversation and dealing with the problem. So when it came to transitions, we wouldn’t necessarily start on an establisher or wide and then go in. We would start on a piece of detail or an action or middle of dialogue and then a few shots later you might cut to a wide and show the room. In Episode 5 — there’s a scene where at the end of a conversation, in my assembly, I had cut out wide and ended it with a beat on a wide quiet moment — but in the final cut, we just cut straight out of the conversation and into the car where they’re driving to the court. That was really driven by the director’s preference for that kind of immediacy and that particular rhythm.

SMITH: The director Johan Renck would always say to join a scene that is already happening and to leave a scene before it’s over. Like that news report, you go into that room with Gorbachev and he’s already sitting there watching it. With the evacuation, you would often see things as they’re already happening. Even with the Kremlin conversation, you’re kind of jumping into these rooms where people are in conversation and dealing with the problem. So when it came to transitions, we wouldn’t necessarily start on an establisher or wide and then go in. We would start on a piece of detail or an action or middle of dialogue and then a few shots later you might cut to a wide and show the room. In Episode 5 — there’s a scene where at the end of a conversation, in my assembly, I had cut out wide and ended it with a beat on a wide quiet moment — but in the final cut, we just cut straight out of the conversation and into the car where they’re driving to the court. That was really driven by the director’s preference for that kind of immediacy and that particular rhythm.

HULLFISH: There’s a cut like that in the first Gorbachev meeting when he tells General Shcherbina to take Legasov to Chernobyl. It cuts away and they’re boarding a helicopter.

SMITH: Yeah exactly. It cuts when they’re boarding the helicopter and it also cuts out of the room leaving them still sitting there. We don’t see them leave the room.

HULLFISH: There’s another edit that is kind of the opposite of that one. Legasov is told to go do something and when he goes — instead of seeing him leave the room — he stubs out a cigarette in an ashtray on the floor and the edit keeps us on the ashtray on the floor.

SMITH: Yeah, I loved that whole sequence at the beginning of Episode 4. It was about six or seven minutes before a piece of dialogue from one of our main characters. That was another thing that I felt was quite unique to this show and was a joy to cut, was that we had these long sequences of montage — these long sequences without dialogue. The evacuation is five or six minutes of just constant shot after shot after shot. And that’s from the script. I think that scene was about five pages of script, describing the evacuation in detail. Without cutting to dialogue from a person. That’s rare, I feel, from the drama scripts I generally get. You don’t get a five page montage scene.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PdhksxPy9f0

HULLFISH: So that leads to a question I had about another extended action scene without any dialogue, where the divers go into the basement water. When they go into that building the tension is fantastic. Was that actually scripted with the action spelled out in detail until their flashlights go out?

