Today, I have the pleasure of interviewing Harry Yoon, ACE again. We last spoke about his editing of The Best of Enemies. We also spoke about the movie, Detroit, which he co-edited with William Goldenberg, ACE. Harry was an additional editor on First Man, with editor Tom Cross and as an additional editor on The Last Black Man in San Francisco. He was also an assistant editor with Stephen Mirrione, ACE on The Revenant – all movies featured on Art of the Cut in the past.

This time, we are discussing the film Minari, which he edited, and that has drawn critical acclaim and buzz as a contender for Best Picture at this year’s Oscars. It also won the Grand Jury award and audience award at Sundance this year. And received multiple awards at the recent Boston Critic’s Awards, which is often indicative of Oscar success.

This interview is available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: It’s so good to talk to you again. I love Minari. I can see why there’s an Oscar buzz about this. Tell me a little bit about getting connected with this director. How did that happen?

YOON: The introduction came through Christina Oh, who is a producer at Plan B. I met Christina because we worked together on Last Black Man in San Francisco. From the first time we had a conversation, we really hit it off just because we were both Korean-Americans and 1.5 generation that had grown up and worked our way up in the industry. We both had a passion for telling Asian-American stories but also knew that we had to find the right one. One that satisfied the artistic and commercial ambitions that we both had.

So for Last Black Man — which was a really positive experience and we all became like family during that project — I was an additional editor. I joined David Marks who was on through the beginning of post-production and then I came on and helped them get to the finish line. She called me while I was on Euphoria and she said, “I read a lot of Asian-American scripts about the immigrant experience but this one is really special. It’s about a Korean-American family and I can’t think of anybody else that I think would be better to edit it.”

When you get a call like that….

HULLFISH: Your ears perk up.

YOON: Exactly. And it was through her that I was introduced to Isaac. We had a number of conversations. He was actually finishing up a teaching job in Seoul, Korea at the time. He’s from the States but he was a visiting professor there.

Even with the time difference, we had some really great conversations about the script and about how meaningful it would be for both of us because we are contemporaries. Our families moved over in the late 70s early 80s. We both grew up as kids who were part of that Korean diaspora over here and with immigrant families that worked really hard to get to that next rung on the ladder of the American dream.

We had a lot that we shared and a lot to talk about. And that’s how we met and got to work together. It was like a dream. I think for every editor — particularly ones that work in features — you dream about meeting the Scorsese to your Thelma.

HULLFISH: (laughs).

YOON: You dream about those people that you just have that creative and personality compatibility with. I feel really blessed that I was able to meet Isaac and hopefully we’ll be able to collaborate together on his future films.

HULLFISH: I watched a little bit of a Q and A session with the director from the Hawaii Film Festival, so I know that they shot in Oklahoma just outside of Arkansas, right?

YOON: Correct. It was right outside of Tulsa. So for Isaac, it was very important to get the landscape right because the land is such a character in the film and it has a kind of almost mythic meaning — especially for the lead character, played by Steven Yeun. He wanted the feel of that to be correct and so they definitely wanted to shoot in an area that — landscape-wise — was similar to what he grew up in when he was in Arkansas.

HULLFISH: And the other considerations were probably more logistical I would think.

YOON: I think practical too. I think they were thinking about shooting in Georgia for a while and Plan B and A24 moved a lot of their stuff to Oklahoma because they had similar tax credits and because a lot of productions were doing that, Oklahoma City was kind of saturated and so they found a little more room in the Tulsa area. Also, the landscape of the Tulsa area was more akin to what he was looking for.

HULLFISH: Then where were you?

YOON: I was in Los Angeles. A24 has a general space that they rent as cutting rooms that is a converted warehouse that used to be an exterminator’s office and the outside it says Exterminators so it’s super-non-descript. They kept all the pictures of the beetles and the bugs and stuff like that, so as you walk in you’ve got like Murderer’s Row of the bugs that they used to hunt down and that’s how you’re welcomed into the facility. It was great.

