I had the good fortune of meeting Terilyn Shropshire, ACE, when I moderated a fantastic roundtable discussion that was set-up by Simon Smith. That’s how I wrangled her to do this interview that had been requested by SOOO many readers since the premiere – or maybe even the first trailers – of The Old Guard hit on Netflix.

Terilyn’s credits include another recent killer action flick with a strong female action lead, Miss Bala. She was an additional editor on A Wrinkle in Time (which was a previous Art of the Cut interview). She edited the extraordinary documentary, The Secret Life of Bees – which had been on my wish-list for Art of the Cut interviews when it came out- and a fantastic feature called Love and Basketball, which we also discuss in this interview. Her TV credits include episode 1 of Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us, among many others.

This interview is available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: What is the experience of watching it like that instead of the way you’ve been watching it: critically — where you know you can do something, you can give notes — now you’re done.

SHROPSHIRE: My first reaction was I’ve gotta get a better soundbar!

It was one of those things where one of the last send-offs (director Gina Prince-Bythewood) and I did was to go over to Deluxe in Burbank — social-distanced, mask on — to watch it and listen to it on the big screen. It was something that we both desperately needed. It was extraordinary.

We had gotten a taste of it during our final stages of the mix where — for the purposes of hearing the mix and doing fixes we did go to a facility and social-distance and do that process, but for us to just sit in a theater and watch the movie was extraordinary knowing that it would probably be a while before we were able to do that again.

Streaming on Netflix, it is something extraordinary to watch because the film does have such scope, and yet I feel that it still reflects that in watching it that way.

I was able to just enjoy it. Aside from my sound issues, it was good. It was really good to just kind of sit back and enjoy it and see how it translated to be perfectly honest — from what I was used to hearing.

HULLFISH: How did you monitor audio in the edit suite?

SHROPSHIRE: I monitored it Left-Center-Right. I have not gone into that world yet of setting up everything in a 5 1 situation. I found it to work really well for us and certainly I think the assistants appreciated that I wasn’t trying to keep 5.1 going during the entire process.

HULLFISH: There are very few people that I’m talking to that try to do a 5.1. It’s just so complicated and so many extra things to think about. I think most people are doing LCR at the moment.

Did you have to do any of this editing from home?

SHROPSHIRE: Well we were imminently locked. We had a meeting with the crew on Friday the 13th. I remember it specifically because we were starting to kind of hear and be aware of the rumblings of people heading home and closing down and drives being bought up and so I really wanted to have a conversation with the crew about how they were feeling about everything.

By that following Wednesday, we were all pretty much in our own individual spaces. Gina and I had done most of the heavy lifting but we still had notes coming in from producers and a few things to kind of wrap up.

Because I felt like I was pretty much done, I didn’t come home with the full system. I came home with an iMac monitor and basically two drives. The challenging part for us was, we hadn’t scored yet. Gina and I were literally two weeks from heading to London to score with our composers and that, of course, got postponed.

We were still working on ADR — scheduling of the actors to do ADR and you know how challenging that can become. Our post supervisor, Ruth Hasty was still making calls and trying to coordinate where everybody was, and so that had to be dealt with.

And we were still very deep into visual effects reviews. So all of those elements from ADR to mixing to scoring — all of that had to be done from our isolated quarantined spaces and we had to figure out a way to make that happen. And deliver the film at the caliber that we all intended it to be.

HULLFISH: That it WAS.

SHROPSHIRE: Thank you!

It was a lot of heavy-lifting for everybody. My assistants were amazing.

HULLFISH: Can we give a shout out to them?

SHROPSHIRE: Yes. Corinne Villa was my first assistant. Angela Latimer was my second assistant. I had Sean Valla as VFX editor. Ethan Henerey as assistant VFX editor. Our music editor was Jen Monnar.

All these people were just amazing and really, really stepped up because they really were the people that had the bulk of that post-production delivery turnover — having to make countless QTs for everybody who needed them to get the film done.

It was interesting because when we all got to our separate homes I think we realized how robust — or not robust — our internet was. I remember the first week, Corinne — who is the calmest person, she is just this powerhouse — was so quietly stressed about the fact that her internet at home was not ready for the amount of work she knew that she had to do, and so for that first week — as she’s trying to get Spectrum or TimeWarner, whoever was to come in and bump that up — a lot of the work was having to go to Angela. And Angela just handled it so well. I could not have hoped for a better crew getting through this during COVID.

HULLFISH: What do you do, or how can you help those assistants to move up and increase their skills?

SHROPSHIRE: Well, I think the first thing you have to do is to find out what they want. To get a sense of who they are and where do they want to get to? Because not every assistant wants to be an editor. They may have other goals. They may be perfectly happy pursuing their work as an assistant.

Very early in my career, it was one of my first jobs, and I was working as a second assistant and I remember that the production coordinator on the film — because the production office was actually right adjacent to the editing room — and when she needed to talk to the post crew you’d hear her yell, “Editors! Editors! Get in here. I need to talk to you.” I remember that because even though I was a second assistant and there was a first assistant and then there was the editor, she called us all “editors” and I always think about that in terms of the mind-space of the people that are coming in to work alongside me — to help me and allow me to be my most creative self.

The first thing I try to do is to get a sense of who they are and what they want and then through the course of that working relationship and seeing how they are working within their responsibility, if I see that it’s somebody who is working very hard and very passionate about the work and also what we’re doing, I usually try to kind of put them in a space where they can either work with me; work with the director; be in a room at times when the two of us are working together; bring them in for feedback — because I think part of preparing an assistant to get in the chair is not just the tools.

They’re going to learn the software. They’re going to learn how to do any number of things within their daily responsibilities. What they’re not necessarily going to learn is how to communicate with a director; how to communicate with the producers; how to conduct yourself from a political standpoint.

When you have a lot of different entities coming in to either look at the film, evaluate the film, talk about anything. What’s great about Gina — the director I worked with on The Old Guard — is, she’s someone who wants feedback from the other people that she’s working around, so anytime we would finish a cut, she’d bring the entire crew in and sit them down and we would show them something and then she would encourage everyone to share their opinions.

I would do the same even when Gina wasn’t there. With assistants sometimes there’s a comfort level to being able to talk to me in what they would see as a safe space and give me feedback.

