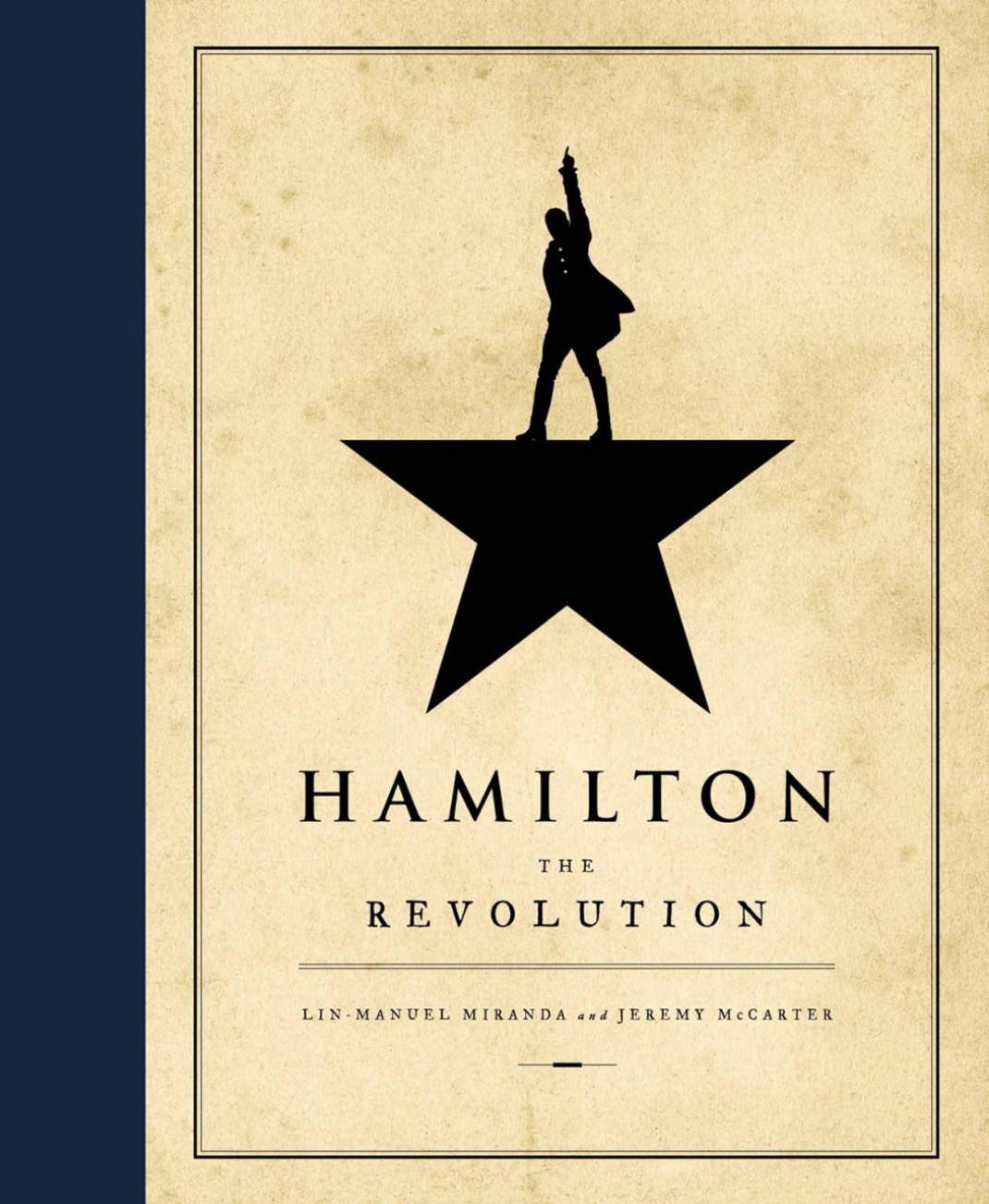

Hamilton may have upstaged Star Wars as Disney+’s most compelling content. Turning the blockbuster Broadway hit into must-see TV was not as simple as sticking a camera in the balcony and a microphone at the lip of the stage. Working closely with “The Cabinet” – Hamilton’s cadre of creatives, including creator Lin-Manuel Miranda, director Thomas Kail, and choreographer Andy Blankenbuehler – editor Jonah Moran shaped multiple performances into a single, seamless filmed experience.

How to balance wide-shots – crucial to an appreciation of the choreography – with close-ups of emotional moments? How to make it it’s own unique screen experience of the show, but also a document of the show itself? How to know when the most beautiful shot in the show must be sacrificed on the altar of story?

Moran’s background includes episodes of FX’s Fosse/Verdon, NatGeo’s Mars, and ESPN’s 30 for 30.

There will be spoilers… hopefully, you already know your history, or have at least seen Hamilton on stage or TV. To kick things off: Hamilton dies, Washington becomes President and the King is both pissed and amused.

This interview will be available as a podcast Tuesday night (July 14, 2020).

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: What kind of research did you do and how much did any of that inform your editing?

MORAN: Hamilton was already a pretty large phenomenon when I was hired, so there was a fair amount of information available to me. But, in preparation for this project, I was kind of being informed by whatever little tidbits I could grab from wherever especially anything coming from the creative team. There’s a beautiful book that they put out as part of all of this called “Hamilton: The Revolution,” and that was my bible throughout, but especially in the early days of editing and getting to know the show. It has all the lyrics on beautifully printed photos and it has little stories from the creative team and annotations that Lin included alongside of the lyrics, saying what he was expressing in certain moments, or the genesis or intention of his ideas and it was extremely helpful to me. It was basically Cliff Notes for my entire job.

MORAN: Hamilton was already a pretty large phenomenon when I was hired, so there was a fair amount of information available to me. But, in preparation for this project, I was kind of being informed by whatever little tidbits I could grab from wherever especially anything coming from the creative team. There’s a beautiful book that they put out as part of all of this called “Hamilton: The Revolution,” and that was my bible throughout, but especially in the early days of editing and getting to know the show. It has all the lyrics on beautifully printed photos and it has little stories from the creative team and annotations that Lin included alongside of the lyrics, saying what he was expressing in certain moments, or the genesis or intention of his ideas and it was extremely helpful to me. It was basically Cliff Notes for my entire job.

There was a time when I first started, where I was sort of in the dark putting this together and that book was my North Star. Then my first point of access was, of course, Tommy Kail. He’s the master of this, so he knows every inch of it and every aspect of it. So he was my first fountain of information. So we would talk and tinker and we would put more together, put more together.

And then Andy Blankenbuehler came in and he was the keeper of a lot of the visual language — certainly, all the choreography and he would clue me into so many subtleties in the choreography and stage pictures that were very informative. But often very nuanced stuff. Still, no matter how esoteric his references, I would always kind of weigh that because I always want to show whatever his intentions were, even if I don’t get it and even if I don’t think that any of us are going to understand what it means, there’s something inherent in the art and the piece that I want to be respectful of, and so I would always err on the side of, “Let’s see that thing and let people experience it.” I don’t have to know what it is. The audience doesn’t have to know what it is, but there is something that you can absorb from that that will inform your experience watching be it in this scene or in the way you understand the whole.

I listened to Andy talk recently and he’s got so many references and so many layers to all of his choreography and all of the directions of motion and all these touches. You’ll never be able to understand all of it, but that’s why I would always show it and let that be part of the experience because he’s referencing medieval paintings and all kinds of arcana, which is amazing, and part of what is happening in his brain.

HULLFISH: Can you think of a specific thing like that where he said, “You should get that in because of the direction of their body movement” or whatever.