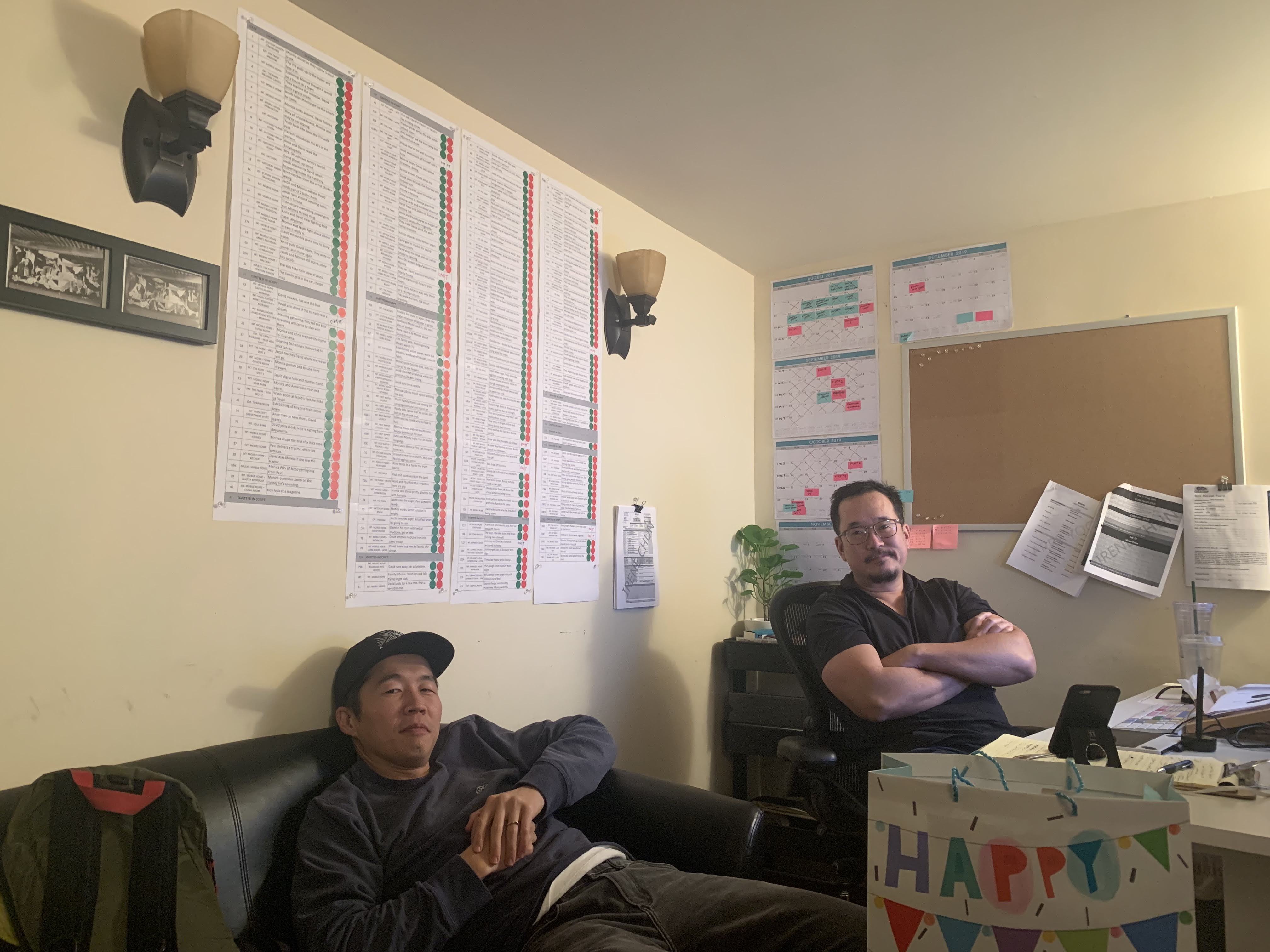

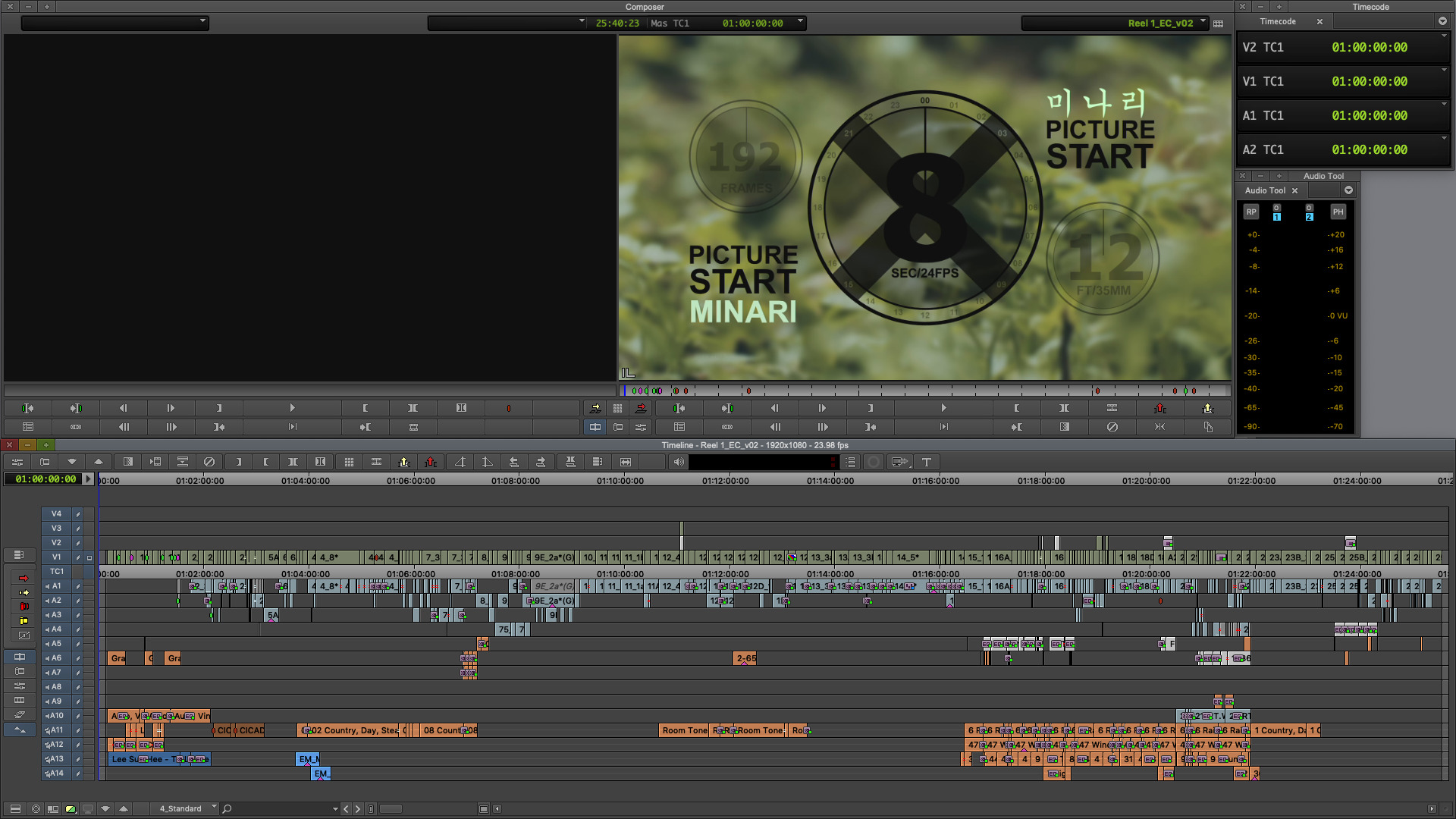

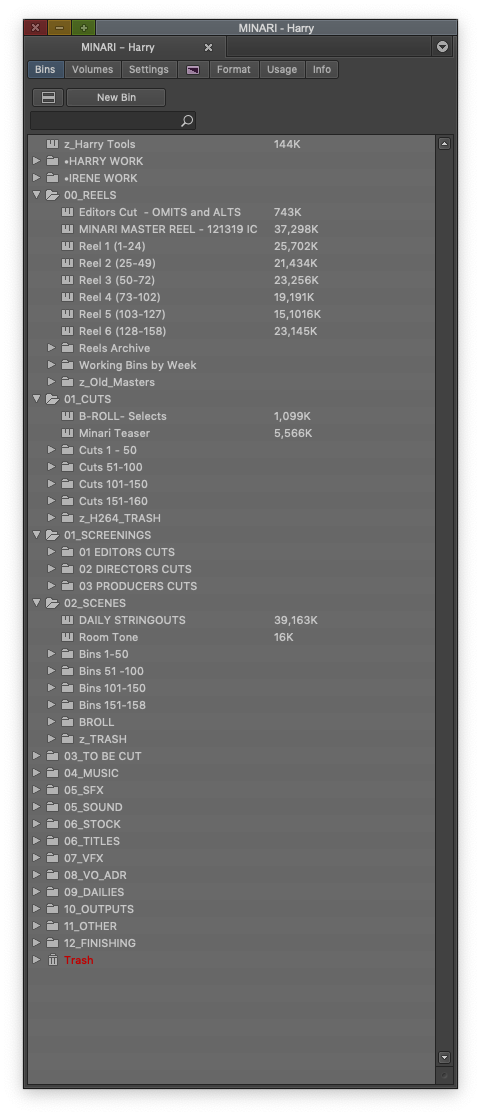

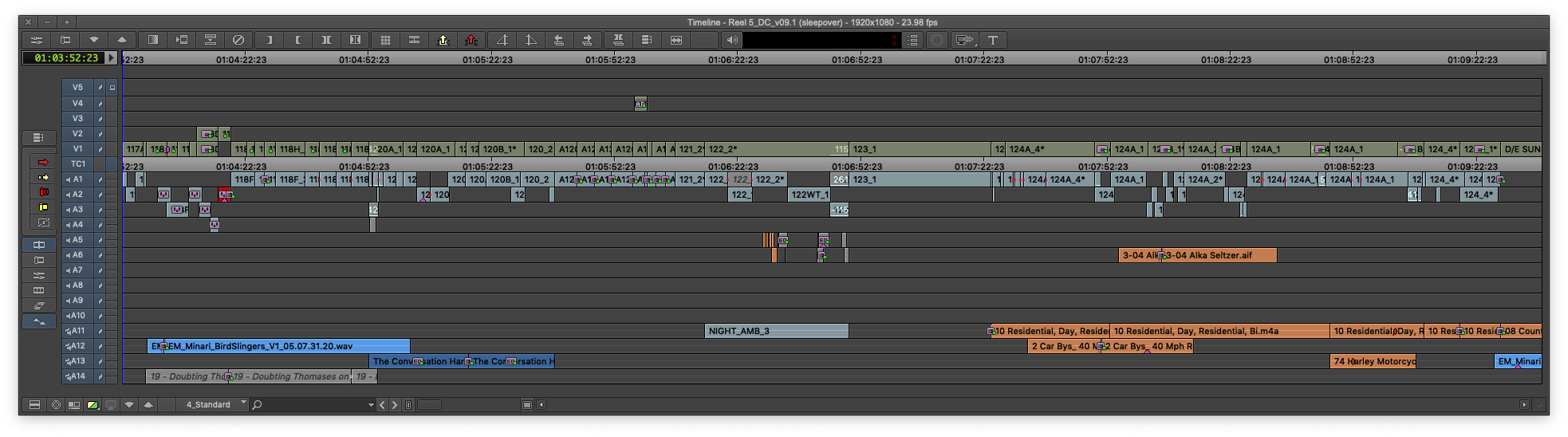

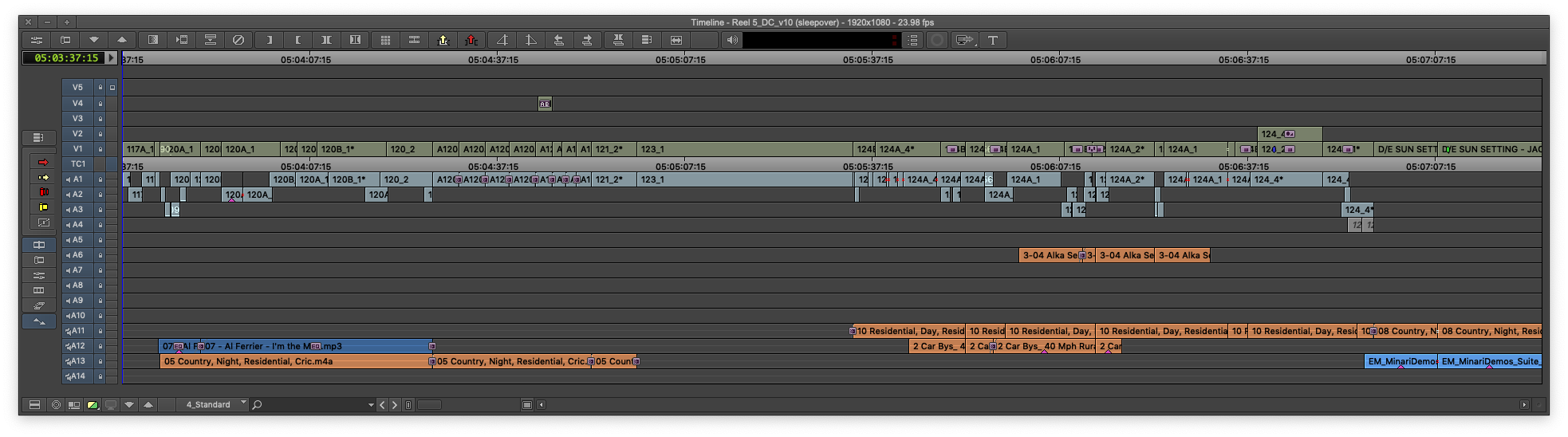

It was very intimate because it was just me and my assistant editor Irene Chun in that smaller warehouse space for a long time, so it felt like having the luxury of your own extended cutting room. It was nice.

HULLFISH: You were getting dailies through the internet or PIX or….

YOON: We had a really incredible jack-of-all-trades DIT on set named Jon Roman who was also the 1st AC. We’re just so lucky with some of the people that we got. He was also Korean-American, as well. He not only did a lot of the conversion, but he also used his own internet out of an apartment that he was renting to upload the dailies so that our assistant editor, Irene Chun, could download them.

He would upload them at night and in the morning we would download them. We used a particular flavor of Aspera to get that done through our Avid vendor.

HULLFISH: How much interaction did you have with the director during dailies? Or was he just head-down getting stuff done production-wise?

YOON: Quite a bit actually. I think this is often the case with low budget indie productions. I think you do have the opportunity to play a big part because the production is always resource-constrained. They always have a plan but they’re never able to get 100 percent of the plan.

Pretty much on a weekly basis — sometimes in crunch times on a daily basis — I was in touch with the director or the DP to say, “What do we absolutely have to have? We’re wrapping out of this particular location.”

