This is Art of the Cut’s second interview with Eddie Hamilton, ACE. The first one was about Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation. Hamilton’s other previous work includes co-editing Kick-Ass with Oscar-winner, Pietro Scalia, ACE, and editing X-Men: First Class among many others.

HULLFISH: So you just finished Kingsman: The Golden Circle and, as we record this interview, you are working on the next Mission: Impossible movie. They’re both huge action-based movies. Is there a trick to editing great action?

HAMILTON: The trick to great action is being invested in the outcome of the sequence. It’s caring about the characters and understanding the stakes of what’s involved in the action sequence and what will happen if the protagonist succeeds or fails in their objective. If that’s clear for the audience then you’ll have the basis for a good action sequence. Secondary to that is the inventiveness of the choreography and the way the action is filmed and edited, after that, it’s about great sound design and music.

HULLFISH: I recently did an interview with Elisabet Ronaldsdottir who cut Atomic Blonde and she also brought up the importance of having a good dialogue with the fight and stunt coordinators. What was your interaction like there?

HAMILTON: The one thing about Kingsman: The Golden Circle that is very different from any other film I’ve done is I had twenty weeks of prep before they started filming. So twenty weeks of working with the fight choreographers on their sequences with storyboards and with previs and working on script development with Matthew Vaughn so the prep on all the big action sequences was done before they started filming. The whole opening of the movie is a very exciting, elaborate fight sequence followed by a car chase which was planned out almost shot-for-shot about two months before we started filming because it is so complicated and requires so many different cameras and ways of filming inside the vehicle. They had to make about seven different versions of a London black cab to enable the way that the camera was going to move around. And so that whole sequence was planned out with a combination of stunt visuals filmed on video, pencil storyboards, and clips ripped from other movies to represent the London driving geography shots. Then I added sound effects and music, along with my voice recorded into the Avid reading lines from the script, and all this was carefully edited together to tell the story of the opening of the film.

That was a lot of work. Several weeks’ work building that sequence so that Matthew could approve it and then we could film it.

Then I worked very closely with the stunt team throughout the shoot. Brad Allan is the fight designer and he has a fantastic team including a previs fight editor named Yung Lee. The team would design and film the fight on a video camera, Yung would edit it and add temporary visual effects and sound effects. Then he would show it to Matthew, and that would be imported by me – sometimes re-edited a little to fit the overall length of the sequence – and then Brad would go away and shoot that on the Alexa camera pretty much shot-for-shot.

For the most part, the credit for the action sequences and the initial editing of them belongs to Brad and Yung, who would send me QuickTimes of the sequences that they’d been working on that had been approved by Matthew.

Then the actors arrive and they are trained for several weeks. They train specifically to do the fight moves beat by beat, so they are prepared and rehearse and they are physically fit and ready to tackle the complexity of the fight sequence. And quite often if it’s a sequence in a room like a bar or the villain’s lair, they will build a stunt set out of cardboard boxes that represents the size of the space that the actual set will be. So the actors get to see physically how far they have to move around. A lot of the gags involving people flipping or flying through the air or involve wires to safely move the actors from A to B and soft sets so the actors and stunt guys don’t hurt themselves.

Then when everyone gets to the real set they’re ready to perform all the stunts and film very efficiently and quickly. They’re not making it up on the day. It’s all carefully planned.

The opening sequence in The Golden Circle was about ten days filming. So when you watch the film there is a fight between two characters in a black cab, it took about ten days to film and was very meticulously planned and every single shot was carefully choreographed. It took months and months from the original idea to the final edit. Probably longer than a year.

HULLFISH: Another big thing for me with fight scenes is the geography of where characters are in relationship to each other.

HAMILTON: It’s crucially important, something that we discuss on a daily basis while we’re editing. There’s a specific action sequence which is on a cable car in the Italian Alps. We incorporated these extremely wide shots into the action to clearly show the geography of what the cable car is doing in relation to what’s around it so that you understand quickly and clearly where the characters are and you understand the predicament that they’re in. Matthew is very precise about his use of geography in action to make it super clear for the audience what’s going on. It’s something that we refine over and over to make sure we’ve got it right. In those twenty weeks prep, when we’re building all the action sequences, we’re making sure that we’ve got the geography in there to make it clear.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about organizing footage for that 10-minute opening scene. How do you handle a sequence that is 10 minutes long?