I notice sometimes there’s a little more hesitation when they’re actually in the room with the director and I think that part of my responsibility is to communicate to them that they should feel free to supply constructive criticism and talk about how you express yourself in that kind of space.

So that’s part of the things I do. Often when I was working on a scene and Gina wanted to review dailies she would go into Angela’s room. We set up Angela’s room with a large monitor so Angela often would be having to build string outs of performances and that type of thing and then she and Gina would narrow it down to the things that Gina wanted me to then go take a look at.

I tried as best I could to keep them involved in our process.

HULLFISH: And for them to be visible, too. That’s a big part of it, correct?

SHROPSHIRE: Exactly — for them to be visible; for Gina to know that if I’m not available she could go to Corinne or she could go to Angela. If she needed to do something with visual effects, go down the hall. Sometimes I’d push her down the hall! “Deal with that with Sean! I’ve got stuff to do here!” (laughs)

So she got very comfortable with working in that environment and then as you start to look at what your assistants are doing — and knowing what they’re doing on the side — Are they cutting something on the side? Are they working on something else?

So she got very comfortable with working in that environment and then as you start to look at what your assistants are doing — and knowing what they’re doing on the side — Are they cutting something on the side? Are they working on something else?

A lot of times I will get calls from people looking for someone to cut a short or someone is about to work on a documentary and I really try to kind of keep my eye out and be aware of what both the assistants I’m working with now and the assistants I’ve worked with in the past — where they are in their careers or what they’re doing, and a lot of times I’d like to try to recommend them.

But I am also very careful because I don’t want to put anyone forward that I can’t stand behind or support. Sometimes directors are looking for a certain resumé and often I’ll say to them, Look. This person’s got talent. They just don’t have the opportunity yet. They haven’t had enough opportunity. If you decide that you want to go with somebody like that, I will be their support system. I will be there…

HULLFISH: Wow. That’s powerful.

SHROPSHIRE: …to support them, because how else do you get those opportunities? And that’s because of what I had when I was growing up in this business. I had very, very supportive editors who gave me the opportunity to cut, gave me the opportunity to watch what they were doing, and so I think a lot of it has to do with how you grew up. Who were the people that raised you? And I had some really lovely people.

HULLFISH: Who were they?

SHROPSHIRE: I worked with Howard Smith (Glengarry Glen Ross) I was his first assistant for a number of years. I worked with Paul Trejo (Twin Peaks, 2nd Season), Earl Watson (Prison Stories: Women on the Inside), who’s no longer with us, unfortunately — Anne Goursaud (The Two Jakes) was someone who I only worked with once as an additional assistant. But she remembered me and when she transitioned from editing to starting to direct herself she called me to edit her first three films.

So these are the type of people that — through their advocacy of me — I was able to work my way up the craft and I’m really, really grateful.

HULLFISH: Hopefully all of us are grateful to those that brought us up and had faith in us. I love that.

Let’s talk a little bit about the craft itself in this movie. What do you do when you’ve got dailies? What have you asked your assistant to prep for you? And then you walk in, you grab your coffee or whatever and what do you do?

SHROPSHIRE: I have asked them to prep my dailies and on something like The Old Guard — in certain scenes where you knew that you had multiple cameras going — I was very specific that I wanted group clips (Multicam groupings) and this is where I kind of trusted that they would have a familiarity with what the cameras were doing.

In some cases, we had these GoPro headcam cameras that we had to deal with or on the kill floor where we had cameras EVERYWHERE. Just being able to create those groups that I could sit and watch.

So generally what I would do is I grab my coffee — or my tea because I was in London — and I would just start from the beginning. I don’t have a notepad — at least directly in front of me — because the first time I watched dailies I really don’t like to take notes. If I have the time NOT to, I prefer just to watch it and be that audience member.

Obviously I know the scene that’s coming in, but beyond that, I just like to watch and go through the dailies. There are days where I feel like I spent four hours or something just watching dailies, but it really does help me to get myself in the emotional space to cut the movie.

Obviously I’m making sure that I see everything I want to see — or that I FEEL that should be there — and if I’m starting to get a certain degree of anxiety as I’m going through the dailies towards the end and I’m not seeing what I need to see, then that becomes more of a search. At a certain point — after you’ve seen so much of the scene from different angles — you start to kind of put it together in your head. And then you start to make sure that there’s a particular detail or reaction or that there’s a certain line that you really want to see in a certain space and you hope that it’s there.

So that’s kind of my process and it’s hard these days but I cannot NOT look at everything.

Back in the day, we used to have circled takes and sometimes I think about when we didn’t circle take everything and there was this thing called “B-neg” that never got printed up.

HULLFISH: Much of my listenership are people who know what a term like B-neg is, but for those who don’t know what B-neg is, could you explain it?

SHROPSHIRE: In the days of film, when they were shooting multiple takes on a set, there was something called circled takes. They might shoot 4 takes of something and the director will decide on the set, “I liked takes 2 and 4” which meant that 2 and 4 were the ones that were printed up to print stock to be delivered to the editors. The other takes were left as negative. They were not printed for us to use.

Generally, you did not see those takes visually as an editor unless it was a decision that — for whatever reason — we needed to print up those takes. And those takes were called B-neg. Now in our digital world, everything is brought into the cutting room, even though we will have circled takes, everything is what we call “printed” or transferred.

HULLFISH: You mentioned watching four hours of dailies. How much dailies were you getting in? I’ve heard of people getting ten, twelve hours of dailies, and then what do you do? How do you watch that?

SHROPSHIRE: I don’t have an exact number on a particular day, but there was a lot coming in. There were days, obviously, when first and second unit was shooting simultaneously. It’s a lot to watch. And so, often my first watch would be only first unit because ultimately that was where I felt that they needed feedback from me.

I also had to evaluate how long any particular unit was going to be at a location. So if I knew — for instance — that first unit was going to be only at this location for a certain amount of time, and usually second unit was following right behind them, that was my focus.

Sometimes second unit knew they were gonna be in some place for a couple of days, so I felt like I had a little bit of time where if I had something to say about it, that I could comment. But it really keeps you on your toes because it’s not just about the editing. I found myself being in a position where you’re having to make sure and communicate with the director that you see everything that you feel should be there and so it was one of those things where sometimes editing had to wait. Editing just had to wait until I could go through everything and make sure that everything was there.

HULLFISH: One of your responsibilities is to let the director know that you think you have everything you need, right?

