Chris Dickens, ACE, won the Oscar and an ACE Eddie for Best Editing for Slumdog Millionaire. He was also nominated for an ACE Eddie for Best Editing for Les Miserables. Other work includes Shaun of the Dead, Hot Fuzz, MacBeth, The Man with the Iron Heart, and Steel Country.

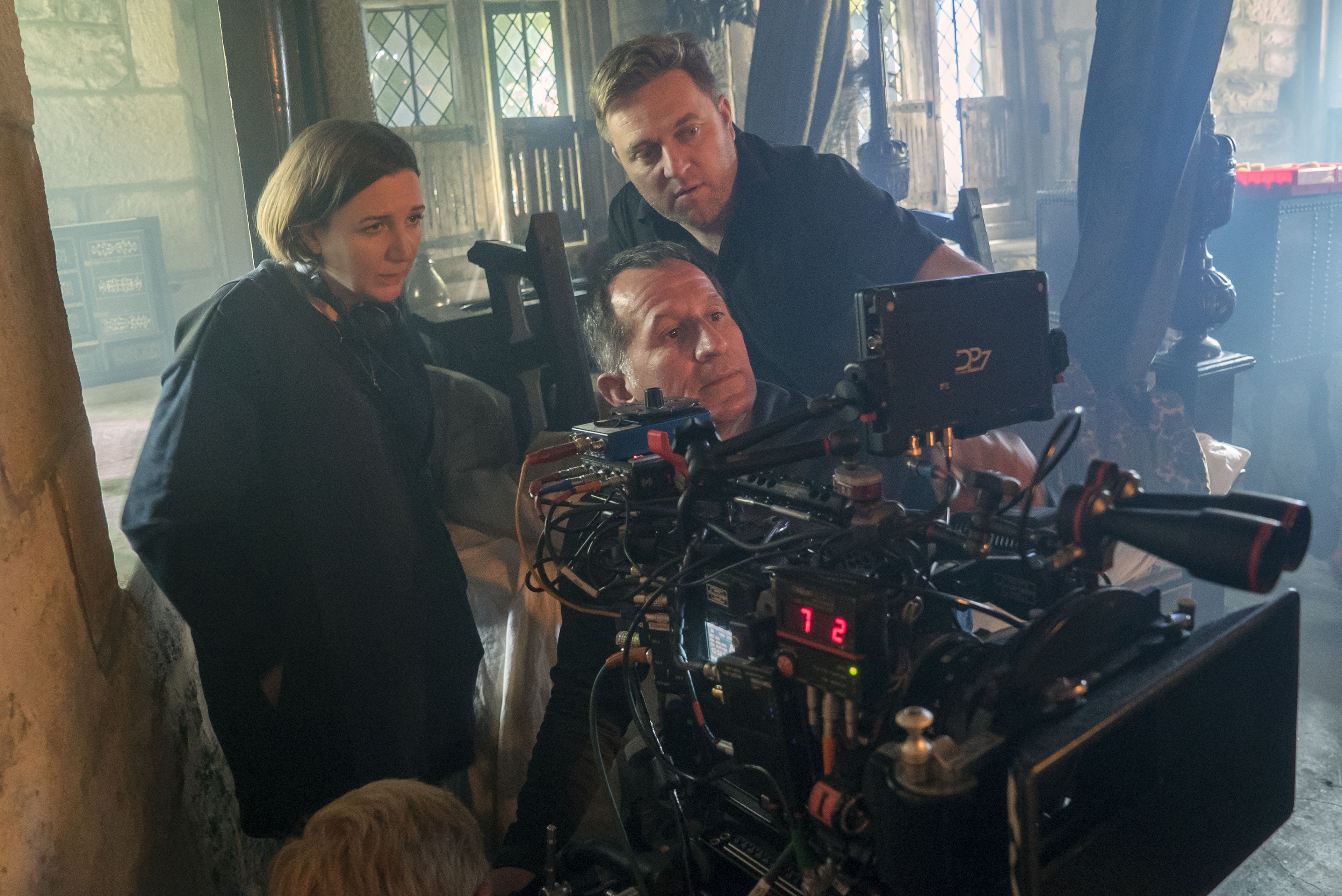

Art of the Cut talked with Dickens for his latest feature, Mary: Queen of Scots.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: I saw in your IMDb filmography that you started out doing sound editing.