HAMILTON: That is a very good question. What happens is that you end up with lots of bins, grouped by slate numbers. So, for one scene, I may have up to 20 bins and it will be named scene 4, and then in brackets, slate four to E and then I’ll have another bin for scene 4, and it will say slates F to H. So I have all the slates broken down like that. And then what I do is I watch through every slate, take the best bits and put them on a timeline, building this massive selects reel of everything in rough story order. And then I slowly, slowly squeeze it down until it’s the very best bits of action. Sometimes I’m literally over-cutting what they shot on video two months earlier and then I’m finding the best take and slotting it over so it’s the very best frames of the action to use for that beat. And then sometimes where I need to add more snap, I’ll snip out one frame or add camera shake or do a dynamic reframing on it or something just to make sure that this tiny little beat of story is absolutely precise.

And then it becomes a case of refining it hundreds of times to make sure that everything flows and your eyes are drawn to the right part of the frame and that the cuts play smoothly. It takes a very, very long time, and there are no shortcuts. It’s a very slow process of mining the footage to find the very best bits of action. The good news is Matthew mostly trusts my choices for action. So ninety-eight percent of what I present to him, he is in agreement that it’s the best. Very occasionally he’ll say, “Can I check that?” And then we will go back over the ten or twelve options. On a macro level, we may come back and look at a sequence after four months or five months of editing and decide it’s about ten seconds too long.

I hope that we’ve built a rollercoaster that has the right amount of excitement, character, humor and breathing space so there are proper peaks and troughs. After a year of working on every frame of the film with love, care, and sweat, I really hope that the audience feels like they’ve been taken through an exciting journey.

HULLFISH: One of the things I noticed in the first film was that many of the action shots were bespoke shots with very specific camera/action choreography. It wasn’t shot with your typical kind of coverage.

HAMILTON: That’s absolutely correct. It’s how Matthew Vaughn likes to shoot action. He works very closely with his action designer Brad Allan. He started working with him on Kick-Ass. They also collaborated on Kingsman: The Secret Service and this movie. That Hong Kong style of action is something that Matthew really embraces. He doesn’t like to shoot coverage for fights. He likes to plan fights, plan action, make sure that nothing is left to chance. That way the shooting days can be used constructively and precisely, so not a moment is wasted.

Some of the beats in the fight require very specific camera rigs that are hired just for one shot and it may take six hours to get ten takes, but it makes for an extraordinarily memorable moment. I am a collaborator with Brad and with Yung, his editor. I certainly share the credit for the sequences with them. I’m not taking full credit for any of this stuff. The choice of shots and how the shots slide together for this action is initially designed by them and then refined by me later over the course of a year based on how the sequence needs to play with the rest of the film, and how I can make the actual shot the best it can be – so that every single frame that is in the film is the best frame that’s available. It’s a team effort for the action sequences. The action sequences make up maybe twenty-five minutes of the film overall, but the film is two hours and fifteen minutes or whatever, so there’s an awful lot of drama and other kinds of editing which is necessary to make the film work. But certainly, for the action, I need wholeheartedly to give most of the credit to Brad and Yung and the rest of that team.

HULLFISH; With fight and action sequences that heavily choreographed and perfected, it must then be very difficult to edit when pieces of the fight or chase have to come out of the film.

HAMILTON: Yes it is. There are several ways of doing it. You can intercut it. So you’ll notice there are a couple of the scenes in the film that are intercut with parallel action. Where one character is doing one thing and another character is doing another thing we can choose when to cut back and forth. As a result of that, we can choose to ellipse out a small section of the action. The other thing is that quite often if the characters are exchanging blows you can just snip out three or four punches and it’s the same story. You just don’t have quite so much back and forth. There are also ways that you can try and hide cuts in muzzle flashes in the way that the camera moves to try and make you feel something more organic. So you don’t really sense that something’s missing, it just kind of feels natural. We use all those kinds of tricks to get the action down so that it feels the correct length for that specific moment in the film.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk a bit about the character and performance and dramatic moments. Is your approach to those scenes the same as your approach to action, or different?

HAMILTON: This is my current favorite method, which has evolved over the years… The first thing I do is watch a wide shot. I ignore the script because the script is a working document which is often revised on set, you can only work with what’s been shot. I watch a wide shot and get a sense of the story of the scene (which may be different to what’s on the page).

