Walter Murch, ACE, has edited for more than six decades on more than 60 films and more Oscars, Emmys, Eddies and BAFTA awards than I can mention. Just go to his imdb page and save me some time.

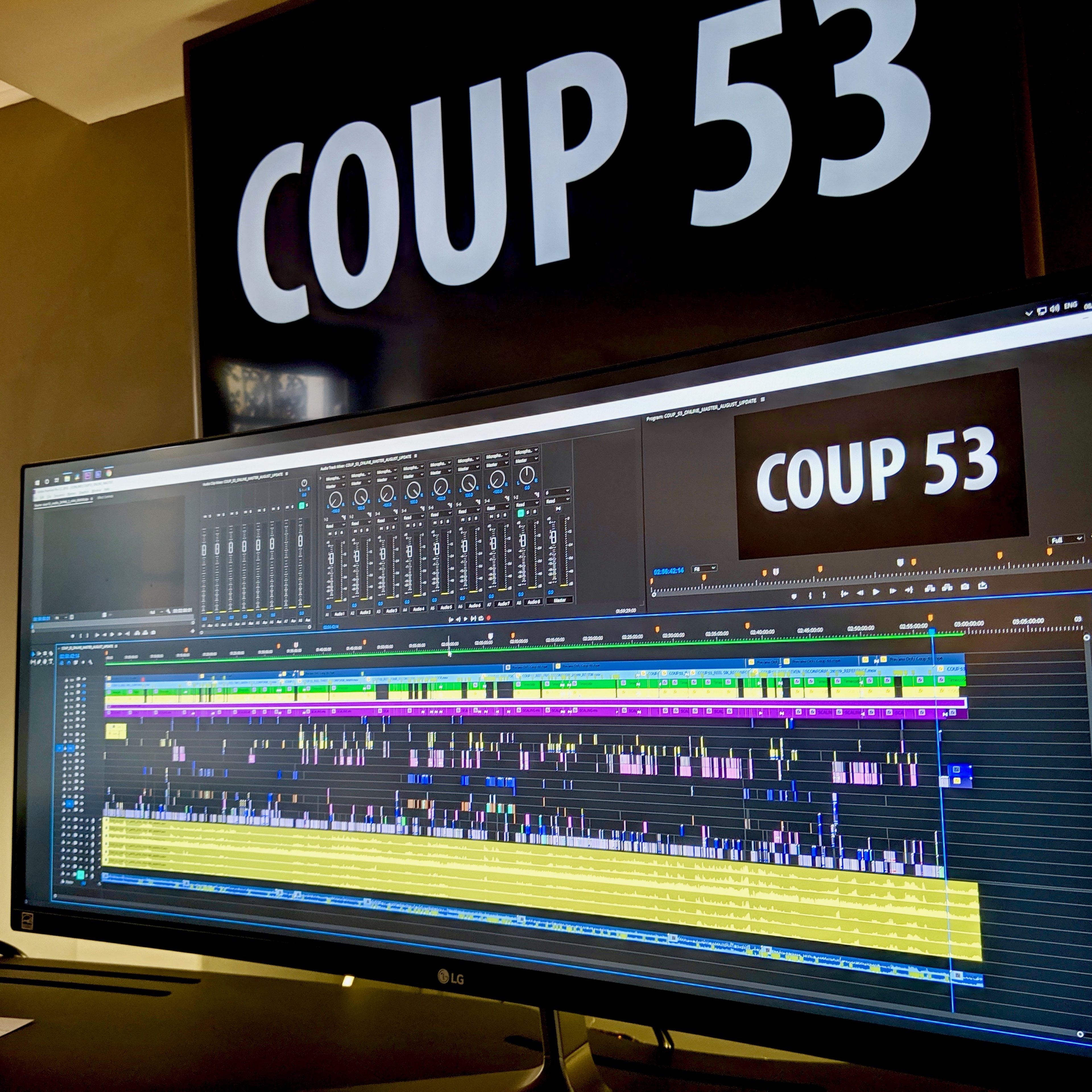

I sat in a screening room in San Francisco with Walter before watching the documentary he edited, Coup 53. In a previous interview, Walter and I already discussed that film. In this interview, we discuss some follow-up questions about his book, “In The Blink of an Eye” and his book with Michal Ondaatje, “The Conversations. In the upcoming weeks, I’ll post additional interviews in which Walter and I discuss five films that he suggested I watch before our interview. We’ll also do an interview with questions asked by the members of the Blue Collar Post Collective.

This interview will be available as a podcast. The podcasts with Murch will not correspond to the same text articles on Murch. Eventually, all will be presented as text and all will be presented as podcasts, just not in the same release order.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

MURCH ON THE VALUE OF BREVITY

HULLFISH: You said, in Michal Ondaatje’s book “The Conversations,” (a series of interviews he did with you): “The hallmark struggle of every editing room: how short can the film be and still work?” Why do we want to make films as short as they can be?

HULLFISH: You said, in Michal Ondaatje’s book “The Conversations,” (a series of interviews he did with you): “The hallmark struggle of every editing room: how short can the film be and still work?” Why do we want to make films as short as they can be?

MURCH: It’s not unique to film – the same struggle goes on in writing a novel, or a poem, or a piece of music. The German word for poetry is Dichtung, meaning compression. But with film it’s also got something to do with the ability of people to sit still for a couple of hours. If you put somebody in that chair — we’re sitting in a theater — and said, I just want you to sit still for two hours without any other distractions, it would be almost impossible for them to do it. They quickly start to fidget.

But what happens when a film is working is that it’s hypnotizing the audience: they’re not really “in their body” anymore. That’s the whole reason for Harry Cohn (the head of the old Columbia Studios) saying, “When a film doesn’t work, I feel it in my butt.”

What’s happening is he’s not being hypnotized, and so he starts to realise the obvious, which is he’s being asked to sit still for two hours and he can’t, so he starts to fidget. Cohn didn’t go into that kind of detail, but I think that’s physically and neurologically what’s happening.

And yet there are still absolute limits to the hypnotisation, physical limits. It seems like it’s somewhere around two hours, maybe two and a half. When a film gets over two hours, it begins to turn into something else. I just think it’s a mixture of how much you can hold in your mind — even if the film is emotionally engaging. Also: how full is your bladder?

FEELING A SCENE IN YOUR BUTT

HULLFISH: In “In The Blink of an Eye” or in “The Conversations” you talked about screening Julia. When you go those screenings with an audience, is that one of those things that you’re just inherently looking at — people are moving?

MURCH: It’s interesting that we don’t photograph the auditorium with an infrared camera, which would be a great learning tool. You – the editor – have been alone or with a director in an editing room for months, developing your own theories about how the film should be. But now you’re experiencing it in a large auditorium with maybe two hundred and fifty people and that puts you in a very different emotional place. It’s a good thing, really, because now you’re looking at the film from a different perspective – the imagined perspective of those 250 people.

If you think of the film as an architectural model, it’s as if you’ve always been looking at it from one angle. What a preview does is emotionally move you 90 degrees off-center. And so now you’re seeing the 3D architectural model differently. “Oh, that’s where the staircase went.” As obvious as that was, it was just something you didn’t realize when you were alone with the film.

You try to anticipate what the public is going to think and feel when they see the film. You try to put yourself in their shoes. But everyone has blind spots, and you can fool yourself about things, about where that staircase actually goes, so to speak. But a preview really forces you to confront those blind spots. It’s an almost hormonal experience. Anthony Minghella described it as being made “skinless” – unprotected.

