Claire Dodgson has been working on animated films since starting as 2nd assistant editor on Corpse Bride (2005). She also assisted on Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009) as 1st assistant. She was an associate editor on The Tale of Desperaux (2008) and Despicable Me 2 (2013) before working as the editor on both The Lorax (2012) and Minions (2015). Art of the Cut caught up with her as she wrapped up her duties as editor on Despicable Me 3, completing the sound mix at Skywalker Ranch.

HULLFISH: So you’re at Skywalker Ranch? Are you enjoying that experience?

DODGSON: Oh yeah. It’s pretty fabulous. I was talking to Pierre, our director, and he said, “It’s like a reward for finishing this movie, being here.” It is! It’s so lovely. We’re really spoiled that we get to come here.

HULLFISH: I’m going to have to do another movie that will mix there just so I get a chance to go on holiday for a while. You’ve worked a long time and very hard to get there, right?

DODGSON: It’s kind of funny because I was here exactly two years ago just finishing Minions. It’s kind of nice the second time around knowing there’s light at the end of the tunnel, in the form of being at the ranch. It’s pretty great.

HULLFISH: Most of the people that read these interviews I would guess are not animation editors. It’s kind of pre-editing in a way, right? You’re editing before you have content. So, let’s talk just about how that’s different for the editor. Because you’re really involved in workshopping the film in way, right?

DODGSON: You’re right up there from the beginning when the story is evolving. Obviously it’s mainly the screenwriters and directors who are driving it. But you’re around to give input. As the editor, you’re the first member of the audience. You get to react to everything.

HULLFISH: Your background is mostly animation, correct?

DODGSON: Yes, I didn’t really discover what animation editing was until I started working in it as an assistant. I’d been working a lot in TV dramas as an assistant in the UK. I wanted to work in features, and I got the opportunity to work on Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride as a second assistant. When you get involved with animation you fall in love with it pretty quickly. Because you’re around when everything gets created.

HULLFISH: I worked at Big Idea which made an early animated feature film, so I got to see that process in depth. One of the things I’ve heard from so many people is that having limitation helps with creativity in many ways, but animation has no limitations. So having complete freedom, I would think, is kind of scary.

DODGSON: It is, but you really don’t have complete freedom. Especially at the beginning, when we first get script pages, we record the dialogue. So you’re recording people around the office who are game for a laugh, but they’re never going to win an Oscar. That isn’t having complete freedom. That limits you. That bolts you to the floor, anchors you down straight away. And sometimes I think that is where my most creative work comes in, because you’re forever just kind of trying to eke a performance out of something. And with the storyboards, yeah, they can draw anything, but you have to convince everybody they’re watching a film when really they’re watching black and white drawings. I totally understand that anything is possible and in a way, at the beginning, it is. Pre production is all about just kind of narrowing in your story and honing in on your characters.

HULLFISH: Does an animation editor have a super strong sense of story? Maybe stronger than a regular editor? Are some skills stronger and some skills weaker for an animation editor?

DODGSON: I don’t think so. I’d say one of the biggest differences for me is you don’t have any rhythm to work with other than the rhythm of the dialogue. You literally have still images and no performances to riff off. In live action you don’t often encounter that and I think for me that is the biggest difference as an animation editor is that at the beginning you have to give the film a beat and bring it to life.

HULLFISH: That’s exactly where I was going with that. Because, if you’re dealing with live action you’re able to cut on movement or decide when to cut on someone’s eyes. But with animation, you have nothing.

DODGSON: But sometimes that’s absolutely wonderful. You just made me think of a scene in Despicable Me 3 where Gru is having to tell Agnes that unicorns aren’t real. It’s a really nice, intimate scene and the storyboard artist drew very, very charming storyboards – a lot of emotion in it – and it was just this one frame of Agnes, all wide-eyed as Gru is trying to break the news to her…. I thought I just can keep cutting back to this frame and it is always going to be a funny reaction….You’re always looking for the motivation to cut, the reason to cut. Yes, most of the time that can be movement but the cuts are stronger if you find another motivation to cut.

