When you’re discussing editing of a tentpole movie with a lot of VFX, tons of footage and a tight deadline, you can be sure that you’ll be discussing it with a team of editors. In this case, those editors are Mark Helfrich, ACE and Steve Edwards. Helfrich’s filmography extends back to the early 80s as an editor on films like, Predator, Rush Hour, Scary Movie, X-Men: Last Stand and Hercules. Steve Edwards has an extensive career in TV starting as an assistant editor on NYPD Blueand edting series like Sirens, Fresh off the Boat, Dear White People and SMILF. He also has feature experience on films including Rein Over Me, Upside of Anger and Sex Tape.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: Tell me about the schedule for Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle.

HELFRICH: We started principal photography mid-September 2016. I went over to Hawaii the week before shooting began to go over plans, previz and all kinds of pre-production stuff with Jake (Kasdan, the director). We ended up shooting until right before Christmas. Steve joined us in the editing room in November.

EDWARDS: Yeah. I have worked on different projects with Jake for the past several years, so he brought me in as an extra pair of hands to help get to Director’s cut more quickly.

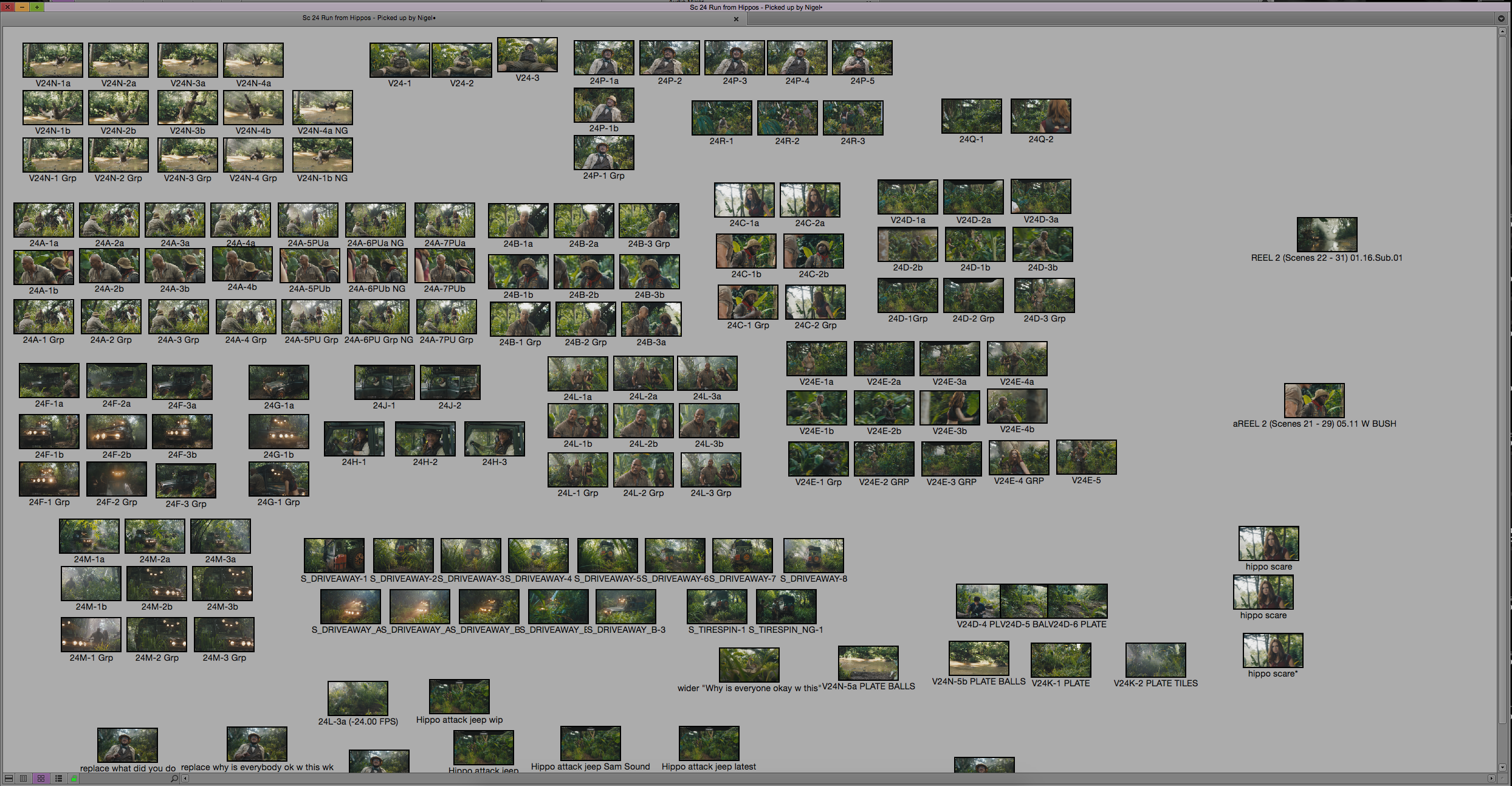

HELFRICH: There was a lot of footage on this. They shot for fifty-nine days and delivered 171 hours and 7 minutes of footage. And that’s just the first unit! — Second unit shot for 27 days. They gave us an additional 44 hours and 30 minutes, for a grand total of 215 hours 37 minutes of film. That’s about nine days worth of footage that we had to cut down to less than two hours.

EDWARDS: Over a 100:1 shooting ratio.

HULLFISH: More and more people that I’m interviewing lately have been part of a team of multiple editors. Do you think that’s a trend because of the speed they’re trying to get things to market or because of the amount of footage or what?

HELFRICH: Often times it’s because there’s so much footage and there’s usually a tight release date. When Steve came on-board, we had a release date in August. Later, it was pushed to Christmas. Originally this was going to be a late summer film and that was a very, very tight schedule.

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about the advantages of working with another editor. Everybody I’ve talked to really loves it that there’s somebody else around to bounce ideas off.