HULLFISH: I’ve done two interviews recently with people that did say they filmed the audience with infrared. The last one was for Zombieland: Doubletap.

MURCH: Oh, really? Amazing…

HULLFISH: Yeah. And then they synced the infrared video to the movie in the timeline as picture-in-picture, so they could judge the reaction while they were editing. The editors I’ve talked to that have done that are mostly working on comedies or horror.

DOES CONTINUITY MATTER?

MURCH: On Ghost, I recorded the audience in the final preview, and in the mix we were able to play that audience track through the monitor speakers, along with the final mix. if you’re mixing in an empty movie theater, you may think a line of dialogue is clear, but if 300 people are laughing, you have to push the loudness to compensate. To surf over the laughter.

HULLFISH: You mentioned Anne Coates, Dede Allen and Thelma Schoonmaker are all in the list of 10 of the best editors in the world. And Raging Bull is certainly one of the great works of editing. What do you think it is about their talents or that film, Raging Bull, that is worthy of that consideration?

MURCH: The common thread there is that they are all women. In the early days of film, the silent days, there were lots of women editors because editing was seen as a kind of sewing, and film as a fabric. There are also similarities between the film as a library, and a lot of women were librarians. So it seemed natural to hire them to be editors.

That began to change when sound came in. Editing got technical in a non-feminine way – whatever that means – and so men began to become more dominant from that point on.

There’s that great answer from Thelma where an interviewer observed, “Marty’s films are so violent” and she said, “They’re only violent after I edit them.”

HULLFISH: For me, one of the things that I thought might lead you to that is that Anne and Thelma — and I’ve interviewed both of them — agree with your thesis that continuity is the least important aspect of the six things that you say need to be considered when making an edit. Anne and Thelma are certainly in that camp — being less concerned with continuity when other factors are more important.

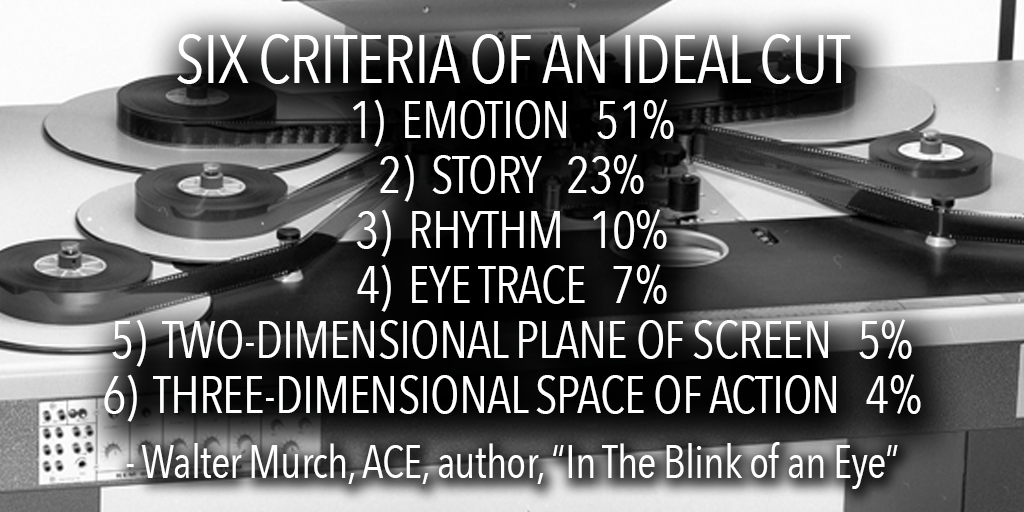

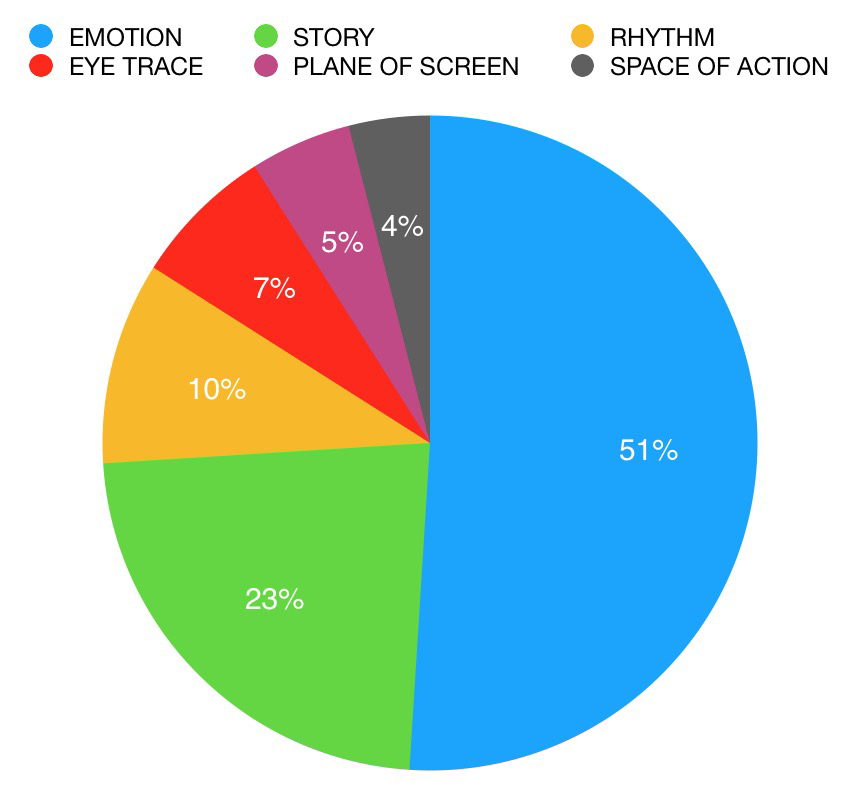

MURCH: That’s the main point of my Rule of Six in the book “In the Blink of an Eye”. Emotion, Story and Rhythm are the top three – with Emotion at the very top – and issues of continuity are at the bottom – with three-dimensional continuity at the very bottom.

In some abstract world, every cut would tick each of those six boxes. But we don’t live in that abstract world, nor would we want to. And since we live in the real world, to make every cut work you’re going to usually have to let go of something. And my recommendation is to let go from the bottom of the list up. Let go of three-dimensional continuity first and then work your way up. After that, if the only way to make a cut “work” is to abandon two-dimensional continuity – the 180˚ rule – then, by all means, do that. But when you get to the top three – rhythm, story, and emotion – by all means try to hold on to them.

In some abstract world, every cut would tick each of those six boxes. But we don’t live in that abstract world, nor would we want to. And since we live in the real world, to make every cut work you’re going to usually have to let go of something. And my recommendation is to let go from the bottom of the list up. Let go of three-dimensional continuity first and then work your way up. After that, if the only way to make a cut “work” is to abandon two-dimensional continuity – the 180˚ rule – then, by all means, do that. But when you get to the top three – rhythm, story, and emotion – by all means try to hold on to them.

If you have to sacrifice one of those top three then sacrifice rhythm first. But only if doing so preserves a powerful emotional impact and story sense. If you have to let go of story for a moment and just go with pure emotion, do that. But it’s risky – you can’t stay in that zone too long – you have to get grounded in story as soon as possible. It’s kind of like those training flights which allow astronauts to float within the belly of the plane, so they’re weightless for forty-five seconds or so, but they can’t stay there long. Gravity has to exert its force again. Story has – or should have – a kind of compelling gravitational force to it.

