Alexandre De Franceschi, ASE (Australian Screen Editors) has been an editor for more than 30 years, cutting over a dozen feature films in addition to a career as a sought-after commercial editor. He has edited numerous TV series and feature films with director Jane Campion and John Curran and recently edited Lion, the critically acclaimed film from director, Garth Davis. Lion is a Best Picture Oscar nominee this year, and was nominated in 5 other categories. I liked this film so much I paid to see it twice!

HULLFISH: I just watched Lion and absolutely loved it. It was masterfully done, just a beautiful job. I walked out crying.

DE FRANCESCHI: That was the intention. That was the idea. It’s so good to see that it’s touching so many people.

HULLFISH: Does it mean anything to you as an editor to be working on a film that is based on a true story? Do you feel any special obligation?

DE FRANCESCHI: Absolutely. One feels obliged to tell the truth. It was probably the main reason I wanted to take on this movie. It was a set of circumstances on how it came to me. Three years ago we were nominated for some Emmy’s on a TV show that I had been cutting. The production company, See-Saw Films, was throwing a party in West Hollywood, and I was sitting at a table with Garth Davis who’s the director of Lion. He was also one of the co-directors of the TV show, Top of the Lake, so I knew him. I hadn’t edited with him because we had two editors on the show. I was cutting for Jane Campion and Garth had his own editor. So Garth Davis was sitting there, writer Luke Davies, whom I had socially met before, was sitting across and then in between the two of them was this Indian guy, and we got to chat, he told me his name was Saroo Brierley and he had just been at a conference at Google. I was curious.  One thing leading into another, he ended up telling me his life story and then he turned to Luke Davies and said: “And this guy is going to adapt my book” and then he turned to Garth Davis and said “And this guy is going to direct it” and then he pointed at producers Emile Sherman and Iain Canning, on the opposite side of the table, and said: “And those guys are going to produce it”. And I thought to myself: “And I’m going to cut it.” I wanted to be part of such an extraordinary, fascinating story. He was so spontaneous and generous. He had such a good heart in telling his story and I thought, “You know, this story is really worth telling and I want to be part of it.” And also I had been following Garth’s directing and I was really impressed with his way of dealing with both the camera and the actors. So I approached him and I said “I want to cut this movie. What do I need to do to edit it?” and he said, “You just have to love it and you just have to do it from a very honest point of view and you just really need to do it because you want to”. There was no need to tell me that, I don’t cut because I need a job. I cut because I love editing and I’ve been doing it for a long time now. You get to that stage in your career where a lot of work is on offer, and one needs to choose carefully and think: “There has to be something in the movie or the show for me to really commit and put all that time and effort, and it has to come from the heart, you know?” Otherwise what’s the point?

One thing leading into another, he ended up telling me his life story and then he turned to Luke Davies and said: “And this guy is going to adapt my book” and then he turned to Garth Davis and said “And this guy is going to direct it” and then he pointed at producers Emile Sherman and Iain Canning, on the opposite side of the table, and said: “And those guys are going to produce it”. And I thought to myself: “And I’m going to cut it.” I wanted to be part of such an extraordinary, fascinating story. He was so spontaneous and generous. He had such a good heart in telling his story and I thought, “You know, this story is really worth telling and I want to be part of it.” And also I had been following Garth’s directing and I was really impressed with his way of dealing with both the camera and the actors. So I approached him and I said “I want to cut this movie. What do I need to do to edit it?” and he said, “You just have to love it and you just have to do it from a very honest point of view and you just really need to do it because you want to”. There was no need to tell me that, I don’t cut because I need a job. I cut because I love editing and I’ve been doing it for a long time now. You get to that stage in your career where a lot of work is on offer, and one needs to choose carefully and think: “There has to be something in the movie or the show for me to really commit and put all that time and effort, and it has to come from the heart, you know?” Otherwise what’s the point?

HULLFISH: To me it seemed like this was a very difficult job to get what I call the “macro pacing” – deciding when you hit the big story points and how long you take to get from – for example – Saroo getting lost to being adopted to leaving his parents to telling his friends his story. Talk to me a little about those decisions and how you had to mold the picture through those big tent-pole moments.

