Joe Klotz, ACE has had a feature film and TV career that has spanned more than two decades. He was nominated for a 2010 Oscar for his editing of the film, Precious. His other work includes, Shelter Island, Rabbit Hole, The Paperboy, Lee Daniels’ The Butler, and Yellow Birds, among others.

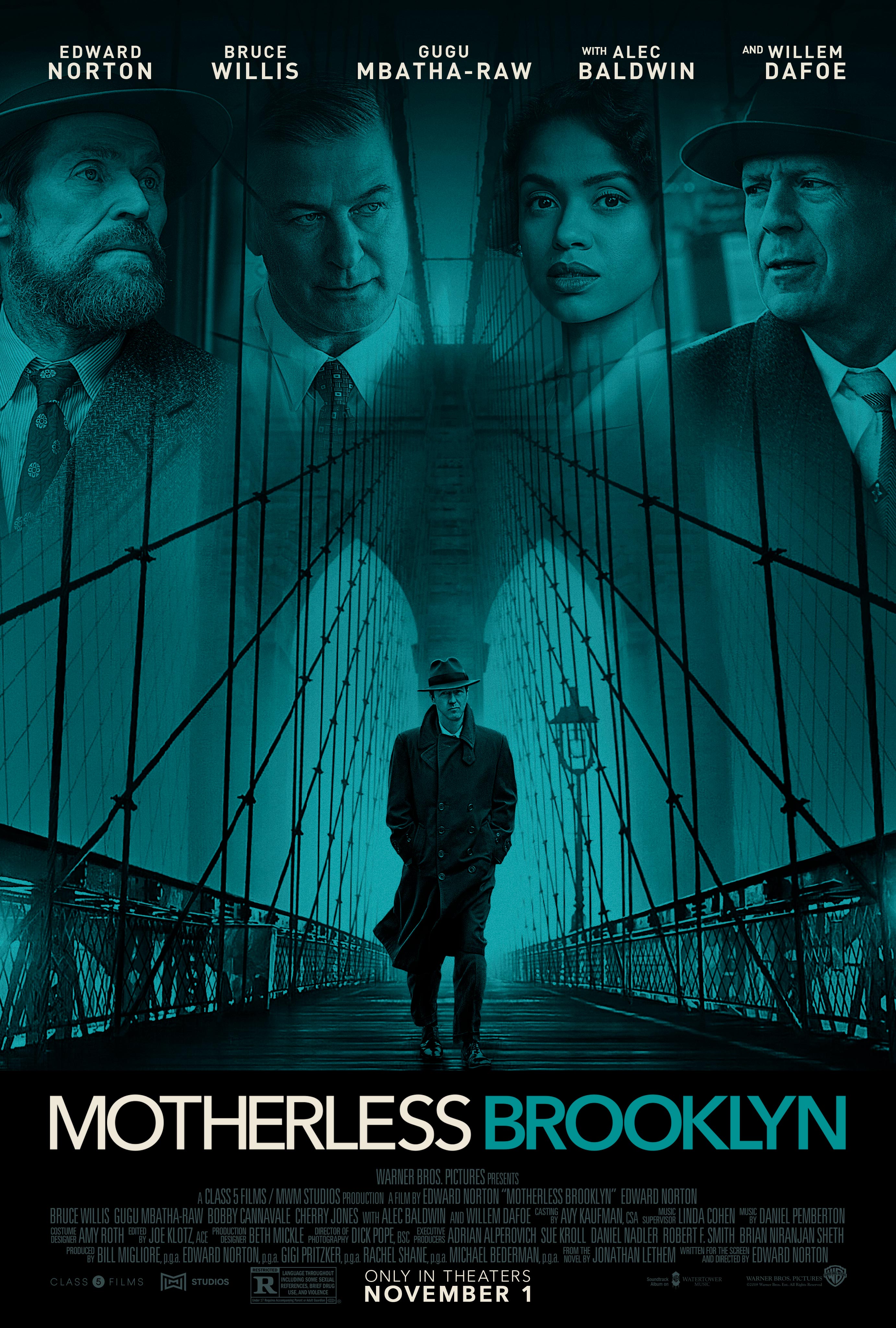

Today our discussion centers on the film Motherless Brooklyn, which Edward Norton, wrote, directed, and stars in.

This interview is also available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: Joe, we have a mutual acquaintance. I’m about to hop on the phone with (one of your producers) about one of my personal projects I’m trying to get made.

KLOTZ: Oh. She’s great. I worked with her on this and on Rabbit Hole.

HULLFISH: You hadn’t worked with Ed Norton before as a director, right? So is that how you got this job?

KLOTZ: No. I had not worked with Edward before. The way I got the job sort of starts with reading the book 10 years ago. And I love the book. It sort of takes place in the neighborhood I live in Brooklyn. It’s set in the year that I actually moved into the neighborhood as well. My friend Bill Migliori who is Edward’s producing partner produced the very first film that I worked on. We went to Sundance with that. So I proceeded to get in touch with him and then hound him over the years saying, “If this ever gets the green light, give me a shout, because I love the book and I’d like to have a meeting with Edward.”

There’s a funny side note to this. I asked about it several times, because he was developing the script for a good 20 years. And then one day my wife called me and said, “You’ll never guess what just happened.” And I said, “What?”

A location manager called me about a film that’s looking for a living room in the Brooklyn neighborhood, and in walks Edward Norton and Bill Migliori and she knew Bill.

Bill was petting my dog and comes up and says, “Oh my god! Giselle! Hello! How are you doing?” Anyway, it was a lovefest because we were quite tight. He said, “Hey, how’s Joe?” And she proceeded to say, “Well, he just finished a job and he’s available.” She was trying to get me the job.