HULLFISH: I’ve heard you say that the numerical values you placed on those is a little bit facetious. But in reality, it makes sense because you’re like, well, the top one, emotion, is more important than all the rest. So you gave it a value of 51%.

MURCH: It’s more than everything else.

MURCH: It’s more than everything else.

HULLFISH: Right.

MURCH: I had to make the numbers jump around to achieve that effect!

HULLFISH: I totally understand the numbering system. And while we’re on this, there is one of them that I do not understand, which is 2D continuity. Explain the difference in 3D continuity and continuity in 2D.

MURCH: 2D is just the 180 degree rule – the problems that arise from translating a three-dimensional reality – life – into the two-dimensionality of the screen.

HULLFISH: Ok, got it.

MURCH: When you first begin to study film, you have to make your brain do something strange because we live in a three-dimensional world and yet we’re not overly conscious of this because we’re always looking through our own “camera” so to speak. But when you have a two-shot dialogue scene, and then cutting to a reverse angle that is almost 180 degrees opposite to that, what you’re doing is taking a three-dimensional reality and compressing it into two dimensions. And we have just developed certain rules that, for the most part, we follow, to make it seem that the two people are looking at each other.

The simplest way to think about it is to forget all of the diagrams that get drawn and just imagine that there’s an invisible laser beam coming out from between a character’s eyes, which represents the direction of their “look”. And when you cut to the other person in the scene, imagine the complementary laser beam for them – their “look” and just make sure that those imaginary laser beams intersect, like clashing swords. Then the cut is going to work – it will look like they are relating to each other.

PICKLE YOURSELF IN THE FILM

HULLFISH: That makes sense. One of your quotes from “The Conversations,” in the section about Apocalypse Now Redux is: “One of the obligations as an editor is to drench yourself in the sensibilities of the film to the point where you’re alive to the smallest details and also the most important themes.” I love that. Can you elaborate on that?

MURCH: Well, I cringe slightly when I go into some editing rooms, and what the editor has put on the wall are the posters from all the other films that he or she has cut: it’s bragging, or so it seems to me.

But I understand why they do it: they want to feel at home, and they had a good time on these films. And the film they are working on makes them a little nervous, because of all the uncertainty that surrounds any project.

