In this episode, I’m talking with editor Joe Matoske, ACE, executive producer, Beverly Chase and post-production supervisor Arthur Randell.

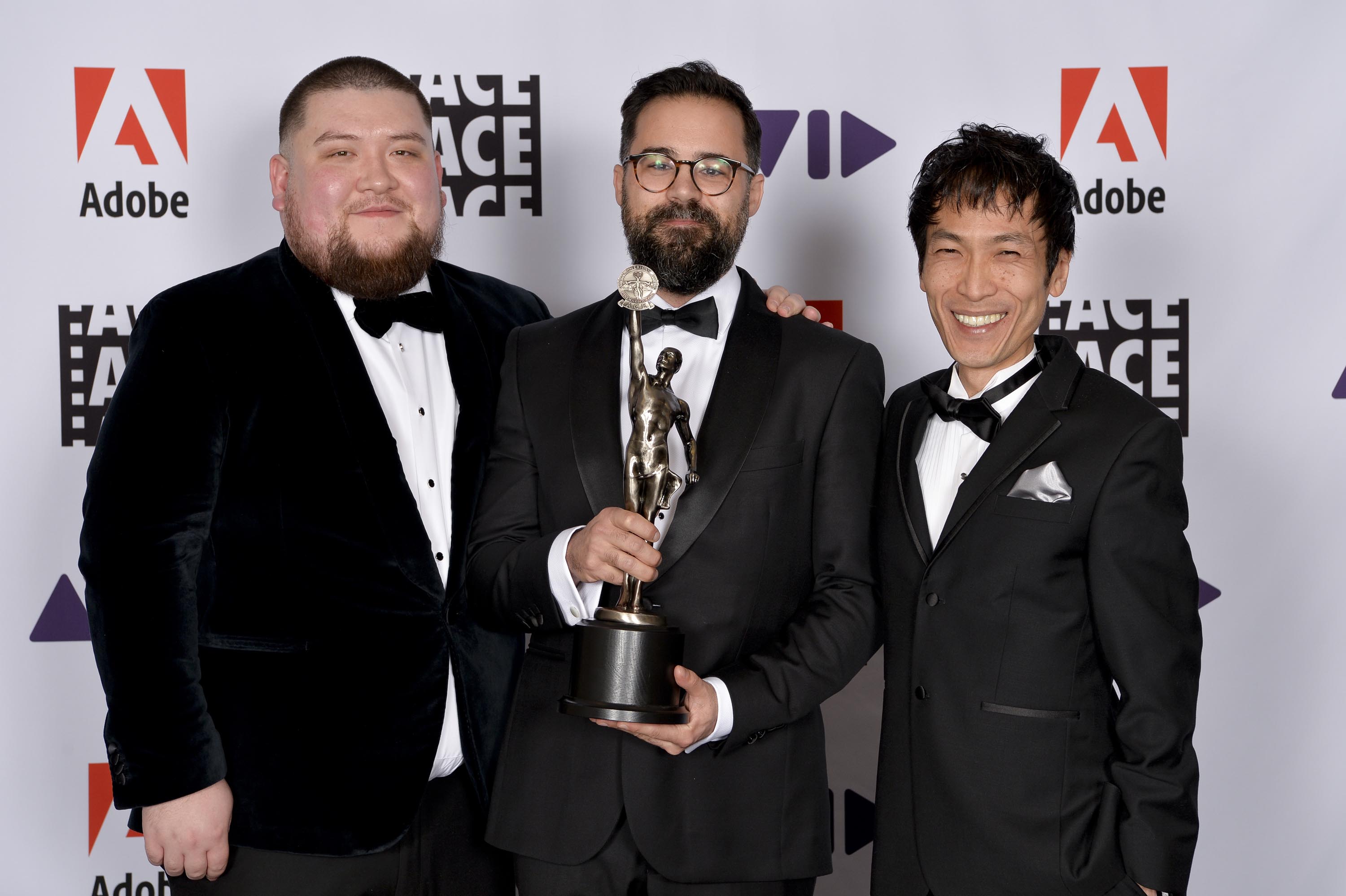

They are part of the team that worked on Vice Investigates: Amazon on Fire which won the ACE Eddie for Best Edited Non-scripted Series. The other editors who won for working on the film were Cameron Dennis, Kelly Kendrick, and Ryo Ikegami.

