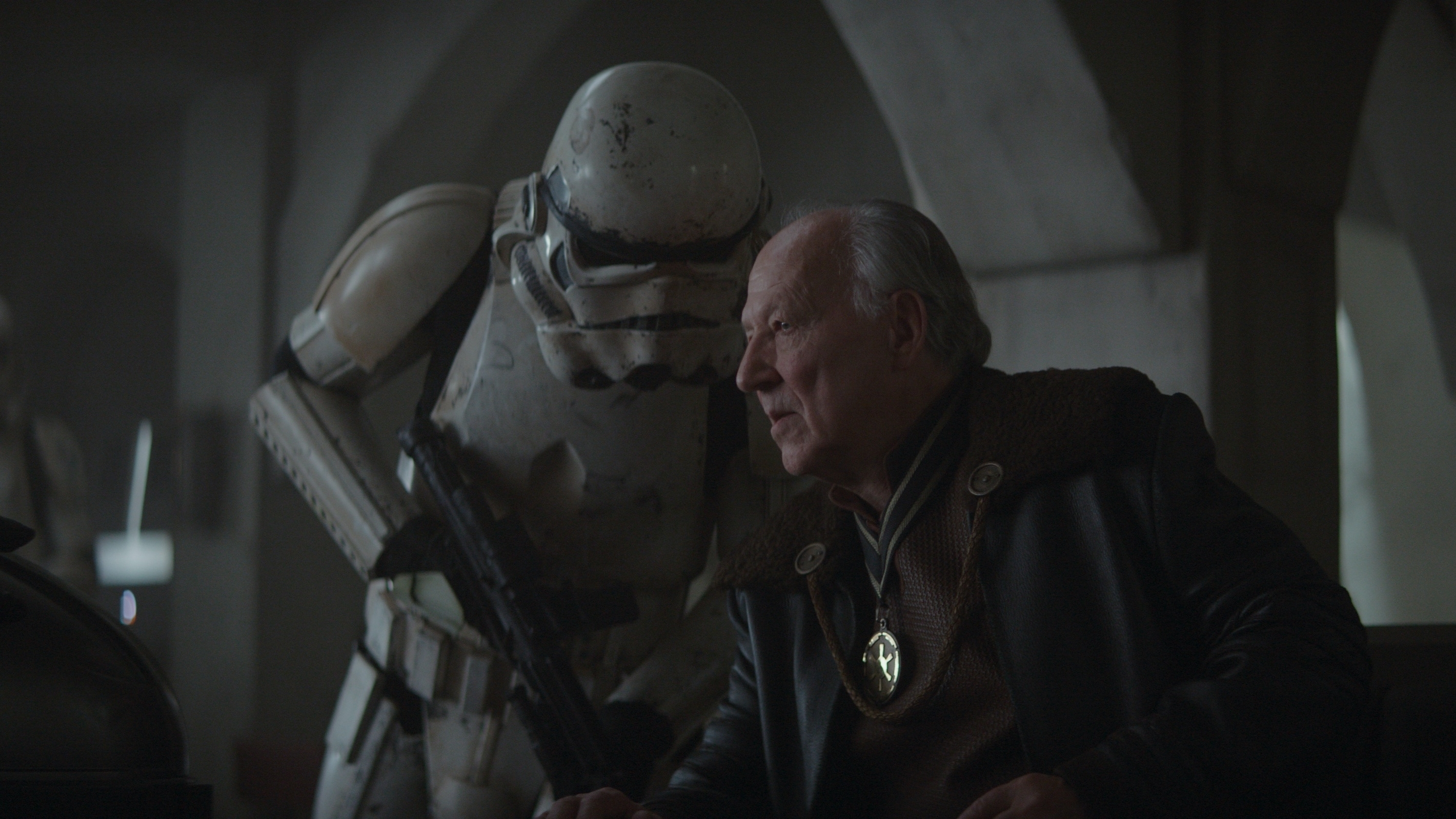

Today, I’m talking with the editing team of Disney Plus’s The Mandalorian which received three of the eight nominations for OUTSTANDING SINGLE-CAMERA PICTURE EDITING FOR A DRAMA SERIES. The nominated episodes were Chapter 2: The Child, edited by Andrew Eisen, ACE, Chapter 4: Sanctuary, edited by Dana E. Glauberman, ACE and Dylan Firshein, and Chapter 8: Redemption, edited by Jeff Seibenick. All four are joining me today.

Dana E Glauberman, ACE, has been nominated for four ACE Eddies for the feature films, Thank you for Smoking, Juno, Up in the Air, and Young Adult. She was named Editor of the Year by the Hollywood Film Awards in 2009, and is the editor on Ghostbusters: Afterlife which was supposed to be out earlier this year and it’s KILLING me that, due to COVID, we have to wait until next spring to see it! She also edited Creed II (which was a previous Art of the Cut interview).

Andrew S. Eisen, ACE was editor on Brightburn, The House with a Clock in its Walls, and The Imitation Game, was an additional editor on Guardians of the Galaxy Volume 2, and an associate editor on The Hateful Eight.

Jeff Seibenick has been a long time collaborator with Rough House Pictures’ Danny McBride and David Gordon Green and has edited their shows Eastbound and Down, Vice Principals and several features including The Foot Fist Way, Legacy of a Whitetail Deer Hunter and Flower. He’s also edited episodes of Cobra Kai, Parks and Recreation and the pilot for Young Sheldon, where he first worked with Jon Favreau, planting the seed for this involvement on The Mandalorian.

Dylan Firshein was a first assistant editor on Solo: A Star Wars Story, The Big Short, and others. He was Additional Editor on Jon Hamburg’s Why Him? and Associate Editor on Tron: Legacy and Valkyrie.

This interview is available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: First of all, thank you all for joining me here. Congratulations on the Emmy nominations.

This series is such a big fan favorite. I’m sure Star Wars fans everywhere just want to soak it all up. How much is world-building a part of the things that you want to show as you’re trying to decide on your episode?

SEIBENICK: The good thing is that we entered a world that was already pretty well established and it was awesome to open the door and play around in this massive area that we were just finding a small little corner of. In terms of editing, there’s a certain style that we all adhere to. Star Wars conventions and Star Wars cliches that Star Wars invented, but for me, personally, the Star Wars world starts and ends with the sound design.