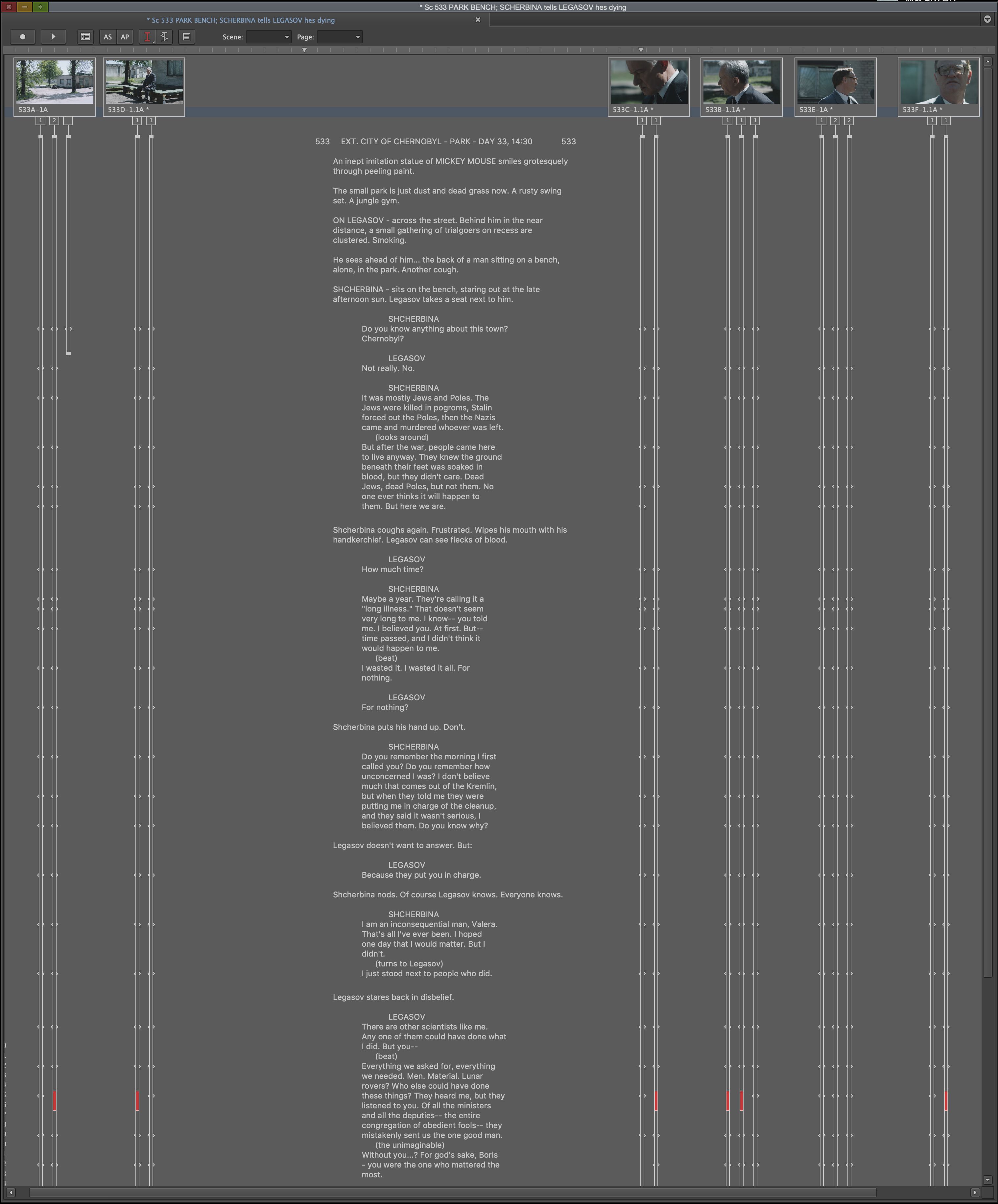

SMITH: I’m almost certain it would have been five pages of non-dialogue script. There was nothing about this that wasn’t scripted. Craig Mazin is at the top of the game and he’d been planning this for so long and he knew exactly how this film would be — more than anything I’ve worked on before — this stayed very true to the script as it was written, with scenes in the order that they were scripted, and very few changes, very few deletions of scenes. He’s made the scripts available online as well, so you can read the script and see that what he wrote — in that order — is pretty much what we get.

HULLFISH: I saw that those scripts were available (https://johnaugust.com/library). I just wasn’t sure if they were the shooting scripts or some other version.

SMITH: I looked at them and scenes that we omitted in editing have been omitted on the available scripts, but everything else is as he wrote it. So I’m looking at the script for the diver scene— that’s scene 255. One, two, three, four — four pages of detailed descriptions of how they walked around that maze of pipes and did what they did.

HULLFISH: How did you pace that, since some of the easiest ways to pace something is to kind of follow the dialogue?

SMITH: My first cut was about six or seven minutes and the final cut is about three and a half minutes, but I kind of just followed the geography of what they did. It was an amazing set that they built and bear in mind that they tanked that set so that the water can always be up at waist height.

I just followed them as they went around and tried to give their point of view of what they’re experiencing. When I could, I’d cut to their point of view as they’re seeing it, and not really use generic travelling shots. It was either experienced with them or through them.

One thing that Craig Mazin had said on his podcast — I remember even before I started the job — I’m probably paraphrasing but: Feature films tell the story in act one, act two, act three and kind of wrap it up nicely and that’s what you go for. But television is experiential. It’s not about necessarily a start, a middle, and a conclusion. It’s about experiencing something. TV is at its best when it’s experiential, and this was one of those scenes where my goal was to just make you feel like you were experiencing it.

And I really wanted the audience to experience the echoes. Technically there’s so much being done with sound in that scene that I broke it off that worked on it separately. I must have had 20 or so audio tracks in the end. It’s very technical and geeky – I used the D-Verb effect as a RealTime AudioSuite (RTAS) effect on some tracks, so I would have several layers that would have different kinds of echoes that would be applied to the whole scene. When there was a drip with an echo, that echo would just go on and on and on and until it naturally dissipated rather than end at the end of the drip clip. So that scene had to be approached in a different way technically, to achieve what I was trying to with ‘experiencing’ it.

I love that scene. I loved cutting it. I loved watching it. Everyone involved did such great work on it. The sound recordist, he had so many mics; he had mics inside the helmets on each of them so you could get each of their individual breath tracks and there were booms outside. We had options in abundance really. I’ve seen that episode in quite a few cinema screenings and every time I still feel my heart is pounding at the end of it, and I’ve seen it a thousand times in the cutting room.

HULLFISH: The other thing — for anyone that watches that scene — and please correct me if I’m wrong, is that is the kind of a scene that you would assume would have underscore to make it scary and to give it drama when there’s no music there. It relies on the sound of the dosimeters, right?

SMITH: Hilda Guðnadóttir, our composer, she really approached all of the score as a kind of hybrid of sound design and score. So there is a Hilda cue in there, but you’re right, it’s not a big, scary cue or the normal trope cliché cue you would have.

SMITH: Hilda Guðnadóttir, our composer, she really approached all of the score as a kind of hybrid of sound design and score. So there is a Hilda cue in there, but you’re right, it’s not a big, scary cue or the normal trope cliché cue you would have.

With the dosimeters, we had fun with those, and even more so in Episode 4. We really wanted to have complete control over them, so I was trying to find a way of attacking that. One of the first thoughts I had was to create an instrument in GarageBand, which was just the clicking of a dosimeter. Then, in GarageBand on your iPhone or your iPad, you can start a looping instrument and ride the tempo up and down, so you can actually make it click faster or click slower as desired. So I would start playing the scene in the Avid, and start my clicking loop, and then I would ride it up and down live and record it as I went. I did that a lot, but it was rubbish. It wasn’t working, and the reason it wasn’t working is because I’d make a mistake or it was very hard to revise it or manipulate it or change it afterwards. So I needed another approach. Then we found that in ProTools or Logic you can keyframe tempo just like you can keyframe volume in Avid. With that, you could find points in the scene where you wanted it to be going nuts and you could find points where you wanted it slower, and you would just keyframe those on the timeline and ramp it up and down. Once we found that system, it was exactly what we needed. My assistant, Craig Ferreira perfected it, took it off and worked on those individual scenes and customized all the dosimeter sounds.

HULLFISH: I love hearing all about that stuff. It’s like using the un-translated Russian P.A. announcement for the evacuation. The sound is part of telling the story.

SMITH: You don’t need any words. The sound alone is scary enough. I think it the PA works better as just a sound than it does as “attention, attention, evacuation, evacuation.”

