In this episode, I’m talking with the editors from the Hulu eight-episode mini-series, Little Fires Everywhere, starring Kerry Washington and Reese Witherspoon. The show’s editors were Tyler Cook, Amelia Allwarden, and Phyllis Housen.

Tyler’s previous work includes the TV series GLOW, Roswell, New Mexico, Preacher, and Minority Report.

Amelia has worked on the TV series Impulse, Boomerang, and Pen15. She was also an assistant on Westworld.

Phyllis was an assistant to the legendary Sally Menke on both Kill Bill movies and has edited the feature films To Whom it May Concern, Confidence Game, Cargo, and the award-winning film Clemency – which I interviewed her about at Sundance last year.

This interview is available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: I’d start with a simple question — and maybe start with you Tyler with this — how did you deliver these episodes? Was it a rolling delivery or did you did deliver everything all at once?

COOK: It was kind of like a mixture. We didn’t have a traditional broadcast delivery schedule where we were delivering week to week but it wasn’t how it’s been with Netflix for us where it was: “Here’s all eight episodes. Go.”

But it was all pushed towards the end and in the last five or six weeks, we started delivering it. The first three episodes — because those aired together — and then every week thereafter we delivered the next episode. Our post supervisor Mandi had to deliver the very last episode at 11:57 p.m. and the stay-at-home order went in to effect at 12:01 am. So it literally came down to the wire. They were working very very hard to get the show finished before the quarantine happened.

HULLFISH: Have you guys seen “I Am Not OK With This?”

COOK: Oh yeah.

HULLFISH: It’s a really good series. I did not know anything about it until just before I interviewed the editors. They got to deliver everything at once. We were talking about how that kind of changed things because they were able to say, “Now that we see the final episode, let’s seed stuff backward to get us to the final episode.” Were you guys able to do anything like that with some of the first episodes?

COOK: Yeah we definitely did. For better or for worse. We were able to keep the pilot open I think until November. We didn’t lock the pilot til November and we started production on it in May, so we were able to do a little course-correcting with that

HULLFISH: Phyllis how were you collaborating with each other?

HOUSEN: We would watch the other editors’ episodes or even between us we would ask questions: “How does this play in your episodes so I can sort of feed into it in a way that makes sense?” And we did a lot of ramping up and down of how hot the arguing got. So we needed to know — from a previous episode — where we were getting in terms of the women and what level of animosity we were trying to create.

HULLFISH: Oh that’s really interesting to think about. You all edited 2 or 3 or 4 episodes?

ALLWARDEN: Tyler and I co-edited episode seven.

HULLFISH: So why was one specific episode co-edited?

ALLWARDEN: It was mostly a scheduling thing. We block-shot the series. Tyler was available more toward the front end and I was more available toward the back end just because I was working on episode 5 and he was working on the finale (episode 8) so none of us had all the time to work on it. So that’s why we split it up that way.

HULLFISH: Getting back to the regulation of intensity of performance over multiple episodes — tell me about making that determination of how far hot or “ramped up” you’re letting an actor get? Also, what tools or resources do you have to be able to deal with that? Like an actor who has delivered multiple levels of performance so that you’re able to actually choose?

ALLWARDEN: I think that that was a constant thing that we were all talking about and thinking about with producers and directors as well. Kerry and Reese would give amazing performances that were very angry or upset. But I’d be thinking, “In Episode 5, I don’t want to go to 100 percent because that leaves us with nowhere to go in Episode 7 and I know that I get to 90 percent in Episode 7 and of course Episode 8 you want to be 100 percent.” So we had a lot of varying performances that we could kind of choose the percentage that we wanted to. I just don’t want to give it all away in the beginning.

COOK: The actors were incredible about giving us a very wide range of options. It seemed to be — in any of those big scenes where they were confronting each other — we had the entire range from zero to 100 to work with and then we got to kind of modulate how we felt it would work best.

That was a lot of the back and forth that we were going over when we were doing our various cuts. Even in the pilot we weren’t sure exactly where we should start their relationship. Should they be sort of feeling each other out? Is there already some aggression? Are they kind of playing nice with each other?

That was kind of the biggest riddle to solve with the pilot because we had to leave room for where the rest of the series was going to go. So we would constantly push and pull that dynamic as we started getting more episodes in and more footage — seeing where their performance should live.

HULLFISH: An actress asked me to do a talk from the editor’s perspective — what do editors want actors to know?

HOUSEN: Hold your prop in the same hand. (all laugh) DO it the same way and then say the lines differently.

ALLWARDEN: I always tell actors that in a big dinner scene or conversation scene where they don’t have a lot of lines to give a lot of acting without dialogue — things to cut to. I’m always cutting to actors more when they’re giving more. Or I’ll cut out actors who just turn into a doll when they don’t have lines.

HOUSEN: That’s a good point. And we had a lot of dinner scenes.

HULLFISH: If you’re giving non-verbal responses and you’re not the one talking, you can still get a lot of screen time by acting absolutely 100 percent of the time.