HULLFISH: In the animation process, there’s a period when you’re using these nice emotional hand-drawn story panels, but eventually, you move to “layout” where these nice drawings are replaced with kind of robotic, unartistic unlit, unmoving 3D poses. Is that hard? Do you have to kind of remember the drawings?

DODGSON: Totally. First of all, our layouts have become particularly advanced. They can do a lot of animation and movement, but like you said, it’s lacking the expression. It’s something in the eyes. It doesn’t have any life yet.

HULLFISH: Could you explain to the readers what you mean by layout.

DODGSON: When it goes into layout it’s the first time when we have the actual sets, and the actual characters, and cameras. It’s the moment when you first move into 3D space. Quite often once you get the sets and the cameras, you start again from the ground up. So layout is mainly about figuring out what the camera is doing, and how everybody’s moving in the space.

HULLFISH: And at that point you can discover things: like the character can’t get from here to there.

DODGSON: True. Quite often, especially on the Minions movie, because they’ve got very, very tiny legs, you realize it will take them too long to exit screen. We work on scenes for a long time in storyboards, trying to find the shape of the scene. Then you finally all agree that this is the perfect scene in storyboards. And then layout comes along and all of your timings are completely obliterated because of the characters need longer to move in 3D sets. Then you have to figure out a way to try to keep the rhythm of the dialogue going and find space in the scene for the characters to move around. So the scene is destroyed and then reborn. It’s kind of interesting in a whole different way.

HULLFISH: Interesting. How locked in are you at that layout stage to what you did in the storyboards, shot wise?

DODGSON: Not at all, not at all. Because the layout team is super creative, and they’ll get their cameras in there, and give you rushes. For one action sequence, a car chase through a village, they were still figuring out the set for the village and they didn’t know how much set they needed to build for this car chase…. so what they ended up doing was pre-vising it and then I had to cut the pre-vis to figure out how many streets the car would drive through. And then everybody could build the set… So that scene I cut several times…. Sorry I can’t remember what your question was.

HULLFISH: How much are you locked in? Because the reason you do the storyboards is to let the rest of the animation team know, “This is what we’re getting.” Because it’s not like in regular editing. In live action, if it’s a conversation between the two of us we would have all of your close-up for the entire conversation and all of mine for the entire conversation. Plus, two shots and masters. In animation editing you don’t get that. They don’t just “roll film” on six cameras for an entire scene

DODGSON: Absolutely. But I totally have license when I get the layouts to change it. So if I think something is too slow I will use motion effect to speed it up. If I want something a bit longer then I’ll add freeze frames. I’ll picture-in-picture. I’ll do anything. One of the wonderful things about animation is that, as it goes through all these different departments, everything gets plussed. So you start with the storyboards, then it goes to layout. Layout says, “Oh we can do this. We can do that.” Then I get it and say, “That’s great but if we can do this, then it doesn’t have to be this long, or its even funnier.” Then you pass it back to them and then when it goes to animation, then it’s another level of creativity that gets laid on top of it.

HULLFISH: If you’ve got a live action scene shot and you don’t have the angle you want, you’re basically stuck. But as an animation editor you can say, “I wish I had a shot from directly above the character looking straight down.” And you can get it.

DODGSON: Yeah. It’s really good. The way the directors worked with the layout guys it is as if they’re shooting the scene. And then when the layout is delivered to editorial the first thing I do is grab Kyle, one of our directors, and we watch it through together and talk about all of the shots, much like a live action director would review dailies with the editor. That’s the moment where I can say, “Have you thought about this?” Or “I don’t quite understand what’s happening in this shot.” Or “The action is playing a bit too fast.” or “I’m a bit confused about where I am here.” Then we normally call in the head of layout and we discuss the retakes together. It’s really important that I speak up, because I’m the first audience and if I don’t understand what is going on then chances are the general audience won’t.