On the evacuation scene, we really pared the sound right back. You don’t actually hear many of the sounds that would be taking place. You don’t hear any other dialogue. You see the old man from Episode 1 getting on a bus and you don’t hear anything he’s saying. You see the nurse from Episodes 1 and 2 pleading with the soldiers and you don’t hear any of the words she’s saying. But you do hear the people move, the shuffling of people, the vehicles, the buses taking off. It was a very restrained use of sound — just picking up particular sounds to give a feeling, like a siren of a car driving past. Just being very minimal with it.

HULLFISH: We talked a little bit about structuring. You were saying how close the structure is to the way that it was scripted.

SMITH: There’s that commonly used saying that a film is written three times, once by the screenwriter in the script, then with the director on the shoot, and then with the editor in post. I agree with that, I believe in that, but 98% of this show was as written by Craig Mazin in the shooting script.

Of the other 2%, the one scene that changed most was the helicopter crash scene in Episode 2. That was probably the biggest scene that we had to re-work. I was cutting that scene — or bits of that scene — for seven or eight months. From the first rushes that come in, to when we finally locked it. It might have even been longer than that because the VFX were right at the end. And I struggled. There were lots and lots of different bits for that scene that came in separately on different days, and there was some second unit stuff that came in. I tried to cut all that together and I found it really, really hard. It just wasn’t working for me. And you do have these anxieties – “Shit am I doing it wrong?” – but one thing I do believe in and do take solace in is trusting the process. It’s going to be wrong, but you will get there. You just have to work it through. Work it through with your collaborators. Work it through with your director, your producers, your writer.

I remember we got through the end of the shoot and I had this assembly and I really hated it and I thought, “Oh God! What am I going to do?” I showed it to Johan, the director, and he agreed it’s a tough one. We played it for the writer and execs and everyone agreed. The original way that it was laid out was intercutting from ground to inside the helicopter and showing how things went wrong in the helicopter. We all came to this decision that the whole scene needed to just be experienced from the viewpoint of our guys on the ground. We need to experience this with our guys. This isn’t about being a Hollywood action film or disaster film. This is much more restrained — much more personal. So then Craig Mazin gave me a new eight-page script of how that scene would work from the rooftop — from Legasov’s point-of-view.

I remember we got through the end of the shoot and I had this assembly and I really hated it and I thought, “Oh God! What am I going to do?” I showed it to Johan, the director, and he agreed it’s a tough one. We played it for the writer and execs and everyone agreed. The original way that it was laid out was intercutting from ground to inside the helicopter and showing how things went wrong in the helicopter. We all came to this decision that the whole scene needed to just be experienced from the viewpoint of our guys on the ground. We need to experience this with our guys. This isn’t about being a Hollywood action film or disaster film. This is much more restrained — much more personal. So then Craig Mazin gave me a new eight-page script of how that scene would work from the rooftop — from Legasov’s point-of-view.

HULLFISH: You’re back to the idea of perspective again.

SMITH: Exactly. In the final cut, we do see it from other helicopters but we don’t go in close into the action. We’re holding back. And I think it’s more horrific. It’s more devastating. And it’s more in keeping with our style and grammar. When I watch it now I’m so glad I trusted in the process.

HULLFISH: Later on we see a montage of the abandonment of the city. Lots of shots showing emptiness. That’s great imagery to build something from.

SMITH: It’s all about the sun coming in in each of those places — in the classroom and in the hospital. The DP (Jakob Ihre) had this radiation metaphor with sunlight. Sunlight was kind of representing the radiation spreading out. And it was shot beautifully. I’m under the guidance on those montage scenes from Johan Renck, the director, and Johan is one of the world’s best commercials directors and music video directors. He’s a master of montage. If you type his name into YouTube you can see his commercials and music videos. I was under very good tutorship from him.