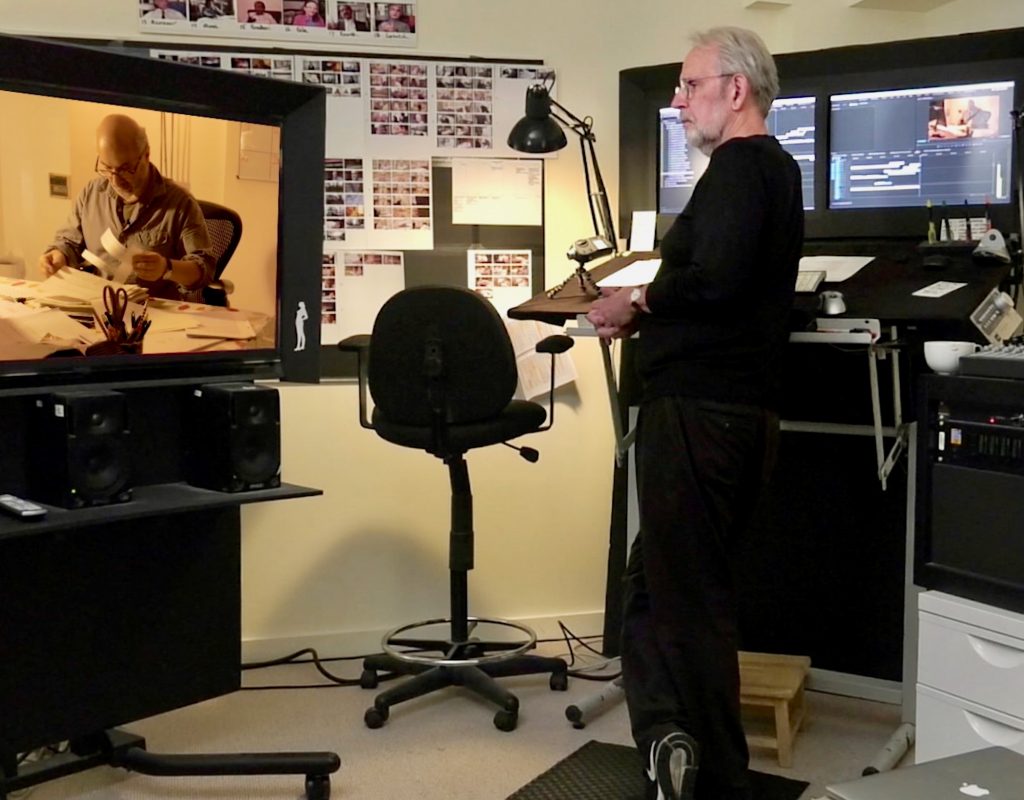

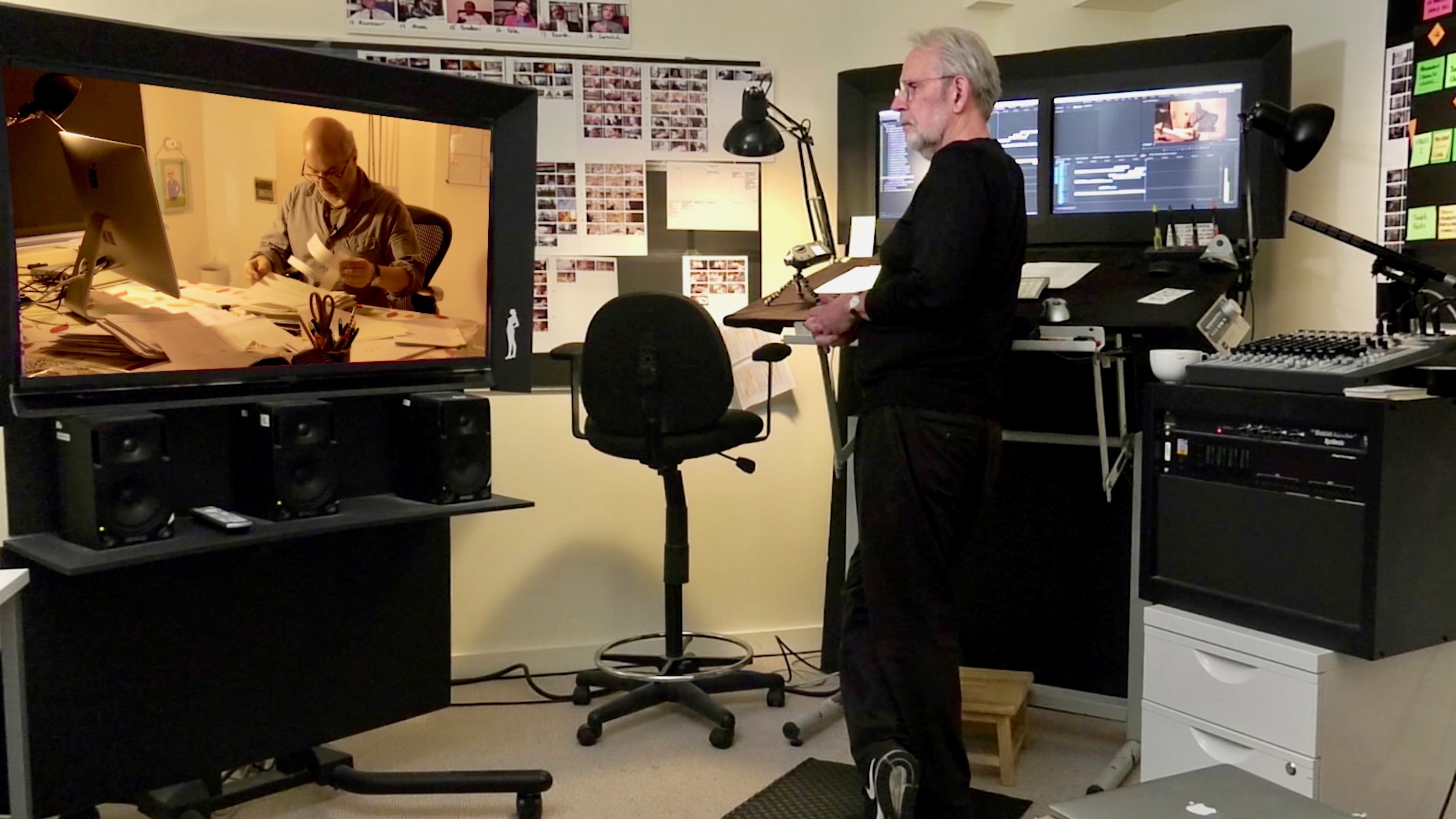

What I do instead is have panels of printed images of selected moments, frames, from every camera position in the scene that I am working on. So I’m either looking at the edited film on the computer or dozens sometimes hundreds of still images from that scene. It’s a way of getting a bird’s-eye view of the whole scene in a single glance. And it keeps certain moments from being overlooked or forgotten.

HULLFISH: I think there’s a lot of people that I’ve interviewed that have taken that methodology but nobody does it like you describe it — where you’re selecting frames from every setup.

I used boards on my last film, but it’s one shot from every scene. Not one shot from every setup, which I think it’s really interesting because it helps you edit scene. Whereas I think that cards that I put up helped me when I get to the story structure.