HULLFISH: Once you get past storyboards, are you editing more in reels or scenes? Or when you get to the layout phase, are you staying in a reel more because you’re kind of covering up the storyboards you have? Or are you still staying in a scene even though you’ve got layout?

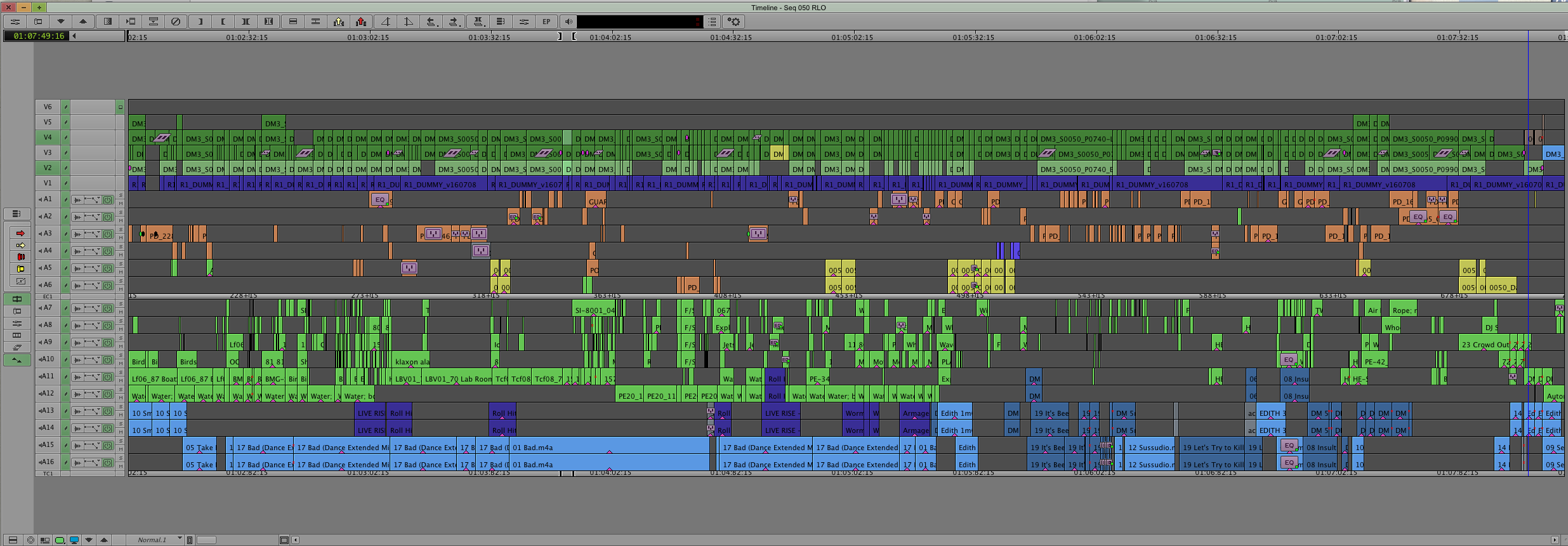

DODGSON: One of the things I always find watching animated films – and it’s something to do with the production process – everything is broken down into those 36 sequences, and everybody’s got a schedule about when these sequences need to be approved and everything. So everybody’s concentrating on sequences and you can often feel that when you watch animated movies. For that reason, I like to work in reels as soon as possible because I want that flow. I want to know where I’m coming from, where I’m going to. Psychologically, I like to working in reels because it’s one of my strategies to beat that sequence feeling of animated films. When I first started editing as a student, I was on a Steenbeck, so everything was in rolls, and that’s the attitude I’ve adopted whilst working in the Avid: I build KEM rolls of everything, so when I get my storyboards, the guys deliver it to me in a timeline. I can just load in my source monitor; or when I get the scratch it’s strung out so I can put it in my source monitor. The same with layout, because it’s just a way to not click so much.

