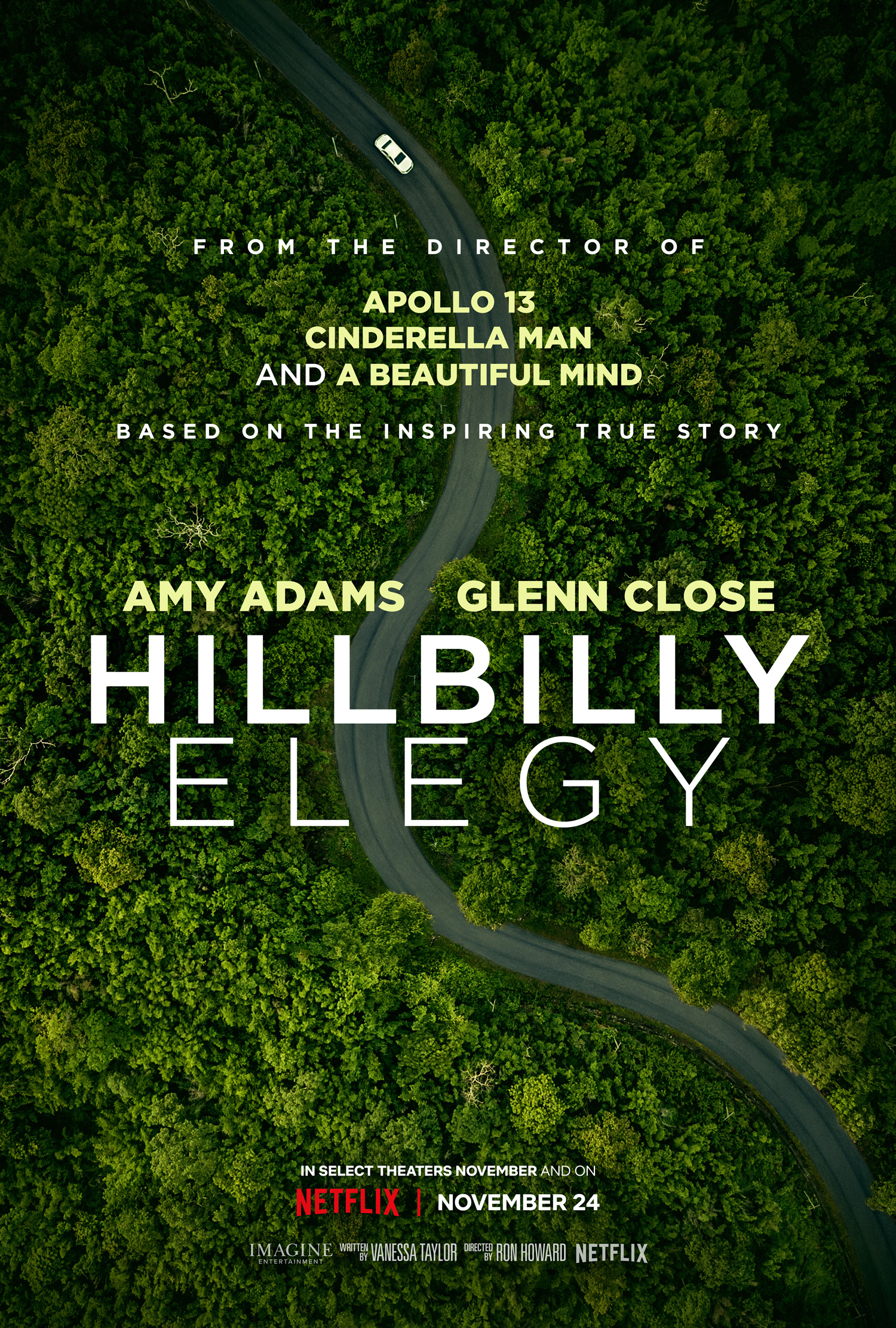

In this interview, James D. Wilcox, ACE discusses editing Ron Howard’s new film Hillbilly Elegy, which is available now in select theaters and on Netflix.

Ron Howard has edited nearly all of his films with a pair of veteran, Oscar-winning editors – Mike Hill, ACE, and Dan Hanley, ACE. I’ve interviewed Mike and Dan before on Art of the Cut for In the Heart of the Sea. Attempting to fill their shoes is a daunting task, and one James is clearly up for.

He won multiple Emmys from his news editing days and an ACE Eddie for his editing of the original Genius series pilot, Einstein: Chapter One. His other work includes TV series, Everybody Hates Chris, Roots, Hawaii Five-Oh, CSI: Miami, Dark Angel, Hand of God, and Reno 9-1-1. James is also a director and was nominated for a BET Comedy Award and an NAACP Image Award for directing My Wife and Kids.

This interview is available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: James, It is so good to talk to you again. You had some enormous shoes to fill. You had two guys that had been cutting for Ron for years — and not only just one but two. And now you’re taking place of both of them. Tell me a little bit about the apprehension or the challenge of doing that.

WILCOX: I’ve never contrasted myself against Dan Hanley and Mike Hill, and Mike I never met. Dan, I met on Genius and we really formed a friendship after that because that’s how I came to know Ron as well.

The challenge of filling in for two Oscar-winning editors and working at that pace — because Ron was used to that triangle of editors that he was working in and he could bounce from one room to the next and give notes and come back and then see how the notes were advancing and they just had a well-oiled machine down.

Then Mike retired after In the Heart of the Sea, and Dan after Inferno — that was his last feature, and then Dan went over to do Genius and that’s where I met him. Then he retired shortly after that, so that left an opening and then Ron had gone off and done Solo. Pietro Scalia had cut that with him and then Hillbilly Elegy came up and I was in Ron’s sphere from Genius. Through a series of convergent events, we ended up hooking back up.

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about what happened on Genius that kind of got you into the driver’s seat on this one.

WILCOX: I give a lot of credit to Dan about that because on Genius I interviewed with Dan and another Imagine executive and the showrunner of Genius — the first season — that I had known from previously working on James Cameron’s Dark Angel series, so when I went in there was a little bit of familiarity but I didn’t know Dan and I didn’t know the Imagine exec.