Then very quickly I will throw the scene together without refining the edits too much. I work with all the production audio tracks on the timeline. Normally it’s one or two mix tracks and all the iso tracks. Then I will watch all the dailies, usually in shooting order, although sometimes I’ll work backward to take one. I watch on the 65” OLED TV in my room. On this movie, I made the transition to standing while I edit and now I enjoy standing all day. Watching dailies is a time where I can stretch and move, and allow my body to change posture.

Then I duplicate my rough edit, and as I’m watching, I will find juicy sections and start slugging clips into a timeline using a different video layer for each set-up. By the end of my dailies review, I have a massive selects reel of memorable pieces of action and moments that an actor did something interesting or quirky or particularly relevant to their character. That’s very time-consuming.

Sometimes it will take me only ten minutes to do a first rough cut, but four or five hours to go through all the dailies, and another two hours to refine those massive selects reels back into an edited sequence. But I know that I have been through every frame and I’ve got what I consider to be the greatest hits of the performance on a single timeline. Then I can enjoy the process of refining the scene knowing that I’ve got all the best little looks and great ad-libs and line deliveries along with beautiful moments of character performance. I’ve been through all the gags and different line readings so I can figure out a way to make certain lines bounce off each other.

Then I’ll leave the scene for a day. I’ll go home and won’t watch what I’ve done. Next morning when I come in, I’ll watch the timeline silent and feel the rhythm of the scene. Then I’ll turn the mix track on and listen to the audio edits which are all over the place. Then I’ll duplicate the sequence, tweak it as necessary based on my fresh perspective, then spend a couple of hours doing a very precise and careful dialogue edit so that the dialogue track is beautifully smooth. Then I’ll put in sound effects and music.

Matthew Vaughn is a director who loves listening to temp score when reviewing scenes. So certainly when I’m starting to work I’ll play around with music, although I don’t let the music distract me. It’s really icing on the cake. And then I’m ready to present the scene to him. Often he would surprise me by walking in the day after filming, occasionally he would bring actors off the set, and he’ll go, “Hey Eddie. Do you have a sketch or an assembly of that scene? Let’s watch it with the guys.”

So sometimes I would have the privilege of showing an assembly of a sequence to the actors who had filmed it a couple of days before. He’s fairly confident that the scenes are working, otherwise he wouldn’t show them. He would give me a few notes and I would refine.

One big challenge we had on The Golden Circle was our first assembly was probably three hours fifty minutes of good scenes, which were eventually streamlined down to the two hours fifteen running time. That took months and months but was rewarding because we really did end up with the very best stuff.

HULLFISH: I’m fascinated by the fact that you said, “My current method.” This is one of the things I’ve been pointing out from writing the Art of the Cut book. Your methods should probably change. As you read about the way other editors work or you are presented with new ideas from maybe an assistant editor or even a new feature in the Avid software, your methods should be flexible – even just flexible to deal with novel situations, right?

HAMILTON: I’m constantly refining how I utilize the non-linear tools I have. One of the things that I love to do with the power of digital editing is find material very quickly. So when I’m with the director we can make progress on refining the edit very efficiently. I have many selects reels which contain the greatest hits for each scene. So if the director says, “What are the other moments that you picked?” I can call them up and run them immediately without hunting around.

The other thing that I do – which I’ve done for a few movies now – is to have the assistants make a massive line string reel so we can always go back and audition all the line readings extremely efficiently. I can go through and show we’ve got these wides, mediums, overs, and close-ups. And the director can choose to say, “Just run me the close-ups.”

When you’re working on a big budget movie, you have to make fast progress on the edit very efficiently, because the director’s time is limited… they may be shooting the next day, they may be prepping, they may be working with visual effects or music. Digital editing tools really help with that. And then I’m constantly refining how I lay out my Avid timeline so it’s efficient for my team to turn over dialogue and sound and visual effects so that everything is quick to find and it’s easy for everyone to see their way around.

I always ask my team if they discover a better way of doing something because I want to learn new tricks. I read your AOTC interviews every week to see if I can improve the way I work. I’m constantly trying to refine my techniques and get better. I strive to do my very best work every single day. It’s what gives me satisfaction on the job but also it’s an investment in my skills so that I’m hired again on another movie.

HULLFISH: That answered one of my other questions, which was about making selects reels not just for you as the editor, but also when it comes to handling notes and requests from the director.