This interview is available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: Could each one of you introduce yourself? Ladies first.

CHASE: My name is Beverly Chase. Everyone calls me Bev. I’m currently the executive producer and showrunner of Vice on Showtime and prior to that I was the co-executive producer of Vice Investigates on Hulu. Prior to that I was an editor forever.

MATOSKE: I’m Joe Matoske and I’ve been an editor at Vice for about four years now.

RANDELL: My name is Arthur Randell. I’m the post-supervisor for the long-form content that Vice News produces. That included the HULU series and this Showtime series that I’m working with them on.

HULLFISH: It’s very nice to meet all of you. Congratulations to Joe and the team on the ACE Eddie. That’s exciting.

MATOSKE: Thank you so much.

HULLFISH: Let’s just get started on the structure of the story. How was the structure of the story determined?

MATOSKE: It was a two-week edit and the field team was still producing while the edit was going on. We had four editors Cameron Dennis, Kelly Kendrick, Ryo Ikegami and myself. Cameron Dennis would take the large parts of it and sort of divvy out scenes.

He would meet with a small team of people every morning and they would look at the structure as new footage was coming in and they would assign it to each editor. Then we would pass it back to him and he would work it back into the master — the full edit.

HULLFISH: So it sounds like you worked in “pods” or scenes, right? Can you explain what some of those scenes might have been for somebody that was watching and doesn’t see a scene?

MATOSKE: A great example was the rodeo scene, cut by Kelly Kendrick, which was a lot of people’s favorite moment in the episode. He took all the rodeo footage, cut it into a scene and showed it to some of the producers who were working on it.

We had Craig Thompson, Ruben Davis, and Lee Doyle — who were sort of working within the edits and they would all give him notes and then he would pass it back to Cameron who would put it into the larger piece and then Cameron would send the full cut to Beverley and to (Exec Producer) Subrata De and to Craig and they would do notes on the entire thing.

Then Cameron would pass that back to Kelly to address notes before putting it back.

HULLFISH: Bev, tell me a little bit about producing something like this and trying to organize multiple editors. Was there a paper cut or did they just get footage and they start working?

CHASE: That’s the beauty of the way that we do things. We don’t paper cut anything — at least on our long-form side. We basically leave it to the editors. And in this case, it was four of our most talented guys on this. It’s a big trust exercise.

So we basically have them build out their pods and find the story within the edit. Once it’s all sewn together is when we realize where the holes are — what we need to plug in — in terms of adding voice over to make things make more sense or adding additional sound to streamline the story. It’s all sort of born and birthed out of the edit rooms.

HULLFISH: When you get those pods or scenes back from the editors do you think, “Here’s this rodeo scene, but let’s split it up and go back and forth between it and the U.N. story?” Have them intercut. What’s the thought process?

CHASE: We don’t typically intercut our scenes. Occasionally we’ll do an ending chorus-of-voices but for the most part, we keep our scenes intact as scenes and that’s what I think makes them feel immersive and cohesive. You’re basically living in one scene at a time.

HULLFISH: How are you juggling the time aspect of individual elements of the overall story? Which story gets more time? Which story gets cut down?

CHASE: With this particular doc, I feel like we didn’t really fight a time issue. We had just the right amount of material. When you see it all together you can make a judgment call pacing-wise what’s dragging or what needs to be extended or what’s not clear. To be honest, the story drives all that. We just wanted everything to breathe and feel really good.

MATOSKE: There was one scene that I cut that had probably the most fat of any of the scenes — which was the raid. They spent about a day-and-a-half shooting everything that we had for that raid scene. I was only cutting my specific scenes, so I wasn’t paying attention to the full context of the doc. So my raid scene started off about five minutes long, then the producers would tell me that they were moving the raid scene to a particular spot in the doc, so we needed to cut 30 seconds out.

For the most part, there were never any big cuts. It was more about going through and tightening up. There was a weird amount of not having to kill your darlings in this doc.

HULLFISH: When you saw the stories in context, were changes made inside of stories because of the way they related to the other stories?

MATOSKE: Yeah definitely. That was Cameron’s job. I would cut the scene however I saw fit and I would give it to him and he would make the changes based on what was coming before it and what was coming after it.