As soon as you can nail in those specific perfect beautiful brilliant sounds that were established all the way back in 1977, all of a sudden that world starts to feel like you’re there — you’re in the Star Wars universe. It’s so exciting to play around in that world.

HULLFISH: In a lot of the episodes that I listened to in season 1 there’s not a lot of dialogue. It’s listening and hearing the atmosphere and all that stuff. I think of some of the big action scenes — the attack by the Walker on the village — how much sound plays a part in the pacing of it and the believability of it.

GLAUBERMAN: When I approach a scene, I don’t have sound lead me where I’m going. I cut to tell the story, even if it’s just shot against a blue screen with a big ATST that’s not even there yet.

SEIBENICK: It was just a light on a crane. Remember? It was a light on a crane for the longest time. That’s what everybody was supposed to be scared of.

SEIBENICK: It was just a light on a crane. Remember? It was a light on a crane for the longest time. That’s what everybody was supposed to be scared of.

GLAUBERMAN: Exactly! It was just a light on a crane. But for me, I literally cut to tell the story and then the sound design comes after. The same goes for music. However, The Mandalorian has kind of inspired me to add more music into my cut after I’m happy with the scene. I don’t do that very often, simply because music can be so personal, so putting in the wrong piece of music can sometimes ruin the viewing experience for the director, especially if they had something different in mind. Generally speaking though, I know that if a scene plays well dry, then adding sound and music later will only make it play that much better.

HULLFISH: When one of the biggest elements in the scene is just a light on a crane, it takes some imagination to cut for story.

SEIBENICK: In the early stages of editing, specifically when we were cutting the dailies, using sound just to sell the story of that scene. For instance, with the IG-11, I would put in the sounds of him walking — like the servos and the clomping feet — just so you knew that he was in the scene or he was walking around behind Mando or even if you couldn’t see him, I felt it was very important to hear that character.

Especially lasers. We got laser effects but I would sometimes — for the big battle scenes — I’d just throw in these really beautiful laser beds that had been designed for the movies that we had access to, just to make it sound like there’s a whole fight going on over there, even though I’m looking at two characters here. The world behind the camera is massive and there’s a lot of activity always happening off-camera which helps flesh it out and gives that sense of danger and excitement the whole time.

GLAUBERMAN: Along those lines, my initial cut is without any of that sound, and then, of course, in order to sell the scene properly it’s good to add those sounds in, but again, I don’t let the sound effects tell me where to cut.

EISEN: I totally understand where Dana is coming from and it’s actually part of the way I was trained. I think we come from the same generation. We both started on film and eventually migrated to the digital world.

In digital, you get a lot more access to things that you couldn’t do when we were on film. Back in the film days, you had a dialogue mag track, you had a sound effects mag track, and you had a music mag track and you didn’t really add the sound effects or music until much later on. You cut basically with your one single production audio track and that’s what we had.

But today we have access to a lot more, and we have these massive libraries. Skywalker was very generous in sharing their Star Wars library with us.

To switch from sound to picture, there were a lot of scenes in Episode 102 that I worked on that were only on bluescreen. There’s this whole chase where Mando is climbing up a Sandcrawler. He’s really just on a wall a few feet off the ground on the backlot just hanging there and punching at air. Nothing’s there and he’s certainly not moving.

The only way I could sell that scene to everybody in my first cut — before I showed anybody — I found the pieces that best conveyed the action I wanted to happen, got them to work on their own which still looked like nothing, and then I did my own postvis and sound work. I took pieces from the previs and I comped them in there to give the sense of motion, environment, and falling debris. Then I did the same with sound, adding the roaring engines, metal hits, and scrapes, punches, and screaming Jawas. After that, I used the exciting temp cue Jeff had used in the previz and cut it to fit the new scene. I feel that the only way that scene could sell is if I had done those visual and sound effects on my own ahead of time.

The only way I could sell that scene to everybody in my first cut — before I showed anybody — I found the pieces that best conveyed the action I wanted to happen, got them to work on their own which still looked like nothing, and then I did my own postvis and sound work. I took pieces from the previs and I comped them in there to give the sense of motion, environment, and falling debris. Then I did the same with sound, adding the roaring engines, metal hits, and scrapes, punches, and screaming Jawas. After that, I used the exciting temp cue Jeff had used in the previz and cut it to fit the new scene. I feel that the only way that scene could sell is if I had done those visual and sound effects on my own ahead of time.

SEIBENICK: And really we have to do a lot of work to sell it to the directors and the producers. If you don’t it’s like, “What am I looking at?” You’re really designing everything from scratch just to say, “This is my rough cut.”

EISEN: And most every director I’ve ever worked with — or producer or anybody in the business — says, “Oh, don’t worry I can look at a rough cut. I understand what I’m looking at.” And I believe they can, to a degree, but then they also start questioning, “Well, where’s this? Where’s that?” And you have to say, “It’s gonna be there. Don’t worry.”

But if I can show that ahead of time using sound effects — like Jeff was saying — I’m not talking about every Foley footstep. I’m talking about things that are part of the actual story that are just as important as picture. For me, I do insist on putting those things in myself, whereas when I need all the footsteps and the Foley, I will ask my assistant editor, Zach Fine, or associate editor Erik Jessen to cut all that stuff in.

SEIBENICK: I’ll tell you we were all weirdly obsessed with getting those Foley footsteps down. When you see Mando walking across the stage floor and you add that subtle sound of the spurs and the creaky wood, it gets down to that kind of minutiae when you’re working in this world. It makes him feel tougher, makes the world feel more real.

SEIBENICK: I’ll tell you we were all weirdly obsessed with getting those Foley footsteps down. When you see Mando walking across the stage floor and you add that subtle sound of the spurs and the creaky wood, it gets down to that kind of minutiae when you’re working in this world. It makes him feel tougher, makes the world feel more real.

EISEN: But that’s all “seasoning to taste” after the fact. It’s not important to have that to sell the scene, so from that standpoint, I agree with Dana.