HOUSEN: Absolutely. Yeah.

HULLFISH: Did it make any difference to you or did it cause any complications for the audience to basically know what was going to happen? You know from the beginning that there’s gonna be this fire.

HOUSEN: From people that I watched with — we watched together every week, they were super excited — and they made bets. They kept guessing. There was a lot of “what’s going to happen?” There was a lot of excitement about that. And I think we did a good job of keeping the truth.

Everybody really thought it was going to be Izzy. People who read the book, of course, thought it was gonna be Izzy. Episode eight! Tyler, man, you fucking crushed that! When the fire happened that was just off the charts. Everybody I was with, they were just blown away.

ALLWARDEN: Also at a certain point you care less about who set the fire than you do about some of the things that are happening between characters. The metaphorical fire become more important.

HOUSEN: We had fires in every episode I think.

COOK: They definitely threaded them through. I will share an interesting anecdote from when we were assembling the pilot. We didn’t shoot that scene at the beginning of the episode with the aftermath of the fire where Elena is sitting in the back of the ambulance until the end of the shooting schedule. It was the very very last thing we shot. So for a long time the episode started with Elena waking up six months earlier and starting her day and going from there.

It’s just a completely different episode when you tack on the beginning and we had to go back through and really work the entire episode through a different lens once we got that footage in because without it we were so worried that it wasn’t teeing up enough going forward. It was kind of existing too much in this perfect sphere of “before the fire.”

It kind of affected everything from how we were scoring the episode to our sound design to the performances we were choosing. It colored the lens of the episode to be this happy isolated bubble. But when you put that scene in front, it tinges the whole thing with this sort of bittersweet, “what we’ve lost” mentality to it and it really shaped the direction of the music.

It shaped the point of view of the entire series, because fundamentally everything from that moment in the beginning when the police officer is asking Elena, “Who set the fire?” It’s almost like we’re entering into a flashback of Elena’s point-of-view of the events that led us to that moment.

And that unlocked a lot of things for us musically and tonally to kind of shape the first three or four episodes until we get to the real meat and potatoes of the drama.

HULLFISH: That was something you put at the beginning, but so often we make a change in the middle of a show. And when you do that, you can’t just roll back 5 seconds to see how the cut works. You have to watch how that change affects the entire show from beginning to end.

ALLWARDEN: I think that what Tyler said was a big thing that not only informed the pilot but informed the whole rest of the series. I edited episode 2 and in a lot of ways, episode 2 is a continuation on the worldbuilding that episode one does. But then, after we shot the whole opening and I re-watched the pilot, it layered everything with a little bit of darkness of what’s to come.

So I definitely made some changes in episode two after adding the fire stuff. But I also think — after shooting all the episodes — we didn’t lock any episodes before being done shooting everything, so seeing pieces of the finale informed how we were building the beginning and the middle. And Phyllis did the flashback episode and I’m sure it informed the flashbacks as well.

HOUSEN: The flashback was interesting in that it was really a standalone episode. It was so different from everything else. This was really my first foray into series television, and the producers kept saying, “We have to approach it like a pilot! We have to approach it like a pilot!” I didn’t know what that meant.

But we were introducing basically new characters that no one had met before, so they kept wanting me to add ADR to better explain to the audience who these new people were. Also episode six was shot in a really different way. The director came from music video and she shot it in a very mosaic or montage-y way.

We kept going from one person’s past to the other and trying to parallel where they were coming through in their lives. I sort of went with the story and followed the script. Everybody loved the characters and the actors did a great job picking up the idiosyncrasies of the older actresses.

HULLFISH: For someone who hasn’t seen the show, can you explain what you mean by “younger actresses” and “older actresses?”

COOK: For the flashbacks, younger actresses were cast to play Reese and Kerry’s characters’ younger selves. The “flashback” actresses did an amazing job in picking up Reese and Kerry’s acting idiosyncrasies.

HULLFISH: You catch on pretty quick, but as a viewer, but I remember when the young blonde in the flashback came on, it took a moment to figure out that she was playing the same character that Reese was playing. Was there a trick to trying to introduce that?

HOUSEN: We had the other characters ADR the name Elena in when they were speaking with her, even if they didn’t say it when they shot the scene, just so it would clarify.

I thought we were overdoing it, but they said we really should do it as much as we can fit it in, and so we did, and I think that helped. We stopped doing it after a while, but in the beginning we did it quite a bit.

HULLFISH: The relationship between a director in a feature film and the relationship with a director on a TV show is different. The relationship on a feature film is more like a showrunner in TV.

COOK: I’ve worked with Lynn Shelton quite a bit in TV and in film. It’s interesting to have our relationship kind of change depending on the medium we’re in. We started in TV together on GLOW and I edited five episodes that she directed. Then I cut a feature that she did.