There are a few moments where there are really clean hooks between scenes — so when the rancher looks at the photo of what his land was before he bought it, and then that goes right into him present-day on his land.

Similarly, when the journalist is telling Seb Walker where not to go, and then it cuts to Seb Walker in the military truck going to that place, those are all places where Cameron Dennis took the scenes and built the bridges between them.

HULLFISH: I heard you say they shot everything they needed for the one scene you did in a day and a half. What was the amount of footage in a day and a half that you were receiving?

MATOSKE: For that raid, in particular, it was probably about six or seven hours of footage that I just whittled down. That scene was done by a producer that I had worked with several times. We had a good relationship. Obviously, because he was there producing it and sending it right away, he couldn’t tell me what to expect out of it.

So it was just about whittling down from there. I got it down to an hour of what I thought the core moments were, and then crafting that into probably about a four-minute scene.

HULLFISH: So seven hours of footage down to a four-minute scene?

MATOSKE: Yeah.

HULLFISH: And you’re not able to speak into what they’re shooting, I’m assuming?

MATOSKE: Yeah, which is true in most cases but especially this one. There was no weighing in before or after they shot a beat.

First of all, they had terrible internet, so it was hard to even be in connection with them while they were shooting.

HULLFISH: And Beverly what were the organizing principles of determining the order of those stories? What helped you guide that?

CHASE: As far as the story structure, we basically left that to the senior producers on the team — Ruben Davis and Craig Thompson — and they took the first crack at the structure because they were in constant communication with the teams as they were shooting in the field.

Then we would do a screening. I think there was only one big screening where I made a structural change and that was to start at the U.N.

I feel like that wasn’t part of the original game plan. Is that right, Joe?

MATOSKE: Yeah, that’s right. We were so in-the-weeds that being able to show it to Bev, who then was able like to look at it with fresh eyes, she could see things clearer.

HULLFISH: Were there stories that you guys worked on that were discarded?

MATOSKE: Not a ton. Vice News, in general, is a well-oiled machine and I don’t think the producers really shoot a lot of unnecessary beats. I think there were only about two scenes that didn’t make it in.

We shot two rodeo scenes and that was done just in case something didn’t work out in one of the rodeos. It was just because it was so hard to get access to them. But the rodeo with Seb at it worked out great. Then there were one or two additional scenes where the military was warning people about the fires and not to go near them that we cut because we had everything we needed. We didn’t need the extra time in there. Those are really the only things I can think of that largely didn’t make it into this story.

HULLFISH: Did the second rodeo scene even get edited together?

MATOSKE: Kelly cut both versions. He found that the one with Seb was stronger for a variety of reasons. So the ending is a revisit of all of these ideas. It’s sort of a chorus of everything we had already heard.

So I used visuals from the unused rodeo in the ending just because we didn’t want to repeat any shots.

HULLFISH: What was the team like that put this whole thing together? We heard a little bit about the editors. Who else was involved in something like this?

CHASE: It was a total rockstar team we had going. It was made up mostly of Vice News Tonight’s climate team. They were running it, but the producers on it were Juanita Ceballos, Adam Desiderio, Lee Doyle, Daniel Vergara, and Agnes Walton and Seb Walker was the correspondent.

Those two teams were separated in the field. We had a couple of field producers, local producers, and an AP. And then wrangling all of that media was Arthur, who was behind-the-scenes making it all happen.

We were being extremely ambitious in terms of shooting this in 4K because were shooting the fires in Brazil and the challenge was that this was a crash” so we needed to figure out how to get this 4K footage back to Brooklyn to cut it while they were still in the field, and that was a pretty Herculean effort.

HULLFISH: Arthur let’s talk about that. What was the solution? I heard that there were some interesting workflow ideas to be able to get this to work so I would love to hear from you.

RANDELL: There were a couple of challenges. It was a really large team and that’s what we really needed to make it happen. It was a very fast turnaround. It was kind of a hybrid team. Some of the team members were part of our short-form daily news show and some of them were a part of our long-form team.

I had already worked with the long-form team setting up the workflows for the Hulu show from the beginning. That show was the first show that Vice News had shot and mastered in 4K, so we’d gone through a bit of a crash course in how to do that with the first couple of episodes.