For that budget level, you never have the luxury of going back. Even things like “what’s your wish list?” and as that wish list gets smaller and smaller things like, “Please get me a night exterior for this just so we have it in case we need a transition.” “Please give me a daytime exterior.” So we were constantly in dialogue.

I was sending him scenes pretty much at the end of every week. Pretty much I was always up to camera but maybe not every scene that they shot by Friday but sending him enough scenes to give him a sense of where he was — not just in terms of planning but I think emotionally it was important for him to feel like “OK, we’ve got a film. The performances are as genuine as I feel that they are. There is a chemistry that’s happening in the family that we see on set but it’s translating to the screen.”

Obviously, the dailies cut scenes aren’t perfect in terms of what he wants but I think there was enough there that it gave him a sense of: “OK well we can keep doing the things that we’re doing and the compromises that we’re having to make aren’t hurting the film.”

I think that that buoyed his spirits while they were shooting. We made adjustments, too, in terms of what do we have to have? What can we cut? How can we simplify the blocking of this particular scene so that it’s three setups instead of five? That type of thing.

It was wonderful to be in dialogue with Isaac in that way through the shoot.

HULLFISH: And did you feel — because of that truly important need to wrap out of a location — during dailies – that you needed to edit in a certain way to make it faster so that you were more confident that you had what you needed?