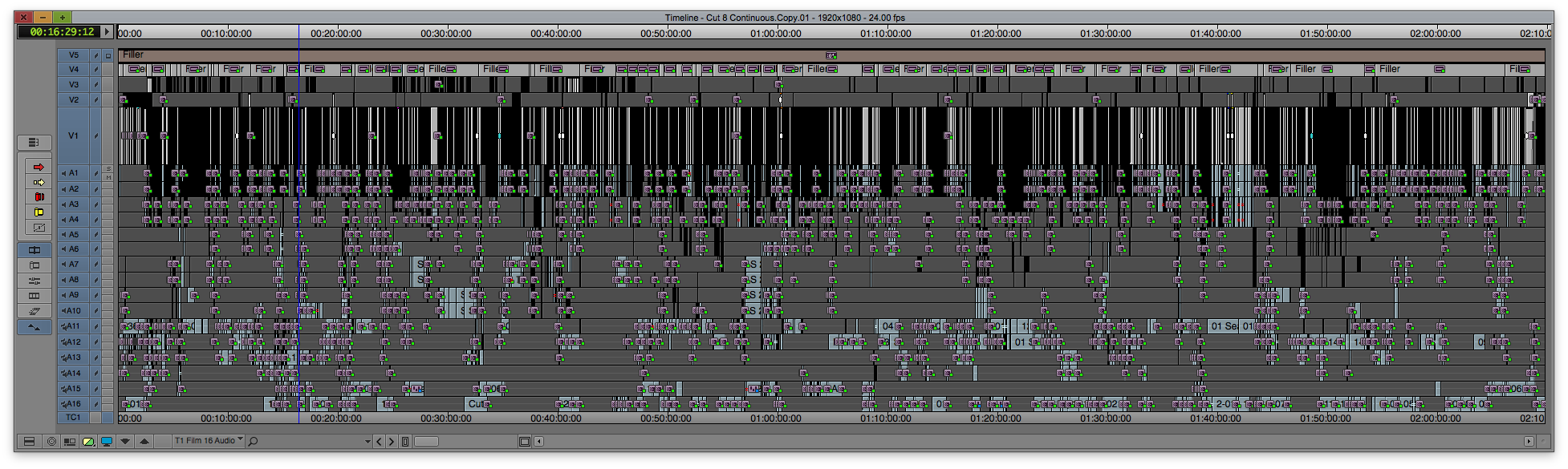

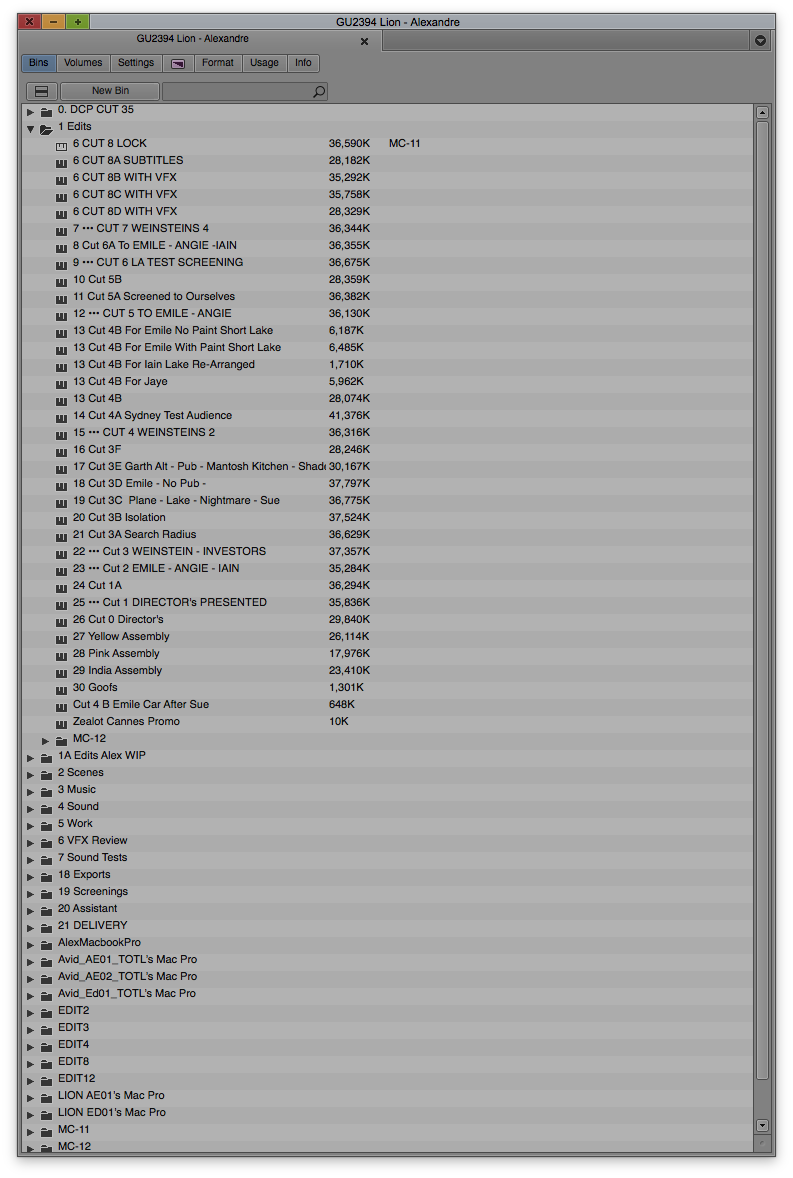

DE FRANCESCHI: Garth had a very clear movie in his head. He did a lot of rewriting (uncredited, needless to say) during the shoot and then quite a bit more during the edit. From start of shoot to end of edit, the script was evolving on a daily basis. Anybody who has worked on a movie with flashbacks knows that flashbacks have a tendency to move around. I learned that lesson the hard way on Painted Veil so I was prepared for a rocky edit. You can say that there are two movies in Lion. There is the adult Saroo and the young Saroo and they are two very differently paced movies. Different camera approach, different directing approach, all very deliberate. Garth wanted to portray two worlds that were really different and apart from each other until they meet at the end. We had over two-hundred and fifty hours of footage. Normally, when you work on a scene, you open your bin, you work on that scene then you close that one and move forward. With this movie at one point we had up to forty scenes open at once, working on all of them at once. I’ve never done that before. Especially on the search and the flashbacks and all that – it was all constantly interlacing. It was a fascinating way to work and very spontaneous, totally organic. Garth was only trusting his feelings and what made him feel good within the edit itself, so if the story was lingering and he was not paying attention, something was wrong with it and we kept pounding it until it was emotionally hitting the mark. It was a very ambitious script it had, from memory, two hundred and sixty five scenes in a hundred and thirteen pages which is substantial for drama. All the characters were really built in that script. We had a great side story with the brother. We had a great side story with the girlfriend. But that was a two and a half hour movie, which nobody wanted. Once we started cutting it down, the side stories had to give way to the main story, namely Saroo and Saroo finding his mom. This was a round-about way to answer your question, but in short the management of the “macro-pacing” came through the loss of side stories and the need to keep the main story centered on Saroo and his search. It didn’t come about easily.

DE FRANCESCHI: Garth had a very clear movie in his head. He did a lot of rewriting (uncredited, needless to say) during the shoot and then quite a bit more during the edit. From start of shoot to end of edit, the script was evolving on a daily basis. Anybody who has worked on a movie with flashbacks knows that flashbacks have a tendency to move around. I learned that lesson the hard way on Painted Veil so I was prepared for a rocky edit. You can say that there are two movies in Lion. There is the adult Saroo and the young Saroo and they are two very differently paced movies. Different camera approach, different directing approach, all very deliberate. Garth wanted to portray two worlds that were really different and apart from each other until they meet at the end. We had over two-hundred and fifty hours of footage. Normally, when you work on a scene, you open your bin, you work on that scene then you close that one and move forward. With this movie at one point we had up to forty scenes open at once, working on all of them at once. I’ve never done that before. Especially on the search and the flashbacks and all that – it was all constantly interlacing. It was a fascinating way to work and very spontaneous, totally organic. Garth was only trusting his feelings and what made him feel good within the edit itself, so if the story was lingering and he was not paying attention, something was wrong with it and we kept pounding it until it was emotionally hitting the mark. It was a very ambitious script it had, from memory, two hundred and sixty five scenes in a hundred and thirteen pages which is substantial for drama. All the characters were really built in that script. We had a great side story with the brother. We had a great side story with the girlfriend. But that was a two and a half hour movie, which nobody wanted. Once we started cutting it down, the side stories had to give way to the main story, namely Saroo and Saroo finding his mom. This was a round-about way to answer your question, but in short the management of the “macro-pacing” came through the loss of side stories and the need to keep the main story centered on Saroo and his search. It didn’t come about easily.

HULLFISH: Was that your first cut? Two and a half hours?

DE FRANCESCHI: The very first cut was about two forty-five maybe and then that was cut to two thirty so you could call that the first cut, yeah. Everything was in there. Absolutely everything except for a couple of scenes that just didn’t work out on the day. But, it was too long. The film wasn’t boring, far from it but there were too many emotional peaks and people had trouble coping. They were exhausted before reaching the end. So we came to terms that we had to centre the journey and the side stories became redundant, as interesting and captivating as they were. So the process was to reduce. It was easy to take it down to 2:15. Taking it down to 2:10 was difficult. At 2:08 we thought we had a really good movie. Two hours, which it is now, everyone is enjoying it and we have six Oscar nominations, so we’re not going to complain.

HULLFISH: Sound design was something that I was thinking about during the beginning of the movie, especially in India.

DE FRANCESCHI: I’m glad you noticed. We put a lot of time into it because the intention with the sound is you want to hear things from the perspective of this little boy and children don’t hear the world the way we hear it. So the emphasis was, “How would Saroo hear the world?”. A good example would be when Saroo arrives to the train station half-asleep in his brother’s arms. It’s super busy and noisy, there are trains around, there are crowds. Then he goes to sleep on the bench, his brother trusts that he will listen to the instructions not to go anywhere, but he’s already asleep, just thinking of the delicacies he had seen earlier at the market, the thought puts him to sleep. Then he wakes up. The silence wakes him up. The silence is the trigger. All the noise is gone, the station belongs now to the world of crickets. It is abandoned and silent and a little scary because there are stray dogs around. So as anyone would, he looks for his brother and finds cover in a train car. This time the silence puts him back to sleep. He half-wakes with the sun and the faint movement of the train car, the sound is really distant but then we cut to him fully waking up and hear the full sound of the train. From here onwards, the train sound increases to monstrous proportions, up to almost an unbearable moment where he is banging the doors and looking around and screaming and yelling. This approach to sound is kept all through India. The chaos of Howrah station. Unbearable. The silence broken by a distant crow and the sound of an abused child crying in the orphanage. Chilling. Once we get into the world of Tasmania and Australia (when he is adopted) the soundscape becomes more adult and more “normal”. We had the most beautiful sound designer I have ever worked with, Robert Mackenzie. He is also nominated for his work on Hacksaw Ridge.