EDWARDS: Yeah, I think it’s really fun and a nice change from what can be a lonely job. Mark is a great guy to work with. He has an enormous amount of passion for what he’s doing and it was really enjoyable to see how he works. I found it fascinating to see his process and was inspired by it. Jake, Mark and I just went through the movie beat by beat, the three of us. It was a tremendous amount of fun.

HELFRICH: We were a tight trio. We spent many, many months and many long hours together. Steve is a really talented editor and a genuinely nice guy. It was exhilarating bouncing ideas back and forth with him. Plus, he’s a gamer, so he brought the gamer-cred. I’d never worked with Jake before, and it’s a pleasure. Talk about being passionate and smart! He’s a director who knows and understands editing – so that’s a real treat.

EDWARDS: Jake also directs on his television series, so he has learned over the years how to move and shoot a tremendous amount very quickly. Most of his shows use improv, so he can really think on his feet and work the material as he’s shooting. There’s a lot of variation, a lot of jokes, which gives us in editorial the chance to really come up with a bunch of alts. Jake is always the last eyes on it and has a knack for finding a way to make it better. He really knows how to work the material. He thinks like a writer. I always learn from working with him, which is what excites me…the chance to improve my craft.

HULLFISH: I definitely want to get back to the idea that Jake thinks like a writer, but first, tell me how you worked together as editors. Every team seems to divide up scenes differently.

HELFRICH: Well, when Steve came aboard I already had several scenes set aside because I hadn’t had time to get to them yet because some of the scenes were huge – especially the action scenes. So there were plenty of scenes backed up for him. And as we were both catching up to the camera, we just divided it up. There were certain scenes I wanted to do and there were certain scenes Steve wanted to do.

EDWARDS: Yeah! I really wanted to do that snake basket scene.

HULLFISH: So once you got through the crush of dailies and you were working on the director’s cut, did you find that you wanted to break things up into sequences instead of scenes?

