Today we’re talking with Tariq Anwar, about working with director Regina King on her film, “One Night in Miami” based on the stage play of the same name. The film is about a fictionalized meeting of civil rights leader Malcolm X, boxing legend Muhammad Ali, NFL Football great Jim Brown, and the King of Soul – singer/songwriter Sam Cooke.

Tariq was born in New Delhi, India, and grew up in London. At the beginning of his career, in the early 1970s, he worked as an editor at the BBC.

His feature film work includes American Beauty, for which he was nominated for an Oscar for editing and an ACE Eddie. He also cut The King’s Speech, which was similarly nominated for an Oscar, a BAFTA, and an Eddie for best editing.

Anwar’s other films include Madness of King George, The Lady in the Van, Revolutionary Road, Law Abiding Citizen, and The Good Shepherd.

If you’re intrigued to learn more after this interview, Tariq published an autobiography that discusses his years in the moviemaking business called “Movers and Shakers, the Monster Makers.”

This interview is available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: Tell me how you got connected with this project.

ANWAR: Very much the conventional way. I didn’t know Regina. I knew her as an actress but not much more than that and she didn’t know me.

I was interviewed, but I imagine there were other editors who interviewed as well. We seemed to hit it off and then she asked me to cut the film, that’s going back to November 2019 I think. Then we had subsequent calls. I was in London at the time, so it was an interview over Zoom.

Once the production started I came over to the States. They shot in New Orleans mostly.

HULLFISH: And did you edit in New Orleans, to begin with?

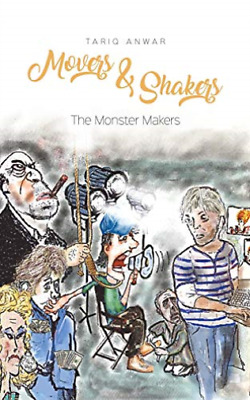

ANWAR: Yes, we were at FotoKem. They have a facility there which was really great. We were there for the duration of the shoot, and at that point, we were quite untroubled by COVID. We just about managed to finish the filming. There were two scenes not shot but they were remounted in L.A, months later.

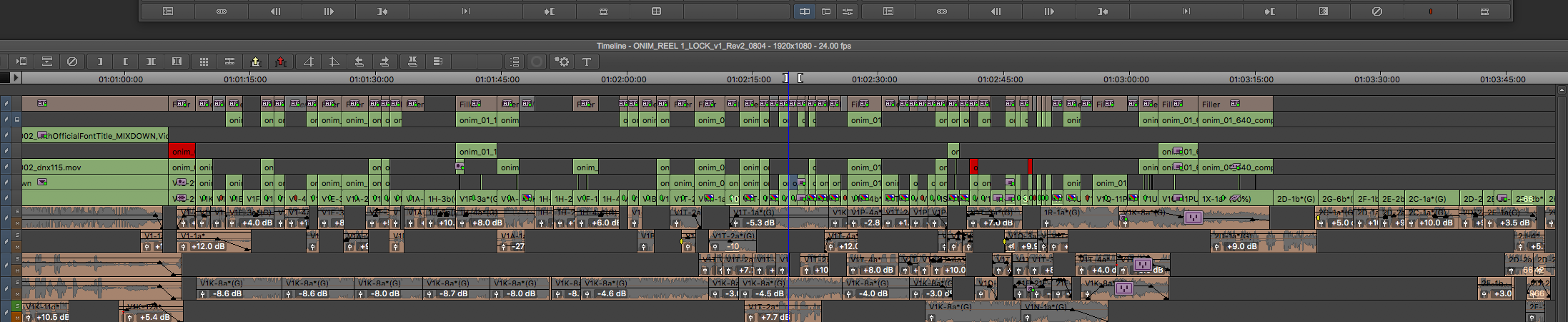

For most of the editing we managed to work together not remotely. It was only in the latter stages after the director’s cut into the producer’s cut that we were all working remotely. At no time were the producers and director in the same room with me in front of the Avid, which was kind of wonderful.

The remote aspect of COVID has really been beneficial.

HULLFISH: It’s been interesting how much it’s changed our industry and the way people are working because of it.

When did you leave New Orleans and move the edit to L.A?

ANWAR: Six to seven weeks we were in New Orleans, so we finished in late February and moved the cutting room to Santa Fe because Regina was acting in a film in there — or was going to anyway — but that was when COVID became a problem and someone on her unit got the virus and so they had to shut it down.