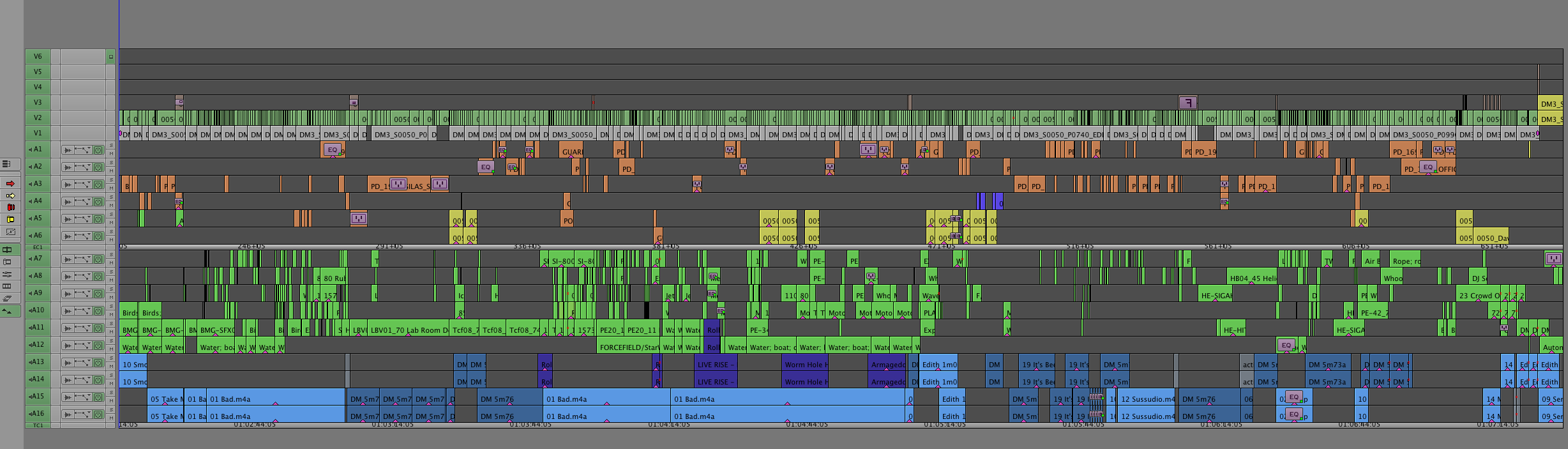

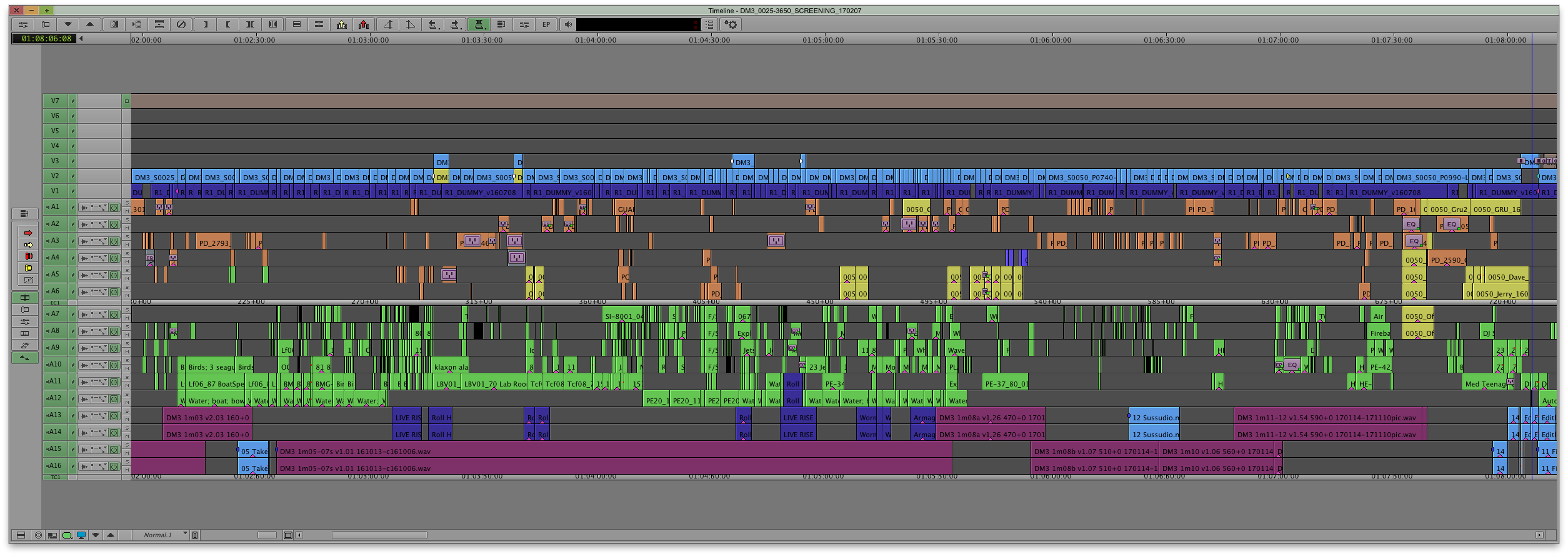

Another thing, which is a bit different to the way other animation editors work, is that I blow away the storyboards as soon as I get layout. As an assistant, I once worked for this editor and they had so many layers and layers and layers and layers of video… It was a nightmare as an assistant, especially back in the early days when you didn’t have as many video tracks. I also think then, it’s like the decision hasn’t been made. I use the storyboards as a guide whilst I’m cutting layout in, but then as soon as that sequence is approved it’s like Tetris. Everything goes down.

HULLFISH: “It’s like Tetris.” I like that. But that’s very unusual because everything I’ve ever seen is layers and layers and layers in animation: stacked final lit animation on top of rough animation, on top of layout, on top of storyboards. That’s why I do these interviews. Horses for courses, right?

DODGSON: Absolutely. As an assistant, I just saw too many things going wrong. I saw editors when they go back a version and they’re cutting it into the reel, all the video tracks would become patched the wrong way and what was on the bottom gets on the top, et cetera. I have all sorts of phobias from being an assistant. In terms of blowing away the storyboard timeline, I obviously up-version (saving an old cut before making revisions). We keep a bin of everything we ever show, so we always have the version that was approved. Once layout is cut in, if I was just to go back and turn on v1 and play it with the storyboards there, there would be big holes and it wouldn’t be playable anyway. I know back in the day they used to try and keep the storyboards on track with the layout so they always had a playable version of the current cut