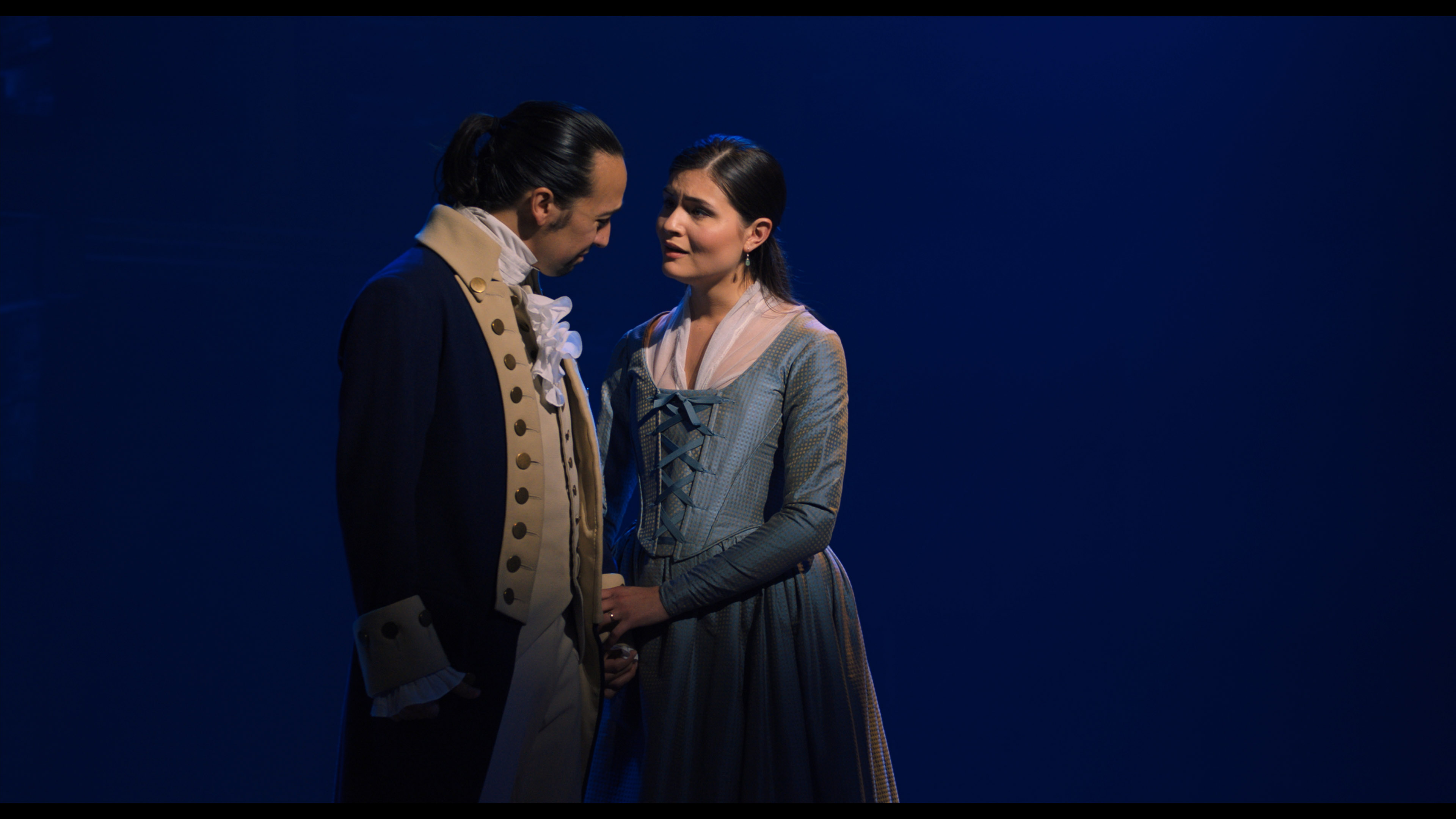

MORAN: There was one in Quiet Uptown. It’s sort of the transition point where Eliza sort of starts coming back to Alexander Hamilton. Let me step back for a second to explain that in the show, the ensemble was set up to represent America, and the American people watching this history unfold. Additionally, there’s a component where they’re kind of a jury, watching, judging Burr, judging the situation, and judging how America is unfolding.

So in Quiet Uptown, the ensemble is present in the streets of New York, they are citizens encountering Alexander Hamilton in the depths of his depression after the death of his son. There are a few couples encircling him, moving in a specific direction around the turntable and they’re in these contorted positions. There’s a moment where the women start leaning forward and the men catch them and he told me that the women are vomiting, which I didn’t realize.

It’s like they’re sickened by the sadness. This heartbreak is too much for them and they’re sickened by it. And the men pull them back and then the entire ensemble starts to rotate in the other direction. And what that meant was: when it’s rotating counterclockwise it’s a healthy position when it’s rotating clockwise. It’s an unnatural experience, and disturbing to a viewer. Maybe that’s because of us reading left to right as a culture.

But when Eliza’s about to come back and the healing is about to sort of begin, the direction starts to correct itself, and so we had to see that change. And it’s really a very nuanced subtlety but a very beautiful expression and something that had completely missed the significance of in the background and was happy to learn from Andy that that was happening.

HULLFISH: Sure. But at that moment where that lyric is spoken, you could easily have said, “Oh it’s really important for me to be on this close-up of this one character because they’re saying something important,” but then you learn, “Oh, I need to be on the wide shot because of how that speaks to the art.”.

MORAN: Exactly. And actually I was in a close-up at that moment originally because it is this very wrought moment for Hamilton and Eliza. A very transitional moment for those characters, and so, as a filmmaker I think my instinct was to be intimate with them, but I think there’s a larger expression happening at all times in the show and I certainly wanted to always be respectful of that and Tommy would be a little bit bolder, “No one’s going to get that. We’ll push through. Forget it.”

He would give me permission sometimes to skip those, but I would always try and sort of capture as much of what was happening on the stage as possible because I feel like it’s all significant.

HULLFISH: It reminds me of the thing I’ve talked to multiple editors about when you’re in the mix, the sound designers want the sounds played as loud as possible, and the composer wants the music to be played as loud as possible, the director probably wants the dialogue as loud as possible. And you’re like, “Now what do I do?”

This is the same thing, right? The actors would probably want you to be on their close-up and the choreographer’s always wanting the widest shot possible.

MORAN: Yeah yeah yeah.

HULLFISH: It’s a hard, hard thing to try to balance, I’m sure.

MORAN: Definitely. With the balance of close-ups, we were always trying to not spoil that. To make those close-up moments have more impact. And we were not trying to hide the fact that this was on the stage.

This was a bit of a hybrid piece. This was somewhere between a dramatic narrative film, a documentary capturing of these nights on this stage, and this other language of choreography and almost music video.

We’re sort of synthesizing all of these things to create an expression of what was beautiful about what was happening in that play on those nights and on that stage. That was the specific assignment. And keeping that emotional and engaging was definitely our primary concern — but also being respectful to all those other facets.

HULLFISH: You mentioned the nights. Can you explain what kind of source material you had? What was shot?

MORAN: The first show they shot was the Sunday matinee in its entirety with a full audience. That was just the play as it would normally be. They positioned cameras in the audience, mounted one above the stage, one above the surround, which is the upper section of the stage surrounding and above the main stage and one camera pointing out at the audience from the back of the stage.

This set up was conceived by Tommy and Declan Quinn, the Director of Photography. Declan and his incredible crew are so skilled at capturing these things. He has done a few live shows like this before and each has a specific aesthetic that matches the show perfectly. And what he was able to achieve in this setting constantly took my breath away. Just with the subtlety of camera movement and how he and his crew were able to push in at the right time, maintain focus. I mean, it’s incredible.

But it was the Richard Rodgers Theater on a Sunday matinee.

HULLFISH: How many cameras?

MORAN: It was 10 cameras. There about 7, 8 really, active positions. Then we had kind of those specialty ones like that overhead occasionally and the behind the stage. We used those very sparsely for very specific moments.

There were about seven primary positions that we were constantly cycling through from two performances: Sunday and Tuesday. And then in the interim — after Sunday we wrapped, the show ended and then everyone took lunch and came back in — and they shot three or four specialty numbers which is where we got the Steadicam footage from and some of the more nuanced close-ups and tracking shots. They shot about 13 numbers that way.

A few on Sunday night and then Monday, which is a dark day for Broadway, so they brought the cast back: “Sorry guys, No days off for you this week!” We did eight more numbers on Monday, being able to sort of really stop down and focus on those larger numbers.

They still ran the numbers in their entirety, though. Every expression of this was trying to achieve the live experience and the continuity of what that storytelling is and how that works — for performers for the show.

So that was Monday and then Tuesday we did a couple more numbers before the show and they did the show that night, again with an audience and using manny of the angles from the first night but usually a little tighter and adjusting others. And that’s our material.

And none of these shows were ever stopped or anything like that. This was the show.

HULLFISH: So a Sunday performance with 10 cameras or so, and a Tuesday performance with 10 cameras, and then a few numbers without an audiences using specialty cameras like Steadicams?

MORAN: Yeah. We did 13 specialty numbers — what we called them — three to five takes, usually. If we had a Steadicam present for one of those numbers they would probably do two takes with the Steadi and two or three without. The ones without might have a crane. Tommy would bring that in for different moments. “Non-stop” has some nice crane work and the “Schuyler sisters” ends with a little bit of crane. So the crane was a part of when they weren’t doing the Steadicam stuff.

HULLFISH: Did you ever stretch or compress time or was it completely real time?

MORAN: We maybe nipped out a couple of frames. All of “the cabinet,” as they call them, which is Tommy, Lin, Andy, Alex. They are all in general the sharpest people and most artistic people I’ve ever met, but also just at their craft, it’s incredible how honed in they are.

Alex would ask, “Can we take two frames out of the space between those songs? I know it wants to be faster.” I’d say, “Two frames, huh?” He says, “Yeah. Two frames.” And I’d nip it out and he’d say, “That’s it.” And that was it. Amazing!

The show is the show. To me, they did a lot of the content-based editing you would normally do on a film before I even came in, because they workshopped the show for years. It had been in workshops, off-Broadway, they’d been doing previews and that’s them honing the show and — in effect — editing the show. It’s the same way we would normally go in for content and try and expand or build a moment, or refine the structure. So that was the show, I was just trying to find space inside of that construct to give moments breath of their own — a visual space.

And I would steal that, usually by trying to come in a little early on somebody’s line and hanging with them for a moment after it finished, to kind of watch it rest. Or in some cases really brief stuff like in “Satisfied” I would just steal every moment of Angelica I could find because Rene is just so expressive and that’s such an emotional song. But also, the emotion is sort of wedged into and between thousand-mile-an-hour lyric delivery and stage activity, which is incredible.

I would just try and get with her every time she was giving a little bit of that emotion and I there are a few really beautiful, subtle moments where she’s sort of off-action, she’s just introduced her sister to Alexander Hamilton, her sister is overjoyed and he’s found a Schuyler sister to bed down with… We had already sort of seen a version of this moment once, in “Helpless.” And so this was an opportunity to kind of re-frame and watch that experience on Angelica’s face.

Those are really quick pop-ins, but because Rene’s so expressive, you see that emotion and it flies right at you, just like the song is flying at you.

So it would generally be through extending shots — holding on shots — a little longer and just using rhythm of the show to get us in and get us out. And that’s the feeling that you’re using to help you into and out of those moments.

HULLFISH: Since we talked a little bit about camera positions and some of the special camera stuff that came in on those days that were kind of off the performances that were not full. Talk to me about using those cameras especially the Steadicam coming in for the close-ups.

I think it should be obvious to most people that have the visual sense to know: that camera’s got to be on the stage. Or the overhead camera is the other one. Those are the two that I’m most interested in.

MORAN: The overhead cameras ran every time we shot a number, so they were running during all the specialty numbers, as well as for the performances in front of an audience.