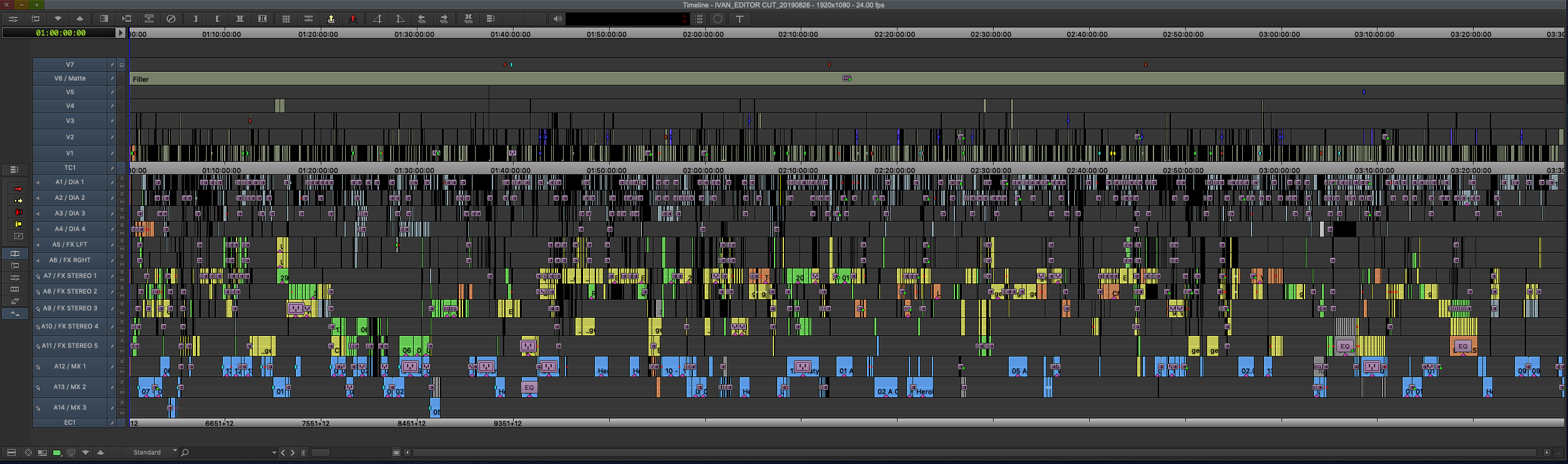

We did the meeting and the whole idea was that Dan was going to work with Ron to form the look of the first season of Genius — to get the pilot off the ground. Again, Ron was used to two editors, so he brought me in because there is a distinct advantage to having two editors. You can work, theoretically, twice as fast and you can get two different opinions that collaborate independently from the director as well as with the director. So there’s a lot of pluses to it.

We did the meeting and the whole idea was that Dan was going to work with Ron to form the look of the first season of Genius — to get the pilot off the ground. Again, Ron was used to two editors, so he brought me in because there is a distinct advantage to having two editors. You can work, theoretically, twice as fast and you can get two different opinions that collaborate independently from the director as well as with the director. So there’s a lot of pluses to it.

So they hired me to come in and assist Dan in forming the look of a Genius but coming off of Inferno and the long run of illustrious films that Dan had done with Ron, it was one of those things where he called me and he said, “James, I think it might be time for me to retire,” because these films take you on the road they take you away from your family a lot. There’s a lot that goes into it that’s not so glamorous. There are real sacrifices. And I think that Dan was just ready to kind of settle in and reconnect with this family and his life.

So he felt good enough to have Genius in my hands that he could comfortably retire and then I inherited Genius by myself. Then Ron and I started working together. He was shooting in Prague and we never really actually met until shooting wrapped and he came back, and that’s how it all kind of began.

In the process, I was sending him cuts of various scenes — this was part of the workflow that Dan and Mike had created — and you get some feedback early on. So everything’s not piled in the corner until you wrap shooting and then you’re getting all the notes at once. So there were things that I could get an early jump on and it helped me connect with Ron so I could understand his sensibilities and he could see how I saw the material.

We meshed really, really well. In fact, the performances were the things that he articulated the most that he liked about my work. From that point on, we came in, worked together in person, shoulder-to-shoulder. It was great. We had a wonderful time, albeit brief, and that was the beginning of our working relationship.

HULLFISH: You said, he liked “the performances.” What you mean, I’m assuming, is that your. Take and his take on the actors’ performances is a really important thing to mesh on.

WILCOX: Yeah. For me, Steve, it’s probably the most important aspect of filmmaking for me as an editor is performance choices — laying out characters and looking for moments that aren’t scripted, looking for real moments of human behavior and the dynamics between people.

I think once an editor is able to decipher what they’re looking at and they can go beyond the script, that, I think, is what makes a film special and what separates editors.

For me, I got a firsthand dose of acting experience because I was in Beverly Hills Playhouse for three years and I’ve done some directing so I can approach my editing from what the director sees and how I interpret what the director is giving me to work with, but also those actors’ intentions and choices on how they’re arcing their character, and what I need to do to influence that work overall and to understand what those choices are.

To correct myself, what I meant was, Ron really liked my performance choices as it related to the actors’ choices and how he saw the scenes unfolding on set — sometimes accompanied by notes and other times what we tinkered with and came up with in the edit.

HULLFISH: There’s a scene in Hillbilly Elegy in a car, right after JD has bought a calculator and I was curious what kind of colors or tones or temperatures of performance you were getting.

Talk to me about constructing a scene like that where you might have different colors of performance.

WILCOX: That scene is really interesting. You’re talking about the scene where JD has stolen a calculator, there’s been a lot of pressure on him. He’s at one of the most troubled points in his life. He’s 13 years old and he hasn’t been doing his homework. He’s a very bright kid, but he’s just slipping down a dark path and his grandmother recognizes that.

He’s gone into Radio Shack he’s stolen the calculator. She’s found out about it. She’s come to get him and she’s going to have this come-to-Jesus talk with him. So they’re riding in the car and he’s frustrated because she doesn’t like the people he’s hanging around with. She sees that his life is going off the rails. It reminds her of how her daughter’s life went off the rails. How the environment and hanging around with the wrong people can just eat you up.

So she comes to pick him up after he’s been busted for stealing the calculator and she starts laying into him and tells him, “You gotta get new friends. You gotta get it together. You’re 13. I’m not gonna be around forever.” And he’s frustrated with her. He wasn’t supposed to be living with her. He’s supposed to be living with his mom. So they pull the car over and she starts talking to him.

Now, we’re shooting this scene in Georgia. It was a very humid, hot day and everybody was worked up. You could see that the heat was affecting performances.

Glenn Close, who plays the grandmother — she’s kind of red. She’s kind of sweaty. This was a very hard day for everybody because they’re sitting in the car. The windows are open. Then you have all these variances of performances.

She starts by giving him a very civil talk about how he’s got to pull his act together. How people like them don’t really get a lot of chances — and by that she means they’re poor, underclass people who don’t have privilege. They don’t have legacy in their family. They don’t have a lot of opportunity and they’ve got to make the most out of it, and that’s just to have a chance to succeed. So that’s the gist of her argument, which is actually a very universal speech that a lot of mothers — grandmothers, a lot of strong women — have told their children, their sons, their daughters as they see them going off the rails.