The director has only three days of an edit with a TV show and then they move on to their next thing and then the showrunner is the one in charge. Versus a feature where they are there every single day. They make all the decisions. As an editor in that position — especially for me who has such a strong relationship with Lynn — when the director steps out, you have to assume the role that they had, which is advocating for their original vision.

I think you also are advocating what’s best for the material. It becomes a little decentralized in a sense because you’re fighting for the entity as opposed to this person’s vision or that person’s vision. What’s best for the episode and then what’s best for the larger piece. Everyone has a different relationship.

Lynn obviously directed four of the eight episodes so she had a very strong hand in guiding the show. But when (directors) Nzingha Stewart or Michael Weaver stepped in it definitely was a little bit more of them saying, “This is what I think it should be, but obviously if that interferes with what you guys are setting up, I defer to you.” So you become a little bit of a….

HULLFISH: Steward?

COOK: Yeah, for the material. You’re there to try to take these varying visions and coalesce into a single thing.

HOUSEN: And not lose what the flavor was in the beginning, because there’s a lot. The difference for me — and there are many, many differences — but there’s a lot of cooks in the kitchen in TV. When I first got there I didn’t really know who to listen to. Who’s got the most power? The most say?

You want to go for the best choice and the best decision for the piece, so that doesn’t change. You still advocate for the work. I was shocked really, when I found out that the director has three or four days with the material and that’s it. “What do you mean you’re leaving?” I just wasn’t used to it all.

Another thing that was really interesting and kind of shocking to me — I don’t know if this is on every show, but it was on this show — you cannot cut a word of dialogue until a writer comes in or a showrunner comes in and says you can cut that. I thought that was very interesting because in film we just cut. We cut away whatever works and create what we want.

And then when I worked with Nzingha — while she did an amazing job directing and I thought it was really interesting and very fluid and had a very beautiful feel to it, she went onto another show. So I had zero time with her. I had three hours with her total and we ultimately went back to the editors cut and then we kept watching her cut to see what it was she wanted in those three hours that we got. But ultimately, Liz Tigelaar, the showrunner and I put that together without really a director’s cut in the middle.

HULLFISH: Amelia, what the transition like between working with the director and then switching over to working with the showrunner? I’d never heard Tyler’s comment before that people are actually advocating for the director. I always thought that you were always going with the showrunner or just advocating for the material itself.

ALLWARDEN: Hopefully, the director and the showrunner have the same vision. So when you’re advocating for the director you’re also advocating for the showrunner and also advocating for the footage that you have or the story.

HOUSEN: A girl can dream!

ALLWARDEN: Like Lynn was an executive producer on the show as well so she was very ingrained in all the conversations. So like Tyler said, I tried to advocate for her vision.

I feel like I usually work with people in TV who have a similar vision as the director — or at least are on the same page. So when I’m transitioning from the director’s cut to the producer’s cut, I haven’t felt that big of a jarring difference because I don’t really put it in terms of “this was the director’s idea and this is your idea and this is my idea.”

I don’t want to be right. I want what’s best for the show always. It’s just about whoever has the best idea.

HULLFISH: Some of the other editors that I’ve talked to have been on shows that have been much more established, so in those cases, the editor has been on the show for maybe six years. They know the show way better than any director they could ever come on.

You guys were all a little bit more together at the same place. No director was coming in fresh where you’d been 10 years with the same storyline.

ALLWARDEN: Since this was a mini-series it’s more like making one long movie that begins and ends and isn’t going to be a continuing series.

My experience actually is mostly first season shows so I get a lot of the same experience of finding out the tone and style of the show with the showrunner and the director versus coming in later in the series that’s already established exactly how they do things.

HULLFISH: You were mentioning the fact that all the footage was shot before you finished editing. Were you watching the dailies just per episode or were you getting ahead and seeing stuff for episodes that you weren’t even necessarily cutting at the moment?

ALLWARDEN: We did block-shoot everything, besides the pilot. 2 and 3 were shot together and 4 and 5 were shot together. Then 6, 7, and 8 were all shot at once. So we were all getting footage on different days and out of order.

I didn’t watch anybody else’s dailies, but our rooms were all next to each other we’re all constantly talking about, What did you get today? And “How’s it looking?” And “How is this person acting?”.

HOUSEN: Or if you needed something — you are missing a shot — maybe it came in the dailies for another episode – If you needed a particular shot of the house, for example.

ALLWARDEN: I definitely stole stuff: a look or something that might have been in the same location.

COOK: For 7 and 8 particularly we were getting everything all at once, so if I was cutting a scene that kind of played directly off of one in episode 7, I went into Amelia’s room and asked her to show me her assembly of that just so I would know the world they were living in. That way I can build off of that.

That was sort of like a shortcut since we didn’t have time to sit and watch dailies of each other’s episodes.

HOUSEN: Does that ever happen that you can watch other editor’s dailies?

COOK: Not in TV.

ALLWARDEN: No. I’ve never had time for that.

I think it helped that all of us in editorial really liked each other. We liked to collaborate. We ate lunch together every day.