SHROPSHIRE: Yeah. Especially when you’re first starting out, that confidence that you build from doing this as long as we’ve been doing it and being able to actually confidently make that call.

It’s a great call when you call and say, “Oh my God! You did a great day in that scene in that performance.” But the call you dread is when you have to let them know that you feel like something’s missing. And I hate it. It’s the one thing about my job that I don’t like — to have to make that call. But having said that, I’ve never regretted it. And ultimately — because there are directors I’ve worked with now multiple times — they know when I call that they need to pay attention.

HULLFISH: What kinds of things have you had to make that call about?

SHROPSHIRE: The first film that Gina and I did together was Love and Basketball. The script was amazing. Gina knocked the film out of the park, but at the very end – where Monica has asked Quincy to play a game for her heart – she’s trying to win him back and the first night they went out and they shot the game and they shot the game in a very kind of technical way.

When the dailies first started coming in, what I was seeing was the physics of the game itself, but what I was LOOKING for — to some degree — was the intimacy of the game and what would create that urgency of: “I’ve got to win this. I’ve got to somehow connect with him in a way that maybe he’ll think twice about letting me go.”

When I started to go through the dailies I felt a little bit emotionally distant. I certainly had shots of when Monica was supposed to shoot or miss and when Quincy was supposed to shoot or miss, but the desperation I missed a little bit.

I put the scene together and I talked to Gina about the things that I felt we still needed to just “stick the landing” in those moments. She heard me.

When you go back and watch the scene: it’s when she starts struggling to get the ball from him and he’s kind of pushing her away and a couple of the looks that they had with one another.

So we did a little bit of storyboarding of looking at the scene that we had and looking at those moments that we could capture that would just cure it a little bit better. And so the second night they went out I actually went out that night and just kind of stood quietly behind and just watched and just had a few exchanges with Gina in terms of what they were shooting and we got what we needed.

It was challenging because she still was shooting. I couldn’t easily bring her into the cutting room and ask her to look at it. Gina is not a director that likes to see cut footage while she’s shooting. Traditionally she doesn’t necessarily like to do it.

Generally, what she’ll say is that she has something that’s in her head a certain way, so when she sees cut footage — especially during the production process — it isn’t necessarily helpful to her unless I make her watch it because either I feel like she needs it to inform her of something that I feel that she needs to be aware of.

HULLFISH: Especially with a scene that’s that critical to the movie. But that’s a harder conversation to have with a director than: “I need a close-up.”

SHROPSHIRE: Yeah. It’s hard too, because if you haven’t worked with the director before — and this was our first time together — there’s that added anxiety, but at the end of the day you’re both advocating for the film. You’ve got to put your ego aside. You got to put all that aside because at the end of the day it’s not going to — as we know — miraculously appear.

Sometimes it’s something as subtle as a performance. If you start seeing a performance skewing a certain way. You need to be able to communicate that to a director, and that can be daunting too because obviously they’re perhaps very invested in an actor’s performance.

At the same time, if you’re starting to see an actor do something — maybe it’s a particular physical thing or a way that they’re carrying themselves that starts to feel maybe a little bit too exaggerated — because you’re looking at the film as a big picture while they’re out there shooting scenes out of order and having to kind of track what a character is doing.

Those types of conversations — you just have to really pay attention to what’s going on so that if you see something that you feel maybe will become problematic — that we’re not going to be able to course-correct easily — and that’s why you have to look at everything.

If you’re seeing something that an actor is doing that’s maybe a little repetitive, you have to call those out.

HULLFISH: Those are difficult discussions to have.

So many editors have talked about the fact that the editing room has to be a safe place for the director. In my interview with Herve Schneid, ACE, he called directors “fragile creatures.”

What do you do politically — on a human, social-interaction basis — to know that you’re seeing something that’s very important to this director that’s very difficult maybe for them to discuss and you have to have these hard conversations with them?

SHROPSHIRE: What I really try to do is: before I make that call or have that conversation — is to really – as an editor – make sure that I’m looking at all the options. That I’m not jumping-the-gun. That I’m not creating a fire where there isn’t one, right?

I hate drama. I am the most anti-drama editors — not counting the drama in the scenes on the screen — so I make sure that I understand what the intention is or what I think the intention is. And then I approach it from that perspective.

I will first say, “I’ve been watching dailies or I’ve been looking at a certain performance and I just want to check with you because this is what I’m seeing and if that’s what you’re looking for maybe there’s something I’m not aware of.”

I have the script and I have whatever discussions we’ve had prior to shooting the film — and those things always change as we evolve and you go into production. So I try to approach it saying that I may be wrong or I may be seeing something that I’m just not privy to what the intention is. And so then within that, we start having a conversation.

If they feel they’re good then I feel like we’re good. I was on a particular film where I wasn’t on location with the director and dailies started coming in and there was something I was noticing in one of the performances — because this character is supposed to be somebody who is “on the spectrum.” (autistic to some degree)

I started to see this physicality in the actor’s performance. I was a little concerned that maybe it would become too caricaturish, but at the same time, I felt like I needed to say something. If I see a take where I don’t have it, then I think, “Okay, maybe I don’t need to worry.”

I was supposed to be going to the visit location for about a week anyway, so prior to heading out there I did put in a call to the director and I said, “There are a couple of things I want to show you. I have a couple of concerns that I want you to take a look at.” So when I went up I had cut together some scenes so that she could see what I was concerned about and it was something that she did decide to address.

HULLFISH: I think one of the things that helps in those instances is the relationship you’ve built prior. The director knows that you have their best interest at heart. They know that you just care about the story and making it better you’re not trying to call out a mistake or anything like that. As long as they feel that you’re an advocate for them, those conversations are going to go better, right?

SHROPSHIRE: Absolutely. Absolutely. I think that it is a matter of trust that’s built prior, but even if it’s a director that you’ve never worked with before you have to be able to speak your truth, and know that hopefully it’s received well and in the spirit of understanding that you are the film’s ultimate advocate. If it’s not, then ultimately they’re going to have to face what you’re saying, or find a solution — if there IS a solution to be found — at some point.

HULLFISH: Did you deliver your editor’s cut exactly to script?

SHROPSHIRE: That’s a great question. I would say… (smiles) no.

I would say for the most part, yes. Most of it was as scripted because ultimately I know that the director has that particular vision in mind.