So then Regina was in quarantine for two weeks, and that disrupted the director’s cut. But by that point, she was pretty much happy with the edit. So then I came back to Santa Monica and the production put an Avid rig in my bedroom.

Regina stayed in Santa Fe, not being sure whether her production would start up again, and my assistant Naomi Filoramo stayed in Santa Fe as well so we had a cutting room there and one here in Santa Monica.

By the end of March (2020) about seven weeks into the director’s cut we were posting for the producers and then all the other aspects — like music, sound effects, VFX spotting — were all done on Zoom calls with submissions from the various departments online.

Naomi stayed in Santa Fe and only returned to L.A. when we were well into the sound preparation and VFX.

HULLFISH: Was this movie based on a book?

ANWAR: It was based on a play by Kemp Powers. I’d seen the play in London in 2013. It was an elaboration of one evening they did, in fact, spend together — the four of them.

HULLFISH: So you’d seen the play years before you were asked to be a part of this project.

ANWAR: Yeah. It was fortuitous. You know how difficult it is with interviews with a new director. These things help — to have seen the play beforehand — so Regina knew I was interested in the subject. It just seemed really interesting in terms of dramatic conflict with the boxing and also verbal. The dialogue was just riveting. I really thought it’d be an interesting project. Aside from the political aspects of what the film was saying.

HULLFISH: With some of the movies that have been adapted from the theatre — I’m thinking of some of August Wilson plays — the dialogue is very specific and theatrical, in a way. This felt very real to me. It didn’t feel like it had a theatre background. Did you get any kind of direction on pacing or rhythm or how the lines were delivered?

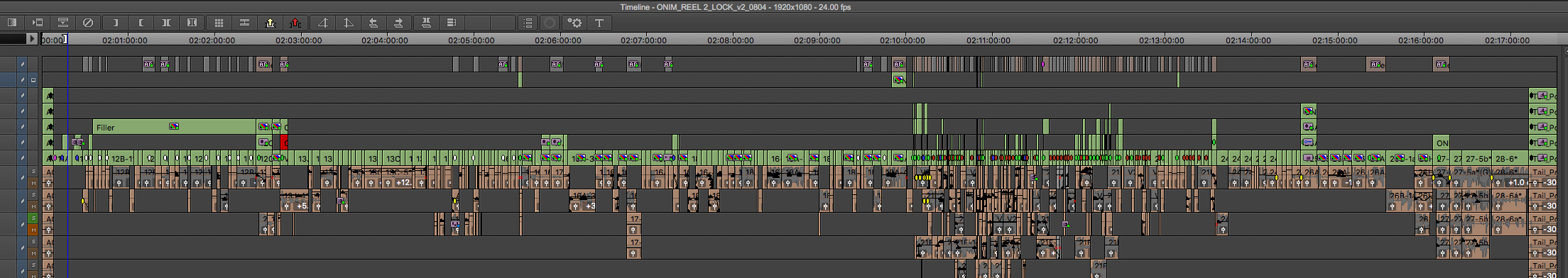

ANWAR: Not really. Regina is the kind of director most editors would love to have in that she wasn’t specific in a micro-managing way at all. Our early conversations were about staging; she said that she would try and make it more filmic, so she was very conscious of that and there must have been conversations in preproduction between Kemp and Regina, the fact that they added new scenes; the opening two fights, the wonderful scene with Brown and Carlton, taking the dialogue out of the room up onto the roof, and the flashback to the Boston ballroom.

All those things were added to make it a bit more cinematic. But in terms of editing, she just let me get on with it which is what most editors like.