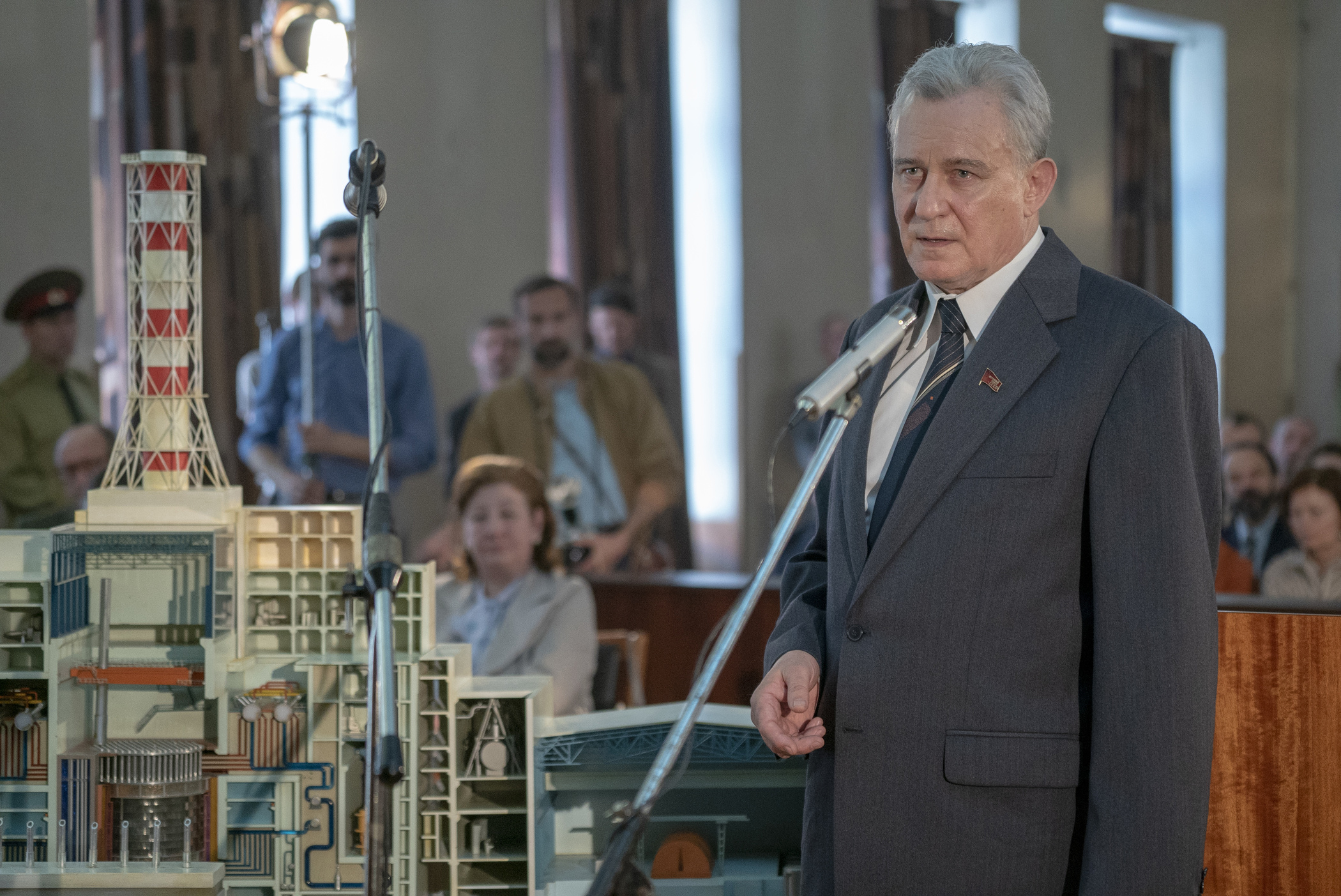

HULLFISH: When they’re trying to find three volunteers to go into the basement the General stands up and he delivers a speech. And at one point instead of being on typical coverage of him — an over into the audience or his face or a medium of his body you cut to kind of behind him looking at his profile in a window with the light streaming in. I loved it.

HULLFISH: When they’re trying to find three volunteers to go into the basement the General stands up and he delivers a speech. And at one point instead of being on typical coverage of him — an over into the audience or his face or a medium of his body you cut to kind of behind him looking at his profile in a window with the light streaming in. I loved it.

SMITH: It’s beautiful. It’s absolutely beautiful. If anyone cares to watch the episode again, something that I picked up on when reviewing my first assembly, is that from the phone call in the hotel room where they learn that the world knows that the radiation has spread to Frankfurt and Sweden – from then, all the way through the evacuation, and the talk in the big banquet hall, then through the Kremlin scene where they explained to Gorbachev that they need three men, then through the abandoned Pripyat, and then into that room you just described, Stellan Skarsgård’s character Shcherbina barely says a word until that speech. This arc of his realization from the phone call in the hotel room to him standing up and giving that speech — that’s amazing!

So, I went back and cut every scene through that arc from Shcherbina’s POV. Just his point-of-view, just do it and see what we get. His performances were amazing during those scenes — from him clicking his pen as he waits nervously for Gorbachev to come in or just sitting there totally lost as they describe what’s got to go on. You see all these little tiny brilliant bits of performance, and there were bits that if I’d just gone for the scripted words of dialogue, I would have overlooked perhaps what Stellan was doing. Doing a pass where I just cut it from that character’s point-of-view and just finding all the things that Stellan was doing was really instructive to get the best out of those scenes. And then, of course, you balance it back out afterward. You make sure that you bring in the other characters — that you tell their stories as well. But certainly, I feel that that little arc is made so much better in the edit, or through the edit, by doing that point-of-view pass, so that when he does stand up and give that speech it has all the more impact.

HULLFISH: I want to point out to younger editors the importance of what you were just talking about with editing the scene from just his perspective. You knew all that work of cutting the scene from that person’s perspective wasn’t going to end up with just that scene from that person’s perspective. You were doing it as part of a process you were going through. You needed to do the work even though you knew the work itself wouldn’t eventually be used.

HULLFISH: I want to point out to younger editors the importance of what you were just talking about with editing the scene from just his perspective. You knew all that work of cutting the scene from that person’s perspective wasn’t going to end up with just that scene from that person’s perspective. You were doing it as part of a process you were going through. You needed to do the work even though you knew the work itself wouldn’t eventually be used.

SMITH: Exactly. It was a technique that was taught to me when I was an assistant and my editor would say, “Go and cut that scene from this point-of-view or show me what this person is doing.”

HULLFISH: I’ve heard this technique used of cutting just a close up pass or a wide shot pass.

SMITH: I remember reading in one of your interviews — I think it was Joe Walker — who suggested cutting a scene backward so you don’t get stuck in a rut. How can you do something fresh to find another way of doing the scene? My approach to that is to pick a different character. Cut it from someone else’s point-of-view.

HULLFISH: There’s a great scene in Episode 4 that I wanted to talk about, with that old woman milking her cow and a soldier comes to evacuate her when she goes into a monologue. During the monologue you don’t watch her do the monologue, you cut to pieces of her life or her environment as she’s talking. Just tell me about constructing that montage or that scene.

SMITH: When that scene first came in, I probably did it the boring way, used some of those shots at the beginning as an establisher to the area that she was in, then used some of those shots at the end or whatever. Then I think I tried a cut where I didn’t use very many of them at all and just stayed with her. In this case, it was a suggestion from Johan. As soon as she’s started talking, and we’ve got into it, try those shots in her house and use those to tell the story. Again with Eisenstein’s theory of montage, what those different shots mean, it’s what they convey, when they are put next to each other. So that idea came from Johan, and then I was given the freedom to take that and explore it.