HAMILTON: It’s important for action as well. When I’m over-cutting the stunt reels I’m still banking three or four options for each piece of action, just in case I think that another take was better for this beat. One of the car chases was not choreographed as heavily, and they would film sections with seven cameras, so I would have plenty of options. Then I would build a selects reel of those seven cameras and perhaps three of the cameras weren’t good for that tiny piece of action, but four of the cameras were great. Then I figure out we’re going to need a close-up of Eggsy to put it there for his point of view, and a shot of the speedometer, and a cutaway of guns firing and a reflection in a mirror. So a lot of the actual car chase was something where I did build it from scratch.

HULLFISH: Another thing you mentioned is editing while standing, which is something I’ve been doing for about eight or nine years now and I really love it for many reasons.

HAMILTON: It was a challenge to force myself to do it because I found out that I was very used to “getting in the zone” sitting down. Quite often when I started off I would stand up to watch dailies and to do a selects reel, but then, to get to the serious business of cutting the scene, I would find that naturally, I would want to sit down and get lost in the edit.

I listen to Zack Arnold’s Fitness in Post podcast which is now renamed Optimize Yourself.

HULLFISH: That’s a great podcast. I’ve been a guest on it myself and we talked about editing standing up.

HAMILTON: I listen to every episode of his podcast and I found myself thinking, “I’ve got to try this. It has to be for the best.” I value my physical fitness, I value my health, I value what I put into my body. I used to drink quite a lot of Coke Zero, Diet Coke and stuff like that. All I drink now is water and cups of tea -mostly decaffeinated tea.

When you stand up all day your body feels like it’s had a bit of a work out because you’re moving. And if I do sit down, after about half an hour I get itchy to stand up again. I find now that hours can fly by. I feel energized throughout the whole day and you don’t feel sleepy when you’re standing up. I feel more alert, I feel more creative, I feel more engaged with the creativity somehow.

I know I’m really late to the party with this. Walter Murch started standing years ago. But I’m very glad I caught on now. I’m in my mid-40s. I’ve hopefully got another 20 or 30 or maybe 40 years editing left in me. So I would recommend it to anybody. Recently I got one of those Topo ergonomic mats. (https://www.amazon.com/Ergodriven-Not-Flat-Anti-Fatigue-Calculated-Must-Have/dp/B00V3TO9EK/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1504816738&sr=8-1&keywords=ergo+mat+for+standing) As a result I constantly adjust my position throughout the day. They’re not cheap, but it’s something you use all day, every day. So it’s one of the best investments you could make. All my assistants are slowly transitioning to standing, I’ll be getting them a Topo Mat for Christmas.

HULLFISH: I got that Topo Mat too after Zach mentioned it on his podcast. It really helps with the foot and knee fatigue… better than standing on concrete, that’s for sure. One of the other things with standing is that I find, when I’m cutting an action sequence, I’m breathing fast. I’m really part of the scene and when you’re standing you just get to be part of the energy of the scene.

HAMILTON: Yeah you’re right. I watch these scenes over a thousand times, because I’m really trying to inhabit the mind space of the audience – where my soul is soaring with excitement, where I want the music to hit a triumphant peak or where I want the audience to punch the air and be speechless with amazement and wonder at what they’re seeing on the screen. You’re allowed to get into it more when you’re standing up.

Slowly I see the sequence coming together and I feel there’s light at the end of the tunnel. I start to get a glimpse of what the end product might be. It’s so exciting and rewarding to be the conductor of that. As the editor, you have control over every single thing that the audience sees and hears. The director then comes in and refines it with you, but that initial symphony is created entirely by you choosing the shots, choosing the sound effects, choosing the music, or working with a music editor to refine the music. And then slowly when you see it coming together it’s incredibly rewarding. The film goes through so many hundreds of iterations before landing on the final edit that people see. And obviously, if the audience gets into it and enjoys it then you’ve done your job. Everyone who’s reading this will likely be nodding. We’re invisible artists.

HULLFISH: You mentioned ad-libbing. Was there a lot of that and how did you deal with incorporating it?