HULLFISH: Trying to get you out of the house?

HULLFISH: Trying to get you out of the house?

KLOTZ: Trying to rent the house for a film shoot AND get me out of the house.

HULLFISH: What do you think of your work that Edward saw, or do you think it was that personal connection?

KLOTZ: I think it was first the personal connection with the producer. For him to suggest me to Edward. And then I know he did watch a couple of my films — whether he had seen them or did some research — but I do think it was Precious, to tell you the truth because he mentioned that in our first and only interview.

Then when we were cutting he brought that up several times as far as how we got into her head and into these fantasies and flashbacks that run through Precious. There is a similarity there because of Lionel’s character (played by Edward Norton) — we go into his head and the way he is processing all that he’s going through with his Tourette’s and his obsessive compulsiveness and there are flashbacks. They’re different obviously, but how we dip in and out of someone’s mind basically is the same.

HULLFISH: The last released film that I edited was with a director-writer-actor so I just wanted to talk about that, since Norton directed, wrote and acted in this. Is there a danger that someone who is that involved is somehow overly precious with his writing or acting or directing? How are they judging their performance? How do they distance themselves somehow? How do you have to help with that?

KLOTZ: I was a bit worried about that myself. The film I had mentioned earlier that Bill Migliori produced had a similar thing with a writer-star and his brother directed.

It’s a little unnerving at first but Edward was quite gracious and open to my input on that. I held back a little bit at first, and we just sort of ended up talking about Lionel — his character — in the third person. So it wasn’t like “Hey, I think it’d be better if YOU had done this.” It’s more like, “Hey, I like the way Lionel does this.” It just became very easy and there was zero vanity and just all like serving the film, serving the character and it was a pretty fun and easy collaboration.

It’s a little unnerving at first but Edward was quite gracious and open to my input on that. I held back a little bit at first, and we just sort of ended up talking about Lionel — his character — in the third person. So it wasn’t like “Hey, I think it’d be better if YOU had done this.” It’s more like, “Hey, I like the way Lionel does this.” It just became very easy and there was zero vanity and just all like serving the film, serving the character and it was a pretty fun and easy collaboration.

Obviously, when you work with a director for the first time it’s a process. You get to know each other and there’s a little trepidation at first about how much you want to throw in there and at what time and then by the end you’re just firing on all cylinders and collaborating and trying to do the best for the film.

HULLFISH: Did his Tourette’s cause difficulties with continuity at all?

KLOTZ: With his verbal tics and outbursts there really wasn’t anything different than normal continuity. He did mix it up a little bit. He didn’t want it just to be all over the place, so he had his sort of go-to reactions — and there was a consistency there — although there was quite a bit of variety, so that wasn’t the problem.

There was a small bit that was a bit hard to deal with on occasion which was a physical manifestation of his affliction — which was he would tap a character once and then tap twice and then tap three times. It was established that he did that and that took a certain amount of time to go through that little ritual and we didn’t want to truncate that because it needed to be “the one, the two, and the three” There was fun and charm in that, as well as him struggling to not invade other people’s personal space, because he knew it was wrong. It was pretty consistent that he did it while he was saying the same line so you could cut between things and stuff like, so it was a little bit limiting, but it wasn’t that hard. There were a couple of times — if you look closely — where we didn’t let him do the full run on that, but you get away with stuff like that.

HULLFISH: I didn’t notice. Tell me about the narration. Did that change from the script? How were you scratching? Was Ed scratching for you while you were in the room?

KLOTZ: Well the shocker of that is that the original script had no voiceover in it.

HULLFISH: WHAT??

KLOTZ: We cut the film without voiceover, and it worked pretty well as far as we were concerned but we thought there was a little bit of distance to our main character — a little bit of a reserve — a little space between the audience and him.

So Edward said, “I’ve been holding this in my back pocket. Let’s start playing with this (narration).” Voiceover is sort of a familiar trope in film noir as well — not all the time — but it’s not out of the norm. I was sort of into it, too. A lot of times films that don’t start with voiceover lean on voiceover to fix problems, but I think this helped us elevate the connection between the audience and the character and it had a nice arc where it was a little bit reserved in his performance at the beginning and as you go through the film it gets a little bit more personal and a little bit warmer.

It was brilliant and fun to be in that room with a mic stand and Edward would run through what he was thinking and then we would just record and he would sort of stroll around the room — sort of getting into character with a whole lot of concentration and intensity — and come up to the mic and and he’d say, “Are you’re rolling?” And I would just give him a little nod so as not to break his concentration and he’d go for it.

In the beginning, I didn’t say anything. Then as we went through weeks and weeks of this, I’d say, I really liked when Lionel did this little thing — I didn’t give him direction by any stretch of the imagination — but participated in what I thought worked and then we’d try to cut it in and then we’d say, “Yeah, that’s not fitting just right and the words need to be tweaked a bit” and he’d go back for it.

In the beginning, I didn’t say anything. Then as we went through weeks and weeks of this, I’d say, I really liked when Lionel did this little thing — I didn’t give him direction by any stretch of the imagination — but participated in what I thought worked and then we’d try to cut it in and then we’d say, “Yeah, that’s not fitting just right and the words need to be tweaked a bit” and he’d go back for it.

That, I think, is a failing for a lot of films when you say, “OK, we’re gonna do voiceover” and you temp your voice in or if it’s a woman you grab somebody in the office and they temp it and then you time everything out and maybe the actor scratches it on an iPhone and sends it to you, but then it is recorded later and put in. And I think that’s a failing, because I think the intimacy of voiceover In a movie just needs to work it over and over again, as far as the writing and as far as the performance. And just going into a booth for a few hours and knocking it out — I don’t really think that does the film much good.