HULLFISH: The editing team for I Am not Okay with This were actually doing much more collaborative editing. Much more like two feature film editors than a team of TV editors. They were watching each other’s dailies.

HOUSEN: Wow.

COOK: That’s a luxury.

HULLFISH: What was the schedule like per episode or for the entire series?

COOK: I think we started shooting the pilot at the end of May and we locked the last episode in January or February. Which actually — for eight episodes — is longer than I’ve had on other shows. But I think what made this one a little bit more complicated is every block was about 32 or 34 days something like that. So there was just a lot of time waiting for your show to be complete.

HOUSEN: A lot of hurry up and wait. You’d wait for dailies and then you’d get them and then it was due in two days.

ALLWARDEN: We were block-shooting and none of us were ever editing both episodes of the block. So sometimes I would get a half-day of dailies for a whole week. So I’d be really caught up, and then I’d get inundated. The way they shot was very director-based.

HULLFISH: Then was it like a TV series where you’re also trying to not only view your dailies, edit them, but then you’re also doing notes from a previous episode and then doing a mix on the show before that one?

ALLWARDEN: Once we were finished filming it kind of all fell into a normal TV-Land schedule. That’s part of the reason why Tyler and I co-edited episode 7 because he was waiting for dailies on the finale and I was doing notes on episode 5, then all of a sudden he was getting dailies on the finale and I was free.

COOK: And I was still doing revisions on episodes 1 and 3 while I was cutting dailies for episode 8, so I kind of had four episodes up at one time. I would walk into the post producer’s office and just ask, “OK. What am I focusing on today?”.

ALLWARDEN: One interesting thing about this show was that — at least in my experience hasn’t been common for TV — we were editing on the same lot where we were filming the show, so our showrunner and our producers and directors had a lot of freedom to run back and forth between set and editing and so did we.

I occasionally would go to set and talk to a director about something. Because they’re so busy, it’s just easier to walk up and talk to them in person. It allowed for them to say, “OK, now we have 45 minutes to work with somebody because they’re turning around the set and they’d run over and look at it and then run back to set.”

So that was atypical for me in terms of my television experience.

HOUSEN: Yeah. I would wait in my doorway. I was told they were coming to see me, but no, they were going to see Amelia.

