In this interview, I’m talking with Hervé Schneid, ACE. We’re discussing his editing of the eight-episode Amazon Prime TV series ZeroZeroZero.

Hervé has received numerous awards and nominations internationally including being nominated for a Golden Reel from the Motion Picture Sound Editors for his work on the feature Neruda. He has cut more than 70 films including Day of the Falcon, The Very Long Engagement, and Amelie, which had been nominated for 5 Oscars.

This interview is available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: You’ve been editing long enough that you had to have started cutting with film. When did you switch to some kind of NLE?

SCHNEID: I’m an old school guy so it’s been quite a while that I’ve been around, so I did start with film of course. Starting with reverse film. (Film recorded and developed as “positive” instead of a “negative” printed to positive)

I started with 35mil as an assistant. That was in Israel a long time ago and then I came back to France and I started to look for work, but that was just impossible at the time because you had to have a professional card and in order to get one, you had to have done film school, which I hadn’t done, so I couldn’t find a job in the feature film industry, so I started to do TV and that’s where I used reverse film and doing TV. Also, video cameras came in then I finally could work in the film industry.

It took a few years but I could do it. And I started to do commercials. The first Avid came to Paris and I was there when they opened the box and I was the first one to put my hands on it. So of course I used a technician to help me because it was really something completely different. I cut the first commercial on the Avid in Paris.

HULLFISH: What year was that? Avid was introduced in 1988 at NAB. I started cutting on Avid in 92.

SCHNEID: It seems it was before. 90 or 91. The first feature I cut with Avid was The Tango Lesson and that was in 1996 and 1997. It was tough at the beginning. You master it. You love it. I wouldn’t — for nothing — go back to film. When I look at the films I’ve cut in 35 mil, I just wonder how it was possible.

HULLFISH: If you had had to cut a film in 35 and a film on Avid that the style of editing or that the choices you would make would be different?

HULLFISH: If you had had to cut a film in 35 and a film on Avid that the style of editing or that the choices you would make would be different?

SCHNEID: I’m not sure, because I tend to apply — to the digital way of cutting — the way I had developed with film. So I always try to think before doing.

HULLFISH: That’s a crazy idea!

SCHNEID: Yeah. Some people think it’s great. Apple-Z has done a lot of bad things to editing, but it’s very good if you master it in the right way. But if you just DO without thinking about the consequences, then you just do for doing, which is not the right way to do it.

I try to think first and then, of course, apple-Z is very convenient to change your cuts or your direction, but it shouldn’t be used so you can do “whatever.” I try not to do “whatever.”.

HULLFISH: I completely respect that approach.

Let’s talk a little bit about ZEROZEROZERO. Can you tell me how you got involved in this show?

SCHNEID: I received a phone call from the director, Stefano Sollima. He had called me about a year before to cut Soldado.

HULLFISH: The follow-up to Sicario.

SCHNEID: Yes. It was really exciting. I loved the script and the guy really attracts me very much. So I said “yes,” but I was in the middle of a very big personal turmoil, so I had to say “no.” I had to do to call Stefano and tell him “I’m sorry. My wife is starting to shoot her first feature film as a director. I’m producing it and it’s going to be in Kazakhstan. So I can’t let her go by herself. So I’m sorry I have to choose love and go with her.”

He said, “OK,” and I was sure I would never hear anything from him anymore. When you say “no” to a director, then usually you’re not called again.

But a year later he called me to cut ZEROZEROZERO, so I couldn’t say no. The script was great, and the guy is terrific. Plus, I went for a year in Rome to do that, so that was the cherry on the cake.

HULLFISH: So the editing was done in Rome? It’s a big international production.

SCHNEID: Yeah. I started in Paris for two months and then we moved everything to Rome.

HULLFISH: I love the slow burn of the opening of that first episode. It takes its time. It lets it reveal itself to you. It doesn’t make sure the audience knows everything.