HAMILTON: I watch all the dailies and I start to get a sense of what lines might play opposite other lines. I can hear Matthew directing the actors and saying, “try this, try this, try this, how about this, say this.” But quite often something rises to the surface. I’ve worked with Matthew since 2001 so we have a lot of years of experience and hopefully, I’ll reach a good working edit of a sequence fairly quickly, based on what I feel he will like and what will work best for the scene. I think it’s very important as an editor to have a point of view and to present something so you can say, “Here is a version of the scene that I think works for the movie,” and to be able to articulate why you’ve made every cutting choice or why every shot has earned its place in the scene. But often Matthew will have notes or we may re-cut the scene from scratch because something was fundamentally wrong with how the scene flowed in the context of the rest of the movie. There are several scenes in Kingsman where we tried many different versions.

A couple of times we did go round and round in circles and but not many. I would say to him, “These are the other options that you have here.” Sometimes we would try a different punchline and actually end up back where we started because there was something about that first gut instinct to the comic timing that did land best.

For one gag in the film, which probably gets the biggest laugh, Matthew had a great idea for a different punchline. We got the actors back, filmed the line, but I ended up doing a split screen with one of the actor’s reactions from the first take and the second actor’s performance from the reshoot. The combination of the two was the best result. I felt it when I was going through the dailies. I mocked it up on the timeline, we did the visual effects to combine the shots properly, and it gets a huge laugh. That’s very rewarding, but that’s an example of how we use the Avid tricks which we did not have years ago when we were cutting workprint. Now, we use split screens extensively to bring out the best in the material. We’re all working on that playing field of split screens and mattes and re-speeding clips to make the timing of the scene work better.

HULLFISH: To jump back a-ways in the interview, you mentioned that you are always pulling all of the iso audio tracks with you as you edit. Did I hear that correctly? That’s a fairly unusual way to work, I think.

HAMILTON: Yes that’s right, I always use all the iso audio tracks when cutting a scene. I never use the production mix track ever when I present the scene to the director. I go through and I pick the best boom mic and if necessary the best radio mic to play alongside the boom and then I carefully keyframe the audio so that the dialogue is as clean as it can possibly be based on the tools that I have. An actor’s performance is sacred and you should be giving it the best chance of succeeding in the edit, and in my opinion, this means never using the production mix track – which may have other bits of radio mic or off-mic sound mixed in.

The production sound mixer can’t do a perfect job moment by moment on the set. So I feel that for me to do the very best job I can – which will ripple down the entire post-production of the movie until we get to a dubbing stage – doing a really precise, clean, beautiful dialogue edit is best practice.

I spend almost as much time on that as I do on the fine cut. My cutting room is calibrated to 85dB. However, I don’t monitor at 85dB, I monitor at around 75 because 85 in a small cutting room is deafeningly loud. But I have the room calibrated correctly so that when I am sound mixing, my dialogue edit it will play smoothly and sound theatrical. Then the sound effects and music are mixed relative to that. So the iso tracks are all there but as soon as I do the dialogue edit with my chosen tracks, the rest are discarded. I can always match frame back if I want to double-check a radio mic or something later. I’m pretty precise about that first dialogue edit and then if I refine the scene I will use the same boom and the same radio mic if I swap out a take.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk a little about temp score.

HAMILTON: We used a lot from the first Kingsman which is great because all that musical DNA was there. The composers – Matt Margeson and Henry Jackman – built on that extensively. But we had to find two new musical identities – one for the villain (Julianne Moore’s character Poppy) and another for Statesman (the American cousins of Kingsman). They have a hoedown bluegrass country western feel with amazing fiddles and guitars and all kinds of terrific country textures which make their action sequences enormous fun to watch. For Julianne Moore’s character Poppy, we explored a lot of different ideas before ending up with the one that’s in the film now. Matthew loves making sure that the themes are carried through the film so that they become a part of the texture of the storytelling along with every other tool at his disposal as a director.

HULLFISH: You described the final scored music beautifully, but I’m sure that trying to get to something like that with temp score was not easy.

HAMILTON: Very complicated. We really struggled to temp Statesman. We went back through classic Western scores. To be honest we never found anything that was close to what Matthew wanted and we ended up using the stuff that the composers wrote for Statesman. And for Julianne Moore, we started out with a 50s sitcom idea that didn’t really stick. We tried some score from Tangerine Dream with that dark John Carpenter vibe. Matthew was worried it sounded too similar to the Valentine theme from the last film that was synth-based. We tried tracks from Serial Mom and Gremlins 2. But we never really got a texture with the temp score that we were happy with. It was very difficult. Poppy’s musical identity… we couldn’t find it with temp score and it’s something that we worked on for months before we settled on what Matthew felt was right.