It was just a matter of how do you deploy those? Because it’s a pretty disorienting angle, and you don’t want to take people too far out of the thing – one of my primary self-directives was maintaining orientation, you don’t want to get lost on the stage. Where are these characters on the stage? Where are they in relation to the other characters? When you go to extreme angles — and even the Steadicam to a degree — you kind of lose that perspective a little bit. Things kind of move and you can get lost. And I never wanted the audience searching for where they were on the stage because that would mean they’re not paying attention to the storytelling which is what’s important here.

And so where we use those overheads were places like “The Rewind,” where that IS a disorienting experience. It was also an opportunity to really highlight one of Howell Binkley’s amazing lighting. He has this incredible lighting cue which converges all the lights around Angelica. To me, seeing that cue just shocks me and tells me, we’re out of time and space, and just makes you feel like, “what’s happening?”

So you get to highlight these sexy things that most people will never see. In the mezzanine maybe you can kind of see that, but you don’t really get that perspective. And so we’re rewinding. We’re out of time. We can be disorienting here! We can take some liberties.

Then we used it again in the “Reynold’s Pamphlet” later on, with everyone dancing around Hamilton. They throw up the pamphlets into the camera and that’s kind of a crazy moment. Andy describes that piece as his “Tim Burton piece” and it’s definitely wild. It’s just bizarre what’s happening and crazy angles and staging. So, we had permission again to kind of get into a crazy perspective.

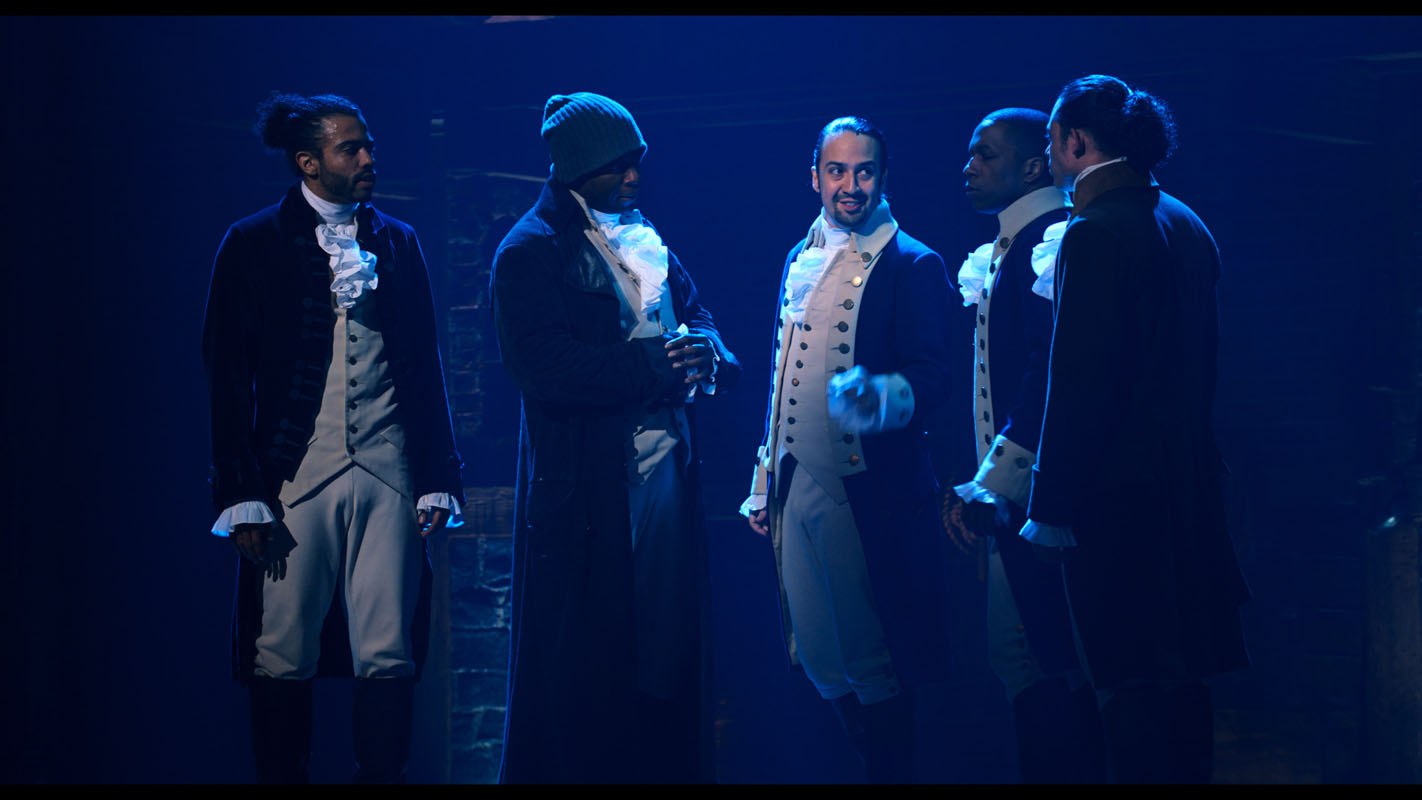

And then we used it again in “Non-stop.” At the beginning of “Non-stop,” this is the formation of America we are looking at, and the overhead kind of told the story of these characters coming into this circle and setting down chairs to build the first courts of America. It gave a sense of the construction of the country and the foundations on which it was being laid. So it felt appropriate there, watching the pieces assemble.

With the Steadicam, we tried to be very careful because it can also be disorienting. It’s challenging to get into and out of that, especially cutting from your standard coverage of the show — going from a very wide perspective to a very tight perspective, it is very dramatic but it can be jarring, so I would try and use some sort of motion to kind of cross those lines.

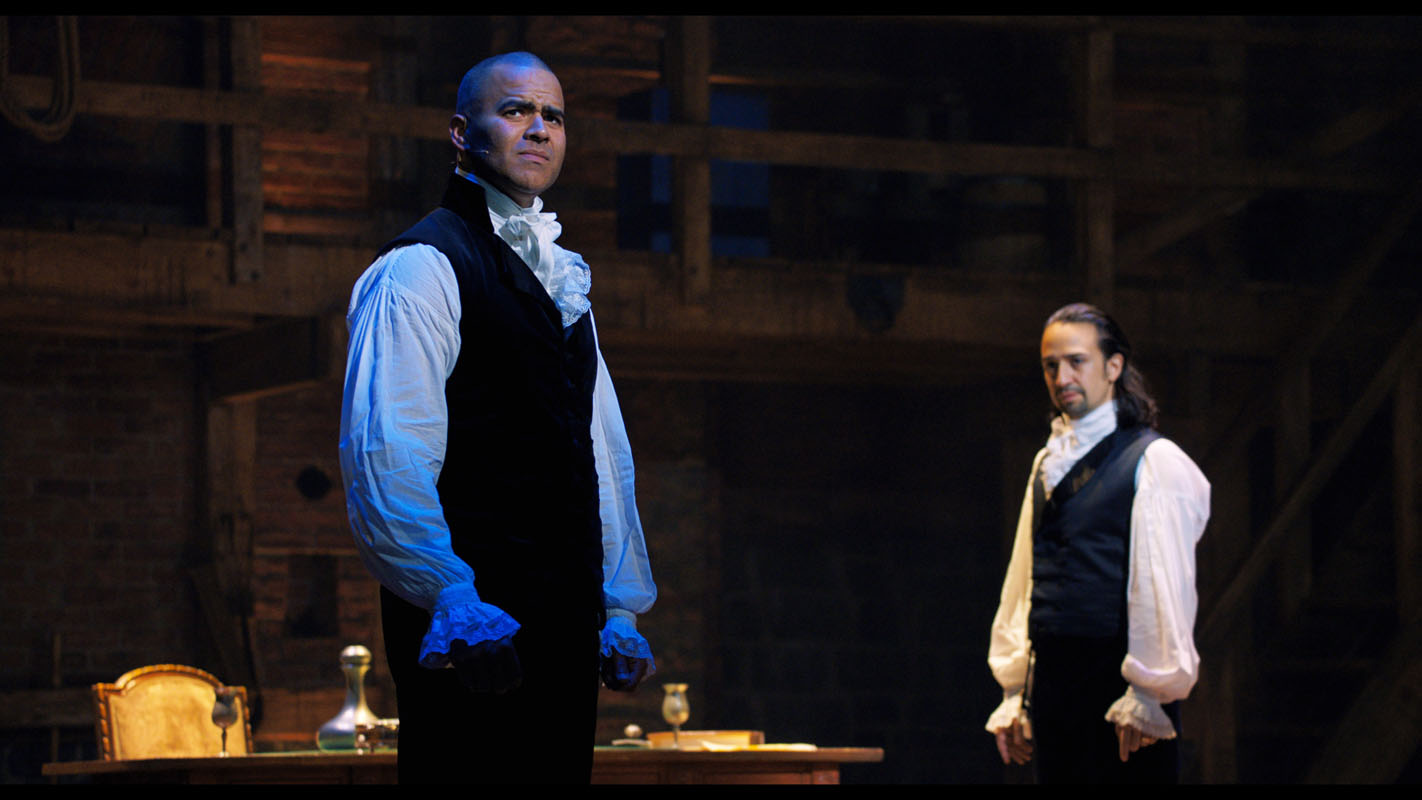

The first time — with Hamilton’s entrance — there were some ensemble dancers who crossed in front of him and that motion continued from the wide into that presentation and sort of made it feel a little bit more fluid, but obviously, you also want to call attention to the fact that this is our central character — this is Alexander Hamilton – You feel a little emboldened to go into those kinds of shots and you want to highlight those moments. The only other person we highlighted in that first number with the Steadicam was Burr. We come to him at the end after, “damn fool who shot him” because we wanted to show: “This is the other guy.” And this helps set the premise of the relationship that will unfurl throughout the film.