SCHNEID: Yeah. Stefano is really someone special. He is really a master. He’s a great director and he knows what he’s doing, and it’s very reassuring when you are facing such a big amount of rushes. I had a lot of material. They were shooting as if for an American blockbuster, really.

I had about 60 hours for each episode, so it’s a big ratio. He knows where he goes, so it’s very reassuring and very good.

HULLFISH: How can you see the director’s control over the material when you’re watching rushes?

SCHNEID: I didn’t know Stefano beforehand. I just had a few phone calls with him and we talked a little bit about the thing. But it transpires from the rushes. You see what he’s looking for. You see the difference in the takes as the takes go by. You see what has improved, what he’s looking for. You understand this. So you can deduct what he’s looking for.

HULLFISH: Did you read the book? I understand this is based on a book.

SCHNEID: I didn’t want to because it’s two different things. I’ve done a few films before which were adapted from books, and I didn’t want to read the books before. Because obviously it’s another thing.

The director takes the story and makes it his and you don’t want to be distracted by somebody else’s vision. You want the director’s vision. So I read the book afterward.

HULLFISH: Did Stefano say what had made him call you — what he’d watched of yours that he respected or liked?

SCHNEID: We’ve never talked a lot about this. He just respected my work.

HULLFISH: The cold open on this is 20 minutes long, which is pretty unusual, right?

SCHNEID: Yes. We asked ourselves a lot of questions about this long introduction before the main titles.

HULLFISH: The titles, I thought, came at a place that made a lot of sense but it was 20 minutes before you saw the titles. It was scripted that way?

SCHNEID: Yeah absolutely.

HULLFISH: You told me a little bit about the schedule. You did five episodes?

SCHNEID: At the beginning, it was planned that I cut all of them — all eight. I realized quite quickly that it was just going to be impossible. The scale of the series was much bigger than everything which was done before by Cattleya, which is a BIG production company. They have made a lot of series, but none of them were as bold as this one.

HULLFISH: Ambitious.

SCHNEID: Yeah, ambitious! Bold and cinematographic. So they shot a lot. It took a long time. At first, I was supposed to be the only editor and I just had one assistant. One editor and one assistant to deal with all this material was just impossible, so I quickly realized that it was going to be impossible for me. So I asked to have two assembly editors hired to help me go through all of these rushes.

We would discuss together and I gave directions and they just clean things for me and then I would take everything back and redo everything mainly and adapt it to my taste.

But then we saw that even like this it was impossible to reach the schedule, so I offered and Argentinian editor to come do director Pablo Trapero’s last three episodes because they had worked together before, so it seemed to be a very convenient solution, although a lot of the material of the last three episodes were cut already.

That’s what I found was complicated because this is my first series, so it’s a very big change compared to the way I work with a feature film. I find it very convenient, the different state of mind you have when you cut a film.

That’s what I found was complicated because this is my first series, so it’s a very big change compared to the way I work with a feature film. I find it very convenient, the different state of mind you have when you cut a film.

You receive the rushes and then you just look at the rushes. You make your first choice, a first assembly, and then when you have the big picture then you realize where are the problems and what can be arranged and shortened and everything. Then you go into the fine-cut process — first with the director and then the fine-cut.

At the same time, you do some sound and music. But you switch from climbing the mountain — having all these little rocks and then one by one you do your stuff.

But with a series, you have to do everything at the same time because you have rushes for an episode and then you’re fine-cutting another one and you’re editing the music for another episode and you’re doing sound for another one. So it’s just a mess. Your head just explodes. It’s really a very different exercise.

HULLFISH: In addition to picture cutting, you were also the music editor, which is a huge job as well.

SCHNEID: Yeah. That’s something I really love to do.

On this occasion, it was really perfect. I had this discussion with Stefano very early. He was asking me about who would I see as composers for this film, and I gave him a few names and one of them was Mogwai because it’s very dark, it’s very electronic, it’s very oppressive. It was one of HIS three choices, so it took five minutes to say, “OK, let’s go with Mogwai.”