in storyboards because – like you were saying – the layout is missing a lot of the acting information. But I think layout is more developed now and we make these films so fast you can have animation within a matter of weeks on a sequence, especially as we get closer to screenings, they always try and get as much first-look animation in there as possible.

HULLFISH: Part of your job as an animation editor is this constant “feeding” of the other departments. The animators always need to be working, so you need one scene edited in storyboards so that some layout artist can start on it and get that scene done so that some animation artist can get done with it so some lighting person can get done with it. It’s constant. Somebody needs something at all times.

DODGSON: Totally. In editorial, we’re the smallest department, we’re this small cog in the middle of a giant machine. Everything we do keeps everybody else moving. And also, to add to that, there’s things with production dialogue quite often. Lines will be tweaked whilst they’re going through layout. Although we have recorded the actors in the scene already, it’s another opportunity to look at the scene and just clarify a few things, so they might decide to tweak a bit of dialogue, so we have to get that cut in very very quickly and approved so that it can feed animation. So there’s all these different elements that come in and the assistants in Paris – that’s very much their job – to keep production fed and to know whether the priority is to keep layout moving or animation.

HULLFISH: What are some of those deliverables? What did the assistants – since you were one yourself and are supervising them now – what do they actually have to do? Are they sending individual shots and post them as a QuickTime or something for a reference?