Again, we came to it in “Schuyler Sisters” as they’re entering — which is such a gorgeous, colorful, exuberant scene. But, still, definitely, you’re playing with: “where do we come into this?” I let them enter before going to the Steadicam, because there was a lot of stage activity that we wanted to track before their entrance, and then once they enter you come to them and it’s, “These are the girls. They’re more of our favorite people who we will be watching for the next two hours, so everyone gets psyched.”

They’re so expressive and beautiful in that. It’s one of those moments where you can let it open up into that full-color spectacle and it’s really exciting.

And honestly, you could watch those Steadicam takes all on their own. There was a moment in “Alexander Hamilton” before we opened up on Hamilton where the Steadicam actually followed Eliza onto the stage and there was this gorgeous light that came in and it was just a perspective no one will ever see. Tommy and I just ogled over that! “God what can we do with this?” But it just wasn’t the story. It wasn’t telling us anything about the story. It was just a beautiful distraction and you want to eliminate beautiful distractions, unfortunately.

HULLFISH: That’s an interesting idea. That’s “killing your babies,” right?

MORAN: Yeah exactly.

HULLFISH: That’s a hard thing to do. That’s a very hard thing to do, especially if the director was saying, “We HAVE to have that shot!” Luckily, you weren’t that put in that position but….

MORAN: We both knew that would never live, but we both were thinking, “God! Can it be in the trailer? Like, where can this go?”

Ultimately it just doesn’t really tell you anything but there is something so exciting about being on that stage and being on those boards with those performers.

Honestly, if we had done too much of that it would have spoiled the thing. You use it only for the targeted moments where it’s really important, otherwise the milk goes bad and nobody cares anymore.

HULLFISH: What’s the deal with multi-cam and not using multi-cam? I’m assuming that you were cutting multi-cam all the time?

MORAN: Absolutely. I relied on multi-cam with this. That’s not to say that I didn’t watch it as individual cameras.

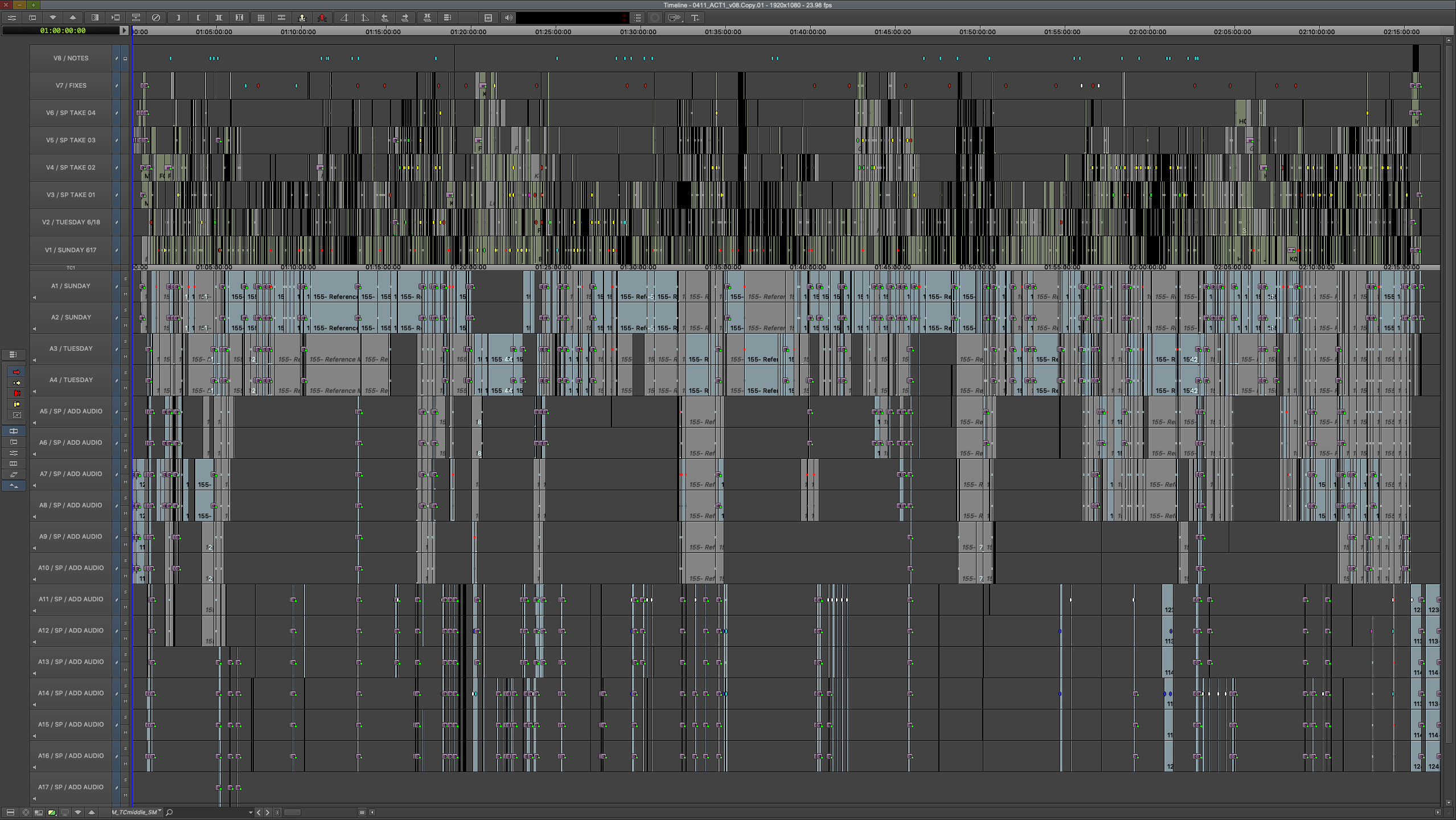

Junior Nunez — my assistant — would go through and multi-cam all the performances — a gargantuan task — I didn’t even really get under the hood and ask him how he was doing that. He’d just keep feeding me these extremely impressive multi-cam sequences that are like an hour long.

We would take those and sort of divide them up scene-by-scene. We would divide those up and create little “scene stacks.” I would have him stack each multi-cam take. There were always at least two multi-cam groups of ten cameras in the timeline, and then on top of that any specialty stuff.

Sunday’s multi-cam was video track one. Tuesday was video track two. Take one of a specialty would be video 3 and on, and on, and on. Then I would go through and I would break them down add edits and King the different takes up, because also there are sync drifts between the different performances. These are performers, very well-rehearsed performers, but they are doing it live and though some of the songs — at least certain parts of the songs — are to a click track, so they were pretty steady every night, but there are entire patches where the vocalists are in an emotional moment and you let them dictate the tempo. So I had to find ways of lightning up the parts that I could, to make examining the options more of a streamlined process.

I would go through the ten cameras and isolate each one and watch through. Some camera positions were easier to sort of scrub through because they were from weird canted angles, like above the balcony that I knew I would only use for specific things so I could hunt through and find, “What does that moment look like there? No. No. No.”

But for the featured cameras from the front of house I would scrutinize each camera and go through one at a time and mark where I thought there were moments that were appealing and significant and that gave me some kind of emotional response or heightened perspective.

I would do that for each take. Ten options on the first take. 10 options on the second. Probably five or six on the first take of specialty. Five or six on the second. Then I would just weigh which ones were telling the story for me at that moment.

Then Tommy would come in and we’d go back through and he’d ask, “What’s the H camera doing right here?” or “What’s G doing over here?” We went through and got to know our cameras. Got to know where our positions were — and you could kind of get a feel for where things were gonna be after a while.

I love going through footage like that because, 1) you don’t know what you’re gonna miss if you don’t go every take in its entirety. When I’m working on narrative stuff I watch pre-rolls and after-cut because you never know. You might get a really natural moment from a performer nervously thinking about their lines or something.

But also it gives you intimacy and it gives you a familiarity — especially with this dense piece of lyrical content — i’m listening and experiencing the play 20 times before I’m making editorial decisions. So I know the scene. That’s really helpful.

HULLFISH: And are you using that thing that your assistant created for you as a source? Or are you duping it and editing THAT?