That’s what we did with Precious as well. Gabourey Sidibe came into that edit room — we were cutting in Manhattan, she lived in Manhattan — she would come three, four times a week over the course of a few months and Lee (director Lee Daniels) was writing and she was performing and he was pushing her. In that film she goes from sort of uneducated and then as she goes through school, she progressed to being much more eloquent, so that had to be finely tuned. It was a “scratch” because she’s doing it in the edit room.

We were in the Brill Building, right on Broadway, and I have a mic that I got at a yard sale and buses are going by and they’re recorded. That’s in the film because she never matched it and Lee tried and he said, “We’re just going to go with what we recorded in the edit room.” For most of it.

I’m working on a film now and we’re scheduling the voiceover and I was trying to ask for it not to just be done in a day, but contractually that might be the way it is.

HULLFISH: Two things about narration before we move on. You mentioned that Edward kind of walked around the room then strode up to the mic… was it scripted? Did he write it down or perform it out of his head?

HULLFISH: Two things about narration before we move on. You mentioned that Edward kind of walked around the room then strode up to the mic… was it scripted? Did he write it down or perform it out of his head?

KLOTZ: A bit of both. He definitely worked it out ahead of time. But he definitely created on the spot as well. He’d be in character and say the line and it wouldn’t feel right and he would turn the phrase and sometimes look at me and I give a thumbs up or whatever — I was trying to support him when it sounded right. It was great. It was a lot of fun to see that come alive.

HULLFISH: Did you see Ad Astra?

KLOTZ: I did.

HULLFISH: That was originally written and edited without narration which shocked me. It’s interesting that both these movies were originally without narration. Very interesting.

Let’s talk about temp. There was a lot of great jazz in there.

KLOTZ: Obviously he had Wynton Marsalis there to help him curate what was going to be played at the club and that was all obviously sourced out and recorded well beforehand, but as far as temp goes, he really didn’t want to lean on a jazz score. We are both big fans of Radiohead and Thom Yorke and Jonny Greenwood and so we temped with a lot of that.

There Will be Blood and just a lot of some of the more obscure discordant tonal stuff of Radiohead to give it the right mood. I could go back to my Spotify list — I’ve got Daniel Pemberton from five or six years ago. I’ve always been a fan of his. And when he was given the nod to come do this, it was quite exciting and then I started exploring some of his newer stuff. I think it was For all the Money in the World — I used a lot of that to temp.

Probably composers hate that — when you temp with score from another of their movies into the current movie — because it’s like, “Excuse me! I want to do something different.” But it really worked for some of the more tense things, like the race up to Harlem to save Laura. I temped with that music.

Probably composers hate that — when you temp with score from another of their movies into the current movie — because it’s like, “Excuse me! I want to do something different.” But it really worked for some of the more tense things, like the race up to Harlem to save Laura. I temped with that music.

Then Edward went to London and worked with him and I thought they really knocked it out of the park. I really loved that score.

HULLFISH: It’s interesting that you say that composers don’t want you to temp with their previous score. For the film I just did, we got all the composer’s old music and I tried to only temp with stuff from that composer.

KLOTZ: What did they have to say about that?

HULLFISH: They definitely did something different from the temp, but I think they were just happy that they didn’t have to try to match some John Williams temp!

KLOTZ: That’s a good point.

HULLFISH: There’s a great sequence where Lionel is high. It transitions into a shot of Alec Baldwin swimming. Was there a trick to getting that transition right from dream to reality?

KLOTZ: It was scripted and planned out but it completely evolved. He smokes some opium, I believe and falls back into water and he’s sinking into forgetting about the tragedy that just happened and up through that water we see somebody up above him as he sinks to the bottom. And there was just a simple shot of one body-double swimmer swimming through the frame and it just had a few frames when he was in the frame completely by himself, and we wanted that to last, so we pushed it back and we got our visual effects supervisor, Mark Russell, involved early on and did some looping and pushing the swimmer from left to right. They tried many different visual effects there and sort of settled on this kaleidoscopic mash-up and just let the sound sort of pull us out of that reverie and into the reality of the shot of Mr. Big — Moses Randolph — swimming in the pool.

KLOTZ: It was scripted and planned out but it completely evolved. He smokes some opium, I believe and falls back into water and he’s sinking into forgetting about the tragedy that just happened and up through that water we see somebody up above him as he sinks to the bottom. And there was just a simple shot of one body-double swimmer swimming through the frame and it just had a few frames when he was in the frame completely by himself, and we wanted that to last, so we pushed it back and we got our visual effects supervisor, Mark Russell, involved early on and did some looping and pushing the swimmer from left to right. They tried many different visual effects there and sort of settled on this kaleidoscopic mash-up and just let the sound sort of pull us out of that reverie and into the reality of the shot of Mr. Big — Moses Randolph — swimming in the pool.

HULLFISH: It seemed like the timing of that transition from the sinking to swimming would be critical.

KLOTZ: The timing — sometimes the footage dictates what the timing is going to be, because as he falls back, we didn’t want to have him flailing, so there was just a certain amount of time where he was sort of doing this more ethereal freefall, so that sort of dictated what worked and we slowed it down a little bit. There were a couple of angles from above and below and just kind of worked it as much as it could be worked.

HULLFISH: There’s a scene where Lionel is working the car service phones where you made some great use of jump cuts. Can you talk about that? Was that the first place there were jump cuts in the movie?