For the big street battle in Poppyland, Matthew always wanted “Saturday Night’s Alright For Fighting” by Elton John, but the studio recording doesn’t have a massive rock and roll ending, so I dug around and found two live versions from the late 70s, one from Wembley and the other from the Royal Festival Hall I think, I used a combination of the guitar solos and drums from both to create the big finale you hear in the movie as the battle builds to a climax.

HULLFISH: Another thing you discussed was that your comedy stuff didn’t go through a lot of revisions, where the action stuff or drama stuff did. It’s interesting that the initial take of what’s funny is often the thing that sticks best. Not always, but often.

HAMILTON: Kingsman is full of light-hearted entertaining moments. One of the scenes that I’m most proud of, which was the hardest to do, is a sequence where Eggsy is having dinner with his girlfriend’s parents and he is meeting them for the first time. They ask him some very difficult questions and he finds a clever way of answering them. It was a scene which had classic dinner party coverage of eye-lines with multiple shots and sizes. Wides, mediums, tights, overs, every single line to every eyeline in sequence. So you end up with an enormous amount of footage which any editor who has done one of these scenes will know is an enormous jigsaw puzzle of reactions and lines and moments and tiny little beats to make the conversation feel like it’s flowing and keeping all the characters alive.

That sequence took me a very long time. Maybe ten days of solid editing to build a first assembly. I had this idea for a waltz playing over it and I found this piece of music that seemed to fit. This was going to flow like a dance. I presented it to Matthew with all these interesting transitions that I built with these close-ups of food courses being swapped over. You’ll see there are close-ups of posh plates being put down with fast dissolves, fun stuff like that which is part of the wish fulfillment of these films.

I remember when I watched James Bond movies growing up I would see Roger Moore and Sean Connery visiting these far-flung locations. In Octopussy they went to India and they filmed in these incredibly exotic locations which you would never dream of visiting. As a result, I would experience spy wish fulfillment. I would see Roger Moore on this exotic beach or in this exotic mountain hideaway. A lot of the Kingsman vibe is based around that sense of fun the Roger Moore Bond movies had and that sense of wish fulfillment was always an essential ingredient in Bond movie.

In Kingsman you’re going to a royal palace to enjoy a dinner with the king and queen of Sweden. And you’re seeing the finery and the splendor and the delicious food and the wine and crockery and cutlery. Anyway, all those things were going through my head as I was building the sequence and I presented it to Matthew and he said, “That’s great. I don’t think we need to change that.” So the scene stayed that way from the first assembly all the way through to the final edit. What you see in the film is how I landed at the end of a very thorough process of trying to maximize the best in what they shot out of the mountains of coverage.

HULLFISH: You mentioned that the first assembly came in at over three hours. Tell me a little bit about the difficult decisions and the answers to solutions of cutting out more than an hour of a film.

HAMILTON: It comes down to removing information that the audience doesn’t need. Sometimes that they can fill in themselves; it’s superfluous to the core story that you’re telling; sometimes it’s to increase the mystery around a certain piece of story; quite a lot of the time it was to reduce characters traveling, so that we would set them up as going somewhere and then just find them in that location without necessarily showing how they travelled there.

We worked on transitions in this film probably harder than any movie I’ve worked on before. Every single transition in this film (where we’re changing from one story to another) was refined many times over months of editing.

Our little scene cards which were up on a whiteboard were shuffled around many times while we tried to balance Eggsy’s story with Poppy’s story with the Statesman story to make sure that we stayed with each character as long as we needed to invest in them before we moved on to another story. And quite often we ended up staying longer than we initially thought because ironically the film felt slower when these bits of story were in shorter sections. The audience likes spending time with a character and going on that journey with them before you switch over. That was one thing that we played with a lot… how long you spend with each character and if you can ellipse out bits of story so that the audience fills in the blanks, and if you can make the transitions organic and interesting so you never feel like the channel is being changed too abruptly as you watch. Your emotions are being guided and the stakes of the story are clear and the mystery of the villain’s plot is building in a tantalizing and mysterious way so that you’re never confused but you’re always intrigued. It’s all those ingredients which you refine and refine and refine.