DODGSON: Well that’s how I used to do it. It’s thankfully developed now. The assistants make a QuickTime reference of the scene with a burn-in about how much I’ve sped a shot up or whether it’s a freeze frame and then they produce XMLs and they export the sound, and that all goes to animation. Basically it is like doing a change note by hand. The assistants take the last version of the scene that was delivered to production and the new version, and they gang roll it and note of all the changes between the old and new versions of the scene. They send these incredibly detailed emails that go out to the department about old shot length, new shot length, what I’ve done to it, whether the dialogue in it is scratch – therefore they shouldn’t animate it – whether it’s new production dialogue, whether I’ve moved the sync of the dialogue. It’s incredibly forensic and I think it’s very similar a VFX turnover…

HULLFISH: And they’re doing that on a shot-by-shot basis or a scene-by-scene basis?

DODGSON: Scene-by-scene basis, which can take them a long time if it’s a big scene. Sometimes we’ll actually split a sequence up into several parts so it can be published quicker.

HULLFISH: And when those new shots come in, is that something an assistant automatically sticks in and then you review, or do you feel like you need to cut those shots in over the old shots yourself?

DODGSON: They cut it in and I check it. I actually work closely with my associate editor on the animation. I like them to cut it in because once it’s gone through layout, its structure is locked. There may be an amazing animation performance idea that changes timings, but with animation it’s quite often eight frames on the end of the shot or something like that, so it’s not reinventing the scene. I like my associate editors to cut it in just because I want them to make sure everything lines up properly and everything is in sync, and they tidy up all of the temp music edits, quite often find associate editors haven’t done a lot of work with music, so it’s really good grounding in terms of how to extend music and loop things.

Animation “shoot” on Friday night at the end of the week, and so on Monday morning we have a lot of animation to bring in. The assistants build me a little roll and the associate editors and I sit in my room on and we watch all the animation that’s come in. That’s a really nice thing because then you’re seeing things out of order. There will be a couple of different sequences going through animation so things will be randomized and that can give you silly little ideas like, “Oh that scene actually plays really well into the other scene.” Any place where you can have happy accidents, I like to encourage them. My associate Rachel, when she’s cutting the animation in, she’ll put a little locator on all the shots extended by animation. I’ll go through and review all of those locators. And then what I’ll often do is put a “TBT locator” on it, which means “to be trimmed,” because quite often you’ll get shots that open up and you feel like maybe they don’t need all of those extra frames but perhaps there is a visual effects element I haven’t seen yet, but my first instinct is that I want to trim this, so I put the shot on “probation” by putting these little locators on. And then after a screening I’ll go through, and if I am still feel the same, that’s when I’ll start triming shots.

HULLFISH: What are you temping with? Are you trying to stay in the Despicable Me world?

DODGSON: Yeah, I do. Especially on this. It’s been quite easy because I’ve had two of Heitor’s (composer Heitor Pereira) scores to pick and choose from. Generally, with the temp music we’re kind of left to our own devices in editorial and it will be a while before Heitor becomes involved in the project, so we’re just trying to use the music as a tool. I think that when you are looking at black and white images, temp music is your color. When you haven’t quite got the full emotion in the storyboards or you don’t have the actual performance from the actor yet, music can provide you with great emotion. It’s really a tool we all use to help get everything feeling a bit closer to the finished film.

HULLFISH: Many live action people are trying to hold off on that temp music until almost you start screening for audiences, but for you, multiple people are screening the movie from a very early stage and they need that support, right?

DODGSON: Absolutely because you find a great sting and it can help with the timing of a joke and all sorts of things. I know I’m doing the composer absolutely no favours putting all this temp music in. I feel guilty about doing it, especially because on this movie Heitor came on about six months before we finished it, but for a year and a half they’d been listening to my temp, and the crew had a bit of temp love… But because music is such a strong storytelling tool, when you’re having to use so much imagination at an early stage, I can’t not use it.