EDWARDS: Because we were originally on such a tight schedule, the biggest priority was the large visual effects scenes — the animals — we had to get all of that stuff in the pipeline. I remember, Mark, your first big task was the helicopter scene with the rhinos.

EDWARDS: Because we were originally on such a tight schedule, the biggest priority was the large visual effects scenes — the animals — we had to get all of that stuff in the pipeline. I remember, Mark, your first big task was the helicopter scene with the rhinos.

HELFRICH: I spent a long time working on the albino rhino helicopter scene early on. The animals are what took time.

From when the helicopter busts out of the transportation shed to the very end of the sequence where Spencer catches Fridge, that’s about five minutes. I have the stats on that scene: there are 194 shots in those five minutes, and all but two of them are visual effects. In that scene, for every minute of cut film, there were about 166 minutes of material.

One of the first scenes shot was when the avatars get to Jumanji, and that climaxes with Jack Black’s character, Bethany, getting eaten by a hippo. Since that was shot the first week, I was able to cut it and get it in the visual effects pipeline immediately. So the hippo was pretty much done before the film was finished shooting.

HULLFISH: So when the director’s finally in the room with you, how are you working with him collaboratively? You’re each heading off to your separate room and he’s bouncing between you? Did you each take a little chunk of the film or just separate actual scenes?

HELFRICH: We each took chunks, and we didn’t go chronologically.

EDWARDS: While Jake and Mark were focusing on the animals, I was taking Jake’s notes and beginning to recut the beginning of the film — the stuff with the kids. We had ten weeks to get the director’s cut, so we really had to boogie, because the studio wanted to see what they had as quickly as possible.

HELFRICH: Jake would spend a half a day with Steve, then a half a day with me, or sometimes a whole day, and we just kept going.

EDWARDS: Jake likes to screen. He likes to get reactions from people, and I think that comes from his comedy background. So early on, we focused on getting a cut ready for a “friends and family” screening. That told us what we had pretty quickly in terms of jokes, and ins and outs, and what was working and how people felt. A big thing we needed to solve was: how do we get to the Jungle more quickly? I think we were originally at about 24 minutes before we got to the avatars and now we’re down to about 15.

HULLFISH: That idea of how to get to the stars quickly — or any specific important point in a movie — is always a big one. How much did the structure of the film change from the script?

HELFRICH: The film is pretty close to the script. There are very few lifted scenes — maybe two minor scenes, and they were really more like “scene-lets.” There was a little scene where, as kids, Fridge bumped into Martha in the hallway of the school, and that was the whole scene. You can see that shot in the trailer but it’s not in the film. Stuff was cut down, but not much was cut out.

EDWARDS: It is a pretty linear story, so it was not really possible to move things around. It was mostly about the body-switching, so the discussion was always about how much you need to know about the kids to get enough of a sense of them, so that when we did the body-switch people would be able to track their personalities and have fun with that.

HULLFISH: I was wondering whether there was more backstory on the kid that disappears at the beginning of the movie.

HELFRICH: Nope. What you see is what was scripted.

EDWARDS: In an older version of the script, there used to be a more intricate way the game came to the kid. They always found it on the beach, but then it got handed over to a thrift store, right?

HELFRICH: Yeah, in an early draft, the abandoned board game sat forlornly in a thrift store. Year after year everybody just passed it by. Kids were buying video games. And so the board game morphed into a video game and then was picked up. That all went by the wayside before principal photography. None of that was ever shot. It was just an early version of the script.

EDWARDS: After the dad gave the kid the game and he sets it aside, there used to be a bit more time passage with the game sitting on the shelf day after day, but we just decided to speed that up and make it the same day — so Jumanji is a bit more proactive. That was really the most economical cutdown. Mark worked on that sequence with Jake and they were able to capture the essence of the scene in a very quick way.