On this occasion, it was really perfect. I had this discussion with Stefano very early. He was asking me about who would I see as composers for this film, and I gave him a few names and one of them was Mogwai because it’s very dark, it’s very electronic, it’s very oppressive. It was one of HIS three choices, so it took five minutes to say, “OK, let’s go with Mogwai.”

So I could work a little bit with existing themes from them, and I had worked with them on a previous film before on the film, “Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait.” It was an art film and I loved the music. It’s really it’s fantastic. I really loved it.

It was really good to cut the music because they’re not film composers. They’re a band that does incredible themes and they play it for hours and then you have to adapt them to the image. It’s a fantastic job. I love it.

HULLFISH: So you knew who was going to be the composer so it was easier to temp? Were you temping all with their stuff?

SCHNEID: Absolutely. We did two things: we chose a few existing themes with Stefano and very early we were in contact with them and they kept on sending pieces, and I would put them in and give them directions according to the scenes where they were supposed to go.

HULLFISH: My sense of the music was that it was not leading the audience in any way. A lot of music — it’s telling you, “You should fall in love with this girl!” or whatever it is.

SCHNEID: Sometimes you have to do it but it shouldn’t go with the picture. It should say something else — either the opposite or something connected to what’s happening but not in an obvious way, in order to be interesting, but it’s different each time.

HULLFISH: While we’re on the topic of sound and music, I notice that you also have a Golden Reel nomination for your sound editing. Talk to me about how your music editing — which you do on almost every film — and your sound editing informs your picture editing.

SCHNEID: I think sound is very very important. Music, of course, but sound is paramount to a film, and in all my cutting versions very early on I try to have good sound. Sound which is saying what’s happening because sometimes information doesn’t come through the image but through the sound and the complexity of the situation can be said with a specific sound at a specific moment.

So I really work a lot on the sound and I give a lot of very precise directions to the sound editors. I love to work with the same sound editors very often, whom I know and appreciate, and we know each other very well and we know exactly how to work. Very often, they’re working in the room next to mine, so I go to that room, or they come to my room. I show them the piece — what I think. They show me what they’re doing. It’s a big exchange.

HULLFISH: The sound editors are your choice to bring them onto the team?

SCHNEID: Yeah. It’s my team, but it’s never against the director’s opinion. But usually, directors don’t fight for a sound editor. They trust you. It’s never imposing. I’m just offering names.

HULLFISH: You know how you’re going to have to work with them. Editing the series with you doing the first five episodes is not very normal. Normally, it would be switching back and forth with each editor taking a separate episode. As you said, at first you were trying to cut the whole thing.

HULLFISH: You know how you’re going to have to work with them. Editing the series with you doing the first five episodes is not very normal. Normally, it would be switching back and forth with each editor taking a separate episode. As you said, at first you were trying to cut the whole thing.

SCHNEID: Yeah. They didn’t shoot in order. It was shot on five different continents. So depending on where they are for the shoot, you received material that goes into episodes one and five and six and two.

When the material comes, you cut it. But that’s at the beginning then very soon you are overwhelmed with the amount of material, so you go in order.

HULLFISH: Yeah. Was there any thought of breaking up the stories more than they were? Because they’re told in fairly big chunks — here’s Italy for 20 minutes and then here is America for 20 minutes and here’s Mexico for 20.

SCHNEID: Yeah that was a very strong decision. When you are in a place you don’t switch to another one. You don’t come back to a previous place in the same episode. It was a philosophy of the show. When you’re in Italy you stay in Italy and then you go to Mexico or America but you don’t come back to Italy in the same episode.

HULLFISH: In the very first episode there’s a little bit of non-linear storytelling. Can you talk about whether that was exactly as scripted or how were those time jumps handled?

SCHNEID: Well everything was written — but you know how it is — it’s written in a way and then when you get the material you do it the way it’s written and then it might work perfectly at times and sometimes it doesn’t really work as it was planned, so you find another way of doing it. But respecting the concept! Very often moving things around and maybe starting later or earlier. Adapting to the concept. But it was written and it was planned like this.