But I think the real challenge with “Amazon” was that not only were we turning it around incredibly fast but that the team would be needing to deliver media from the middle of the jungle.

We had a proxy workflow for working in-house so essentially it was relatively easy because we just had the teams make the proxies for us in location so that just took a little bit of training the team in how to do that in the field. But once they were able to get those proxies converted and back to base then it just slipped into what we’d already been doing with all of our episodes.

So there was a lot of media and it was definitely really hard to get that from the locations that the teams were in, but once it is in, it never got in the way of the editors working — which is the most important thing.

HULLFISH: The cameramen were probably doing the transcoding of proxies?

RANDELL: I originally asked for some DITs to go with the teams just to take the pressure off the camera teams, but for a variety of reasons it just didn’t work out.

One of the beauties of the way Vice works with the teams when they’re out in the field is that they’re very mobile. They can go to locations and pivot when they need to, and I think that that’s one of the reasons why they’re able to capture the things they do, so I totally get the reason for not sending a DIT, and I did have my misgivings, but the shoot teams really aced it. They were able to absolutely send what we needed to get back to base.

HULLFISH: What were you guys editing in NLE-wise?

CHASE: We’re all Premiere.

HULLFISH: And what were the proxies that the field teams were generating? How did you determine what they were gonna be, and why was that choice made?

RANDELL: That’s a really good question. One of the interesting things about working at Vice is that the capture is usually a variety of sources. It’ll be MXF, MOV, MP4. It’s a real variety so we did have to come up with a one-size-fits-all codec. For this, we ended up going with ProRes Proxy .mov.

That is not THAT light. It still produces some pretty heavy files, but I set that as the minimum. I think the edit teams do need to be able to edit with something that represents an image that is close to what the final product will be. Also, it maintains all of the audio channels with the original raw.

One of the things that was really important is that we needed to be able to flip it very, very quickly and go into online, so whatever the solution was, it couldn’t slow down the back end.

HULLFISH: What was the schedule between when the first crew went out and when you delivered the show through online?

CHASE: I think it was three weeks total for everything — from first shoot date to master. It was pretty insane.

MATOSKE: I think Agnes and Seb did their first shoot around the first of October and our lock date was October 20-something.

HULLFISH: That’s incredible. Another quick, geeky question for Arthur is: what was the workflow? You had somebody delivering proxies from the Amazon jungle through the Internet. What was collecting all of this? What hardware or what organization were you using to get footage from a Dropbox account? How was that working from some laptop in the Amazon to Joe sitting in an edit suite?

RANDELL: Most of the time it was via Aspera. Because of the large team that was a staggered approach to the shoot. So at very key points, they were able to send raw footage back — either with the correspondent or because a team got cycled out.

So there were a few times when we could have really lost a lot of time by waiting for proxies, we were able to get like a jolt of raw footage that we just processed back at base and that made it a lot quicker.

There’d be periods of times where they were just out in the middle of nowhere and they just didn’t have the internet to be able to file. So another really clever part of the way that it was produced was obviously designing points in the shoot where they could be back at base at a major city where they could file.

So it came in dribs and drabs but it always seemed to be just enough footage to keep the project going.

HULLFISH: Joe, I’ve got a question for you — though you might not have edited this since there were multiple editors — there was a moment that I loved in the cold open. During a hard question from the host, there was a reaction shot of the interviewee as he swallows hard. Like, “I didn’t want to have to answer this.”

Talk to me about using cutaways and how it’s not about just information but it’s about human reaction and emotion.

MATOSKE: So the cold open was cut by Ryo. Ryo, Cameron and I all have worked on Vice News Tonight since it first launched. Part of what made our edit style work so quickly for “Amazon” was that we were all sort of used to the same style — used to the same sort of rhythm of editing. Do it fast. Trust one another.

One of the things that I know I picked up from Vice News Tonight — that I have no doubt Ryo shares — is that it’s very important to be fair to everybody who we’re cutting interviews with. So, for me personally any reaction shot I use from somebody in an interview has to come from that moment.

If I needed a cutaway and it happened to be while a camera was shaking or the person was mid-sneeze or yawn or something, I might consider swapping it in for a very neutral shot, but I’m gonna assume the swallowing shot of the interviewee was probably an authentic moment.

