Today I’m talking with Michelle Tesoro, ACE about editing The Queen’s Gambit.

She edited The SXSW Grand Jury Prize-winning feature film Natural Selection, which earned her the 2011 SXSW Award for Best Editing. She also edited the feature film On the Basis of Sex among others.

Her editing of TV series includes Netflix’s Emmy-nominated series When They See Us as well as episodes of Fringe, House of Cards, and Godless among others.

This interview is available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

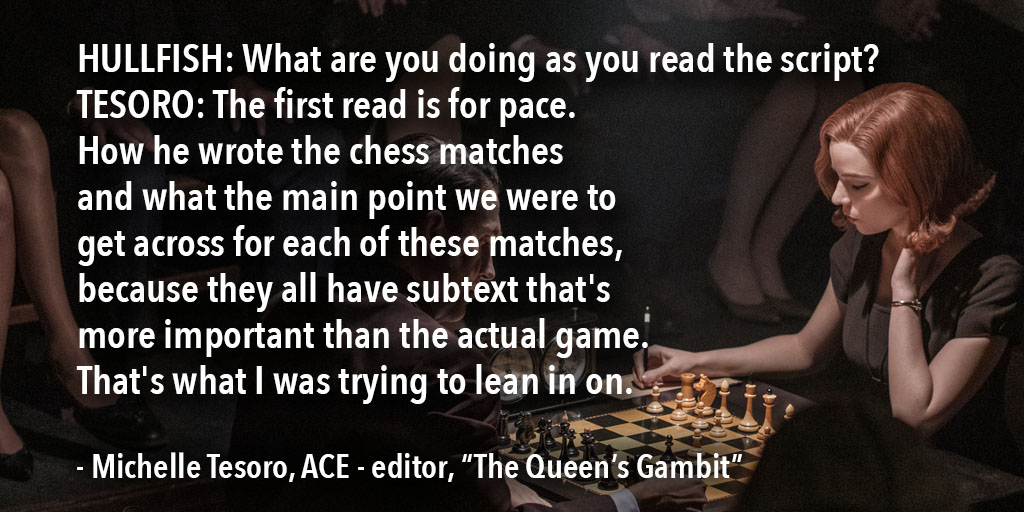

HULLFISH: Tell me about reading the script and how those scriptreading skills are important to an editor. Do you almost start editing the show when you’re reading the script?

TESORO: I do. I try to feel the pace. I think Scott was giving us — us meaning me; the DP, Steven Meizler; Carlos Rafael Rivera, the composer; and sound designer, Wylie Stateman — three episodes at a time in his beginning drafts.

A lot of it is for function — just to see if there is anything that I can spot that might not work or I should flag or ask him about ahead of time. I just try to imagine it in my head. How does that go? He’s written in a oner. He’s written in a transition. Here it seems like he’s leaving the transitions open to me or here’s one line that has a couple of pops of chess playing. That means I’m going to have to put that together whatever that’s going to be.

But I mostly think the first read on this for me was pace and how he wrote the chess matches and what the main point is we were to get across for each of these matches, because they all have some subtext that’s more important than the actual game. That’s what I was trying to lean in on and then ask him about — what he’s planning on doing and he would tell me, “I’m thinking maybe this match I’m not going to show anything. I may just shoot their faces and that’s where I think the story is, so what do you think about that?”

It was a lot of thinking ahead about it — talking with Scott about it and then after it was shot he would either come back to me and say, “It didn’t turn out the way I wanted it to. Fix it.” Or: “I think this is what the intention is, so you do what you do.”

HULLFISH: And the writer was the director, correct? Does that change things? Have you worked with other writer-directors and is your relationship with a director different because they also wrote the material?

TESORO: To me it’s really much easier because they’ve already imagined it in their head when they’re writing. The intentions are very clear. It’s one and the same. They’re not fighting with something, if they don’t agree with the vision. It’s not this different take on it.

When the director is not the write, I think it just depends on the influence the director has on the writer, on the script, to mold their vision with the script and just make sure that the intentions are one and the same for for all parties involved. But it’s nice when it’s writer-director because they know what you’re going to deal with.

Scott and I — this is our third project together. I think he knows what he can give me and he knows how it’s going to come together, so it’s easier when he’s writing — he’s sort of already imagining those transitions and things like that.

There are a lot of flashbacks — a whole flashback storyline in this series — which wasn’t in the book. So this was something that was new that he was filling in, in terms of giving a backstory to the character.