HULLFISH: How many languages do you speak?

SCHNEID: Not that many. French, English, Spanish, now a bit of Italian of course, because after a year in Rome it helps. And a bit of Hebrew and a very small amount of Russian.

(I should note that the clips I’m putting into this article seem to be from Spanish airings. Several languages are featured, but in the US, they are obviously subtitled in English. Most of the series is in English.)

HULLFISH: Does that knowledge of those languages help you as you’re editing in those languages, because the show is in Spanish and it’s in Italian, and it’s in English.

SCHNEID: Of course it helps, but I’ve cut a lot of things in languages I didn’t speak, so as long as you have a script in English or French or in the language you command, it’s OK. The repetition helps you quite a lot except when it’s in a very, very different language — like Chinese or Japanese. This is quite complicated because it’s not the same music. But if you follow the music of language which is not far away from yours then it’s no problem.

Of course, it takes a little bit longer and you have to have an assistant who speaks the language. You have to check with them that you’re not losing a syllable or that you haven’t cut in the middle, but as long as the music is good it’s no problem to understand the interpretation of the actor. You know if the delivery’s good or not, even if you don’t speak the language. You feel it.

HULLFISH: It’s so interesting that you’re talking about language as music because that’s what I always think about with the differences between languages — it’s the specific rhythms of French compared to American English or French compared to Italian or Spanish — the rhythmic quality of it.

SCHNEID: Sure, but everything is about rhythm. You know that!

HULLFISH: Yeah. The rhythms of language. Also, they say that if you’re a good singer you’re a better speaker of another language. Have you heard that?

HULLFISH: Yeah. The rhythms of language. Also, they say that if you’re a good singer you’re a better speaker of another language. Have you heard that?

SCHNEID: No, but having an ear obviously helps.

I have this story about ear and languages. A few years ago, I did a film called East/West. It was directed by Régis Wargnier who did Indochine — which received the Oscar for Best Foreign Feature Film a long time ago (1992).

East/West was a story set in the USSR and there was this amazing Russian actor Oleg Menshikov and he had a big part of his lines in French because he was married in the film to a French girl. So he had to speak French for quite long lines — really long lines — and he didn’t speak a word of French and he’s a very good musician, very good pianist — and he learned everything by ear. It was just amazing looking at the rushes. LONG takes with a lot of lines, and it was just perfect, perfect French. And he didn’t understand. I mean, he understood because he had the translation, but he didn’t know how to speak. It was just amazing. So ear and languages go together. That’s for sure.

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about the pacing of these scenes and how they might have changed once you saw things in context. Because it felt like almost some of the different countries had their own pace to them. The Italian is almost Godfather-esque, but then the Mexico scenes have a totally different energy to them.

SCHNEID: Yeah it’s a much much more frantic ambiance. Mexico I thought was an incredible place. It’s so cinematographic! Everywhere you put your camera, it’s beautiful. The people are great. It’s so much alive. It’s incredible. I love Spanish and I love Mexico.

I did a Mexican film a few years ago and I really enjoyed it so much. Although the theme was very tough and violent and everything, but it’s a great country. So of course the rhythm changes from one location to another because it’s not the same characters. The action is not the same. You adapt to what you show. It’s not you who adapt, it’s the film. The film gets its own life, its own rhythm. You just have to understand it and follow it. That’s the way I try to follow.

I did a Mexican film a few years ago and I really enjoyed it so much. Although the theme was very tough and violent and everything, but it’s a great country. So of course the rhythm changes from one location to another because it’s not the same characters. The action is not the same. You adapt to what you show. It’s not you who adapt, it’s the film. The film gets its own life, its own rhythm. You just have to understand it and follow it. That’s the way I try to follow.

HULLFISH: Is there a trick to making that transition from one pace to another or is it like an aria or a symphony where it has movements?