I always feel that with the first assembly it gives me that opportunity to say, “I know what you wanted. YOU know what you wanted, but while I was playing around here in the cutting room, I found this really cool other way that we might want to look at it.”

Sometimes I may not put those cool things in the first cut. I’ll have it in a bin separately. I’m sure you have. Other editors probably say the same thing, but then I also kind of use the first assembly as a way to say well what if this. I always have to be judicious — making sure that it’s not something that’s going to completely take them out of the first viewing, but the director has enough — as does the editor — anxiety going on anyway, finally watching their first cut.

I say: “every director is their own force of nature” and they all have different ways in which they process that first experience. Some do it better than others. For some, it’s just fraught with all kinds of stress and everything.

I find that with the first assembly — depending on if I know the director and know that they’re gonna be cool with me showing them something different — I may move a scene around.

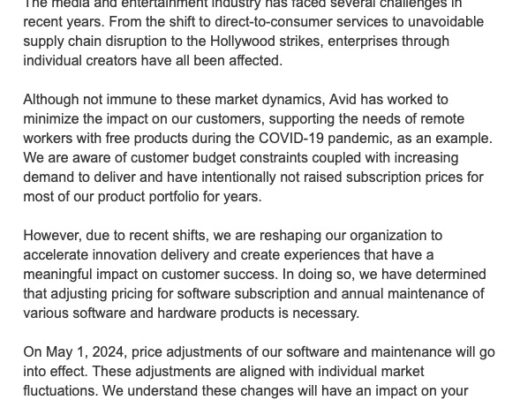

In the case of The Old Guard, we went through a number of different scenarios was, for instance, when Nile and Andy are outside the church talking during the abduction of Joe and Nicky. The question was how we were going to introduce the team coming in to take them. Whether it was going to be a sense of discovery? Whether we were going to introduce them to the audience first? How were we going to build that sense of impending dread?

That was something that I think I played around with a little bit before she came in. I also played with the dreams with respect to the order in which — and the language in which — the Old Guard dreamt of Nile and Nile dreamt of the Old Guard, so there was a little bit of work there.

With Gina, there’s always a discussion of music. Sometimes when I am putting together a first cut, I’ll talk to the director and ask, How do you feel about hearing music on your first cut? Because some people don’t want to hear it and Gina is somebody who actually really likes to hear music. She’s a very musically driven type of director.

In respect to that, my first assembly is something that allows her to explore some ideas of things that maybe I want her to hear.

But structurally, it was pretty true to form. There was a little bit more material with respect to the past of who the Old Guard was — just because it was material that was shot and that was stuff that Gina needed to see.

We talked ahead of time about how much of that she’d want to use, but I felt that she needed to see everything built in such a way that she could evaluate. Of course, those things shifted as we started to get into the director’s cut process.

HULLFISH: That church scene that you’re talking about brings up an interesting idea. I didn’t really think too much about it when I watched the movie itself — which is to your credit, of course, because it was unnoticeable — but it makes me think that when you have these intercut things — like a bunch of people who are waiting to be attacked and then an impending attack force — when do you decide: THIS is when we’re going to introduce the fact that they’re in danger?

A lot of people might just think it’s scripted. Well, it’s scripted that they show up at some point, but when?

SHROPSHIRE: Exactly. Especially in that situation because where they were staying, they were literally in the flight pattern for Charles de Gaulle airport, so there are planes that are constantly going by and this is part of what their safe house is.

This is a real town, by the way, in France Goussainville is not something that we made up. It was a small, sleepy town in France and when they built Charles de Gaulle it turned into this ghost town because it was in the flight pattern of the airport.

Credit: Netflix ©2020

Part of it was that you have these warriors in this safe house. Meanwhile, there’s a military maneuver that is happening right outside of their door and how do we create something where people are going to believe that these warriors who’ve been together for thousands of years would not be aware of what’s going on and whether or not to show the military unit approaching.

Should we allow Nile and Andy to have this conversation and then suddenly they hear an explosion? Or do you suggest that they’re coming in? We tried a lot of different versions. What would realistically create enough tension and urgency about what was about to go down without it feeling like “what are we waiting for?”

In fact, we had a little bit of fun with it later in the film and we actually had someone say “what the hell are they waiting for?” But it was something that we just kind of played around with and just tried different versions of showing them first, not showing them first, actually showing what happens to Joe and Nicky and actually showing….

HULLFISH: That was shot? That is not in the movie the way it’s airing, of course.

SHROPSHIRE: Yeah. It was shot. It was shot where you saw the bad guys going in and actually carrying them out. So there was a lot to play with there. And ultimately we felt that — in terms of staying with Andy, staying with Nile, having them take us through the aftermath of seeing what happens to Booker because ultimately you find out something about Booker that you’re not quite expecting. So

We also tried to make sure that we were creating a path where people wouldn’t wonder, “Wait a second! How did that happen?” So what we ended up with was a little bit of both. We used the actual part of the abduction as his memory to communicate to them through his perspective — or through the perspective he wanted them to know — which later you find out is actually something a little bit different.

HULLFISH: Jumping backward a little bit, when you’re gonna show a director that editors cut and you have changed something from the script, do you preface it in any way? “Hey, there are a couple of things I changed or this one scene I flipped?”

SHROPSHIRE: I try to say as little as possible as far as disclaimers, other than I may say something like, “I did try some music things through the course of it just in dwelling in the possibility of what if.” That’s my mantra: dwell in the what-if.

There are times when I will say something like, “You may see a couple of things in a different order than you may remember, but I thought this was an opportunity for you just to kind of look at that.” I really try not to get too specific and just let them kind of take it in and hopefully it won’t throw them, because I really don’t want to have those “Hey! Wait a minute! Where is that scene?” moment and then it has to take them a minute to get back in. You really don’t want to do that. I try to mention things that I feel like might throw them if they’re not aware that I’ve done something there.

It’s all about timing. Generally, you are so ahead of them by the time they come in in terms of you having lived with the material and built the material and you know the things that at least your mind you want to really talk about or remove or adjust and you have to be able to be patient and let them have the process that you had.

They have to kind of catch up to you a little bit and you have to give them that time. And sometimes if you try to suggest something too early when they’re not ready to hear that yet, it’s not helpful to the film. But it’s all about timing and when you bring those forth — those ideas.