HULLFISH: You mentioned, Steve, about Jake thinking like a writer, and I really love that idea. Obviously, for an editor, that’s something that feels very comfortable. So tell me a little about how he acts like a writer or why you appreciate that.

EDWARDS: The rhythm of the words is most important to me and that’s something that Jake pays a lot of attention to. He focuses in on the words, the story, the characters all flow out of that. He’s definitely very fluid in his approach to the editing. The first time I worked with him, it really opened my eyes. I had been working on television for a while and show-runners are very attached to their scripts. They like their words. They want their words on screen. But Jake is very fluid about his approach to film. If the script isn’t working, he wants to know: “How can we pull this apart? How can we make it funnier? How can we compact things, move this around?” Editing is REALLY the final rewrite with Jake. It’s one of the reasons I love working with him.

HELFRICH: He’s not precious with his words. He just wants it to work. He wants it to be funny. If it’s a joke, it should get a laugh. We recorded the test screenings and during fine-tuning, if there was a section that was designed to get a laugh, Jake would say, “Bring up the preview.” We’d listen for the audience’s laughter, and if it wasn’t there, we’d figure out why it didn’t get a laugh. And if we couldn’t crack why it wasn’t getting a laugh, then we’d just excise it. We wanted all the beats to work, as everybody does.

HULLFISH: So you guys filmed the audience during the screenings and digitized them?

HULLFISH: So you guys filmed the audience during the screenings and digitized them?

HELFRICH: They were digitized and put into the Avid so we could roll to any part of the film and listen to the audience.

EDWARDS: It is a quick way to see what was working.

HELFRICH: That’s pretty common. Everybody films the preview audience.

HULLFISH: But not everybody brings it into the edit suite. You guys have much more experience than I do, but from my interviews, it seems to be comedies and horror films that are usually the ones that film the audience and then bring that into the edit suite to compare against the cut. I think Ghostbusters did that.

HELFRICH: We actually film the audience so you can see them shifting in their seats if they’re getting bored. Or you can see how many people are getting up and going to the bathroom during a certain scene. You definitely don’t want a scene to be saying, “It’s OK if I get up and go pee right now.”

EDWARDS: You can also see how much your average American movie-goer eats! Also, we always did two simultaneous test screenings — a kids screening and an adult screening.

HELFRICH: We wanted to know which parts played to what audience. It is a family film, so we didn’t want anything that was too risque. We knew we had dick jokes, but we only wanted just the right amount of dick jokes.

HULLFISH: I think you achieved that. I walked out thinking the dick joke balance was perfect.

HELFRICH: Thank you! That was one scene where there was a lot of ad-libbing, especially on Jack Black’s part. When Bethany discovered her penis — he had a field day with that.

HULLFISH: The other one that I would think was heavily improvised is the one where Jack Black is teaching Ruby Roundhouse to flirt.

HELFRICH: Steve cut that.

EDWARDS: That was ALL improv. There was a script, but they only stuck to the general idea of the script. They had broad, general concepts of what they wanted to talk about. Jake would call things out and they would try different variations.

HULLFISH: What is the trick to cutting those improv scenes? Because it’s no longer just following dialogue and using coverage. Now you’re choosing between different lines and many choices, but it can’t just be one long stand-up routine. You’ve still got to tell the story and the character still has to be maintained.

EDWARDS: Yeah, you don’t want it to be too long. You want it to be on point and funny. For me, one of the big things I tried to maintain was the sense the girls’ friendship. I wanted it to feel like they were working together on a problem. Originally, it was one long sequence and that was one of the places we did change the structure a bit and broke it up with the scene of Spencer saying he’d never been kissed. The scene of Spencer talking about kissing was one where Jake wasn’t happy with the first version and they went back and reshot it.

HELFRICH: Jake shot that scene and looked at the cut and decided to shoot a different version in a different location a week or so later. Originally, it was a “walk and talk” and it just turned into a “stand and talk.”