So in that scene, you have variances. Glenn Close starts with talking to the young boy, JD, very civilly and that tends to elicit a reaction from him that is about the same. Then Ron went in and adjusted some performances — suggested to Glenn, “Maybe you can try this a little angrier at him.” And it worked a little better. Then we kept going until we finally got to that one take where she was just on fire. It brought a frustration out of him that was just completely unscripted at times.

At one point he blurts out, “I hate you! Why did you even want me?” And she tells him, “I don’t want you. This is just the way it is.” So, it’s a real growing-up, coming-of-age moment, but it was very difficult because as I was putting my cut together, that was one of the last scenes that I cut.

I knew that I wasn’t fully satisfied with that scene and I knew that that scene was gonna take more time to get to my satisfaction and ultimately for Ron’s approval and his satisfaction, so I cut it — and it was great, the first pass of it — it was good enough.

But then we dug into dailies — and this is where a second editor would have helped, but instead, I sent Ron down the hall with one of my assistants and they just looked at takes and then they pulled some selects aside and they gave it back to me. He said, “James take a pass at some of these takes. On given lines try this one. Try that one.”

Now the trick becomes, Steve, as you know, moderating those performances – because Glenn’s sweating in some of them. Some of them she’s just in a different emotional state. So we found a sweet take, and then along with the other pieces, we were able to get a performance that hopefully feels seamless as she gives this kid the talking-to of his life.

HULLFISH: That was one of the reasons why I wanted to talk to you about it. Because I know the variation that you probably were dealing with, and to make it feel like it was one take is awesome.

WILCOX: I can’t take full credit for that — even though a big part of it is me to be the architect of that scene — but you have to give a lot of credit to the brilliance of Glenn Close, who, once she finds what that note is — what that temperature is — that feels right for the scene and right for the moment, along with Ron’s direction that she then hovers in that acting space — in that choice space — and says, OK. I can go more if I want, but not less because this is where the scene is residing now. So they truly have found the scene. And then she works even better with her choices from that place going forward.

HULLFISH: Absolutely. Did you read the book before you interviewed or before you edited?

WILCOX: I did. When we were having early conversations about me being in the running to cut the film I immediately went out and bought it because I really wanted to know who this guy — J.D. Vance was. I had seen him on MSNBC a couple of times and listened to some sound bites here and there, but I had no idea of his background, his values, what made the guy tick.

And so I went out and read the book to see who these people were that were around him — who the key figures were in his life so that when Ron and I had a conversation about it, knowing that it was a memoir and he was going to hone in on specific moments in his life, I’d be well versed in that.

And then there’s also this. It’s a biopic, so you want to be honest and authentic to what the story is. Oftentimes, I referred back to the book in moments of indecision as I was cutting. “What did he say here? What did he do here?” It was like my compass. It oftentimes informed me of my choices.

HULLFISH: Is there a danger that you know the story better than the audience might?

WILCOX: There’s always that danger. I give the audience a lot of credit. I’m not one of these editors who feels like the audience doesn’t know anything, because I think people are very sharp and very smart and they catch on quickly. They understand what’s going on.

And that was the beauty of having a lot of screenings where we could modulate what is happening with what we know about JD versus the audience.

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about intercutting. The first time that I noticed it was intercutting between two simultaneous events — the swimming hole and the mom wanting to pack up and leave and JD. is not there because he’s at the swimming hole.

When you’re intercutting scenes, what is something that helps you know that moment that propels you into the next scene, or is it just time to go to the next scene?

WILCOX: It’s a little bit of both. That moment where you decide to depart depends on what you’ve left the audience with. Do they know enough to not carry through the rest of the scene? It’s a “high point” thing. You want to get in at the peak and you want to get out at the peak.

You hear editors talk about that and that’s true and that’s how we work. But I also want to make sure that the audience is really clear and informed when we depart and where we’re going next, that they’re not lost because cross-cutting can oftentimes do that. Time hops can oftentimes do that.

That scene — the opening of the movie — really was rejiggered because it really started with his grandfather on the porch sitting with his uncles as JD’s mom comes out and she wants to know where JD is. JD is biking down this country road and he finds a turtle and he tries to return the turtle back to where it can heal.

Then she came out a second time and she says, “Why isn’t everybody packed? I’m ready to go back to Ohio and leave Kentucky.” I thought — after a couple of screenings — because Glenn Close and Amy Adams are such titans on-screen — it became a little confusing to the audience as to whose movie this was. Whose eyes are we entering this movie through?

So I decided to drop a few scenes. Starting at the swim-hole put the audience ahead of JD’s mom, and I didn’t like that. I thought that we should come right out — show JD, establish him, this is the guy, this is the boy whose story this is all about — and then have Bev (Amy Adam’s character, JD’s mom) come out and ask, “Why isn’t anybody packed?”

Then we find that he’s gone swimming. He’s trying to get one of his last swims in before it’s time to pack up and go back to Ohio. I just don’t like when the audience is ahead of some of our characters because we’re playing catch-up and I think it bores an audience unless that information is left there to maybe misdirect the audience.

We just needed clarity.

HULLFISH: It sounds like it also helped center the audience on the right character. Right from the very beginning, you know who you’re following.

WILCOX: It allowed us to be a little more traditional that way and understand clearly that this is who we need to pay attention to and everyone else is in his universe. They’re surrounding him but he is the focal point of the story.

HULLFISH: Was that family photo montage at the beginning scripted?

WILCOX: No!

HULLFISH: Oh tell me about that! I loved that family photo montage.

WILCOX: Ron Howard will be very happy to hear that you loved that. It started with the one photo where the grandmother says, OK everybody. “Let’s gather around and get the family picture before we go.” It was a tradition.

Ron saw that and I could tell something was brewing about that. It just felt a little unsatisfying to him. He came in one day and he said, “James, What if we built that out?”

I just got some pictures off the internet that looked like they could be the Vance family throughout the years. And then we started playing with the length and how many pictures we would have and we knew that part of JD Vance’s legacy and part of his family history is that he has a connection to the Hatfield McCoy feud.

I knew that if we could find one of those historic photos — to end on it — that would be good because that comes up later in the movie. I can’t take full credit for that. It was Ron’s idea to embellish it and beef it up. It’s like a history-in-brief of the people in the region, of his family, and the tradition. And it’s a great 10-12 second way of giving the audience a lot without dialogue.

All those photo selections were pretty much mine — approved by Ron.

HULLFISH: Did you have to photoshop them? I thought a couple of them looked like they were still the same family members.

WILCOX: We tried to anchor those pictures to the place itself. So if you look at the place — the house that they’re standing in front, of that porch — we had to do a little VFX work to characterize that house throughout the years.

You could see that work had been done on the house as it became older and older, but essentially the first three or four pictures are the same house. The roof has been tweaked a little bit but we went in and made sure the beams were painted the same color, so there was some continuity anchoring it to the actual house down in the holler.