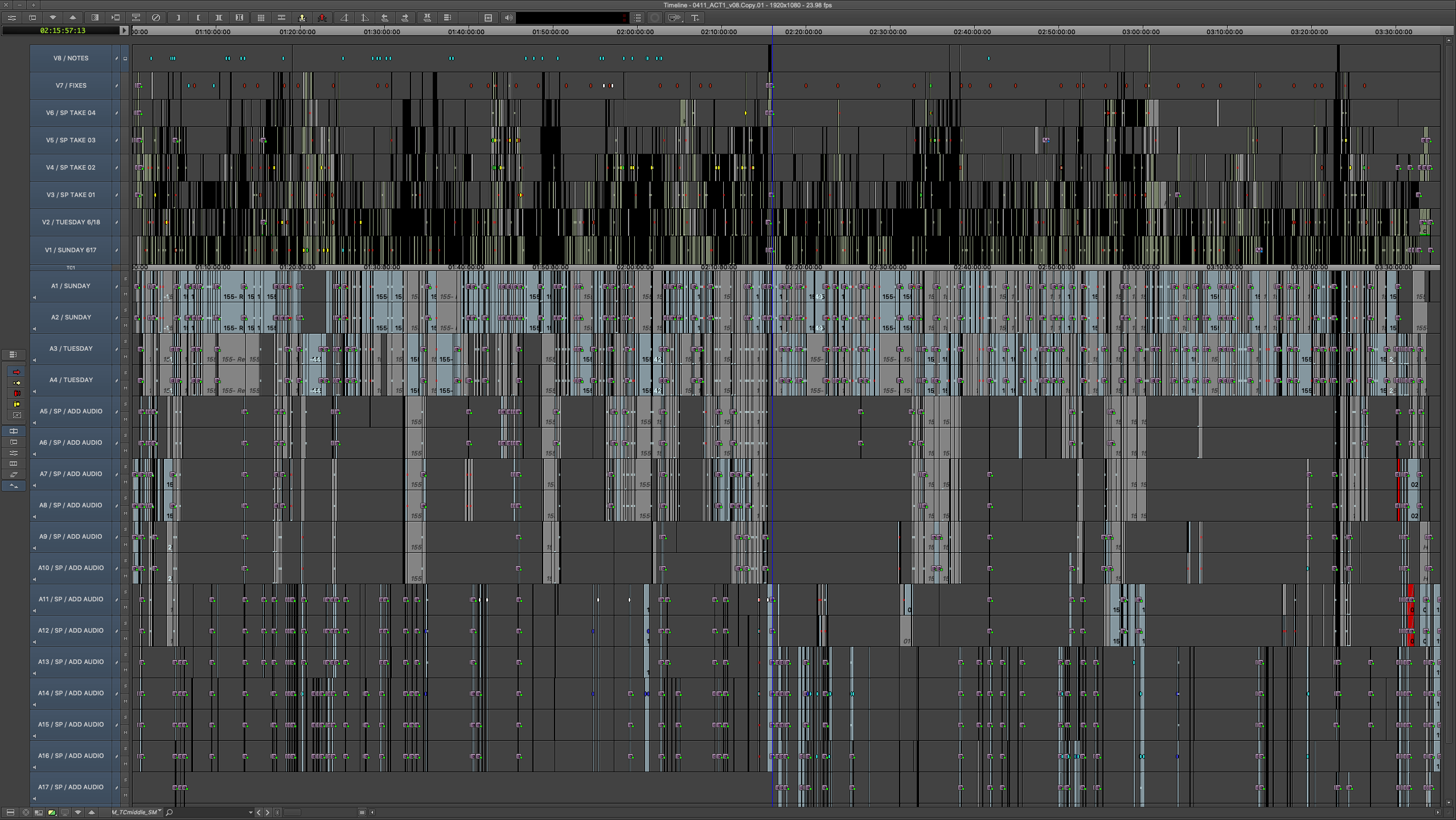

MORAN: I thought I would be working with that in my source monitor, but it’s challenging because you don’t get the same playback options when it’s in your source monitor. So, I’d dupe the sequences and cut right in the timeline mostly. As a result I have very intense timelines. I’ll take a screenshot of my timelines for you but they look like frickin player piano rolls 10 high video tracks of a thousand cuts and it looks like madness. You might think I’m a crazy person after you see them.

This is such dense content. There was never a point where I knew we wouldn’t go back and reexamine things and in fact, we did. Our fine-cut essentially was from October 2016 — which was just a few months after they shot in June — so it was October until about April that we cut our first fine cut.

Then it went into a vault for a little while until it was sold to Disney. Disney gave us the opportunity to go back in and look at the thing again and re-examine some of our choices. I went back to those stacks, believe me! I was very thankful for having those stacks of options because everything was just waiting for us to scratch and poke at when we got back to the cut.

It’s a unique and really wonderful luxury to be able to go back to a piece after you’ve stepped away from it for a while because you kind of forget why you made certain choices, so you watch it as a viewer a little bit and you say, “why that?” I mean you do that anyway as an editor, but you can always have the active debate in your head of what you want vs. what you think is possible. Not having those original rationalizations so sharp in your mind is liberating.

Tommy and I sat down in January of this year in a beautiful theater at Harbor Pictures and watched the thing for the first time in a while and compiled our lists of things. Some of them are nit-picky but a lot of it was about: What have we learned over the years, being collaborators working on Fosse/Verdon together? What have we learned as individuals? As storytellers? And what can we push? What do we want to push further? What feels gratuitous? What isn’t working? A little bit of it was, when can we be more intimate? When can we get closer?

There were a couple of moments where we asked, “Can we push this emotion a little bit further and be a little bit more intimate here?” So we compiled our lists and wrote that up. Then, I went in for two weeks in early March and I started cutting those things and trying things.

We knew we had a working film. It was really good already. We were really happy with it. So it was incredible to be able to do that and I’m very thankful for that luxury because every project you walk away from there’s a feeling that it’s been taken from your hands at some point and you think: “If I just have one more week! Two more days! If I could just make one change!” You’re pleading with the gods but usually, it’s not to be and this was a very unique and lovely exception to that.

HULLFISH: The number of people that I’ve interviewed who got a chance to do that are very few. There are only three or four or five people where an actor got injured or some legal thing and you get to revisit it and every single person said that made it. That ability changed it.

MORAN: And we did know that we were gonna go back into it. When we put the fine cutaway, we didn’t really have an opening for the show. It kind of just faded in. We had the titles and stuff, but even as we were doing the mix process — which was an incredible process with Alex and Nevin Steinberg, who’s the sound designer for the show, and Tony Volante and his team at Harbor — all of them are incredible artists.

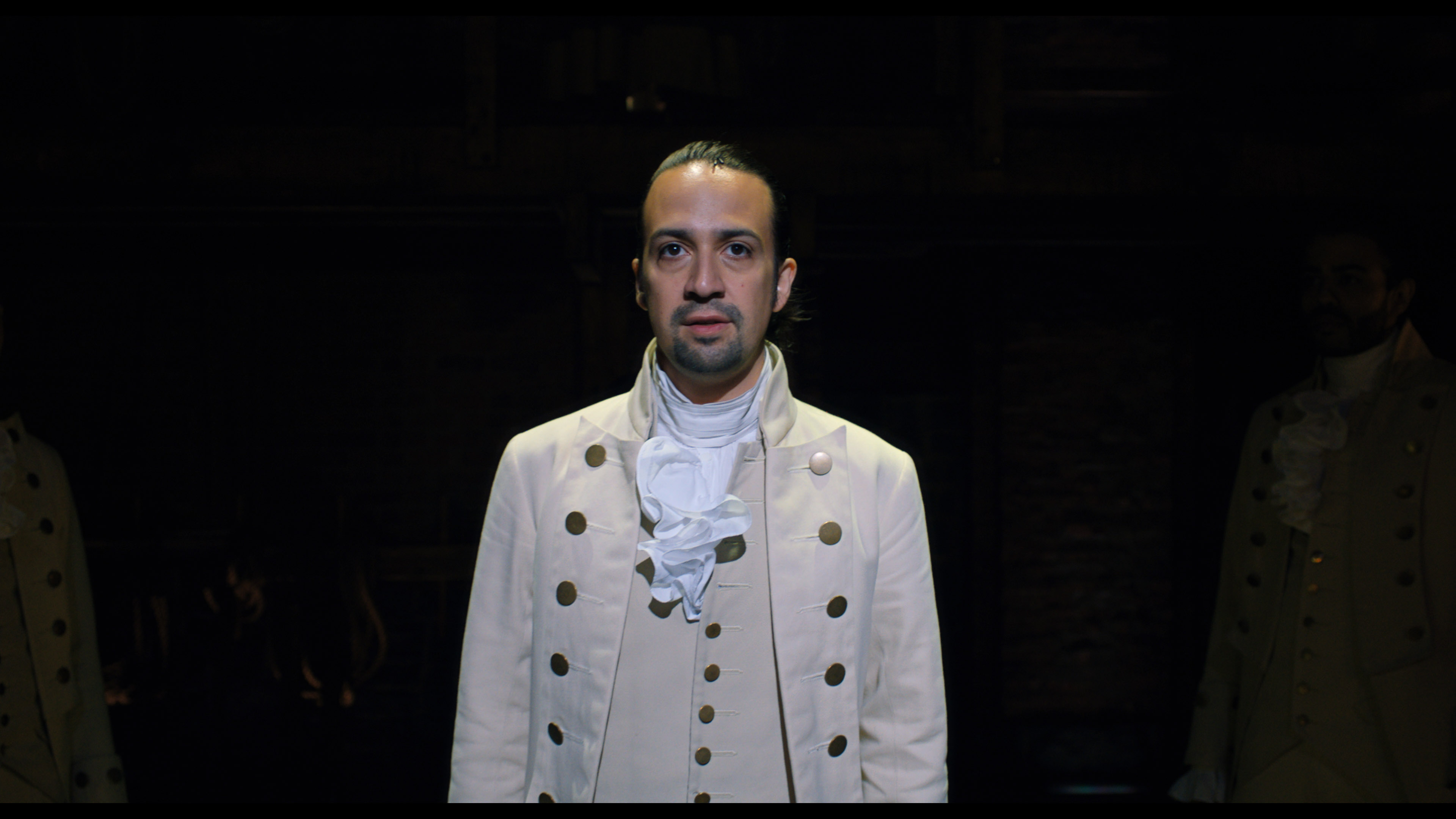

But when we went in there, every time we would sort of watch it down — and in the mix the film is supposed to be locked — so you’re tracking how your storytelling is happening in audio and if all of the sound is present, how the balance is, where you want to locate things — we had a surround mix so where are we locating sounds? But, the other part of me was watching the opening thinking “I don’t feel settled in this yet.” What IS this thing, because this isn’t a standard type of movie, so that raises questions in the audience’s mind. And on top of that, the movie experience differs from the stage experience. In the theater you go to the theater with an energy and an enthusiasm and you’re there with people and you’re sitting down and the lights blink a couple of times and you have an anticipation and preparation that the show’s about to start. And each show is different, but the ride to get there prepares you for what comes next – for Hamilton, the lights dim and a light comes out of the stage right wing and shines across the stage and then Burr rockets out and starts the show and it doesn’t slow down from there.