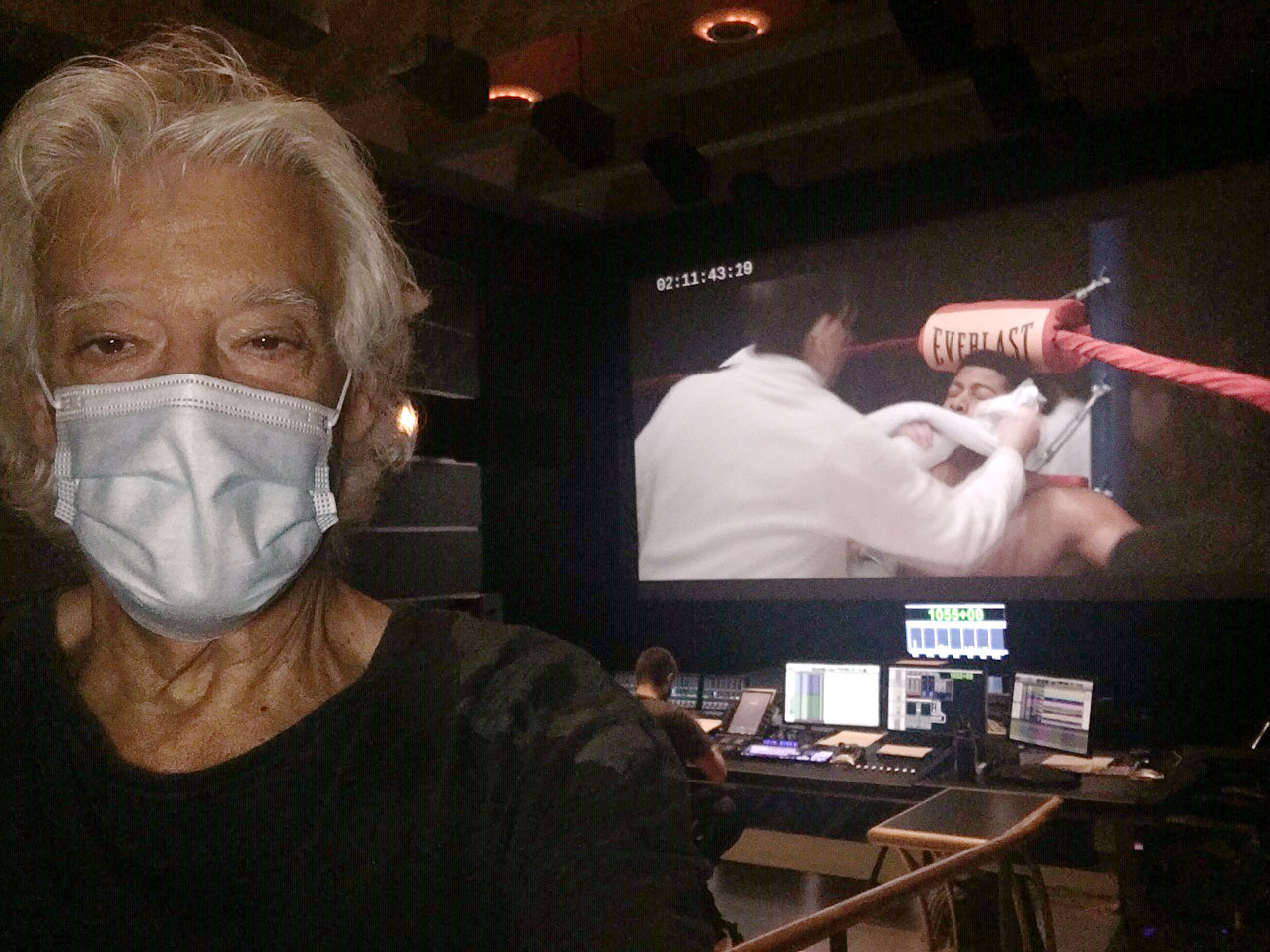

She shot imaginatively. She gave me a lot of material which, as you know, is really helpful. So I was able to vary the shot sizes and to go to different angles. I had plenty of reactions. There was so much coverage — not just in the boxing, but also in the dialogue sequences there were multiple cameras. So there’s was always something interesting to go to and if there was a difficult cut to make from close to wide it was always covered in some way so I didn’t have any kind of continuity issues to deal with which you would have a with single cameras.

So from that aspect, it wasn’t a difficult edit for me. And bear in mind Regina tried to put as much movement as she could into those scenes, either by staging — by getting the actors to move around — or by moving the camera whenever she was able to move within a confined space.

HULLFISH: A lot of it takes place in a hotel room.

We’ve got a scene that we can show people and that we could discuss where Muhammad Ali — Cassius Clay — looks at himself in the mirror and says,. “Why am I so pretty?” That’s a great scene and it has a lot to do with some of the things you just mentioned, which was a wide variety of choices of angles. You barely repeated a setup in that scene from what I could tell.

ANWAR: I think all editors are mindful of not repeating things — trying to avoid it if you can — but you’re so dependent on the material that you’ve been given. So I was able to do all those things, vary the shots.

I was able to do all those things without too much difficulty. But again that was really down to the material as it always is.

The danger with dialogue sequences is to make them too cutty. Constant cutting I personally find irritating. Relentless editing I hate. And so to be able to have those moments where you can intercut between the characters and then put a break in and just hold without having any edits, is good.

