Maryann Brandon, ACE is a Primetime Emmy nominee for Alias, ACE EDDIE nominated for Star Trek, How to Train Your Dragon, and for Star Wars Episode 7, for which she was also nominated for an Academy Award.

Her filmography also includes Venom, J.J. Abrams’ Super 8, Dreamworks’ Kung Fu Panda, and Mission Impossible 3.

Maryann and I have talked twice before on the text version of Art of the Cut on Provideocoalition.com for Star Wars: The Force Awakens and for Passengers.

In this interview, we discuss her work on Star Wars: Rise of Skywalker.

This interview is also available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about how long you’ve been working with J.J. Has it been before Alias or was that the beginning of your relationship?

BRANDON: That was the beginning. That’s when I met him. Yeah, it’s been a while. When was Alias? 2000? I keep wanting to say 2001 or 2003.

HULLFISH: 2001. That’s a long relationship. Do you remember how that began? How he found you or you found him?

BRANDON: I was doing small features — lower budget features. It was just getting harder to travel because a lot of them were on location. And I had a kid in third grade and a kid going into kindergarten. We traveled a bunch with them — which was great and we had a fantastic time — but, a friend of mine, who had tried to hire me on Felicity called me. I was a little reluctant to do television. But she said, “You’re gonna love J.J. Abrams and Matt Reeves.” Long story short, she introduced me. She convinced me to meet him on Alias because they were cutting at Disney, which was very near to my house. So it sounded like a good, good thing.

When I met him, we instantly hit it off. I spent most the interview laughing and he spent most of it telling funny stories. And then he said, “I’ll see you tomorrow.”

HULLFISH: I love the idea that you were concerned about family and how much time you were spending and traveling and how close the place was to your home. We need to be conscious of our own well-being when we’re deciding on what to work on.

BRANDON: Of course. I mean, that’s everything. Every decision I made has been really with that consideration first and foremost. I’ve talked to other people in the editing world, and I think they do that as well. I think it’s becoming harder to deny that you’ve got to make a balance or it’s not going to work.

HULLFISH: You’ve cut with several other directors — many other directors. We know what the benefits of that are. Are there any drawbacks to working with someone as long as you have with J.J., or is it just good things?

BRANDON: I haven’t found any drawbacks. J.J. also does a lot of other things — he produces plays; he does television. It’s not just feature films. I think that keeps it fresh and real. And I learn a lot when I go out and work with other directors. I absorb things and I bring what I know and I bring my strengths and weaknesses and I bring them back. So every time I do another project with J.J., I have this other experience that I come back with. I usually come back stronger and from a more confident place — a been-there-done-that place. And he does as well.

We bring our mutual experiences to it, and that’s a huge strength. Combined with the fact that we’re so familiar with each other. A lot of times we’ll finish each other’s sentences and just look at each other and say, “Yeah, I know exactly what we’re going to do here.” And so that’s the benefit. No. No drawbacks for me.

HULLFISH: That’s awesome. I’m sure it helps, like you said, to be working with a lot of other directors that you’re pulling creatively from those relationships.

BRANDON: I think you have to. Otherwise. it would get really tiring. Because then I would only understand J.J.’s style. That would make it very difficult.

HULLFISH: We talked about cutting TV in 2001. Back then the difference between TV and film was quite a chasm, but the landscape’s changed quite a bit recently. What differences did you notice between the two in the early years when you jumped over to Alias? Have you done any TV since then?

BRANDON: I haven’t done any TV since then. Yes, it has changed. And I have always said the best training I ever got was an Alias because it was like making a mini-feature every six weeks. It was intense. It was a lot of footage. It was figuring out things on-the-fly and figuring out how to rearrange things so they made more sense. We’re doing the final re-write in the cutting room.

Everything was on a much shorter schedule because you were making 16, 17 episodes a season. The turnaround — because an episode took 10 days to shoot — but there are only seven days a week. So you can imagine: we were losing time every week in terms of getting ahead of ourselves. And so in those days, there weren’t eight-episode seasons or six-episode seasons that you had six months to do. Network television needed to be fed more product. The schedules were insane. It was ridiculous.