He said in the beginning, “I’m going to place these in the script and they may live there or they may not.” We had experienced this on Godless — where he wrote some back story flashback stuff and some of it we pulled out completely because it wasn’t working and then some of it we moved around — so he kind of knew that we could do that.

So when he shot these flashback sequences he shot extra things that maybe we could use as flavor. He’d say, “This is this scene number, but put it somewhere else if you want. This is maybe something we can play with.”

HULLFISH: Is there an advantage to working with someone multiple times so that when you’re reading a script and giving notes that person trusts your sense of story and you feel like you can speak in to the script this time?

TESORO: Yes absolutely. There’s a sense of trust. You know their writing. You know their sensibilities — going both ways it’s easier to be able to feel free to to speak your mind — especially if they keep reiterating, “Please tell me what you think.”.

HULLFISH: My issue sometimes with writer-directors is that sometimes — not always — is that they wrote it and the words are very important to them and you can’t talk them out of something that you might be able to talk them out of if somebody else wrote the words.

TESORO: This is true. Scott is pretty good knowing if something isn’t working. He’s always open to hearing why it didn’t work for you. Then it’s a discussion and if he’s right, it’s because we’ve discussed it we’ve talked about why a line is there.

But I have been in those situations where it’s my first pass had to include all of the lines. You can’t just arbitrarily lift things without a conversation, or at least trying what they wrote.

HULLFISH: I’ve had that discussion with multiple editors about the ability in an editor’s cut to make a change in the script and there are two schools of thought: “Never do it because the editor’s cut is for that specific purpose;” and a second school that says, No. “You make the cut be what you think it should be.”

But that can cause problems. What has been your experience in trying to tweak the editor’s cut to being something other than what the script is.

TESORO: This is a really good topic to discuss because I found that it changes depending upon what the director’s expectations are of that first assembly. And what form they’re looking at that first assembly.

It is good in terms of having it for record: here is this scene as it was written. Whether or not that ends up in an actual cut depends on the director because I’ve had the experience of: “I’m going to to exactly what was shot in the script. I’m going to give you everything even though I feel like this scene should be half the length it should be. But I’m going to give this my best shot because I don’t want to overstep that boundary if we haven’t haven’t talked about it already or I haven’t been given the explicit right to do that.”

I’ve done that and then they’ve been really disappointed saying, “Well, you just gave me the script!” What this what this comes to is really the communication between an editor and a director to be clear what the expectation is. What would you like me to do?

And if it’s something that hasn’t been told to you as the editor — if you have this idea — being able to have that conversation and say, “I cut this the way that it is, but I feel maybe you could lose this line or maybe we could approach it this way” and then have that alt cut if you feel strongly.

I’ve been doing these versions of cuts where I just start showing them if they’re open to it. If I can give it to them by the end of the week — maybe at the end of every week — I give them a few sequences that have come together just so they can see how it’s coming together out of context.

It’s a great way to kind of head those things off at the pass as well as buy you some time on the back end when you’re trying to put it all together.

HULLFISH: Yeah. I talked to William Goldenberg about cutting News of the World and it was his second film with Paul Greengrass. Paul said, “I don’t want you to cut this the way the script is” so that’s a great thing to have a conversation with your director ahead of time if you can.

Talk to me about those flashbacks, and your approach to them and how they were used in storytelling and when they didn’t work and when they did work and how you felt you could get in and out of them.

TESORO: I’m a big fan of just cutting them in and cutting them out and it’ll work if the emotion matches on both sides of the cut. So I knew that the story was going to work without them completely. You could literally take these flashbacks out and you’d just be humming along.

But there were times where we needed information to understand who Beth was as a little girl — where she was coming from.

There are a lot of times in the show where Beth is by herself. She’s always alone. It seems like she’s better alone because she can control her environment. We sort of tried to use these moments as in and out points. When do we kind of want to see the internal? And what do we have of either the flashbacks with her mother; flashbacks of her father — which was a little bit more expositional — how can we inform what we’re trying to portray emotionally in the present with something emotional that happened to her in the past?

There are a lot of these flashbacks that weren’t necessarily in the script but ended up being shot. For example, very, very little Beth was looking through her mother’s books of math or when they’re crocheting or the needle point. Those little moments we put in places where she’s in her mania to let us understand where her tendencies come from.

HULLFISH: There’s a lot of molding that happens, obviously. Some actors give a huge range and you’re able to say, “I’m going to take this scene in this direction but I could also take in this totally different direction.” Was that the case with this show or was the through-line of her emotion the same for each performance or very similar?