DE FRANCESCHI: I’m glad you noticed. We put a lot of time into it because the intention with the sound is you want to hear things from the perspective of this little boy and children don’t hear the world the way we hear it. So the emphasis was, “How would Saroo hear the world?”. A good example would be when Saroo arrives to the train station half-asleep in his brother’s arms. It’s super busy and noisy, there are trains around, there are crowds. Then he goes to sleep on the bench, his brother trusts that he will listen to the instructions not to go anywhere, but he’s already asleep, just thinking of the delicacies he had seen earlier at the market, the thought puts him to sleep. Then he wakes up. The silence wakes him up. The silence is the trigger. All the noise is gone, the station belongs now to the world of crickets. It is abandoned and silent and a little scary because there are stray dogs around. So as anyone would, he looks for his brother and finds cover in a train car. This time the silence puts him back to sleep. He half-wakes with the sun and the faint movement of the train car, the sound is really distant but then we cut to him fully waking up and hear the full sound of the train. From here onwards, the train sound increases to monstrous proportions, up to almost an unbearable moment where he is banging the doors and looking around and screaming and yelling. This approach to sound is kept all through India. The chaos of Howrah station. Unbearable. The silence broken by a distant crow and the sound of an abused child crying in the orphanage. Chilling. Once we get into the world of Tasmania and Australia (when he is adopted) the soundscape becomes more adult and more “normal”. We had the most beautiful sound designer I have ever worked with, Robert Mackenzie. He is also nominated for his work on Hacksaw Ridge.

HULLFISH: You were mentioning the train and how the train sounds got louder and louder and I remember a cut which I loved which was: you’re hearing Saroo and his crying and screaming is in lip-sync where he’s screaming “help me, get me out of here, let me out of this train,” and then there’s moments where he’s talking and screaming but there’s not sound of him talking and screaming. It’s that frustration and the anger and being scared. But you had to make that determination of where to break sync.

HULLFISH: You were mentioning the train and how the train sounds got louder and louder and I remember a cut which I loved which was: you’re hearing Saroo and his crying and screaming is in lip-sync where he’s screaming “help me, get me out of here, let me out of this train,” and then there’s moments where he’s talking and screaming but there’s not sound of him talking and screaming. It’s that frustration and the anger and being scared. But you had to make that determination of where to break sync.

DE FRANCESCHI: Exactly. You’re inside his head so that the scream right at the end, we don’t hear it, we hear a horn, Garth put a horn in there that starts about ninety seconds before it comes fully so there’s a really, really loud horn that starts to take over and then he screams and you don’t hear the scream: the outside, mean world has taken over. We then cut out to a wide shot of the train going along the mountain and the music starts. This is the first time we hear the score in the movie (except for the title sequence at the beginning) almost fifteen minutes into it. So that whole combination: the horn, the train, the scream that you can’t hear and the music starting was a gift for the senses. It came with a tremendous amount of work on the sound when we were cutting.

HULLFISH: I definitely noticed and I loved it so, mission accomplished.

DE FRANCESCHI: I love that you love it. I love it when a peer notices those things.

HULLFISH: Chills ran down my spine when Saroo goes into the kitchen to get the beer during the party and sees the Indian pastries – jalebis? Tell me a little bit about that, because that’s a critical moment in the movie when he kind of remembers his old life.

DE FRANCESCHI: That is a critical moment indeed. When Saroo first arrives in Tasmania, he takes in this new alien world: new parents, new house, television, fridge, new sounds. Quiet and peace, you know? Then, very quickly we cut to 20 years later. He’s grown up. He’s not Indian. He’s a good Aussie boy; plays cricket, good to mom and dad. He goes to Uni in Melbourne and he discovers that there are many Indian people around and he is not the only one. He gets interested in a girl. He’s a flirter. There were a few scenes edited out that were showing a little bit more of his real life and job and things like that. Then we get to this Indian party where the food is Indian and there is a lot of joy and happiness. Life is good. These things are working up to the exact moment in the kitchen where he goes to get a drink in the fridge and suddenly he sees that sweet that he couldn’t afford when he was a child, which was the last thing he heard his brother say, “I’m going to bring you a thousand jalebis.” Suddenly, a whole world comes back. You could make an analogy to Proust’s memory of the madeleine in In Search Of Lost Time. For Saroo, to taste the sweet for the first time triggers his longing. We planted the seed a while ago and it suddenly erupts into full maturity. Cutting-wise, it was a simple scene to cut. The previous scene, the dinner party was fun, with jump-cuts and bits and pieces of dialog interlacing. Once in the kitchen, there was some debate on “do we keep him saying ‘I’m lost’ or not?” It’s in the movie, for quite awhile it wasn’t there. Those are the things one discovers at the latest stage when you start screening the movie and showing it to audiences. How much information you want to give.

HULLFISH: That’s a big part of editing, right? Determining what you’re going to have the audience know and when you’re going to tell it to them. Can you think of any specific points where you felt like this is the perfect time to reveal this information?

DE FRANCESCHI: Not specific points. The intention was to maintain the curve of his growing anxiety; his growing need to keep the search going. He knew his birth mother was looking for him. Real-life Saroo Brierley knew his mother was looking for him and his birth-mother knew he was looking for her. She said, “I knew he was alive.” He said, “I knew she was still looking for me I could see her in my dreams.” There was a process from this man being aware that his family was looking for him, and this was upsetting him to the point where he was losing touch with real life. He lost his job. He decided to lose his girlfriend and to dedicate himself totally and completely to the search.

DE FRANCESCHI: Not specific points. The intention was to maintain the curve of his growing anxiety; his growing need to keep the search going. He knew his birth mother was looking for him. Real-life Saroo Brierley knew his mother was looking for him and his birth-mother knew he was looking for her. She said, “I knew he was alive.” He said, “I knew she was still looking for me I could see her in my dreams.” There was a process from this man being aware that his family was looking for him, and this was upsetting him to the point where he was losing touch with real life. He lost his job. He decided to lose his girlfriend and to dedicate himself totally and completely to the search.

HULLFISH: There’s this idea in editing, I’m sure you’re aware – of keeping someone “alive.” If you’re doing multiple storylines, you try to come back to a specific story line so that you don’t feel like “oh it’s been too long since we talked about storyline A and we’ve been in storyline B too long.” There’s a very long time period where we don’t reference Saroo’s brother and then all of a sudden we go back and see him coming back to the train platform and realizing Saroo is gone.

DE FRANCESCHI: That’s such an interesting question. I like how much attention you paid to the movie, it would be nice to meet you over a glass of wine. That moment was scripted as such. That is the very first question I asked myself when reading the script! From memory, it happened around page 60. Through the first reading I kept wondering “Where is the brother? How come we haven’t seen the brother at the station? How come we haven’t had a scene with him discovering that he has lost his little brother and why didn’t we do that straight away?” About five pages later, the scene came in, almost on cue. So we kept it like that in movie. We wanted to save ourselves that little delicacy for later on in the film, which we thought worked, which we thought was appropriate to bring that back after such a long time.

DE FRANCESCHI: That’s such an interesting question. I like how much attention you paid to the movie, it would be nice to meet you over a glass of wine. That moment was scripted as such. That is the very first question I asked myself when reading the script! From memory, it happened around page 60. Through the first reading I kept wondering “Where is the brother? How come we haven’t seen the brother at the station? How come we haven’t had a scene with him discovering that he has lost his little brother and why didn’t we do that straight away?” About five pages later, the scene came in, almost on cue. So we kept it like that in movie. We wanted to save ourselves that little delicacy for later on in the film, which we thought worked, which we thought was appropriate to bring that back after such a long time.

HULLFISH: And I’m not saying it as a criticism by any means, because the other reason – the other great editing point for that – is the idea of editing closely between cause and effect. So finally when you see the brother go back to the platform to look for Saroo, the next scene is him talking about his brother.

DE FRANCESCHI: That’s right. Cause and effect. That’s Garth all over.