HULLFISH: You also made the jump from cutting film to cutting digitally. Do you remember what project that happened on? Or what year that happened in? Have you always been on Avid or have you used others?

BRANDON: No. I remember it very distinctly. I cut a film from Matthew Robbins called Bingo (1991) But I think I did a digital NLE earlier than that — on a film called All’s Fair (1989). And the director said to me, “There’s this company called Ediflex and they want you to try their system. Can we try it on this film?” And it was really cumbersome. You had a stack of tape decks and the tape decks would rearrange to each cut and you’d hear them click in when they were trying to do a cut. And it was slightly manual, slightly digital. It was fully digital, but the screen was hard to read. It was half of me trying to figure out the system while I was desperately trying to figure out the film.

BRANDON: No. I remember it very distinctly. I cut a film from Matthew Robbins called Bingo (1991) But I think I did a digital NLE earlier than that — on a film called All’s Fair (1989). And the director said to me, “There’s this company called Ediflex and they want you to try their system. Can we try it on this film?” And it was really cumbersome. You had a stack of tape decks and the tape decks would rearrange to each cut and you’d hear them click in when they were trying to do a cut. And it was slightly manual, slightly digital. It was fully digital, but the screen was hard to read. It was half of me trying to figure out the system while I was desperately trying to figure out the film.

Thankfully, there wasn’t tons of footage, but that system did not work for me, nor did that system last long. After that I went to LightWorks. I think I did Bingo on the LightWorks. I did LightWorks for a few films. They tried to copy the way a KEM works. So things go left to right and the switches and the buttons looked like a KEM, and it was also very button-heavy.

Then I switched to Avid on Grumpier Old Men (1995). There were three editors on that film, because it was a very short schedule. They just sat me down in front of an Avid and I kind of self-taught myself. I’ve been on Avid ever since.

There was one point on Alias that J.J. wanted to try Final Cut Pro but there was so much footage, so much story to tell. I needed to not worry about the system I was on.

The good news about coming up cutting film was that I still use an Avid the way I cut film on a Moviola. I feed in the choices and I come out with a cut on the right-hand side. So I don’t use a lot of fancy bells and whistles of the Avid that I know a lot of people do use.

HULLFISH: What skills do you think you brought with you because you cut on film?

BRANDON: I still look for the piece of the take I want to use. I still drop it in the way I would build a cut if I were building a film reel. I still put the sound to it the way I would line up sound. Slowly but surely, I’m learning some After Effects and how to do visuals. I know my way around visual effects now because it’s necessary, but my main thing is performance and story and I still build a cut that way.

BRANDON: I still look for the piece of the take I want to use. I still drop it in the way I would build a cut if I were building a film reel. I still put the sound to it the way I would line up sound. Slowly but surely, I’m learning some After Effects and how to do visuals. I know my way around visual effects now because it’s necessary, but my main thing is performance and story and I still build a cut that way.

HULLFISH: With Star Wars, once production was done and you’d assembled the first cut, what kind of structural discussions or decisions were made and how did that process play out?

BRANDON: Well, we’d sit down and we’d all watch it — my co-editor, Stefan Grube and I and J.J. and the writer Chris Terrio, and the producer Michelle (Rejwan) and Kathleen (Kennedy) Everyone would throw in their version of what their impression was and what story we’re telling, and we looked for the clearest, best story performance and came up with where we were going and what the balance would be.

It’s an evolving process, like any film. Once it’s up in front of you, you can see the strengths and weaknesses and what’s working and what’s not working, and we just tried to balance it. There’s nothing very specific to talk about because like all films, you take one thing out of one place and it works better out of the film or in another place, and you try a bunch of stuff that intellectually you think will work and throw it up there again and see if it does work.

HULLFISH: Did you use sene cards on a wall to help do that structural stuff? Or no?