TESORO: I think it was fairly the same. It was one thing that Scott really wanted to make clear about the character in terms of her performance — or in terms of what kind of person she was. It only varied when Anya was still sort of learning where “the pocket” was. Once she knew where “the pocket” was, she was very consistent. Obviously where SHE could go wild is when Beth HERSELF goes wild. That was really actually great, because Anya brought other things to it.

HULLFISH: Have you worked with those kind of performances? Do you like one over the other — where you know where the actor is going to be and each take and each setup is going be fairly similar? Or do you like it when you get the quiet performance and the crazy performance and the very unusual choices?

TESORO: I would say it depends on the scene but it is fun when you get variations — even if it’s slight variations of the same idea because sometimes the slight variation in how they read this word or whatever can take you in one direction or another and with that direction, you have to be clear on the whole of what you’re going for.

So I do like it when you do have variations especially when you have these really great actors who basically get it in two takes or less. So there’s room for them if they have other ideas and they want to experiment.

It’s usually never super-varied because at that point they had discussions with the director and the writer about where they’re supposed to be. So it’s always these minor moves this way or that way.

It is fun when you can choose though. I thought I had more of that when I was on In Treatment actually. There were more variations.

HULLFISH: Some of the places where that comes out is in watching dailies and in trying to figure out where a scene’s going to go.

I’ve heard of people that watch dailies backwards. Other people like to see the progression. What’s your method?