YOON: I don’t know if I needed to move faster than felt comfortable in a way just because they were being so aggressive with schedule and were so budget-constrained, I never had an overwhelming amount of dailies, and I could see by the decisions that Isaac and his incredible DP, Lachlan Milne, were making, what they were after.

So it helped me to sort of get to a pretty good cut quickly because I didn’t have to kind of wade through two or three cameras worth of footage for any particular scene, so I didn’t have to rush.

Because of the way that they were communicating through their setups and where they landed at the final take were pretty clear that I got to a cut pretty quickly. There wasn’t a lot of ambiguity.

HULLFISH: Were they shooting multi-camera? It looked to me like it was truly single-camera, but you never know.

YOON: Yeah, it was single-camera pretty much on everything except for some of the set-piece scenes that you see towards the end.

HULLFISH: Just the composition and care, felt very designed for an angle.

YOON: I was so impressed from day one. You felt like the amount of attention and desire to elevate the material coming from Isaac and Lachlan’s shot design. There was a real confidence there, and I think part of it comes from the fact that this is Isaac’s fourth or fifth feature film that he’s done. There isn’t that unnecessary experimentation. There isn’t that: “Oh I have to get this safety angle,” et cetera. There was a real confidence that I saw in the dailies which was great.

I think what Lachlan brought to the table is just that he had such great instincts for making the frame look like so much more than our budget. It was like magic.