Then as far as music, also I agree with Dana. I do put it in, but it’s after I feel very comfortable with the cut of the picture. Then you find music to support that picture — as opposed to finding music and then cutting to the music. I don’t think that’s the best approach unless working on a Montage maybe.

HULLFISH: I think there are two separate issues. There’s the sound that you need to sell the scene to someone else, but I also think that the sound can affect the sense of the visual pacing and understanding of the story.

Dana, on that big battle scene with the Walker, what was the production sound like? My guess is that there was very little there. Do you need some kind of sound just to tell the story? Explosions or laser blasts? Do you have to make the sounds in your head at least, or with your mouth?

GLAUBERMAN: I’m much more of a visual editor than a sound editor. A lot of times as I’m assembling, especially a scene like the ATST battle, I AM making those sounds in my head. I know what an explosion would sound like, and I know what a laser would sound like, and so I’m just imagining all of that, much like I’m imagining what this ATST is going to look like. Granted, things might need to be tweaked once the sounds are added, but for the most part, I am judging timing based on the visual, and a bit of the sounds I’m making in my head.

Every single episode, though, was cut in their entirety in previz, which was helpful on many levels, including taking sound effects and music from it. Not to mention that I had Dylan by my side to help me out!

Every single episode, though, was cut in their entirety in previz, which was helpful on many levels, including taking sound effects and music from it. Not to mention that I had Dylan by my side to help me out!

SEIBENICK: The amount of work you would put into an editor’s cut, we did on the previs for every episode.

EISEN: There weren’t eight episodes. There were 16 episodes if you count the previz cuts. That’s what the workload was like.

HULLFISH: Who cut the previs episodes?

SEIBENICK: I started very early in the process. I came in before there was even a post department. I was like THE GUY in post. There was no assistant editor. There was no post producer. It was just me.

When I started getting these temporary previs shots sent down from ILM and they were still working out the process of how they were going to do it. As a couple of scenes from episode 101 came in, and then a couple of scenes from episode 103, and Dave Filoni was overseeing those at the time. Then we hired The Third Floor.

HULLFISH: The Third Floor is the previs company. I actually did an Art of the Cut interview with them because so many people were getting previs and previs editing done there.

SEIBENICK: A great bunch of dudes. Really talented. Awesome. Hard-working guys and they’re always down to get creative and super-involved in everything.

Then they started pumping out previs episodes. I think I cut 101, 102, 103… I did a big chunk of 107. Maybe half of 105. Up until that point, I thought, “Hey, let me cut the whole thing.” (laughter) I was really overzealous because it was such a dream come true, but it didn’t take long for me to realize, “I’m not going to be able to do this.”.

EISEN: A 5-hour massive visual effects feature all by yourself in half the time of a regular feature….

SEIBENICK: I would have made it happen!

EISEN: While you were about to have your first kid.

GLAUBERMAN: Yeah, Jeff, with a new baby.

HULLFISH: Since you had that previs, were you using that in your assemblies to help with pacing or understanding the story as you were cutting the actual episodes?

SEIBENICK: Hundred percent.

EISEN: Yes, 100 percent. Because we had cut our previs — or even if Jeff had cut previs for an episode that I had worked on — that pacing was already somewhat established.

We went through a lot of vetting. Jon Favreau and Dave Filoni and the directors and the visual effects people and the production people sat and watched those previs episodes as much as we would on a finished cut.

We had to get those beats as nailed down as possible before production began because it drove what they needed to create for The Volume.

SEIBENICK: Volume was the name for the giant interactive surround LED video walls.

EISEN: That was very important to visual effects to know where we were going to be pointing the camera and what ILM had to design for those walls/environments/sets.

Jon also wanted to hone his scripts, so a lot of the writing fine-tuning happened in that previs phase based on how the cut evolved. It afforded him the ability to see what wasn’t working in a script and fix It before cameras rolled.

Production usually didn’t conform to what was in the previs, so we obviously went off and did a whole new thing, but certainly, for action scenes — they adhered a lot closer and that’s the whole point of previs in the first place.

SEIBENICK: The one thing that lived in previs I think from the initial previs cut all the way to the final sound mix was the sound design.

FIRSHEIN: That’s true.

SEIBENICK: We would design the hell out of those previs episodes. It’s basically animation so there’s no sound. You miss things like the footsteps. And when you finally get the live-action shots you still want to hear that. And the sounds of guns clicking and gear rattling and stormtroopers talking in their mics. That stuff stayed forever.

It became, ultimately, super-essential to all of us when we were finishing our cuts because for Dana, cutting an entire action scene with a light on a pole is not possible, so that’s where we relied heavily on all the previs, because I don’t know where (the robot droid) IG is standing, and I don’t know where the bad guys are shooting from because they didn’t shoot that yet or it’s going to be CG, so you have to figure that out for pacing and storytelling.

EISEN: And all that work that we had done in previs to do that sound we were not going to throw away once we started getting production dailies. We repurposed it as much as we could.

SEIBENICK: You could concentrate on the picture editing and then almost literally copy and paste the old sound design into your current cut and then slide a couple of things around and boom it’s designed. Move on. Go to the next scene instead of working for a whole other day through sound designing a scene.

HULLFISH: But as Andrew said, that just means you have to edit 16 episodes instead of 8!

EISEN: That’s exactly how it felt.

SEIBENICK: But Andrew, your episode 102 was wildly different from previs to finished product. You couldn’t watch them side-by-side because they evolved constantly from the very beginning all the way to the very end.

GLAUBERMAN: That’s the beauty of what we do. As editors, we get the final rewrite of any story and for me, previs is a guide. I try to follow it, but there is no rule to stick to it 100 percent. Depending on what comes in from production, you’re allowed to change things even though the previs was approved by Jon and Dave.

EISEN: To that point, Dana, the whole point of the previs was to try and nail it all down, but the truth is, once we started getting footage in they we realized that they went in different directions very often when they were on the set. In fact, in episode 107, there was a scene at the beginning where Cara Dune is fighting this bad guy, and they were attached by some kind of electro-tether device. That was a completely different scene. It was Cara Dune having a standoff with a bad guy in a bar. She was playing a chess-like game called Crutches with pieces knocking other pieces out.

SEIBENICK: They looked like floating guitar picks.