In the cinema that’s a lot. Originally, we didn’t have the king announcement in there. He does an announcement at the beginning to silence your phones. We talked a lot about that. Will we have the king? In the script, the king is the first thing. The first lines in the script are the “Welcome to my show” bit. It gets a laugh, and it sets a mood and it does all of these great things and so that was one of those things that really helped the problem of getting into the show. We get to live in the theater for a little bit longer before the show starts, we hear the King’s voice, we have some humor it’s fun!

Then, we also built sound design under the Disney logo! Somehow, it really comes to life when you put on the company logo! That’s a movie! When we got that, that was a real opportunity to make it even more exciting and putting that sound design was so much fun to play with and such a great way to pay homage to the character of the show and give a little something fun to the fans as a little treat right off the bat.

The guys at Disney were so generous. They said, “Do whatever you want! Take some chances!” And that kind of gave it a little bit of life and energy that I think propels you into the beginning of the show and lets you watch the thing with an energy that was kind of lacking in the uncertainty of just fading in on the thing.

But that didn’t exist at first, so we knew we were coming back into it for that. There were no credits at the end. So we knew we had more work to do, but actually getting back in there to tinker a little bit under the hood was really wonderful.

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about how you got involved with this director and got this project.

MORAN: Well, it actually goes way back. I first really met all of these guys back when they were doing In the Heights. I was working with a producer named Andrew Fried and we were working on a documentary about In the Heights, called “In The Heights: Chasing Broadway Dreams.”

He’s actually got a documentary coming out this month — I think July 17th or 18th about Freestyle Love Supreme, the other side project that Lin and Tommy, Chris Jackson and Daveed Diggs are all a part of. So, he’d been kind of following Freestyle Love Supreme for a couple of years before we did the In the Heights thing and he was trying to figure out if that was a TV show or if it was like webisodes. That never really evolved into anything at that point but in the meantime, they kept saying, “Lin’s not here. He’s off working on his musical, In the Heights.” Then, all of a sudden In the Heights was going to go to Broadway, so Andrew asked, “Can we cover this? I want to follow you guys and watch this process.”

They were generous — as they always are — back then and generous now. Generous enough to let him in there with cameras and we got a really great doc out of it. And for the doc, we did a couple of the numbers from in the Heights as well, so I think Tommy saw what we could do with live stage plays and turning them into pieces that work on the big screen or small screen as well as in the theater. From that, we forged a relationship and he’d come in and watch cuts with us, give notes and chop it up and joke around.

We kind of bumped around each other in the intervening years and when it came time to do this, he called me up to the 42nd Street rehearsal space to discuss the film. Tommy took me into a side room and talked me through this and he said right then, “It probably won’t come out for five years.” And I thought, “No way!” But I didn’t care. I’d do it no matter what. I thought, “There’s no way I’ll take five years.” But, if we hadn’t pushed the release up to this year on the third, it would have come out October 2021 and that would’ve been almost exactly five years from when we started.

HULLFISH: How do you break the scenes or your workload?

MORAN: I would break it down by song usually. Some of the numbers do kind of run together like “Helpless” into “Satisfied.” In fact, the first third of the show runs pretty much back to back to back.

I would kind of finish one and start tinkering with the next one. Find that transition moment. What was that going to be? Start playing with those kinds of things and it would start building in front of me.

But I had all of them as separate scenes with those syncs and things that I was talking about, where I would break those down and kind of evaluate it like that. But when it came to edit, I would start assembling chunks right away. As soon as I was through a cut of a scene, I would want to see, “how does this tack onto the next scene?”

I generally took it in chronological order and built and built and built. Except, I think I started working on “Room Where It Happened” earlier because I knew that was a big one and we had a ton of coverage for that and I just didn’t want it hanging over my head, honestly.

There was a lot of work between when I started and when I was going to get to “Room Where It Happens” but I wanted to give that everything and have a version. And then when I get back to it I’ll work on it again. I just wanted to get through a big chunk of it, knowing what I like in that and then circle back later.

But, I took it pretty much one song at a time and would build those transitions as they presented themselves. Like with the Steadicam stuff, I was always looking for some shot that would sort of take us from the end into the next moment and sort of serve as a little bit of glue to make it all just feel connected and not disjointed at all.

Unlike when you’re building scenes for a normal scripted movie or TV show, it was all continuous actually. Actually separating it was harder than keeping it together in a way.

HULLFISH: The other thing is that you have all the material when you start.

MORAN: Yeah. We’re not taking it out of continuity or anything like that, we’re tackling it from the beginning to the end. And it’s the way they wrote the play, so it felt like somehow that’s what Hamilton wants is to just be started and moved through to the end. That’s the experience.

HULLFISH: With the exception — as you said — of jumping into “The Room Where it Happened.” I’m really fascinated by that because I’ve done that too, where I don’t feel ready to tackle a scene right now. Or I want to jump to the big scene because I don’t want it looming over me. There are personal psychological reasons for the order you attack things.

MORAN: You’ve got to kind of follow your mojo a little bit. What are you up for? If there’s something that’s exciting me I’ll tackle it right away just because the scent is in the air and I want to just keep pursuing it. I don’t want to let that go away. I want the fire for the ideas to kind of come through right away.

Sometimes, something gets in my head, like a feeling, or a song — like I was listening to the cast recording on frickin repeat, and so if there was a song or a moment that I thought, “What are we going to do there?” I would dip in and check it out for sure. But in general, it was built in a linear fashion.

A friend of mine, Meredith Coffers who is a great producer and a very organized mind — much more organized than mine — early on she asked me, “How are you tackling this thing?” I just said, “I’m just cutting.” She said, “So when’s your first rough cut due?” I said, “December or something like that.” She said, “How are you going to get through all this stuff by then? What song are you on?” And I was like, “I don’t know. I’m just working on it.” This didn’t work for her at all… She went away and made a list of all of the songs and said, “OK, you need to be on ‘Cabinet Battle 1’ by November 10th, ‘Room Where it Happens’ on November 16th, etc…”. That really, really helped.

Then Tommy came in one day and wanted to start working on some song we had already made a pass on and I remember starting to freak out about the schedule, like “But we need to be on “Room” by the 14th!! He just calmly said, “Jonah, don’t worry about the schedule, it’s our show and we want to do it right.” So I went back to just worrying about normal stuff, like, how do I make HAMILTON — the biggest thing in the world — something that people can relate to and enjoy in a cinematic space rather than in a live theatrical space?

HULLFISH: How do you do collaborate with the director? How much were you on your own cutting a scene and then how were you collaborating with the director? Any producers? You mentioned the choreographer. Who are the other people in the room where it happened?

MORAN: Those people were all in the room where it happened at various times. The way it generally works — and the way it worked here — is that you kind of go away as an editor and you work the scene. You create what’s generally known as an edit cut.

When you’re working in longer form, like television or movies, you generally do a full pass as an editor and the director often checks in. With this, we were working more in chunks. Based on Tommy’s availability, he would check in usually — in the beginning — maybe once a week. Whatever frequency he was available essentially.

Anytime he would want to come by I would say, “Please come by! Yes yes yes yes!” Because every time he was in the room everything got better and it just gives you clarity to bounce ideas off of somebody like Tommy Kail. I’ve heard him call himself a coach and I think he definitely is that. He knows how to bring stuff out of you and make you believe in yourself in ways that you might not otherwise. But he’s also the smartest guy I know and able to bring so many ideas and guide you and pull you back and show you things and tell you things about his show that you just might have missed.

So, every opportunity I had to work with him, I jumped at. But when I was just in the room alone, we actually — because of security reasons — Junior, my assistant had to be in the room with me. So our media never left the room. We locked the door. Left our cell phones out at the front desk of the facility we were working at. We were sequestered in this room together.

So I would just go through a scene and kind of watch through with him and we learned a lot just by kind of sitting back and watching what worked and what didn’t work. A lot of the initial work — just going through those timelines the way we were doing — it was a little bit more cutty and trying to get too much in. It largely became an exercise in sort of stripping away what you don’t need and getting to the meat of what really is important in telling the story. Letting the eye settle on the beautiful things that are happening in front of you — as you do with any project – but especially with this because we had so many options.

What starts to happen at the beginning is a lot of those options get in there and then you have to lift them back out. You don’t need all of those.

I remember sitting with Junior on “Wait for It” which is such a beautiful spare number anyway. It’s just perfectly simple. But you want to be in close with Burr, because Leslie’s so emotional and perfect in that number, but there were just too many cuts. It’s just distracting me. I just want to experience this amazing moment. So it was just putting in and taking out — and mostly just taking out. Taking things out and finding what it was. Each scene has a character, you need to find the best way of expressing that character.

Once Tommy and I had a cut that we feeling good about, then Alex, who Orchestrated and arranged the entire show, came in. Alex was very generous and lovely that first time but I know in the back his head he was probably thinking, “I can’t wait to get to the mix.”

We had a certain amount of control over the mix in the off-line environment, but not a lot. I was mostly working from just a stereo mix-down of the performances. We had all the mics — over 100 mics — like 10 mics alone for just drums plus the whole band, audience mics, mics at the foot of the stage, every performer obviously. So much sound to deal with.

That was an unwieldy amount of stuff to actually have in the timeline, so if we needed to hear something specific, I’d ask Junior to pull the iso mic if we needed to hear a lyric a little better.

HULLFISH: So when you were cutting picture, you were basically dealing with just a live stereo mix.

MORAN: Largely. I mean there were areas where there was much more — creating better balance with the ensemble and things like that — but largely it was just that mix. Mostly it was finding audience mics because that mix was very stage-centric and so we were trying to find the balance of audience to the stage work. We wanted to feel audience. But it wasn’t like a comedy show where there are guys laughing in the audience.

HULLFISH: One of the moments for the audience is when the King singing and he says “I’m so blue” and he stomps his foot and the lights go blue and the audience laughs.