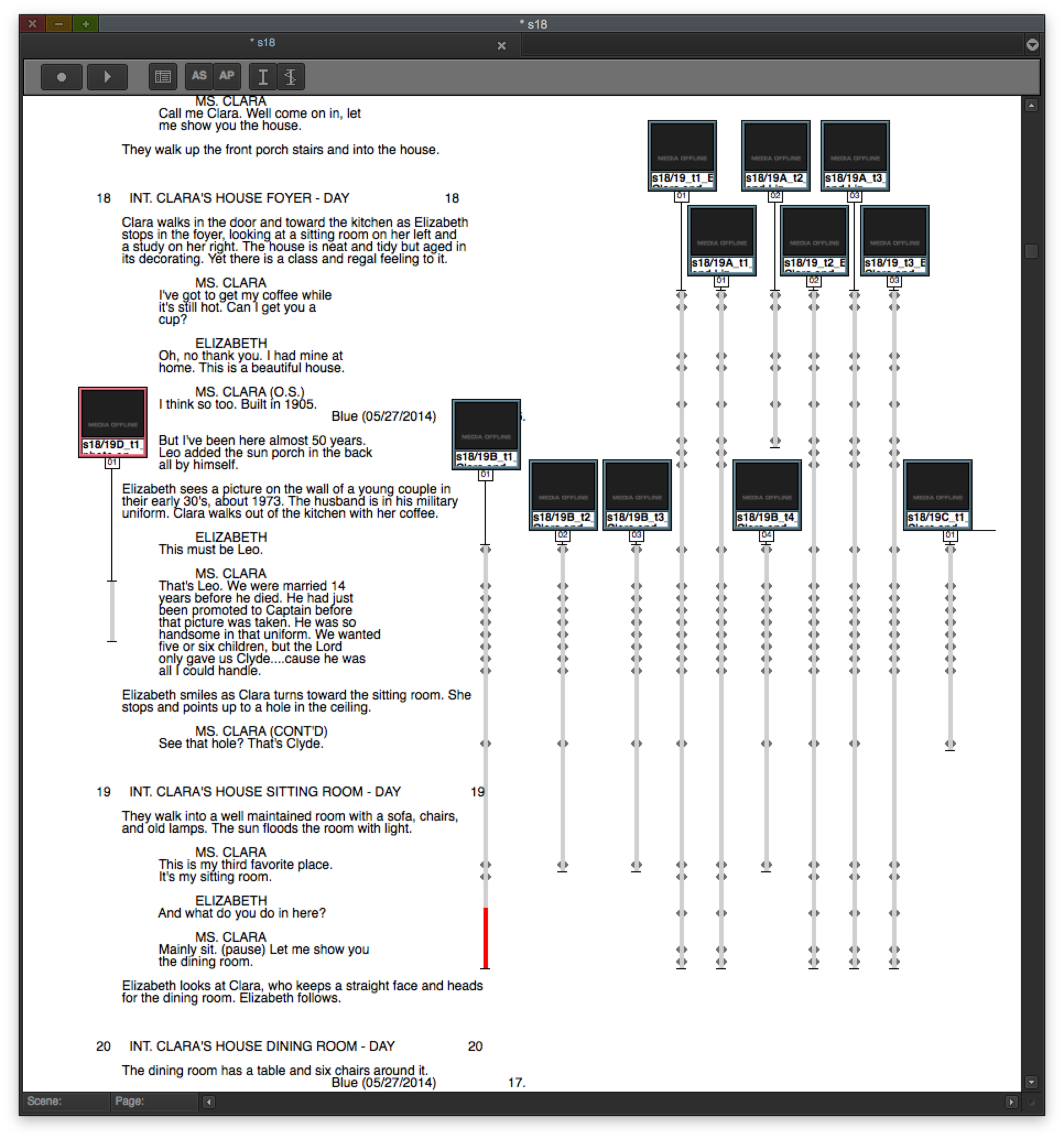

HULLFISH: I’m assuming you’re all cutting in Avid.

ALLWARDEN: Yeah.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about organization, because if there’s a possibility that you might swap or share an episode or somebody else is dealing with notes for you or something like that, are you all organizing your bins the same way? Was there any thought about that?

COOK: We had to have a little bit more of a combined conversation because we knew we were gonna split episode 7, so we wanted to make sure it was friendly for both of us. I use ScriptSync and so does Amelia. I just wanted to make sure I still had access to ScriptSync.

ALLWARDEN: When we were combining episode 7, my assistant editor and Tyler’s assistant editor got together and looked at the ways that Tyler and I both organize and realized that it’s 90 percent the same. We came up with a combined way that we all agreed on and it worked out.

HULLFISH: Then with ScriptSync, it’s always a question of allocating the assistant editing resources since it’s so time-intensive.

HOUSEN: They took my assistant too. Some days they needed a lot of assistant work.

HULLFISH: Did you do the ScriptSync for every single scene? Or do you look at the scenes and say, “This is a scene where I really don’t need ScriptSync?”

ALLWARDEN: If there’s barely any dialogue, then I tell my assistant not to script it. But any big dialogue scenes for me I script. My assistant editor, Brian, scripted HUGE dialogue scenes. Big speeches. Courtroom drama stuff. But anything that’s like 10 lines of conversation between a character, unless he had nothing to do….

HOUSEN: Which is never.

ALLWARDEN: Sometimes he would catch up and then he would just do those small scenes just to have them. So that was great. But I wouldn’t prioritize that.

HULLFISH: And do you cut exclusively from ScriptSync? or are you just using it for various parts of the process? Or for the whole thing? Or just for your rough assembly? Or it’s only for the director notes?

ALLWARDEN: I edit half from the bin and half from ScriptSync, both when I’m assembling and with producers. I think it mostly comes in handy when producers and directors are there and we just need to audition performances of a certain line. So that’s when it’s most useful to me. However, that does make my assembly much quicker using ScriptSync.

COOK: I had tried a half and half approach, but I’ve migrated to editing only using ScriptSync unless it’s just an action scene. Like when they set the house on fire there was nothing to ScriptSync.

It gives you a nice roadmap of the footage. It’s a good visual representation of the director’s shooting plan. It’s like looking at the facing pages of the script notes and it kind of makes it a little bit more digestible. You watch everything the same way you always do but once you start to actually assemble I feel like it helps me. I can mark up in the script from this line to this line of this take is my preferred take and so on and so forth, so it helps you click through the assembly and I’m very much the type of editor who just wants to get an assembly up on its feet as fast as possible.

And then it’s the repetition of going back through over and over and over again and kind of stress-testing the edits and the performances and the choices I made to see if I can flesh it out more. So getting an assembly up and running as quickly as possible is sort of like my go-to way of working.

HULLFISH: Phyllis, did you find that you needed to change your process of how you approach a scene from feature film to scripted TV?

HOUSEN: I definitely did. I found there was not necessarily a way into the scene the way there is in cinema. There were a million ways to get in and in the beginning I sort of got stuck. What I found worked for me: is I would find something in the middle of the scene that works — that I understood — and I’d put that moment together and I would work from the middle out to the beginning and the end. That was a really interesting way to put a scene together — for assembling.

And then of course I would go back and go through the scene and work the scene, but I just sometimes felt paralyzed because there was no “tilt down from the clouds to the ground. Pan to the car. Car stops. Door opens. Foot steps out.” In TV you get the foot.

And I don’t use ScriptSync but I would really like to learn how. I think it would be very, very helpful.

HULLFISH: You guys didn’t help her out with the ScriptSync thing?