HULLFISH: Talk to me a little bit about the action scenes. What’s your process with an action scene? Do you create selects reels? What do you do?

SHROPSHIRE: Basically, I do my usual dailies process and then it depends on what the scene is. Sometimes I will use my multi-cam and I will literally start building a sequence and I’ll start literally just editing through multi-cam. I’ll start to create a select reel of different angles based on multi-cam as a simple foundation.

The other thing that I often have to do — especially for a fight scene or something where they’re doing multiple movements or a piece of choreography keeping the camera going where just go back and reset instead of starting a new take over and over again — now I’m using that sequence and starting to pull the ones that I feel physically are working for me.

In those cases — especially when it has to do with the stunt coordinator or it has to do with a second unit situation — I will look at the notes. I’ll look at the script supervisor’s comments, whether it’s from the director of the second unit director.

For instance, Danny Hernandez, who is the fight coordinator on the film – If he had certain movements — a martial arts move or something — where he commented that takes 4 and 6 were really great and accurate movement on this particular choreography, I obviously kept those as selects and was always kind of referring back. But then once you build the scene, those things often change.

I build my selects of movement and choreography. If it’s a particularly long scene where they’ve broken it down into “phase one” “phase two” “phase 3” I usually like to try to get the entire scene down even in its most fundamental place. I like to be able to just build the scene. If you look at my timeline, it’s seemingly pretty messy but I build layers of the same action on top of each other so that I can sometimes just go through and look at the different movements back to back. Sometimes it works sometimes it doesn’t -depending on what the thing is.

There are times when you look at my timeline and I’ve got four or five, six video layers of the same thing.

I’m old-school in the sense that I call them work bins. I’ll have a work bin for a particular action sequence and that will include my early cuts. It’ll include things I just built. Or maybe it’s just a movement that I really like and I want to keep it.

I start very broad and then I just start to kind of narrow it down and I try not to get myself too caught up in the minutia, especially during production because I just need to know that I have everything I need. Because even within a particular sequence, if I know that second unit is following behind first unit to grab things that Gina’s requested that they didn’t get and that she knew that second unit could grab for her. That was my opportunity to ask, “And can you get this? And what about this?”

I don’t like to use the word “rough.” Everybody uses the word “rough.” I say, “Editors don’t do anything rough!” So that’s kind of how I do it.

We always talk about action as this kind of big daunting thing to overcome, whereas I find that it’s a different set of tools and of course it’s challenging but I found myself. Infinitely more challenged sometimes by those quiet moments and the scenes that people would not necessarily consider difficult.

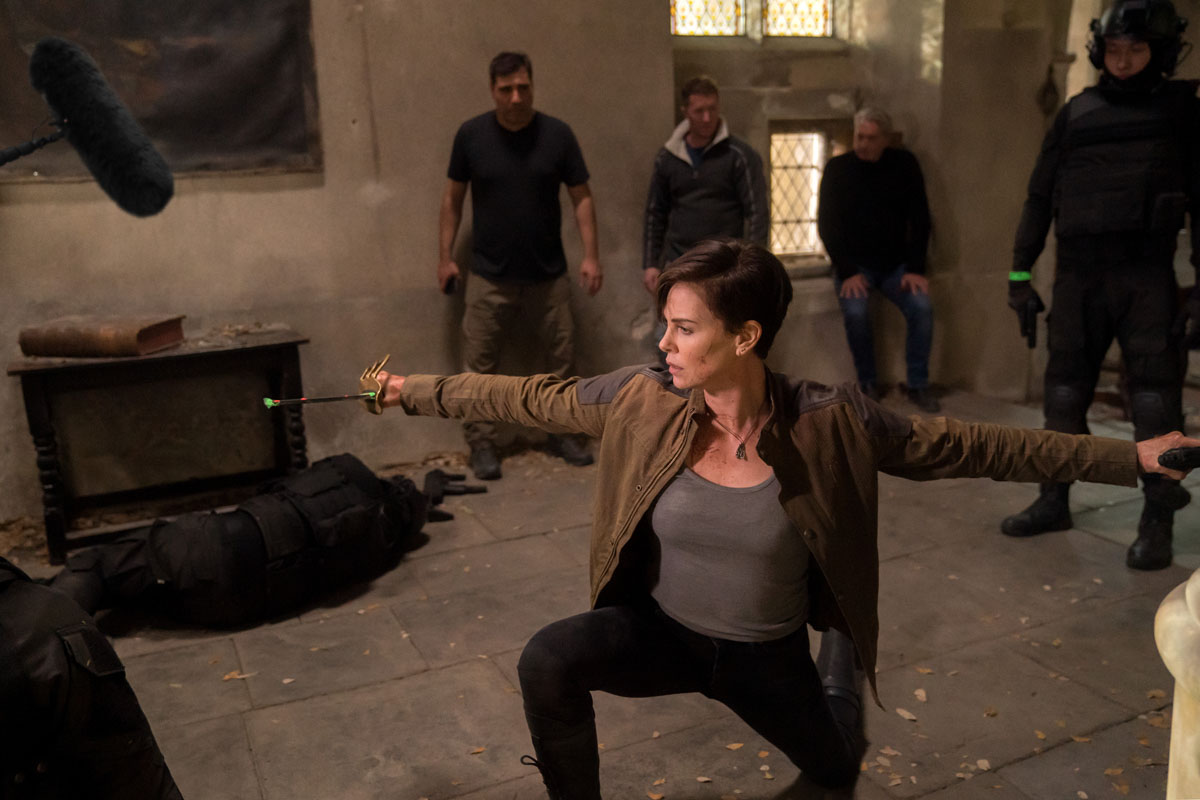

But it was a fun one with the action scenes because they also had to speak to tone on this movie because there were so many moments where you had characters talking about the existential part of mortality or being mortal or killing. So when you got into the fight scenes you wanted them to have a certain degree of energy but also to remind us that we were in this graphic novel and to allow yourself to have fun with it and let it be bad-ass.

Photo Credit: AIMEE SPINKS/NETFLIX ©2020

So it was very important — depending on what action scene it was — that we were also carrying a certain tone. A good example is the one where Andy has to go and fight in the church and she leaves Booker and she leaves Nile to go take these guys out because she knows that she’s got to get Nicky and Joe back.