EDWARDS: The scene where she’s actually flirting with the guards is one where Mark and I both took multiple passes. There was a lot of variety there. Mark finally cracked it.

HELFRICH: We had many versions of that scene, trying to get a laugh at the end, and we were failing. So finally I just “stole” a shot from the scene where Bethany was teaching Martha how to flirt, and used that shot of Martha nibbling her lips and put it at the end of the guard-flirting scene. Her lip nibbles got a laugh. We just changed the background of the shot. We took her out of the jungle and put her right in front of the shed.

EDWARDS: Thanks to our insanely talented first assistant editor…

HELFRICH: Yes. Chris Jackson performed miracle temp visual effects. Any idea we had, he was able to execute it so we could pitch it to Jake or screen it for an audience. He’s worked with me for almost 30 years, on and off. He’s just the best ever. As is Laura Yanovich, our other 1st assistant, with whom I go back 20 years. And Sam Sher, our apprentice – we never worked with him before, but he turned out to be a real technical visual wiz. So if we ever wanted to graft a character’s face from one take to their arm movements from another, and place that in a third take with the other characters, and add a bird flying through the frame, or whatever, it was always Steve or Sam who would whip it up and give it to us within minutes.

And everybody contributed to the film’s content. If something wasn’t funny, Jake was open to anybody giving ideas.

EDWARDS: Absolutely, our apprentice, Sam, has ideas of his that are in the movie. He pitched things and they would get incorporated.

HELFRICH: It was a real trusting, open atmosphere in the editing room. We had a whole suite of eight rooms and we basically lived together for the better part of a year. Post production for me was 14 months, 15 months.

HULLFISH: And you guys delivered a locked cut when?

HELFRICH: “Locked” is a term that doesn’t mean what it used to – it’s kind of an antiquated term nowadays. I mean, with VFX, you can’t really lock a film until the last visual effect has been finished.

EDWARDS: We still had 600 or 700 shots to finish when we “locked picture.”

HELFRICH: So we “latch” the picture until we get that final visual effect in, and then we can fine-tune it if we have to, and THEN it’s locked. So it was really locked on the last day we worked… I mean the film was already mixed.

HULLFISH: And when visual effects came in, did those shots need to be trimmed because of the final motion in the visuals?

HELFRICH: They do all the time, especially in action scenes. Rarely does one shot seamlessly match the action of the next, because they’re building each of these shots individually from scratch, with animals or helicopters, or whatever. And the animation sometimes changes from version to version. And quite often there are over a hundred versions of a single shot. So not until you get the final finished animation can you really fine-tune the edit. Plus, there’s the added complexity of different parts of a shot being farmed out to different VFX companies.

EDWARDS: One of the things that fascinated me, not having worked on anything like this before, is that it really was a 24-hour-a-day operation. When we were asleep, there were people in Australia, Mexico City, Montreal… there were visual effects units working all over the world. It was just too big of a special effects movie for one company to handle it and things were bid out on specialties. The company that did the jaguars was the same company that did Jungle Book. There was someone on the planet working all day long every day for over a year on Jumanji.

HULLFISH: Did both of you attend the mix — the sound stage mix?

EDWARDS: Yes. The mix began essentially when we started testing. It actually went back as far as the first studio screening. We did a full temp mix. Julian Slater was our mixer at that point and eventually, Kevin O’Connell joined us. Joel Shryack and our sound team did an amazing job.

HELFRICH: Julian mixed Baby Driver this year and Kevin O’Connell won the Oscar last year for Hacksaw Ridge. They’re a fantastic mixing team and Joel has worked with Jake since his first film, I think.

EDWARDS: With each screening, we had the chance to refine the mix. There were very complicated sound sequences that took a lot of refinement, and over the course of a year, you learn a lot about scenes. We took a long time to get the sound right.

HELFRICH: The film getting delayed from September to December gave our composer, Henry Jackman, a lot more time to live with the film and compose. We had the luxury of time to go over every cue and fine-tune it. Henry’s score is fantastic! It’s big and orchestral and thematic – everything we could want.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about temp score.