EISEN: So I’m sitting at my Avid getting dailies in for that scene that day and I’m looking at the footage thinking, “What the heck! This is nothing like what they planned.” No one had told me that they had re-conceived the scene. They’d clearly been planning it for quite some time because of the whole choreographed fight that’s going on. But I had no idea. I called the director because I didn’t even really understand what they were doing, because, of course, there was no cord and all I see is them standing a few yards apart moving their hips around like some kind of dance. I didn’t understand what was supposed to be happening. They explained the scene to me and once I understood what the intent was I could cut it, and then had one of our amazing assistant editors/VFX editor — Zach Fine — design those cool electric tethers based on the ones from pod race in Star Wars Episode 1. That, and adding cool zapping sounds sold that scene in ways that just the footage by itself could never have done on its own.

EISEN: So I’m sitting at my Avid getting dailies in for that scene that day and I’m looking at the footage thinking, “What the heck! This is nothing like what they planned.” No one had told me that they had re-conceived the scene. They’d clearly been planning it for quite some time because of the whole choreographed fight that’s going on. But I had no idea. I called the director because I didn’t even really understand what they were doing, because, of course, there was no cord and all I see is them standing a few yards apart moving their hips around like some kind of dance. I didn’t understand what was supposed to be happening. They explained the scene to me and once I understood what the intent was I could cut it, and then had one of our amazing assistant editors/VFX editor — Zach Fine — design those cool electric tethers based on the ones from pod race in Star Wars Episode 1. That, and adding cool zapping sounds sold that scene in ways that just the footage by itself could never have done on its own.

SEIBENICK: For a while, Jon (Favreau) actually thought that those were first-pass ILM effects!

EISEN: There’s a lot of imagination that goes on and a lot of things that change between previs and production. But 102 changed significantly from what was scripted and prevised to what the final cut looked like because there are certain things that didn’t feel like they were working for Jon, so we started thinking outside of the box and creating scenes where there weren’t any.

It was actually the most fun episode in that way because we were forced to be very creative and figure out ways to repurpose footage to make it a different episode than it started out as. In fact, 102 was supposed to have one of the flashbacks that Jeff ended up cutting in 101 and 103 and 108.

One of those was supposed to be in 102 and we took it out — because it wasn’t quite contributing to the story and was actually hurt our pacing — so Jeff found a great way to use it in 101 instead and it worked a lot better there. There’s a lot that goes on throughout the editing process and we are fortunate enough on this show to have the time to let these ideas percolate for a while.

HULLFISH: You just mentioned that you created scenes that weren’t there. Can you tell me what one of those scenes would be and from what parts did you build a scene that was not there?

EISEN: When Mando is at Ugnaught’s farm and he’s saying, “The Jawas stole my stuff” and Ugnaught is saying, “you’ve got to negotiate with them.” In that scene, the conversation was quite different than how it ended up. The blocking too was completely different. Ugnaught was at his workstation almost the entire time in that scene, and it was a much longer scene. For whatever reason, it just wasn’t singing for Jon and he was looking for a way to do it differently and be a little bit more efficient with the information being conveyed, and he also wanted to try and play up the humor of the baby chasing (and finally swallowing) the frog.

So I started taking pieces of Ugnaught where he was standing in a certain position where Mando wasn’t and placed him closer to where Mando was sitting repairing himself, and then I comped them together. Some of that conversation where they’re standing there talking to each other, they were not actually talking to each other at all. We reblocked and rewrote the scene in the editing room! Something that complex we would never have attempted in the pre-digital era.

We could put whatever we want in Mando’s mouth. Same for Ugnaught, In fact, we had to reanimate Ugnaught’s mouth to have him say things that he hadn’t originally said. That was a puppet head that was programmed to move in sync to Nick Nolte’s voice. We had to get Nick Nolte back to record some new lines. To add to that this was footage that was shot on The Volume, so it wasn’t bluescreen where it was easy to slip them around wherever we wanted.

I do crazy stuff in the Avid. I Animatte (an Avid effect to roughly rotoscope) around these characters and move and manipulate them to create a scene that was very different from the original all the while using the existing footage. It’s very liberating and it helped elevate the entire episode.

SEIBENICK: It’s the benefit of a scene with a bunch of actors that don’t have faces. You really can do whatever you want in order to tell a story.

SEIBENICK: It’s the benefit of a scene with a bunch of actors that don’t have faces. You really can do whatever you want in order to tell a story.

GLAUBERMAN: Andrew definitely does some wacky things visual-effect-wise in the Avid. In episode 5, directed by Dave Filoni, which Andrew and I cut together, there was one thing where he literally took just the mouth from one take and put it in the take that we liked better for the rest of the performance.

EISEN: The actor had said the right thing in the NG take but never said it again in the good take so we just stole from one and put it in the other. The VFX folks were skeptical because the angles were slightly off, but we pushed them and in the end, it looked great. So yeah, we manipulate stuff.

HULLFISH: Now I want to ask the opposite question because obviously having a main character that has a helmet on all the time has the benefit of “whatever we want him to say, whenever we want him to say it, we can make him say it.” The flip side is you don’t have an expression-filled face. I think of what we do on a typical day, looking at dailies. You’re staring at somebody’s face looking for the slightest clues to emotion. Dana’s pointing at her eyes. You don’t have that with this character. Talk to me about trying to find the emotion in a mask.

GLAUBERMAN: In reference to Mando, I think we were still able to find a lot of emotion without seeing his eyes. You get a different kind of emotion but all it takes is just a little turn of the head or a little body movement or the slightest sign that he is engaged and/or reacting to something that does so much. And because he’s an actor in a mask, we can then put whatever words we want to in his mouth to sell that reaction, which was very helpful.

SEIBENICK: It’s kind of freeing in a sense. It is difficult, but you get such a second chance to re-imagine a scene or a performance without a face. As Dana said, a little cock of the head — you put it in a certain place and it means so much more than if you could see his reaction.

SEIBENICK: It’s kind of freeing in a sense. It is difficult, but you get such a second chance to re-imagine a scene or a performance without a face. As Dana said, a little cock of the head — you put it in a certain place and it means so much more than if you could see his reaction.