SCHNEID: There’s no trick. The only trick Is the Walter Murch trick of the blinking eye. I love this. It is something that everybody has done forever and he has managed to theorize it. It’s wonderful. I love it. But it’s so true.

HULLFISH: But a lot of what you were cutting — there were definitely dialogue scenes — but a lot of what you’re cutting couldn’t have been guided by blinks.

SCHNEID: No I’m not talking about eyes. You were talking about tricks and that’s just a little trick. Just cut before the blink, and that’s it. There are no tricks.

HULLFISH: Let me reword that. Was there any consideration when you had cut all your Italian — because all of the rushes came in at the same time for that — then you’ve got all this stuff from Mexico – when you butted them together — when you finally were able to put Italy with Mexico or America with Mexico or any combination — did you have to make changes to the pace around that transition to make the transition smoother?

SCHNEID: Not really. But of course, the first cut is too long. Always. But the structure really didn’t change much. I spent quite a long time with my first cut. I’m not very fast for my first cut, but usually, my first cut is not far away from the final one.

SCHNEID: Not really. But of course, the first cut is too long. Always. But the structure really didn’t change much. I spent quite a long time with my first cut. I’m not very fast for my first cut, but usually, my first cut is not far away from the final one.

Of course, we cut things and we change things and we have notes at the end and obviously there are changes, but the global thing — the choice of takes and the structure of each scene — doesn’t change much.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about the process. When I was starting to cut narrative, something I had to learn was, that no matter how hard you try to get that first cut great, just by seeing things in context, it changes. Let’s talk about how the film goes from your original cut — or even your original scenes before the assembly — to a final realization of those scenes.

SCHNEID: What I usually do is to cut one scene, then I try to cut the next one if I have it and go chronologically. If I can’t I just wait to fill the holes. I usually do an assembly with a missing scene card in between the scenes and I build as I go. And when I insert a scene I always try to make the connection correct — to make it work with the previous and the next one. There’s a bit of work here.

When I start a scene when I have the previous one or the last one I think of how the previous scene ends In order to correctly start the new one or changing the end of the previous one to start the new scene as I want it to start.

When I have two scenes together I rework a bit to have them going together well. And I keep on doing this until I have a complete assembly. Then most of the big things are done, but then you can start to think of what you’re taking out. What information you have doubled or tripled and what can you take out? Because strangely, taking out is adding. The trick is to feel the moment where if you add a little bit more then you lose a lot of things.

HULLFISH: When you were editing this movie, you were always editing in Italy even if they were shooting in Mexico?

HULLFISH: When you were editing this movie, you were always editing in Italy even if they were shooting in Mexico?

SCHNEID: Yeah. As I said, I started in Paris, then I went to Italy for a year and then I finished in Paris because I couldn’t stay for more than a year.

HULLFISH: Were you sending individuals scene cuts back to Stefano? Or were you waiting for him to see everything at the end?

SCHNEID: No. I almost never sent anything. A few times he asked for a quick first cut of a scene where he had questions. So I did that. They were usually in places where the internet connection was not good at all — if existing at all.

I think he trusted me, so we waited until he came back to have him in the cutting room and see everything.

HULLFISH: How were you getting the rushes? Was that all Internet-based or not?

SCHNEID: I think they were sending discs because of the internet connections. My assistants dealt with all of that, though.

HULLFISH: When you’re editing in your cutting room how are you monitoring audio? Left-center-right or just stereo or surround?

SCHNEID: Putting all of the dialogue centered. Otherwise, the atmosphere, the effects, the music, and everything is stereo. But left-center-right, yeah.

HULLFISH: Some people are starting to do 5.1 for picture cut. Is that something that you feel like you need to do or too much work?

HULLFISH: Some people are starting to do 5.1 for picture cut. Is that something that you feel like you need to do or too much work?

SCHNEID: No. There’s no need for that because it’s just for giving an impression. You have very talented people who do that much better than I do and I don’t have time for that because it’s time-consuming. If you start working in 5.1 and then it’s complicated.