HELFRICH: We showed Jake the editor’s cut with a full temp score and for that, we were helped out by a very talented music editor, Chuck Martin Inouye. He used cues from many, many films. Our temp score was not just made up of Henry’s previous scores, Chuck used whatever the scene required. We would go back and forth with Chuck, saying, “Yes, this part works. Can you change the second half of this cue, and make this more driving and add percussion here?” And he always did an amazing job with that.

EDWARDS: We really wanted that nostalgic sound, like a classic Hollywood adventure film. We very purposely didn’t use very many songs. We just wanted it to feel like an old-fashioned film in that regard.

HELFRICH: What did you think of the movie, Steve?

HULLFISH: I liked it. It’s a big, fun popcorn movie. I’m not a big Dwayne Johnson fan but I really liked his performance. The audience I saw it with during the AmazonPrime preview really loved the “smolder” joke. My wife got a kick out of that.

HELFRICH: Ironically, that was one of the bits that Jake was skeptical about: the smolder. Jake saw that for the first time in a cut and thought, “Maybe we should kill that.” Until we showed it to our first screening audience and they thought it was hysterical. The audience really determines, in a comedy, what works.

HULLFISH: Did you discover, after your editor’s cut, that various scenes that felt good when they stood on their own, needed to change because they felt different in the context of the scenes around them?

HELFRICH: Absolutely, especially with this movie. First, they shot the Jumanji jungle scenes in Hawaii, then later they shot the kids’ scenes in Atlanta. We cut together all of the Jumanji stuff with the avatars before we’d seen the personality of the kids. We knew their personalities on paper, but we didn’t know what they looked like or how they spoke or acted. And so once the kids’ scenes were put together I really felt that we needed to rework a lot of the avatar scenes because then we could hone the avatars’ actions to try to match them to the kids’. I discovered that I wanted Ruby Roundhouse to be even more like Martha. Jake knew that, of course. He really knew what he was shooting. Jake had those performances and ideas in his head, but it’s not anything we were privy to until we saw the performances with the kids.

EDWARDS: Yeah, we really had to work from the middle out.

HULLFISH: I totally felt like Dwayne was the high school kid, just in a big body. But I’m sure that you guys probably had performances that he might have played a little bit more like Indiana Jones but you guys had to say, “We need this to play more like that goofy high school kid.

HELFRICH: That’s exactly what I’m talking about. Sometimes something was very funny the way it showed up in dailies, but then we found that he’s not really “playing Spencer” in that particular take. Let’s make it more Spencer-like. It was fun to retroactively re-edit some of those scenes having the benefit of seeing what the performances of the kids were like.

EDWARDS: Yeah. And it was cool because we focused on that for so long. It was a big thrust of the director’s cut, where you’re totally into the “micro” of the moment. Then when we finally sat down in a screening room and watched the whole thing and young Spencer stands up and they’ve beaten Jumanji, it was so gratifying that it worked.

HULLFISH: I loved the final scene where they’re back to being themselves and they walk past the house where the missing kid lives.

HELFRICH: That’s my favorite scene because it’s so touching, and Colin Hanks nailed that scene.

HULLFISH: I’d like to talk about — as two experienced editors — that you realize and expect that editing is a PROCESS. That what you cut the first go-round is going to be gradually improved upon over the course of time.

HELFRICH: That’s completely true. When we put together a scene from the beginning, during dailies, we’re trying to put together the best scene possible – but we know that we’ve got the time later on to hopefully make it even better. That doesn’t always happen. Sometimes you take something out and it actually doesn’t make the scene better, and then you have to go back and rework it, put something back, or take something else out to make it better. And sometimes the first cut is the way it should be.

HULLFISH: Steve, any thoughts on the idea that an editor needs an ego to have something to contribute, but also needs to step back from having an ego to realize that they’re there to support the director’s vision?