DICKENS: Sound was the thing I was originally interested in doing, but that was mainly because I didn’t think I’d ever get to do any picture cutting. I thought sound editing would be a way into the biz. I suppose it was the thing that I got interested in first and so when I started picture editing, I realized that I had a lot more tools to play with. Now I suppose I don’t do as much of the actual sound editing as I used to. I used to do a lot during the rough cut of the film and the director’s cut of the film.

Now, I obviously have a lot of help from people doing the actual sound work: sound editors, sound designers. But what I really like to do now is keep the creative side of the sound in my head because for me it’s a vast part of the picture. I am always thinking about how sound can contribute to the scene or movie emotionally to create a feel of what the story is — where the story is going. Of course, that always gets changed and that evolves as you go through the process. First, you’ve got the editor’s cut, then the director’s cut. The whole soundscape evolves slowly. So I’m very interested in that and of course, with the way music works as well with that but I’m quite interested in the crossover between SFX and music and combining them so that’s why I like to do a lot of that in the cutting room now and we have the tools to do it.

HULLFISH: When you’re imagining that sound work is that because you’re trying to leave room for the sound — or space?

DICKENS: Yes, but also it informs the picture cutting. It has. It’s like if you’re cutting a sequence and you’ve not got the visual effects or any music to play with. Say, for instance, the scene looks bad because it’s just a lot of green screen. What I find tends to happen is that you tend to cut it down because you don’t have the images, but when you get the visual effects you think, “Oh God, I’ve got to extend every single shot because it looks beautiful” but often that happens quite late in the process. It can happen the other way around: the visual effects aren’t good enough and you’ve got to cut them down.

So that’s the same as sound. You just need to be thinking about what’s going on in the soundtrack because it helps with your cut. Like, “Oh, I need to hold on this sequence a beat more or this shot a beat more, or the energy of the picture cutting isn’t quite right,” but I have in my mind that the sound will change it. Often it comes a little bit later in the editing process after we’ve done the first cut of the film. It’s then that I start thinking about how scenes are linking together. How we’re building the film as a whole. When you’ve got the actual sound on board it changes again. It’s constantly changing.

HULLFISH: That’s the thing that I think some young editors might not fully grasp: It is a process that takes place over months. So you’re constantly revising. You have to remind yourself that you can’t be married to it at an early stage.

DICKENS: Exactly. I mean. It’s just the process of trying to educate yourself not to be married to it. Obviously, the process is different with everybody you work with and so you have to understand the people — particularly the director — you’re working with because it’s such a close relationship. You have to be open to another way of doing things.

HULLFISH: Right. You’ve worked with director Edgar Wright a number of times, but you’ve also worked with a wide variety of directors only once. I’m sure, with your schedule, directors try to use you again, but you’re tied up on another film, but is your relationship with a director different than with someone you’ve worked with multiple times — and how?

DICKENS: Obviously if you know someone, you understand their thinking more. A new person, you have to get to know. I’m working with a director, Dexter Fletcher, who’s an actor actually and it’s a musical that we’re doing and he’s done a number of films with other editors. I only just started with the director’s cut with him and I’m trying to understand the way that he works. He’s very different from Josie (Mary, Queen of Scots director, Josie Rourke). She’d never directed a movie before. That was a very different way of approaching it. I was teaching her some things about the process, but also allowing her to flex her muscles as a director and bring her unique ideas to it. I’d like to work with the same directors more but it just doesn’t happen.

HULLFISH: Josie looks like she’s done a ton of theater. What kind of things happened that were surprising and original because of her lack of experience with film directing and what were the challenges?

DICKENS: She was not afraid to have a certain theatricality to certain scenes and in a way that was refreshing. When it came to the edit that was difficult because perhaps there was not a lot of movement as you might normally get. In the theater, it’s much more about the dialogue and the delivery of the dialogue. Whereas in a movie it’s not just about that. It’s about visuals and a look — silence. All of those things. That’s what we had to work on. I really believed in her vision for the film and it was a sort of feminist vision, essentially, about these two women. And I really wanted to do justice to that.