HULLFISH: I thought it was interesting when you went to Middletown for the first time there is like a flashback and you don’t just go back and kind of stay back. It goes from present-day to past to present as they return back to his hometown essentially.

And it’s also the beginning of establishing going through that tunnel as a motif that you see throughout the film.

WILCOX: That’s a great question because what we were doing was a lot of non-linear storytelling just with imagery. When the family leaves the holler in Kentucky for Middletown, we start telling the story of how Jim and Bonnie took off (JD’s grandparents) at an early age to go up to Ohio for a better life.

It’s supposed to be juxtaposed and contrasted with where the family is now and you see that as they enter the town this big factory that is going to be the jewel of employment for Middletown, Ohio. And then you see as they get older and they’re returning back from Kentucky you see how the factory is closed down now and how the town has fallen.

ÒAÓ camera/steadicam operator Christopher TJ McGuire and Director of Photography Maryse Alberti on the set of Hillbilly Elegy.

Cr. Lacey Terrell/NETFLIX

Going through the tunnel signifies so much. In some ways, it’s like a birth canal. It is met with hope and it is met with trepidation and it is met with — ultimately in some ways — a relief. It comes full circle. I don’t want to give the end of the movie away, but that tunnel took on a lot of significance throughout the movie because a lot of people — when they go back home — they have feelings of anxiety. Can you return home? What will home be like? It’s illustrated through that tunnel.

I come from Pittsburgh and I have a lot of regional understanding of what happened in the movie. At one point — at soon as I graduated high school — I worked in a steel factory because that was still the number one driving source of employment in Pittsburgh — and in the region — between Ohio, West Virginia, Kentucky, Pennsylvania.

As a result of that, I had a lot of connection to what JD Vance, and the Vance family, and that culture, was going through — albeit our dynamics were different but I understood that. So I understood a lot of what it meant when he went through the tunnel — when people would go through the tunnel — because Pittsburgh is a city that has a lot of bridges and tunnels and mountains and so when you enter Pittsburgh you have that same feeling of “what is this going to be like?”

HULLFISH: I love your emotional understanding of the characters and of the film itself. I really think empathy is so important in an editor. Can you just talk about empathy for a while and how that shapes what you do?

Director Ron Howard and Producer Brian Grazer on the set of Hillbilly Elegy.

Cr. Lacey Terrell/NETFLIX

WILCOX: Steve, I think empathy is probably our single biggest relied upon trait as an editor — as a storyteller. In general, I think writers, directors, editors, production designers, anyone that has a significant influence on a film needs to have a lot of empathy.

I’m going for authenticity and legitimacy in my storytelling. That doesn’t mean that when I cut a movie or a show or a TV show, you have to LIKE the characters. My job is to help you UNDERSTAND the characters — and then if you’d like them that’s even better. If you don’t like them at least you understand — through empathy — why you’re feeling the way that you are.

In Hillbilly Elegy, it’s a real challenge to establish JD’s mom — who struggles with addiction and who struggles with a lot of personal issues — to get the audience to understand what it is about her and why she’s in the state that she’s in. That, for me, requires no judgment. What happened in real life? How do I characterize this on-screen with the choices that I’m given to work with?

I approach everything — every character — from an empathetic point of view because that’s what connects us all. That’s my firm belief.

HULLFISH: There’s an early law dinner table conversation. JD’s trying to get a job with this law firm. He goes to this dinner trying to impress some people and it’s about eight people around a table.

Those scenes are really difficult to cut because of eyelines and stuff. Could you talk about the technical aspect of trying to even organize the material so that you can properly execute that scene?

WILCOX: Those dinner table scenes — sometimes courtroom scenes — challenge an editor and they challenge a director. Even before you get the material, the director is challenged. You have to spend the proper amount of time to pick up all those eye lines or you’ll be on the wrong camera at the wrong time when that actor — and their scene partners — aren’t interacting.

When you have a main character like JD at a dinner table where he is talking to seven other people, you have to have all those eye lines to draw those personal connections between those characters, or else something feels off. You have to do it over and over and over again when you’re shooting it.

You really need very disciplined actors who understand that if they took a drink of water after a certain line that every time they need to drink that water after that line, or now you’re into this territory as an editor — I call it defensive editing. You’re not really being able to do what you want with the material, but the material kind of is having its way. So you’ve got to cut away to something else to come back and then get back in your pattern.

Sometimes it’s not a big thing because I’m trying to cut the scene on multiple levels. There’s “actually what’s happening” and then there’s “apparently what’s happening.” And so the actual happening at the dinner table sometimes may be more interesting by-play between two other characters as relating to the main character.

So you have all those choices but they really do challenge the editor and the director on how they’re shot. And when they’re not shot properly or cut properly boy, they stick out. And it’s funny too because those scenes oftentimes have the irony of being really long scenes.

In addition to the challenge of all the eye lines and making the conversation work and being at the right place at the right time in the right size and in the right performance, those scenes oftentimes have that duality of being really long.

HULLFISH: You’re trying to keep them interesting.

WILCOX: Yeah, because that scene you’re talking about is approximately a four-minute scene!

HULLFISH: Normally an editor would have his assistant organize his bins so that it’s wide shots, then two shots, then close-ups of one person, and close-ups of another person. Do you then organize in the bin by eye line to specific characters?

WILCOX: I have my assistant organize everything in groups. The frame representative of each camera tells me and informs me of what I’m looking at — the size that I’m looking at. I don’t really get too technically into the eye lines until I’ve mastered the performance first. So I go in and I look at building up all of the performances. What are the best takes? What are the best performances to use?

And then Ron, when he’s directing, he shoots with a lot of detail, so you may have food on the plate, there’s bread that’s being put down, the waiter is coming by and he’s pouring wine and so you have a lot of business that’s happening at the same time.

So I tend to not really get too hung up on the eye lines but I deal with the performance and the takes and the delivery, and if that’s satisfying to me, then I go in and say, “This point is where we need to be in close.” So I’ll start looking for that structure of eyeline secondarily after I’ve already cut the scene.

Those scenes that are four minutes? I just chip away at. I’ll take a minute or a minute and a half — that’s a sizable part of my day — I’m happy with it. I’ll leave it alone. I’ll go away from it — cut something shorter. Leave it alone until the next morning. Come back the next morning, review it and see, “Whoops. I actually missed a beat here. There’s something I need to include. I need to be on the other shoulder of this character rather than the one that I currently cut.

It can get a little overwhelming with the amount of footage. You’re just trying to get through it and digest it and then I’ll come back in the next morning and it’s amazing what being away from it for 8 — 10 hours will give you — the clarity that it allows you to have, so that’s what I tend to do.