KLOTZ: I believe so. Yeah, I’m pretty sure that was it.

There were some other places where we were sort of in his head — voice-over-wise and thought-wise. I love a good jump-cut scene. He’s processing what he heard in that original scene. I don’t think the jumpcuts come out of the blue in that there are some other stylistic things that happened beforehand — i.e. the scene where he’s on the phone listening in on the meeting with Frank, his boss, that turns sour. That’s shot very obliquely with shadows and out-of-focus and odd framing.

He’s on the phone and he’s listening, so we’re trying to portray what he’s hearing and how he’s perceiving that — which is, Frank, his boss is pretty sharp and focused because he knows him, but he doesn’t know the other characters that are around him in that room because he’s not there he’s only hearing it — so you’re in his mind and he’s trying to bring them into focus so his obsessive-compulsive mind can remember it and live it. That was cut fairly jumpy.

Getting back to the jump cuts you mentioned, he’s processing what he heard, which is the word “Formosa.” And he’s just trying to figure out what that means and breaking it down in all different ways and obviously to let him do that in one fell swoop would have probably been about 45 seconds of writing, so jumping it and having him mumble and having some good music there let us feel how his fragmented mind is processing that information. So that’s what the thought was behind that.

HULLFISH: You mentioned flashbacks earlier. Tell me a little bit about how you cut those flashback sequences. There’s a shooting early in the movie, and then Lionel’s character remembers that shooting throughout the movie. Did you do some temp color grading of that stuff in the Avid as you were editing — giving it that flashback look?

HULLFISH: You mentioned flashbacks earlier. Tell me a little bit about how you cut those flashback sequences. There’s a shooting early in the movie, and then Lionel’s character remembers that shooting throughout the movie. Did you do some temp color grading of that stuff in the Avid as you were editing — giving it that flashback look?

KLOTZ: Edward said he wanted it to appear like Lionel is trying to piece together what happened in that shooting, and so he basically rewinds. So, up to that point, we rewind what transpired in that sequence and then he starts playing it forward and back and forward and back and very fragmented.

The color was a small part of it, I think.

HULLFISH: Of course, it was the actual editing.

KLOTZ: What I did was I just sort of edited the sequence in a pretty fragmented but inclusive way of all that happened and then said to my assistant, Beth Moran, and our apprentice, “Can you figure out how I can scrub full frame on the Avid and record it at the same time and then put it back in the Avid so I can edit what we’re recording?” So they figured out a way to capture that and I just went in when they had it all set up and just played it and scrubbed it forward fast and stopped and back and forth 15 times and created about 20 minutes of footage — real herky-jerky then landing on specific freezes of Frank Minna’s face or just as the gun went off and then took all that footage and edited that to be part of this flashback and desaturated it and added some color and stuff like that.

HULLFISH: I only saw it once… I’m assuming there was a bunch of sound design to those flashbacks?

KLOTZ: I’ve only seen it one time in the last year. I finished at Christmas time last year and I’ve only seen it once since then. I’m trying to remember it all. Supervising Sound Editor Paul Hsu just did an amazing job. There’s some rewind stuff and the guns echoing and there are sounds from the moment. He did a really great job with that.

KLOTZ: I’ve only seen it one time in the last year. I finished at Christmas time last year and I’ve only seen it once since then. I’m trying to remember it all. Supervising Sound Editor Paul Hsu just did an amazing job. There’s some rewind stuff and the guns echoing and there are sounds from the moment. He did a really great job with that.

HULLFISH: As in many movies, there are many places where the score bridges two scenes or more. When you’re cutting an assembly, are you cutting in temp? Or are you waiting for those scenes to be joined before you put in temp? How does it work on those scenes where score crosses?

KLOTZ: It’s weird. I wouldn’t say it’s arbitrary, but sometimes I just get this feeling like I don’t want to put temp in. I want to make it work without leaning on that crutch. And then I love music so much that that’s really hard to hold back, you know? Obviously, if you choose the right piece of music it can elevate a scene. I’ll choose something for a scene that needs it and if there is a moment where it feels organic — like it could come out before the scene ends — then I do that, and if it doesn’t, I just let it cut out or trail out until the glue between those two scenes — there might be a transition shot that I don’t have yet that you can let that music dissipate through and have a clean palette when you come to the new scene or sometimes that music is just the right piece of music to take you into the next scene.

So it really is obviously on a case-by-case basis but it’s a really great question. I’m working on a movie now that has a lot of music and it’s a lot of fun when it works and it’s a pain when it doesn’t, like there’s a great song that is kicking off the next scene but how do I get out of the music of the previous scene and it can be a conundrum, but it’s a fun one.

I’ve been at this for a while and I’m really kind of enjoying doing some temp music editing and feeling proud of myself and then I hear it with an audience and think, “Oh my god! What have I done?” And then getting it to a real music editor.

I’ve been at this for a while and I’m really kind of enjoying doing some temp music editing and feeling proud of myself and then I hear it with an audience and think, “Oh my god! What have I done?” And then getting it to a real music editor.

There actually is a fun story: Thom Yorke (of Radiohead) wrote an original song for the film that we had before the movie was shot called Daily Battles and it’s the song that is used when Lionel is walking home after Frank has died and it’s right previous to the scene where he smokes some dope and falls into the water. It’s a real sad lament as he walks through the streets of Brooklyn, and so we had that song and I cut that whole trip back to his apartment where he cries on the stairs and everything and it was all set to Thom Yorke’s song and in timing it out I could not make a good music edit to make it work, and we needed it to land at a certain place. So I did a pretty slop edit and then Edward said, Radiohead’s in town and Thom Yorke is gonna come by and I want to show him that scene, so it’s like, “Oh no!” I stayed late and worked on it and I got it better, but… So Thom Yorke came in — and I’m a big fan — I went to see them when their very first album came out back 20 years ago — but I had to play that scene for him and I put a caveat out there. I said, There’s a very mediocre or bad music edit in there and he was very gracious and eventually, we got a professional to do that for the final.