Our little scene cards which were up on a whiteboard were shuffled around many times while we tried to balance Eggsy’s story with Poppy’s story with the Statesman story to make sure that we stayed with each character as long as we needed to invest in them before we moved on to another story. And quite often we ended up staying longer than we initially thought because ironically the film felt slower when these bits of story were in shorter sections. The audience likes spending time with a character and going on that journey with them before you switch over. That was one thing that we played with a lot… how long you spend with each character and if you can ellipse out bits of story so that the audience fills in the blanks, and if you can make the transitions organic and interesting so you never feel like the channel is being changed too abruptly as you watch. Your emotions are being guided and the stakes of the story are clear and the mystery of the villain’s plot is building in a tantalizing and mysterious way so that you’re never confused but you’re always intrigued. It’s all those ingredients which you refine and refine and refine.

And the other thing that we did was test screen. We listened to notes from the studio. We invited key collaborators into the process. I would invite editing friends of mine quite late in the process because I was so close to the film and I needed fresh perspectives. I wanted to hear their honest, brutally harsh but necessary criticism, so that we could take a long hard look at the movie and make healthy decisions to get the running time down, so the film didn’t outstay its welcome. But mostly it was listening carefully to the audience every step of the way. I think we did three large screenings to several hundred people. In between we did multiple friends and family screenings to 10, 15, sometimes 30 people. So once or twice a month through the entire editing process we would screen the film to really nail down the details of what was and wasn’t working and check where the laughs were coming.

Throughout, we were careful to keep the grace notes of the story. That’s what makes the audience engage. It’s the little character moments which make you fall in love and care deeply about our heroes so that you’re invested from beginning to end, and I hope it works. You never know how the film will be received. There’s a lot of factors you don’t have control over but we know that we made the very best film that we could for the audience and we hope they respond positively towards it. It’s predominantly about reminding the audience that going to the movies can be fun.

HULLFISH: That’s definitely how I felt about the last Kingsman movie.

HAMILTON: And hopefully you’ll feel the same way about this one. We really worked hard to create something that has that very unique original feeling which is directly from Matthew Vaughn’s imagination onto the screen.