So even the choice and music — the choice of allowing that scene to be kind of this dark, edgy, but ultimately — I hate to use the word “fun” — but this thing where you kind of see who Andy really is in her efficiency of movement.

We could have put on the standard action score cue to put her through that, but when I first started putting together the scene, to me it had such an arc to it that I just loved the idea of it being operatic in a sense. That’s how it felt to me — the way that it had been choreographed and the way that she was moving. It was like watching her do this very, very efficiently laser-focused dance and I didn’t want it to take itself too seriously.

Ultimately when I presented that to Gina it wasn’t with the song cue that we currently have in, which is called “This Is the World We Made.” I love the vibe of what that means. It’s this woman who ultimately doesn’t really like to kill, but she’s very good at it. If she needs to, she’s very efficient with it and she’s fighting a world that has been made around her.

So that wasn’t the first song that I put in for my first assembly, but mine was kind of equally operatic in that sense of the scene and allowing the tone to have a little bit of dark humor to it to some degree.

Photo credit: Aimee Spinks/NETFLIX ©2020

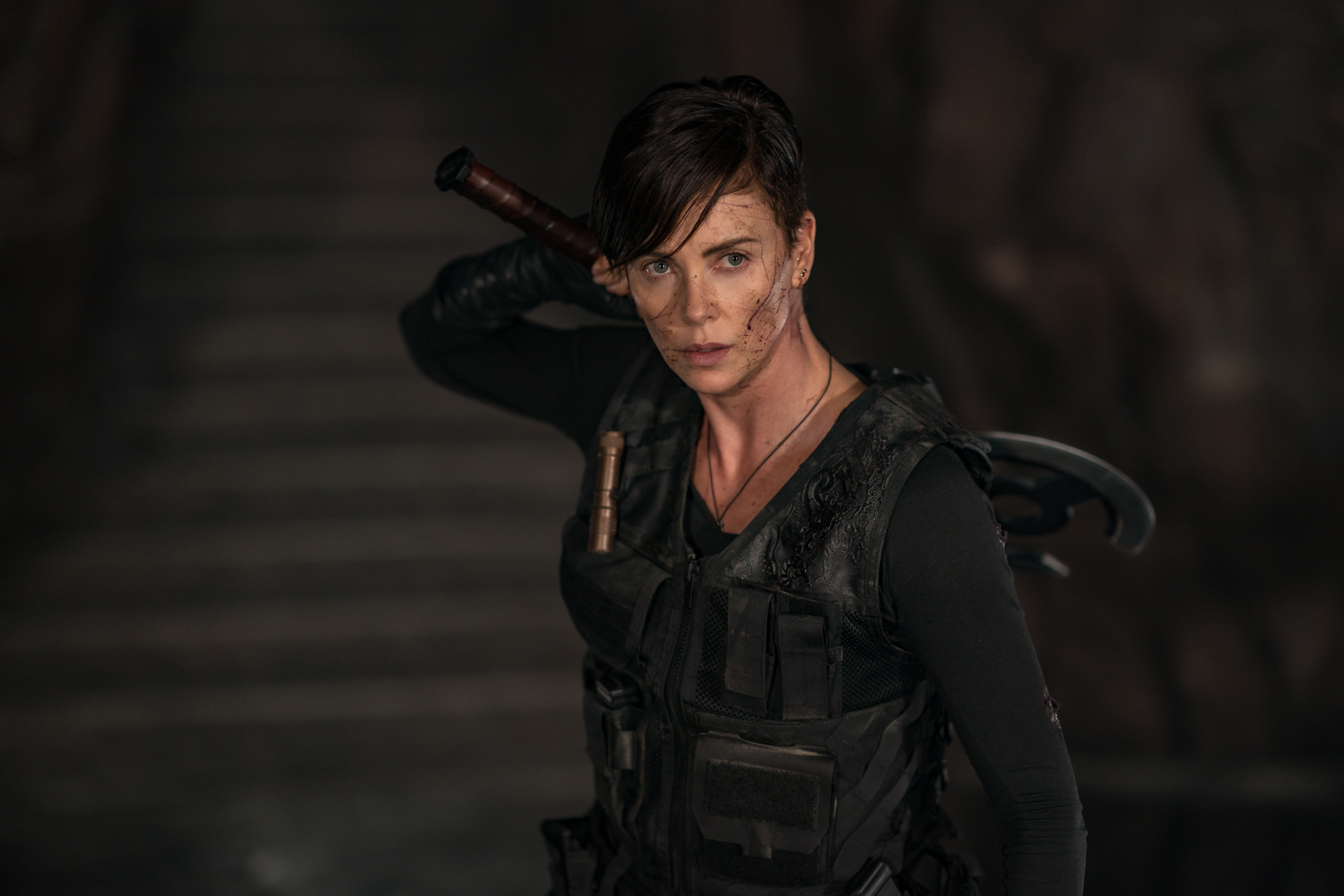

HULLFISH: While we’re talking about music in that scene and the scene that leads up to that, we were talking about when do you show that there’s an approaching force. Talk to me about choosing the music so that the music is not either giving you that kind of horror movie vibe like, Uh-oh! Here come the bad guys! You don’t want that to happen probably. What did you do?

SHROPSHIRE: I’m really someone who likes discovery and that includes how you approach music and movies. It’s very funny because there are times when I work with composers — and we have amazing composers with Dustin O’Halloran and Volker Bertelsmann on this film — but I find sometimes that composers like to jump the gun a little bit. They kind of like to come in a little earlier than where I’m hearing the music.

So — not with this film, but it’s happened before — when you’re finally having a composer spotting the film and the first music starts to come in and you’re watching the scene and suddenly you start to hear music. Often, it’s too soon for me. They’re not allowing the audience to have that moment of discovery. You’re trying to manipulate them a little too early. I hate it when I’m in a movie and the music is trying to tell me how to feel.

Part of that is really choosing that moment for me where the audience can be a little bit ahead of you. I think audiences like to be a little bit ahead. They are always kind of searching for that and I don’t like leading the audience through a movie — or at least them being aware of it. And so musically, it really is about finding that space between not coming in too soon where you’re jumping it and then not coming in like right at that moment where it feels like you’re pushing my button.

Photo Credit: AIMEE SPINKS/NETFLIX ©2020

There is this kind of in-between space that I think you find and hopefully you become aware of the music without becoming aware of the music.