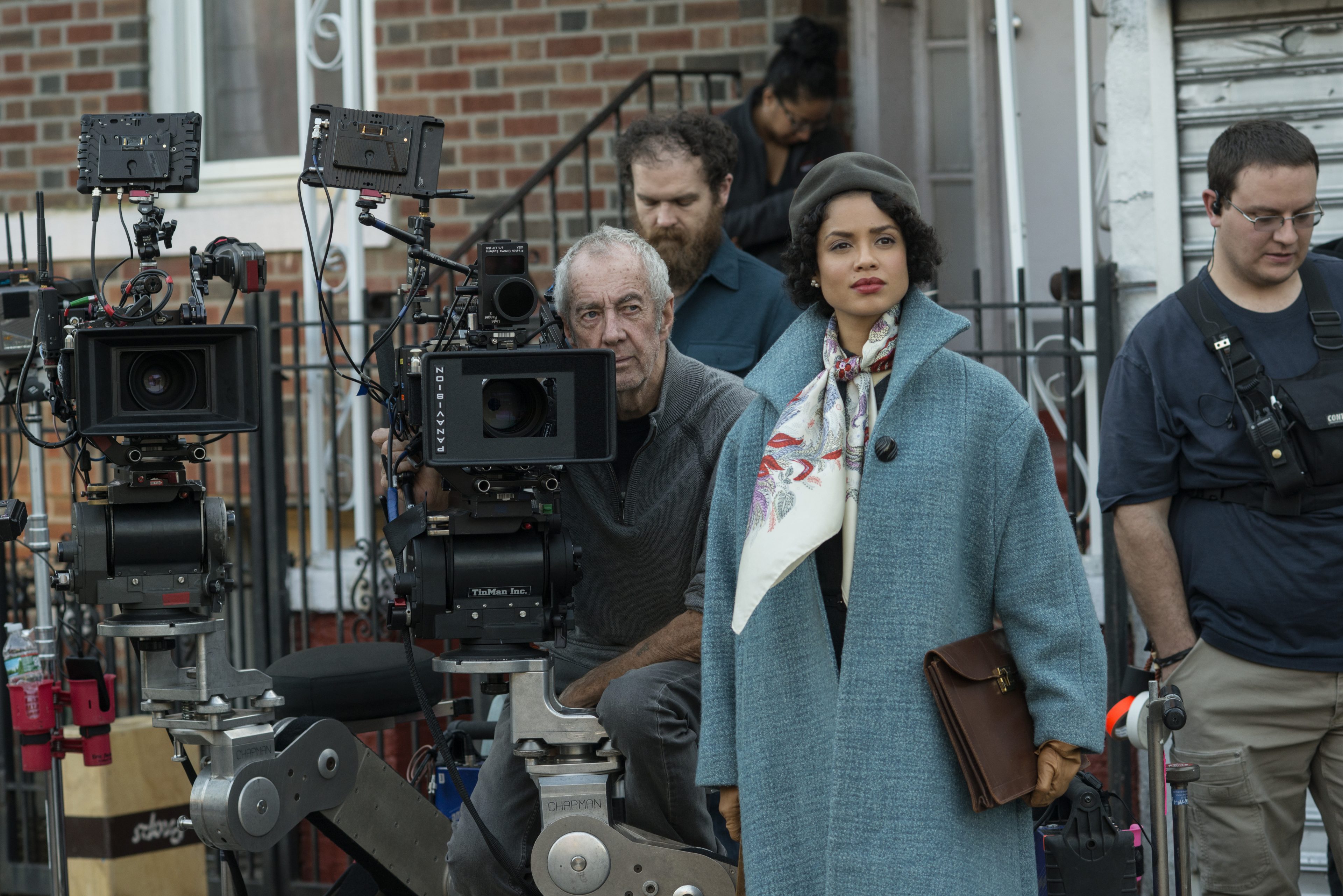

HULLFISH: This film is so gorgeous. Every single frame. Were you just bowled over when you started getting dailies in?

HULLFISH: This film is so gorgeous. Every single frame. Were you just bowled over when you started getting dailies in?

KLOTZ: Yes eventually. But the first couple of scenes were rough ones — like the scene with Frank up in the meeting with the corrupt government officials. And when I was looking at that stuff, I was thinking, “What is this?” It’s a three-minute scene of all this oblique out-of-focus stuff. “This is gorgeous, but I have no idea what I’m gonna do with this.”

But, yeah, just day-in and day-out of this gorgeous footage of New York that Dick Pope nailed. It was a really fun mix of streets and locations and studio work and it evolved too. He did so much with the color correct. It was fun to see that come to life as a 50s tableau because they found great locations but there was a lot of visual work to be done. It’s great to cut a movie where there a big chase on a bridge and then later that night I’m leaving town going over the same bridge with my family to get away for the weekend, so I was feeling very connected to New York and enjoying that process.

HULLFISH: On the subject of dailies — you mentioned the difficulty of that phone call scene — how do you watch dailies? Do you watch them very actively — putting locators or sub-clipping or creating a selects reel or are you letting it wash over you?

KLOTZ: I have a process that I don’t know how it developed. Maybe just doing independent films that were under-the-gun and time frame. It’s a bit unorthodox in that in the early days when you’d have this paralysis when you come to a scene, like, “What to do? Where’s my first edit coming from?”