I remember there was a scene in 101 right before the big battle scene at the end where the actor was performing it a lot more hectic and frenetic than Jon had wanted. And we wanted him to be a little bit calmer and a little bit more together in that scene. So we took his performance, slowed it down, reversed it, put subtle freezeframes on it. Even just having a motion stop — as long as it’s imperceptible, it makes so much more of an impact and you can manipulate that. You can almost become an extension of the actor himself.

We would be in the visual effects reviews we’d be watching it before they recorded all of the final voices. There had been so many rewrites to so many scenes that I think Mando — in your episode — was played by five different people (group laughs) including Jon Favreau, me, Andrew did, Dylan, and everybody in our whole department was Mando at one time in her episode. In a single scene, you’d hear it jump back and forth between multiple scratch voices.

HULLFISH: Dana, did you do any temping of the Mandolorian’s voice?

GLAUBERMAN: I did not. I really wanted to, but there was nowhere for my voice to fit in.

HULLFISH: Come on! Dana, let’s hear your best Mando impersonation!

EISEN: (Director) Bryce (Dallas Howard) temped a lot of stuff for us.

SEIBENICK: And she was really good. She brought a lot of gravitas to the performance because she’s an actress. My claim to fame is that one of my voices stuck in episode 101. As we were doing the stormtrooper voice recordings, there’s one trooper who says, “We have you four to one!” They tried to record it with 15 different voice actors to try to replace it, and Jon and Dave just didn’t think that they sounded like enough of a little bitch. They said that Seibe wins this one because he sounds the most like a person you want to punch (laughs).

SEIBENICK: And she was really good. She brought a lot of gravitas to the performance because she’s an actress. My claim to fame is that one of my voices stuck in episode 101. As we were doing the stormtrooper voice recordings, there’s one trooper who says, “We have you four to one!” They tried to record it with 15 different voice actors to try to replace it, and Jon and Dave just didn’t think that they sounded like enough of a little bitch. They said that Seibe wins this one because he sounds the most like a person you want to punch (laughs).

EISEN: And… there you have it (laughs).

HULLFISH: I’ve heard of somebody having a punchable face, but I’ve never heard of some having someone have a punchable voice.

Let’s discuss flashbacks. They’re big in this series especially in episode 8, which had an extended flashback sequence. How do you get in and out of those? How do you know when you need to get back to the main story? Who want to talk a little bit about Dawn. I don’t know if you’ve talked much.

SEIBENICK: It was a lot of trial and error because originally the first flashback we’re supposed to see was in 102. After Mando falls off the Sandcrawler, he lands on the ground. It was supposed to flash to white and go to his first flashback. Then it was supposed to come again in 103 during the armor and then it pays off in 108.

Jon nixed the flashback happening in 102 fairly early on after the production because it just didn’t seem to fit. I just so happened to be the editor of all of the Armorer scenes in the first season. In 103, Deborah Chow and I spent quite a bit of time focusing on the rhythm of the hitting and the cuts to things happening in the flashback. She helped design a lot of the previs for those flashbacks. So the Armorer would hit and then that would cut to an explosion in the flashback and so we helped develop — as you said — “a way in.”

Jon nixed the flashback happening in 102 fairly early on after the production because it just didn’t seem to fit. I just so happened to be the editor of all of the Armorer scenes in the first season. In 103, Deborah Chow and I spent quite a bit of time focusing on the rhythm of the hitting and the cuts to things happening in the flashback. She helped design a lot of the previs for those flashbacks. So the Armorer would hit and then that would cut to an explosion in the flashback and so we helped develop — as you said — “a way in.”

When Mando sitting with the Armorer, it was almost like PTSD. The slamming and pounding would bring him back to this past and that would be our way into it. When they cut the flashback out of Andrew’s episode, I started thinking to myself, Shouldn’t we introduce this in Episode 101?

I think we all took passes on it, to be honest with you, but after they shot episode 108, which was late in the schedule, that was when we finally had actual dailies to cut for that flashback. Up until then we were always just using previs and I had found this really great piece of temp music with this rhythm and the banging. That’s an instance where I find the piece of music first because I know it’s going to dictate the rhythm and the pace of this scene,

EISEN: That works for a montage. That’s true.

SEIBENICK: Yeah it works for a montage. I started with the 103 flashback and that was the one that we did the most work on in previs and got that really sick.

Then when (director) Taika (Waititi) directed his episode, he directed all of the flashback stuff. Some of it was different than the previs, some of it wasn’t. But it was brilliant and beautiful and had all the pieces there, but it was “pieces.” It was like a puzzle where every piece is the same color, so you throw it in the air and you see what works.

Then when (director) Taika (Waititi) directed his episode, he directed all of the flashback stuff. Some of it was different than the previs, some of it wasn’t. But it was brilliant and beautiful and had all the pieces there, but it was “pieces.” It was like a puzzle where every piece is the same color, so you throw it in the air and you see what works.

We went back and forth on it a lot — especially to figure out the 101 flashback, because we needed to figure out how much we’d reveal in the 101 flashback and then, what we’d reveal in 103 before the big payoff in 108. So the first one is setting up the flashback. We’re setting up that Mando is a child and that his parents are in danger.

In 103. we’re setting up that it’s droids. It was imperial attack bots that were actually the threat. Then in 108, we paid off with (deleted to keep from spoiling it) which was awesome. That was the evolution of how to tell the story and what pieces to use where definitely helped a lot.

HULLFISH: We have some scenes that we can show and talk about. One of them is from 108 where Baby Yoda stops some flames from a flamethrower.

SEIBENICK: That’s an awesome story about how that came to be. We were in previs and about a week out from shooting. That section of the story hadn’t quite gotten figured out yet. After the big battle scene, Mando gets his bell rung. They go into the building. They find the escape hatch they get out OK. And I remember Taika thought, “We should have like a bigger moment here. We should have a bigger beat here and maybe it should involve the child.” Jon agreed, “We really need the child to do something big here so that he can show his power.”

I remembered back to an old Star Wars video game where there were these clonetrooper specialists and one of them was a flametrooper. I threw that idea out and Dave perked up; Jon perked up; and we started looking online for these flametroopers. This room with the three heavy-hitters on the show and they’re getting excited like kids. Then Taika said, what if the baby stops the flame and Jon said, “Yeah!”