HULLFISH: Tatiana Riegel just cut a film with a fairly feminist bent — a strong female lead character (two actually). I asked her — hopefully not in a sexist way — whether she thought the director chose her because she was a woman and wanted her female perspective on it as an editor. The director of that was a male and she thought that it was great to have both perspectives in the editing room. On this film, the director is a woman and she chose you. Any thoughts on that male/female perspective thing on a film like this?

DICKENS: I think they did look at women as editors for this film. It might have been a question of balance. I think that I’d have to be a fairly insensitive man not to understand what the demands of the story are. It all comes down to that and I think a man or a woman could do the same. It’s like a woman editing an action movie — it would be very sexist to say you can’t do that. There are great women, brilliant editors who’ve edited all kinds of movies, whether it’s macho stories or male-oriented stories — women can do that, so why can’t men do the other way round? I think it’s just about the sensitivity to story and ultimately it’s only about that. You make your decisions based on the demands of the story and the vision of the director. I think a mixture is good. I don’t like it when my editing team is either all women or all men. I find it’s good to have a mix. It just works better.

HULLFISH: Was the use of shot size in the film grammar of the edit an issue with a director who came from theater?

DICKENS: My first instinct was to try to steer away from anything that looked theatrical. I realized I was trying to make it more movie-like — more close-ups and mixing it up and she was doing the opposite. She wanted it to look a little bit stagey because that’s how Mary, Queen of Scots was. She had a very theatrical approach. She used to lay on these kinds of pageants and shows for her subjects. It annoyed a lot of the men around her, but actually, that’s the way she was and so I understood. Josie wanted that at times. I had to sort of swallow my pride slightly and see that we’re not necessarily going with close-ups the whole time. I think shot size was ultimately more of an issue when they were actually filming.

HULLFISH: Did you find when you were editing during dailies or rushes that you were asking for more coverage?

DICKENS: There were a number of action-oriented scenes that I was worried about coverage, but Josie wasn’t interested in doing them like that. She said, “I’ve seen all this stuff, like on Game of Thrones, and I’m not particularly interested in that.” She was interested in a more intimate story. At that time, I was saying, we need more shots to make this sequence work. But when we got to the director’s edit, I found out that it wasn’t important at all. What was important was her view of it. If I’d have known earlier what her vision of it was, I could have helped much more. With all these things, you’ve got to work within your budget. If you’ve got six months you work within that and you get a lot more stuff but if you only have three and a half months — which this was — then obviously you’re more limited in what you can get.

HULLFISH: You’d mentioned that you could have helped more if you’d understood her vision at the start. How much time did you get with her before shooting? Do you feel that generally, pictures could be better if there was more up-front interaction between the editor and director to get a good download of their vision?

DICKENS: Some do. I had a good chat with Josie. I got a good chance to get what she wanted in terms of the story, but not the visuals. When I worked with Edgar Wright, he would put together whole reams of stuff for us to watch, like influences. He’d show us other movies that he loves and is trying to emulate. Other directors, like Danny Boyle, would say, “Watch these movies. This is what I am interested in.” Occasionally it happens and it is refreshing.

I’m working on this Rocketman film about Elton John and I was a lot closer than normal, partly because they were in a studio next to us but Dexter Fletcher would come in a lot. A lot of directors want to see stuff as they’re filming, but he wanted to see it and discuss it in more detail and I loved that because then you really are involved in it. And pretty much everything I suggested that they shoot they went and shot. I’m really not used to that.

HULLFISH: I saw you have some documentary films in your background. Tell me about that and what different muscles you are flexing when you’re working on one type of project compared to another.