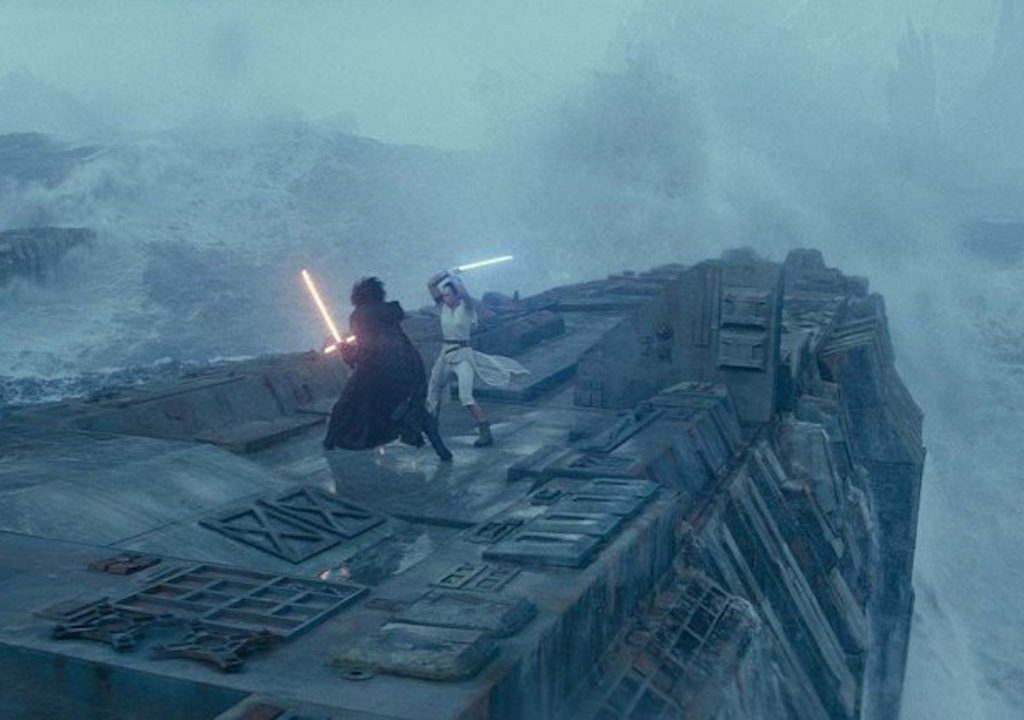

BRANDON: I have done that in the past. They’re great to just remember what scenes are what. I don’t find myself using them that much because I didn’t sort of grew up in the business with them. We did use some scene cards on this film for the battle at the end because we were trying to figure out where to intercut going back to Rey fighting the Emperor or going back to the battle up above. So we used scene cards to sort of break that down and switch it around, but pretty much, once we did that initially, we abandoned it.

BRANDON: I have done that in the past. They’re great to just remember what scenes are what. I don’t find myself using them that much because I didn’t sort of grew up in the business with them. We did use some scene cards on this film for the battle at the end because we were trying to figure out where to intercut going back to Rey fighting the Emperor or going back to the battle up above. So we used scene cards to sort of break that down and switch it around, but pretty much, once we did that initially, we abandoned it.

But it does definitely give you a visual if you have a big bulk of scenes like that, and oftentimes when they’re shooting a scene like that, especially with a lot of visual effects, the numbering system isn’t really going to help you, so scene 235 doesn’t necessarily come after scene, 201.

It’s great to have the script and the script supervisor’s notes, but they’re not helpful. The scene cards are more helpful for that.