HULLFISH: That’s interesting. An interesting point is perhaps the difference between a type of documentary crew that is more news-oriented and is really trying for the journalistic truth compared to — there are many documentaries where you’re trying to make a statement and you’d be happy to use that shot of the guy swallowing from some other moment in the interview.

MATOSKE: I think that carries through with certainly how I think about sound design. The sound effects that we’re using in our pieces all come from the scene that I’m working within.

Same thing with reactions. You want it to be as authentic as you can.

CHASE: I’m very, very sensitive — being an editor myself. As an EP, when I’m screening these things, these guys can attest that I’m extremely sensitive to any sort of a cheated cutaway or any kind of a reverse shot that doesn’t seem like it’s accurate.

FluidMorphs or Morph Cuts would never get past me in a million years.

HULLFISH: I think I could slide one past.

MATOSKE: We also don’t use Warp stabilizers on anything. It’s a bit of a gray space. If it was a B-roll shot of something very neutral then maybe. But we don’t use Warp stabilizers on anything that’s like verite with character interview. Which is why sometimes we end up stuck with showing a shaky camera at a really key moment.

HULLFISH: That’s kind of an interesting point that I’ve run into throughout my career working different places: different people and different companies have different rules: like no FluidMorph. No stabilization. What are some of those things that if someone came onto your team they would have to learn and be aware of?

CHASE: Such a good question.

CHASE: I don’t know if I have rules, but maybe pet peeves.

I don’t like it when my editors break up voice-over to insert “nats” (a short piece of natural sound) in the middle of sentences. I’m very sensitive to the natural cadence of speakers and if you intentionally break up somebody’s sentence, it’s very jarring to a viewer, in my opinion.

So I’ll often talk to my editors about not breaking up voice-over or track just to insert those “nats.” and I think that you can very easily and organically insert the “nats” in those particular breaths without breaking up the cadence of the way someone’s naturally speaking. So that’s kind of a rule.

HULLFISH: The reason why it’s interesting to me is that — especially if somebody is an aspiring editor or an editor that has only worked one place — when you go to someplace else, you might not realize that not everybody does it the way you do it and that each location — Vice or some HBO doc series or Oprah — they all have different ideas about what’s acceptable, what’s not acceptable and what they like and what they don’t like.

MATOSKE: One of the really nice things about editing at Vice is there are very few hard rules, which is why I think there are so many editors who have their own style and Vice supports that and gives the editors a lot of creative freedom in telling a story, however they learned how to edit.

But probably the thing I’ve learned the most from Vice News Tonight — which is sort of a rule I take with me — is B-roll is as intentional as anything else that you’re editing, so don’t just cover an interview for the sake of covering it. Don’t be afraid to just let an interview play out. If you’re going to do cutaways of something that’s not the interview make sure it’s as deliberate as the interview itself.

HULLFISH: Talk to me a little about the speed of editing. When you said you had a day-and-a-half shoot with seven hours of footage and a two-minute final cut, how long did you have to assemble that and what are some of the things that you do to be able to edit that quickly?

MATOSKE: The first thing is watching everything down as quickly as you can. Once I’ve watched all seven hours down — and obviously a lot of that is verite footage, so there’s a lot of nothing going on — so just sort of double-timing my way through it just so I have a map of it in my head.

From there it’s just like you’re whittling. Once I’ve whittled something down to like twenty-five minutes that’s when it feels like I have something that I can work with and mold and do whatever I’m going to do with it.

HULLFISH: I just talked to another editor about documentary editing and he said the advice he was given when he started was, “You’ve got 100 hours of footage. Your first job is to get it to 50. And then your second job’s to get it to 25.”

CHASE: For me, it always comes in this end process where part of the end process of this whole film was we had such a tiny bit of time to wrap this up, so the last day — on a weekend — each act was still broken up into the different rooms, so I would go into each room, one at a time, and do a fine notes pass sort of on-the-fly and then run to another room. Then, while that person was addressing notes, I would go to the next room and was just went around kind of round-robin.

In those notes, if we’re watching an interview and I feel like somebody is about to say something — it’s sort of a feeling where: “I bet if he just finishes the sentence there’s going to be something more there” and we’ll just matchback and you kind of uncover these nuggets.

I trust all of our editors to pull the best stuff because they’re so good at what they do. There’s always gonna be stuff you can mine for that you may have missed the first time around, but you usually don’t uncover that stuff until you’re trying to address a note.