So my trick was: OK, here’s a circled take that’s a medium or a wide and I’ll see all that they’re going for, and I just lay that down. That’s the first thing I do. I don’t even look at the dailies I just pick one of those things and play it down and if there’s a break in it, I’ll just cut it together or I’ll choose another take that’s seamless. And then I just start at the beginning and watch the first set-up and I don’t really take notes.

I just watch and if something hits me — if I feel something like, “Oh my God. That’s a perfect acting moment or that little look is great” — I try to go with that initial very first reaction with my gut that moves me; that hits me; that excites me. And I cut that in. Here’s a big wide shot and there are three close-ups in it. And then I take the next take and then the next take and it’s a little bit fragmented and a little bit disjointed but I know where I’m going to go. I’m not making edits that are smooth or anything, that’s how I start cutting the scene.

I’ve tried it before where I take notes and I don’t want to be looking at a piece of paper or a computer screen with notes, I want to be looking at the footage and really preserve that initial reaction.

I’ve tried it before where I take notes and I don’t want to be looking at a piece of paper or a computer screen with notes, I want to be looking at the footage and really preserve that initial reaction.

It’s a little bit cumbersome. Sometimes you miss a connection, but if I really like two things, I won’t throw away one thing. I will stack it or sometimes even in the script there’ll be a line I’ll just write “take three” and write down the time code as “great alt.” So that’s basically how I do it.

HULLFISH: I’m going to have to try that method. It’s almost like doing a selects reel, but you’re using a master shot as a placeholder for the timeline.

KLOTZ: Yes it’s a template basically.

HULLFISH: In the jazz club sequence can you talk about the challenge editing music that appears to be playing live while characters are actually reacting to it? It’s one thing if you’ve got a band in the background that they’re not really reacting to, but this was very interactive with the music so the music couldn’t just be dropped in.

KLOTZ: It was a little daunting at first. “How am I gonna do this?” But they prepped it really well. Basically, in the jazz club there are three songs: one blues walk where they just sort of come in and the band goes to the stage and Lionel and Laura settle in to watch and they have a conversation while it’s going on, so I just cut the performance of the full song knowing pretty much that we weren’t going to use the whole song, but maybe close to it. And then on the dialogue side, there are certain bits of conversation that were interrupted by Lionel reacting to the music. So they had to be timed because his “Tourrette’s run” would be sort of like the run of the music. So a melody would be in the music and then he’d run that same series of notes verbally, so those had to be fit in at a certain place.

But the magic of that was they shot the band with four cameras and they shot that conversation and the subsequent songs as well with three cameras, so I had a lot of choices. So that worked out and there were also bits of their dialogue where they were playing the music so Edward could do those runs and be in sync. And then there were other times where they ran it without the music so the dialogue could be clean and I could insert it into the song wherever it worked.

But the magic of that was they shot the band with four cameras and they shot that conversation and the subsequent songs as well with three cameras, so I had a lot of choices. So that worked out and there were also bits of their dialogue where they were playing the music so Edward could do those runs and be in sync. And then there were other times where they ran it without the music so the dialogue could be clean and I could insert it into the song wherever it worked.

There were some things that weren’t tied to the music so I could be like, “OK, well, this is a little introductory thing that they say here and then the music could overwhelm them here and then he has a little interaction with Laura here.” So it was a lot of variety. There was stuff that was had to be sunk. And there was stuff that was looser that I could move around and place wherever it was needed to create that flow.

HULLFISH: Also, I love that ballad that the band plays and Laura and Lionel danced to. Was your approach to that scene cutting the music performance or cutting the performance of the actors and then dropping in the music?

KLOTZ: Yeah, exactly, because that was designed to almost be one shot, but to be on them to let that evolve in front of you, because they just met and to have that be really intimate so quickly I think had to be handled with kid gloves.

So, to start with, basically, I chose a take that really moved me and Edward obviously chose that take as well. And then dropped in some musical bits, like when the trumpet player throws it over to the piano player in a really soft moment, that really added to the mood of the moment.

First of all the song is actually the Thom Yorke song — Daily Battles — that is played earlier. Wynton Marsalis did a jazz arrangement of the Thom Yorke song so that theme threads through. But also, at that point, Laura’s uncle and his henchmen are watching them and wondering what’s going on between those two. So there was a fair amount to cut around to, but I was just trying to stay on them and let that intimacy grow as much as possible.

First of all the song is actually the Thom Yorke song — Daily Battles — that is played earlier. Wynton Marsalis did a jazz arrangement of the Thom Yorke song so that theme threads through. But also, at that point, Laura’s uncle and his henchmen are watching them and wondering what’s going on between those two. So there was a fair amount to cut around to, but I was just trying to stay on them and let that intimacy grow as much as possible.

HULLFISH: I’m always interested with special shots that are obviously more than just your typical coverage whether there IS coverage and how those kinds of things work. The scene that I want to talk about is when Gabby Horowitz is getting to the speech at the rally and a camera follows her out of a car, through a crowd and she arrives just as the speaker on the platform is introducing her. You’re listening to the speaker through the whole shot and it times out perfectly in the performance. Was there coverage? Did you just know, Oh my gosh! What a great shot. I just have to stick with this the whole time?

KLOTZ: I believe there was a little bit of coverage but that’s how that was designed to work in the film. And I love no special shots too. But only when they work. Sometimes when people do a special shot and it doesn’t work and they were relying on that and didn’t get coverage? You kind of get boxed in a corner. But that one really worked, because the car drives up, they jump out and it tracks with her to the podium and I love that kind of stuff where it’s not really obvious what’s happening. You’re hearing the sound of what’s happening. You’re hearing the other speaker. You’re not seeing the crowd, but you’re hearing it, and then she gets swept into it. You’re kind of with her. And I think that really pulls the audience into experiencing it the way you would want them to.