What I loved about our conversations with the composer and our music editor. Often the music arrives from the composer and it’s not exactly in that space. That’s why having a great music editor allows you to play around with what you feel like you’re hearing and then they can go back and communicate that to the composers and they can have that discussion.

We were very lucky on this film to get the composers in earlier than we ever have on any film. And I think that that was to Gino’s credit that you know those discussions were had very early and Netflix was very open to having us have them involved very early.

Like when the explosion happens at the church and you have that little moment of silence before you start to let something come in. With the song actually in the church It just fits so beautifully. We put that song on and I don’t remember making any adjustments. It felt like the composer and I had some kind of weird Vulcan mind-meld or something because we got that song on there and it was just amazing.

HULLFISH: I’m sorry to jump backward this far, but is prepping your dailies just laying stuff out in a bin or are they doing a KEM roll.

SHROPSHIRE: If it’s just kind of a typical day they will usually just put them all together in a KEM-roll type of situation where I can just press play and not have to load it. I like being able to sit and just watch it as one long piece.

In one of the scenes, the assassins were wearing these headcams and so we had so much headcam footage come in. In that case, I said, “Look, Corinne, I need your help here because it’s just way too much stuff to look through.” So she built me these sequences of that stuff.

When it came to comps (VFX pre-vis/temp VFX) I really threw that stuff to Corinne and talked to her about what I wanted to see. Even just comping the monitors.

But generally, with dailies, I just love to play it through. It’s hard because you have to decide if you’re watching a multi-cam section, do you watch each of those cameras separately? That’s why I prefer watching dailies in multi-camera. I prefer watching ABC cameras at the same time just because I know that I’ve seen everything — especially if I’m having to try to move quickly. Then I’ll go back and watch specifically the close-ups again or a particular camera again that I know that I may be using.

A lot of times, with multiple cameras, if they’re shooting these wide shots and you know that you’re going to use those very judiciously, it becomes less important to me to focus on that camera, because I got a sense of what that camera is. I can always go back and look at that. It’s really as we start getting into the detail of a performance or detail of a close-up or medium shots or anything like that. Then I’ll go back and focus on that particular camera.

I want to watch everything, but I also know that they shot this wide shot so many times. I’ve got with that is.

HULLFISH: This is one of those movies that I love the structure of it. You’re jumped into the middle of a situation. You don’t even understand it. You don’t know who the people are. Nothing is explained to you. We don’t start off with a big montage that says: Many years ago there were these immortals and now here they are! We don’t get any of that.

When you started seeing scenes in context — instead of how you built them when you were cutting during dailies — did you see scenes where you thought: “It would be interesting to cut to this guy’s reaction at this point because maybe later that’ll mean something to people?”

SHROPSHIRE: It’s actually the reverse of that. The look is there and you want to highlight that particular look because — yes, you’re right — later on, you will understand and you may not remember that look until you see it the second time. It will have a different meaning the second time you watch it and who doesn’t love that when you watch movies?

The thing that I feel was the best experience I had very early on The Old Guard was when Gina sent me the script. She said I want you to read this. She didn’t tell me anything about it. She just said: “read the script” and I knew nothing about the graphic novel. The script was different from what it is now. In fact some of the beginning was very similar to the graphic novel. But that kind of changed just through the evolution of getting to production.

But I remember reading the script and getting to the “kill floor.” And when these people started coming back to life I was like, “What is this?” It was one of those moments where you kind of know that unless somebody is living on a desert island and suddenly a TV is dropped onto the island with The Old Guard playing, they’re never going to have that experience the way that I had it.

Ultimately, because of marketing, the audience is going to know that they were going to be immortals. But having said that, there was very deliberate discussion about how we discovered who they are. I kept saying as I built this movie, “Nile is us. We are Nile.”

In other words Nile — being the character that is coming into the world of the Old Guard — we’re going to learn about them the way that she learns about them. And even in the graphic novel you kind of first meet the Old Guard, then you meet Nile.

There was a little bit more of this kind of parallel thing that was happening between the Old Guard and Nile in the graphic novel that within the course of making the film it made more sense for you to get to know who the Old Guard was first. You get a sense of where they are in the world. They’ve been double-crossed, especially Andy’s character. And then Nile comes in.

So with respect to building things and creating that sense of discovery we ultimately decided that starting at the beginning of a film where you’re in some kind of period of who they were back in the Crusades or back in sometime early on with Andy was not going to give you a sense of who this person is as we drop you into their world.

There are moments where you just want to get to know them as people — as a team — as an efficient mercenary team who are really good at what they do, and then, through that, you also start to get little hints of their humanity or maybe why they are who they are.

Something as early as the “kill floor” when they start to regenerate, and there’s a moment where they kind of check-in with one another and there’s certain things within two characters checking in with one another that — the first time you see it — it may seem like they’re just looking at each other, but after you see the film, you realize that these characters have a certain relationship that you discover as the film goes on.

So those kinds of hints were always really cool to have. Knowing that in some ways the relationship between Andy and Booker is something that becomes very integral as the film goes on and understanding where they are in their lives and why they are who they are and the loss that they had in their lives. That is again discovered through conversations with Nile. She really allows us to see the vulnerability and humanity of who these people are.

It was always the intention to have those things that you can go back and watch the film again and maybe look at differently.

When Nile first comes into the Old Guard, she constantly asks “why?” “Why us?” She talks to Andy about killing and: “Is this supposed to me?” There are a lot of conversations where I think you really get to learn the humanity of who they are. And she ultimately is the first person who really does see the why and that’s what makes her decide that this is a path she’s going to take because she is the reluctant new immortal who doesn’t really understand why she’s been put in this position and doesn’t accept it, which is something that was really important for Gina.

Gina wasn’t looking to have a character that would just automatically accept her fate — that she was a strong woman in her own right as a Marine who is thrust into this world that she doesn’t understand, and she wasn’t going to just easily accept what was happening to her because she was her own warrior.

HULLFISH: What concrete examples can you give or what can you say about how your vision that “Nile is us and we are Nile” informed your editing?

SHROPSHIRE: Making sure that within the point-of-view — and sometimes that term is used loosely — but in terms of how you are sharing information or giving and who is receiving information in any given scene.