I’m not a DP, so I don’t know what lenses they were choosing or what combination of camera and lenses but it just really elevated the material. They were simple, beautiful decisions that they were making that just created a gorgeous frame.

I couldn’t believe that they were doing it with the time that they had and the budget that they had. It just really excited me. They’re really bringing their A-game. It inspires you to work that much harder to honor that effort that production is doing.

HULLFISH: One of the very first things I noticed about the film was a definite sense of perspective. I felt like the cameras were always kind of low. I guess it’s kind of the autobiographical thing is from the child’s point of view, right? More than the father.

YOON: Very much. That’s a wonderful observation because the script began as a series of journaled memories that Isaac had about his childhood and what prompted him to begin that process of recalling these moments was that he became a father and he was looking at his daughter and thinking, “What is she going to recall?” But also, “What can I tell her about what my life was like at this age?”

He collected these poignant and funny and sometimes tragic memories and that formed the backbone of the script. And so the fact that that’s translating onto the screen is, I think, a testament to his qualities as a director — to be able to convey that perspective even though young David, his proxy onscreen, isn’t in every scene, I think that point of view is the lens through which we see all these characters.

It’s kind of a double vision in a way because there’s no way that young David could have the level of maturity to see the nuances of what’s going on with his parents. But that’s kind of the perspective of older David or Isaac in looking back.

He can see how fully fleshed-out their issues and their problems are — their goals and dreams in a way that we often can’t when we’re young and we can only see once we’ve achieved adulthood as well and sort of can empathize in a deeper way. So I feel like you get both of those perspectives and it’s moving to see the grace with which you can view both the virtues and the flaws of the people you love the most.

HULLFISH: As you said, the boy couldn’t have seen everything. There were discussions and arguments and difficulties that his parents had that he wouldn’t have been privy to, but I think that as it’s an autobiographical film, he knows his parents well enough, he knows the outcome of what happened in their lives.

YOON: Exactly.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about performance and how you judge performance when you’re looking at dailies because the performances were so honest and just real to me. I absolutely did not feel like I was watching actors.

YOON: It’s wonderful. First, you have the luxury of some incredible actors. For example, Yuh-jung Youn who plays the grandma — I’ve heard her referred to as the Meryl Streep of Korea. She’s a legend in Korea.

When I was telling my parents who was in my movie they said, “We think we know Stephen Yeun.” Then they said, Oh! Yuh-jung Youn! She’s in your movie? Then it’s a real movie!”

Then you have someone like Yeri Han — who plays the mom who’s so incredible and just so embodies that outwardly gentle but inwardly steel quality that so many immigrant moms have.

Then the kids are incredible. And Steven just brings such depth and understanding to his character, because I feel like he’s witnessed it. He’s witnessed what that father goes through, perhaps in watching his own father.

You have the luxury of beginning with those performances but I think the most important thing was that both in Isaac’s direction and in the choices we were making is that we wanted to keep all of the sincerity and all of the truth and no more. Right?

So we’re constantly looking for those moments where it wasn’t too much and pulling back and letting the way that the actors were embodying the characters versus maybe a too on-the-nose line or too strident a gesture or something like that — to pull back on those things and just have enough of the performance and no more.

I think that’s what Isaac was striving for especially in directing the kids because I think that’s such a subtle thing. Especially the more experienced the kids are, the more they can kind of go into particular gestural things and schticky things that they know work.

HULLFISH: Schmacting.

YOON: Yeah. Exactly. He was so good about putting them in a place where they could respond emotionally.

For example, in the scene where David’s being punished for something terrible he does to his grandmother. There was a seriousness with which all the actors — and Isaac as a director — were talking to Alan (David). Not in any cruel way, but instead: “This is very serious!” There’s a tone that they were taking to just get Alan to sort of come on board to feel, “Oh man. I really have to be on my best behavior. I really have to be contrite.”

And even between takes they kept up that atmosphere, so I think they were really good about creating opportunities where the actors could be really in the moment and in these characters versus having to play them out, and that made it easy to choose best performances.

HULLFISH: One of the things that I would be interested in hearing you talk about is the grandmother and the tone of her performance and not letting it go too far. She’s kind of comic relief. And what a great character. I told my wife, “She kind of reminds me your mom.” Her mom taught our kids play poker.

YOON: I think that’s why she feels so real. She’s not the idealized vision of a perfect angelic Grandma in the cultural mythology. But someone who’s as real — with idiosyncrasies and bad habits and things like that.

The fact that she watches too much TV. She watches pro wrestling instead of paying attention to the kids. She’s not the great cook that everybody expects her to be. I feel like Yuh-jung Youn knows that person. She actually has had a really unconventional life for a Korean actor of her generation and has come up on top of a lot of tragedy in her own life. So I feel like she embodies that resilience, but resilience after making choices that are unconventional choices. She was able to really embody that character and knew that character.

What’s amazing is that she’s such an experienced screen actor — even though she’s just living the character — she’s always aware of where the camera is. She’s always aware of the timing of a particular scene. Not just comic timing but if the camera’s moving, where is it? If the camera is behind her, how do I adjust my performance?

It just felt right every time and I think that that’s just a testament to her level of experience and her gift.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about the evolution from your first editor’s cut to where the film ended up.

YOON: I think we had a really strong cut out the gate — the editors cut. And I think it was a good evocation of the script in its entirety.

One of the things — in looking back at where we ended up with the film — was it was very clearly a process of removing good things — things that were working — that didn’t serve to focus the audience’s attention on what became very clear was the story, which was really focusing on our family.