HULLFISH: And I also got a sense through the editing of that scene in the hotel room of the geography. As you pointed out she’s keeping things moving with the blocking of the characters moving pretty constantly. The scene could easily have been directed with each person sitting in one spot, but no. There’s quite a bit of choreography in there. Talk to me about trying to maintain the geography so the audience doesn’t get lost in where people are.

ANWAR: It’s a question of feel. You just know when you need to come out wide to show geography. In dramatic terms, it’s sometimes really important to do that. A case in point is that there’s a very long scene after they come down from the roof and there’s a very heated argument between Sam Cooke and Malcolm that leads to Malcolm — referring to Cassius — saying, “His passion comes from a pure place.” To which Clay responds, “Passion is a strong word.”

Aldis Hodge in ONE NIGHT IN MIAMI Photo: Patti Perret/Amazon Studios

Aldis Hodge in ONE NIGHT IN MIAMI Photo: Patti Perret/Amazon Studios

This is such a big moment and was marked by a pause for reactions as directed by Regina on set, but she gave me a lot of material to extend that moment longer than it’s actually played.

The extended pauses really dramatically helped that scene but there’s a wide-shot-reverse looking back at Sam Cooke and Malcolm when Sam walks away. I felt you needed to come to the wide shot as Sam pulls away from Malcolm.

That’s a case where it just feels right and then you post-rationalize: it’s to show geography, it’s isolating Malcolm at this moment by coming out wide and you see him as a small figure at the other end of the room diminished. You do it because it feels right and you only rationalize it when somebody asks like you just did.

HULLFISH: Getting back to that “Pretty” scene, that was another one where there’s a series of wide mediums and I’m interested in why you chose to do that — what the value of that camera size was on his couple of lines?

ANWAR: It’s just a question of feel again. You have tight reactions and then you just need to pull away. It could be a wrong move to make. Then it’s down to the director to say, “This is not what I intended. Can you do it in a different way?” But, fortunately for me, Regina and I pretty much felt the same way about the scene, so there wasn’t a great deal of intruding on the internal cutting.

Occasionally, she would swap out takes because she felt there was a better line reading or better reaction from somebody else, and then we’d investigate and change things around, but with her, there’s always a discussion.

She would say, “I think this is better. Do you think it’s better? If not, then tell me why.” She wasn’t at all defensive if I disagreed with her. It was a really great environment to work in.

HULLFISH: And sometimes those wider shots are to set up a closer shot on somebody else or a closer moment on that same person at a more important time. You can’t be close all the time, right? You’ve got to choose those moments. It’s a powerful tool.

ANWAR: When you look at the dailies, you kind of sense what the director is looking for. For instance in the Carlton scene — one of my favorite scenes in the film — at the beginning when Brown goes to see Carlton there’s a moment when Carlton says to Brown, “Jimmy, you can always reach out to me” and there’s a huge relaxation on the part of Brown when he hears that. It gives you a sense that he’s not on guard anymore. He’s put his guard down when he (Carlton) says that line.

There’s plenty of coverage, but there’s only one shot that actually registered his letting his guard down. It’s an over-the-shoulder wide shot of the two of them on Brown where he sits back in his chair and crosses his legs, which is a small gesture but you realize, “He’s OK now. He’s with this white guy, but he’s gonna be his friend and everything’s going to be fine.”

When I looked at all the material I knew that Regina wanted me to be on that shot for that moment. I just sensed that she shot it for that precise moment. There are other little clues when you look at the dailies and you can sense what the director is looking for and you put it into the assembly.

HULLFISH: So many people speak about the idea of letting the film speak to you. You see that shot from that angle and there’s something about it that lets you know how it needs to be cut.

ANWAR: Yes. You just know that you have to be on that shot at the moment. And so that affects the shots around it. You know you have to be closer in prior to that and then come out for that movement of leg crossing and then you can go back closer after that. But that moment is so important because it sets up what happens later on.

You don’t think about it consciously, you just look for clues and prioritize text. For instance, in the Carlton scene, the shot through the window looking out into the garden from the interior. It’s a lovely shot, but you don’t want to be on that shot for important bits of dialogue, so you have to choose your moments, use it where what they’re saying isn’t that important.

HULLFISH: That idea reminds me of something I’ve talked to a couple of people about which is: for an important line of dialogue, it should be spoken on-camera.