I’d never worked with Johan before, but the working relationship that we created, the way that we’d work – he isn’t one for spending time in the cutting room – he would get the cuts sent to him, and then come back with notes and ideas on how we could approach a scene differently if he wanted a different take on it. And then let you try that.

I’d never worked with Johan before, but the working relationship that we created, the way that we’d work – he isn’t one for spending time in the cutting room – he would get the cuts sent to him, and then come back with notes and ideas on how we could approach a scene differently if he wanted a different take on it. And then let you try that.

HULLFISH: Tell me about your approach to notes and your feelings about that advice from him to put those shots in the middle. Seems like great advice, but what if that’s not the way you cut it in the first place, and you didn’t think that was a good idea. Would you have explored it? Just because obviously the director told you to do it?

SMITH: You know, I really love notes to be honest, it’s a weird thing to say perhaps, but there are probably a lot of editors that do. It’s a new task, “go and try it this way”, great, now go and explore this other way. Because really, there are infinite ways that you could approach anything, you could approach it with only music for instance. So having a little bit of “this is what I want” is great.

I try to really listen to what it is that someone wants. Whether that’s the director, whether that’s the writing team, what the execs want from something – really listen to what it is they’re asking of you, and asking of the edit. And try and think hard about the response to that, and giving them what they want. Sometimes you get a note, and it’s better to just understand the problem then it is to do the note. Because the solution may not be correct, but identifying where they are falling out of the experience, and then address that, look at that, explore that.

And try everything. Even if it’s a note that you don’t agree with, try it. The process is only going to make it better. What notes are doing, is giving you an opportunity to possibly make it better, right? So I love that. If they’re going to give us the time to do the notes, keep giving me notes! Keep giving me other ways that we can explore this.

In my own reviews, I give myself notes, give the edit notes, give the edit notes on what could be better in that scene. I mentioned the reshuffle at the very beginning, swapping two scenes around in Episode 2, to put these two characters together. That was something I saw during reviews, I sent a note to Johan and said “Look at this, what do you think of this, if we did this …” and he was like “Oh I love it! Yeah, let’s do that!” So just as much as I’m getting notes, I’m giving myself notes, and giving the edit notes, and I’m part of that process as well. I’m forever reviewing, revising, trying to see if there’s a different way or a new way of doing the scene.

In my own reviews, I give myself notes, give the edit notes, give the edit notes on what could be better in that scene. I mentioned the reshuffle at the very beginning, swapping two scenes around in Episode 2, to put these two characters together. That was something I saw during reviews, I sent a note to Johan and said “Look at this, what do you think of this, if we did this …” and he was like “Oh I love it! Yeah, let’s do that!” So just as much as I’m getting notes, I’m giving myself notes, and giving the edit notes, and I’m part of that process as well. I’m forever reviewing, revising, trying to see if there’s a different way or a new way of doing the scene.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about the tools and techniques, specific ways you have of working with material.

SMITH: There’s a tool that I use a lot – an awful lot – it’s called “trim to fill”. I don’t think many editors use it. It’s a terrible name for a tool – in Adobe Premiere it’s called “rate-stretch”, and it’s a much better implementation. But for people who don’t know what it is, it basically allows you to take a moment, and stretch that to last as long or as little as you like using the trim functions. For me, it’s one of the purest reductions of what we as editors are doing. It’s editing – but with a single shot. It’s not editing with two shots – it’s not montage – it’s just taking a single shot, and still being an editor with it.

It’s hard to imagine really, but if people wanted to try it, they would take a shot of one of their characters, and a moment when the character isn’t talking, and add a cut point at the beginning of that moment, then add a cut point at the end of that moment and then drop the “trim to fill” effect on that segment. Then trim it out, and roll it back in. And watch what that does. And you suddenly become this “master of time”! It’s completely magical, and it is exactly what we are doing as editors all the time. That’s what we’re trying to do.

And don’t get me wrong, it’s not to manipulate the actor’s performance, that’s not what I’m trying to do – at this level, those guys are the masters of their craft – it’s about manipulating time. Especially when it’s point of view, or rhythm and pacing, having this ability is magic.

HULLFISH: Is that true? I usually use time-warps to be able to pull off the same effect. I’m cutting a movie where the person spends a lot of time on the phone talking to someone and the person that was delivering the lines on the other side of the phone was too slow. They were waiting for the actor to speak then looking down at the script and then reading the line, and it made the pauses too long. So I use something similar to what you’re saying because I couldn’t have that actor wait so long between their lines because the line on the other end of the phone was not that long.

HULLFISH: Is that true? I usually use time-warps to be able to pull off the same effect. I’m cutting a movie where the person spends a lot of time on the phone talking to someone and the person that was delivering the lines on the other side of the phone was too slow. They were waiting for the actor to speak then looking down at the script and then reading the line, and it made the pauses too long. So I use something similar to what you’re saying because I couldn’t have that actor wait so long between their lines because the line on the other end of the phone was not that long.

SMITH: Yeah – How are you doing it?

HULLFISH: It’s with “time-warps” in between them. But I’m going to have to try this “trim-to-fill”.

SMITH: Once you’ve tried it, you’ll be thinking “Why didn’t someone tell me about this?!” Honestly, it’s the worst name ever – “trim to fill” is a terrible name – but once you drop that on, then that bit, as you roll out the trim it slows it down, or roll it in and it speeds it up.