In telling the story of the family there were moments in the script — and that were shot — that were forays into the world in their town outside of their family, so with secondary characters, really fleshing out “what is this world that they’re interacting with?” particularly the non-Korean characters in the movie.

One of the things we found was — as rich and as successful as those second storylines or those little detours were — they had a positive effect of fleshing out the town and the world and the completeness of Isaac’s memory, but they distracted a little bit in terms of our attention and our focus on some of the subtle things that the family members were going through at the time.

So because it’s such an elliptical script — you’re jumping from incident to incident to incident — and you’re not always sure how much time is going past in this family’s story, there isn’t a ticking clock, there’s not something that tells you, “it’s now three months later or six months later.”

We found that it was really important for the audience to connect the emotional dots of: “this is how David is experiencing the frustration of his father” or “this is how it’s really landing on the wife of what is happening with the farm.” And we found that the more we took out some of this additional bonus material, the more it really kept you emotionally in tune with what was going on with the family.

So that was the process, but it was hard to see that initially because so many of these sequences in and of themselves were so good.

There’s actually a bike scene that you see in the trailer where the two kids are kind of yelling out as they’re riding their bicycles. That was one of the last things that we cut because — on its own, it was hands down one of the funniest, most exultant scenes that we had — but that moment, and where it landed in the film and how it distracted us emotionally and took us down a totally different emotional path, worked so well but it sort of distracted us from where we should be in the overall calculus of tracking where the characters should be, emotionally.

So that was really eye-opening for me. It reminded me again how — particularly at that late stage in a feature cut — so much of it is about taking things away rather than adding. So much of it is about trying to get to that perfect geometric proof which is one step less in the proof so that you can achieve the elegance that you want the audience to feel.

And that’s a lot of what the process was. Asking Isaac’s permission and then all of us agreeing based on audience feedback and our own analysis of that. What else can we take away? What else can we remove to make what’s left even more muscular and the architecture that much more elegant?

And I feel like we got to a really good place where we all felt very confident in those decisions. We’re very excited for people to see deleted scenes because there’s a couple of scenes that are pretty great.

HULLFISH: It may seem like we’re done with that topic, but I am really fascinated with it because I think it’s going to hold some good meat for editors to think about.

This scene which you’ve described as being a really good scene and it’s going to go and I am fascinated by what the discussion would have been. And if you can — without revealing too much about the movie — how was that scene taking it in the wrong emotional direction for what happened next when you took that scene out?

YOON: It’s really interesting because that scene was singing so well — in fact, it broke all of our hearts because our incredible composer, Emile Mosseri, just wrote an incredible piece of music. It was just singing. We just loved it. Even in screenings, we are all looking forward to that scene.

HULLFISH: So how does it get cut out? That’s crazy! You know, I understand it though.

YOON: So the only way is to do it and to see it and to see it with an audience. What was great about Isaac was that he was fearless about trying things, because when we were making the decision to take it out we weren’t sure. In fact, for a long time, we had to sit with it and that’s the kind of scene where you have to re-watch the whole movie.

HULLFISH: Yeah. You don’t just back up five minutes.

YOON: Exactly. Because it’s much harder to calculate the impact of an absence than the impact of an addition. So you can sort of make very good arguments before you watch it and experience it as to why we need to ADD this piece of information or this emotional data point, but it’s much harder to get the total calculation of what an absence feels like and so you have to watch it. You have to do it and then see what results.

But what was really lovely was when we did do it — along with some other adjustments in that area — when you juxtapose things that weren’t juxtaposed before those kinds of collisions create really interesting emotional impacts that you didn’t see before. Even visual impacts.

There were things where we took out a big chunk in that sequence and then all of a sudden the lighting of a tooth-brushing scene and the lighting of a scene of the mom in the hospital — boom! Those two scenes — and actually even the ways that the characters were moving — we’d never seen that juxtaposition before.

It’s as if we planned it to say, “See how these people — even when they’re separated — they’re kind of connected by gesture and lighting and things.” And so there are ways that those collapses create those beautiful moments.

A lot of a friend of mine was one of the additional editors on Terence Malik’s Tree of Life and her job was to come in at night and literally randomly lift out sections from other editor’s timelines to see if there are interesting collisions that happen of dialogue, voiceover, or picture. She would save those as sub-clips to show the editors the next day.

So there is a way where that process can be so creative that really experienced filmmakers like Terrence Malick rely on that to take us out of our presuppositions about what’s there — even in the material that we have. So that’s what convinced us. Not necessarily, “Oh, we don’t miss it” but it was more like “Oh my gosh! We didn’t realize it would have this impact! We didn’t realize that it would really help this other thing that we were trying to do.”

Bottom line, I think the practical takeaway from that is you have to try everything because there will be results from the removal that you are not anticipating. To me, that’s why I love editing so much. You’re always the first audience to see something magical when it happens.

As smart as you are, as experienced as you are, that surprise juxtaposition and the way that your brain creates meaning out of it is like magic. That’s the thing that I think makes it so special as a process.

HULLFISH: I was just having a conversation with my brother — both of our kids our engineers — and his son said, “I always feel bad because I never come up with the answer the first time.” And I said, “We have these discussions about editing all the time and almost nobody comes up with the answer the first time and sometimes it’s coming up with the wrong answer that gets you to the right answer, and you couldn’t have gotten there without going through the wrong answer.”