ANWAR: I think that most editors can visualize a scene as they read it. You can see the performance. You can see the staging in your head and then it’s kind of confirmed when you look at the dailies. Your head’s always working out how you’re going to put the scene together. So instinctively you know the lines which need to be on the speaker and which lines need reactions. It’s just a natural sense that you get. That’s something innate in editors. It’s just common sense in a way because I think you’re influenced by everything that you see. You know how things should be staged and how you’d shape a scene.

HULLFISH: When you approach those scenes do you just read the scene you’re about to cut? Do you read forward and back a little bit? Do you not read the scene at all when you’re about to cut?

ANWAR: I rarely refer back to the script unless there’s a line which I don’t understand — that is mumbled or garbled and I have trouble understanding it, then I refer to the script to see what was actually said.

I am always conscious of possibly missing a moment unknowingly, that has happened to me in the past when I’ve cut a scene and then presented it to the director and they have said, “Oh no. You missed a beat.” And then I feel like an idiot. And if I’d read the script again I would have seen that it was probably marked for the moment. So I do sometimes go back and reread the script.

HULLFISH: What about your approach beyond the script? Are you a selects reel person? Or do you just watch the dailies by calling them up individually from the bin in the order that they’re shot?

ANWAR: I’m not very good about making notes. I just can’t stand the drudgery of making notes or the drudgery of assembly, so the sooner I can get a scene put together, the more comfortable I feel. Particularly nowadays — more so than back when we shot on film — there is just such a wealth of material because the digital age allows directors to shoot so much. And it falls on the editors to actually go through this material and make selections and choices.

Sometimes when you’re faced with a bin or several bins on a scene it’s just kind of mind-blowing sometimes and can lead to sort of a paralysis of editing which I understand.

My process is a much simpler one.

I don’t like wasting time trawling through a multitude of takes prior to assembly. I prefer to stage the scene first in terms of shot selection and then when I feel that the shape is right I review all the other takes and swap them out in the assembly as necessary. And of course, the assembly changes slightly in this process but for me, it’s a far more efficient way to edit and reduce this possible paralysis on facing huge bins.

For me that works the best because you can spend ages looking for the best performance on a line reading. But then when you actually edit it, you’re not on that person anyway, so I think it’s kind of a waste of time.

You shape the scene and know where you’re going to be and then go back and in and drop in the best parts from the other takes as needed.

Starting the scene on the right shot is so important and has a knock-on effect on all the shots that follow. That shot choice is also influenced by how you ended the previous scene. So once you have a series of scenes edited then you might start changing things because you decide to finish a scene on a different shot and that has ramifications on the shot of the incoming scene.

HULLFISH: So it’s finding the right set-up and take to get into the scene and then staying with that until you feel you need another angle or shot size?

ANWAR: I look at the director’s selected takes and pick ones that I think are, by and large, the best ones. I stick with that on each shot size and then just build the scene around them. And then go back and review the other takes to see if there’s a better performance.

HULLFISH: But obviously, as you said, the previous scene can influence the scene you’re cutting and when you’re shooting out of order then you don’t have that previous scene sometimes.

Let’s move on to the director’s cut and how the movie changes as you get away from that editor’s cut.

ANWAR: This film was slightly different. There’s a timing issue with a lot of the films. They’re half an hour, 45 minutes too long. Time wasn’t an issue. I can’t remember what the original assembly was. Probably 10 minutes longer.

HULLFISH: Almost everybody I talk to is easily 20 percent over. 30 minutes over.

ANWAR: Yes, but there wasn’t that problem. And with a lot of films, you find yourself transposing scenes because of narrative. There was far less of that in this film. We did shorten some scenes, mainly because they were just playing too long. The Copa club at the beginning — where we’re introducing each of the characters — was too long. We really wanted to move on to the Brown sequence. So there were some scenes which were reduced down but not to a huge extent.

The biggest problem area was actually when Malcolm X goes to the car park, gets the camera, makes a phone call to Betty and then while he’s out there spots the FBI watching him and then Cooke comes out to find him. Well, that whole section with what Malcolm was doing in the car park and what the guys were doing back in the hotel room was just way too long and in timeline terms, didn’t really play very well.

When you read it, it seems fine but once I was faced with the film as edited there was something really unbalanced about that whole section. He was away in the car park far too long because there was so much going on back in the hotel room.

There was another scene which isn’t in the film — which was within this section — where Sam Cooke comes out of the hotel and just stands smoking and the bodyguard has a conversation with him saying how much he’s been an admirer of his. “How do you write songs? What’s the inspiration for your writing?”