Then there’s also the overlapping dialogue at times, too.

HULLFISH: Talk to me a little bit about patience and how — as a more experienced editor — that’s something that you’re coming to embrace.

WILCOX: I spend tons and tons of time with every single scene — sometimes to the point where I back myself into a corner, and the schedule kind of doesn’t work in my favor anymore.

At the end of the day, people don’t go to the theater to see my schedule. They go to the theater to see the performances. So any amount of time that I have to invest in it — and I had two Oscar-nominated actors and an Oscar-winning director — I know the choices are there and I want to put the time in to make sure that I’m making them happy and servicing the story. It sometimes absorbs way more times than I think it could for other editors. But I just don’t give up on scenes and I know how I need these micro beats to land in these big moments.

Once I get it to a point where I’m generally happy with it, I will leave it alone — sometimes for two days. One of the luxuries of me working in features — as opposed to television, where you don’t always get that second look back at things or the third look back at things as the schedule rolls forward — but on this feature, I was able to leave things on the shelf for a couple of days, come back, look at it, bring my assistants in and get a second opinion, maybe change takes, and as the movie evolves it’s informing me of what I need to be doing at that moment.

For instance, here’s an example: with Amy Adams’ character, Bev, when we first meet her, she’s in a big hurry to get back to Ohio because she considers Kentucky to just be way too slow and country and just not interesting for her at all. She’s just more at home in Ohio so she wants to get out.

In my first pass, she came out and she was really sort of aggressive about how she was telling her mother — Glenn Close — “We got to get out of here. I want to get back to Ohio.” But as the movie evolved and I got down the road with her with various scenes, I realized that I needed to tamp her down in the beginning because she has some big moments — big emotional explosions and implosions downstream — that I needed the audience to be on board and just like her, understand her, use takes where she’s smiling.

When JD gets back home in the truck with his uncles and she asks, “What happened to you?” He tells her he got in a fight. Well, she’s kind of smiling through it, but she also wants to know: “Did you stick up for yourself? Did you do the right thing? You didn’t let anybody pick on you right?”

It’s more of a momma-bear moment than her being unstable. She says, “I’ll kill him” but she’s just sticking up for her son as any mother would do when they see their child’s been threatened or injured. So those kinds of things inform me as I build out the show — what I need to do with performances. That’s why I end up spending a lot of time on performances all across the board.

And in that scene, you’re talking about, with her driving in the car just after they’ve come from the card shop. That scene — there were so many different choices — but I needed to see vulnerability from her. I needed to see how, in the beginning of that scene, as they’re driving along and settling in that she’s really trying to build up her nerve to suggest to JD that they move in with this new boyfriend of hers.

She knows that JD is not going to be on board with that because he’s already experienced the outcome of her living with multiple partners in different places. But as the conversation continues he understands that this is a bad idea, and then he makes the bad mistake of saying that one of his friends calls her, “flavor of the month” and that sends her off into a deep regression of anger and anxiety and lack of appreciation.

So I had to go back in there and really look at her performances — take after take — especially to see when he says “flavor of the month” —. how is she wounded? I want her to be upset about it and react to it, but I want her to see that she’s really genuinely hurt. She has feelings too. Despite what you see about her, and how she can go off the rails at times, she’s a person that has a big heart as well, and that she’s wounded by that.

That is a lot of careful crafting for that scene and a lot of Amy’s performances as well as Glenn’s.

HULLFISH: And a lot of it has to do with context right. As you said, you got these temperatures of performance throughout and when you’re cutting the scene the first time, I’m sure there’s that thought of I’m going to go for the most dramatic performance I can. And then you realize the whole movie cannot be the most dramatic performance, right? It’s like a dynamic in music… it needs peaks and valleys.

WILCOX: That’s exactly right. That’s a great thought. Because you do have to earn the place where you’re at in the movie and you need to build to it. With a character like Beverly Vance who was so unpredictable and spirals out of control so often, you have to really have people not really like her and understand her in the beginning, so that you have somewhere to take the character so that people can understand: this is why she’s the way that she is.

HULLFISH: These performances! I told somebody since I’ve watched it, I’m putting my money on Oscars for both of them.

WILCOX: That would be lovely honestly.

HULLFISH: And I’ll put you up for one, too!

WILCOX: I’m happy to just be on board and play my part, but I have to tell you — for those two women, I don’t know how they both aren’t multiple Oscar winners by this point in their careers.

To see their work ethic. To see them sacrifice so much under the conditions that they were working in — not bad conditions, but I’m talking about the weather. Shooting in south Georgia at times where it’s 100 degrees and it felt like 100 percent humidity and they’re out on these open roads with the sun beaming down on them. And there are prosthetics involved and clothing that’s not necessarily favorable to the weather and just the loss of vanity.

The physical characterizations from the real characters that they embodied. They really sacrificed a lot. This was a truly tough, tough gig for both of them, and I just stand in awe and appreciation for them, and I do hope that it results in Oscar wins for both of them.

HULLFISH: Amen. Is there a trick to dealing with hand-held footage? I didn’t recognize how much there was, but there was some handheld footage. Is there a key to cutting that?

WILCOX: There’s quite a bit. I’m a big “rhythm guy.” There are a couple of things with handheld that I love. The imperfections of the frame. The suddenness of it. The operators understand the scenes and the moments, but you’re really giving them a lot of credit to tell the story in a handheld way you get more improvisation that way. It’s almost like a jazz player where they’re listening and they’re paying attention and they’re deciding, “Something happened just to the left over here. Whip over. Get that.”

It depends on the type of scene. I love handheld for so many reasons. It gives you an unstable energy at times. It gives you a suddenness. It gives you that human element where it’s more experiential and less observational. So I really, really dig handheld a whole lot.

Now what handheld can oftentimes do is — if I’m cutting between handheld and sort of “studio mode” then I might have to put a little movement on it myself to create a rhythm so that it doesn’t feel staccato so that you’re in it and you don’t really feel that there’s been motion and movement to a sudden stop and then you may go back to motion and movement again. So I’ll just put little creeps on things just so that there’s some fluidity between cuts if I have to do that.

HULLFISH: That’s a great tip.

ÒBÓ Camera Operator Tom Lappin, Director Ron Howard and Amy Adams on the set of Hillbilly Elegy.

Cr. Lacey Terrell/NETFLIX

There’s a montage where Amy Adams’s character is roller skating and there’s some crazy sound design in there. Can you talk to me about sound design throughout the movie and how important it is?

WILCOX: I wanted to sound design it in a way that was interesting but also documentary-like and extremely in the point-of-view of the character that we were dealing with.

So for Amy Adams, you’re talking about the scene where she goes into the break room, she’s taken some pills, so she’s feeling buzzed. She’s talking with one of her co-workers who is a skater and she asks to borrow the skates — takes over the skates — tries them on and down the hall she goes.