HULLFISH: It just felt very organic and wonderful.

HULLFISH: It just felt very organic and wonderful.

KLOTZ: Sometimes they get it right in production.

HULLFISH: Come on! We don’t have to save everything?

KLOTZ: Exactly. We like to think we do.

HULLFISH: I hesitate to say anything. I love the editing of this entire so much, but there’s a scene where Laura and Lionel are in bed and there was a cutaway that made me wonder how much coverage there was.

KLOTZ: I’m laughing because I know exactly what you’re talking about — there’s a very strange shot of a mirror — it sort of comes out of the blue.

We did not have a lot of cutaways. It’s been a year since I really delved into the film, but I do remember we had a really good reason to use that and why we couldn’t just go to a reverse of the other person.

(((SPOILER ALERT))))

But that scene evolved in a quite interesting way in that it follows on the heels of Laura’s uncle being killed. Then Lionel escorts Laura up to her apartment and it becomes romantic and they fall into bed and it’s the next morning and it’s alluded to that they had a romantic overnight.

But that scene evolved in a quite interesting way in that it follows on the heels of Laura’s uncle being killed. Then Lionel escorts Laura up to her apartment and it becomes romantic and they fall into bed and it’s the next morning and it’s alluded to that they had a romantic overnight.

(((END SPOILER ALERT))) That scene kind of bumped for some people. It bumped for me a little bit when I read the script. It’s a little bit awkward on the heels of a tragedy. We tried to make it work and tried to minimize it and just have it be as far off-screen as possible and in some test screenings, it still bumped. So basically that scene was reshot. But we could only reshoot half of it because the set had been struck.

So Laura’s side when you’re shooting over Edward’s shoulder to her that is from the original because basically what was changed was — a little bit of the dialogue — but it pretty much stayed the same, but what changed was on Edward’s side he was not shirtless under the covers. He was in his clothes on top of the covers. So it feels like she had asked him to stay because she was emotionally distraught and needed company. And it was a platonic stay.

So that’s how we recreated that. And then the stuff over his shoulder where you saw his shoulder they painted on a shirt. So it was a lot of machinations; a lot of prepping of what we needed. The scene was cut with what we were going to use on her side so we knew exactly what we needed on his side.

HULLFISH: I was going to say that it didn’t bump at all for me, but now I know why.

KLOTZ: We jump through some hoops on that one. I think Gugu (Laura) was in London. They flew the headboard to London and shot it over there.

KLOTZ: We jump through some hoops on that one. I think Gugu (Laura) was in London. They flew the headboard to London and shot it over there.

HULLFISH: On another topic, you’ve worked with Lee Daniels on several films. How did that relationship start and how is it different working with a director that you’ve worked with numerous times compared to a first-time relationship?

KLOTZ: Well, there was a first time with Lee as well. I interviewed for that movie after some of it had been shot and I think I got that job because he showed me some dailies of Mo’Nique and I said that’s a nomination for Best Supporting Actress and he said, “Really?” And then she went on to win. So we didn’t mess that one up.

Working with Lee was a lot of fun. And it was hard too. But he was great. He said a couple of things to me at the beginning that I’ll never forget which were: “Don’t edit yourself. Give me the most bold, raw, outrageous — whatever you think works for the film.”

He said, “I will edit you.” And he said, “What I want you to do is: we’ll talk about the scenes and I’ll tell you where I want it to go and what my thoughts are, but I want you to bring what you can bring to it and I’ll let you go do that and then I’ll come back. But I want you to make me fall off this couch.” So I said, “OK. That’s a challenge.”

I didn’t make him fall off the couch too many times, but a couple of times he started leaning forward more and more and a couple of times he came off the couch. So it was nice to have that kind of collaboration. There was a lot of room to play and experiment and as happens with every director — Edward included — it’s good to get a little space to work out what they’re asking you to do. You talk about the film or scene and “this is what my intention was and this is how you cut it when you did your first pass while I was shooting, and I liked this but I think we should try something there” and then they go away and let you do that and then come back and take it through a couple more rounds with this and then as time goes on they’re just in the edit room more and more because you’re fine-tuning together and making bigger decisions.

I didn’t make him fall off the couch too many times, but a couple of times he started leaning forward more and more and a couple of times he came off the couch. So it was nice to have that kind of collaboration. There was a lot of room to play and experiment and as happens with every director — Edward included — it’s good to get a little space to work out what they’re asking you to do. You talk about the film or scene and “this is what my intention was and this is how you cut it when you did your first pass while I was shooting, and I liked this but I think we should try something there” and then they go away and let you do that and then come back and take it through a couple more rounds with this and then as time goes on they’re just in the edit room more and more because you’re fine-tuning together and making bigger decisions.

So that is my optimum and I had that with Lee’s style and I had that with Edward’s style too. When you start off with somebody new you’ve got to create a language and a trust. I just held back and made sure I understood what his intentions were with the film and where he wanted to take it and just figured out a way to help him take it there.

As we went further, he started trusting me and I could start putting myself into it more and helping him achieve that.

HULLFISH: Can you tell me about some of these scenes?

KLOTZ: Willem Dafoe at the diner. The challenge for that scene. I had such a blast working with Willem Dafoe. Alec Baldwin. Gugu. Bobby Cannavale.