HULLFISH: That idea of cause and effect is something that I talked to many editors about. The reason why you want to have those scenes so close together. You might have said “I want to see that scene of going back for Saroo earlier in the movie, but it works perfectly where it is, because then there’s a cause and effect,” you see the brother looking and you hear him his anguish over how his brother must have missed him.

DE FRANCESCHI: Yes, again, Garth’s work. Emotions triggering emotions.

DE FRANCESCHI: Yes, again, Garth’s work. Emotions triggering emotions.

HULLFISH: As we get towards the end of the movie the intercutting starts to become much more involved. Earlier in the movie it was all the child story and then all the adult story. Then it starts to get very interspersed. Is that where you were talking about having 40 bins open?

DE FRANCESCHI: Yes, yes. We put in a bit of muscle there. Inside of interlacing the moments. We had a lot of fun with that I must say. And hard work. The Google search in itself ended up very different from the way it was scripted. There was much more of it, through the whole film. We ended up combining sections into one. It was all beautifully planned and shot but in the end a search is a search and we didn’t need to see it more often that that.

HULLFISH: Was it very hard for the organization of that? Did you see Arrival?

DE FRANCESCHI: Yes. I loved the editing. Beautifully subtle.

HULLFISH: So to me, there’re similarities. In Arrival there’re “memories” of her daughter and it gets chopped up and used in various places in the movie. So how do you organize your bins when there’s so much cutting back to old memories of the other life?