HOUSEN: I didn’t ask, really. I thought that was another layer I didn’t need. This was my first TV series. I was new and so I felt like I just need to get into the material and get it done. I didn’t really have time to learn anything particularly new.

HULLFISH: Is that difference in the challenge of TV based on the coverage that you’re getting? That’s what I feel like I’m hearing.

HOUSEN: I think so. Again this was my first show. I don’t have a lot of experience or anything to weigh it against. I think that they try to get as much coverage as they possibly could in a certain amount of time that they had. There was no 10 minutes shot like from The Player, and so I had to find a different way to approach it.

HULLFISH: You guys want to push back on this theory or agree with her?

ALLWARDEN: First of all, I’ll say that when Phyllis told me she works from the middle out of a scene I said, “That’s the craziest thing I’ve ever heard” i’ve never cut a feature so I have the opposite experience as Phyllis.

My instinct is: in TV you just have to pick a way in and go with it. Because there are a lot of options, but I do feel like there were a lot of strong cinematic choices made by our directors, but then there were other ways into the scene as well. So it’s an abundance of riches in that way because there are just so many ways you could do it. You want to get it right, but I think a lot of editing is just instinctual.

COOK: I think Amelia hit on a good point which is that fundamentally TV directors are used to giving options whereas feature directors don’t have to do that. They get to choose: “I’m doing it this way!”

A lot of times it’s a pacing thing. I feel like directors will shoot these big epic cinematic entrances into scenes and then the showrunner comes in and says, “Let’s chop off the first nine seconds of this crane shot and just start where the action starts.” And that just fundamentally becomes a time issue.

On this show I think the pilot was supposed to be 60 minutes and our first cut was 90. We had to really find ways of moving the story along and getting it closer to 60 minutes. I think we all wanted a 90-minute version of that show, but we knew that we couldn’t deliver that and we had to figure out a way to pace the episode in such a way that it still had the same feeling as that 90-minute version, but wasn’t going to put us into that hour-and-half territory which is just I think fundamentally always the TV conundrum — and it’s changing obviously as networks are getting more comfortable with extended episodes.

I always say that the cut right before the lock was always my favorite because it’s the one that felt perfect pace-wise before we had to go in and chop two minutes out.

But back to your original point I feel like TV directors have gotten used to providing those options so that way we’re not hamstrung when we have to get to that moment.

HULLFISH: Phyllis, since you’re not using ScriptSync, are you editing everything from the bin? Do you start making selects reels? What do you do?

HOUSEN: I watch dailies and build as I watch.

HULLFISH: You start building the cut as you watch?

HOUSEN: Yes. I build the assembly as I watch. It’s what I’m used to. If I like something and I keep going and watch another one and if I like that one more, I’ll switch it out. I just go through dailies and work from the bin.

HULLFISH: To get back to the idea of Phyllis cutting from the middle, that’s something I’ve heard from several editors, and when I talked to Walter Much, he described being on a panel with another editor who said he always edited from the end of the scene backwards.

HOUSEN: Thank you.

HULLFISH: You find the moment that you know has to be the core moment and then you go from there. Everybody’s got a different technique which is why I do this series.

HOUSEN: We’re all a little weird.

HULLFISH: Nobody does it the same. Do you use locators?

HOUSEN: I remember or I write. I still write things down.

HULLFISH: On a piece of paper.

HOUSEN: I do. I write everything in a notebook.

ALLWARDEN: I do that too. I write on the facing pages.

My method is: I read this scene again and I watch all the dailies and while as I’m watching — if there’s anything I love — I put it in a selects reel or if it’s just a take I love or a bigger note then I’ll write it on my facing page next to the take. And then I finish watching all the dailies and I read the scene again and then I cut the scene.

HOUSEN: I can’t wait! The first time I like a take, I’m like: I gotta go! I just put it in the timeline.

ALLWARDEN: I need to see it all before I can envision where each setup is going to be within the scene and I kind of cut it in my head and I start by setup and then I go by performance at the end.

HULLFISH: Tyler it sounds like you’re much more ScriptSync based. Are you putting notes or colored markers in ScriptSync?

COOK: I’m not putting it in ScriptSync itself but I will use spanned markers: from this moment to this moment on take one I love this performance or these performances. And I feel like I can live in that take.

So that gives me a blueprint where I can just go back to each take, grab the markers and throw it into a sequence and that becomes a good starting point. But I’m a little bit like Phyllis in a sense, too. If I see something that just grabs me, I will cut it in and know that it will be a big building block in the scene.

There’s always that push-and-pull because I may love a performance in take three but it may not match with the other side. Those balance issues are something you have to consider.

HOUSEN: That’s the job.

COOK: As much as you watch the footage it’s a little bit of what came before, so you’re always changing and modifying and shaping based on what you did.