DODGSON: Stop motion. I started as an assistant on stop motion, and then I cut a TV series that was 2D, and then Tale of Despereaux was actually 3D, and that was my first one as associate.

HULLFISH: Is there a technical difference between 2D and 3D? A workflow/process difference?

DODGSON: No not really. I think there’s a bigger difference between stop motion and CGI. Stop motion you work more into shots because you’ve got like twenty sets with animators working on shots. There’s only ever twenty shots live in the film that people are working on and there isn’t really any room for retakes, unlike in CGI, where you can go back to a shot and change it. So that’s very different. You’re locked in. What’s nice about it is: you’re in storyboards and then you go straight to a finished shot almost. I mean there might be some VFX in it but with stop-motion there’s no layout in between. They might do some camera tests or movement or something, but normally they don’t and you just start to get like a blocking version of the shot so everything’s got color and everybody’s wearing clothes.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about that blocking version of the shot. So you do a storyboard and everything is hand drawn, and then they go onto a little miniature set with little puppet creatures, and they would just stand them there or slide them around and say, “Okay he starts here and goes over here?”

DODGSON: Pretty much. It’s quite articulated blocking: key frames to block it out action with the cameras. Sometimes you would just get a still frame to come in so you could cut it in to just see if the framing was lining up with the shots on either side. In terms of the assisting work, you pretty much just had to give them the audio file and the frame count for that shot.

HULLFISH: So you’re at Skywalker Sound right now. What input are you having on the soundstage? Why are you there? It’s expensive to bring somebody from France to California, so you must have a purpose!

DODGSON: Gosh! You know sometimes I’m sitting on the stage and asking myself that very question. Obviously I have an Avid set up here just in case there’s any changes we need to make to the film. A lot of it’s about production dialogue, because I know that better than pretty much anybody. One of the things I’ve been doing on this film is – quite often we’ve felt a need for like an extra little giggle from one of the girls – and I can just go up into my Avid and grab something and give it to them. It’s mainly just to support the director. This show has quite a few action sequences and I’m thinking about my audience and about the little kids and I’m thinking about their ears and maybe “this is getting pretty loud now.” Especially at the end of the film, I was looking for places for us to try and take a breath – maybe lose some screaming here or make this a music moment rather than a sound effects moment. So there’s all that kind of thing that you get to input as well.

HULLFISH: I remember talking to someone that said that they were very picky about their original temp sound of thunder, and the real sound editors had replaced it with what they thought was better thunder, but it changed the rhythm or the flavor of the scene. Are you finding anything like that? Or are you just realizing that these guys are doing great work and it’s better than anything I put in there originally?

DODGSON: Most of the time when I hear what skywalker has done I’m super embarrassed that they ever heard the sound effects that I put in the temp. It’s a very humbling experience. There are a few things – like there’s a stomach sound effect that I’m just crazy in love with. Minions are often hungry in these movies – and every time skywalkers tries and change it I say, “No, I like my stomach growling sound effect.” There’s things you get a bit silly over.

HULLFISH: Did you record that sound by yourself around 10pm? Just stick a mic on your stomach? No?

DODGSON: (Laughs.) Yeah, at the end of one of the production meetings. No. I think it’s some really weird one like a whale-moan sound or something. But it just works.

HULLFISH: I did an interview today with Martin Walsh who cut Wonder Woman. One of the interesting things we talked about was the idea of a director and editor as a marriage. It’s a sense of trust, it’s a sense of protection. Talk to me a little bit about that director-editor relationship and what you feel like you need to do just as another human being.