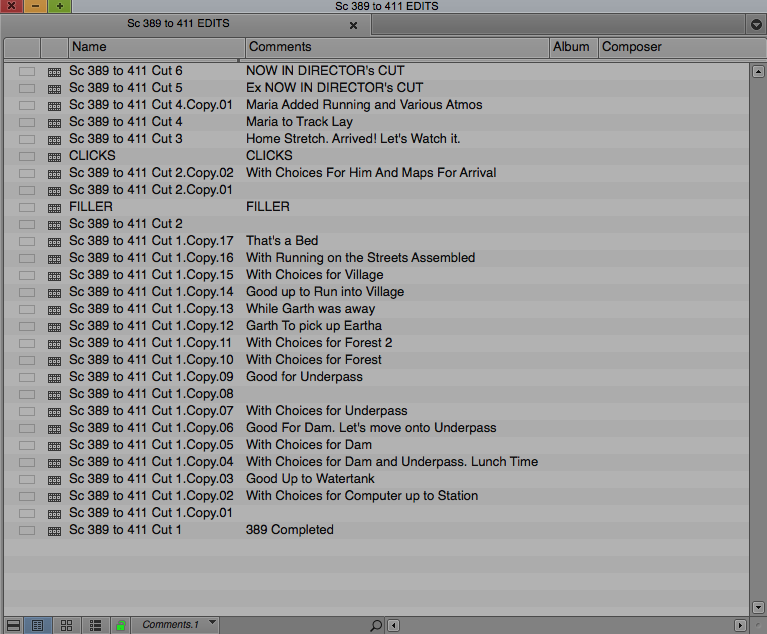

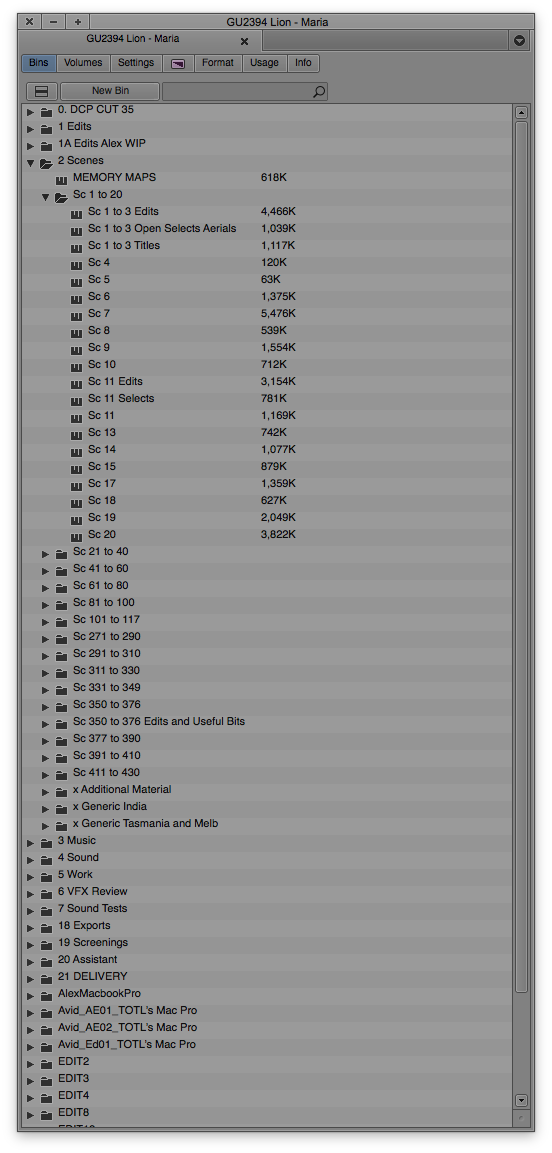

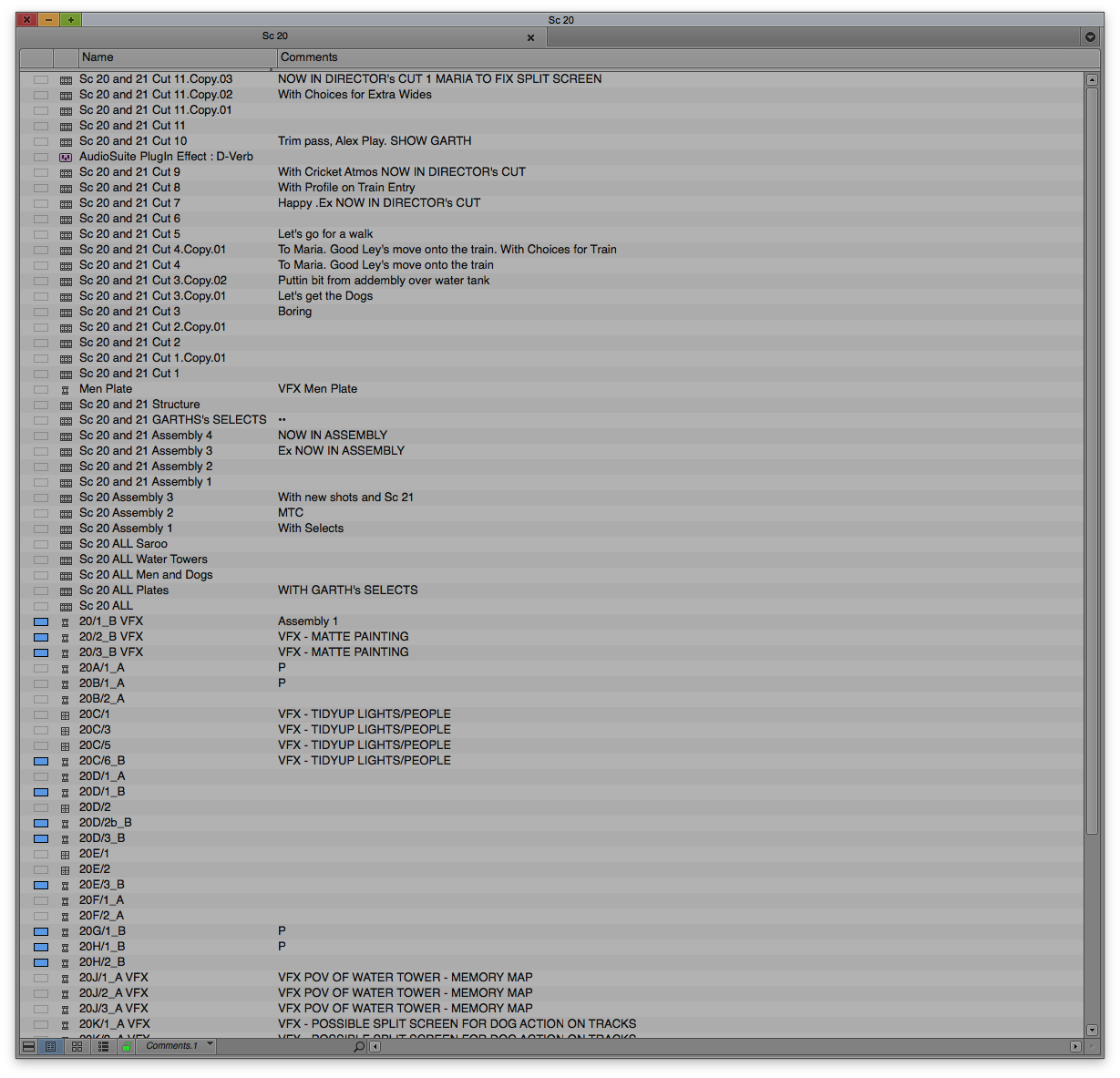

DE FRANCESCHI: That’s a very good question. With a lot of work, I must say. Normally (if there is such a thing as normality in any film) I would cut per scene numbers. You know, you just have a number and you’re guided by the script. In this particular case we started having bins with names as well and then bins within bins within bins or sections so we would create a whole section that might have ten scenes or twenty scenes or thirty scenes. So I would create a folder for that and I would put all the bins into one folder and then start the process of elimination. So you build sequences that have just the bits. It’s not really a structure yet, it’s just bits that you go, “That’s going to be interesting, that’s going to be useful,” so we start grabbing from all these scenes the things that are going to be relevant to that particular point and once we have an idea – once we have a map, we were calling this a ‘map of the area’ then we would start cutting. So what I did, I started using bins in a way that I used to use sequences. I would have a sequence of selects and then a sequence of second selects. So it got a little bit complicated. It needed a lot of attention from the beginning and also we were dealing with subtitles and different languages. Lots of additional material was shot for this purpose, lots of drones, lots of landscapes. We weren’t telling the film what to say, the film was telling us much more what to do and we needed to be ready and to have that material ready.

DE FRANCESCHI: That’s a very good question. With a lot of work, I must say. Normally (if there is such a thing as normality in any film) I would cut per scene numbers. You know, you just have a number and you’re guided by the script. In this particular case we started having bins with names as well and then bins within bins within bins or sections so we would create a whole section that might have ten scenes or twenty scenes or thirty scenes. So I would create a folder for that and I would put all the bins into one folder and then start the process of elimination. So you build sequences that have just the bits. It’s not really a structure yet, it’s just bits that you go, “That’s going to be interesting, that’s going to be useful,” so we start grabbing from all these scenes the things that are going to be relevant to that particular point and once we have an idea – once we have a map, we were calling this a ‘map of the area’ then we would start cutting. So what I did, I started using bins in a way that I used to use sequences. I would have a sequence of selects and then a sequence of second selects. So it got a little bit complicated. It needed a lot of attention from the beginning and also we were dealing with subtitles and different languages. Lots of additional material was shot for this purpose, lots of drones, lots of landscapes. We weren’t telling the film what to say, the film was telling us much more what to do and we needed to be ready and to have that material ready.

HULLFISH: Joe Walker said he did pretty much the same thing where he just had bins of descriptive material, so when he knew “I need to go back for flashback,” it wasn’t necessarily a scene number, it was “Now I need a shot of the daughter.” So was a lot of that organization done by your assistant?

HULLFISH: Joe Walker said he did pretty much the same thing where he just had bins of descriptive material, so when he knew “I need to go back for flashback,” it wasn’t necessarily a scene number, it was “Now I need a shot of the daughter.” So was a lot of that organization done by your assistant?

DE FRANCESCHI: My assistant was also my VFX editor so she worked hard. If you start organizing yourself from day one in a way that is going to make sense later on then you’re in good shape. If you come into the edit at a later stage and things haven’t been organized from the beginning then you have trouble, so from day one we had a very clear path of how we wanted to organize our bins. I had a beautiful, great assistant. Maria Papoutsis, half-Russian, half-Greek and half-Australian, if that makes any sense, and she has all the qualities from those cultures and none of the faults. She’s going to put me out of my job one day soon. First she had to find a way to subtitle all of the Indian rushes, that was no small task. Then she had to organize the bins in a way that made sense. Then she prep’d in all the VFX. I’ve never seen anyone work so hard. But we collaborate a lot. Through the years, I’ve taken a lot of pride in seeing my assistants become editors, I think passing on knowledge is part of my duty. I just don’t walk into the room and expect things to happen. I communicate with my assistants at length and give them small scenes to cut as well, so they stay interested. They give so much in return! Assistants are integral part of the job. They are not just someone two doors down that gets called when something is needed. For Lion we were lucky to have two adjacent cutting rooms so we could talk to each other without having to pick up the phone or walk down the corridor. There was a nice family feeling. And I must give Maria credit as well for the help she provided with track-laying sound.

DE FRANCESCHI: My assistant was also my VFX editor so she worked hard. If you start organizing yourself from day one in a way that is going to make sense later on then you’re in good shape. If you come into the edit at a later stage and things haven’t been organized from the beginning then you have trouble, so from day one we had a very clear path of how we wanted to organize our bins. I had a beautiful, great assistant. Maria Papoutsis, half-Russian, half-Greek and half-Australian, if that makes any sense, and she has all the qualities from those cultures and none of the faults. She’s going to put me out of my job one day soon. First she had to find a way to subtitle all of the Indian rushes, that was no small task. Then she had to organize the bins in a way that made sense. Then she prep’d in all the VFX. I’ve never seen anyone work so hard. But we collaborate a lot. Through the years, I’ve taken a lot of pride in seeing my assistants become editors, I think passing on knowledge is part of my duty. I just don’t walk into the room and expect things to happen. I communicate with my assistants at length and give them small scenes to cut as well, so they stay interested. They give so much in return! Assistants are integral part of the job. They are not just someone two doors down that gets called when something is needed. For Lion we were lucky to have two adjacent cutting rooms so we could talk to each other without having to pick up the phone or walk down the corridor. There was a nice family feeling. And I must give Maria credit as well for the help she provided with track-laying sound.

HULLFISH: The other sound place that I noticed that I loved was just before Saroo meets his mother he starts walking around a corner and he sees some old women, talk to me about the sound design as that point.

DE FRANCESCHI: One of my favorite moments. At this point, we hear the world from Saroo’s perspective, and he’s hearing it with his childhood senses in full alert. Garth wanted to communicate the feeling that something important is about to happen, something that is not part of every day life. Saroo is so acutely focused that all he’s hearing is the silence of what’s around, the space between the words some would say, everything gets deafened and his whole being, his true spirit is focused. Garth wanted the audience to think, “I’m in another world. Something’s going to happen. Something’s magic.” It took some experimenting to get the scene into shape, not just for sound but for mirroring the mother/son approach.

HULLFISH: So you’re cutting in Avid and we talked a little bit about organizing and bins. Inside of a bin, are you a frame view person? Do you like things laid out in specific ways inside the bin? And how do you watch dailies?