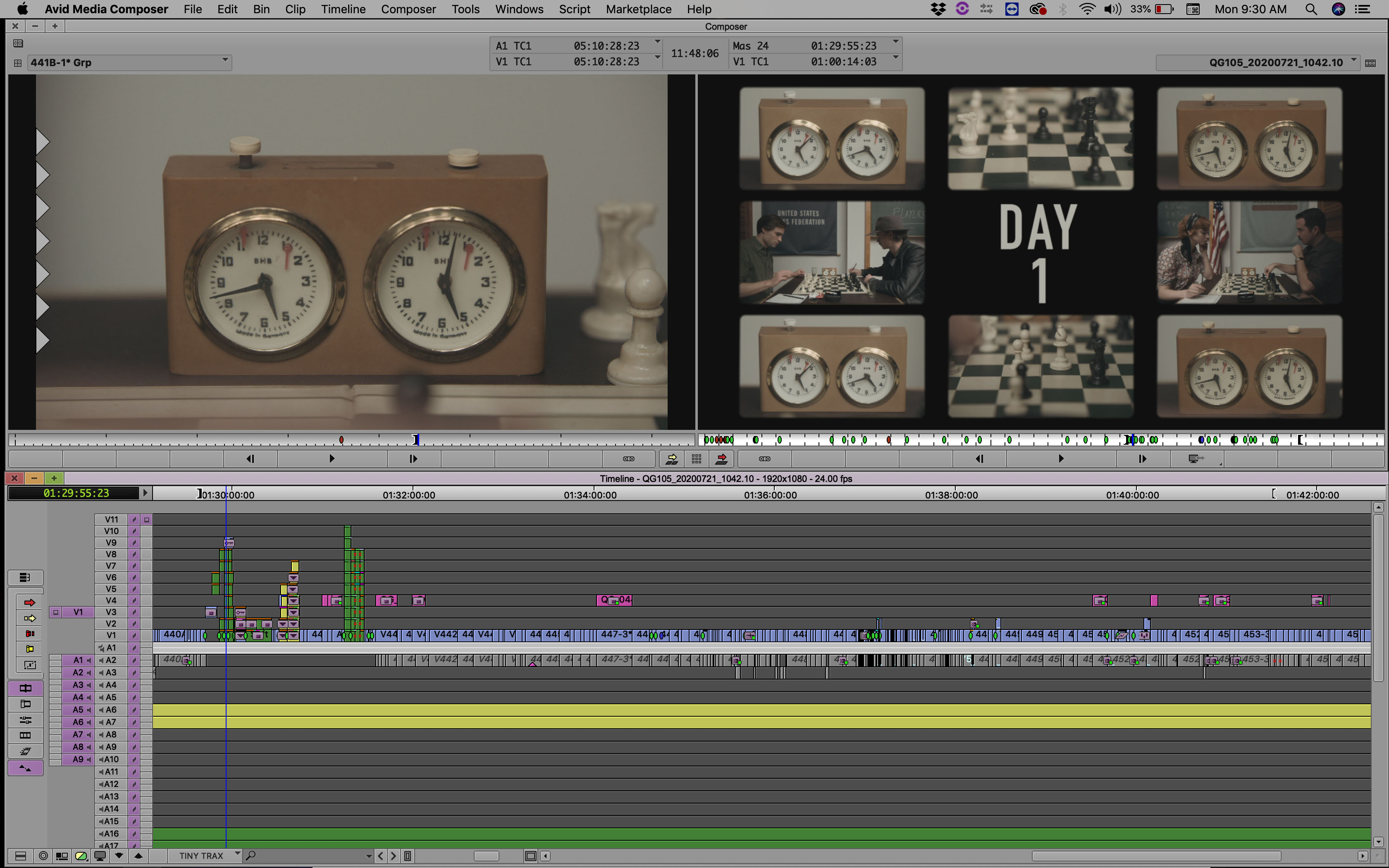

TESORO: The way that I construct my dailies — and I don’t know whether it’s because I like to procrastinate — but now that I’ve gotten the assistants to organize it in this way there’s now no reason for me to procrastinate….

HULLFISH: That’s too bad.

TESORO: Yeah! I usually organize all the dailies of a scene into “phrases” of a scene and you have every setup and every take in a row — for example, line one to five.

I line up all the takes and setups from the beginning to the end of the scene so I can see the whole thing at once in script order and then I call it my Pull sequence. I learned this from Ron Rosen and I know there are a couple of other people to do similar things.

HULLFISH This is exactly my method. You don’t do a line cut but you do three or four lines five lines sometimes based on the blocking.

TESORO: Yes. I love this because I can see that they shot it this way. This is the coverage over here. Oh, there’s no close up. Most of the wide is over here. They did this long choreographed camera dolly thing here. It just tells me the pieces that the director thought they needed overall. Plus, what’s great is, I can see the variations of the performance.

If I have time I’ll watch from beginning to end. From the first take to the last take. But usually they’ll mark the selects and I’ll look at the notes — depending upon the relationship with the script supervisor. And on The Queen’s Gambit we had Sharon Enriquez who is excellent, and she communicates a lot of what Scott thinks in terms of what takes were working for them and not.

So I always look at that first. What did they think on set? And then I’ll watch it and I’ll usually watch just through the director’s selects. If you’ve got five takes and he selected three I’ll do those in order. If I’m in a real rush maybe I’ll just look at the last one, but that’s usually not too much to watch.

We’ll also cut in the things that weren’t “printed” just for safety in case whatever we put in the cut doesn’t work. Then we can look at everything. At least it’s organized. I find that this is great because I watch the whole thing and I see what all the setups are and already in my mind I can sort of know the blocks to play with and be able to cut it that way knowing, “OK, they ended up here and this performance over here was really awesome in this setup. How can I build to that?”

So it sort of gives me an overview before I actually go in there and start putting things together.

HULLFISH: So you’re working off of a selects reel or a pull reel.

What do you do from that point? Do you start making notes? Do you start editing a scene together? Do you start making tighter selects?

TESORO: I’ll pull from a selects reel and I’ll make Add Edits within that reel and I’ll copy that and kind of do it by subtraction. So I’ll start pulling stuff out that wasn’t selected and then with that I’ll usually end up with a third of what the original pull sequence was and then I’ll just start cutting from there. Then I’ll kind of go back over it once it’s sort of rough. Sometimes I’ll get stuck with making a cut too fine without finishing the whole thing but I will eventually go back and start fine-toothing it. But It’s more of a subtraction and then get to cutting.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about the process after the first assembly. Talk to me about how those stories changed when you got in with a director and also how they changed when you finally were able to see context.

TESORO: That is my favorite part of the process because you actually get to see what you’ve done. The number one thing I want to know is how long the thing is, and in our case — because we shot everything cross-boarded — all six episodes were basically assembled together into reels and we could do our run times and I think we ended up at like maybe nine hours and 50 minutes or something like that. That was the first assembly.

Watching it was really enlightening — especially in the first episode — to see how much chess there was and how much we didn’t want the amount of chess that we had.

It was also helpful to see the flashbacks in context because I had just put them where they were planned — while they were shooting — that they could go. We knew we were going to move them, but they clearly weren’t working all the time.

There was a point where I moved a flashback early on I think it was the flashback of the Father to give Alice her pills and wants to take little Beth. At first we thought that scene was too much too soon. It was too long. I moved it.