MORAN: And when the king enters we did the back-of-the-house camera, and part of that is that the king’s performance is an interaction with the audience. He’s talking to America there and the audience is America in this case. He’s basically lambasting them for being such cocky little pricks and they’re loving it — laughing, eating it up — but that’s the interaction there.

Especially in the King numbers, the audience is a huge part of the experience. They’re much more present in a way in that. It’s also a much more raucous sort of interaction there and it’s just him and them, and so you really feel it. There are audience reactions during “My Shot” that you can’t hear because the entire ensemble is singing and doing things that are way more important than hearing whatever the audience is doing. When it’s just the King and just the audience then it’s more of a conversation.

HULLFISH: So on a scene like that you might ask, “Hey, Junior, can you pull in some audience tracks?”.

MORAN: Definitely. That was an important part of those scenes and making sure those takes match up and that the energy is just right. We never boosted anything or pulled in canned audience or anything. Maybe we’d look at what the laugh was from the first night, what the laugh was from the second night, but we never pulled in anything fake. It was all real.

HULLFISH: Then the choreographer had to come in at some point.

MORAN: Andy came in and that was like another masterclass in the show and where we needed to be. He was often looking at how some of the significant stage pictures would translate to the cinematic space. And he could tell you details in certain formations and poses that were incredible. Sometimes he’d comment that I was dead on like in “Room Where It Happens,” there is a certain moment where the choreography is lining up forming a picture of strength and unity behind Burr, as he realizes his ambitions. We were coming around to a square on front-of-the-stage picture – I chose this because what he was doing on stage came through best in this shot for me, but he was like “I love that you knew that this was the shot where Burr won the sympathy and support of the ensemble and came to this shot when he finally built the room.” I definitely didn’t have that articulated in my head, but as soon as he said it, I realized that his intention in moments like that had definitely been guiding me, whether I fully understood it or not. It’s a big part of what makes this musical so beloved. There is just so much detail.

There’s a moment in “Your Obedient Servant” where Hamilton and Burr’s conflict is escalating and escalating and the ensemble is doing this “lean thing” where they’re sort of leaning in towards the action. I had been a little tighter and Andy said, “No. We need to see that lean.” The lean definitely gives you this focus, this attention, and the whole country is drawn in. I think it enhances the tension more than anything. This is all hanging on this battle right here. There’s just so much detail in the way he puts together his choreography and his stage pictures that it was really a wonderful education in the play.

HULLFISH: The interesting thing you pointed out — which I think is great — is that so many of your choices were correct because you’re both telling stories. You’re seeing it as a storyteller. He’s seeing of a storyteller. So some of those choices should have intersected. You would think.

MORAN: Yeah. In fact, after Andy left, Tommy said, “That’s the fewest notes I’ve ever heard Andy give.” I felt very honored, very lucky and very happy to hear that.

But, the insights of each member of the cabinet were invaluable and welcome. So anytime they had a note I wanted to figure out a way to incorporate and address and happily did so.

HULLFISH: So you talked about the Hamilton: The Revolution book (which I just purchased, by the way) that had a lot of notes in it. Was there any other studying that you did?

MORAN: The musical was the study. I don’t think I took a subway or walked out of my house a single day, from the hour after I saw the show for the first time until we finished cutting the first fine cut, where Hamilton wasn’t playing on my phone. I listened to that thing on repeat from August 5th through late April.

Then when we put it away I sort of cleansed myself by listening to “In the Heights” on loop for a while. Coincidentally, I sort of trickled back into Hamilton a few months ago, right before we started the edit up again. I was finally excited to re-engage it and then before I knew it, we were back in the edit room.

That was my study: listening, watching the show. I was fortunate enough to see the show five times in New York just to study it. The entry point was watching and studying the show — the first time especially — because things that emotionally hit you there, are the things you know you want to convey emotionally to an audience ultimately.

HULLFISH: So did you take notes at their first viewing?

MORAN: No I didn’t. Mostly because I felt it would be incredibly obnoxious sitting next to people who paid like ten thousand dollars for their seats and I’m just sitting there with like a pen and pad just like scribbling away.

HULLFISH: I was thinking about doing it on your iPad.

MORAN: Honestly, that’s how I would have done it. No. I was discreet enough not to take notes then, but I was like mentally logging the experience. That’s part of why — as I left the theater — I was downloading the cast recording so I could start cycling through the songs and remembering what I remembered from them.

HULLFISH: How much of them wanting you to be an editor on this do you think is because they knew the way that you collaborated instead of the way that you edited?

MORAN: That’s a very interesting question. I think that’s probably a significant part of it actually. I think that’s how Tommy approaches everything is through the people not through the work, and knowing the passion that people will bring to it. I think that’s probably why he was interested in me in the first place.

I think he’d seen versions of me doing this kind of work in “In the Heights” stuff. I think it was just sitting and having a conversation and talking through what this process would be and what this play wanted to be. What this movie wanted to be.

I think you’re exactly right. I think that is a large part of how he deals with everybody. I’ve seen it in the way he talks to his collaborators in the Cabinet. I’ve seen it with the way he talked to Andrew Fried — the producer I was speaking about earlier — I think Tommy, in particular, is somebody who just values people’s spirit and their emotional contributions. I’m certainly happy to give anything I can to him and in the effort to help him make a piece like this.

HULLFISH: “In the Heights” was supposed to be out this summer, right? The feature film?

MORAN: Yes. I think they’ve cut it and finished it, but there are some things going on right now, and so I think they’re delaying that and trying to find a time. And I think they want to make sure that it gets seen in a theater. So I think they’re delaying that until that can happen. I think they’ve actually officially delayed it till next summer.

HULLFISH: It seems like a summer movie. The kind of movie that you want to see in the summer.

MORAN: It’s about hot days in Washington Heights in New York City during the summer: breaking open fire hydrants and setting off fireworks for the 4th of July. Those are central pieces in the play and I’m sure in the movie, so yeah, it’s a summer movie.

I keep getting sort of sidetracked in the journey of presenting to the collaborators and the Cabinet members.

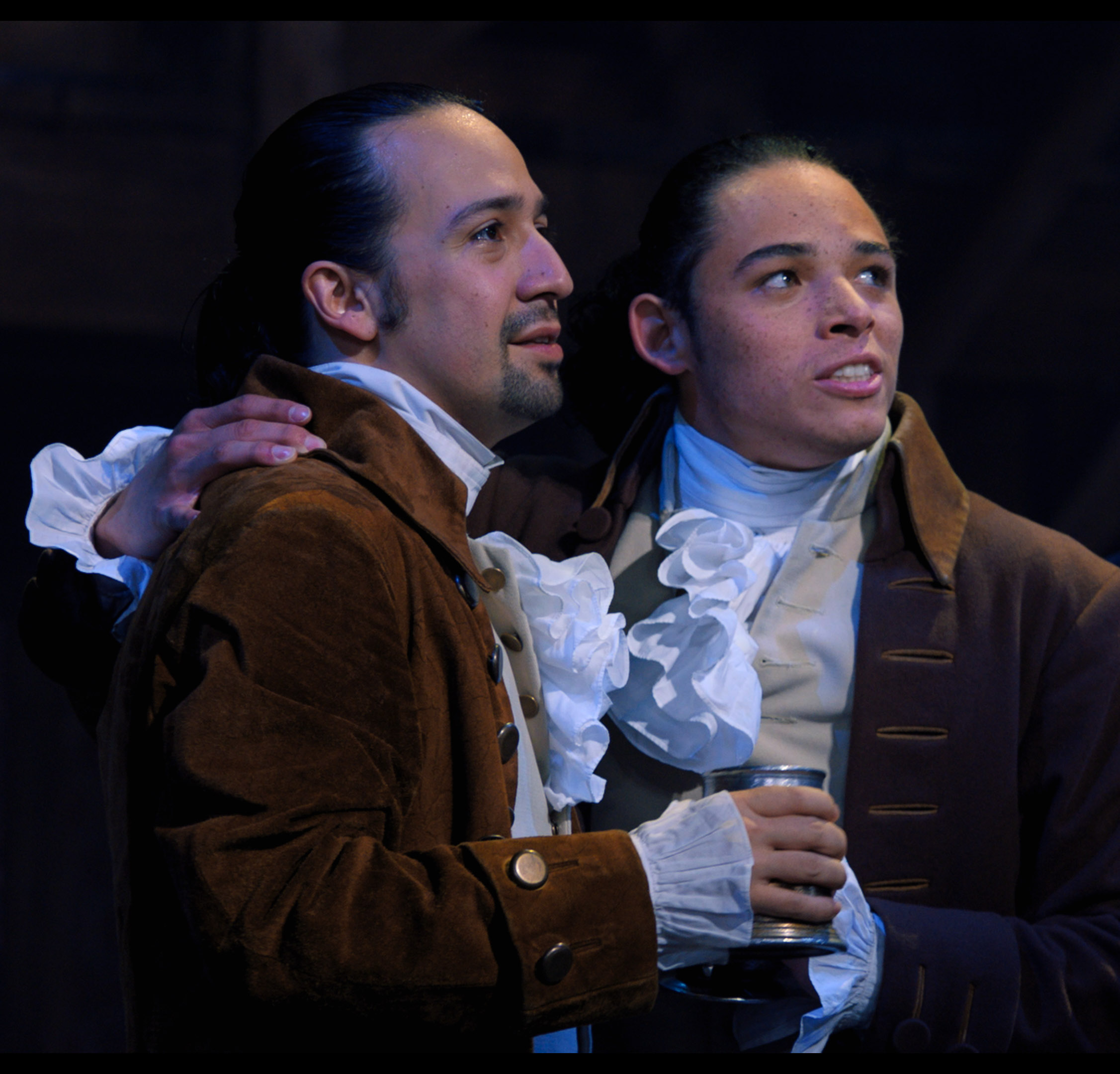

The final step was — once we had gone through the first set of approvals — was showing it to Lin, which is the most nerve-wracking thing possible because he’s the creator and the genius behind all of the words that you’re listening to and obsessing over and the music that you’ve fallen in love with.