Very often you have problems getting a wide atmosphere for one specific scene, so if you want to have it in 5.1 and then balance the rear loudspeakers, it’s getting really complicated. You need more time for that.

HULLFISH: When you get dailies in, how do you watch them and what are you doing?

SCHNEID: On this series I started different. Before that, I was looking at everything. I got the rushes. I looked at everything. I have my assistant put them in order — if it’s possible, in order of the scene — and I look at everything and I pay a lot of attention because the first time you look at the material is the moment where you get the best feeling of it. You respond to what is really good, which is not very good.

You have to trust your intuition, your feeling, the level of your skin response. It’s very important and I try to remember this. The first impression I have I try to remember it when I start to cut.

But on this series — since I had a lot of material — in order to get an idea of the scene, I looked at one chosen take for each setup. Then I start again and I look at everything so I know what I’m expecting and what I’m looking for and then I make choices which could be multiple.

I don’t choose one specific moment only. I make a few choices unless it’s really striking. If one really touches me, I go for it. But I make multiple choices at this point because I know it’s something I will come back to quite often, so if I have more choice I would feel more comfortable later, instead of going back to the rushes.

So from my first choice, either I do a second choice or I start to cut. Very often I try to articulate my scene at the beginning, It’s like dominos. One shot brings you to another. If it’s a framing thing or a response to a wide shot you want to go to a very close shot in order to give a big shock, so I tend to build my scene like this. I’m never thinking too much. Just feeling. Trying to feel and put myself in all of the characters. I’m each and every one of the characters in the scene. That’s how I do my choices.

So from my first choice, either I do a second choice or I start to cut. Very often I try to articulate my scene at the beginning, It’s like dominos. One shot brings you to another. If it’s a framing thing or a response to a wide shot you want to go to a very close shot in order to give a big shock, so I tend to build my scene like this. I’m never thinking too much. Just feeling. Trying to feel and put myself in all of the characters. I’m each and every one of the characters in the scene. That’s how I do my choices.

HULLFISH: Trying to be empathetic.

SCHNEID: Yes. I’m him in this situation. What should be my response? That’s the way I choose.

HULLFISH: When you were talking about having your assistant put together the things in order, are they making what some people call a KEM roll or a selects roll?

SCHNEIDER: Yeah, absolutely. It’s a sequence.

HULLFISH: Do you edit from that? Do you put that in your source monitor and use that as a source?

SCHNEID: Yeah, in the source to do my choice.

HULLFISH: And when you’re using that KEM roll sequence of all the selects, do you put locators in or are you just remembering the things that get a response from you?

SCHNEID: It depends on the amount of material and it depends on the length of the takes. I try not to use that many locators because I love it when it’s neat and it becomes very messy very fast. To make my choices, I make new sequences from this rushes assembly that’s it. I go to choice number one and then it’s much reduced and then maybe a choice number two which is even more reduced.

SCHNEID: It depends on the amount of material and it depends on the length of the takes. I try not to use that many locators because I love it when it’s neat and it becomes very messy very fast. To make my choices, I make new sequences from this rushes assembly that’s it. I go to choice number one and then it’s much reduced and then maybe a choice number two which is even more reduced.

That’s the beauty of digital. It’s so fast to go from one thing to another. My memory is visual. I remember more with my eyes than with anything else.

HULLFISH: Since you have such a strong sound background do you have a choice to build visually first or are you doing a little of everything or are you building sound first? How is the interplay between cutting a visual timeline and your audio timeline work?

SCHNEID: It depends very much on the scenes and on the films. It’s never the same. I don’t have a technique that I apply strictly each time so I adapt myself.

What I usually do is cut the image and yet I pay attention to the sound — the basic, minimum sound. And then when I finished the first cut then I do a little bit of sound to dress it a little bit without having too many tracks because it’s a mess to have too many tracks. So I try to reduce the tracks, and have everything in a few layers of tracks.