Going back to Eisenstein’s theory of montage, he’s actually got two stages to it. There is the first stage, which is the placing of shots – which shots go next to which shots and how that conveys meaning. And then the next lesson is what he calls “metric montage” which is about the duration and rhythm of those shots. So I really feel that his theory of “metric montage” is taken to another place with the use of “trim to fill”. I’m sure that if Eisenstein had had “trim to fill” in his edit toolbox he’d have loved it!

Another thing that I like to do when I’m watching my dailies is to add markers. But if you drop a marker on your dailies sequence, it’s just dropping it on that sequence – there’s no further match back of that marker, onto the source clips themselves. I’d love it if Avid had an option to “add marker to source”.

So I use one of those gaming mice, and I love it, I think Eddie Hamilton talked about it in an AOTC interview, the Razer Naga. With that, you get to write macros.

So as I’m watching a sequence when I press a button, it activates a macro, that matches back to the source and adds a marker to the source, then goes back to the timeline adds a marker to the sequence and then it continues to play.

So in order, it’s – match frame, add marker, toggle timeline, add marker, play. Okay?

HULLFISH: Love it. No, I totally understand. It’s your workaround to do what you want to do.

SMITH: It’s my workaround – as I’m watching a sequence of dailies I can add a marker. It will then put those markers on my clips in my bin so that when I open my clips from the bin, later on, I can still see the moments I’ve marked. And you can write the macro so it happens instantly – as you’re watching you’re just pressing the button on the mouse. I even have a few different colored markers to choose from. I press a button on the mouse and it just continues playing, but all these markers have been added to my source clips. If Avid can do this without me having to write a macro I’d love it.

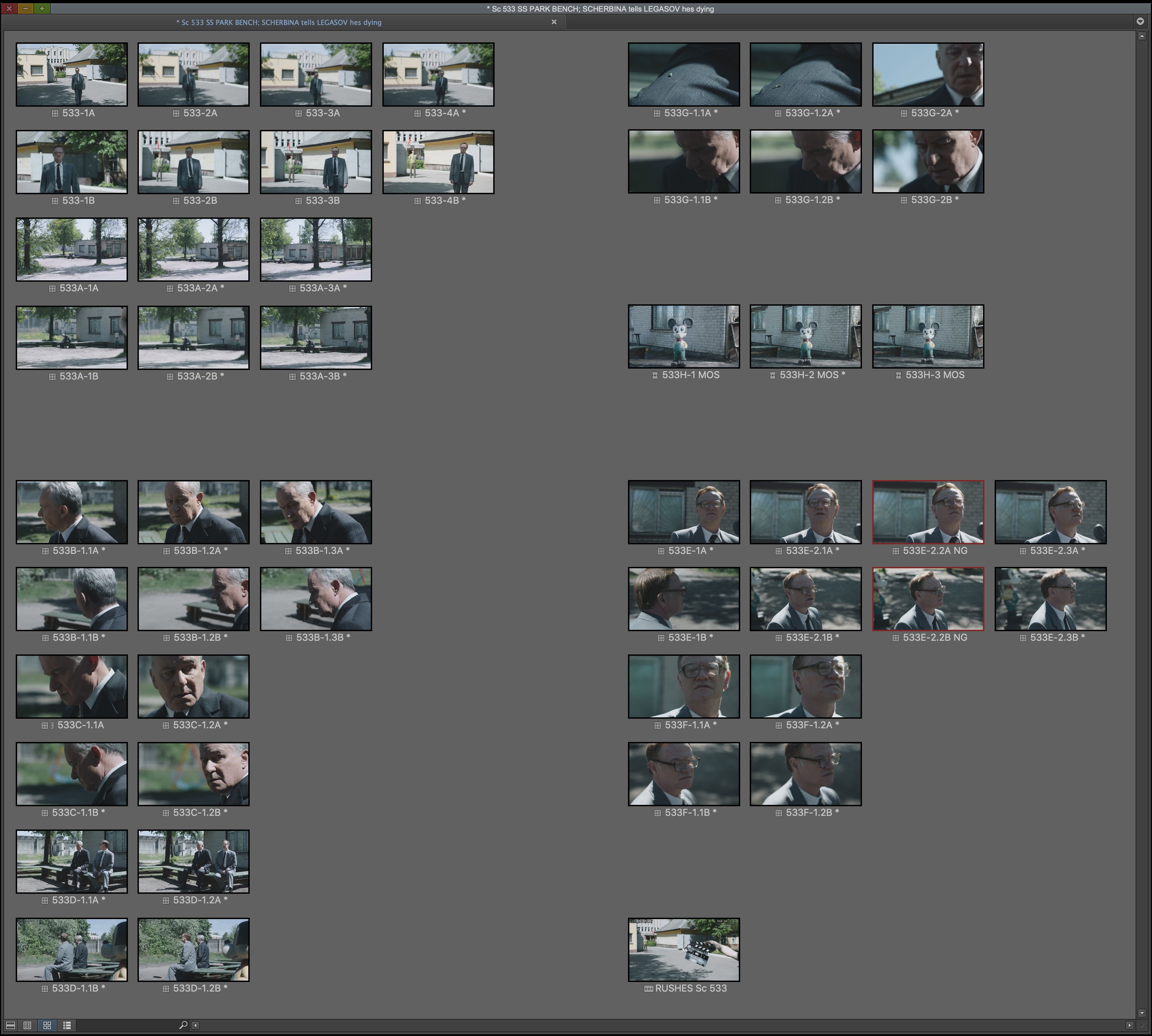

What else do I do a lot? Oh here’s another one – I looked up “bin organization” in your book and how different editors lay stuff out. If there’s a reset during a take, I ask the assistants to split that take into several clips. So Take 1 would become Take 1.1, Take 1.2, Take 1.3, so then in the bin, you can see how many versions you have to choose from.