DE FRANCESCHI: I used to watch dailies when we would ingest them into the Avid – you know when we shot on film, transferred to tape, and digitized? It was a perfect moment to sit down as the rushes went down in real time and watch them. Now we have files. The ingest happens much quicker so you don’t really get a chance to sit down and watch rushes that way. So I changed my way of working. First of all, when I organize my bins, I’m always in Text view. I never use Frames, I find those distracting. I have one bin per scene: so the scene would be say, Scene 23, so every clip will be named with 23 to start with, then the set-up letter and then the take number. Pretty standard. That’s all I use, I like simplicity. Most of the time multicamera, so I use the group clip. I get rid of the single clip. I like my life in the Avid as simple, clean and easy as possible. Cutting is chaotic enough without having to deal with messy bins. I start from the bottom. At the bottom I will have take one, take two, take three, take four and then on top of all that I have one sequence with all the rushes in it. That is– I’m going back to nonlinear stage at this point in time. The way we used to do it when cutting on film. I have all the rushes from that scene in one single sequence, separated with black for different setups and both cameras also together in there. I watch that, then I duplicate and make a sequence that is first selects and then I have my assembly. This is while the shoot goes on, so I still don’t know what we’re doing, what we’re cutting, I’m just assembling the scene, I’m not trying to cut. I don’t pretend that at this point in time I know what the thing is going to do, what lines of dialogue we’re going to lose, what others are going to be added. It’s just, “lets assemble the scene, let’s use all the elements that have been shot, all the angles, all the scripted lines and move on because the next set of rushes has arrived.” We call that an assembly and I’m quite loose in my assemblies. Everything is there. I don’t try to fine-cut because I know that the harder I try, the more I’m going to mess it up at the end, so keep it simple. I put that in a different roll, my assembly roll. We carry on. Once I start cutting with the director I go back—every time I come into a scene I will extract that scene from the assembly, I will make a sub and I will put that sub in the scene and then I will duplicate that and say “whatever I think is starting to work or bits that are starting to work, I save them, I make myself a little note.” Very quickly I realize, “okay this scene works up to this point, save that.” Because you never know what’s going to happen. Once I have a scene that I’m happy with, I put it in the cut and I save it in the edit. So I might end up with very complicated bins. For instance, I might have twenty, thirty edits, I keep them all because six months down the line I know I’m going to come back at some stage and some old ideas might come in useful again.

DE FRANCESCHI: I used to watch dailies when we would ingest them into the Avid – you know when we shot on film, transferred to tape, and digitized? It was a perfect moment to sit down as the rushes went down in real time and watch them. Now we have files. The ingest happens much quicker so you don’t really get a chance to sit down and watch rushes that way. So I changed my way of working. First of all, when I organize my bins, I’m always in Text view. I never use Frames, I find those distracting. I have one bin per scene: so the scene would be say, Scene 23, so every clip will be named with 23 to start with, then the set-up letter and then the take number. Pretty standard. That’s all I use, I like simplicity. Most of the time multicamera, so I use the group clip. I get rid of the single clip. I like my life in the Avid as simple, clean and easy as possible. Cutting is chaotic enough without having to deal with messy bins. I start from the bottom. At the bottom I will have take one, take two, take three, take four and then on top of all that I have one sequence with all the rushes in it. That is– I’m going back to nonlinear stage at this point in time. The way we used to do it when cutting on film. I have all the rushes from that scene in one single sequence, separated with black for different setups and both cameras also together in there. I watch that, then I duplicate and make a sequence that is first selects and then I have my assembly. This is while the shoot goes on, so I still don’t know what we’re doing, what we’re cutting, I’m just assembling the scene, I’m not trying to cut. I don’t pretend that at this point in time I know what the thing is going to do, what lines of dialogue we’re going to lose, what others are going to be added. It’s just, “lets assemble the scene, let’s use all the elements that have been shot, all the angles, all the scripted lines and move on because the next set of rushes has arrived.” We call that an assembly and I’m quite loose in my assemblies. Everything is there. I don’t try to fine-cut because I know that the harder I try, the more I’m going to mess it up at the end, so keep it simple. I put that in a different roll, my assembly roll. We carry on. Once I start cutting with the director I go back—every time I come into a scene I will extract that scene from the assembly, I will make a sub and I will put that sub in the scene and then I will duplicate that and say “whatever I think is starting to work or bits that are starting to work, I save them, I make myself a little note.” Very quickly I realize, “okay this scene works up to this point, save that.” Because you never know what’s going to happen. Once I have a scene that I’m happy with, I put it in the cut and I save it in the edit. So I might end up with very complicated bins. For instance, I might have twenty, thirty edits, I keep them all because six months down the line I know I’m going to come back at some stage and some old ideas might come in useful again.

I never sort, so I’m starting at the bottom of the bin, I have my day one rushes and from then going up, up, up until my last sequence that I’m using, it’s at the top of the bin. It works for me. I don’t need to go into frame mode because I can, at any time, take my whole sequence with all the rushes and very quickly go through the things and match frame and get the real clip and edit with that. I also use locators a lot, to a great extent. I have a system for that. I have my locators with my notes and when I sit with the director, we talk as we’re watching rushes. He says, “oh that’s nice,” or “that didn’t work for me” or “very nice emotionally there” or “this would work with that.” I write all that down into a locator, whatever the director says goes into a locator. That is invaluable because at some stage, three months down the line we might come back to the same scene again and I can guarantee you ninety-nine percent of the time the director’s going to choose the same beats and say the same thing that he said originally. That spontaneous moment, that moment of going “that’s the beat I’m looking for,” it’s going to help us.

I never sort, so I’m starting at the bottom of the bin, I have my day one rushes and from then going up, up, up until my last sequence that I’m using, it’s at the top of the bin. It works for me. I don’t need to go into frame mode because I can, at any time, take my whole sequence with all the rushes and very quickly go through the things and match frame and get the real clip and edit with that. I also use locators a lot, to a great extent. I have a system for that. I have my locators with my notes and when I sit with the director, we talk as we’re watching rushes. He says, “oh that’s nice,” or “that didn’t work for me” or “very nice emotionally there” or “this would work with that.” I write all that down into a locator, whatever the director says goes into a locator. That is invaluable because at some stage, three months down the line we might come back to the same scene again and I can guarantee you ninety-nine percent of the time the director’s going to choose the same beats and say the same thing that he said originally. That spontaneous moment, that moment of going “that’s the beat I’m looking for,” it’s going to help us.

I learned this from Jane Campion many years ago when I started working with her and I remember saying to her, “How do you like your assemblies?” She said, “make it long, make it boring, don’t worry about it. I know you’re very clever, I know you can cut, but assemblies are just a tool. So let’s have an assembly that is long.” That was great advice. And then when we started working together, you know, we were going through rushes and she would find a bit in those rushes. Just a bit, just something that caught her eye and she would say, “That bit. Get that bit and then let’s build a scene around it.” She wouldn’t say, “This is what’s scripted. This is what they should be saying and how they should be moving.” She would say, “I’m getting a real feeling out of this moment here. How can we make that part the key moment of the scene, forget the script, just make that work.” It drives you mad as an editor because you have no map, no plan. It’s just a complete emotional journey that is beautiful because one gets the sense that it is very pure and true. Garth works in the same way, he is constantly looking for “the truth” in a performance.

I learned this from Jane Campion many years ago when I started working with her and I remember saying to her, “How do you like your assemblies?” She said, “make it long, make it boring, don’t worry about it. I know you’re very clever, I know you can cut, but assemblies are just a tool. So let’s have an assembly that is long.” That was great advice. And then when we started working together, you know, we were going through rushes and she would find a bit in those rushes. Just a bit, just something that caught her eye and she would say, “That bit. Get that bit and then let’s build a scene around it.” She wouldn’t say, “This is what’s scripted. This is what they should be saying and how they should be moving.” She would say, “I’m getting a real feeling out of this moment here. How can we make that part the key moment of the scene, forget the script, just make that work.” It drives you mad as an editor because you have no map, no plan. It’s just a complete emotional journey that is beautiful because one gets the sense that it is very pure and true. Garth works in the same way, he is constantly looking for “the truth” in a performance.