EDWARDS: Editors are hired late in the process and you have to respect the fact that, by the time you get to the editing process, the director has been living with the project for a long time. My job is to bring a fresh sense and set of ideas to the project while respecting the vision of the Director. The best projects are a collaboration. On this, my biggest satisfaction is that everybody on the team had their voice heard. We all got to throw ideas into the film.

HELFRICH: We initially put together the scenes to please ourselves, keeping in mind the big picture — that we’re trying tell the best story possible. Then Jake came in and obviously he’s also working to make it better. He doesn’t have an ego. I never once felt that I was cutting it for Jake. We were all cutting it for the audience. Jake‘s so collaborative — I remember during dailies, I saw a shot of Dwayne — as Spencer — just arriving in Jumanji, looking lost — and he touches his head. What went through my mind was: if Spencer is touching his bald head for the first time, he’s going to wonder where his hair went. So I mentioned that to Jake. And in the next day’s dailies there was a shot of Dwayne touching his head and saying, “Where is my hair?” Jake took it even further and had him look at and poke his new muscles. That’s just one example of how collaborative Jake is. He’ll take good ideas from everybody for the bettering of the film.

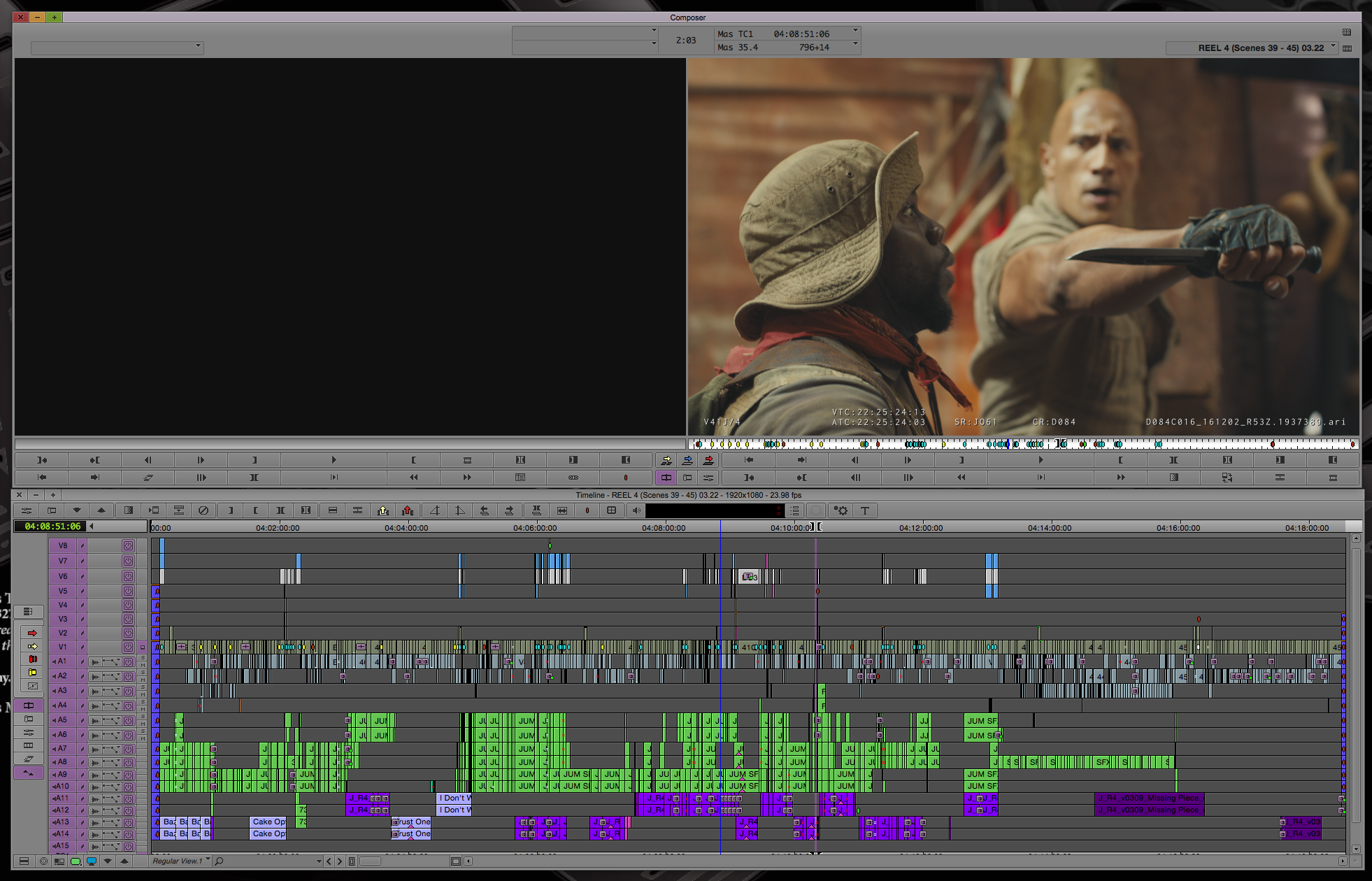

HULLFISH: I’m assuming you guys cut on Avid.

EDWARDS: Yes. Avid on an ISIS.

HULLFISH: I usually ask this earlier in the interviews, but what is your approach when you get dailies? What’s the actual process: from receiving a bin of footage to ending up with the first cut of a scene?

HELFRICH: Depending on the amount of material, you try to watch most of it. Now, on a movie like this, there was so much material that I would only be able to watch one take of every angle, at first. If I watched all the footage that came in every day I would never have time to edit. I start to think, “How am I going to put this together? This is a great angle to be in for this action or this line.” That’s before I start cutting. And often it’s the case where I won’t get to that scene that day because I’m still cutting the previous scene from three days ago, and you get backed up. On a film this large you can’t stay up to camera. Especially with action scenes where they might shoot one action scene over the length of three weeks, so you have to wait until everything is in before you can start putting it together.