It’s really interesting because as she was skating it brought back a personal feeling of mine when I used to skate when I was like 15 years old. And it was like a big deal. It just took me back to a time where I didn’t have a mortgage, I didn’t have children, I wasn’t married. I felt like I related in that moment with Amy, except I wasn’t high and I would go roller skating as well. And that was just pure fun.

For a character like her who’s been through so many things — she’s lost her father, she’s had a difficult upbringing, she’s trying to raise children. It just felt like one of those moments where “This is fun Bev.” Even though it’s out of bounds It is fun Beverly Vance.

So in that there’s shifting sound design for her point-of-view. When we’re on her It’s more external and we’re experiencing and hearing oftentimes how the hospital is responding to her and the doctors and the nurses around her are thinking, “We’ve seen a lot come in here, but we’ve never seen this before.”

Hair Department Head Patti Dehaney and Glenn Close on the set of Hillbilly Elegy.

Cr. Lacey Terrell/NETFLIX

And then when we’re in her point-of-view, everything is sort of muted and warpy and a little sound designy. It happens with the music and it happens with the dialogue as doctors are yelling at her. For me, it was all about just living the experience with that character and the sound design I thought helped accentuate the fact that she was high and also it was internally how she was feeling.

HULLFISH: You’re getting to like her but you’re also realizing she should not be doing this. The audience is really kind of torn in the middle of that I thought.

Most flashbacks were done with cuts. Some of them were done with a little rack focus transition. Was there a reason for the rack focus in those places?

WILCOX: I decided that we were just going to do whatever worked. Sometimes cuts worked, one to one. I’ll give you an example of that. When JD takes off to go back to Middletown — to visit his mom in the hospital — and he’s at the gas station and his girlfriend is asking, “Where are you? You have a big interview coming up and you’re on your way back to Ohio?”

And he doesn’t tell her why. He’s a little bit ashamed to divulge that information to her for fear of losing her, and he sits in the car at the conclusion of that scene and he thinks, “What have I gotten myself into? This is heavy stuff.”

But he loves his mother and he has to go back and visit her. And then we cut to an earlier incident with his younger self sitting in the back of a police car and I thought that those kinds of 1 to 1 cuts helped you seamlessly see that from age 13 to 28 he’s been carrying a lot of burden across his life, and it continues.

Director Ron Howard and Glenn Close on the set of Hillbilly Elegy.

Cr. Lacey Terrell/NETFLIX

He’s on the cusp of a life-changing decision — a life altering opportunity — but yet this is how life is. In comes some drama. In come’s some trouble. So in that instance, the cuts work.

There were other instances where — in-camera — there was a rack focus out of the end of the shot and I didn’t want to go from a rack focus out of the end of a shot to a straight cut into the incoming shot, so we would do a little bit of simulated rack focus on the B side too.

You hit on something. Because there are so many flashbacks in the film, Steve, we were reluctant to use a consistent device that every time signals a flashback, because I thought that the audience would grow to expect them and that it might bore them. So it was kind of — in the moment, what felt best?

HULLFISH: Sure. That makes total sense. There are two scenes fairly violent scenes that are intercut — from present-day to past. Can you talk about the energy of that and how you chose the moments that they were intercut? I’m sure they weren’t exactly scripted like that.

WILCOX: No. No, not at all.

When you’re doing a biopic and you’re zeroing in on a couple of different time periods, you want to be able to unify that. JD had a lot of rage in his younger life. He didn’t have the supervision that he oftentimes wanted and he was starting to get in trouble by hanging around with the wrong crowd and he was angry. That anger still lived within him as he got older, but he just handled it differently.

Haley Bennett, Amy Adams, Director Ron Howard and Owen Asztalos on the set of Hillbilly Elegy.

Cr. Lacey Terrell/NETFLIX

So the cross-cutting of it was really: What’s the most dynamic, most energetic way to show the violence that lives in this kid? Because he’s a good kid but bad decisions can ruin us all. As they say, “There, but for the grace of God, go I.”

So this is a guy who was in trouble at two pivotal points in his life and it kind of typifies the movie in that you see the embodiment of it in one crosscut scene. And the choices made were just simply: What are the most visceral, aggressive shots that we could use to tell this story between these two time periods?

HULLFISH: I want to get back to that scene that we talked about a little bit earlier in the car with a calculator because that was a really pivotal scene.

I know that you, as a great editor, would not be trying to lead the audience with music, so I love the fact that in this very dramatic scene where you would think, “Oh, let’s put some dramatic music in there” you don’t have anything really. I think that scene plays without music except for the very end, right?

Talk to me about the choice of not placing music in a scene like that. And then, how do you determine the exact moment to spot that cue that pulls you into the next scene?

WILCOX: That’s a great question. It was a big question about when I placed it from the beginning, all the way through when we finished it with Hans Zimmer and Dave Fleming and Ron and where we thought placement was appropriate.

In that scene the rhythm of the dialogue itself is music. So you didn’t really necessarily need to push or force or sway the audience either way in that scene. I wanted it to be neutral so that there was no persuasion of the outcome of that scene. And that was my approach overall. And once I started getting dailies from Glen and Amy and I saw that they were carrying these scenes so mightily I don’t want to get in their way! They don’t need the added music to support their acting — to support what’s happening in these scenes.

Makeup Department Head Eryn Krueger Mekash, Glenn Close and Hair Department Head Patti Dehaney on the set of Hillbilly Elegy.

Cr. Lacey Terrell/NETFLIX

So placement — as well as what score we were temping with — became equally as important because I didn’t want to get in their path. I don’t particularly like that style — leading in a piece of dramatic music in the middle of a scene to underscore it, to tell the audience, “OK, we should feel this way or that way or this is how the scene is now starting to skew and sway.”

I learned a lot from that as well. I’ve been doing that before and it’s quite different than when you work in television because television is sometimes more instant and you need to massage it a little bit more and just kind of introduce score in places that I haven’t always felt comfortable doing.

But in this particular movie, placement was everything. In the car scene, I just withheld all the music because I thought it was all working. Overall, characteristically of this movie because it had at times a documentary style, I felt that subtle was way better than anything that started to feel movie-like. It took you out of it.

We tried it, and I had to go there in order to determine that as well — that certain scores just took over the scene and you weren’t playing with the raw emotion of what was unfolding — the “viscerality” of what was unfolding — that raw voyeurism. It just didn’t need music. That was a testament to how well those scenes were directed and acted.

HULLFISH: To the point about figuring out when to spot that music, at the end of that scene you do bring in music but it felt like the perfect moment. So how do you choose, “OK, I AM going to bring in music at the end of this scene, so now I need to choose the exact moment when it appears.”.