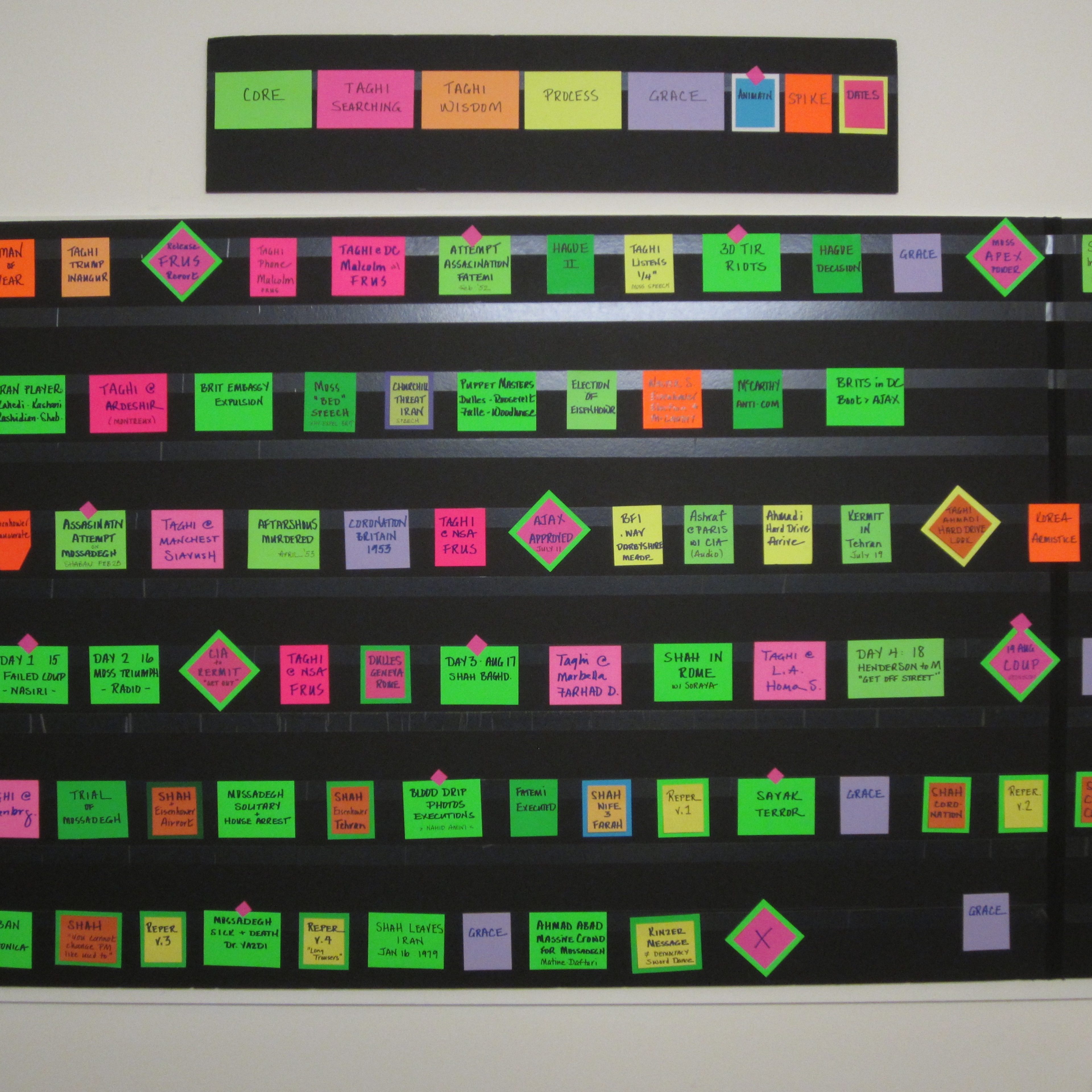

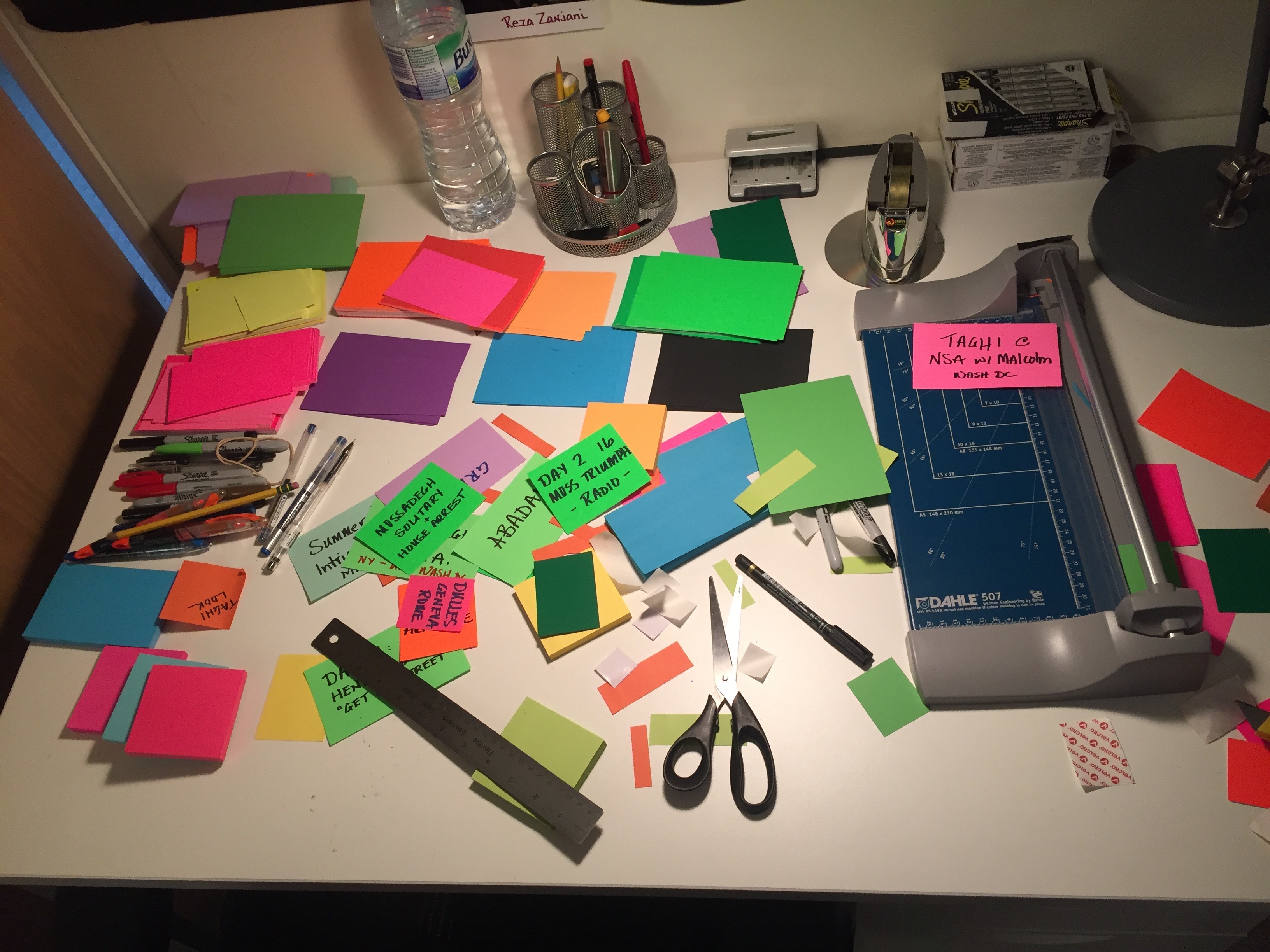

MURCH: That’s valuable. I use a card structure for that, but I don’t use an image from the scene. I just use different colors for every scene. The emotional tone of the scene prompts me to choose a certain colored card. And then I write five or six words, maximum, to get the idea of the scene across. And I also vary the size of the card, depending on how big a scene it is. And if it’s a really crucial turning-point scene, then I put the card at an angle, 45 degrees, so it looks like a diamond — which is to say, everything previous was building to this scene, and now it’s a pivot and everything after is different. It’s kind of like an elbow or knee joint in the body of the film.

HULLFISH: That’s kind of like a flow chart for a computer program. I do the color thing as well, so that I can see if there’s a big unbroken block of light scenes or dramatic scenes or action scenes.

MURCH: That’s very valuable. As a counter-example, imagine a wall of nothing but white cards all the same size. You walk into the room in the morning, and what does that tell you? Nothing. You have to read each card to know where you are. Whereas if you’ve chosen different colors and different sizes and different orientations, you learn something viscerally in an instant. “There’s too much blue in this section of the film!” All these graphic aids are different ways I use to “pickle” myself in the juice of the film.

PICKING UP WHAT THE DIRECTOR IS THROWING DOWN

HULLFISH: Here’s another quote from “The Conversations” in the Apocalypse Now! Redux section: “I sit with the director when we watch dailies. And if he has something to say about a particular moment, I note it, of course. But I also note other things as well. The mood in the room.”

You continue to say that what the director says doesn’t really help you too much — because there are so few of those notes, compared to all of the decisions in the film — but knowing what they think about THIS moment tells you about THESE OTHER moments, too. Correct?

MURCH: If the director scratches his head a lot during a scene, I will note that because that tells me something’s bothering him about the scene, even though he may say, “This is great,” but there’s some hidden dissonance there.

Anything you can use to help you distinguish this shot from all of the other shots, as illogical it might be, will work months later when you’re reviewing those notes. If for some silly reason you think “banana” write it down. Months later: “Oh, yeah! Banana! I remember that.” It puts you back in the moment you first saw the shot. There is only one first time, and it is important to preserve that feeling, which is as close as you will ever get to the feeling the audience will have when they see it.

The worst thing is simply to write “good” or “no good” because that doesn’t tell you anything much. And we all know that what was “no good” three months ago may be very good now because the needs of the story may have shifted and something that used to be ‘bad’ might be exactly the thing that you need now that things have changed.

HULLFISH: I remember that as a quote from one of the books.

MURCH: So if you think something is not working, write down why it’s not working, because that might be the very thing that you have to get back to.

MY WAY IS NOT THE ONLY WAY

HULLFISH: You mentioned that you’re surprised by the way other editors work sometimes, but it has to be extreme. Can you think of any of those things that you surprised you?

MURCH: I was on a panel many years ago with Richard Harris, who cut Titanic. And somebody asked, What’s unique about the way you work? And Richard said, “I cut from the end of the scene backward.”

So he figures out what’s the last shot of a scene and then asks himself: “How do I get to this shot, A? I’ll use shot B. How do I get to shot B? I’ll use shot C, etc.” It’s absolutely a unique and creative way of working.

Dede Allen would cut a scene’s dialogue — just like a radio show – without reference to the picture. And when she had it sound the way she wanted it, she’d give it to her assistant Richie Marks and ask him to put some picture to it. Of course, when he was done he’d give it back to her and she would take it from there. But it was a great learning experience for Richie.

I do just the opposite. When I’m assembling a scene, I do so without any reference to sound – I imagine what they’re saying. Of course, I’ve seen the dailies with sound and taken notes and I can lip read. But in a weird way, I don’t want to be distracted by the sound of the dialogue at that earliest stage. I deliberately make myself ‘deaf’ in order to concentrate on body language and facial expressions.

HULLFISH: It can affect your rhythm.

MURCH: Also, the dialogue track is not the finished soundtrack. It’s just the dialogue at the time of shooting — and with all due respect to the production recordists — there might be problems with the sound which can be distracting.

So by cutting it silent, by turning the sound off, I can imagine in some prefigurative way what the final sound will be. Even the music which hasn’t been composed yet. Of course, technically I am cutting the sound at the same time as I cut picture because it is there, muted, in the digital timeline.

So at a certain point, after I’ve assembled the scene and recut it a couple of times, still silent, I’ll flip on the sound and frequently I get very happily surprised by the accidental juxtapositions. I might have taken a reaction shot from later in the scene and used it earlier in the scene than originally intended, but it’s got the dialogue from later in the scene. And for some reason, it actually works. I fix what is obviously wrong and preserve the happy accidents, clean up the overlaps, etc.

I heard that David Lean cut without sound, and that gave me the courage to try it, and it turned out to work very well for me. But for Dede Allen, just the opposite. That’s the great thing about all this: so many different ways of doing things. Forwards, backward, sound only, picture only…

DON’T FIX IT WHILE YOU’RE STILL LEARNING IT

HULLFISH: Yeah. Joe Walker, who cut Arrival and Bladerunner 2049 and others does that often. He “cuts mute,” as he calls it.