HELFRICH: Depending on the amount of material, you try to watch most of it. Now, on a movie like this, there was so much material that I would only be able to watch one take of every angle, at first. If I watched all the footage that came in every day I would never have time to edit. I start to think, “How am I going to put this together? This is a great angle to be in for this action or this line.” That’s before I start cutting. And often it’s the case where I won’t get to that scene that day because I’m still cutting the previous scene from three days ago, and you get backed up. On a film this large you can’t stay up to camera. Especially with action scenes where they might shoot one action scene over the length of three weeks, so you have to wait until everything is in before you can start putting it together.

HULLFISH: Do either one of you guys use select reels, or do you cut strictly from the bins?

EDWARDS: Because there was so much improv on this movie we used Scripter (common Hollywood slang for Avid’s Script Integration or ScriptSync). We had assistants who religiously worked as fast as they could scripting. And the way I work is a line at a time. I watch the dailies. As Mark said, you can’t watch everything during principal photography with this much footage. You get a sense of what the angles are. And I very quickly try to figure out how to start a scene. What’s going to be the first shot and how do you get in? Then I go from there and I feel the performances. I build it line for line and I watch and watch and watch and watch.

HULLFISH: So you actually, instead of editing from a bin, you’re working from what is essentially a lined script inside of Avid.

EDWARDS: Yes. By the time I came on, there was a fair amount that had been scripted. It’s just a great way to quickly see how the scene is covered and be able to watch it line by line.

HELFRICH: I didn’t use ScriptSync when I did my initial cut. Usually, I would use that for all the subsequent cuts because then we could compare the many reads of each line.

EDWARDS: Yeah. It’s a quick way to sense out all the alts when you’re making changes later on.

HULLFISH: Gentlemen, thank you so much for your time. This was very informative and fun.

HELFRICH: Wonderful talking to you.

EDWARDS: Thank you.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now