YOON: Completely. And I think the really important observation that really helps us to get to that place is, “Let’s try to get as much of our ego out of the process as possible.” If you’re upset that you don’t get it the first time because you feel like your identity or your ego depends upon that….

HULLFISH: Identity and ego. 100 percent.

YOON: But if you practice a kind of creative humility then it’s OK. However, which way you get there you’re going to get there. But if you’re fighting it tooth and claw then you’re not. If your ego and your identity depend on your fighting for a particular cut or a particular fixed way of looking at a scene or a sequence, then you’re sort of robbing yourself of the opportunity for those creative moments and you’re robbing the project.

HULLFISH: What was the emotional throughput or emotional arc that that removal helped keep clean?

YOON: The strongest arc that it reattached in a way was keeping the young boy’s POV about what was happening with his father at that time. That visit to his friend’s house happens relatively late in the film where you’re starting to get a strong sense that the farm is not doing well.

When that sequence became about David’s exploration of the outside world and his friend’s strange and crazy customs that were so different from the Korean customs he was used to — it was a nice counterpoint emotional beat to what was going on. And also it did give you a sense of David’s innocence in what was happening.

But I think in making it less big of an experience for him — even though when he was over at his friend’s house — it kept him emotionally thinking about what was going on back at home. And that was most visible in the breakfast scene where he spends the night at his friend’s house and then the next day when he’s at breakfast with his friend’s father-figure — it’s actually his mother’s boyfriend, but for all intents and purposes it seems like his dad.

That scene used to play out with a couple of other really important details that gave you a stronger sense that that father-figure was abusing his son. Not just strange but a little dangerous. And that implication — as well as the bigness of the emotion that you used to have — distracted you from what was being said at the breakfast table, which was this conversation about: “How is your dad doing on his farm?”

But the whole time you’re just wondering, “Is he going to hit David or is he going to do something weird or rash or something like that?” Whereas if you take that away and you also take away the distraction of being in another world, his questions really point David emotionally back to thinking about his father. Like, David actually maybe hasn’t even articulated: “How is my father doing? How is he doing on the farm? Is he OK?”

And I think it’s exactly what you were talking about at the beginning of our conversation where you really feel such a strong sense of David’s perspective and that’s what emotionally anchors the film. And in removing a lot of those nuances, we really refocused the audience’s emotional focus on: “How is David feeling about this?” I think that leads into a more contemplative sequence where you start to see — physically and emotionally — the toll that it’s taking on his father and on his parents.

It was a much clearer transition emotionally in the story that we hadn’t had when that sequence was bigger, longer, and with all these other details.

HULLFISH: That’s so interesting. So, where did that bicycle scene happen? The bicycle scene and the breakfast scene obviously must come close together. Where did they happen in the film?

YOON: There is a moment when Mom asks the kids to spend the night over at their friend’s house because Grandma is in the hospital. That’s when that whole sequence took place. When David goes to spend the night over at his friend’s house.

HULLFISH: I love all that. What else do you want to talk about with this film? Were there challenges? Structural things that had to change? It seemed pretty linear.

YOON: There’s one thing that I think really stands out for me editorially — the impact that Emile Mosseri’s music had on our process.

I was lucky enough to hear some of Emile’s music (because he did the score for Last Blackman in San Francisco) and for that show, he created one of the most gorgeous scores I’ve heard in a long time in record time — on a really impossible deadline. So it just really spoke to his talent at narrowing in on profound emotions with limited resources and limited time.

What was great, for Emile, was that he was in conversation with Isaac during preproduction, and because his partner Allie was from Tulsa they actually got to visit the set and see what that set looked like and feel what was going on with the family and to really get insight into it.

Even before they shot, Emile wrote a couple of sketches based on the script and on his conversations with Isaac. Isaac would listen to some of those sketches as he was driving to set and I listened to the sketches before I cut a frame.

You know how music operates in you in different areas of your brain and your emotions? I feel like there was a story, there was a tone, that Emile was downloading into our brains and I feel like infused what they were shooting and infused the editorial direction and the tone of what we were cutting.

It found this really beautiful expression — I used one of his sketches to cut together a wrap party gift for the crew to thank them because they had worked so hard to put together such beautiful footage in spite of really challenging circumstances. And it was a chance to share that melding of everything that the crew had done with this incredible, beautiful music. It brought tears to a lot of people’s eyes.

This is one of those rare instances in which everybody has this sense of what true north is on this film. And it’s really brought us together with that common purpose and it’s been rare unfortunately for a composer to be able to have that kind of influence because they’re often brought in so late in the process. But in this film, in particular, you saw how powerful that could be in shaping Isaac’s experience of production and my experience early on in editorial. I’m really, really excited for people to hear this score.

HULLFISH: Can you describe the score? It really was kind of magical. I loved the music I’m surprised that I didn’t bring it up myself, but I just forgot.

YOON: It’s sort of lush and sweeping but with voices that feel unusual and feel more like a memory than fully present and there are ethereal qualities that he uses like a tiny bit out-of-tune piano. It’s like this older piano that he uses. He’s a singer-songwriter in his own right, so he has this gorgeous falsetto that he records and overdubs. You hear a voice that’s been transformed into this falsetto chorus as an element in the film.

All of these unusual elements give you a sense of other-worldliness and yet it’s still grounded in these beautiful melodies and themes. It just feels familiar in its emotions but unusual enough and fresh in its instrumentation and orchestration that it feels new. It feels like you’re rediscovering something that feels true.

HULLFISH: Any other thoughts on the film?