HULLFISH: Did you have to deliver all eight episodes at the same time, or did you have the benefit of getting through five episodes and then being able to see, “Oh, if I tweak this in episode one it would pay off more in episode five?”

SCHNEID: We had to deliver one and two first. But episodes one and two are very different I think because they are exposing the characters and the way we play it and they’re very heavy. A lot of things are happening.

So we did one and two. Episode three, I think, was not quite completed before I had finished four and five. When I finished Stefano’s first two episodes then I went with Janus Metz for episodes three, four, and five, and then we went in order.

HULLFISH

How do you deal with collaborating when a director is in the room with you finally?

SCHNEID: I think it’s the most interesting thing of all — the connection with the director. Usually, they are great people. Sometimes complicated, but great people. So I really love directors.

I think most of the work of an editor is to have this human relationship more than just cutting. But what is really interesting is the relationship with not only the directors but the assistants, the producers, and everything. Because it’s a very solitary work but at the same time you meet so many people.

Everybody is so important for the final result, so the rule — if there’s any — is to put your ego in the cupboard. Forget about it. No ego in the cutting room because otherwise, it’s hell. So forget your ego and just understand that even if directors appear very strong and very powerful, they are such fragile animals. You have to know when to say things and when not to say them, but always say what you think. That’s my motto.

HULLFISH: I’ve done a bunch of teaching and “leave your ego at home” is the number one rule for me.

SCHNEID: Absolutely. This is so true.

HULLFISH: I want to hear more about that relationship. So you’re talking about how exposed the director is. Stefano is a new director for you. How did you start to build that relationship and gain his trust and what was going to yield the best results?

SCHNEID: Comes naturally. You know that’s you’re not here by chance. He chose you, so he respects you and you know that. And of course, you respect him. I saw his films and I saw what he’s done and I love the ways of expressing what he wants to do, so the trust is here.

It’s like dogs meeting. Just sniff. Try to find your way. Where is your territory? It comes with time. And sometimes there are problems and you discuss them.

HULLFISH: For someone with such a great storied career is you, I think of your talent as an editor but also that human interaction. You don’t continue to work if people don’t like working with you.

HULLFISH: For someone with such a great storied career is you, I think of your talent as an editor but also that human interaction. You don’t continue to work if people don’t like working with you.

SCHNEID: Yeah. You don’t want to be where you’re not wanted.

HULLFISH: How long were you working with Stefano? What was the schedule?

SCHNEID: 16 months including the mix which was quite quick. The sound crew was fantastic on this one. They worked so quickly and so well.

I was really astonished. My idea of the Italian sound film industry was not very good, and I have to say that I was really impressed. Really impressed. Very great sound locations, good material, and very great people.

HULLFISH: How does it vary from country to country?

SCHNEID: I think each country has its characteristics. England for example is a very special place because they’re English and so they’re coming from another planet. I love them. I spent maybe four or five years in London in total cutting English films, but it’s another world.

They have their way of working — very calm and peaceful and it’s very British. I love it. I love it.

Americans are different but it’s interesting everywhere. Something which I really enjoyed all along my career was to go abroad — working in different countries because especially in editing, you are in the middle of things. You work for a long time. You stay for a long time with people in places, so you know the country: the way they think, the way they speak, the way they work. And I think it’s very enriching.

Americans are different but it’s interesting everywhere. Something which I really enjoyed all along my career was to go abroad — working in different countries because especially in editing, you are in the middle of things. You work for a long time. You stay for a long time with people in places, so you know the country: the way they think, the way they speak, the way they work. And I think it’s very enriching.

We editors are isolated. We are doing things by ourselves. Having our own problems, which we think are unique. And when you read interviews with other editors you realize that we all are the same. Everybody has the same problems. Find the same solutions. Have the same thoughts about things. It’s great to realize that you’re not alone.

HULLFISH: But there are differences. For example, some people watch the rushes backward. If there are eight takes, they watch take eight first. In reverse order.