We struggled with these flashbacks and eventually Scott asked, “What was in the script?” We looked back and he said, “I really think we need to put it there.” This was after really trimming down a lot of other things around it. So now when we put it back, it then felt right.

Because I was feeding Scott the sequences as he was shooting he was already sort of familiar with what the assembly was going to look like.

I think I got to a rough assembly a week after they stopped shooting. That’s when we had cut everything and it was all in order.

Sometimes, in the past, we’ve just hit it reel by reel — so I would break these episodes up into 20 minute reels. And the reason why we do that is because we bring on sound and a sound designer and music editor and the composer has already been writing up to a year prior to that.

What we like doing is getting through a 20 minute sequence and giving it to them and they do their pass. So I don’t really get an editor’s cut per se, where I’m putting a whole episode together and giving it to him with music and sound.

We’re working together towards what we would call a directors assembly. We watched the first three episodes on March 6, because our EP William Horberg didn’t want to wait for the whole thing to be done, but on Godless we waited till we watched the whole thing.

We had a binge with all of our internal people. It was all of post — sound editors, assistant editors, composer, music editor, producer — and we binged the whole freaking thing, which is fine because at that point Scott is making edits on lines and we’re doing a little bit more finer cutting. We’re tracking with the composed music as much as we can. It’s not all of the music, but it’s as much as they’re able to write.

Obviously, what’s great about it is you can hear clean dialogue, so you really understand the rhythms. It’s got the hard effects, but also any kind of design that we might need and in some of those special sequences. You’re not coming at it saying, “Once we get music in here, it’ll be good.”.

HULLFISH: It’s interesting talking about these long watch-downs. You’re cutting it almost as if it’s an 8 hour movie. Is there a challenge to storytelling on that scale or is there a freedom to it? Talk to me about the difference between that and a regular TV show.

TESORO: It’s very different. The advantages of doing it that way is that it’s a singular voice. It feels singular. And you get a lot of consistency of style. It feels like it can be watched that way because that’s how we’re attacking it. You can binge it because it’s meant to go next to each other.

It’s a lot of work logistically, but it doesn’t feel that way when you have only one director who just wants to focus on one thing and isn’t hopping between episides. He didn’t want to do that which is why we decided to do it this way which we did on Godless as well, so we sort of honed this.

Storytelling-wise it keeps it very consistent and I think at some point in the process when we’ve all done a really good pass through all the episodes we are consistently watching it and sending out it out to people that way and they’re watching it as a whole series.

You’re just thinking about it more like every episode is a reel; it’s not episodic the way he wrote it.

Once you have multiple directors you have to have multiple editors. It’s difficult for them to wait because they always want to do their pass as soon as they’ve finished shooting. Having those other directors immediately injects a different style of storytelling.

They do a different kind of shot. I had that experience on Luck, where we had directors that had their own style that were quite established and Episode 4 looked much different from Episode 1, which looked different from Episode 9, but they were in the same world.

I’m not in favor of one or the other. I think I probably like it better when I’m editing the entire series because it feels like you have ownership over the whole idea of it and you can really invest yourself in the series as a whole instead of just caring about your episode.

HULLFISH: When you work on a normal TV series, do you find that you need to be the steward of that show’s style. when you’re working with all these different directors who might have different styles?

TESORO: I think most shows — that is a goal of theirs. Usually you have the overall showrunner trying to add that, so when they’re doing their pass, it makes that overall flavor the same flavor, even if each episode might be different.

As an editor — because there are other editors involved — depending upon who they are and if they’re the kind of people who share ideas and affect one another but usually that is done by whoever is leading the pack.

If you’re doing the first episode you’re sort of setting that tone anyway so you have a little bit more of a say in terms of “this is cut this way and that’s what people like and what people have said this is the show” and then that trickles down. So if you’re an editor in the third position, it’s already kind of laid out for you.

HULLFISH: You mentioned that there is a subtext to a lot of the chess matches. Can you describe how those subtexts affected how you were editing those matches?

TESORO: Let’s talk about her first tournament. This is Episode 2. We’re in Kentucky. The first time that she sits down to play and it’s the only other girl in the tournament. We’re very much learning about what her prescribed place is going to be in the world of chess. We’re introducing the clock. We’re introducing what the timings mean — the writing down of the moves, so it’s trying to walk you through it.