You mentioned something that I appreciated because it’s a mistake I’ve made, so I appreciated this lesson from you, which is: If you try to correct the film while you’re assembling it for the first time, you end up chasing your own tail. So what’s the danger and what’s the problem with trying to do that?

MURCH: The evolution of each scene is unpredictable because of strengths and weaknesses, performances and the weather on that particular day: it was raining and they wanted sun, but they shot it anyway. Other things come into play, and the natural tendency of a human being is to say, “Well, that doesn’t work so well. I’ll think about how I can fix it.”

But you haven’t yet seen the finished film, everything is being shot out of sequence, and so your information is restricted.

Let’s say the first assembly seems to be rising up above the horizon, so to speak. And your tendency is, “Oh, I can push that down.” Well, unbeknownst to you, when the next scene is shot two weeks later, that scene does the pushing down for you, automatically. So you didn’t need to push it down, but because you pushed it down, now when you cut the next scene, that pushes things even further down.

HULLFISH: The whole thing’s flat.

MURCH: Flat or warped. So it’s like — as they say — pushing a piece of string. When cutting the first assembly, it’s what I call “cutting with your eyes half-closed.” Obviously, you have to make decisions. You can’t cut blind. On the other hand, you can’t — at that stage — apply all of your critical instincts because you just don’t know enough at that stage.

The classic example of that for me was in “Ghost,” where Tony Goldwyn is trying to seduce Demi Moore, who has just been recently widowed. The audience sees him purposely pour coffee on his shirt, and then he goes, “Oh, shit, I spilled the coffee.” And Demi says, “Give me the shirt I can wash it.” So he takes off his shirt, and now he’s sitting there shirtless, saying seductive things to Demi Moore.

When the studio executives saw that scene, what they saw in dailies was Tony Goldwyn shirtless over and over again in medium shots and close-ups and they got it into their heads that he wasn’t just shirtless, he was naked! It doesn’t make any sense, but they said audiences are going to think he’s naked. We can’t have that. And they went so far as to say he’s not even a good actor. We have to cast somebody else in the role.

It was kind of a fire alarm crisis. They wanted to get rid of Tony Goldwyn, who’s doing a perfectly wonderful job. It was one of those side effects of a studio executive looking at dailies. So I cut the scene together, and it’s fine, but there’s this crisis. And I was walking home one evening and I thought, Hmm, we could cut this whole scene out. I forget the structure of things, but there was a way of making it disappear without a trace.

It’s an important scene, but it seemed like a crisis. So I told Jerry Zucker, the director, we can do this and he said, “Okay, do it. Just to take the heat off for the moment.” And so we did it. And that kind of calmed things down. We had a solution short of recasting the main actor.

When we looked at the first assembly of the film, I had left that structure in and everything worked fine, but when it came to the end of the film, with Tony Goldwyn being dragged off by demons into hell, it seemed like, “Well, he’s being punished too much.” He was just a kind of hapless middle-class kid who got in over his head and something went wrong and his friend Sam got killed. It’s tragic, but he doesn’t need to die so horribly.

“His soul doesn’t need to go to hell” is how you felt at the end of the film. And it was just me and Jerry Zucker and Bruce watching the first assembly — Bruce Rubin, the screenwriter. After the screening, we were all talking about this weird effect, and I said, “You know, we were looking at this without the shirt scene. Let’s put that back and look at it again.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Y2wqkD2KVM

When we did that, it all made sense, because his crime was not to try to steal the money — of course, that’s a crime — but morally, his real crime was to try to seduce the widow of his best friend. That was the thing where he needed to be dragged down by these monsters.

HULLFISH: That’s a great example of a thing that happens with screening audiences. So often they’re actually complaining about one thing when it’s actually something else in another location that is causing the problem.

MURCH: That’s what, in medicine, is called referred pain. The pinched nerve in your shoulder shows up as a pain in your elbow. And the danger is that the preview audience will say “fix the elbow,” but the problem is not in the elbow. It’s somewhere else.

BE (MORE THAN) THE AUDIENCE

HULLFISH: Another quote from “The Conversations”: “You have to have an intuition about the craft, to begin with. For me, it begins with, ‘Where’s the audience looking? What are they thinking? What are they feeling’ as much as possible.” So my follow up question to that statement is: Do you think you need to be doing something more than just acting as the audience, as the editor? Are you just a surrogate for the audience?

MURCH: You always have much, much more information than the audience has. Ideally, I think what you’re trying to create for the audience is a sustained déjà vu experience. If you’ve ever experienced that, it goes along with an uncanny feeling: You don’t know what’s going to happen next, but when it does happen, you feel, “Yes, that’s exactly what happened.”

So the audience should not know where the film is going, moment to moment. They should be surprised, but as it develops, they should feel, “Oh, that’s exactly what should happen.” But you can’t ask them about that in advance because they don’t know. WE know, and so we’re always one step ahead of them, drawing them further along into the story. We’re trying to create a chain of self-evident surprises.

THE PERSPECTIVE OF MUSIC

HULLFISH: I love that answer. In the second conversation in “The Conversations” you say, “Where music makes an entrance in a film, there’s an emotional equivalent of a cutaway.” How do you think that that works as a cutaway?

MURCH: A cutaway is something that gives you a different perspective on the moment. A wide shot, for instance, or somebody else reacting. Or even the landscape through which the characters are walking.

When music comes in — if it’s well-written and it’s the right music — it also gives the audience a different perspective on what they’ve been looking at.

In Star Wars — after the deaths of Luke’s aunt and uncle — Luke is standing there looking at the two suns of Tatooine. That’s a moment that’s completely understandable on its own terms. He’s just become a double orphan, but when the music comes in, it’s addressing much more universal issues. It’s talking about a young person at the point of destiny — where his life is going to take a big shift. The two suns add this other-worldly element to it. They remind you that you’re not in a desert on Earth. This is somewhere else. A galaxy far away.

HOW PICKLED SHOULD YOU BE?

HULLFISH: I’m going to play devil’s advocate with a question here. In “The Conversations” it was asked of you, “I know you usually read the original novels of the films you work on our based” — and that’s kind of that idea of steeping yourself in the story. I’ve heard other editors say they absolutely do NOT do it. They don’t read the source material. What’s the value and the danger with either of those stances?

MURCH: It can be dangerous. You can do too much research. But some level of research can be helpful.

MURCH: It can be dangerous. You can do too much research. But some level of research can be helpful.

I did read the novel “The English Patient,” but I read it a couple of months before I ever worked on the film — and before I ever read the screenplay. Before I ever knew that they were going to make this film and that I was being considered for the job of editor.

That kind of research lays down a layer of undercoat, so to speak, in painterly terms. I don’t fully remember everything in the novel, but I was aware of some of the decisions in an intuitive way: for instance, of why there were no scenes with Kip learning how to be a bomb-disposal expert — which are in the novel and not in the film.

So I feel the absence of those scenes, but it’s not something conscious and I didn’t refer to the novel while I was working on the film. I don’t even read the script when I’m editing the film. I’ve read the script of course and made notes about it, and even worked out a timing of it. But when I look at the dailies, I play a kind of mind-game pretend that it’s a documentary. “Oh, look, somebody left some material here overnight. I wonder if we can make a scene out of it.”