Then they went to The Third Floor guys — the previs guys — and this is before we were even in our offices! We were still weeks away from shooting. The Third Floor guys started it right away. I got that footage within the next four or five days, cut it together. The inception of that idea took probably two weeks and it went from nothing to fully realized in two weeks and it was awesome.

HULLFISH: I’ve got a scene from episode 104 where Mandalorian and Cara Dune have a big hand-to-hand battle and Baby Yoda shows up at the end.

GLAUBERMAN: Cara Dune, played by Gina Carano, is a former MMA fighter, so she did all of her own stunts, which is amazing, and she was totally into that. Cutting that scene was actually a lot of fun. Cutting a scene like that is pretty straightforward because the choreography is spot on.

There were several cameras shooting at the same time and it was just cutting from angle to angle, but there is also a little bit of comedy in that scene with baby Yoda showing up and sipping soup which — at the end of the day — I never thought that that would be the biggest meme going around town of the entire show.

That was a fun scene to do and it’s all about timing in terms of the comedy at the end.

FIRSHEIN: Having her know how to throw a punch, take a punch, it made such a difference in terms of how you cut stuff together. Often, you’re trying to cut around the actors doing it because they’re not throwing the real punch. They’re being careful. They don’t want to get hit.

HULLFISH: I’m sure that having someone that can do their own stunts is a help for you. What’s the difference between fight scenes you have cut before, that needed a stunt performer.

GLAUBERMAN: For stunt performers or even actors who are doing their own fights, it’s all about where the camera is situated, as you can sell a punch better if the camera is not perpendicular to the actors because if it is, you can clearly see a miss. Rather, if the camera is a little bit over one actor’s shoulder, you can sell the hit with a sound effect a hundred times better than if you didn’t have a sound effect. So in that regard, I kind of go back a little bit on what I said earlier. In a scene like this, sound effects are a tool to help sell a fight whether it’s real actors or stunt actors.

HULLFISH: How wimpy were the production sounds for that fight?

HULLFISH: How wimpy were the production sounds for that fight?

GLAUBERMAN: I don’t even remember, do you, Dylan?

FIRSHEIN: They basically don’t exist because obviously no one’s really hitting. The only thing is her actually going, “ooof!” Or Pedro is recorded for it. We had him record ADR. He did his efforts. I think we had her do the efforts. I think we used as many as we could from the actual production.

HULLFISH: For those who might not understand what the word “efforts” mean, could you explain what an “effort” is from an actor?

ALL SPEAKING OVER: Do an example! “Oooh!” “Uhnnn!” (panting) “Whuuuuu!” (basically making the sounds of the “effort” of a fight)

EISEN: A funny story about efforts: In Episode 107 Pedro (Pascal, The Mandalorian) arm wrestles Cara Dune with Baby Yoda is watching (and feels like that Mando is being threatened). So Pedro is doing his ADR of efforts for that and he’s grunting away and finally says, “It just sounds like I’m taking a shit!” We dialed it way down in how it was cut and mixed so it just sounded like he was struggling.

HULLFISH: Can we talk about the mudhorn scene? Tell me about cutting that scene and making it pay off.

EISEN: It was definitely something that was designed by the director Rick Famuyiwa during previs. The intention was laid out in previs although what ended up getting shot didn’t quite match the previs, and we worked that like a piece of clay to get that moment to really, really work.

Part of that — again, I’m gonna bring in sound — because part of it was having the sound disappear at just the right moments. The mudhorn is making noise and it’s the standoff, and Mando is down and out, and the way to really sell that is to get inside Mando’s head. What is he feeling? So by sucking out all the sound, it forces you to focus on him. Even though he’s not doing a lot, you can see that he’s struggling — even just to lift up that knife as a last-ditch effort despite knowing it’s no match for this beast.

We just looked at it over and over and over again, mined the dailies, and kept tweaking the cut to get just the right rhythm and the right sensibility to get that scene to play the way it does. It was a little bit like a dance and we took a lot of time with it and we got there.

I got hired on this show and I had not really done TV before and my understanding of television was that they shoot an episode in eight days, you finish cutting it in eight days and it gets handed off to the sound people, visual and music, and it’s done. It’s an assembly line that moves very rapidly.

We put as much time and effort into these cuts along with keeping the directors around for as long they were needed or wanted to stay (though Jon and Dave as showrunners still have final word). It’s as much like a feature as anything I ever worked on before, so we had the luxury to really hone these scenes and not just rush through them. So it was an evolution, but that particular scene we just kept playing with over and over and over again until it started to feel like an emotional scene, not just a straight action scene, for all three characters involved.

HULLFISH: Did the directors get more than their typical DGA 4 days with the edit?

GLAUBERMAN: Kudos to Jon and Dave for really treating this show very much like a feature just in terms of process. They really wanted to keep all the directors around as long as they felt they needed to be included.

As far as the editors go, they kept all of us involved in every step along the way, whereas on a traditional episodic show the editors cut their episode and pass it on to the next department — sound design, music, and so on — and generally speaking the editors don’t get to see their shows all the way through to the end with final mix.

SEIBENICK: We were the curators of our episodes because there were so many moving parts that needed to be paid very close attention to timing and pacing. When the VFX would come in they’d be just slightly wrong because when they farm out these shots they’re not sending full cuts or scenes, they’re working on a shot at a time but that shot doesn’t work with that shot or with that shot because of where the guy is or what he’s looking at. So we would catch that. Jon might not catch it. Dave might not catch it, because they’re in a review room watching pieces and parts of every episode every day for X amount of time.

And it came down to the same thing with the sound design. We had lived with it for so long and dialed it in for so long that if there was something missing or wrong that didn’t work for the story or the worldbuilding, etc. And then we would be able to say catch it because we were there from the very beginning all the way to the very end. I love being that involved in every aspect of the production.

EISEN: It’s pretty much the way it works in features where the editor is involved at every single stage. So it was very familiar to me. I was very nervous going in, thinking it wouldn’t be familiar to me, but it turned out to be exactly what I’m used to.

SEIBENICK: I’ve never had the experience of being so involved with the visual effects process. I’m always the guy that supervises the sound mix — that’s definitely my favorite part of the whole process — but to be there for the evolution of every single shot in your episode was so exciting. It’s such a joy to see it every step of the way and be there as a part of the process.