SCHNEID: That can be done, depending on the director. If you know the director and if you know that the best takes are the last ones — which is not the case all the time.

HULLFISH: Early in the interview, you mentioned that you could see where the progression of the takes was going, as the director revised performances or blocking or camerawork. A lot of people want to see the end result and then watch the de-evolution of the scene.

SCHNEID: That’s what I did In a way with ZeroZeroZero, looking at one take for each setup and usually, it was the last one, of course.

SCHNEID: That’s what I did In a way with ZeroZeroZero, looking at one take for each setup and usually, it was the last one, of course.

HULLFISH: The circled take probably. Walter Murch had another very interesting thing that he pointed out in a recent podcast with me, which was: “It’s not the last take that’s best. it’s always it’s almost always the second-to-last take that is best.” That’s his theory.

SCHNEID: Sure, you shouldn’t pay attention to the circled takes, because you never know why it was chosen on the set. Maybe it was just to reassure the actor. So I rarely look at the script notes. I just trust what I see because what you see on the set is not what is on the film. It’s very different. It takes on another life when it is shot.

HULLFISH: Yes. And the director is also guided by the way they feel at the moment or how easily the setup happened or some fight that they had with the gaffer.

SCHNEID: Absolutely. That’s why I don’t like to go on the set because I don’t want to be influenced by what’s happening while shooting. It’s one of the roles of the editor to be the first spectator of the film. Directors must realize that because it’s very complicated to have distance from the material you’ve shot. It seems like the set is the heart of the action, but the action is in the cutting room.

HULLFISH: And on that great note, Herve, thank you so much for your time.

SCHNEID: You’re welcome. Thank you.

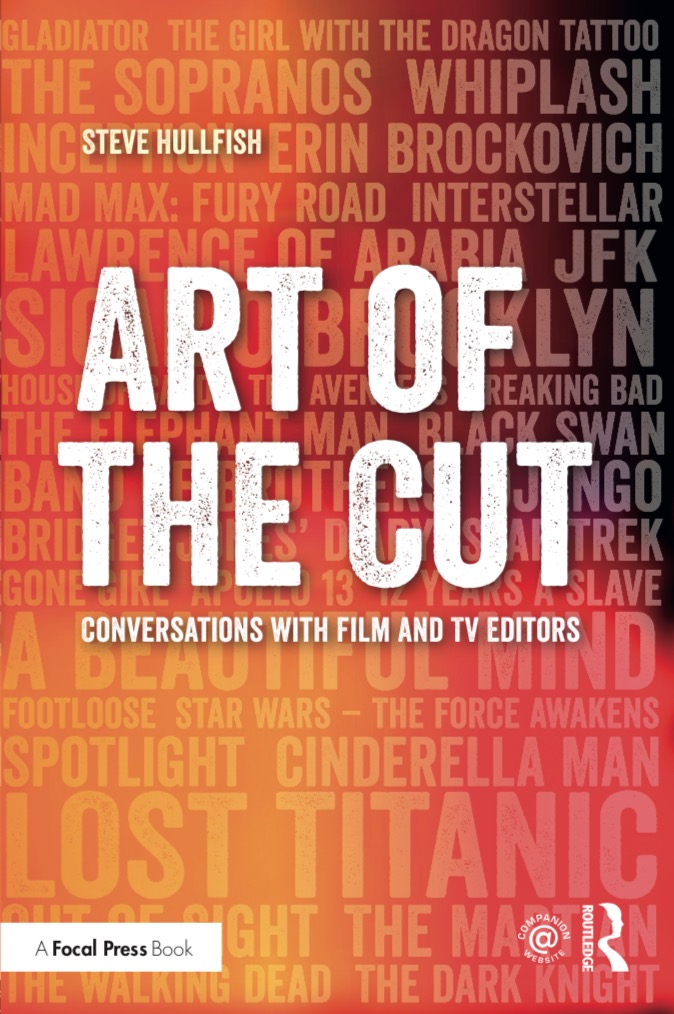

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now