I hardly even look at the script supervisor’s notes. I have to have them in case there’s a problem, and I also will refer to the script if there’s something I really don’t get. “Why did they do this? Did they do this in the screenplay or is…” But in general, I relied on my vague impressionistic memory of both the script and the novel, but then interpreted through the very specific material that Anthony shot.

THE VALUE OF THE CHAINSAW CUT

HULLFISH: I’m really fascinated by process — including the process of getting a film from the editor’s cut to the end. You mentioned that on The Unbearable Lightness of Being you never took that film down in length. But you said that on The Godfather: “Frances cut it down to two hours and 20 minutes, but it was clear it didn’t work at that length. Then when we restored the length, somehow, having gone so deep, it didn’t come back exactly where we had before. We learned things by going that far.”

I’m really interested in that. Can you talk a little bit about what you learned on that specific thing, or what could it have taught you if you can’t remember the specifics?

MURCH: There’s occasionally a similar technique in production photography where the DP will “blink” the key light. For example: here’s a scene that has four sources of light, the key being the main source. Just as a check, the DP will ask the gaffer to turn the key light off to see more clearly what the other lights are really contributing.

So by removing something that seemed essential, you can see the residue of what’s left. Sometimes the DP will turn the key light off and decide, “Actually, it is better without the key.” So there’s the editorial equivalent of that, where we cut out the very scene that seemed to be most important just to learn what the other scenes around it are contributing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U_u7Hvj14s0

The example I give in “In The Blink of an Eye” is from Julia, where — after the preview — the audience seemed to be confused “Where is solid ground in this film?” Because the screenplay at the beginning was a flashback within a flashback within a flashback within a flashback. And so flying back to London, I thought, “Hmm… We could cut out the scene on Long Island in the 1950s and that would remove one vertebra of flashback chain.” I proposed the idea to Fred Zinnemann, and he thought we should try it.

He realized there was a problem with the chain of all these memories within memories within memories. And as I was removing the scene — we were working on a Steenbeck, and the tape splices were making little screaming noises as I undid them – Fred said, “You know when I read the screenplay, and I got to this scene, on page 7, this was the moment that told me I could make this film. This was my personal entry point into the story.”

I naturally hesitated because — “What are you telling me?”

HULLFISH: That sounds like a critical scene!

MURCH: And he waved his hand, “No, no, no, go ahead. Cut it out.” And he made the analogy that certain scenes are heart scenes and other scenes are like umbilical cords. Both are important. You have to have a heart. You have to have an umbilical cord. But we don’t walk around with the umbilical cord. We walk around with the scar of that amputation, which is our belly button.

This scene, for him, was an umbilical cord. It got him into the movie, but once his sensibility was in the film, then he realized that he no longer needed the scene.

PERSPECTIVE AND OBJECTIVITY

HULLFISH: You mentioned that in early screenings of The Conversation there were times when the audience was completely flummoxed. That’s interesting. Not to be harsh about it but that’s a failure of objectivity. You thought the film worked and then you showed it to a screening audience who didn’t.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EyexoSJ1tsg

MURCH: That happens to a certain degree on every film. It was particularly true on The Conversation because the odd thing about the film was that it’s a portrait of an “unheroic” character. This emotionally repressed person, Harry Caul, who does a very technical job – he doesn’t seem to be someone you would choose to be a conventional hero of a film. But that was what interested Francis about Harry. He would be, in any conventional film, a completely tangential character, and Francis wanted to try and make him a central character, to see what would happen.

The film was also a mixture of a detective thriller and a character study: Francis said he wanted to combine Hermann Hesse’s Steppenwolf and Hitchock’s The Wrong Man. And those two things don’t really alloy together naturally. That was, I think, what was confusing to the audience: “What is this? If it’s a thriller, then you don’t need all this character portrait about someone so boring.” On the other hand, people also felt, “Oh, this is a really interesting story about a type of character that has never had a film made about them before. You don’t need to hyper-inflate it with this murder mystery stuff.”

The trick on The Conversation was finding how to give just enough of the character study, and then just enough of the thriller so that they were in as much of a harmonious balance as we could get. It was a delicate balance and very difficult to get it right. Balancing a pencil on its point.

HULLFISH: Did something happen similarly with The English Patient where audiences were confused or where you realized that something needed to change?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z40Tipkm4IA

HOW A SCRIPT IS LIKE A BALLOON ANIMAL

MURCH: There was a scene in the book and the screenplay where Kip goes crazy because he hears the news of the bombing of Hiroshima. He holds everyone at gunpoint and has a rant about the white West and its subjugation of the rest of the largely coloured world. “You wouldn’t have dropped the atomic bomb on Europe. You dropped it on Japan.”

It was perfectly well written, perfectly well acted. There was nothing artistically wrong, but it didn’t fit in the film at that late point in the story, because we haven’t been thinking about Hiroshima. It seemed to come out of nowhere.

So we decided to cut it out. But then after that scene, Kip is a transformed person, so we can’t just cut it out, or we have to explain his transformation. So what are we going to do? We went around in circles for about a week. We have to have some scene that will trigger his transformation. Finally, my assistant, Edie Ichioka, said: “You know, Chief, a bomb is just a bomb.”

What she was saying was, “Yes, there’s the atomic bomb, but there’s also the booby-trap bomb that kills Hardy, the sergeant who was working with Kip — Kip’s assistant. And that could be enough to trigger the kind of his ‘sitting shiva,’ in a sense” — the Sikh version of that. Where he lets his hair down and he just goes quiet — won’t talk to anybody. And the booby trap death of Hardy is enough to trigger Kip’s transformation.

It’s a very good example of what I was talking about earlier with the balloon zoo animals transforming from a giraffe to an elephant. We took out a major scene in character development. It was actually a scene about which Michael Ondaatje, the author of the book, said: “Whatever you do, don’t cut that scene out,” because it meant a tremendous amount to him, but out it went.

Nonetheless, the script gave us the raw material to solve that particular problem in a different way. We were able to transform the giraffe into the elephant.

HULLFISH: I was thinking about a very different thing that you mentioned. On that film, if you’d had scene cards — and you probably didn’t have cards on that one….

MURCH: Yes, we did have scene cards

HULLFISH: That scene would have been one of those critical turned, diamond scenes, right? And I would think you can’t cut those diamond scenes out.

MURCH: But what that really just says is, at this point in the structure of the story, there HAS to be a diamond card, whatever it is, because things are coming to an end. And, thanks to Edie, it was a diamond that involved one of the characters that we came to know and love in the film. And because those two guys, Kip and Hardy worked as a team in life-threatening bomb disposal, they loved each other. He was killed by the very thing that he normally would be neutralising – a German bomb. So that all resonated nicely with the story.

LESSONS FROM TOUCH OF EVIL

HULLFISH: On Touch of Evil you said, “When I started working on the project, I never expected that we could do everything (editorially) that we wanted to do. In my experience, even if you have all the necessary resources, you’re lucky if seventy-five percent of the ideas pan out. A good rate of success for anybody’s notes about film.” What do you think that says about Orson Welles?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V-Oqn2hMp1M

MURCH: Pretty amazing. You can get a copy of that memo if you buy the Blu ray or the DVD of Touch of Evil — the package includes a copy of those 58 pages of notes. It’s a fascinating document because he’s writing to the very people at the studio who were his enemies, so he has to get his point across, but he has to be very diplomatic.

He was writing to Edward Muhl — the head of the studio who had betrayed him in a sense and recut the film that he wrote. There are all kinds of tortured politics around this. It was a very carefully and passionately written, but diplomatically very astute document.