GLAUBERMAN: Another great thing about it is we were all under one roof and so we were able to hop on over to visual effects and give them notes and our reviews were literally in a tiny room with what seemed like 27 people!

FIRSHEIN: And these days, it’s 27 people on a Zoom call.

GLAUBERMAN: Exactly!

EISEN: There was great camaraderie between all departments too. That’s another thing very important to say. This show is very special. Sometimes you don’t always get along with everyone, there are different personalities. This is just having fun every day. It’s hard, hard work but everyone’s having fun.

HULLFISH: We already talked a little about the scene with the Walker attack on the village.

So you start with previs. Eventually, you get dailies that are just a spotlight on a crane. At what point do you say, I would rather have the light on the crane than previs that looks like a Walker? And talk about building the anticipation for when it steps into the water.

FIRSHEIN: That scene was one where the previs never really got to the point where it had nailed everything down, so there was a lot of work still that went into it. They got to a point where they knew what they wanted to shoot for production, but then there was a lot of room left.

So, for example, we spent a lot of time improving where the ATST (Walker) actually walked out of the forest — to really build out that moment — where it takes some time. Then the trees start to move. A real like King Kong kind of moment. That was always the reference.

The same goes for the Walker going into the water. We always referenced Robocop where ED209 is trying to go on the stairs. We all watched it and we’re trying to figure out how we could make it feel like that and just give it that kind of fun.

As far as choosing whether to use previs or not, in that case where we needed it, we used it — for things like where it’s falling and there’s nothing there and we need to see something to sell the story beat, but a lot of times, the light actually did the job. It was easier — once we set it up at the beginning — to then use the lighting and the viewer could fill in the holes until we had VFX, but that’s a big place where sound helped us out a lot.

When Dana and I were working on the initial cut you just need to focus on telling the story, once we started putting the sound in, that was when people could then think, “OK, it’s walking here. It’s doing this. Oh, it’s falling. The turret’s turning so we have to watch out.”

GLAUBERMAN: As the ATST is walking out of the forest, when we first cut to that big wide shot to show the distance between ATST and the villagers, it didn’t look very far, so we needed visual effects to help us out to make that distance look further than it actually was in dailies.

The other thing that we worked on a lot was the ATST stepping forward and then falling into the water. That was worked over and over and over again. “Does it take a step forward and then pull back?” That was a big part of editing in terms of building the anticipation and building the tension of when he actually falls in.

The other thing that we worked on a lot was the ATST stepping forward and then falling into the water. That was worked over and over and over again. “Does it take a step forward and then pull back?” That was a big part of editing in terms of building the anticipation and building the tension of when he actually falls in.

HULLFISH: Were those questions about what shots you wanted things you needed to request through the director to create in VFX? Or were those things that were in the dailies or already in shots that VFX was delivering in some form?

GLAUBERMAN: Some of it was there in the dailies some of it was not. We had to create some beats and some moments in visual effects to sell it.

FIRSHEIN: As Andrew mentioned, we did a lot of stuff where we’d repurpose a piece or we found some other thing where we’d run it in reverse. Or we’d reposition it over here so it works differently. So we tried to use it where we needed to, to get the story across, and then turn it over to VFX.

EISEN: And that scene in particular — VFX had a big contribution in terms of designing things that weren’t anywhere. Like, we needed their input to create a lot of that. We would just sit in a VFX review and brainstorm, like, “What do we need here? What’s missing?” And based on that they would deliver exciting shots that we could cut with.

FIRSHEIN: And we’d talk to the animation supervisor, Hal Hickel, and ask, “Hey, what if we did this?” And he’d say, “Yeah! Let’s try that.” So we’d send him a cut and ask, “Is this something you could get behind?” He’d say, “Yeah. I can get behind that. Then maybe I can do this.” It made it a little bit easier if we had to try to sell something to Jon and Dave that we could at least say, “Hey, we’re all on the same page. Would this work for you guys?” We had already talked it through so we could be on the same page.

FIRSHEIN: And we’d talk to the animation supervisor, Hal Hickel, and ask, “Hey, what if we did this?” And he’d say, “Yeah! Let’s try that.” So we’d send him a cut and ask, “Is this something you could get behind?” He’d say, “Yeah. I can get behind that. Then maybe I can do this.” It made it a little bit easier if we had to try to sell something to Jon and Dave that we could at least say, “Hey, we’re all on the same page. Would this work for you guys?” We had already talked it through so we could be on the same page.

GLAUBERMAN: It was a very collaborative effort.

SEIBENICK: And sometimes our cuts would have a freeze frame with a block of text in the middle and kind of imagine the timing and then they would come back.

That’s one of the reasons the editors needed to stay on so deep into the process because they would come back with these new shots that we just designed and the timing would change or else we’d record ADR and Jon would have a new line pitch and then that would make the scene longer or Ludwig would write a piece of music and it would be so good we wanted to extend the scene a little bit so it could end sooner or longer. It was constantly evolving all the way up into the very last minute.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about the “Don’t touch that” scene where Baby Yoda is in the cockpit with Mando. How difficult is a scene like that to cut when you’ve got — I’m assuming a puppet and you’ve got a guy in a mask and it’s dark and there’s not much to see.

GLAUBERMAN: That scene was challenging because there’s no dialogue. And — as you said — there’s a guy in a mask and a puppet. So you need to really create the moments to sell the humor and to sell what’s going on and to sell the charm.

It was just going through dailies and looking at every little moment that could be used that tells the story. That’s what we do as editors: we go through dailies and look for moments to tell the story, and that was the perfect example of that.

HULLFISH: There’s a tremendous need for an editor to have social skills and collaborate. How much of your job is not at the keyboard?

EISEN: I would say a significant amount of the time.

At the beginning, you’re by yourself in that room and it takes a lot of time to just go through those dailies and put it together. You don’t want anyone else around. You just want to be by yourself and try to get that nailed down.

Then you bring in your director and he sees it for the first time. You cringe. She’s cringing…. (laughter) But from that point on that’s when the collaboration starts and you definitely have to get along with your director, you have to be able to collaborate.