HULLFISH: That was fantastic. That was beautiful, I love that so much. That gives me your approach to a scene. So many people have talked about that idea of selects reels that you continuously tighten and tighten. It gives you that chance to go back almost like a bread crumb trail with Hansel and Gretel where you say, “Oh, I can get back to that place, even though I’ve cut something out maybe.” You mentioned editing with Jane Campion and you also have done a lot of stuff with John Curran. Tell me a little bit about collaboration and how it changes between directors.

DE FRANCESCHI: We all understand that we are good at what we do: the technicalities are sorted out: you know Avid inside-out, you are fast, you can deal with music, you can deal with dialog, you can replace the pop on the “t” of the word “can’t” in the blink of an eye, you have a sense of organization, all those things that make an editor an editor. All that is a given. And then you have your personal taste, a particular sense for pace, culture, sensibilities, those things that cannot be taught and come with life’s experiences. Now that said, the first thing an editor must win is the director’s trust. When the director says, “Who are you? Who are you that is going to deal with my movie? What are you going to do with my baby?” And so my first job is to convince the director that I’m going to help them make the movie they want to make. That I’m going to be the extension of their thoughts, the hands of their brain. And when things don’t work out, I will be able to suggest solutions, to find a path. In the end, I’m the guy who sits between the director and the film. I need to be the friend, the confident, the husband, the cook, the cleaner and the wife. I try to put myself in the head of the director. I need to earn their trust first of all. I need to make sure they are going to be satisfied that it’s not my movie that we’re making; that it’s their movie. Once trust is earned, life is a breeze. It takes time to get to those relationships of trust. You have to deal with the frustrations because you’re the guy in between. Directors want it to happen quickly. They want it to happen now. They’ve got it in their head. It’s working in their head. They want it to be working already on the screen and the editor says, “Well hang on. You just spoke about it and because you have spoken about it doesn’t mean it’s done. Now we need to work it out. So go ahead and take a little walk and come back and see how we can put that together.” But, what a director has to feel from an editor – and you probably would agree with me on this – is that they need your love. They need you to love the movie. They need you to love them and that love has to be genuine and sincere. If you don’t love the movie, if you don’t love the director, it’s going to show. It’s not going to work. The director needs to have the feeling that not only are you going to listen to what they say, you’re going to try to make the movie that they are making. But when it’s not working, you’re going to find a way to get to that spot in ways that they haven’t thought about. And that, I think, is the most important bit of my job.

DE FRANCESCHI: We all understand that we are good at what we do: the technicalities are sorted out: you know Avid inside-out, you are fast, you can deal with music, you can deal with dialog, you can replace the pop on the “t” of the word “can’t” in the blink of an eye, you have a sense of organization, all those things that make an editor an editor. All that is a given. And then you have your personal taste, a particular sense for pace, culture, sensibilities, those things that cannot be taught and come with life’s experiences. Now that said, the first thing an editor must win is the director’s trust. When the director says, “Who are you? Who are you that is going to deal with my movie? What are you going to do with my baby?” And so my first job is to convince the director that I’m going to help them make the movie they want to make. That I’m going to be the extension of their thoughts, the hands of their brain. And when things don’t work out, I will be able to suggest solutions, to find a path. In the end, I’m the guy who sits between the director and the film. I need to be the friend, the confident, the husband, the cook, the cleaner and the wife. I try to put myself in the head of the director. I need to earn their trust first of all. I need to make sure they are going to be satisfied that it’s not my movie that we’re making; that it’s their movie. Once trust is earned, life is a breeze. It takes time to get to those relationships of trust. You have to deal with the frustrations because you’re the guy in between. Directors want it to happen quickly. They want it to happen now. They’ve got it in their head. It’s working in their head. They want it to be working already on the screen and the editor says, “Well hang on. You just spoke about it and because you have spoken about it doesn’t mean it’s done. Now we need to work it out. So go ahead and take a little walk and come back and see how we can put that together.” But, what a director has to feel from an editor – and you probably would agree with me on this – is that they need your love. They need you to love the movie. They need you to love them and that love has to be genuine and sincere. If you don’t love the movie, if you don’t love the director, it’s going to show. It’s not going to work. The director needs to have the feeling that not only are you going to listen to what they say, you’re going to try to make the movie that they are making. But when it’s not working, you’re going to find a way to get to that spot in ways that they haven’t thought about. And that, I think, is the most important bit of my job.

I’ve worked with John Curran for twenty-six years or thereabouts. Fifteen years with Jane Campion. I’m editing Garth Davis second movie as we speak. I remember my first movie with John Curran. It was the first movie for both of us. I was editing commercials at the time, very successfully. Had cut some shorts. Before that, I’d been a sound editor and an assembly editor in features in France and England. Old school path. So John Curran lands this movie and we get very excited. Great book, great script: Praise. The NY Times put it among the best 5 films of the year it was released. I’ve been cutting John’s commercial work and short films for a few years now, we have become friends. Unfortunately he was in quite a bit of pain because he had a back problem. So during the edit he laid on a massage table in the cutting room, unable to move. He was angry. He was in pain. It was his first movie. Imagine. I couldn’t get him out of the room for breaths, so it became difficult. A time came where we started arguing, “Oh, I’m a great editor! I know what I’m doing. Don’t tell me what to do!” And he’d say, “I’m going to tell you what to do and…” …you know how it goes. But, it got to the point that it became quite difficult and ugly. We were having a bad time and one night towards the end of the edit I went back home and I was yelling at my son who was ten at the time, so it wasn’t a good thing. I was passing on anger and I wasn’t in a good spot and I thought, “This is not working. I have to find a solution. I have to find a way to move forward.” It kept me awake at night and then I thought of a solution. The next day, I went into the room and I never said ‘I’ again, I never said the word ‘I.’ I said ‘you’ from then onwards. I said, “John, why don’t you put that wide in there and why don’t you accept that close up and why don’t you move into this scene?” You have no idea what a change of atmosphere there was in the cutting room by just simply deleting the word ‘I’ from my conversations.

I’ve worked with John Curran for twenty-six years or thereabouts. Fifteen years with Jane Campion. I’m editing Garth Davis second movie as we speak. I remember my first movie with John Curran. It was the first movie for both of us. I was editing commercials at the time, very successfully. Had cut some shorts. Before that, I’d been a sound editor and an assembly editor in features in France and England. Old school path. So John Curran lands this movie and we get very excited. Great book, great script: Praise. The NY Times put it among the best 5 films of the year it was released. I’ve been cutting John’s commercial work and short films for a few years now, we have become friends. Unfortunately he was in quite a bit of pain because he had a back problem. So during the edit he laid on a massage table in the cutting room, unable to move. He was angry. He was in pain. It was his first movie. Imagine. I couldn’t get him out of the room for breaths, so it became difficult. A time came where we started arguing, “Oh, I’m a great editor! I know what I’m doing. Don’t tell me what to do!” And he’d say, “I’m going to tell you what to do and…” …you know how it goes. But, it got to the point that it became quite difficult and ugly. We were having a bad time and one night towards the end of the edit I went back home and I was yelling at my son who was ten at the time, so it wasn’t a good thing. I was passing on anger and I wasn’t in a good spot and I thought, “This is not working. I have to find a solution. I have to find a way to move forward.” It kept me awake at night and then I thought of a solution. The next day, I went into the room and I never said ‘I’ again, I never said the word ‘I.’ I said ‘you’ from then onwards. I said, “John, why don’t you put that wide in there and why don’t you accept that close up and why don’t you move into this scene?” You have no idea what a change of atmosphere there was in the cutting room by just simply deleting the word ‘I’ from my conversations.