So all that needed to be compressed in some way which involved losing the scene with the bodyguard and Cooke, but also cutting down the banter between the boys and the section with Clay and Brown at the mirror, that had to be reduced down just to give it a better balance and that a better comprehension of the timeline between what was happening on both sides.

So that was really it in terms of scenes. That was the biggest problem area that I can recall.

HULLFISH: As you mentioned, it wasn’t really for time. Many people I’m sure they had that experience or like we just have to get the length down but what you’re talking about is not getting the length down but just a feeling that a segment is playing too long.

ANWAR: Yeah. Maybe it’s because of it being a play. I’ve done other plays. Madness of King George was from a play, and I doubt if we played around too much with that either.

HULLFISH: Do you feel like there was a change in your editing style from when you cut film to when you started going on non-linear editing systems?

ANWAR: I don’t think so. There is a change in editing style, but I don’t think it’s because of going to digital. It’s just because editing styles have changed so much. They’re just so much more cutty now. There’s just so much more internal editing of scenes, whereas if you look back in the past you just stayed on people much longer within scenes. You stayed on a wide shot much longer. You stayed on singles much longer.

ANWAR: I don’t think so. There is a change in editing style, but I don’t think it’s because of going to digital. It’s just because editing styles have changed so much. They’re just so much more cutty now. There’s just so much more internal editing of scenes, whereas if you look back in the past you just stayed on people much longer within scenes. You stayed on a wide shot much longer. You stayed on singles much longer.

Now there’s just this almost constant editing. And of course, I’m influenced by that. I probably cut more now than I did many years ago when I was cutting a dialogue scene because I’m just conscious of this need for pace to keep the energy up the whole time. I don’t know whether audiences are more impatient now because they’ve been subjected to so much more picture cutting.

If you look at any of the National Geographic programs they’re just cutting, cutting, cutting, the whole time. There’s this relentless need to cut, cut, cut which I just hate. You cut fast when it’s appropriate. Not all the time.

HULLFISH: It’s the relentlessness of it. It’s not that the pace shouldn’t go up and down. It’s that it’s constant.

ANWAR: Constant. And in a way, arbitrary. It seems to be just cutting just for the sake of cutting without really much thought and rhythm. There’s no change in rhythm which I think is so important as we discussed earlier.

It’s great to have a hostile exchange between two people, then at some point, you’ve got to let the air out for dramatic effect and then pick it up again. But you need to change the energy levels.

HULLFISH: Dynamics.

ANWAR: Yeah.

HULLFISH: I agree that it is not necessarily attributable to cutting on an NLE specifically. It’s just that styles change.

Do you think it’s because of the amount of footage? You were mentioning how many angles you had here — which gives you more opportunity to cut.

ANWAR: Yeah. Far more is being put on editors in the digital age. I mean not just a question of the huge amount of material we have to sift through. It’s the other things like the VFX now. We are expected to do so much of the VFX ourselves.

In many ways, I’m very dependent on my assistant because I do enjoy it, but I’m not particularly good at it so I do rely on my assistants helping out and manipulating the image and grading the image. Putting movement. There is a case in “Miami” when Malcolm X is on the phone to his wife Betty.

There’s a lovely camera move Regina had tracking round during the phone call. Then we’re on Betty. Then we come back to Malcolm and there wasn’t enough movement in some of the shots. They were very static, so we added similar movement — manipulated the image — so it kind of flowed from Malcolm to Betty.

There’s this constant shifting movement. It’s too limiting in Avid. You can really only track left and right. I couldn’t do that kind of parallax movement which could on set when the camera tracks but also moves around, so that was done in VFX. But now you’re expected to be able to come up with those things. There are many more demands on editors than there used to be.

It’s good in a way because if you like to have control — which I do, which I’m sure most editors will do — you do have that facility to actually control things much more. But I don’t think people are aware that our roles have become more difficult and more challenging and how much more is asked of us.

And it’s on to sound. I think that’s a personal thing — sound. I just love working with sound effects and music while I’m assembling. That’s so important to me.

I never believed in the picture editor doing the picture cutting then handing it over to someone else to design the sound. I think that’s kind of nonsense.

Everything has to happen with the picture editor in your room with the director — or without the director. But you’re creating it all. You’re doing your own bit of writing with the sound and with the music to a certain extent — with the temp music. I think is so important for me — music and sound and picture all come together. They’re not separate entities.