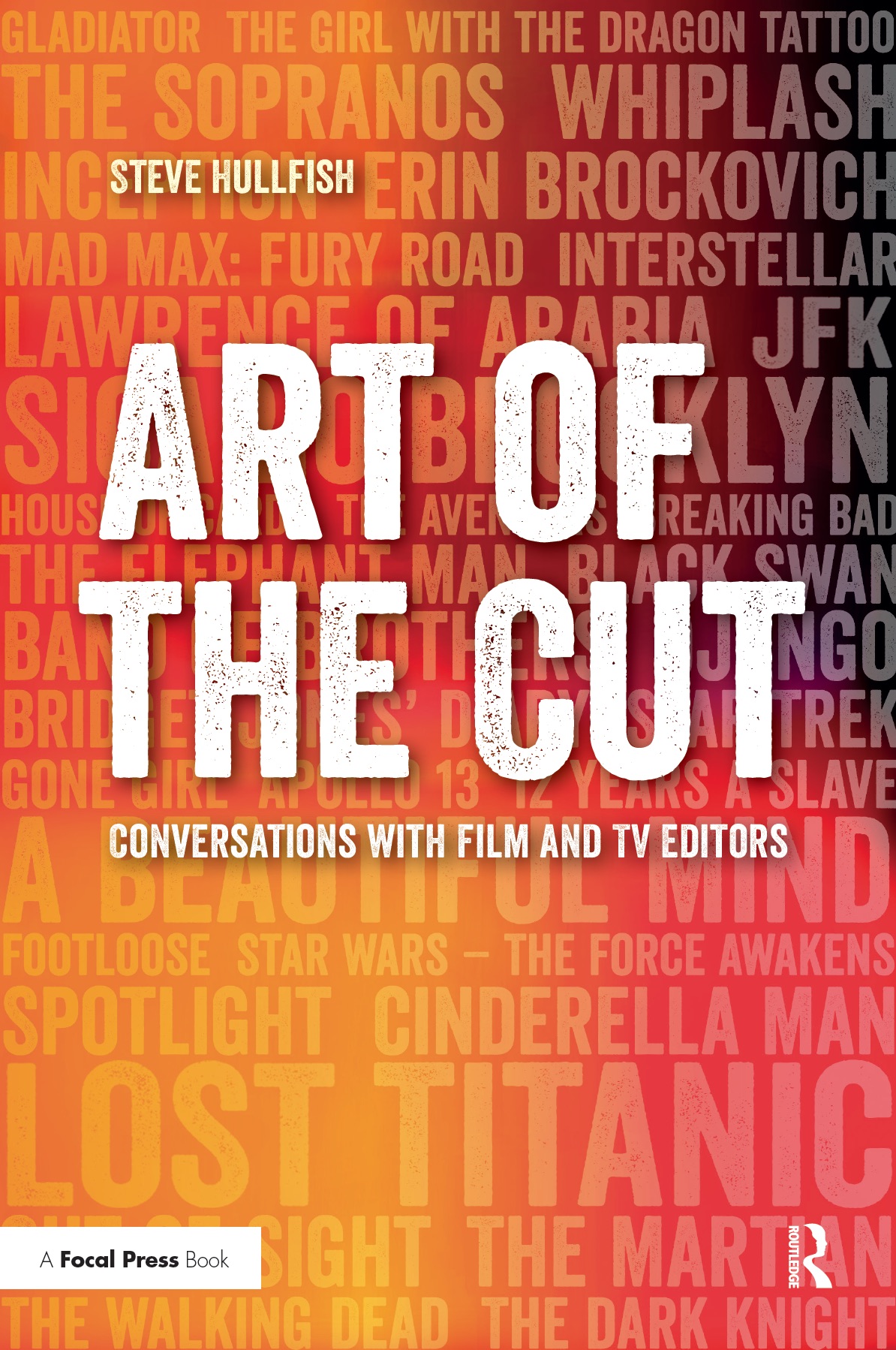

HULLFISH: Eddie, it’s been a pleasure speaking with you again. We’ll have to touch base again when Mission: Impossible Six comes out. And thanks for the great picture of the team with my book!

HAMILTON: A pleasure Steve, a big shout out to my trusty editorial team without whom the entire process would’ve ground to a halt very quickly… Riccardo Bacigalupo and Tom Coope (First Assistants), Ben Mills and Robbie Gibbon (VFX Editor and Assistant), Christopher Frith (Second Assistant) and Ryan Axe (Trainee). And thank you, Steve, for taking the time to reach out to the editing community and allow us to share our cutting room stories on your site. Enjoy the movie everybody.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 Art of the Cut interviews have been curated into a book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV editors.” The book is not merely a collection of interviews but was edited into topics that read like a massive, virtual roundtable discussion of some of the most important topics to editors everywhere: storytelling, pacing, rhythm, collaboration with directors, approach to a scene and more. CinemaEditor magazine said of the book, “Hullfish has interviewed over 50 editors around the country and asked questions that only an editor would know to ask. Their answers are the basis of this book and it’s not just a collection of interviews…. It is to his credit that Hullfish has created an editing manual similar to the camera manual that ASC has published for many years and can be found in almost any back pocket of members of the camera crew. It is an essential tool on the set. Art of the Cut may indeed be the essential tool for the cutting room. Here is a reference where you can immediately see how our contemporaries deal with the complexities of editing a film. In a very organized manner, he guides the reader through approaching the scene, pacing, and rhythm, structure, storytelling, performance, sound design, and music….Hullfish’s book is an awesome piece of text editing itself. The results make me recommend it to all. I am placing this book on my shelf of editing books and I urge others to do the same. –Jack Tucker, ACE

The first 50 Art of the Cut interviews have been curated into a book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV editors.” The book is not merely a collection of interviews but was edited into topics that read like a massive, virtual roundtable discussion of some of the most important topics to editors everywhere: storytelling, pacing, rhythm, collaboration with directors, approach to a scene and more. CinemaEditor magazine said of the book, “Hullfish has interviewed over 50 editors around the country and asked questions that only an editor would know to ask. Their answers are the basis of this book and it’s not just a collection of interviews…. It is to his credit that Hullfish has created an editing manual similar to the camera manual that ASC has published for many years and can be found in almost any back pocket of members of the camera crew. It is an essential tool on the set. Art of the Cut may indeed be the essential tool for the cutting room. Here is a reference where you can immediately see how our contemporaries deal with the complexities of editing a film. In a very organized manner, he guides the reader through approaching the scene, pacing, and rhythm, structure, storytelling, performance, sound design, and music….Hullfish’s book is an awesome piece of text editing itself. The results make me recommend it to all. I am placing this book on my shelf of editing books and I urge others to do the same. –Jack Tucker, ACE

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now