DODGSON: On a regular working day, when we’re in the middle of production, I see my directors twice a day. I have them at eleven o’clock, and then I have them at half past two. The directors job is so hard, their role can be very stressful… I want them to feel like editorial is a safe space, like there’s no such thing as a bad idea and I always try all of their ideas whether I think “this is crazy” or not. And also just to be their cheerleader a bit. It’s a slog making these movies, and I always want to make them happy to be in editorial. My philosophy is: the more fun you have in the room, the more fun is on the screen, which – when you’re making children’s animated comedy – is an important thing. Everybody should be having fun. Everything is about the directors. I have learnt to read all of their “tells,” like, “I know you didn’t like this cut because you were tapping your foot along and then you stopped tapping at this moment, so why did you stop tapping your foot along?” It’s things like that. It’s a very interesting relationship because you go through quite stressful times. I always want them to know that I’m looking out for them as much as I’m looking out for the film.

HULLFISH: Can you tell me anything about these scenes?

DODGSON: The soup scene was one of the first scenes to be animated. Steve Carell and Kristen Wiig did a lot of great ad-libs for eating the soup. Everything played so funny, I had enough material to make the scene twice as long…. Cutting down ad libs is hard work because you are leaving out funny stuff but you know for the good of the film moments cannot play too long…

DODGSON: I love the minions singing! One day Pierre (director and voice of the Minions) gave me an audio file to listen to and it was him singing Pirates of Penzance’s in minioniese.. I fell off my chair laughing…. It was so unexpected. It ended up being the easiest scene to cut in the film because the song is so funny the scene effortlessly worked from the start.

HULLFISH: Is there anything else that you’re passionate about editing whether it’s pacing or story or things that when you’re with another editor you like to chat about?

DODGSON: One of the wonderful things about working at Illumination is – especially when I was cutting Minions – I had Ken Schretzmann, editor of Toy Story 3, in the room next door, cutting secret life of pets, and I had Greg Perler, editor of Enchanted and sing a few rooms away…. So I have some great editors to ask for advice if I’m struggling with something and I can just pick their brains…

I think the thing I’ve been trying to figure out is music, because I don’t have any musical background. That’s mainly what I end up talking to other editors about, trying to find out what scores they’ve been using or listening to. When you’ve been working with the same people for a long time, everybody is sick of hearing Mouse Hunt. It’s a really great score that’s “cuttable-up” and has lots of great stingy bits, so it’s really great for comedy.

HULLFISH: Mouse Hunt?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zgjUMHGjO0k

DODGSON: Mouse Hunt. It’s a great score. It’s got so many funny little moments in it. I use that a lot. I am sure the directors are tired of hearing it in their films…

HULLFISH: I’m buying that right now. I had the Carl Stalling’s Project CD a long time ago, that I loved for animation.

DODGSON: Ooo, what’s that?

HULLFISH: I got to see if I can find it. If I can find it I’ll send it to you. But it’s just the great old Bugs Bunny-type cartoon stuff.

DODGSON: Which is what you need sometimes.

HULLFISH: It’s been wonderful speaking with you. Enjoy your time at Skywalker Ranch.

DODGSON: Thank you, it has been great to talk to you.. I hope it all makes sense, sometimes editing is such an abstract thing to talk about…..

Thanks to Brandi Craig, Todd Peterson and Jada Sacco for transcribing this interview.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 Art of the Cut interviews have been curated into a book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV editors.” The book is not merely a collection of interviews, but was edited into topics that read like a massive, virtual roundtable discussion of some of the most important topics to editors everywhere: storytelling, pacing, rhythm, collaboration with directors, approach to a scene and more. Oscar nominee, Dody Dorn, ACE, said of the book: “Congratulations on putting together such a wonderful book. I can see why so many editors enjoy talking with you. The depth and insightfulness of your questions makes the answers so much more interesting than the garden variety interview. It is truly a wonderful resource for anyone who is in love with or fascinated by the alchemy of editing.” MPEG’s Cinemontage magazine said of the book: “In his new book, Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors, he gathers together interviews with more than 50 working editors to create a mosaic of advice that will interest both veterans and newcomers to the field. It will be especially valuable for those who aspire to join what Hullfish calls, “the brotherhood and sisterhood of editors.”

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now