I’ll wish they said X, Y, Z, and — sure enough — if you matchback and unroll what you just were editing, it’s there. So it’s kind of instinctual I think to go back and find those missing nuggets.

HULLFISH: Are you guys working too fast to get transcripts done?

MATOSKE: Yes. Very few things were sent out for transcription.

CHASE: But we had it all translated because a lot of it was not in English. So in having those translations done you automatically have transcripts for a lot of it.

RANDELL: Yeah, we wouldn’t have “Trinted” anything in English. But even for a lot of the speakers with thick accents, like Macron, they don’t get great results from auto-transcription software, but we would have “Trinted” it and we would have passed it along to the production team. Sometimes if there’s time, they’ll clean it up but those transcriptions — and even the translations — I don’t think the producers are fine-cutting based on those. That’s just really to be able to send back to the team in the field as well as the team in the office to give them an idea of what’s there.

HULLFISH: How are you dealing with the translations if you don’t speak Spanish?

CHASE: Translation workflow is a way to produce edit-ready subtitles in Premiere. Anything that we would get sent out for translation we would do with a series of string-outs of the scene requiring translation. We would send files out to the translators. They would send an XML back and when we converted that XML back into Premiere those subtitles are ready-to-air subtitles, and that obviously makes that whole back-end process a lot quicker.

HULLFISH: So as an editor, you’re seeing the translation on the screen so you don’t have to be able to understand what they’re saying because you’re actually reading it?

MATOSKE: Yes. That’s correct. Because of the way our subtitles are formatted, the text that goes inside the subtitle is technically the name of the clip, so you can actually command-F and search for words and it can jump you through your timeline.

So if you want to find somebody talking about “rodeo” you can just search and it’ll show you every instance where somebody — in Portuguese — says rodeo.

HULLFISH: Portuguese, not Spanish.

CHASE: Right. Also, it makes it easy when you’re scrubbing through material and you can’t watch it in real-time or even double time. If you go edit by edit, as you’re tapping thorugh, you’re just basically reading their words faster than you would hear them.

MATOSKE: You asked, “How do you watch everything down and know you don’t miss a moment?” I just remembered that there was a great instance of that.

I was the first editor who took a pass at editing the rancher segment and I made an impulse decision to make him light-hearted and have some funny moments with him in there — because I knew he was going somewhere in the middle and I felt like everyone sort of needed a breather because so much of this story is very tense.

So I found the moments of Seb trying on the big wide-brimmed hat and joking about the pants and we tested that out. I think it was Bev who gave the note about letting that be part of his character — these funny moments. That’s when Cameron and I were able to quickly talk and Cameron found the moments with the rancher picking up his dog at the gas station.

Those were moments that I saw the first time that I thought was funny, but I didn’t think had a home in this story. But it was only when we were fine-cutting when we found all of the moments with the dog and brought them into the edit.

HULLFISH: That’s one of those tricks about editing. A lot of times when you’re watching it in a first pass — because you know nothing about the story — you don’t know what’s valuable and what’s not and you could say I don’t need this. But when you get it in context then you see how you could use a shot of a dog getting picked up at a gas station.

MATOSKE: When I cut the moment with the wide-brimmed hat, I didn’t think there was any way it was gonna make it through the final cut, but part of editing is that you just try things and you see what sticks. And I never thought that that would lead to the whole build-out of his character. It’s all about these human, slightly funny moments.

HULLFISH: How were you organizing? Or is there an organizational principle other than just the story? How else do you organize material especially if you think another editor is going to take it over for you? I would think that’s even harder.

MATOSKE: Yeah definitely. I think all of us working together on the same project for three years helped a lot. I think Arthur can probably speak to the organization process of all the media.

RANDELL: There’s a really rigorous system in place that all of our AEs adhere to precisely because of the reason that you’re saying. We have a number of editors working on projects and at any moment they could be switched from one to the other or — like in this case — maybe we have to add multiple editors to work on the project and for that reason the way that the project’s organized needs to be consistent.

The AEs will take the footage notes that we get back from the shooters and they’ll create a group of sequences per day and then a group of sequences per scene and then even sometimes break that scene down into different footage types like verite, b-roll, interview, and everything’s labeled like that so essentially the editor can open and see right away all of the beats throughout that day.