Then for multi-camera stuff, I’ll get them to duplicate the multi-cam-clip, and change the thumbnail to show each camera. So again you can see all the versions that you have. If it was a multi-cam shot, I don’t have the single-cam clips in the bin, as I like the ability to change the camera on the timeline.

I read all of your interviews, look at the screengrabs, and a lot of editors use this “T formation” where they’ll show a single clip of the A camera and the B camera, and then they’ll have a run of the multi-cam clips. I’d much prefer to just duplicate the multi-cam-clip and change the thumbnail. You can turn on little clip icons in the bin, so you can see it’s a multi-cam-clip.

I also use frame borders, so my assistants would color it red if it was no good. So you wouldn’t bother opening that one.

I try and keep up with all the advances Avid does and incorporate those or use those. They added mute and un-mute as a button, I use that all the time now, and I’ve put that on the shortcut keys on my mouse. I’ll use those new mute options for auditioning with a director different versions of a cut. I’ll leave the versions or options on the sequence, and just mute/unmute them.

HULLFISH: I want to stop for a second with that because when you’re not talking about muting the sound of a track you’re talking about muting the clip right?

SMITH: Yeah. It might be muting a sound clip, or muting a video clip. That’s a great tool I’m very happy about.

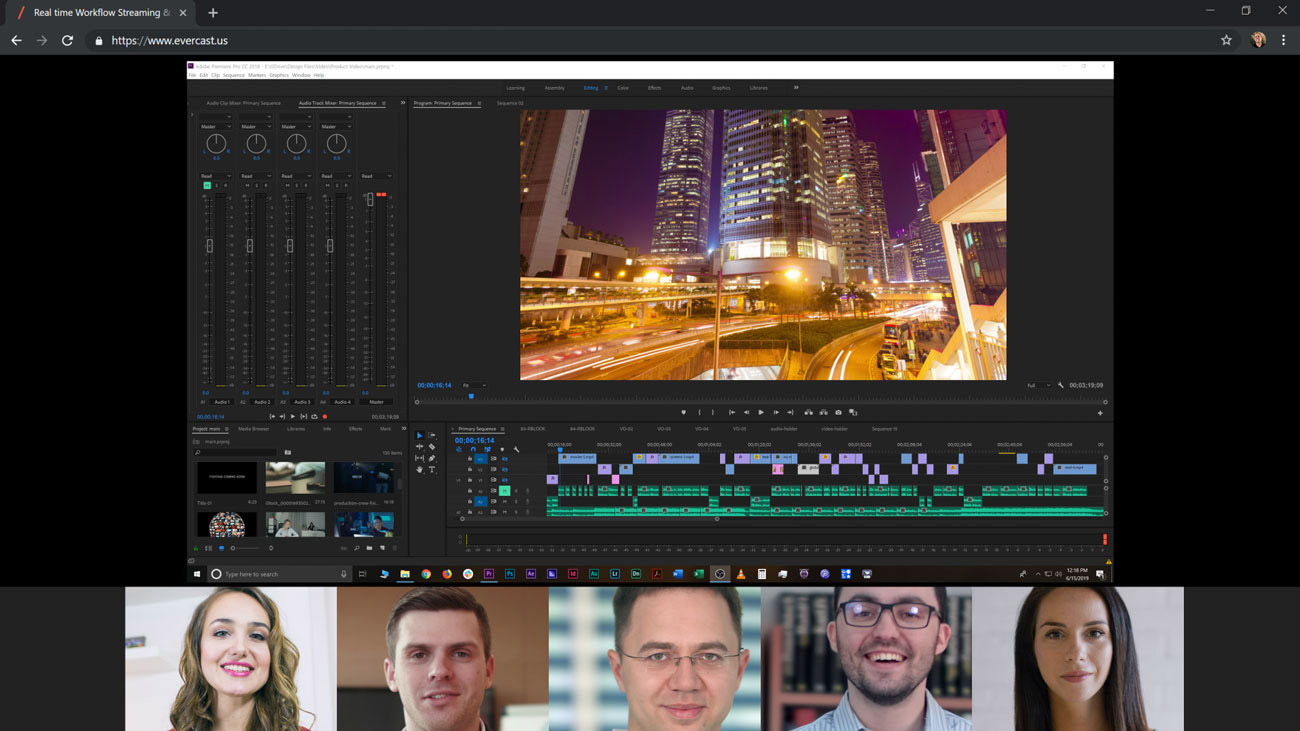

And then I guess the last thing that’s worth plugging for the guys that the make it, is a system called Evercast. When we started Chernobyl we had Craig Mazin, the show-runner in Los Angeles, we had Johan Renck the director in New York, we were shooting in Lithuania, our composer was in Berlin, and we edited in London. So it was hugely international and lots of people wanted to be able to look at things or view things. And Craig Mazin asked us to find a way to best emulate being together in the cutting room. He would stay in Los Angeles, and we could stay in London, and he wanted to be able to see the timeline and the bins and the clip monitor and hear the sounds, communicate with us all, in real-time.

I’d seen different boxes that sling the HDMI or whatever across the internet. But I’ve never had a system that could do all these things in real-time, you’ve got Team Viewer but it doesn’t really do this. We gave this problem to our facility providers HireWorks, and they went off and did a load of research and came back to us with this new tool called Evercast, which had only really just started out. Evercast is made with editors and is for editors. Roger Barton, he’s done Transformers and Terminator films, and Pirates of the Caribbean. So he may talk to you more about this, but he came on and demoed it to us with their team and during the demo, I was blown away, it was everything we wanted and more, and everything that you could try and catch them out with, they’d thought of a solution to.