A lot of times a director or showrunner will say, “Oh my God! That’s the take! Why didn’t you use that one?” And I’ll tell them, “Well, in the original construction, that one could not have possibly lived in the performance but now as we’re shaping it in a different way it has a place and it IS the right take for this moment NOW, but three months ago it would never have worked.”

That’s the missing thing: that contextual relationship of all the pieces. That’s the thing I’m really thinking about when I put a piece together.

HULLFISH: That’s a tricky thing with watching dailies right. When you watch dailies you don’t know where that scene is gonna be cut more months from now.

HOUSEN: That’s right.

HULLFISH: So something you think, “That’s not a great performance.” when you first watch dailies can end up being the performance that the successful cut hinges on.

COOK: 100 percent. And more times than I can count.

HULLFISH: I know it’s a failing of mine but I think of my ego when that happens.

HOUSEN: I think of one of the scenes in Episode 4 with Reese and Kerry in the kitchen — sort of a cat-and-mouse scene — where the cameras are moving around them and they’re going from the kitchen to the front door.

I’d pick takes for Reese that were amazing but then we had to shift them so they were evenly balanced with what worked for Kerry. So it’s always going to depend on the reaction. It’s always going to depend on what came before and what comes after. And that’s the process. That’s the beauty of editing.

HULLFISH: When you watch dailies, are you watching them from beginning to end or from end to beginning?

COOK: I start from the beginning to the end.

HOUSEN: Beginning to end.

ALLWARDEN: Same. And I always watch everything between resets so you can hear the director talking to the actor.

HOUSEN: I do too.

HULLFISH: There’s a lot that editors can learn from what the director tells the actors. Are you learning anything else from that process?

ALLWARDEN: Anything from how the actor’s performance is going to change to how the camera is gonna move differently or how they change the lighting or they ask the actor to sit a little bit more forward because it allows their face to look like THIS. Things that you would just see a new take of and not think, “Oh, they moved a little bit, and therefore I’m thinking this might be a little bit better.”.

COOK: I have the opposite instinct which is: I don’t like to hear what the director says until after I’ve made some choices because I want my own interpretation of what I think is working and where I think the story is going because a lot of times the director does modify those things and then I kind of think it’s the right way even though it may not be.

I want an unbiased view of the material. I will assemble a scene and then I’ll go back and watch that in-between stuff. I’ve found, experientially, that the earlier takes may have something that later take don’t because it just was more natural and instinctual and pure.

HOUSEN: You’re not wrong about that.

COOK: There’s no right way to do it. A lot of times you can convince yourself that you’re right about something and you may not be. Fundamentally when I have the most trouble with a scene or a cut, it’s because I’m trying to force something that doesn’t work. And when I unravel that and just let go of what I was initially trying to do things click into place a lot easier.

HULLFISH: I heard some really interesting advice yesterday which was: reaction shots are better in earlier takes because the actors are a little bit more engaged and so dialogue performances can get better — one through eight — but reaction shots are almost always better early.

COOK: Make sense.

HULLFISH: I want to ask about intercutting of scenes. Did you guys ever modify from the script where one storyline was in or cutting with another?

ALLWARDEN: The first thing that comes to mind for me is the last five or six minutes of episode five. It’s all intercut between Izzy lighting her art on fire, Elena going to Mia’s parents’ house to talk to them about Mia and the image in the newspaper and Bill being at home alone, the aftermath of Lexi’s abortion, Mia developing her photo of Pauline — the big reveal.

So it’s a lot of scenes and a lot of big moments for a lot of characters all having to weave together. It was fairly laid out as this character then this character then this character in the script. There were so many nice moments that join together for me that my instinct as soon as I saw the footage was to intercut it MORE than it was scripted.

It was scripted to be a bit intercut, but I even tried putting all the Mia stuff at the end of the episode instead of ending with Elena’s big cliffhanger line. I tried NOT ending on that and did a lot of rearranging to find what felt most important and most emotional and most leading to the next episode to figure out what happens in flashback.

HULLFISH: What was telling you that this moment leads to this moment?

ALLWARDEN: A visual moment for me was — Bill is in the kitchen and everything’s kind of a mess because Elena hasn’t been home in a couple of days; she’s off in New York. You can see the house kind of falls apart without her and he takes a bowl and he turns on the water in the sink, then I cut to Mia pouring chemicals into the negative developer for her film. So that visually was connecting them.

I felt like keeping the kids apart from each other. We had Lexie putting on mascara in her car after her abortion and then a little bit later we had Tripp in the library with Pearl showing her that he’s renting The Bell Jar. I felt like balancing the adults and the kids’ storyline was also really an important part of that.

COOK: The big one for me is in the pilot — which was scripted to be intercut, but as Amelia said — we really expanded on it in the edit. The moment where they have the orchestra performance and Izzy decides she’s not going to play and then turns to her mother and has “I’m not a puppet” written on her forehead.

In the final cut, that is intercut with Moody and Pearl getting caught in the junkyard.