HULLFISH: That’s a big thing that I’ve talked to many editors about: the very difficult walk that we have to make between having ego because you can’t give a vision to a director without having some ego and confidence in your skills. But then having no ego because you are the conduit – as you said – between the director and his vision. You have to do both.

DE FRANCESCHI: Correct. It’s such a fine line. I have a tendency for whatever reason to be in the emotional journeys of movies. I seem to be better with emotions than car chases to give you a comparison. As I said I’ve done many commercials, lots of car chases there, great discipline also, to tell a story in 30 seconds, it takes skill. Anyway, the emotions are something that come out of the movie and they settle in the cutting room, so you are living that movie and the director is living that movie and the producer is living that movie. So to walk the line, to constantly walk the line between the emotional state of the director and the emotional journey of the movie and my own emotions, it’s hard work. It’s definitely hard work, but very, very rewarding when it works. Lion is a good example because all those emotional journeys are there on the screen. Garth is such a genuine director. He comes into the cutting room every morning and he’s this whirlwind of positive attitude and desire to work. Whatever shot is on the screen when he walks up he just stops and goes “Look at that shot! Isn’t that a beautiful shot? Stunning! Okay, let’s get to work!” And that was the beginning of the day. To look at that smile, to be immersed with that positive attitude is such a gift.

DE FRANCESCHI: Correct. It’s such a fine line. I have a tendency for whatever reason to be in the emotional journeys of movies. I seem to be better with emotions than car chases to give you a comparison. As I said I’ve done many commercials, lots of car chases there, great discipline also, to tell a story in 30 seconds, it takes skill. Anyway, the emotions are something that come out of the movie and they settle in the cutting room, so you are living that movie and the director is living that movie and the producer is living that movie. So to walk the line, to constantly walk the line between the emotional state of the director and the emotional journey of the movie and my own emotions, it’s hard work. It’s definitely hard work, but very, very rewarding when it works. Lion is a good example because all those emotional journeys are there on the screen. Garth is such a genuine director. He comes into the cutting room every morning and he’s this whirlwind of positive attitude and desire to work. Whatever shot is on the screen when he walks up he just stops and goes “Look at that shot! Isn’t that a beautiful shot? Stunning! Okay, let’s get to work!” And that was the beginning of the day. To look at that smile, to be immersed with that positive attitude is such a gift.

HULLFISH: And now you guys are working on another movie together, correct? Magdalene?

DE FRANCESCHI: We are. He shot Mary Magdalene last year. He finished at the end of December I think, and we put it aside because he was exhausted from dealing with Lion and then Mary Magdalene came straight on the tail of that. Then he was on the awards circuit and I was finishing Top of the Lake 2 with Jane Campion, so we are basically starting to cut that this week.

HULLFISH: That’s very unusual to set footage aside that long.

DE FRANCESCHI: Extremely, I’ve never done it before. We have the same producers that we had on Lion, Emile Sherman and Iain Canning, and I’ve done quite a few shows with them already. They have been very understanding and generous in allowing Garth and myself to work together again. The delay was built into the schedule from the beginning. The movie needed to be shot at that particular time because there was an opportunity to shoot with this particular cast and so they decided it was worth shooting while we had the cast at hand and then putting it aside for a little while. I’m sure there’s going to be some pressure to finish sooner than later. Beautiful story. We have an extraordinary cast and I’ve seen the rushes, I’ve seen the assembly and I’m very excited.

DE FRANCESCHI: Extremely, I’ve never done it before. We have the same producers that we had on Lion, Emile Sherman and Iain Canning, and I’ve done quite a few shows with them already. They have been very understanding and generous in allowing Garth and myself to work together again. The delay was built into the schedule from the beginning. The movie needed to be shot at that particular time because there was an opportunity to shoot with this particular cast and so they decided it was worth shooting while we had the cast at hand and then putting it aside for a little while. I’m sure there’s going to be some pressure to finish sooner than later. Beautiful story. We have an extraordinary cast and I’ve seen the rushes, I’ve seen the assembly and I’m very excited.

HULLFISH: The film I’m working on now was shot a few months ago and they waited until I was off my last film to start work on theirs… it’s very unusual. I’m glad you’re getting to work on both!

DE FRANCESCHI: It sounds like we’re both privileged and that some directors and producers understand our value. It’s nice to be acknowledged, most people have no idea what we do.

HULLFISH: Do you have any comments on either of these scenes?

DE FRANCESCHI Sue and John meet Saroo. I love that little scene at the airport. Crucial moment in little Saroo’s life: he is meeting his new parents, he is entering a new world. And we are introducing our star, Nicole Kidman (although I don’t know if anybody noticed, but we had introduced her earlier, in the Indian orphanage, when Saroo is shown the photo album and given a picture of his future parents, John and Sue Brierley. I thought it was a brilliant introduction!). This was such an exquisite and delicate moment, the awkwardness, but also the joy, none of the characters know what to say, and as it happens, the laugh between John and Sue was actually and off-action moment, one of those little gifts. This scene may also be juxtaposed with the arrival of the next adopted child, Mantosh, and the consequences that derived from it.

DE FRANCESCHI: Saroo and Lucy break-up in the street. Another crucial scene, Saroo’s and Lucy’s break-up. This is another turning point in the film and what we call the beginning of “the isolation period”. Saroo has made the decision to give everything he has to the search of his biological family and for that he is prepared to give up his current, comfortable life. It’s been coming and it just explodes now. It was a difficult scene to cut, shot very quickly in a very noisy environment. We used it cleverly to add some information through adr, another good example of re-writing during the edit. I love the way it ends, with Saroo walking away on the bridge, and then we cut to a mirror-image of his birth-mother walking on another bridge, far away from home.

HULLFISH: Just took my wife to see Lion. I knew she’d love it and she did. So I paid to see the movie twice in one day! An excellent job.

HULLFISH: Just took my wife to see Lion. I knew she’d love it and she did. So I paid to see the movie twice in one day! An excellent job.

One of the edits I meant to ask you about earlier, came to my mind again on second viewing. After Saroo finishes the powerful conversation with his ailing adoptive mom, he goes out to the car and there are a couple of jump cuts in close-up as he reacts to the emotion of that talk and it immediately cuts to his real mom and back… kind of cause and effect… I loved this. Setting up the turmoil in his mind and the conflict of emotions about his mother(s). Care to comment on getting that moment right?

DE FRANCESCHI: Haha! I really, really like you! You know, Lion is doing so well because apparently so many people are seeing it twice! Those edits, yes, a little blink to Cassavetes, one of Garth’s favourite directors. Very easy to fall into the indulgent area with those kind of cuts, but we seemed to manage. We wanted the audience to feel his frustration and that time had gone into another dimension. I’d like to think we did well in that.

HULLFISH: Thanks so much for speaking with me today, I thoroughly enjoyed it.

DE FRANCESHI: So did I. I hope we get a chance to meet someday.

Thanks to Noah Adams at Moviola for transcribing this interview. Also thanks to Maria Papoutsis, Alex’s 1st AE, who reached out to connect me with this fascinating story.

Thanks to Noah Adams at Moviola for transcribing this interview. Also thanks to Maria Papoutsis, Alex’s 1st AE, who reached out to connect me with this fascinating story.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The Art of the Cut interviews have been curated into a book that will be released March 10th and is available for pre-order on Amazon now. The book is not a mere collection of interviews, but a topical virtual roundtable discussion by 50 of the world’s top editors – together they have more than a dozen Oscars and more than 40 nominations, not to mention dozens of Emmys, and over 1,000 years of editing experience. The topics include pacing, storytelling, structure, music, sound effects and collaboration.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now