The tragedy is that we never really got to see what Orson Welles would have made with Touch of Evil. This is not the director’s cut. This is us doing what he said in that memo. What then should have happened is we would show that version to Orson and he would say, either, “It’s great” or “OK, now that I see this, I want to change something else.” But because he died in 1985, we never got to do that.

HULLFISH: But you had to play that role for him, in deciding whether the note was going to stay or go.

MURCH: Right.

HULLFISH: Because otherwise, you’d just do all the notes.

MURCH: I think I was mainly talking about technically, can we do this? Because we had no access to the B-negative. It was destroyed. We had the negative of the final version of the film as released by Universal and we had a manufactured negative of the preview version of the film, which is probably what Welles saw that prompted these notes. It was discovered, I think in the library at UCLA sometime in the mid-70s almost 20 years after the film was made. So we made a negative out of that, and those were our resources. Along with the magnetic three-track sound mix: dialogue, music, sound effects.

HIS MUSES

HULLFISH: Michael asked you, in “The Conversations,” “I wonder if you similarly are influenced by the other arts.” And you said, “Yes, they are the spark points. They are points of the phenomena of life.” Talk to me about muses. What do you do to get yourself artistically motivated or involved in a film? Anything specific?

MURCH: Obviously, read the screenplay and talk to the director. I always write up — if not just for myself, also for the director, maybe eight pages of notes on the screenplay. I parenthesise all that by saying: these are just top-of-the-head ideas about where I was engaged or where I was a little confused when I read the screenplay

Pointing out that I didn’t quite understand something from the screenplay itself. Or at a certain point maybe the director could consider a certain idea to amplify what was on the page.

I just throw these things out — not necessarily for the director to take action on — but so that hopefully there might emerge a third idea that neither of us had thought of.

I also time the screenplay. So — like a script supervisor — I will take a day or two with a stopwatch and try to visualize the entire screenplay down to the second and make a database with those scene timings. I do it twice and get two sets of times that I can compare with each other.

I also time the screenplay. So — like a script supervisor — I will take a day or two with a stopwatch and try to visualize the entire screenplay down to the second and make a database with those scene timings. I do it twice and get two sets of times that I can compare with each other.

And then, when I get the timing from the script supervisor, I also put that into the database and see how they all correlate. If there are wildly different times for a scene, that will rise to the top of the list. And then I’ll ask the script supervisor for instance: “These three scenes: I thought they’d be 40 seconds, but you say they’re two minutes. What’s going on?”

Either they’ll say it was a mistake. Or they’ll say, “The director wants to linger very long on all of this. It’s not obvious from the screenplay.” But the effort of spending a day or two with a stopwatch, speaking the dialog and pacing out the steps and putting the knives and forks down and, you know, shooting the guns and imagining the battles is another way of entering into the spirit of the film on a deeper level than just reading the words.

A LIFETIME OF NLEs

HULLFISH: You said you, “enjoy variety. I thrive on it, actually.” And one of the things that I thought about when I read that was your NLE of choice.

MURCH: Right.

HULLFISH: So after cutting on film, you went to what?

MURCH: Avid on The English Patient, in 1995.

HULLFISH: With Cold Mountain in 2002 comes the switch to Final Cut? And since then, to Premiere?

MURCH: After Hemingway & Gellhorn, I jumped back and forth from Avid to Final Cut 7 for five years or so. On Tomorrowland with Brad Bird I used Avid. Then on Coup 53 I switched to Premiere in 2015.

HULLFISH: What was the motivating choice to switch from Avid to Premiere?

MURCH: Each NLE is like speaking a slightly different language, and I’m curious about languages.

HULLFISH: That’s exactly how I describe it.

MURCH: It makes you look at the material in a slightly different way. And I know there are wonderful editors who are absolutely not interested in changing their NLE at all. They’re very comfortable with their Steinways, so to speak, and they would never play on a Yamaha.

I had used Avid when I was a third editor on Joe Johnson’s Wolfman in 2010. And the last time I used an Avid before that was on K-19 — Kathryn Bigelow’s film in 2002. I was amazed at how little it had changed. And then even on Tomorrowland, in 2015, it still hadn’t really changed. So I was interested in something else.

The nickname, in those days, for Premiere was Final Cut Eight — meaning….

HULLFISH: What it would have been.

MURCH: It might have been this. Not completely true, but a lot of the people who were working at Apple migrated to Adobe at that time, in 2011, when Final Cut 7 was abandoned.

It was a good experience working with Premiere. I got to know the developers well, and they’re very aggressive about supporting editors. Much more so, in my experience, than Avid.

And with Final Cut during the years from Cold Mountain on, I would get together with Apple at the end of each film and download my thoughts: But that would be every two years or so. Whereas Premiere’s constantly putting out new versions every six months or so. Sometimes more frequently.

And with Final Cut during the years from Cold Mountain on, I would get together with Apple at the end of each film and download my thoughts: But that would be every two years or so. Whereas Premiere’s constantly putting out new versions every six months or so. Sometimes more frequently.

HOW TO CUT LIKE WALTER MURCH

HULLFISH: You said, there are three things to consider in an edit — “What shot shall I use? Where shall I begin it and where shall I end? Rhythmically, the last one is the most important. You end at the exact moment in which it is revealed everything that’s going to reveal in its fullness without being overripe.”

I love that. I just wanted to say those words. Can you expound on that?

MURCH: Yes, the choice of the last frame of a shot is perhaps the most important part of the “performance” of the editor. It is roughly the equivalent of the bowing technique of a violinist, or the fingering technique of a guitarist.

My unbreakable rule in this regard is never to find that frame by “scrubbing”, but to choose it in real time.

HULLFISH: And you still do that? You don’t scrub?

MURCH: If I’m going to use a particular shot, I’ll find a good point to start it and then I’ll run it and then, at a certain point, the “rightness quotient” builds to maximum and I hit the stop button. After that, the shot runs out of gas, so to speak.

I’ve been doing some version of this since The Conversation — even though I was editing that on a KEM. I was using the frame counter as an indicator of which frame I stopped on. Then I will rewind and run it again and try to hit the same frame again. If I hit the same frame twice in a row, that tells me that’s probably a good cut point, because it’s impossible to do that, to hit that same frame, in any other way than musically. To sensitise yourself to the visual music of the shot and respond accordingly.

24 frames are going by a second. It’s like being at an amusement park shooting gallery: the ducks going by at twenty-four ducks per second. How can you shoot THAT duck? You can’t do it. It’s just too fast. But if you can internalize the rhythm of the shot, the dialog, the camera work and (makes “clunk” sound) make the cut at that point. And if you can do that twice in a row, that means you’re onto something.

In the end, you might change the out point because of other factors relating to the film as a whole — but for the moment — when you’re assembling things – that feels good. If you choose a cut point and it doesn’t feel good, look at the timecode and you’ll see: “That was three frames earlier than the other time.”

What that tells you: For this film, for this shot, that’s what three frames feels like. You’re trying to pick up the rhythmic signature of this particular film. And that’s a very good way to learn how to do it. The danger of scrubbing back and forth to find a frame is that it cumulatively produces kind of tone-deafness to the rhythms of the film.

HULLFISH: Thank you, Walter. We’ll continue the rest of this discussion in another Art of the Cut interview coming in the following weeks. I’ve got some questions for you about things you said in your books, “In the Blink of an Eye” and “The Conversations” with Michael Ondaatje.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now