DICKENS: I’ve done a bit of documentary. I’d kind of like to do more, because what documentary is so good at — and you are using the same main muscles — but there are not so many rules, essentially, because when you get to the edit you have to make the film. You have to be far more flexible and you almost have to find the film within it and you have to be far more disciplined with yourself about letting go of stuff. Cutting stuff out. Literally going for the story or going for the essential. And also not being tied up with convention. It’s similar to the comedy editing I’ve done. I’ve worked with a lot of very creative people with that and with comedy, the rules don’t really apply. Whatever idea in the comedy side of things makes people that’s it. They don’t really care if the edit is a little bit rough or that it looks a little bit bumpy as long as people laugh. That’s the aim. To get people to laugh and to get a reaction. You’re jettisoning your instincts to tidy things up and smooth things.

It’s similar to what I find with soundtracks. Often the sound on my picture editing is quite rough because you’re just using production audio. But the sound team tends to clean everything up and it often takes all the energy out of the film.

I found with documentary that it has an inherent energy because it’s real and imperfect. What the camera misses or doesn’t see is just as important as what it does see. With documentary you just jump cut. You don’t have any choice. You’re cutting straight for the story essentially. So I do like it. Id love to do a bit more of it.

HULLFISH: I think it’s fascinating that you tied comedy to documentary — that they have similarities. I just watched Hot Fuzz recently, which you cut. It had great edits in it, but you’d never be able to do some of those edits in Mary: Queen of Scots.

DICKENS: No. For sure. Mary: Queen of Scots wasn’t shot like that.

HULLFISH: Right.

DICKENS: It literally wasn’t shot like that. It’s very hard to go against what’s shot: the pace, the acting, the pace of the camera. John (John Mathieson, DP) shot in quite an elegant way. Beautifully and with not a great deal of camera movement. No hand-held. So your editing style comes from the material. You don’t really impose it. Edgar has an approach where he plans it a bit more, like a musical. Baby Driver, he planned a lot of that stuff. What he wanted was something fast and witty and the way it was cut was sometimes designed to be funny. He was into whip pans, jump cuts all these things. He would plan it, but he would also plan for changing it. Therefore you’ve got something that’s got quite a lot of energy and movement, and therefore the edit has more energy and movement and wit, for want of a better word.

HULLFISH: You’ve done big budget and small budget films. Is there much of a difference in your working style? Do you have to approach scenes differently because the amount of time you have to work?

DICKENS: A bit. I haven’t gotten into the really big budgets, and when I have, I found them a bit difficult because the demands are that they look a bit more finished more quickly.

HULLFISH: Oh, interesting.

DICKENS: The demands are greater because you’ve got more money being spent. You have a bigger team on board. So the decisions you make are maybe not quite as brave in a way. Whereas I find with a low budget you haven’t got that much time in the edit but you’re kind of freed in a way. You’re freer because they’re not expecting as much.

HULLFISH: Is the same true with TV? You’ve cut some TV in the past.

DICKENS: I’d love to do some TV now because I think they’re better. They’ve got more money and the quality is way up there. They’re creatively doing what cinema used to do. But, yes, it was faster. And sometimes working quickly is good. It is better in fact, occasionally. When I worked with Danny Boyle he was a great person to work with. He said, editing itself doesn’t take very long, but THINKING about it, deciding what you’re going to do takes a long time.

I always watch all of the material and think about how it would go together and often you only really discover how you’re going to approach a sequence until you’ve seen all the dailies. Sometimes the last shot you see is the key to it. Some days, where you get a lot of rushes, it could take five hours of viewing. And then you realize you’ve got to get something cut by the end of the day. You’ve only got two or three hours to do it. And often, if you’ve watched it all, you CAN do it very, very quickly. But often if you skip takes, it takes longer. I have a theory that watching dailies is itself is a skill set.

HULLFISH: How do you watch dailies or rushes?

DICKENS: You have to be patient. If they shot a lot of cameras and there are a lot of takes, it’s very hard to watch everything. But I try to. I have a process and I think it’s very important. You almost experience what they experienced on the day. You get to know what the development of it was. So I watch. I just go through and I mark. If I haven’t got much time — if I really have a limited time — and I have to get a sequence out, then I will only go with what they selected on set to start with and try and make a quick cut. I watch everything and it’s like a memory bank. I mark the things I like with a marker and then I remember it in my head. I say, “OK, there are three different types of performance in that and I wonder which one’s best?” So I’ll just go for one. And then later, inevitably, you find when you get the film together — there’s a scene like this in Mary Queen of Scots. It was very performance-oriented. There was a clip that the performance didn’t seem right, and I went back to a performance that — on the day, on set — they didn’t think was right. But I remembered that that take was there.