If you look at something like the dinner table scene, for instance, there’s a lot of back-and-forths. That scene starts very quietly. Nile is looking at the Old Guard and the Old Guard is kind of sizing her up. She’s the first person to ask the question, “So are you good guys or bad guys?” And the response is, “It depends on the century.”

Then you start to allow her to hear who they feel they are as the Old Guard. Meanwhile, you have her taking that information in and you have Andy watching her and Andy doesn’t initially say much at the beginning of the conversation and then she kind of then comes to the table sits down and they then start having more of a discussion and you start to learn more about Andy in some ways in terms of her humanity. I think it’s the first time when she’s really talking about the past in such a way that it feels a little more vulnerable. She’s talked about the past as being angry and frustrated and she certainly wasn’t looking forward to Nile’s entry, but she knew it was something she had to do.

But it’s the first time when you really start to kind of get a sense of who they are and you’re learning that through Nile, and how she is taking in that information and how we’re seeing how she reacts to what they’re telling her.

HULLFISH: So in scenes that you had her in, that was consciously in your brain that this is the POV that I’m looking for?

SHROPSHIRE: For Nile, when she finally hears the stories of their history it freaks her out, and it makes her angry and she leaves. We wanted to make sure that we weren’t romanticizing this idea of being immortal. You can consider it a superpower, but there is a curse to it.

Nile says, “I don’t want any of this.” By the time she’s saying that to Andy you understand as an audience why she doesn’t want any of it — why she can’t accept that this is part of what her life is.

She’s not ready to let go of the people that she loves or any of it. It seems very dark and scary to her. And I think that part of being able to allow your audience to see both sides — or all sides — of who the Old Guard is is through how Nile takes that information in more than anybody because she’s the most human or the newest of them as we would be.

HULLFISH: Anything else you want to talk about.

SHROPSHIRE: I’m always fascinated by what fascinates you. You’ve seen so many movies and talked with so many editors. I was listening to your podcasts with Simon Smith and it was like an hour and forty-five minutes.

I love when the questions are asked that I can start to think about the answers.

HULLFISH: You had great answers. I loved a lot of that discussion — especially the last question that we talked about is SO about editing. How do you make the audience care? How does this not just be an action film with a bunch of kicks and punches and gunfire? And then you’re done with it and you don’t care. That’s what makes it interesting and enjoyable.

SHROPSHIRE: That’s the thing that’s been great about the film because Gina was very deliberate in the type of film she wanted to make. When she went into Skydance to get this film, they said, We’re bringing you in because we love what you’ve done with your movies as far as your characters and Love and Basketball and Beyond the Lights. They wanted her to be able to bring her sensibility to this genre.

Gina’s intention was always to make an action drama film and I think people that have embraced the film have really gotten what her intention was and I really appreciate that she did something different. We took the time to allow our characters to express and have silent moments and have contemplative moments.

We love to point out the one on the elevator with Nile and that we let her go up all 15 floors, whereas in any other action film she would have gone stepped into the elevator and then stepped out of the elevator.

Obviously, I love action movies. It was nice to be in a position where we could do something different and the people that have loved it, have loved it for why it’s different. I think there are still people that went in thinking they were just going to get a straight kind of Atomic Blonde John Wick-type of balls-out action film, but that was never our intention.

We wanted to do something different. I’m really happy with the way the film turned out. It’s those kinds of moments that I love when I see a film. I love the Peter Parker and the Bruce Wayne and the Clark Kent and the moments where you get to see the people who become these incredible action heroes. There’s something about that alter ego of theirs that are the moments that I love and I feel that The Old Guard is a great introduction to the characters so that wherever they go — and if there’s a sequel — that we’ve planted you in who they are and where their humanity is, and now they can go anywhere and people will love them hopefully because we gave you that opportunity to get to know them a little differently.

HULLFISH: Yeah. One of the ways that I think of when you mentioned getting to know them a little differently is Andy’s character. I loved at the beginning that scene where she eats the….

SHROPSHIRE: Baklava?

HULLFISH: Baklava! And she’s describing all the ingredients perfectly and it’s just great. Before you see her kick butt, right? There’s no action up to that point, correct?

SHROPSHIRE: No.

HULLFISH: So you haven’t seen anything of this woman. You can kind of tell she’s a bad-ass, but the first thing you basically see her do is eat some baklava and tell you what the ingredients are. I’m thinking, “Is this an episode of “Good Eats?” What is this?”

It’s a wonderful way to meet her character and to care about her. She appreciates the good things in life down to the small things in life.

SHROPSHIRE: Yeah. And she’s been around long enough and had enough baklava to know where they come from. That’s part of it too. That’s what’s so great about the Old Guard is that there is a conceit to immortality. And yet at the same time, they do have mortality. So there’s that weird kind of dynamic between, “No. They can’t die. But yeah they kind of sort of can. They just don’t know.” They could die from a paper cut just like we don’t know what our time is.

It’s funny because I feel like now there’s a certain conceit that some of us are living with respect to COVID where there is this disease out there, and yeah I can get it, but I’m not going to wear a mask because I really feel like I and there’s so much similarity to this. But yet this little virus can take you down, right? And so in some ways within our own self-immortality or perception thereof, so the Old Guard is very similar.

I love the fact that they can move through their lives in a certain level of conceit but yet still be incredibly vulnerable and be human.

HULLFISH: I love that about this movie. I have some clips. Can you talk about these?

Audio Player Audio Player Audio Player Audio PlayerHULLFISH: Thank you for editing this movie and thank you for talking with me.

SHROPSHIRE: Thank you for inviting me to your party. When you asked me to do this, I thought, “I made it to Steve’s podcast!”

And to celebrate the diversity and largely female post crew on this film, I provide the post credits, so you don’t have to try to pause Netflix to give them their props!

Post Crew:

Post Crew:

Editor Terilyn A. Shropshire, ACE

1st Assistant Editor Corinne Villa

2nd Assistant Editor Angela Latimer

2nd Assistant Editor (UK) Danielle El Hendi

Music Editor Jen Monnar

Temp MX Editor Del Spiva*

Visual FX Editor Sean Villa*

Visual FX Assistant Ethan Henerey*

Post Production Supervisor Ruth Hasty

Post Production Supervisor UK Tania Blunden

Post Production Coordinator UK Rachael Havercroft

Post Production Assistant Alana Feldman

Post Production Assistant UK Annamaria Pennazzi

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Instagram and Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now