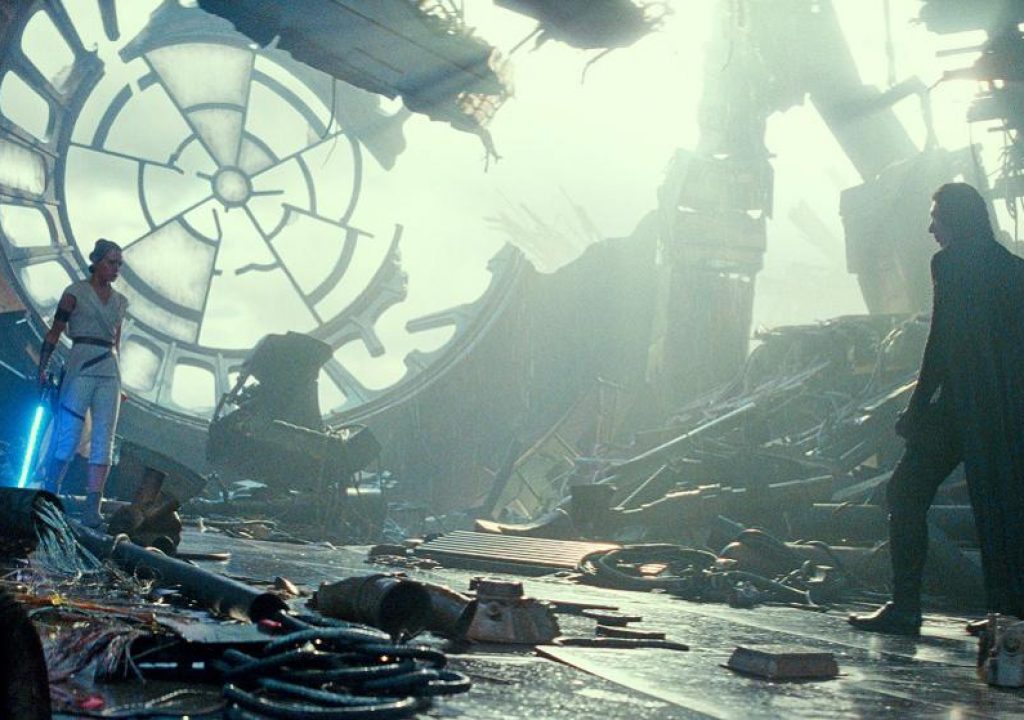

HULLFISH: During that intercutting — when Rey was off on her own story and the rest of the cast was off doing something else — do you remember what motivated some of those exact moments of intercutting? Or how did the intercutting between those stories play out?

BRANDON: We tried to find places that we’d leave in an emotional moment where the team up top was in trouble. We tried to match the emotion going down below. You didn’t want to be happy for one part of the team knowing the other part of the team was in trouble. We were trying to balance emotions and keep things going that way, so we just tried to pick dramatic moments that we knew you could leave and when we’d come back you could pick up that feeling straight away.

It’s tricky. It IS tricky. There’s an argument to be made for leaving a scene at several different points, and we wanted to find the best balance. I think we did, in the end. I think the end battle — to me — works first and foremost on an emotional level, which I’m most happy about because the details to me sometimes aren’t as important as the emotion and the drama and feeling your characters.

It’s tricky. It IS tricky. There’s an argument to be made for leaving a scene at several different points, and we wanted to find the best balance. I think we did, in the end. I think the end battle — to me — works first and foremost on an emotional level, which I’m most happy about because the details to me sometimes aren’t as important as the emotion and the drama and feeling your characters.

HULLFISH: Were those emotional moments when you were cutting back and forth not exactly the way the script was? Was it because you had a better sense of the emotion from watching the dailies?

BRANDON: In a big battle scene like that, the script — at best — is just a guide. I’ve worked on several films — like Venom had a big battle scene at the end. And although the scripts are very useful for shooting, obviously, you often go away from the script because it’s really just a guide and then you get what you get. And of course, you’re adding visual effects later, so you can have other things happen. You can take the footage and bend it a little bit to having other things happen, especially in scenes like that. You kind of find the story as you’re going along and feeling what’s right and where you want to be next.

So it’s very hard to script a battle scene. If you’ve read any scripts with big battles in them, a lot of times it’s four or five lines that say, “The rebellion shows up in their x-wings and fight the tie fighters.”

That’s just a description. Then you’ve got to figure out the shots. Then you’ve got to figure out the people and what they’re doing and how they’re reacting. And that’s not often scripted.

HULLFISH: It’s an eighth of a page of description for six minutes of time or ten or twelve or fifteen minutes of time.

HULLFISH: It’s an eighth of a page of description for six minutes of time or ten or twelve or fifteen minutes of time.

BRANDON: Exactly. I mean, when it says the rebels are losing, that can be 10 shots of your characters taking a hit. It’s impossible to write those out.

HULLFISH: Scene transitions seemed really important to me — as they always are — but in this movie, the transition from one scene to another seemed really critical. As you came out of cutting dailies, how did you start to massage those transitions from one scene to another?

BRANDON: Well, Star Wars always has wipes, so there’s always that. When you’re done, you can just wipe into another thing, and that works quite often very well.