HULLFISH: When you’re watching rushes do you put them in a KEM roll or are you just calling up each individual take from the bins?

DICKENS: I call it a lab roll. I put all the takes together and I trim off the boards (slates), so I’m not distracted by that and then watch it and then mark. And then I take out all the things I didn’t like. Save it. Trim out more things I don’t like. Save it again. Watch again. Trim out everything that’s not really good and then that starts getting into a cut. And I keep all these versions because inevitably when I get in with the director I need to watch the originals. I remember seeing editors use this process years ago and thinking, “That’s very painstaking and laborious! Why are you doing that?” It’s because sometimes you don’t have any inspiration at all, so you have to have a process just to get through the day — to do some work, to deliver something — even though it may not be quite right. And I find it always works if you’re patient: Watch everything and think. Often I try to look at a key take that’s really good and I think, “OK, that was a great performance and I’ve got two cameras, on it so I’ve got the bones of a sequence there. And I often build it around one take.

HULLFISH: The director’s selected take on the day is not even the selected take that THEY would pick if they sat down and watched them all at the end of the day, instead of choosing on set.

DICKENS: That’s true. And the selections are sometimes quite arbitrary. Sometimes they select it because there’s one little bit in it that they liked and often there’s not time to talk to the script supervisor about why they chose a take. It’s better to watch and make your own decision if you can. You have got to really explore the material — look through and see what you really have. And so that there’s no real shortcut.

HULLFISH: You’re doing Rocketman… you did Les Miserables. Even Slumdog Millionaire had musical sections. Can we talk about editing musicals?

DICKENS: Ultimately it’s always about the story. With a musical, I suppose it’s a bit like a comedy. Every kind of story you have to justify why almost every single thing is in the film at some point. Every line every shot. You have to have a reason for it. For instance, in a comedy, if something’s funny well that’s a reason it should be in. You don’t have to justify it on any kind of deeper dramatic way. It’s a good enough justification. With musical it’s that quantity, isn’t it? That’s a little bit more elusive, it’s like a feeling isn’t it? You can go off from the story, and as long as it’s entertaining. A musical sequence works if it takes you to another world — it might only be similarly related to the story but it was fun. So, therefore, that quantity is a bit different with a musical. You can’t be quite as logical about it. You have to be freer about it. I think this musical is a little bit more related to story in terms that the musical numbers tell a story. Most movie musicals are quite long. And I think it’s because you need to experience the music properly — the whole number — three or four minutes. And then you need the dramatic scenes as well so the whole thing becomes quite long. A three-hour musical doesn’t feel long.

HULLFISH: You’ve won and been nominated for several awards for your editing. When you are judging editing — as a member of The Academy, or BAFTA or ACE, what are you looking at to judge the editing of someone else?

DICKENS: Jealousy.

HULLFISH: (laughs)

DICKENS: It’s that I hate that editor. You know it don’t you? You think, “Oh God that’s good!” You are compelled to vote for it. I’m only partly joking. You think, “Oh God I wish I I’d thought of that!” Creative jealousy.

That keeps you creatively alive. That’s why Thelma Schoonmaker is always getting so many awards. Obviously, she’s working with Martin Scorsese and they have a great relationship. But every time you see his movies the editing has got some great ideas in it. That’s why she’s so respected.

HULLFISH: What in Slumdog Millionaire do you think your fellow editors saw that caused it — and you — to receive so many awards?

DICKENS: The whole film was good. It was like the combination of everything was good. The editing is just one of the things that got an Oscar. There are some movies that get Best Editing and nothing else, but rarely. Normally they get an award for best film or Best Director or something. I think those two go, don’t they? A well-edited movie, you’re not showing off. You’re bringing the whole thing together.

HULLFISH: Chris, thank you so much for your time.

HULLFISH: Chris, thank you so much for your time.

DICKENS: Thank you. Bye.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now