WILCOX: Glenn Close’s character says to JD, “You got to decide.” So we sit with that for a moment: what is this decision going to be? Are we going to hear it in the car? Is he going to say anything?

I didn’t want to back it up against that last line because then it felt too stingy. It felt like, “OK, now we’re really trying to drive this point home.” So I let it breathe for a second and let him think and then you start to hear the emotion of that music start to enter and creep into the scene as a pre-lap as we go into the next scene with adult JD and older Bev.

That particular song, “Tuesday’s Gone” is a song that JD heard when his grandfather passed, so it has some significance. It’s got me a little emotional talking about it. It’s not a randomly placed song.

HULLFISH: Oh interesting.

I didn’t quite get that the grandfather was living someplace else. And the audience doesn’t need to know that, right? Once I figured out that the grandfather isn’t living with the grandmother I thought, “Oh yeah. There was that scene earlier where he drives down the street when they’re all dropping off the luggage.”

WILCOX: They had an estranged relationship. But they lived in the same neighborhood. They lived very close to each other and remained in their children and grandchildren’s lives.

It’s funny that you talk about that moment because I was never certain that that moment landed until we took it to screenings and preview. At that point, I was certain that the audience understood it. The grandfather says to a Mamaw, “I’ll see you tomorrow” and you think that he’s gonna drive off like 20 miles to his place and he goes right down the street and drops his daughter off who lived down the street, and then he goes down four doors down to HIS place.

It wasn’t really fully until we previewed it that I heard a big laugh from the audience that I thought, “OK. We’re good.”

HULLFISH: It’s an autobiographical film. As the author, the book chose its moments. You don’t know EVERYTHING about this guy’s life. These are incidents that reveal something. Then the screenplay has to FURTHER condense the book into even fewer moments — more critical moments.

Was there anything that was in the script that you guys had to drop in post?

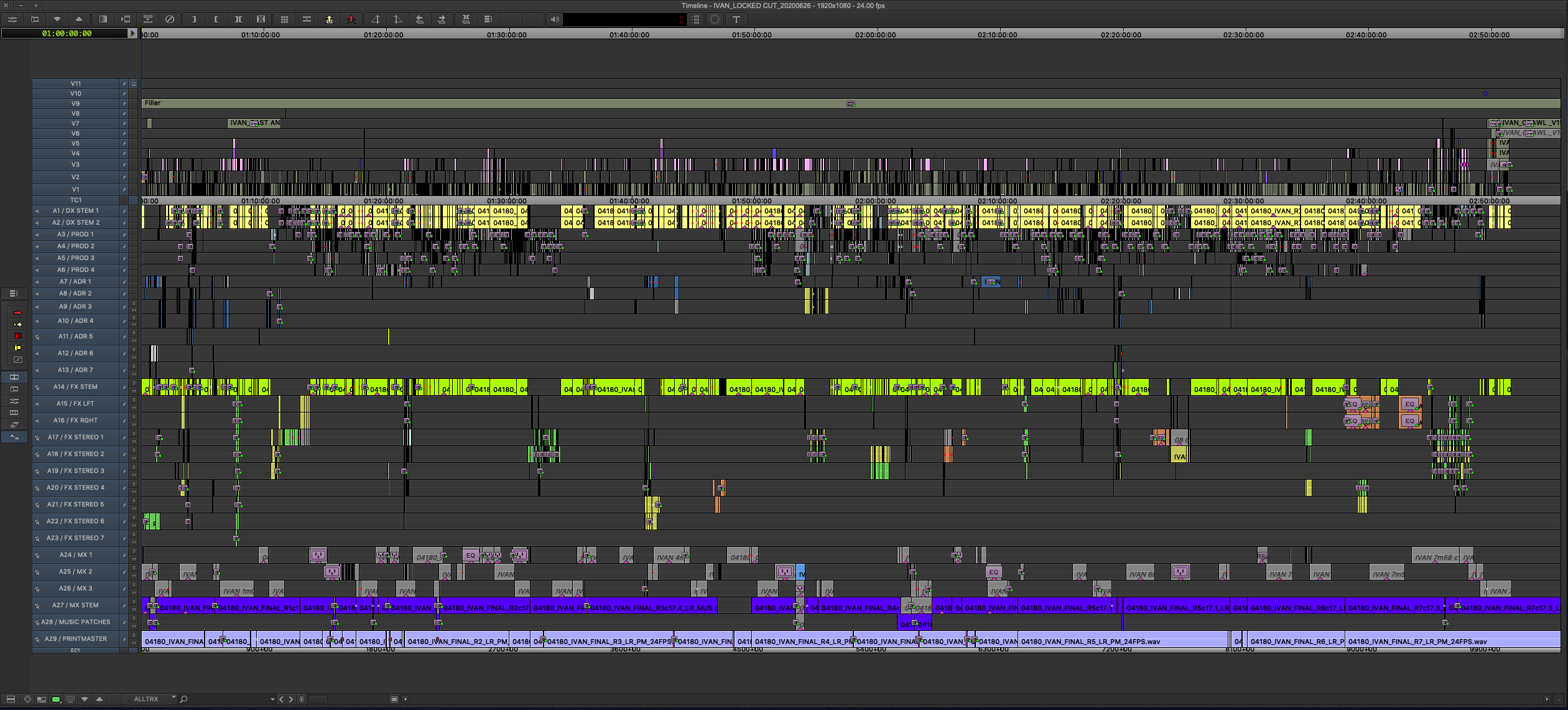

WILCOX: My cut was two and a half hours long. The movie now plays at an hour and 56 minutes. There were some great scenes and some great performances that we had to get rid of. It wasn’t that the scenes didn’t play or the performances were poor. It was a tonnage thing. We were making such strong points with what remained in the movie that the scenes that we took out — we could justify not needing them.

There was a wonderful scene where Bev came home from rehab and the family’s waiting for her to arrive because there’s a lot of hope with people when they go into rehab and come back home that this is gonna be the time that they make it. This is going to be the time that they turn the corner.

So that hope never subsided with the family and particularly with JD who had done all this work to prepare this three bean casserole and even burnt it once and then he came back and did it again — all in anticipation of his mom coming home.

He’s looking out the window. He sees the car pull up with her boyfriend Matt. They had banners and everything. It was just a wonderful welcoming home scene, but as the scene unfolded and they sat down for dinner Bev had picked up chicken along the way and was eating the chicken because she said the food was terrible in the rehab place.

She didn’t know that JD had been slaving over the stove to make the three-bean casserole and she’s not eating it. Glenn Close’s character tries to get her to eat the casserole and she takes some bites of it, but something in Bev just clicks where she starts getting angry and upset at Matt. And as the dinner unfolds it starts to unravel where she’s really starting to argue with Matt and then after dinner they have a massive argument.