YOON: I’m really, really excited that there’s awards buzz and things like that. You kind of dream about that and you dream about it because it’s always out of your control, especially as an editor. It has to do with the project and the gifts of your collaborators and the vagaries of taste and whatever is of the moment, and all those things are so out of your control.

But I think what really was personally meaningful for me was that first screening in the Library Theater at Sundance in our premiere and I was lucky enough to sit in front of all of these parents — Steven Yeun’s dad and Isaac’s parents and Christina’s parents.

You know how — in certain audience screenings — you can feel the emotion from behind you and the hairs on the back of your neck kind of stand up and you think, It’s working! People are responding and to know that the parents were seeing themselves and they were so moved by being seen. That’s what I feel has been the gift of this movie.

What I’m most looking forward to is when it’s possible — hopefully soon — I just want to buy out a couple of rows in a theater for my parents and their friends and all the people we kind of grew up with and just get them into the theater to watch this movie because I think it’s just so rare when you get an opportunity as a storyteller to tell a story that’s so intimate that you know the people that you love and are really close to you will be able to really appreciate and to feel seen.

That’s what I’m most looking forward to — beyond any awards or beyond any accolade — it’s that screening and (the possibility of) that moment that I just feel so grateful for.

HULLFISH: If this was more of a Crazy Rich Asians movie I wouldn’t ask you how your personal voice as a Korean played into being able to be an artist on this film but with this emotional personal storytelling, I WILL ask you that. How important was it for you to just be you?

YOON: I think my personal experience is what allowed me to gel and to find common ground with Isaac, the director. It’s what connected Christina Oh, the producer, and I. That was on a different project, but us being able to say, “We have this in common and we can understand this in a way where no translation is necessary.”

I remember screening a scene for our post supervisor and he said, “That’s great. I wish I knew what they were saying.” That’s when I realized, “Oh wait! You need subtitles!”

HULLFISH: (LAUGHS).

YOON: We’re cutting in Korea the whole time. It’s a mixture of Korean and English and I was so deeply involved in it that I forgot that somebody is not going to know what they’re saying.

HULLFISH: That is not a foregone conclusion that someone of your generation would speak Korean.

YOON: Yeah, exactly. Because a lot of us are first-generation immigrants. I was born in Korea and I came here when I was five years old. English was my second language although it’s my primary language now, having forgotten a lot of Korean. But thankfully I know enough where I could understand the majority of what was being said.

Practically-speaking, that biographical connection to being Korean-American and to being an immigrant was important, but I think emotionally I feel I could really understand moment-to-moment what the characters were going through and what Isaac was remembering through these characters because I had lived a lot of these moments.

When you grow up with immigrant parents who are small business people you see a lot of that conflict, and you see a lot of that pain, and you see the roller coaster ride of emotions, the loss of dignity the conflict that happens when both parents have good intentions. They’re doing it for the right reasons but they’re colliding because practically there aren’t enough resources or time or luck in order for both peoples’ desires to be manifest.

I think I knew that very intimately and so I think it gave Isaac and me a shorthand, being able to get at the essence of certain scenes and hopefully get at the essence of the movie in general.

HULLFISH: Honestly, my recollection of this film is almost every scene is a oner. I know that’s not true. I know that’s not true, but the scenes are cut in a very limited, disciplined way. Congratulations to you.

Do you find that you cut them too much at the beginning and came back or did you start at that position and think from the beginning, “I’m not going to cut. I’m just going to sit on this great composition and these great performances and this is where I’m going to stay until I have to go someplace else?”.

YOON: I think there are slightly different styles from scene to scene.

YOON: I think there are slightly different styles from scene to scene.

HULLFISH: Oh yeah! I mean the big scene at the end, obviously, is fast cut.

YOON: For example, the way that he shot the scene where Paul is walking through the house, anointing it with oil and saying these prayers — just sort of exorcising the demons that are around — that was shot in a very verite, documentary-style whereas a scene like his wife washing Steven Yeun’s hair, that was shot in a much more beautifully composed wide shot and then only cutting in for certain grace notes of emotion towards the end.

But I think in general, because we were given the gift of beautiful frames a lot of the time, it was easier to hold because there was a lot of visual interest.

And I also want to bring up the incredible work of the production designer Yong Ok Lee who infused every frame with such interesting things — and not just interesting things — things that felt so true that I often felt like, “Oh my gosh! I’m looking at MY house.” My mom had that exact same wall hanging.

I think when you have somebody who is creating beautiful frames both from a cinematography standpoint and from a production design standpoint — costumes, you name it, everybody is doing good work — I think it’s easier to hold. And obviously, the actors are doing great work.

I think, for the most part, it was to allow us to live in the moment and live in the performance and then to only cut as needed unless it was something that was shot more verite and should feel more dynamic and of-the-moment. Or a sequence that’s designed for more kinetic action, like towards the end — that sequence, that type of thing.

But, for the most part, it was to hold on these really beautiful frames.

HULLFISH: I love it. Congratulations to you. It’s a great film And as much as it’s about a Korean-American family, it’s also a very universal story with universal characters.

I just had discussions with my wife where I felt like this relationship with the husband and the wife — this could be me. It’s completely universal. It’s a very universal story of a family.

YOON: That’s what I’ve loved. I have a Latino friend that said, “Yeah, I used to watch wrestling with my grandma too.” You would think that would be a weird detail but when you get specific in that way, people think, “Oh my gosh. I recognize that.” It feels truthful.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed, and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now