Temp music helps with the picture cutting — kind of informs the picture cutting. If you pick the right piece of music and it really works, it helps guide you through the picture edit.

That was the case with this film as well. I just loved the idea of just having a solo piano track. One of the discussions we had when Regina interviewed me was along the lines of, “How do you like to work?” And I did say, “I like to work with temp music, so would you be terribly thrown if — when I submitted scenes to you — I had music on there?”

She was very reluctant: “Oh really? Do you really have to?” She said to me, “When I watch films, I find music can be really intrusive and it’s too manipulative. I’m really not sure I want to go there early on in the edit.”

I did persuade her. I said, “Let me just try a few things, and if you hate it, I’ll stop.” She let me. And the first sequence I cut was the prayer sequence and I thought, “This is obviously gonna have music on it.” I did toy with the idea of putting Gospel piano which I thought might be going too far for her: being Islamic faith and having Gospel music. It might throw her too much, so to be safe I just put some Armenian flute.

Thankfully, it really appealed to her, so that gave me the confidence to keep on doing it. And I think she felt a bit more comfortable than maybe she should be more open to the idea of having music.

Then I used the Gospel piano piece I was gonna put in the prayer and used it for the introduction of Malcolm X from Brown. So Brown is standing there — after he’s been insulted — and we just hold on that shot and I felt it would make a wonderful transition to have Gospel piano just coming in at the end of that and then coming into the scene with Malcolm X on television making his speech. Great introduction.

So I tried that and again she was okay and then with Clay bouncing on the bed, I picked another piece of blues piano that had a bit more liveliness to it — more energetic, more mischievous, and playful. And so I tried to vary the different pieces of blues piano all the way through. And she was OK. When I put the music there, of course, I changed the picture cuts to fit in with the playful music and it just helped. Whereas if I hadn’t had music, I would have cut it in a different way and then left it to the composer to put whatever he wanted. But I think it was much better to do it the way that I do it.

HULLFISH: So it sounds like you didn’t temp with a lot of previous movie scores.

ANWAR: No. I just downloaded some slow blues piano from YouTube. 10-15 pieces. I just auditioned all of those. The only time where I actually tried to use score was when Malcolm X sees the FBI guys. I just tried to put something a little bit more sinister, more threatening just kind of a sustained thing.

Then the composer, Terence Blanchard, brought in the Armenian flute again with his score. He did something similar but then brought in the flute within that section which I thought was really effective. Then I think he tried it again later on in the film as well when they’re on the roof.

HULLFISH: That rooftop shot is probably similar to the garden one that you were talking about where you wanted to see the fireworks but that’s from behind them, so you have to choose your moment of when to be on faces and when to give that sense of what they’re looking at.

ANWAR: Yeah. But I wasn’t really mindful of doing that. I wasn’t consciously thinking, “I have to come around to the other side just to see the fireworks in the distance.” I was just cutting for the dramatic moments within the scene without being too conscious of where I’d end up in terms of background.

And remember, the fireworks were added, of course, later on, the VFX. There was nothing there at all. The VFX guys did a really fantastic job to bring that to life.

HULLFISH: Speaking of the VFX I need to go back to the parallax thing you were talking about before. Are you saying that you maybe put a little bit of a pan on it but then in VFX they actually made it look like parallax?

ANWAR: Yes. It actually felt as though it was a production shot and the camera was tracking and tracking around the character and it just made it seamless.

HULLFISH: When you talked to Regina before the film, did she tell you how she likes to work?

ANWAR: No. I don’t think she did. There was just a very easy transition to working together. It just seemed kind of effortless. If you read that chapter in the book I wrote there was a section about F. Gary Gray. That was quite the opposite. I mean he was just horrendous.

I was hired. I probably was forced on him. He probably didn’t want me. And when I joined the production we hadn’t had a talk at all. I was hired by the producers and so the first time I met him was when he came to the cutting room after the shoot and the first thing he said to me — he declared, he made a declaration — “this is the way I want to work. What I want you to do is put the scenes together and then I want to look at these scenes again but not just with you and me but with anybody who happens to be around, like my assistants or anyone who’s walking outside. We’ll just draw them as an audience.”

He said, “We’re going to comment on your edit and we’re going to give you notes.” He said, “That’s the way I like to work. I also like to come in late and I expect you to work till midnight. That’s my process.” What do you do with someone like that?

HULLFISH: You said Regina’s notes were not specific more like what I would think a director would give to an actor maybe allowing you some parameters. Tell me how she talked to you about what you were doing.