HULLFISH: You were talking about the intercutting that you need to transition on an emotional moment or you cut a scene one way and it ends on a wide shot but then you realize that you started the next scene — because they’re shot out of order — and the next scene starts with a wide shot. Now you’re trying to massage that transition because you know how one ends and the next one begins.

BRANDON: I’m very aware of transitions and I’m very aware when I think a scene has overstayed its welcome or under-stayed its welcome and needs a little bit more, and I usually try to find something — sometimes it’s really just a visceral thing where a spark can go off and then you follow the spark to a person walking into a room. Sometimes it’s an overlap of a line that brings you into the other scene. A lot of times you’ll hear, the screech of the Falcon before you see the Falcon, for instance.

Each one is different. I don’t take anything for granted. A lot of times J.J designs them and has a shot he wants to come in on a scene on, and I’ll figure out the “out” to get to that. If it works great and if it doesn’t work, we figure something else out.

Each one is different. I don’t take anything for granted. A lot of times J.J designs them and has a shot he wants to come in on a scene on, and I’ll figure out the “out” to get to that. If it works great and if it doesn’t work, we figure something else out.

Sometimes it’s a musical thing. Sometimes John Williams comes in and has some brilliant musical thing or we’ll have some temp music that’ll bring us out of a scene or into another scene.

I don’t have one answer. I have a lot of answers.

HULLFISH: I would figure that you’d have a lot of answers. It’s a pretty complicated question. That’s interesting about John Williams. Did you guys ever kind of give him some latitude? Like, “If you need an extra couple of seconds to finish a musical phrase or ring something out, let me know.”.

BRANDON: I always said to John Williams, “If you need anything, tell me what you’re feeling.” Because if the music doesn’t work or the composer — and I’ve had this with Michael Giacchino as well (Star Trek composer) — if the music isn’t working, then there’s something wrong with the cut, and we need to figure out what it is.

So I often — and always — when I work with composers, I feel like our jobs are so intertwined. That’s a given that they have latitude.

HULLFISH: Because this is such an iconic series of films and it’s got such a deep history, what kind of sound and music did your assistants pre-load for you from the previous movies?

BRANDON: Every single movie that John Williams did. All John Williams music and then we pretty much pulled from all the Star Wars films. We had eight other films to pull music from. That was a gift, right?

And Skywalker provided every piece of Star Wars sound there is. So we pretty much had a library of Star Wars. We also carried with us a music editor from day one amd a sound editor from day one. So if I finished a sequence, I’d put some general sound effects in — specific sound effects that I wanted, and then I’d give it to Robbie Stambler or my assistant, Jane Tones and one of them would fill out a lot of the sound. I would sort of say what I wanted and then they’d embellish it.

We had a pretty great team.

HULLFISH: Did you find that there was a conversation going on — in the NLE, not human-speaking conversation — between hearing the scene with the new sound effects and looking at it thinking, “With those sound effects It changes things.”

BRANDON: I use sound as part of the cutting, so if I really wanted to affect something or the sound was a major part of the scene, I always asked for the piece of sound and put it in. Same thing with visual effects. Marty Kloner, my visual effects editor, and Kerry Blackman putting in laser swords and blasts and sometimes doing split screens for me. They were amazing. If I wanted to extend a shot when an actor was speaking, I could even have them close their mouths. They are pretty great at what they do. Anything I needed: there was a team to do it before it even went to ILM.

HULLFISH: When did you come on to the movie? Did you cut previs before shooting started?

HULLFISH: When did you come on to the movie? Did you cut previs before shooting started?

BRANDON: We didn’t really have previs on this film. We did use previs as we went and a lot of postvis, but we didn’t deal with a lot of previs. I came on two days before we were shooting. I usually come on a week or two early but I was doing Venom up until that Saturday. I flew on a Sunday to the UK and I started on a Monday and they started shooting on a Wednesday. So that was really tight.

HULLFISH: It’s no wonder you need a break!

BRANDON: Exactly!

HULLFISH: So with no previs — with something like the big action battle at the end — did you use previous parts of the other Star Wars movies?

BRANDON: Sometimes, yeah. Sometimes we’d pull out shots from other Star Wars movies and just put them in as a sort of marker. Sometimes we’d use stuff we’d pull off the internet just to kind of fill in some battle stuff or transitions. We’d use anything we could find to help us.