You may have done something you thought was the bee’s knees and she says, “That’s just not working for me.” In your mind, you might want to say, “Well I don’t care! This is way better!” But you can’t do that. You have to learn to work with people and to collaborate and to compromise.

And if you really feel strongly about something, in a very diplomatic way you explain WHY you think it’s better and then you can work through it. But ultimately, if the director wants something, the director is going to get what he wants.

And if you really feel strongly about something, in a very diplomatic way you explain WHY you think it’s better and then you can work through it. But ultimately, if the director wants something, the director is going to get what he wants.

Then the same thing happens at every stage along the way. You have your animators, you have your mixers, you have Jon and Dave. It’s very important to try to be as diplomatic as possible and to be able to articulate what it is you want to say and what you’re trying to tell, especially when they don’t really understand the point you are trying to convey.

There are several instances where Jon would say, “Why did you do that?” I’d say, “Well, this is why.” And Jon would say, “Oh! I get it. I see. OK, fine. Let’s move on with that. That’s great.”

SEIBENICK: One of Jon’s favorite things to say was, “Why did you do that? I didn’t go to film school.”

EISEN: Everyone has different personalities and everyone has their own approach to how they do it. We got along great. We’re really a family and the more time we spend together the more it becomes that way.

SEIBENICK: One of the biggest lessons I learned was curbing my enthusiasm.

SEIBENICK: One of the biggest lessons I learned was curbing my enthusiasm.

I had you know no shortage of ideas. Not all of them were great. I’m a kid in a candy store. It’s Star Wars. It’s been my lifelong dream to work in the Star Wars universe. After a few too many suggestions on my part, I think Jon said, “You know what Seib? We got this.” So I have to sit there and let them talk and get through their thing and when there’s a chance I’ll pipe up.

HULLFISH: I want to ask about the concept of ownership. You do not own this. You are a craftsperson working on someone else’s project whether that’s the showrunner or whether that’s the director, whether that’s the studio.

But we still “own” it, right? In our hearts, we own it. How do you walk that line between wanting ownership because it means you’re invested and knowing that you can not have final say?

SEIBENICK: My editor’s cut is my best foot forward and I’m going to do everything I can to make it the thing that I want to see on screen and then I pass it off and that becomes the point where it becomes the collective. But when I get those dailies and when I’m in the dark room poring over footage and dailies and sound effects, that’s when it’s mine.

GLAUBERMAN: I find filmmaking to be very collaborative so my assembly is very much a blueprint. Generally speaking, in my assembly, I do not take out lines or take out scenes or rearrange things because I feel like my job as an editor is to deliver a cut to the director as scripted and then at that point we collaborate to bring their ideas into what I have already created; it’s at that point that we decide together to lose lines, scenes, or change things around. And to collaborate with Bryce Dallas Howard on Sanctuary, as well as Jon and Dave, was just an incredible experience.

FIRSHEIN: I agree with Dana. Same points. The only thing I’d add is just that it’s really critical for people to know when to put your stuff out — as Jeff said — and when to be able to step back. I think that’s one of the big things that as an editor I’m constantly fighting with and learning — just to know when to do that. When to push back or to say, “This is your time. We’re going to do it the way you want to do it.”

FIRSHEIN: I agree with Dana. Same points. The only thing I’d add is just that it’s really critical for people to know when to put your stuff out — as Jeff said — and when to be able to step back. I think that’s one of the big things that as an editor I’m constantly fighting with and learning — just to know when to do that. When to push back or to say, “This is your time. We’re going to do it the way you want to do it.”

Sometimes you hear a director’s ideas and you think to yourself, “That’s not going to work!” Your mind is so busy thinking about how you can make it work, but once you get into the footage you see that actually you CAN do it.

SEIBENICK: You see, “Actually, that TOTALLY works!”

GLAUBERMAN: We — as editors — might think it’s a terrible idea and want to push back but also as editors it’s our job to try and make that idea work as best as we can. Even if we know that it’s not going to work we have to show the director or the filmmakers WHY it doesn’t work, because they’re not going to believe it doesn’t work unless they see that it for themselves. Like Jeff and Dylan just said, it might be the greatest idea ever that we didn’t think of, but that’s where the collaboration comes in.

HULLFISH: And even if it doesn’t work it can still lead you to the right solution.

ALL SPEAKING OVER: Oh yeah. Yeah. Yep. Totally.

EISEN: I take very strong ownership of my cut but I will never push to the point where I’m going to get in an argument with someone. If the director wants — or Jon or Dave or anybody feel strongly about something — I absolutely will defer to them. There’s no question about it.

Everyone’s really smart. It’s very subjective in a lot of ways. Everything is subjective — the way your taste buds are subjective — so the fact that they really want something is really important.

We do make a lot of contributions and directors see things that they didn’t think of and they see that’s a great idea and they take that too. So it is a back and forth but ultimately the ownership does belong to Jon and Dave. Bottom line. I trust in the process so much that when they really like something and want something I know that that is the right way to go.

SEIBENICK: Early in my career when I was working with my buddies on the first season of Eastbound and Down, I didn’t have very much experience in editing. I waited for them to tell me what to do. It was a real push and pull for a while because I asked, “Why aren’t you guys directing me? Why aren’t you telling me how you want the scene to be?” They said, “Seib, we didn’t hire you because we want you to do what we want. We hired you because we want to see what YOU can bring to this.”

That’s the best bit of advice I’ve ever gotten I think. Now I take ownership of my cut because it’s my opportunity to show them what I think I would do, but I don’t deviate from the script or rearrange things, but I cut the way that they shot the best way that I think it should be. And then it’s time to bring them in and collaborate and make it all together. But up until that point, we do get that little sense of ownership because that’s where our chance to shine and pitch our best ideas is, and then after that, it’s, “Let’s see how to make it better.”

EISEN: It was really fantastic speaking with you. Thank you so much.

HULLFISH: Thank you all for joining me. It was wonderful talking to you I really appreciate all of your time.

GLAUBERMAN: Thank you so much, Steve.

GLAUBERMAN: Thank you so much, Steve.

SEIBENICK: It’s always a blast.

FIRSHEIN: Love your site.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.”

This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed, and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now