Photo: Courtesy of Amazon Studios

Courtesy of Amazon Studios

ANWAR: Following the prayer sequence there’s an exchange between Malcolm X and Clay. They stand before he exits the room because Malcolm X questions him about his bad behavior and why does Clay want to upset people?

Interestingly that was one of the early sequences I cut. There are basically only three shots. There are singles on both of them and then there was a wide profile 2-shot of them. That was one of the occasions where she felt I’d cut it too much. She thought I was going between the single’s too much and just felt a little bit too cutty for her.

She wanted to come back to the wide shot in profile and just let much of the scene play out like that. I didn’t really agree with her. I thought it worked fine. But those were the kind of discussions we would have whether she thought the scene was there’s too much at it. There were very few scenes she actually questioned the decisions that I made.

She wasn’t that interested in the boxing. She showed less interest in the two fights than she did in the dialogue sequences. She kind of relinquished control of the boxing to Lionel Stover, who was the boxing consultant.

I haven’t cut fights before. And this was a fight that’s on record. From my point of view, there’s always a temptation to make a completely different fight because the material was so good. I thought I’d throw in about half a dozen more punches and reactions from the crowd just to make it more exciting but of course, I didn’t get away with that.

Regina said, I think you strayed away from the original fight and Stovall confirmed it, so I was reined back on the boxing quite a bit.

Regina said, I think you strayed away from the original fight and Stovall confirmed it, so I was reined back on the boxing quite a bit.

She was concerned sometimes that scenes were playing too long and she would question whether there were possible dialogue cuts to be made within scenes. Those kinds of things we talked about.

We talked to talk about music although she was, by and large, OK with what I put in. She did want to experiment — not so much with the idea of having piano — but having a different style of piano. She was very keen on Aretha Franklin. And so she wanted that style piano.

Bear in mind that it was a really difficult process for her because at no time was she with Terence at any time. She was never in a recording studio with him. Never able to sit with him while he auditioned sketches that he’d done. It was all done remotely and it really is quite a difficult process for her. She did it really well and with such good grace the whole time.

HULLFISH: You talked about multi-cam. Do you deal with multi-cam in a specific way? Or does your assistant set it up in a certain way? Do you use it as multi-cam and switch between camera angles?

ANWAR: I do. I’m very dependent on my assistant for things like that. She sets it all up for me. I kind of treat multi-cameras as separate shots although I have them up on screen as three or four shots on the monitor. But I do sort of treat them as separate shots, so I go to the size of shot and the angle and then insert it as a single shot. But multi-cameras are wonderful because once I have assembled the sequences it’s great to just be able to go to another angle on that. But I do tend to treat them as separate shots.

HULLFISH: Do you remember what your first non-linear show was switching from film to non-linear?

ANWAR: It was a TV show in the UK and that was on Lightworks because Lightworks was the first out in the UK. I was on Lightworks for a long time — about 10 years or so — and only forced into using Avid on American Beauty because the outgoing editor had started on Avid. That was a very difficult change for me.

Then I kind of went between Avid and Lightworks up until the last six years when it became really difficult to get Lightworks. I mean it’s impossible to get one here. Thelma’s got them all, I think.

HULLFISH: What was the TV show?

ANWAR: Harnessing Peacocks (1993.)

Did you work on film?

HULLFISH: I did not. I started on one-inch videotape.

ANWAR: It was a good discipline. You know how unforgiving film edits are. The actual physical edit is difficult and shows up if you run it on a projector, but certainly on a flat plate it really kind of bumps. So it was embarrassing in those days when you made many miscuts because the director was aware of your several attempts to put the scene together.

It did kind of make you think, “I must get the first edit right.” I cut on reversal stock back in the early BBC days — cutting items for news transmission. So the film would come in on reversal stock and you had to be so careful because you knew what you were cutting was going to be transmitted. That was it. So your decisions had to be right and you had to keep the film clean and keep the dirt off it. It was good because you tried to make the decision right the first time.

HULLFISH: Cutting one inch was similar in that it was such a pain to put up the big reel of tape and you wouldn’t want to have to go back in the machine room, take that down, put up the right reel. In ways they’re similar, but I’m certainly grateful for non-linear editing.

ANWAR: Yeah me too. Yeah totally.

HULLFISH: Tariq, it was wonderful to talk to you. Thank you so much for chatting with us about the film.

HULLFISH: Tariq, it was wonderful to talk to you. Thank you so much for chatting with us about the film.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed, and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now