That scene with Willem, he’s a pretty outrageous character. And that scene has a whole lot of exposition, so it was sort of a balance between making it fun; tightening it and making sure we included what was necessary to move the plot along; and reveal who he was: this tightly-wound, overzealous character who’s trying to achieve his own ends but also sort of help end the corruption of the city.

HULLFISH: Those scenes always make me think about where you play specific lines on or off the actor who is speaking.

KLOTZ: In general I go with my gut. Obviously you’re not going to just cut to who’s ever talking. So if somebody gives you something when they’re saying a line you make sure you keep that. And if somebody gives you something as a reaction to what that line is you go with that.

That married with when I’m in the overs and you can see the other person is or isn’t talking and when you go into the close up for a clean reaction shot or a clean pre-lap of the line? It’s just about creating flow and those little spaces between lines and those overlaps of lines.

I just think it just comes from doing it a lot.

I love a good argument too. It’s always fun to just work with: “Well, they were heated and they actually have overlapping lines or they didn’t and I’ve got to create them.” It’s always a fun day when you’re creating something really intense like that.

I had a blast with the whole race up to Harlem where he jumps in a cab knowing that the girl’s in danger. The fun with that was the variety of the pacing. This driving music and she’s getting off the subway and he’s telling the cabbie where to go — running up the stairs and then boom — silent, and there’s a moment and then it explodes again. I love doing that stuff. This film, besides working with Edward and having a blast with him, was working with great actors and great dialogue. It was a bit of a dream come true.

I had a blast with the whole race up to Harlem where he jumps in a cab knowing that the girl’s in danger. The fun with that was the variety of the pacing. This driving music and she’s getting off the subway and he’s telling the cabbie where to go — running up the stairs and then boom — silent, and there’s a moment and then it explodes again. I love doing that stuff. This film, besides working with Edward and having a blast with him, was working with great actors and great dialogue. It was a bit of a dream come true.

HULLFISH: What do you think got you the Oscar nomination for Precious?

KLOTZ: Well that’s a tough question. I think the film works and it was a hard film to make work. There are a lot of brutal, raw things going on in that film and for me, it seemed like a perfect storm of it all coming together and having a fun creative input, but I guess it moved people and they thought the editing works.

It’s a hard film to make work because the style is a little bit upfront. The editing is seen. Where she’s jumping into flashbacks and fantasies. I was happy that it was appreciated.

I have a number of films under my belt, but I started shooting and editing news and cutting music videos and cutting ads and cutting commercials and cutting promos for Dateline. I did all these crazy things before I finally got to do what I wanted to do all along.

But a lot of those things influence and inform the ability to go to her flashback and have it be a music video or to degrade the video in a way — like a Dateline promo where you mash up the video and do all sorts of treatments, so that’s a little bit in my wheelhouse. It was a little perfect storm for what I think some of my proclivities were.

I was quite surprised and it was fun for me because I’m never gonna win, so I can go and enjoy myself — and my wife and I had a really fun time.

I was quite surprised and it was fun for me because I’m never gonna win, so I can go and enjoy myself — and my wife and I had a really fun time.

HULLFISH: What are you looking for of your peers’ work to see that they’re worthy?

KLOTZ: That’s a really tough question. If something is really smooth and I feel like I’m being handled elegantly — the film is being handled elegantly. I think a lot of it has to do with if the style of the editing fits the subject matter.

When you pick that style, is the tone even and working to move the story forward in the right ways? And is it appropriate to the subject matter?

You know when a scene is cut really well because you don’t notice it. You feel moved. You’re lost in the moment. And that’s kind of how I judge. When it does come to voting, what films moved me and why? And then I might go back and see them again or delve into thinking more particularly how the editing worked and what I think went into it. It’s hard because you don’t know. You could have a director who’s just dictating what’s to be done and it could be really well edited movie. The ediotr might have brought a little to the table or might have brought everything to the table and it’s every shade in between. And nobody really knows.

HULLFISH: How closely is your final edit to what was scripted and how did things change why did things change?

KLOTZ: Structurally, this film stayed pretty close to how it was originally scripted.

HULLFISH: Is there another film that you worked on that changed structurally? Precious maybe?

KLOTZ: No. Precious was fairly linear in her growth, from who she started out being to how she ended up.

There were a couple non-linear films that nearly broke the bank. They were really hard when you have so many options. I did a film called The Yellow Birds which jumps around in time a lot. It’s an Iraqi war movie.

Same with a film that’s coming out in a couple of weeks called All Rise that was at Sundance. It was originally called Monster that was very fragmented and structurally moved around.

For Motherless Brooklyn I didn’t even put cards up on the wall because we were going pretty straightforward. But for the other, more non-linear films, I had a magnetic board. We were doing push pins and I’m said, “This is tedious.” I found these little magnetic things that could hold an index card and you can move them around.

For Motherless Brooklyn I didn’t even put cards up on the wall because we were going pretty straightforward. But for the other, more non-linear films, I had a magnetic board. We were doing push pins and I’m said, “This is tedious.” I found these little magnetic things that could hold an index card and you can move them around.

I also learned that when you have a new structure, remember to take a photograph of that magnetic board because once you start moving things around, then they may want to go back. You have it in the Avid, but it’s that visual representation I needed to rely on.

With Motherless Brooklyn the structure didn’t change much but we added some things too. At the end of the film he was driving off and we added a scene where he drops off the information to the reporter. That scene was not in the original script. We decided to change that.

HULLFISH: Joe thank you so much for your time today. I really appreciate you’re talking about this film with us.

KLOTZ: Yeah. Thank you. It’s great. I really appreciate the effort you put into this. It’s a fun listen.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now