She starts to leave to go out, just after she got home, and Matt’s asking, “Aren’t you going to stay home and hang out with the family a little bit?” He thinks that she’s cheating on him. It was a fantastic scene but we just couldn’t use it because we understood that Bev had issues and we understood how those issues played out. So we just couldn’t use it.

There were a number of scenes with JD — once he had been left on his own because his mom was in rehab and his grandmother was living on her own. There were a lot of scenes with him and just his dog that we had to get rid of. There were some really great scenes that we ended up leaving on the cutting room floor, but I have to say that I personally liked them and missed them.

There was another wonderful scene that Ron loved with the grandfather who had set up a secret phone in a toy chest to tell the kids early on if your mother ever goes nuts again — if she gets in trouble and you guys feel in danger — you pick up his phone and you call us. It was a wonderful scene.

I think in the structure of the movie, it came later rather than earlier to set up that kind of incendiary behavior from Bev. We left it in for a long time and it was probably the final scene that was cut out of the movie. Your gain story momentum that way.

So we ended up having to let go of some precious scenes.

HULLFISH: I believe it. What do you temp with?

WILCOX: This goes back to the research phase when I first got the job and I started talking to a lot of other filmmakers that had done documentaries on the hillbilly region and like musically what they had used themselves. What was cliche about the region?

Appalachia is like eleven, twelve states — but particularly in that Kentucky, West Virginia area — they are very sensitive to how the banjo is portrayed. They still hurt from the movie Deliverance. The characterization of the people who live in that region.

So early on I understood that banjo would not be great for this culture. So I started looking at some documentaries and talking to other filmmakers who did documentaries, and I came across a couple of docs. One Netflix doc called Heroin. That was about the opioid crisis. The composer is Daniel Hart. Through his music, I got turned on to other composers, but I temped with a lot of his stuff. Also, Johann Johansson — for accent and layer pieces. Those were my primary go-tos.

Daniel understood — because he was doing documentaries — how to NOT heavily, musically, sway the story one way or the other. And so I used that.

And then when Hans Zimmer came on board and we were doing our first music spotting, he was sitting in his office in Santa Monica and I was sitting in mine in New York and we were waiting for Ron and Brian Grazer and some other execs to show up for the spotting session and he says to me, “James. Who did the temp?” And I paused for a second because — it’s the great Hans Zimmer!

HULLFISH: (Laughs)

WILCOX: Oh, this could go down either path: this could be great or this could be really bad because he’s thinking I’m completely off. I’ve ill-toned this movie. And what was I thinking? He’s got a lot of work ahead of him.

After I told him, “Hans. I did the music.” He said, “It’s frustratingly good.” From that point on it was the Hans and James show!

HULLFISH: That’s awesome! I love hearing that.

There’s a long phone conversation during a road trip. That could go any way. The things that you see out the window. The parts of the conversation you choose to include. It’s like an eight-hour phone conversation condensed to two minutes. How did you construct that?

WILCOX: That was a toughie. Number one it’s the end of the movie and without giving away anything, there’s a cathartic moment that has to happen with JD Vance. The movie’s all boiled down to that.

We shot it using green screen and plates and LED projection but the actual dialogue part of it was a series of anecdotal stories as JD is beginning to share some of his life with his girlfriend. And he’s opening up.

There was much more there: moments that were reflected earlier in the film, he talked about his mom and how he learned to play football, and what his grandmother taught him and things about his grandfather, and then his girlfriend is relating stories about her upbringing.

So they were these two outsiders at Yale who bonded because of their different backgrounds. She’s of Indian descent. He’s from Appalachia. So they connected. Their unusual backgrounds really connected them well. And there were a lot more anecdotal stories, but at the end of the day what we felt was most earned and felt right at the end of the movie is what’s in there.

And we “broke” that. It was all storyboarded. I started out cutting storyboards and then I started getting green-screen and then I cut storyboards with the green screen and then we got the plates and then we started marrying the plates. It was actually blue-screen not green-screen. We had to go in and add a bunch of reflections and color timing it properly. Where is he now?

It was carefully researched because when you look at that whole driving sequence, he covers a lot of ground in going from Ohio back to Connecticut. So we had to sit down and map out his route. Do signage to show where he is now.

In some of the conversations she wants to know where he’s at, and he’s on the clock. He has to get back to Connecticut by a certain time. So all of that was very carefully thought out. There were parts of it that Ron liked a lot; parts I liked a lot; some that the producers favored. But we ended up asking, “What do we need to tell the audience? What’s most important?” Because we all have favorites in there. A lot of the favorites had to go.

The actor Gabe Basso was tremendous. His choices of what he did with that scene were great. He actually blew everybody away because there was something in him that also related to that particular moment that led to his performance. What was on paper and what he gave us are canyons apart,

HULLFISH: To get the audience to have the right emotion by the time he gets home — that’s the key.

WILCOX: You’re absolutely right. In screenings, we had a version of the film where he basically went back and got the interview and that was the end of the film. There was some voice over there and that kind of wrapped it up, but it was unsatisfying. It felt more like a stop rather than an ending.

So when we were testing the movie, we tested that as well. We arrived at the conclusion that “we need a scene here.” So we went back and did some additional photography and picked that scene up and everybody was happy.

The film has this in its favor: there are so many points of connection that are so relatable, and that’s one of them that is extremely relatable. He’s in this relationship and he’s figured out some things about the relationship that he wants to invest greatly in it and it affects and informs his performance and the information that he wants to come forth with.

The film has this in its favor: there are so many points of connection that are so relatable, and that’s one of them that is extremely relatable. He’s in this relationship and he’s figured out some things about the relationship that he wants to invest greatly in it and it affects and informs his performance and the information that he wants to come forth with.

I think a lot of people in relationships feel that they may be judged and how much of your background do you share and when do you share that? And if you share it, will the person that you love run for the hills? Or will they say, “I’m 100% in?”

HULLFISH: James It was a pleasure talking to you. This film is just beautiful. I hope everybody gets a chance to watch it and I’m sticking by my two Oscar wins for the leading ladies, if no one else. Man. What great performances you had to work with and great direction as well.

WILCOX: Thank you so much, Steve. I’m really honored to be part of your series — Art of the Cut. I was listening to it a lot when I was cutting this film. I listened to Tom Eagles when he was on his way to the Eddies for Jojo Rabbit.

Actually, I’ve never met Mike Hill, but I read your interview with Mike when I needed to take a little time away from the screen and stop and just do something else to take my mind away from a problem that I was trying to solve in the cut.

HULLFISH: Thank you so much. I really appreciate it. And I hope you and I get a chance to meet in person someday.

WILCOX: We will. That’s a bet. I definitely look forward to our paths crossing.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed, and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now