In the way that we work — in the way that the editors tend to attack the material — being able to have that overview of everything in the day in a really digestible format helps them dive in and really attack the footage as quickly as possible.

HULLFISH: So using a selects reel instead of a bin or is it a little both?

RANDELL: No footage bins. Just sequences. We call them sequence breakdowns. It’s a series of sequences. The more that you can be specific with those sequences the better for the editor but it really depends. Like a verite scene can be quite complicated to organize so there’s a lot of work that goes into making that as clear for the editors as possible.

They just get a bin of sequences based on the day’s beats.

HULLFISH: And then when you use those selects breakdowns to cut a scene are you using Premiere’s pancake timeline capability?

MATOSKE: I love the pancake style. I have one whole monitor that I just use for my timeline and so the top timeline is whatever sequence I’m scrubbing through and then the timeline below that will be my work timeline and I’ll just be dragging clips and dropping them as I go.

HULLFISH: Do you do any audience screenings or just producer screenings?

CHASE: No. For all the Vice investigates it’s just me and the executive producer Subrata De. We’re pretty much the last and only eyes on it once it gets through the production team.

HULLFISH: What are some of the types of notes that might be generated from one of those screenings?

CHASE: I’ve been told my notes are very thorough by other editors. Because I’m an editor there’s a lot of edit notes in my notes. I think another executive producer wouldn’t really give the same types of detailed notes that I give. I’m very timecode-specific on my notes and I also like to provide solutions to the notes instead of just being vague and just saying “this is working.” I always try to come up with some sort of solution so that I know that my notes can be executed.

HULLFISH: Joe, do you just love her?

MATOSKE: I do. Working with somebody who has an edit background can be risky, right? I’ve worked with senior producers who come from edit backgrounds who essentially just want you to be their hands: “use this music cue at this timecode” and Bev doesn’t do that.

Her notes are very relatable but she won’t tell you to change the music. She’ll say, “I think the tone of the scene can be this” or something. She doesn’t step on your toes. She leaves you to figure it out. But her notes are: “I know what you’re going through right now.”.

HULLFISH: Can you think of any specific notes that she would give you other than the tone of a piece of music?

MATOSKE: I had built the whole ending of “Fires” out and I think some of the notes on that were: how much of that final interview did we want to show the person talking versus did we want to revisit everything we had seen in the fires? Initially, I had used a lot of the on-camera of the person we were interviewing and I think Bev’s note was to stay in this moment of revisiting the fires and don’t worry about going back to their face because we’re on our way out the door anyway.

CHASE: I think I had the most detailed notes on this in terms of the cold open. Ryo did a brilliant job cutting it in his first crack but because we had only done a few other Vice Investigates, it was a very particular sort of style that I was going for that cold open.

I felt that in addition to having it hook people in immediately, it needed to also tell a story. So he had all the best moments together to make that cold open, but that doesn’t necessarily create a narrative. So I ended up scripting out a little bit of it so that the narrative was clear. Then Ryo did this brilliant job of covering that and making it really cinematic. But I think pulling a narrative out of that open was one of the biggest challenges.

HULLFISH: Where are you guys getting music from? Do you have composers at all? Arthur, do you have a big library of music that’s on some big server that everyone has access to? And are sound effects the same way? Or are you guys strictly limited to the sound effects from the story?

We also have music supervisors on the show and pretty much every time we launch a new show, they’ll pull a bin of thousands of tracks for the guys that’ll kind of match a brief that they think the show should be based around.

They’re usually using the theme music which they’re usually heavily involved in as well, so that’s really helpful. Especially for us in Vice News now we’ve got a couple of really big bins that have represented each of the shows we’ve worked on. We can go out and do more bespoke stuff. We did think about using composers for each of our episodes, but I’ll let her speak to the decision behind whether to use a composer or not.

CHASE: Part of what we were trying to do before we started making the series was using an emerging artist to score each one of the hours. As the delivery times kind of shrunk on us we ended up having to use our music supervision team, but they’re incredible at pulling things.

A lot of our editors will just pull their own music or just request music from the libraries and then we end up trying to clean them afterward. We have a lot of composers that we work with to score things. Sometimes we’ll do sound-alikes for music that our editors fell in love with it that we couldn’t license.