HULLFISH: Pulling stuff off the internet!

BRANDON: Like space stuff to put in a background or something, just for the time being so we could screen it and it wouldn’t be green. As long as you kind of know what you’re looking for, it’s not hard to find.

HULLFISH: George Lucas famously used World War II dogfight footage for that original Star Wars movie.

BRANDON: Exactly. I mean, it makes total sense to me, right? It’s easier to have a base for something and then see what you need as opposed to just a blank page, right?

HULLFISH: Absolutely. I’m really interested to hear that there was so little or no previs. That seems unusual on a big movie these days.

BRANDON: You know what? We didn’t have time. Our schedule was pretty short. J.j. was brought on much later than he should have been. They had three months less time to write the script, so it was tight.

HULLFISH: Do you cut action scenes on mute to start or are you building them with the sound as you go?

BRANDON: I pretty much do it on mute and then add the sound. I mean, I got to start somewhere. If I was worried about the sound the whole time — carrying the sound — it would prohibit me from concentrating on what the picture needs to be, so I do mute and then add the sound and then sometimes I’ll try and find music before I even find sound. But it’s always picture first.

HULLFISH: That reminds me of a gift that I gave to my editing team on one of my last movies, which was the Ten Commandments of Film Editing, and one of them was “Temp not with John Williams. He composes not for thee.” But, for you, he was really composing.

BRANDON: For us he was perfect.

HULLFISH: I bet he was. You mentioned working with Stefan on the film as a coeditor. He had worked with J.J. on 10 Cloverfield Lane. Is that how he came in?

BRANDON: He did. He worked on Cloverfield Lane. And he also cut the trailer for Star Trek into Darkness. They worked together in marketing as well. And I think he has a couple of projects lined up, at Bad Robot. He’s really smart and talented and it was really fun to work with him.

HULLFISH: How did you two collaborate?

BRANDON: We collaborated differently than Mary Jo and I used to collaborate, which I brought to the table. I talked to him upfront: “This is gonna be a really short schedule and I don’t want to divide up the film. I just want to cut the film, so, I’ll take whatever. If I’m working on something, you take the next thing to come in. The important thing is that by the time they finish shooting, we have some assembly.” And we kept going from there.

So basically each of us had a go at everything. We just worked off of each other. We talked a lot. We really collaborated on this film.

HULLFISH: Did you guys do any screenings beyond studio or friends-and-family screenings and how did they affect what you were doing?

BRANDON: We did not. That’s the hardest thing about working on a film like Star Wars. You really can’t because if it gets out, it’s not a good thing. We really only could screen for the studio and limited friends-and-family. We did not have a lot of screenings, so we were working with a very small reaction to the film. People like Spielberg watched it because he’s always been a part of it and people at Bad Robot, but really we couldn’t go outside of that.

HULLFISH: Does that affect you in any way? Or do you just have to be confident in your own objectivity?

BRANDON: I think you’ve got to take what they say and figure out how it would affect a wider audience. I know people really put a lot of stock in previews and there is a lot to be gained from that. With these big action films, when they’re not sussed out and you’re still having ILM working on a thousand shots, they’re hard to preview anyway because people are taken out of the film (by the temp VFX.)

They say it doesn’t affect them, but it does affect what they think. They’re not the easiest films to preview. So I’m not sure even if we could have, we would have gotten an accurate response. Yeah, maybe if we had shown it to a more objective audience, we would have gotten more feedback. But I think we understood what we had and what we were going to release by the end of the film.

I think we had enough feedback and enough people had seen it. By the time a film is at that stage, it’s kind of what it is unless you’re going to plan on doing a bunch of reshoots, right?

HULLFISH: Did you guys do any reshoots? Was there anything you felt like you needed when you were editing?

BRANDON: We did. We added a couple of scenes. We had two weeks back in London in July and we added a couple of scenes and added some dialogue that we felt we needed. There were a couple of very small emotional moments J.J. and I and Stefan decided would benefit the film and we went back and got those.

HULLFISH: Can you tell me what those were? Can you give me an example?