So what it basically does is it gives anyone the ability using Google Chrome to log in and see your desktop, in real-time with, with HD video, and they can set up as many of those as they like so you could do one for your monitor that’s got your timeline on it, one for your monitor that’s got your bins on it, one for your client monitor, you can do one for your webcam, and you can all communicate in this group session, multiple people can log in at once and do a conference call where they can all see these things.

HULLFISH: How do the people who are watching it see multiple monitors all on one laptop screen?

SMITH: They have a single window with thumbnails down the bottom where they can flick between, or you can open another window, because it’s just a Chrome browser window, so you can have them on several monitors. And they’ve got this option where you can get Evercast to intelligently choose for you. So if you stop the playback and someone then starts talking it will go full screen on the person who’s talking with a webcam and then if someone else starts talking it would switch to their screen. So it’s almost like it cuts the conversation for you between the cameras.

Then beyond that, give them huge credit for this, they knew who their market was and they’d done all the things they need to do to satisfy Disney or HBO’s security requirements. They’ve already gone to HBO and said here’s how we built this. Here’s how we do this, here’s how we’ve tested this and they’ve got that sign-off. So if you’re working on a Disney show on HBO show you can get a license to Evercast and communicate and collaborate in this way.

As a tool that, I don’t want to get all lordy about it, but it’s one of those that can improve the quality of our work and it can improve the quality of our lives. You know people get to go home and see their kids at night. You know people get to work together in new ways. I think it’s special.

HULLFISH: I work in Chicago a lot, with producers and directors that are not in Chicago, and a lot of times I’m having to use a workaround. This sounds like a great opportunity for me to be able to share my work with distant producers and directors.

SMITH: It’s amazing. All they need is a wired internet connection, and then Google Chrome and they just log into the room, give the password, and then they get the options of all the monitors that are in the room. They don’t need any other hardware at their end.

HULLFISH: That’s just great information. I love all that technical geeky stuff. Did you see the recent tutorial that I did about using the iPad to control the mixer? You mentioned Eddie Hamilton, and I’ve been in communication with Eddie about it and he sent me his exact setup and he says he actually prefers it. Obviously I was teasing him – I’m like “Come on, Mission Impossible doesn’t have the money to pay for an Avid Artist Mix?”, when he goes “No, they do of course, but I like having an iPad because the form factor is so small, and I can easily move it out of the way”, so he actually does all of his mixing using an iPad connected to his computer. It’s a free app for the iPad, called ProTools Control.

SMITH: I have tried it, a while ago, but I couldn’t get it to work.

HULLFISH: I did a little tutorial on ProVideoCoalition on how to do it. I showed how to download it. The software you need because you need to download EuControl for the Avid and then you have to set your MIDI composer settings, and then your systems have to be on the same Wi-Fi. Eddie was saying “Hey look, I can’t have my computer be on a Wi-Fi network, I’m editing Mission Impossible!” And so he showed me how to do it with hardware with a bunch of adapters to go from the iPad lightning adapter to USB, USB to Ethernet, Ethernet into his computer. So he’s hard-wired to his laptop. He doesn’t have to use Wi-Fi to get the ProTools to the computer like I do.

How to control Avid Media Composer’s Audio Mixer in real-time with an iPad

SMITH: Did you have an interview with one of the guys from The Hunger Games who had a touch screen setup. Is that one of yours?

HULLFISH: I did interview the Hunger Games guys. That was Alan, he uses a Wacom Cintiq tablet.

SMITH: That’s incredible. One of the big things coming is Apple has included a screen sharing to iPads feature, and this ability to use your iPad as a Touch Screen built within Mac OS, so that’s very cool. If you could put your bins or mixer on that.

Sometimes, when I start talking about all this geeky stuff, some editors aren’t into it. But you know what, it’s not about thinking that the tools make you the editor or anything like that, it’s definitely not that. I agree with them. What I’m trying to do, I guess, is remove the tools. If the tools become so good that they fall away, so that as an Editor you can do what you want to do without having to think about the tools – Eddie Hamilton using an iPad to do his mixing – that’s exactly what he’s doing. He’s removing layers of friction between him and Editing. It’s the same with macros and it’s the same with “trim-to-fill”. It’s the same with short-cut buttons and all those things. It’s about how can I, as fluidly as I can, get the idea in my head from my head into the edit. And therefore I hope I justify geeking-out over tools!

HULLFISH: You can always justify geeking-out over tools with me. That is not a problem. But I definitely agree that some people would say “That’s not what I’m interested in, I’m just interested in rhythm and pacing and montage”. So great – how do you montage anything without touching a tool?

HULLFISH: You can always justify geeking-out over tools with me. That is not a problem. But I definitely agree that some people would say “That’s not what I’m interested in, I’m just interested in rhythm and pacing and montage”. So great – how do you montage anything without touching a tool?

SMITH: I love that as well, I could listen to someone talk about montage all day. But then as you say, how do I then achieve that as fluidly as possible.

HULLFISH: Abraham Lincoln once said, “If I had six hours to cut down a tree, I’d spend four hours sharpening my ax.” That’s what we’re talking about when we’re geeking-out like this. Sharpen your ax and it makes the cutting so much easier.

SMITH: That’s brilliant. I love it. Sharpen your ax enough, and it will fall away. That tree will just fall down.

Thank you Steve, and thank you for doing this, all the time, I read all of your AOTC interviews. It’s such a huge asset and library to all of what we do, and to have an opportunity to talk to you and possibly contribute to that library is an honor. It really is.

HULLFISH: Thank you so much, Simon. You are definitely part of the library and a very worthy part.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now