That’s one of the strengths of Vice, in general, is the relationships that we have with different bands and we’re able to sort of get really cool music to work with and not just JIngle Punks.

MATOSKE: I’m very specific. I’m very film-reference-oriented. Often what I’ll do is as soon as I’ve watched the footage down, I’ll reach out to a music supervisor and I’ll send them examples. Like, “I really love the soundtrack from Cartel Land (2015 A&E documentary).” Or I might ask for the percussion of Mad Max. Oftentimes it’s actually horror films. I love referencing horror films because those scores are very building and very low tension. So I’ll use a lot of stuff like that.

They’ll send something to me, and if it’s not quite working we’ll just use that as a reference point to get us to where we want to go with it. But they’re great. It’s very rare that we have to pull music more than two or three times for a scene.

HULLFISH: What do you think it was about this show that made it EDDIE-worthy?

CHASE: (Bev starts to look through her computer files) I wanted to see if we talked about the tight schedule in our essay submission for the EDDIEs, because I think what I found most remarkable about it is the fact that these four guys turned this around in the amount of time they around it around.

It looks like something that was edited over the span of a year. Honestly, it looks like a six month to two-year documentary. And I think it’s the brilliant scene work that they did in every single one of the scenes. It’s that they were brilliantly edited, but also that they were brilliantly edited in ten days just kind of blows my mind as an editor.

I’ve “crashed” many things myself, and just the level of detail that was in each and every scene was what I think put it over the edge.

HULLFISH: My jaw hit the floor when I heard you say two weeks or three. I mean either one of those numbers. Anything under six months is insane.

RANDELL: The thing that blew me away was that it seemed really crafted and even though it was cut by four different editors, there’s a real consistency to it. Not only wouldn’t you know that it’s been done in two weeks, but you wouldn’t know it’s been done by four editors. I think it’s really seamless and I think that that’s a real testament to how well the guys worked together.

HULLFISH: Did you have any access to the new Premiere shared projects or how were you getting that much media and that many editors working together in a Premiere project?

RANDELL: I don’t think this would have been incredibly difficult 12 months ago, but ever since Premiere came to the table and let you open two projects at the same time, that’s pretty much a game-changer in terms of sharing projects.

Before this, the Vice News Tonight team had a very rigorous approach to sharing projects. It was based around naming conventions and locking audio and video tracks. We experimented with Premiere’s project-sharing functions but it never really worked for the fast turnaround, large group of editors that we had working on the show.

It was enough for us that we could open two projects at the same time and just copy and paste. Pancake editing is also a game-changer and allowed something like this to run a lot smoother.

MATOSKE: When we were at the EDDIEs, the thing that most people were talking about was the speed in which we turned it out. The other time Vice has won an ACE EDDIE was when they made Charlottesville, which was even faster. That was a 30-minute show in 72 hours. It’s about how crafted something can be in such a short amount of time.

HULLFISH: When you are looking at your fellow editors and the other people that were nominated or other people that you have decided were nominee-worthy, what are you looking at? What makes a piece strike you as worthy of award or worthy of nomination?

HULLFISH: Bev, what about you? I see a bunch of awards on your shelf behind you. What is something — when you look at someone else’s work — that makes you feel that is something that is worthy of an award or a nomination?

CHASE: I am such an editor fan girl.

To me it’s all about feeling. If an edit can make me feel feeling, I think that’s a testament to great editing, especially in documentaries. When you’re letting things breathe and getting out at the right times and caring about every single shot.

One of my film professors in college — we were analyzing Psycho shot by shot. It was a great class. We spent the entire semester watching Psycho. What we learned in that class was that every single frame — top to bottom — every single frame of a clip matters. So when I’m giving notes on a cut or watching a cut or super-impressed by a cut that someone else is doing, it’s because I can tell that they’re caring about the in and the out of every single shot that they’re putting down in the timeline. Every single thing is deliberate. Every moment. Every blink. Every breath. Every beat that you hold a sentence till the last possible moment. Those are all things I think that go into actually caring about what you’re making and having it have an impact on the person watching it.

HULLFISH: I just want to thank you all for being with me. Thank you for being on Art of the Cut.

CHASE: Thank you so much for having us. This was so fun.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.