Also we intercut it with Izzy getting dressed for the performance and changing out of the outfit she wanted to wear then changing into the one Elena wanted her to wear. Some of that wasn’t even scripted originally. We went back and shot new footage after assembling the first cut because we saw this opportunity to really explore Izzy’s motivation and her inner life and what she was experiencing in the moment and how she was feeling completely unseen by Elena.

We wanted this all to reach a crescendo at the same time and we luckily had an orchestra playing that allowed us to match the tempos of everything. When we watched the initial construction — which had everything as separate pieces — it just didn’t really have a rise and fall the way we wanted it to, so we just started playing with it and trying to cram more and more into the orchestra section. Then, it really started to come alive.

But unfortunately the orchestral piece that we had was only forty-five seconds long or 60 seconds long. It could only hold so much so we had to strip away and find each beat’s essence. The big puzzle was to figure out: how do we serve everybody’s point of view adequately in this very small time frame?

It forces you to distill and find footage that can adequately — and in a very concentrated way — tell this story very simply with one or two cuts. Then we just used the rise and fall of the music and its different movements to dictate when we would switch from one character’s story to another character story. That allowed us to speed things up as we got to the end and land that final shot of “I am not a puppet.”

HULLFISH: Phyllis, did you have things like that that you changed?

HOUSEN: That sort of became a go-to in a lot of places. Episode 6 was very mosaic and montage-y. We did combine a lot of scenes there, but there’s one in particular that I’m thinking of in Episode 4 where the theme was always all about mothers and daughters. There’s one particular area in episode 4 that was supposed to be intercut a little bit, but we ended up really intercutting it.

When Pearl had come over to sleepover at Elena’s house and Elena was giving her Lexi’s pajamas and putting her into bed and Izzy’s in the bathroom brushing her teeth and she sees it through the door. Then we cut back to Mia who’s starting to get upset because she’s wrapping up the photograph that she’s sending off to sell. And we keep going back and forth between all of these things and Izzy sort of moves away from Pearl and Elena and we cut more and more to Mia.

Then there’s a scene where Mia’s hand goes on the photograph and you see her ring and at that moment Izzy discovers the ring next to her bedside table that Mia had left for her. So the two of them have their rings at the same time. So we tried to visually connect them. It felt very “rolling” to me.

I think it really brought the four of them as mother/daughter and switching mothers and daughters together in a really interesting way and it was a very emotional scene.

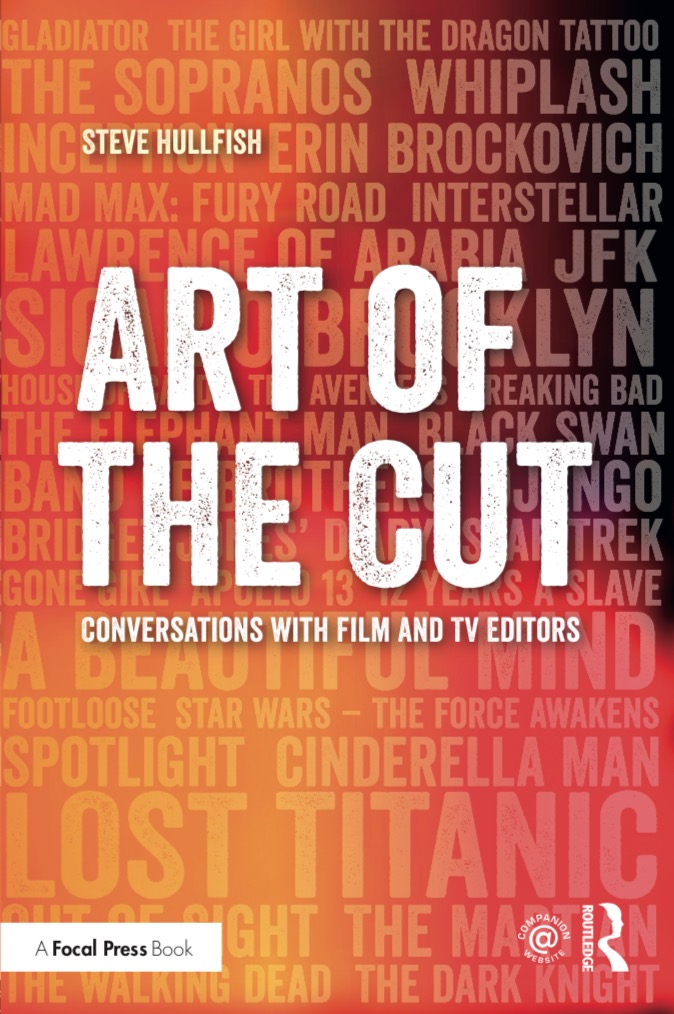

HULLFISH: That’s really a great example. I’m sure we didn’t cover even a tenth of what you guys could talk about with this series, but I really appreciate talking to all of you. Thank you so much for being on Art of the Cut.

HOUSEN: Thank you so much for doing this.

COOK: Thank you.

ALLWARDEN: This was great.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now