BRANDON: The scene on the island with Luke, when Luke sees Rey. The film kind of informed us after it was together what it needed to say, so we went back and got that dialogue.

BRANDON: The scene on the island with Luke, when Luke sees Rey. The film kind of informed us after it was together what it needed to say, so we went back and got that dialogue.

There was a funny moment between Po and Rey when he lands the Falcon and it’s on fire. We wanted to have a more humorous exchange between them. A couple of things like that. Nothing major.

HULLFISH: I think it’s really interesting that you discover things — like those little light moments — where you’re watching a larger sequence of scenes and realizing that you need a little lift or something. Is that how it works?

BRANDON: I think that’s how it works. Sometimes there are plot things that might be confusing, and a little bit of a tweak or a new scene can help it. Sometimes the film speaks to you. You just want a moment.

One of the things on the reshoots we did: we shot Rey’s introduction, where she’s floating up in the air and the rocks are spinning around her because we just we wanted to introduce Leia and her and we had to go back and find good shots of Leia that we hadn’t used in (the previous film). We had those and it made us think, Oh, we can have this really fun scene to introduce Leia and Rey.

So the film kind of informs you of things it needs. And yes, levity is always good.

HULLFISH: I’ve talked to several directors and producers of movies I’ve worked on that they need to leave some room in the budget for reshoots and additions because you never know what you need until you get into editing.

HULLFISH: I’ve talked to several directors and producers of movies I’ve worked on that they need to leave some room in the budget for reshoots and additions because you never know what you need until you get into editing.

BRANDON: Exactly. Exactly. I think all films now build in reshoots because of the value of them. It’s like when you do animation films it happens all the time because you’re just creating shots, right? And you get to create more shots once you put your film together. It’s the same thing.

You’ve got a story and it can be told a little better. So why not? It’s a great investment.

HULLFISH: What amazes me is that you’ve got somebody with J.J.’s talent as a writer and a franchise with the resources to have the best scriptwriters, but that with scripts in general, you can’t sense the same things in the script that you sense in editing.

BRANDON: I think it’s hard. I don’t think you can. I think that’s why editing is definitely the final rewrite. You can’t avoid it. I don’t think you just put a film together and it’s exactly what the script was. I don’t think it ever is that because the written word is different than the visual. Or a performance can interpret something.

You can tell a joke 50 different ways — more. How do you tell that joke? Everyone is having an interpretation of that.

HULLFISH: It’s all those things added up together, and you don’t know what they’re going to turn into until you look at the dailies.

BRANDON: Correct.

HULLFISH: And even beyond the dailies, even if you see it in the dailies, a scene looks great but then you put it in the greater context of the entire story and you realize that the entire scene’s gotta go.

Were there any scenes that you needed to cut?

BRANDON: I think we cut some scenes.

HULLFISH: What was the running time of your editor’s cut?

BRANDON: It was over three hours. We were never going to make a three-hour film. It was just not going to happen.

BRANDON: It was over three hours. We were never going to make a three-hour film. It was just not going to happen.

The film will dictate how long it’s going to be. And I don’t think J.J. went into it saying it’s going to be any specific length. He would never do that. We all agreed that the story will dictate what it can sustain. Because it’s so easy in these really massively long films. They could be great, but if you fall out of the film as an audience because things are taking too long or the audience is ahead of the film and they know what’s going to happen — not in a good way — it’s not creating tension, it’s kind of creating boredom. Or you have too much time to spend looking at other things besides being enthralled in the story, that’s a problem.

HULLFISH: Where did the time come out? Was it just cutting down some of the big action scenes?

BRANDON: Cutting it down and rejiggering to make things feel like they were the right amount of time spent and that you got it and you moved on — or you felt it and you moved on.

I would never stay in a scene beyond where you lost the feeling. That’s terrible for me. So, I can’t point you to one place. It’s just a pacing thing throughout the film. Some films work with a slower pace. Some films work at a higher pace. This film — I believe — is very highly-paced where it needs to be, and not where it needs to be slowed down. It’s just a feeling.

HULLFISH: Thank you so much for all your generous time and congratulations on a great movie.

BRANDON: Well, thank you. And thank you for taking the time to interview me. It was lovely to talk to you. Bye, Steve.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or Instagram at @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now