But, he is probably the most generous audience member I’ve ever encountered – that’s not to say he doesn’t have notes because he does. He knows this play. He wrote this play. This is his mind, so his insights were incredible and invaluable, but he’s just a gentle person and a lover and he shouts out when he’s excited. So his notes are mostly just right there while you’re watching. You can tell that he likes this part, because he’s hooting, or maybe he’s shifting a little in his chair during a moment – we’ll have to look at that. You can just read the room with Lin.

HULLFISH: How long had you been working before he saw it?

MORAN: I think he saw it in early January, so three months.

HULLFISH: That’s a lot of work to go through and then here comes the proof of the pudding.

MORAN: Tommy and Lin do share a brain a little bit. I had confidence that if Tommy is happy, I think Lin’s gonna be happy. He’ll have his specifics, but if I’m making Tommy happy, I’m on the right path.

And Alex and Andy, they’ve been course-correcting us. Once it was through all of those amazing hands, I had a pretty good sense that it would go well with Lin, but you never know and it’s scary to sit in a room and show somebody their thing. What if it’s not how they envisioned it? It was very much a relief to get through that with him being happy.

HULLFISH: Any specific advice you could give or tips on cutting this kind of a show or something with choreography? What are the things that go through your mind when you start into a dance number?

MORAN: The first thing I would say is just let the thing be what it is. You have to trust the material. Try and stay out of the way of it as much as possible.

It’s a cinematic form, so you want to be expressive and make it emotional, but I think there’s a tendency to over-cut and over-manipulate material. You have to sort of believe in the art and what it’s doing and let that be on display because that’s the reason it exists, the reason why it’s important enough to document in this way. That would be my advice.

Then, know when you want to step in and put a little bit of perspective on it. I still have a little bit of consternation about the “Satisfied” “Rewind” section. I love it and it’s visual and I feel it’s expressive of that moment, but I also think, “Maybe we should just watch the stagecraft there” But that’s not the medium we’re in and the medium we’re in is a visual storytelling medium and that’s when I feel like you want to use the tools available to you as a cinematic storyteller.

That moment is an exciting moment, and so how do you express exciting moments? What’s the most engaging way to express this moment?

HULLFISH: I don’t mean this in any kind of a negative way but that’s one of those places where I felt the editing.

MORAN: Yeah.

HULLFISH: This is a place where it’s supposed to be confusing and it’s the big Rewind right? This is the place to do those cuts.

MORAN: The language that they’re working with on the stage is that they’ve broken the thing in a way. The play is going backward right now. Something just changed and it’s confusing and it takes you a second to kind of realize what it is.

And this came from my first viewing of the show. When you’re in the theater and that’s happening you’re thinking, “Wait! What? What is happening right now?” And honestly, until you’re dumped into the dialogue moments I was thought, “I think it just went into reverse! I think we’re in a previous scene right now! Wait! That’s definitely from a previous scene! I’ve heard that before! Oh my God!”

I wanted people to have that, where they’re wondering what’s happening. It’s kind of exciting and “Whoah! The lights! It’s crazy!” So I was just trying to express through editing there what I was feeling.

HULLFISH: I think you did a great job of that. That was definitely the feeling I got from that scene.

You cut narrative stuff. Do you feel like when you were cutting this project are you working different muscles? Or is it the same muscles? Is it just editing?

MORAN: It’s still editing.

When I work on documentaries, I want it to be dramatic. I want it to be emotionally engaging. That’s not to say I want to manipulate truth, but my primary interest in working as an editor, is in expressing things through the cinematic language and that’s an emotional language to me. And it’s an intuitive kind of abstract language but it’s an emotional language and so you’re kind of always trying to find what the character of a scene is what the character of a moment is and how to prop that up and enhance that.

With this, it is a bit like exercising six muscles at once. Like tapping your head and rubbing your belly. Because you’re not just telling a dramatic story, you’re trying to figure out if you can tell that dramatic story and also see Sasha in the background doing that motion that’s going to carry you into the next thing and show what is happening on the stage.

That’s true of narrative stuff as well. You’re always looking for ways to link your shots and tie things together and making a fluid experience for the viewer. It was sort of like an extra thing of: can I continue this dance move from that wide into this close up and then I know I need to get back out because we have to see that whole stage picture.

That wouldn’t be as tough if I were in a more traditional narrative space. To your question about compressing time: in a narrative space you can generally find an opportunity to extend a moment a little bit, so if you need to resolve something in one shot you can hang there and then cut to a wide or a medium where the scene continues and you can find a way to sort of fudge and extend a moment where the continuity works and at the moment is as big and as long as you need it to be to resolve whatever’s happening in your primary shot.

I was definitely more bound in by the rules and the timing of what was happening on stage. The rule was: “it’s live.” This is the stage play and that is what we’re showing.

We’re telling a story of Alexander Hamilton and this whole incredible period in American history, but we’re also telling the story of what happened on that stage. That was definitely an edict that guided our choices.

HULLFISH: In a narrative, you might say, “Oh here’s this big moment where his wife finds out he’s cheating on her” and we want to give some space for the audience to take that in, but in the workshopping of the play and in doing this night after night, they’ve already built in that time because they know the theater audience needs that time too.

MORAN: Absolutely. When you have these contemplative moments with Burr standing center stage just thinking, reflecting on what Hamilton’s life has meant to him, feeling the impact of those things, the show has those moments built into it. It’s just highlighting them and isolating them has real power. That’s actually the power of what this presentation is. When you’re in the theater you can watch anything.

HULLFISH: Meaning you can look at a background actor or you can look at the person speaking?

MORAN: Yeah, absolutely. We’re giving weight to specific things and we’re focusing on what Burr’s reaction to Hamilton endorsing Thomas Jefferson is. And that’s a significant moment for Burr and that’s something you would do with a cutaway in normal storytelling and that’s why you have to be so careful with your close-ups because they have to mean something.

When you cut to Burr for that moment, it’s because that’s fracturing his soul. That’s a moment that breaks him and turns him into a person that’s willing to have a duel and kill this man, ultimately. And so using the close-up and the language of cinema there is helpful. It guides the storytelling and that’s something that’s there on the stage, of course, because those guys all want you to notice that, but you might not.

We have the power and luxury to guide that and make it expressive in that way but that all comes out of what they’ve built and how they built those moments into this entire tapestry which is just incredible.

HULLFISH: I get teared up when the Hamiltons’ son dies and Eliza screams that anguished scream. What happens there in the edit? Do you remember building that, or thinking I’m just going to stay with them? What was the editing process for that moment?

MORAN: It was that. That’s a moment that what’s happening between the three of them — Hamilton, Eliza, and Phillip — that’s a moment you just want to stay out of the way of as much as possible. More than anything I just wanted to be in the right position to see the work that they were doing. You want to see what Anthony is doing as Phillip on the table there, see his face and the sweetness and sadness of that as it twists and fades from life. And Hamilton knowing he’s responsible for sending him out there with his guns and Eliza kind of knowing that too and watching her son dying and trying to hold onto him. It’s heartbreaking.

The work that all three of them did and the staging of that on that table at the front of the stage and the lighting. Everything was perfect, so you just want to stay out of the way and let that work be absorbed.

HULLFISH: That moment is played pretty much on that one 3-shot, right? A front-facing fairly close 3-shot but not close-ups. It’s not: “go into the mom’s anguished face” kind of thing. We need to see all three actors and their interplay.

MORAN: We experimented with going closer. We definitely experimented with all those things, but you don’t want to break the spell.

If you cut too much it feels like maybe you’re faking something. There’s a real tear that streaks down Pippa’s face there. It’s just amazing. It’s just a beautiful thing to watch and I don’t want to cut away.

As an editor, I’ll often try and break a thing. I’ll push it to where it’s broken and then you kind of pull back again. I did that a lot throughout the process. Tommy’s a great guide for that because I would push things and show it to him and if he liked it, it would be great. Occasionally he’d warn me that I’d gone a little too far and just pull me back.

HULLFISH: Is the end of that scene the stagecraft of the lights going down? Did you fade? I can’t remember how that ends after she screams.

MORAN: The light does shift but the turntable rotates them off to stage right and Angelica comes in and sort of begins the “Quiet Uptown” song about loss.

HULLFISH: Did you — during the course of this — look at any other filmed theatre productions like operas or something?

MORAN: Not specifically honestly because I didn’t want to get too dragged into other people’s language and what that had been.

There’s a live-filmed version of “Rent” that’s probably my favorite. Coincidentally, Rene played Mimi in that, It was the first time I remember ever seeing Rene and she is spectacular, so you should check it out for that if nothing else. Renée Elise Goldsberry plays Angelica Skyler of course in Hamilton.

In the “Rent” filmed version, they really brought in the language of cinema and introduced it to the language of theater and it’s a vivid exciting telling of “Rent” using perspective, and the things that we use in cinema is to tell that story and to highlight things.

“Rent” is another show that had just so much going on. And when you’re cutting two characters saying lyrics, suddenly you can see, “That’s who’s talking! That’s what’s happening!” It focuses you in a way that’s powerful. That’s probably my favorite example of something like this.

It’s a very different approach because rent is a very different play. There’s a lot of hand-held stuff. It matches “Rent’s” gritty storytelling.

HULLFISH: Thank you so much for talking to me about this project. It’s really interesting to hear the ins and outs of it and your decision-making.

One of my favorite quotes was: “Just don’t break the spell.”.

MORAN: Yeah definitely. Never break the spell. It applies to every form of storytelling – cinematic and otherwise.

HULLFISH: Thank you so much for being with me today.

MORAN: Thank you. Thank you so much for doing this and thank you for taking the interest.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed, and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now