Throughout the next sequences of her playing you have these different characters of chess people that she interacts with — because this is the first time that she’s seeing the kind of players and what their shtick is. So it was really about showing the characters that are there and the final character is Harry Beltik, who we build throughout the episode as being a threat.

And in the first part of that — before she takes her bathroom break — It’s very standard. We want to show that this is the last game; she’s made it this far. Can she stand up to it? Other than this establishing shot in the beginning — it’s the 50-50 that kind of booms up a little bit which is great because within that they’re playing at a rhythm and you can see that he’s very at ease.

He’s shown up late, so we show the clock, she’s very frustrated and and he’s basically sharking her. At some point after we do the boom up we establish that she’s already psyched herself out. We want to go a little bit more internal with her being psyched out by him. At that point we’re not that interested in what’s actually happening on the board. We’re interested in her emotional state and how what he does affects her.

So he’s yawning. He’s got these weird yellow teeth and on top of all of it it, it seems like he’s completely unfazed by any move that she makes, and it surprises her because from the other matches that she’s had she hasn’t had this problem. She’s felt completely confident. She’s felt like she’s ahead of everybody, but this guy — for whatever reason — is really getting to her.

I had to build her to feel like she was about to break down and that she needed to take this bathroom break And how does she make a turnaround here? So I think if you look at the coverage we’re getting a little tighter and tighter and there is a time cut in there where we’re on these really close shots. I don’t think he had wider shots there. I think he didn’t give me the option. He just had this (Michelle frames her face with her hands in a tight close-up.)

Actually, we did have wider coverage but I ended up using these tighter close-ups because I wanted to get in her head more and to lead her up to the, “I’m going to go to the bathroom and take my pill” which she does and when she comes back, Anya’s performance is completely changed.

This is the intense emotional, confrontational back-and-forth between her and Harry and you want to see Harry’s reaction to this. Now we’re in a different part of the game, even though no one has any idea what is happening on the board. It’s right because the chess consultants have made sure that it all is in continuity, but at that point when we want to have this as a turnaround and she’s going to start winning, I start cutting in closer to the board to see these actual matches.

There are times where — just by me watching what they did — I can kind of tell what was an important move especially when Harry goes takes a deep breath — they have a reaction to it, so I could tell, “that’s important.” I went tighter and tighter. I used the sizing to intensify it and to point out what’s important. We stay in tight close-ups, and at some point — before he puts his king down — it’s just a dialogue between between her and Harry and you already know that she’s won without really seeing it play out.

That’s how we attacked most of the matches and sometimes Scott already knew that he didn’t care about what was on the board. For example, Girev, the young boy in Mexico City that she plays — there’s an adjournment, she comes back and the second part of the match you don’t see the board at all. It’s just her getting up making a move getting up and psyching this this young kid out. His performance was so great.

You could just tell where she stood in it and it didn’t matter what was going on on the board. Scott already decided, “OK, we’re only going to show it when he lays his king down.”.

HULLFISH: What kind of visualization were you able to do or did you do for the stuff where she’s envisioning the chess match going on above her head?

TESORO: This was an element in the book that was already kind of drawn out. We would send the plates — the scenes as cut with the empty ceiling and everything — to Chicken Bone, which is our visual effects house and they went round after round with the way these things were going to look.

Scott’s first style idea was for them to watch The Ring — when the creature comes out — and they’d try that, but Scott thought it was too digital. They had to try things and he just had to react to it. They had those sequences for months and we would go back and forth until it just felt right.

Our post supervisor read up on what might be appropriate given where it was in the story, because some of these openings or certain games have characters to them and I think she would be in contact with our chess consultants about what would work.

So before they came up with a style they just delivered it as kind of an animatic because we just need to know what the motion is and: “Is this queen going to come this way in front of camera?” or whatever the animation was and I would cut with that until they could figure out what the style was. But finding the style took forever.

HULLFISH: What was the schedule?

TESORO: It was a fairly long prep and then they started shooting at the end of August 2019 and they shot for 82 days, so they were done around mid-December. Final lock was mid-June 2020. Then we mixed all of July. We were mixing as we were going so it was just finalizing. I think we got done with the mixes in about three weeks for all of the episodes.

I went home at the end of July and they were finishing delivering in September.

I went home at the end of July and they were finishing delivering in September.

HULLFISH: Michelle, thank you so much for talking to me about this.

TESORO: Thank you so much. It was an honor and pleasure.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed, and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

If you’d like to see more great visualized quotes like this, subscribe to my Twitter feed @stevehullfish (or on Instagram)

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now